User login

Pediatric Hospitalist Variation in Care

Reduction of undesirable variation in care has been a major focus of systematic efforts to improve the quality of the healthcare system.13 The emergence of hospitalists, physicians specializing in the care of hospitalized patients, was spurred by a desire to streamline care and reduce variability in hospital management of common diseases.4, 5 Over the past decade, hospitalist systems have become a leading vehicle for care delivery.4, 6, 7 It remains unclear, however, whether implementation of hospitalist systems has lessened undesirable variation in the inpatient management of common diseases.

While systematic reviews have found costs and hospital length of stay to be 10‐15% lower in both pediatric and internal medicine hospitalist systems, few studies have adequately assessed the processes or quality of care in hospitalist systems.8, 9 Two internal medicine studies have found decreased mortality in hospitalist systems, but the mechanism by which hospitalists apparently achieved these gains is unclear.10, 11 Even less is known about care processes or quality in pediatric hospitalist systems. Death is a rare occurrence in pediatric ward settings, and the seven studies conducted to date comparing pediatric hospitalist and traditional systems have been universally underpowered to detect differences in mortality.9, 1218 There is a need to better understand care processes as a first step in understanding and improving quality of care in hospitalist systems.19

The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network was formed to improve the quality of care for hospitalized children through collaborative clinical research. In this study, we sought to study variation in the care of common pediatric conditions among a cohort of pediatric hospitalists. We have previously reported that less variability exists in hospitalists' reported management of inpatient conditions than in the reported management of these same conditions by community‐based pediatricians,20 but we were concerned that substantial undesirable variation (ie, variation in practice due to uncertainty or unsubstantiated local practice traditions, rather than justified variation in care based on different risks of harms or benefits in different patients) may still exist among hospitalists. We therefore conducted a study: 1) to investigate variation in hospitalists' reported use of common inpatient therapies, and 2) to test the hypothesis that greater variation exists in hospitalists' reported use of inpatient therapies of unproven benefit than in those therapies proven to be beneficial.

METHODS

Survey Design and Administration

In 2003, we designed the PRIS Survey to collect data on hospitalists' backgrounds, practices, and training needs, as well as their management of common pediatric conditions. For the current study, we chose a priori to evaluate hospitalists' use of 14 therapies in the management of 4 common conditions: asthma, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and gastro‐esophageal reflux disease (GERD) (Table 1). These four conditions were chosen for study because they were among the top discharge diagnoses (primary and secondary) from the inpatient services at 2 of the authors' institutions (Children's Hospital Boston and Children's Hospital San Diego) during the year before administration of the survey, and because a discrete set of therapeutic agents are commonly used in their management. Respondents were asked to report the frequency with which they used each of the 14 therapies of interest on 5‐point Likert scales (from 1=never to 5=almost always). The survey initially developed was piloted with a small group of hospitalists and pediatricians, and a final version incorporating revisions was subsequently administered to all pediatric hospitalists in the US and Canada identified through any of 3 sources: 1) the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) list of participants; 2) the Society for Hospital Medicine (SHM) pediatric hospital medicine e‐mail listserv; and 3) the list of all attendees of the first national pediatric hospitalist conference sponsored by the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association (APA), SHM, and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP); this meeting was held in San Antonio, Texas, USA in November 2003. Individuals identified through more than 1 of these groups were counted only once. Potential participants were assured that individual responses would be kept confidential, and were e‐mailed an access code to participate in the online survey, using a secure web‐based interface; a paper‐based version was also made available to those who preferred to respond in this manner. Regular reminder notices were sent to all non‐responders. Further details regarding PRIS Survey recruitment and study methods have been published previously.20

| Condition | Therapy | BMJ clinical evidence Treatment effect categorization* | Study classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Asthma | Inhaled albuterol | Beneficial | Proven |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Beneficial | Proven | |

| Inhaled ipratropium in the first 24 hours of hospitalization | Beneficial | Proven | |

| Inhaled ipratropium after the first 24 hours of hospitalization | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Bronchiolitis | Inhaled albuterol | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven |

| Inhaled epinephrine | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Gastroenteritis | Intravenous hydration | Beneficial | Proven |

| Lactobacillus | Not assessed | Unproven | |

| Ondansetron | Not assessed | Unproven | |

| Gastro‐Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) | H2 histamine‐receptor antagonists | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven |

| Thickened feeds | Unknown effectiveness Likely to be beneficial | Unproven Proven | |

| Metoclopramide | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Proton‐pump inhibitors | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

