User login

Emergency Ultrasound: Focused Ultrasound for Respiratory Distress: The BLUE Protocol

Acute dyspnea, with or without hypoxia, is a common patient presentation in the ED, and can be the result of a myriad of mainly cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic conditions—many of which are life-threatening. Therefore, it is crucial to determine or narrow the diagnosis promptly and initiate appropriate treatment. Focused ultrasound of the lungs can provide important information that can change a patient’s clinical course within minutes of initial evaluation.

Background

Prior to the 1990s, the lung was considered unsuitable for evaluation by ultrasound given the scatter of the ultrasound beam that is produced by the presence of aerated tissue. Lung pathology, however, produces distinct artifacts and signs on ultrasound that correspond with specific disease patterns.

The Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergencies (BLUE) protocol1 was developed by Daniel Lichtenstein, a French intensivist, and published in 2008. The goal of the examination is to improve the speed and precision of identifying common causes of acute dyspnea. The sensitivity of ultrasound for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pneumothorax were reported as exceeding 88%.2 Strictly speaking, the BLUE protocol includes an evaluation of the deep veins as well to exclude thrombus; however, this article will focus on ultrasound imaging of the lung.

Relevant Findings

A-line Artifact

The A-line seen on lung ultrasound (Figure 1) originates from the pleura and can be seen in a normal lung.

B-line Artifact

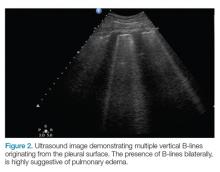

B-lines, also referred to as “lung rockets,” are a comet-tail artifact arising from the pleura (Figure 2).

Lung Profiles

A patient can have one of three predominant lung profiles: A-profile, B-profile, or AB-profile.

A-profile. A-lines appear bilaterally with lung sliding in the anterior surface of lungs, suggestive of COPD, or pulmonary embolism. Exacerbation of congestive heart failure can be ruled out.

B-profile. The appearance of prominent B-lines bilaterally, suggestive of heart failure, essentially rules out COPD, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax.

AB-profile. The appearance of predominant B-lines on one lung and predominant A-lines on the other lung, is consistent with an AB profile. This is usually associated with unilateral pneumonia, especially if seen with other findings such as subpleural consolidation (Figure 3) and air bronchograms (Figure 4).

Lung Point

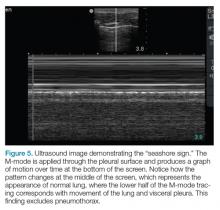

The lung point sign is the only specific finding in the BLUE protocol, and signifies the limits of a pneumothorax by showing the interface between normal lung sliding and the edge of the pneumothorax. Without a specific search for the lung point, it may not be seen in the anterior assessment of lung sliding, although lung sliding will still be abolished.

Imaging Technique

The mid-to-high frequency phased array transducer is used to examine the anterior and posterolateral chest. The original BLUE protocol assesses three zones, but the most relevant information can be obtained from performing the ultrasound in the anterior and posterolateral locations (Figures 6 and 7).

Anterior Pleural Assessment

The first step is to evaluate the pleural line anteriorly (Figure 1) for lung sliding. This is best accomplished by setting the depth to no more than 5 cm so that the focal zone of the ultrasound beam is directed at the pleural line, and it is centered on the screen. If no sliding is present, it is because the visceral and parietal pleura are not apposed to one another. There are many pathological entities that can cause this finding, but one of the more common is pneumothorax.

After evaluating the pleural line, the depth will then need to be switched to 15 cm to evaluate for B-lines. If B-lines are present without lung sliding, pneumonia should be strongly considered. The appearance of B-lines with lung sliding signifies alveolar interstitial fluid, commonly from pulmonary edema.

Posterolateral Assessment

The posterolateral assessment (Figure 7) evaluates for pleural effusion and consolidation. The dome of the diaphragm is the landmark above which abnormal lung and artifacts will be seen.

Summary

Lung ultrasound can help narrow the differential diagnosis for acute dyspnea within the first few minutes of the patient encounter. The BLUE protocol provides an organized approach to this evaluation. Often, the protocol is combined with focused examinations of the heart, inferior vena cava, and/or deep veins to complete the clinical picture. It is important to keep in mind that patients may have two or more pathological conditions (eg, asthma and pneumonia) that can affect the ultrasound findings. For this reason, ultrasound interpretation should always occur in the context of the clinical condition. If it does not exclude important diagnoses, additional investigations such as plain radiography, cross-sectional imaging, or ventilation/perfusion studies should be pursued.

