User login

Agminated Papules on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

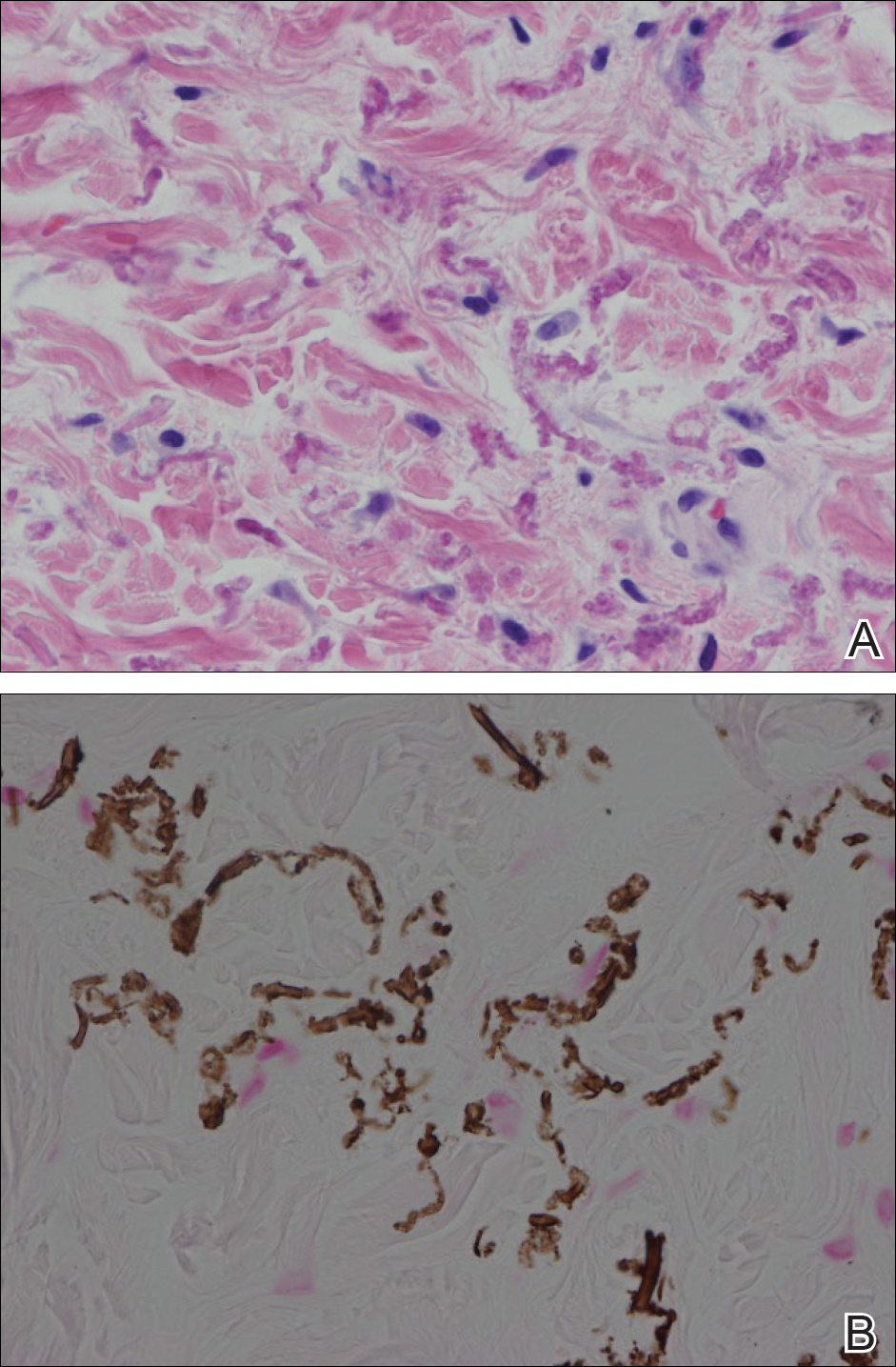

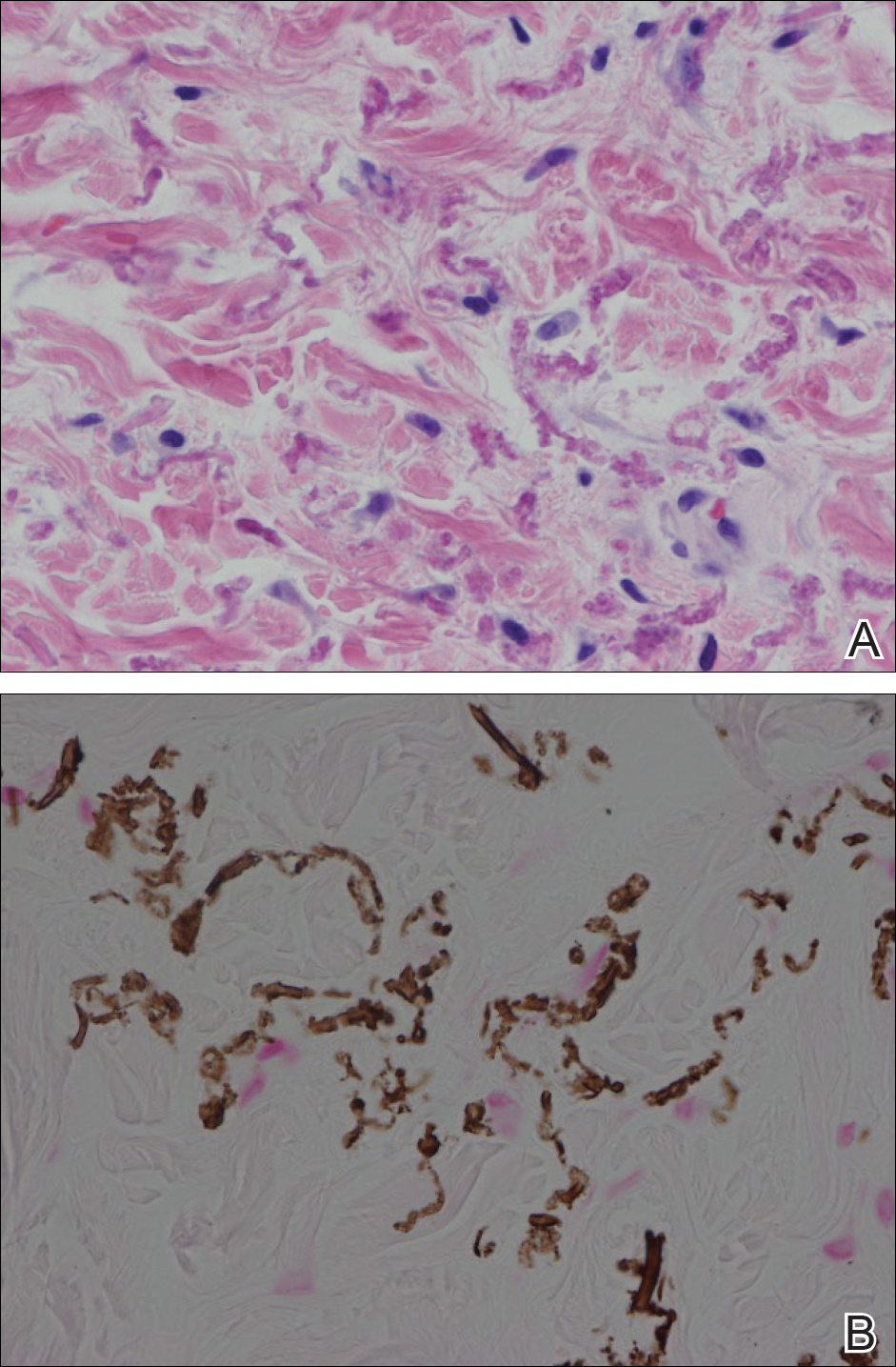

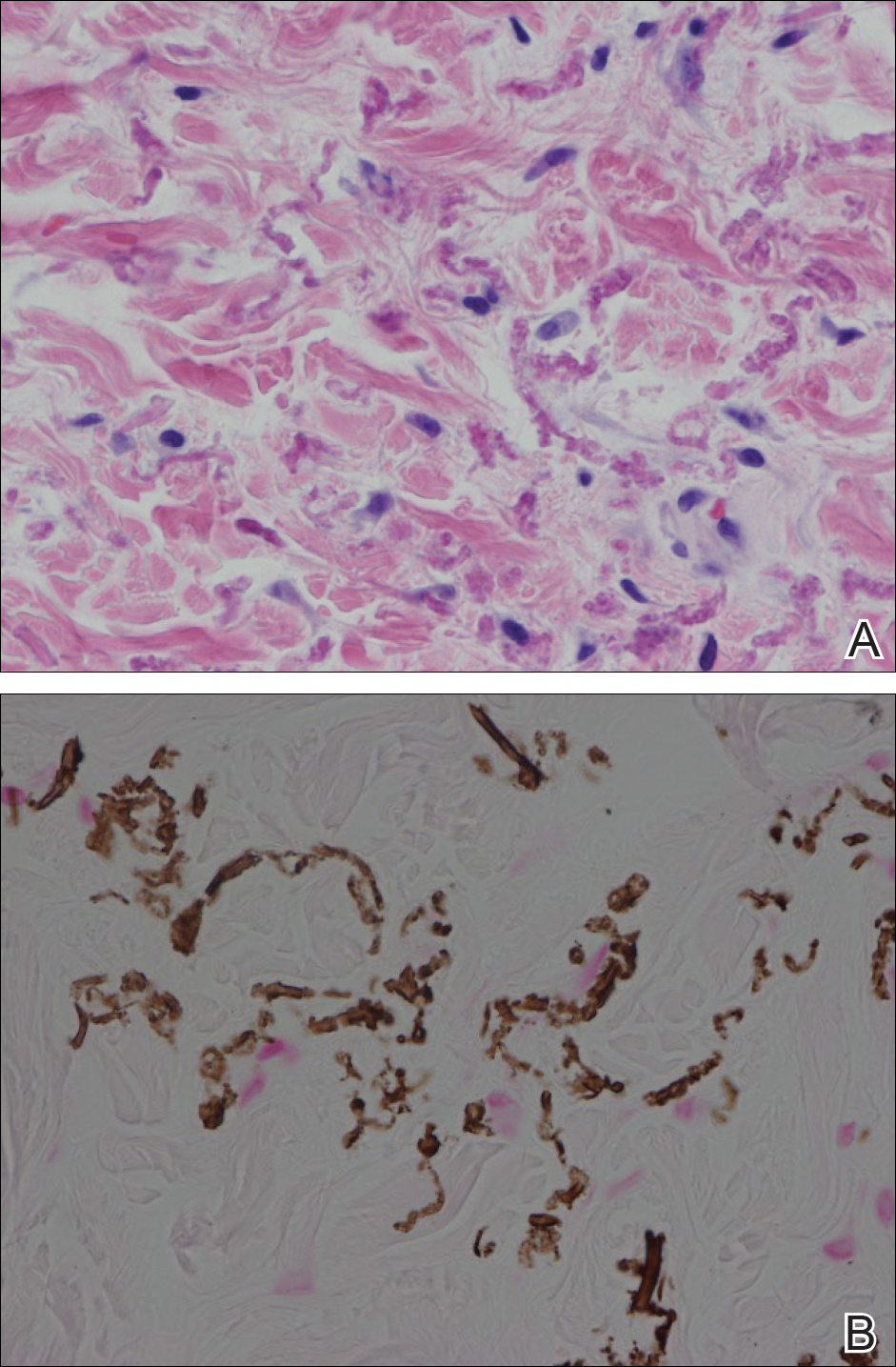

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

A 24-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the neck of 3 months' duration. She noted occasional mild pruritus at the site but no other symptoms or similar lesions elsewhere. At the time of presentation, she was at 17 weeks of gestation without any complications. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, unspecified chest pain with a normal electrocardiogram, and 2 spontaneous abortions. She denied a personal or family history of notable cardiovascular or gastrointestinal tract diseases. Examination of the skin showed indurated 3- to 5-mm papules coalescing into a 3- to 4-cm plaque on the left posterolateral neck.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Pantoprazole

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.