DefinitionsReference Responses and Percent Variation

To measure variation in reported management, we first sought to determine a reference response for each therapy of interest. Since the evidence base for most of the therapies we studied is weak, it was not possible to determine a gold standard response for each therapy. Instead, we sought to measure the degree of divergence from a reference response for each therapy in the following manner. First, to simplify analyses, we collapsed our five‐category Likert scale into three categories (never/rarely, sometimes, and often/almost always). We then defined the reference response for each therapy to be never/rarely or often/almost always, whichever of the 2 was more frequently selected by respondents; sometimes was not used as a reference category, as reporting use of a particular therapy sometimes indicated substantial variability even within an individual's own practice.

Classification of therapies as proven or unproven.

To classify each of the 14 studied therapies as being of proven or unproven, we used the British Medical Journal's publication Clinical Evidence.19 We chose to use Clinical Evidence as an evidence‐based reference because it provides rigorously developed, systematic analyses of therapeutic management options for multiple common pediatric conditions, and organizes recommendations in a straightforward manner. Four of the 14 therapies had been determined on systematic review to be proven beneficial at the time of study design: systemic corticosteroids, inhaled albuterol, and ipratropium (in the first 24 h) in the care of children with asthma; and IV hydration in the care of children with acute gastroenteritis. The remaining 10 therapies were either considered to be of unknown effectiveness or had not been formally evaluated by Clinical Evidence, and were hence considered unproven for this study (Table 1). Of note, the use of thickened feeds in the treatment of children with GERD had been determined to be of unknown effectiveness at the time of study design, but was reclassified as likely to be beneficial during the course of the study.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to report respondents' demographic characteristics and work environments, as well as variation in their reported use of each of the 14 therapies. Variation in hospitalists' use of proven versus unproven therapies was compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, as it was distributed non‐normally. For our primary analysis, the use of thickened feeds in GERD was considered unproven, but a sensitivity analysis was conducted reclassifying it as proven in light of the evolving literature on its use and its consequent reclassification in Clinical Evidence.(SAS Version 9.1, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

213 of the 320 individuals identified through the 3 lists of pediatric hospitalists (67%) responded to the survey. Of these, 198 (93%) identified themselves as hospitalists and were therefore included. As previously reported,20 53% of respondents were male, 55% worked in academic training environments, and 47% had completed advanced training (fellowship) beyond their core pediatric training (residency training); respondents reported completing residency training 11 9 (mean, standard deviation) years prior to the survey, and spending 176 72 days per year in the care of hospitalized patients.