1. Lichtenstein DA. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest. 2015;147(6):1659-1670. doi:10.1378/chest.14-1313.

2. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134(1):117-125. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2800.

Acute dyspnea, with or without hypoxia, is a common patient presentation in the ED, and can be the result of a myriad of mainly cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic conditions—many of which are life-threatening. Therefore, it is crucial to determine or narrow the diagnosis promptly and initiate appropriate treatment. Focused ultrasound of the lungs can provide important information that can change a patient’s clinical course within minutes of initial evaluation.

Background

Prior to the 1990s, the lung was considered unsuitable for evaluation by ultrasound given the scatter of the ultrasound beam that is produced by the presence of aerated tissue. Lung pathology, however, produces distinct artifacts and signs on ultrasound that correspond with specific disease patterns.

The Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergencies (BLUE) protocol1 was developed by Daniel Lichtenstein, a French intensivist, and published in 2008. The goal of the examination is to improve the speed and precision of identifying common causes of acute dyspnea. The sensitivity of ultrasound for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pneumothorax were reported as exceeding 88%.2 Strictly speaking, the BLUE protocol includes an evaluation of the deep veins as well to exclude thrombus; however, this article will focus on ultrasound imaging of the lung.

Relevant Findings

A-line Artifact

The A-line seen on lung ultrasound (Figure 1) originates from the pleura and can be seen in a normal lung.

B-line Artifact

B-lines, also referred to as “lung rockets,” are a comet-tail artifact arising from the pleura (Figure 2).

Lung Profiles

A patient can have one of three predominant lung profiles: A-profile, B-profile, or AB-profile.

A-profile. A-lines appear bilaterally with lung sliding in the anterior surface of lungs, suggestive of COPD, or pulmonary embolism. Exacerbation of congestive heart failure can be ruled out.

B-profile. The appearance of prominent B-lines bilaterally, suggestive of heart failure, essentially rules out COPD, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax.

AB-profile. The appearance of predominant B-lines on one lung and predominant A-lines on the other lung, is consistent with an AB profile. This is usually associated with unilateral pneumonia, especially if seen with other findings such as subpleural consolidation (Figure 3) and air bronchograms (Figure 4).

Lung Point

The lung point sign is the only specific finding in the BLUE protocol, and signifies the limits of a pneumothorax by showing the interface between normal lung sliding and the edge of the pneumothorax. Without a specific search for the lung point, it may not be seen in the anterior assessment of lung sliding, although lung sliding will still be abolished.

Imaging Technique

The mid-to-high frequency phased array transducer is used to examine the anterior and posterolateral chest. The original BLUE protocol assesses three zones, but the most relevant information can be obtained from performing the ultrasound in the anterior and posterolateral locations (Figures 6 and 7).

Anterior Pleural Assessment

The first step is to evaluate the pleural line anteriorly (Figure 1) for lung sliding. This is best accomplished by setting the depth to no more than 5 cm so that the focal zone of the ultrasound beam is directed at the pleural line, and it is centered on the screen. If no sliding is present, it is because the visceral and parietal pleura are not apposed to one another. There are many pathological entities that can cause this finding, but one of the more common is pneumothorax.

After evaluating the pleural line, the depth will then need to be switched to 15 cm to evaluate for B-lines. If B-lines are present without lung sliding, pneumonia should be strongly considered. The appearance of B-lines with lung sliding signifies alveolar interstitial fluid, commonly from pulmonary edema.

Posterolateral Assessment

The posterolateral assessment (Figure 7) evaluates for pleural effusion and consolidation. The dome of the diaphragm is the landmark above which abnormal lung and artifacts will be seen.

Summary

Lung ultrasound can help narrow the differential diagnosis for acute dyspnea within the first few minutes of the patient encounter. The BLUE protocol provides an organized approach to this evaluation. Often, the protocol is combined with focused examinations of the heart, inferior vena cava, and/or deep veins to complete the clinical picture. It is important to keep in mind that patients may have two or more pathological conditions (eg, asthma and pneumonia) that can affect the ultrasound findings. For this reason, ultrasound interpretation should always occur in the context of the clinical condition. If it does not exclude important diagnoses, additional investigations such as plain radiography, cross-sectional imaging, or ventilation/perfusion studies should be pursued.