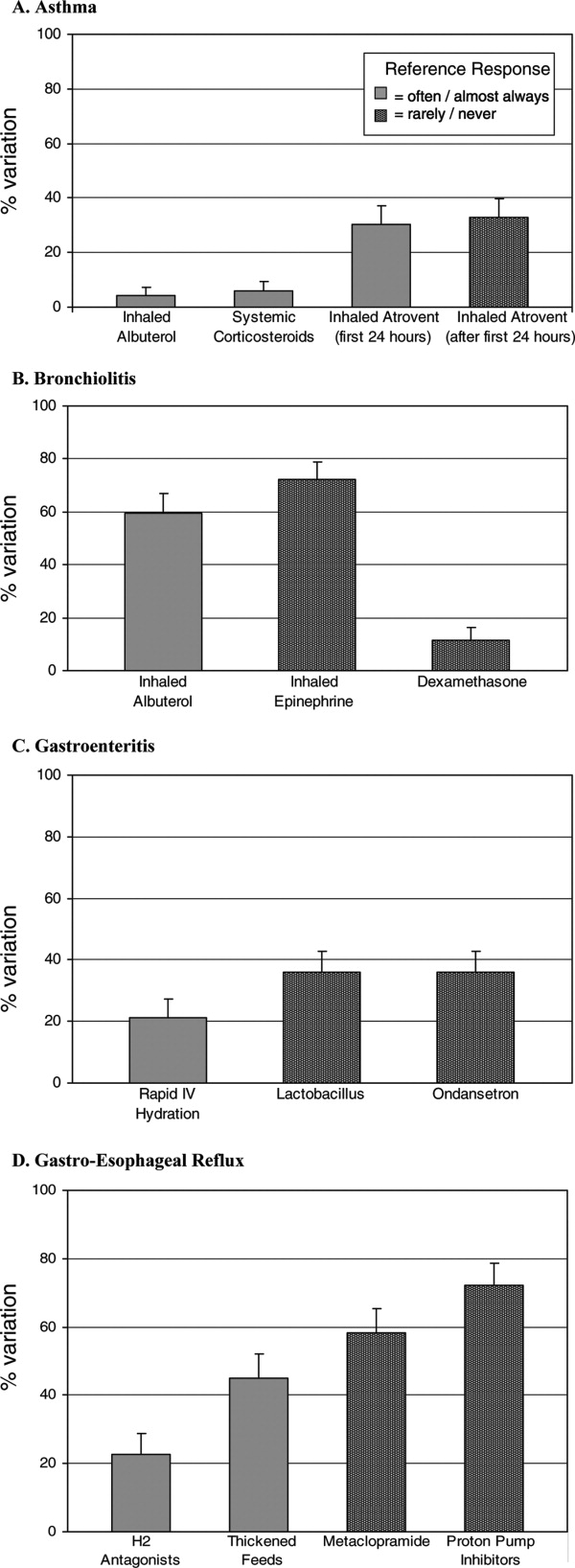

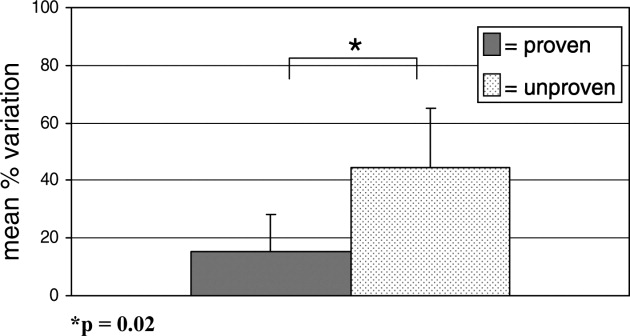

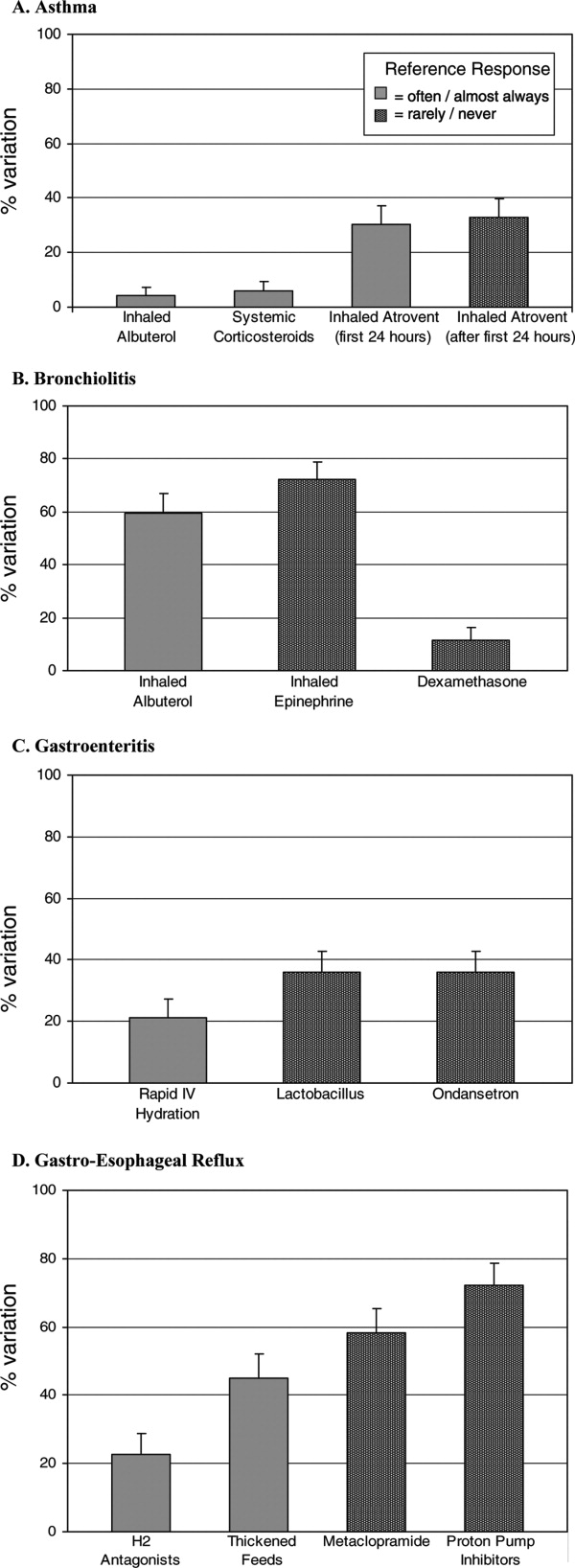

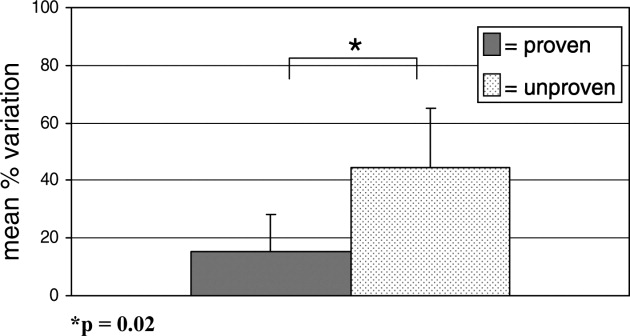

Variation in reported management: asthma

(Figure 1, Panel A). Relatively little variation existed in reported use of the 4 asthma therapies studied. Only 4.4% (95% CI, 1.4‐7.4%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of using inhaled albuterol often or almost always in the care of inpatients with asthma, and only 6.0% (2.5‐9.5%) of respondents did not report using systemic corticosteroids often or almost always. Variation in reported use of ipratropium was somewhat higher.

Bronchiolitis

(Figure 1B). By contrast, variation in reported use of inhaled therapies for bronchiolitis was high, with many respondents reporting that they often or always used inhaled albuterol or epinephrine, while many others reported rarely or never using them. There was 59.6% (52.4‐66.8%) variation from the reference response of often/almost always using inhaled albuterol, and 72.2% (65.6‐78.8%) variation from the reference response of never/rarely using inhaled epinephrine. Only 11.6% (6.9‐16.3%) of respondents, however, varied from the reference response of using dexamethasone more than rarely in the care of children with bronchiolitis.

Gastroenteritis

(Figure 1C). Moderate variability existed in the reported use of the 3 studied therapies for children hospitalized with gastroenteritis. 21.1% (15.1‐27.1%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of often/almost always using IV hydration; 35.9% (28.9‐42.9%) did not provide the reference response of never or rarely using lactobacillus; likewise, 35.9% (28.9‐42.9%) did not provide the reference response of never or rarely using ondansetron.

Gastro‐Esophageal Reflux Disease

(Figure 1, Panel D). There was moderate to high variability in the reported management of GERD. 22.8% (16.7‐28.9%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of often/almost always using H2 antagonists, and 44.9% (37.6‐52.2%) did not report often/almost always using thickened feeds in the care of these children. 58.3% (51.1‐65.5%) and 72.1% (65.5‐78.7%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of never/rarely using metoclopramide and proton pump inhibitors, respectively.

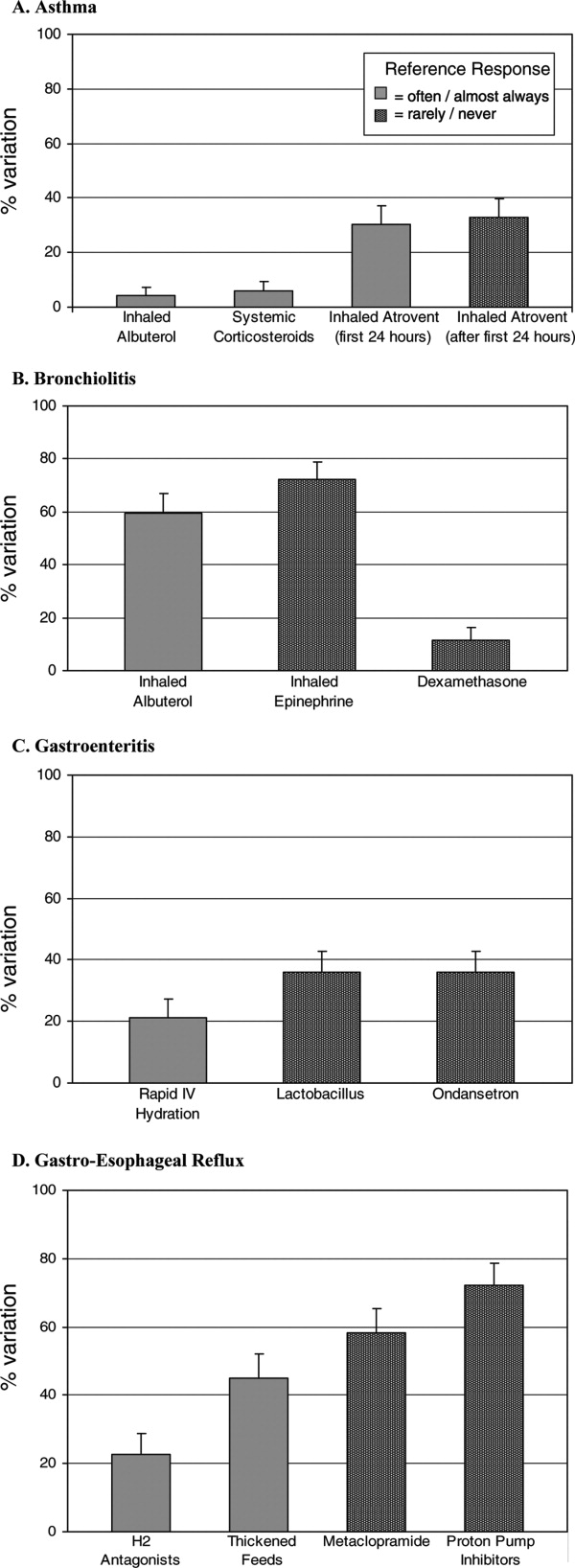

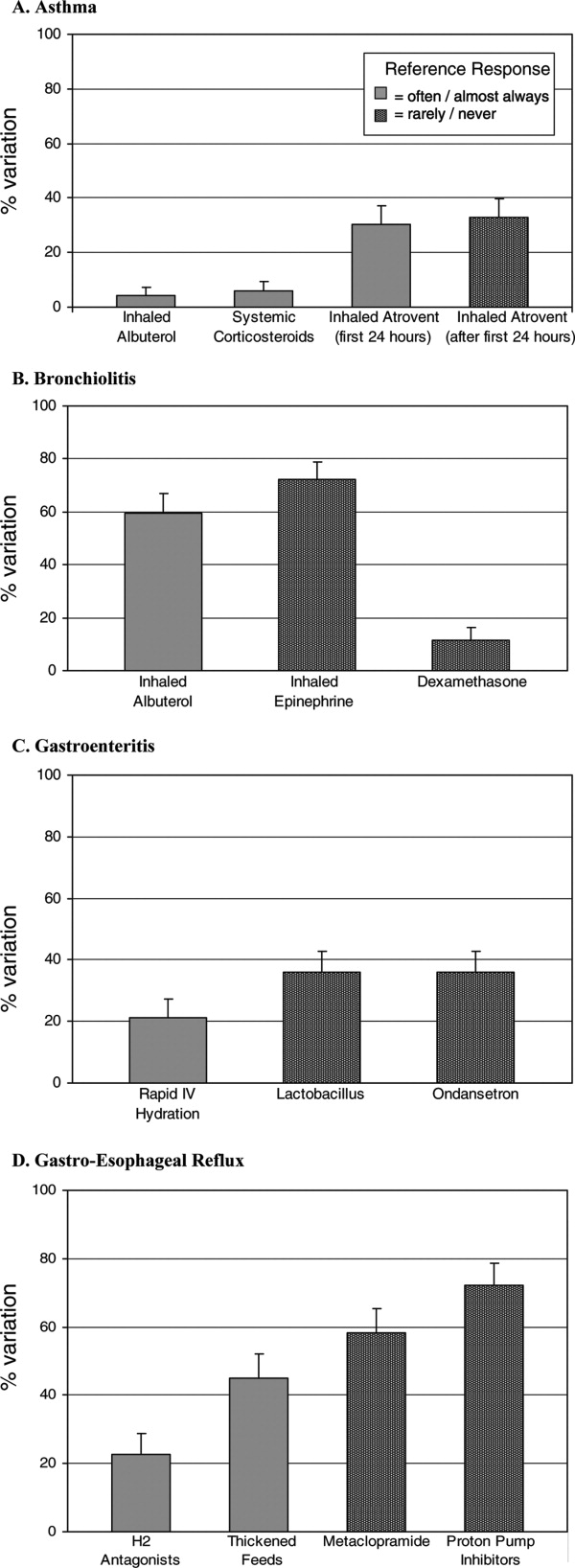

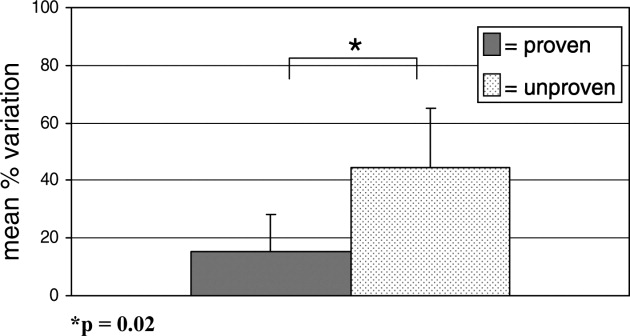

Proven vs. Unproven Therapies

(Figure 2). Variation in reported use of therapies of unproven benefit was significantly higher than variation in reported use of the 4 proven therapies (albuterol, corticosteroids, and ipratropium in the first 24 h for asthma; IV re‐hydration for gastroenteritis). The mean variation in reported use of unproven therapies was 44.6 20.5%, compared with 15.5 12.5% variation in reported use of therapies of proven benefit (p = 0.02).

As a sensitivity analysis, the use of thickened feeds as a therapy for GERD was re‐categorized as proven and the above analysis repeated, for the reasons outlined in the methods section. This did not alter the identified relationship between variability and the evidence base fundamentally; hospitalists' reported variation in use of therapies of unproven benefit in this sensitivity analysis was 44.6 21.7%, compared with 21.4 17.0% variation in reported use of proven therapies (p = 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Substantial variation exists in the inpatient management of common pediatric diseases. Although we have previously found less reported variability in pediatric hospitalists' practices than in those of community‐based pediatricians,20 the current study demonstrates a high degree of reported variation even among a cohort of inpatient specialists. Importantly, however, reported variation was found to be significantly less for those inpatient therapies supported by a robust evidence base.

Bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, asthma, and GERD are extremely common causes of pediatric hospitalization throughout the developed world.2125 Our finding of high reported variability in the routine care of all of these conditions except asthma is concerning, as it suggests that experts do not agree on how to manage children hospitalized with even the most common childhood diseases. While we hypothesized that there would be some variation in the use of therapies whose benefit has not been well established, the high degree of variation observed is of concern because it indicates that an insufficient evidentiary base exists to support much of our day‐to‐day practice. Some variation in practice in response to differing clinical presentations is both expected and desirable, but it is remarkable that variance in practice was