Acute dyspnea, with or without hypoxia, is a common patient presentation in the ED, and can be the result of a myriad of mainly cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic conditions—many of which are life-threatening. Therefore, it is crucial to determine or narrow the diagnosis promptly and initiate appropriate treatment. Focused ultrasound of the lungs can provide important information that can change a patient’s clinical course within minutes of initial evaluation.

Background

Prior to the 1990s, the lung was considered unsuitable for evaluation by ultrasound given the scatter of the ultrasound beam that is produced by the presence of aerated tissue. Lung pathology, however, produces distinct artifacts and signs on ultrasound that correspond with specific disease patterns.

The Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergencies (BLUE) protocol1 was developed by Daniel Lichtenstein, a French intensivist, and published in 2008. The goal of the examination is to improve the speed and precision of identifying common causes of acute dyspnea. The sensitivity of ultrasound for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pneumothorax were reported as exceeding 88%.2 Strictly speaking, the BLUE protocol includes an evaluation of the deep veins as well to exclude thrombus; however, this article will focus on ultrasound imaging of the lung.

Relevant Findings

A-line Artifact

The A-line seen on lung ultrasound (Figure 1) originates from the pleura and can be seen in a normal lung.

B-line Artifact

B-lines, also referred to as “lung rockets,” are a comet-tail artifact arising from the pleura (Figure 2).

Lung Profiles

A patient can have one of three predominant lung profiles: A-profile, B-profile, or AB-profile.

A-profile. A-lines appear bilaterally with lung sliding in the anterior surface of lungs, suggestive of COPD, or pulmonary embolism. Exacerbation of congestive heart failure can be ruled out.

B-profile. The appearance of prominent B-lines bilaterally, suggestive of heart failure, essentially rules out COPD, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax.

AB-profile. The appearance of predominant B-lines on one lung and predominant A-lines on the other lung, is consistent with an AB profile. This is usually associated with unilateral pneumonia, especially if seen with other findings such as subpleural consolidation (Figure 3) and air bronchograms (Figure 4).

Lung Point

The lung point sign is the only specific finding in the BLUE protocol, and signifies the limits of a pneumothorax by showing the interface between normal lung sliding and the edge of the pneumothorax. Without a specific search for the lung point, it may not be seen in the anterior assessment of lung sliding, although lung sliding will still be abolished.

Imaging Technique

The mid-to-high frequency phased array transducer is used to examine the anterior and posterolateral chest. The original BLUE protocol assesses three zones, but the most relevant information can be obtained from performing the ultrasound in the anterior and posterolateral locations (Figures 6 and 7).

Anterior Pleural Assessment

The first step is to evaluate the pleural line anteriorly (Figure 1) for lung sliding. This is best accomplished by setting the depth to no more than 5 cm so that the focal zone of the ultrasound beam is directed at the pleural line, and it is centered on the screen. If no sliding is present, it is because the visceral and parietal pleura are not apposed to one another. There are many pathological entities that can cause this finding, but one of the more common is pneumothorax.

After evaluating the pleural line, the depth will then need to be switched to 15 cm to evaluate for B-lines. If B-lines are present without lung sliding, pneumonia should be strongly considered. The appearance of B-lines with lung sliding signifies alveolar interstitial fluid, commonly from pulmonary edema.

Posterolateral Assessment

The posterolateral assessment (Figure 7) evaluates for pleural effusion and consolidation. The dome of the diaphragm is the landmark above which abnormal lung and artifacts will be seen.

Summary

Lung ultrasound can help narrow the differential diagnosis for acute dyspnea within the first few minutes of the patient encounter. The BLUE protocol provides an organized approach to this evaluation. Often, the protocol is combined with focused examinations of the heart, inferior vena cava, and/or deep veins to complete the clinical picture. It is important to keep in mind that patients may have two or more pathological conditions (eg, asthma and pneumonia) that can affect the ultrasound findings. For this reason, ultrasound interpretation should always occur in the context of the clinical condition. If it does not exclude important diagnoses, additional investigations such as plain radiography, cross-sectional imaging, or ventilation/perfusion studies should be pursued.

1. Lichtenstein DA. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest. 2015;147(6):1659-1670. doi:10.1378/chest.14-1313.

2. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134(1):117-125. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2800.

1. Lichtenstein DA. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest. 2015;147(6):1659-1670. doi:10.1378/chest.14-1313.

2. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134(1):117-125. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2800.