significantly less for the most evidence‐based therapies than for those grounded less firmly in science, suggesting that the variation identified here is not justifiable variation based on appropriate responses to atypical clinical presentations, but uncertainty in the absence of clear data. Such undesired variability may decrease system reliability (introducing avoidable opportunity for error),26 and lead to under‐use of needed therapies as well as overuse of unnecessary therapies.1

Our work extends prior research that has identified wide variation in patterns of hospital admission, use of hospital resources, and processes of inpatient care,2732 by documenting reported variation in the use of common inpatient therapies. Rates of hospital admission may vary by as much as 7‐fold across regions.33 Our study demonstrates that wide variation exists not only in admission rates, but in reported inpatient care processes for some of the most common diseases seen in pediatric hospitals. Our study also supports the hypothesis that variation in care may be driven by gaps in knowledge.32 Among hospitalists, we found the strength of the evidence base to be a major determinant of reported variability.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data presented here are derived from provider self‐reports, which may not fully reflect actual practice. In the case of the few proven therapies studied, reporting bias could lead to an over‐reporting of adherence to evidence‐based standards of care. Like our study, however, prior studies have found that hospital‐based providers fairly consistently comply with evidence‐based practice recommendations for acute asthma care,34, 35 supporting our finding that variation in acute asthma care (which represented 3 of our 4 proven therapies) is low in this setting.

Another limitation is that classifications of therapies as proven or unproven change as the evidence base evolves. Of particular relevance to this study, the use of thickened feeds as a therapy for GERD, originally classified as being of unknown effectiveness, was reclassified by Clinical Evidence during the course of the study as likely to be beneficial. The relationship we identified between proven therapies and degree of variability in care did not change when we conducted a sensitivity analysis re‐categorizing this therapy as proven, but precisely quantifying variation is complicated by continuous changes in the state of the evidence.

Pediatric hospitalist systems have been found consistently to improve the efficiency of care,9 yet this study suggests that considerable variation in hospitalists' management of key conditions remains. The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network was formed in 2002 to improve the care of hospitalized children and the quality of inpatient practice by developing an evidence base for inpatient pediatric care. Ongoing multi‐center research efforts through PRIS and other research networks are beginning to critically evaluate therapies used in the management of common pediatric conditions. Rigorous studies of the processes and outcomes of pediatric hospital care will inform inpatient pediatric practice, and ultimately improve the care of hospitalized children. The current study strongly affirms the urgent need to establish such an evidence base. Without data to inform optimal care, efforts to reduce undesirable variation in care and improve care quality cannot be fully realized.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their thanks to the hospitalists and members of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network who participated in this research, as well as the Children's National Medical Center and Children's Hospital Boston Inpatient Pediatrics Services, who provided funding to support this study. Special thanks to the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association (APA), for its core support of the PRIS Network. Dr. Landrigan is the recipient of a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ K08 HS13333). Dr. Conway is the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Grant. All researchers were independent from the funding agencies; the academic medical centers named above, APA, and AHRQ had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

- Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, D.C.:National Academic Press,2001.

- ..Reducing variation in surgical care.BMJ2005;330:1401–1402.

- ,,,.Variation in use of video assisted thoracic surgery in the United Kingdom.BMJ2004;329:1011–1012.

- ,..The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N. Engl J Med1996;335:514–517.

- ,..Hospitalism in the USA.Lancet1999;353:1902.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Growth of Hospital Medicine Nationwide. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Media/GrowthofHospitalMedicineNationwide/Growth_of_Hospital_M.htm. Accessed April 11,2007.

- .The changing face of hospital practice.Med Econ2002;79:72–79.

- ,..The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA2002;287:487–494.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics2006;117:1736–1744.

- ,,,,,.Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes.Ann Intern Med2002;137:859–865.

- ,,,,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med2002;137:866–874.

- ,.Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service: impact on length of stay and hospital charges.Pediatrics2000;105:478–484.

- ,,,,,,, and .Impact of an HMO hospitalist system in academic pediatrics.Pediatrics2002;110:720–728.

- ,, and .Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service by APR‐DRG's: impact on length of stay and hospital charges.Pediatr Research2001;49(suppl),691.

- ,,.Pediatric hospitalists: quality care for the underserved?Am J Med Qual2001;16:174–180.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila)2001;40:653–660.

- ,,, and .Hospitalist care of medically complex children.Pediatr Research2004;55(suppl),1789.

- ,,.Hospital‐based and community pediatricians: comparing outcomes for asthma and bronchiolitis.J Clin Outcomes Manage1997;4:21–24.

- Godlee F,Tovey D,Bedford M, et al., eds.Clinical Evidence: The International Source of the Best Available Evidence for Effective Health Care.London, United Kingdom:BMJ Publishing Group;2004.

- ,,,,,.Variations in management of common inpatient pediatric illnesses: hospitalists and community pediatricians.Pediatrics2006;118:441–447.

- ,,,,.Contribution of RSV to bronchiolitis and pneumonia‐associated hospitalizations in English children, April 1995‐March 1998.Epidemiol Infect2002;129:99–106.

- ,,.Direct medical costs of bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States.Pediatrics2006;118:2418–2423.

- ,,,,,.Multicenter Prospective Study of the Burden of Rotavirus Acute Gastroenteritis in Europe, 2004‐2005: The REVEAL Study.J Infect Dis2007;195Suppl 1:S4–S16.

- .The state of childhood asthma, United States, 1980‐2005.Adv.Data.2006;1–24.

- ,.Gastroesophageal reflux in children: pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and role of proton pump inhibitors in treatment.Paediatr Drugs2002;4:673–685.

- ,,,.Reliability science and patient safety.Pediatr Clin North Am2006;53:1121–1133.

- Wennberg JE and McAndrew Cooper M, eds.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United States.Hanover, NH, USA:Health Forum, Inc.,1999.

- ,,,,,.Variations in rates of hospitalization of children in three urban communities.N Engl J Med1989;320:1183–1187.

- ,,,,,.Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States.BMJ2004;328:607.

- ,,,,,, et al.Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network: 1996‐1997.Pediatrics2000;106:1070–1079.

- ,,,.Evaluation of febrile children with petechial rashes: is there consensus among pediatricians?Pediatr Infect Dis J1998;17:1135–1140.

- ,,,,,, et al.Practice variation among pediatric emergency departments in the treatment of bronchiolitis.Acad Emerg Med2004;11:353–360.

- ,,,.Paediatric inpatient utilisation in a district general hospital.Arch Dis Child1994;70:488–492.

- ,,,.Emergency department asthma: compliance with an evidence‐based management algorithm.Ann Acad Med Singapore2002;31:419–424.

- ,,.Is the practice of paediatric inpatient medicine evidence‐based?J Paediatr Child Health2002;38:347–351.

Reduction of undesirable variation in care has been a major focus of systematic efforts to improve the quality of the healthcare system.13 The emergence of hospitalists, physicians specializing in the care of hospitalized patients, was spurred by a desire to streamline care and reduce variability in hospital management of common diseases.4, 5 Over the past decade, hospitalist systems have become a leading vehicle for care delivery.4, 6, 7 It remains unclear, however, whether implementation of hospitalist systems has lessened undesirable variation in the inpatient management of common diseases.

While systematic reviews have found costs and hospital length of stay to be 10‐15% lower in both pediatric and internal medicine hospitalist systems, few studies have adequately assessed the processes or quality of care in hospitalist systems.8, 9 Two internal medicine studies have found decreased mortality in hospitalist systems, but the mechanism by which hospitalists apparently achieved these gains is unclear.10, 11 Even less is known about care processes or quality in pediatric hospitalist systems. Death is a rare occurrence in pediatric ward settings, and the seven studies conducted to date comparing pediatric hospitalist and traditional systems have been universally underpowered to detect differences in mortality.9, 1218 There is a need to better understand care processes as a first step in understanding and improving quality of care in hospitalist systems.19

The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network was formed to improve the quality of care for hospitalized children through collaborative clinical research. In this study, we sought to study variation in the care of common pediatric conditions among a cohort of pediatric hospitalists. We have previously reported that less variability exists in hospitalists' reported management of inpatient conditions than in the reported management of these same conditions by community‐based pediatricians,20 but we were concerned that substantial undesirable variation (ie, variation in practice due to uncertainty or unsubstantiated local practice traditions, rather than justified variation in care based on different risks of harms or benefits in different patients) may still exist among hospitalists. We therefore conducted a study: 1) to investigate variation in hospitalists' reported use of common inpatient therapies, and 2) to test the hypothesis that greater variation exists in hospitalists' reported use of inpatient therapies of unproven benefit than in those therapies proven to be beneficial.

METHODS

Survey Design and Administration

In 2003, we designed the PRIS Survey to collect data on hospitalists' backgrounds, practices, and training needs, as well as their management of common pediatric conditions. For the current study, we chose a priori to evaluate hospitalists' use of 14 therapies in the management of 4 common conditions: asthma, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and gastro‐esophageal reflux disease (GERD) (Table 1). These four conditions were chosen for study because they were among the top discharge diagnoses (primary and secondary) from the inpatient services at 2 of the authors' institutions (Children's Hospital Boston and Children's Hospital San Diego) during the year before administration of the survey, and because a discrete set of therapeutic agents are commonly used in their management. Respondents were asked to report the frequency with which they used each of the 14 therapies of interest on 5‐point Likert scales (from 1=never to 5=almost always). The survey initially developed was piloted with a small group of hospitalists and pediatricians, and a final version incorporating revisions was subsequently administered to all pediatric hospitalists in the US and Canada identified through any of 3 sources: 1) the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) list of participants; 2) the Society for Hospital Medicine (SHM) pediatric hospital medicine e‐mail listserv; and 3) the list of all attendees of the first national pediatric hospitalist conference sponsored by the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association (APA), SHM, and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP); this meeting was held in San Antonio, Texas, USA in November 2003. Individuals identified through more than 1 of these groups were counted only once. Potential participants were assured that individual responses would be kept confidential, and were e‐mailed an access code to participate in the online survey, using a secure web‐based interface; a paper‐based version was also made available to those who preferred to respond in this manner. Regular reminder notices were sent to all non‐responders. Further details regarding PRIS Survey recruitment and study methods have been published previously.20

| Condition | Therapy | BMJ clinical evidence Treatment effect categorization* | Study classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Asthma | Inhaled albuterol | Beneficial | Proven |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Beneficial | Proven | |

| Inhaled ipratropium in the first 24 hours of hospitalization | Beneficial | Proven | |

| Inhaled ipratropium after the first 24 hours of hospitalization | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Bronchiolitis | Inhaled albuterol | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven |

| Inhaled epinephrine | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Gastroenteritis | Intravenous hydration | Beneficial | Proven |

| Lactobacillus | Not assessed | Unproven | |

| Ondansetron | Not assessed | Unproven | |

| Gastro‐Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) | H2 histamine‐receptor antagonists | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven |

| Thickened feeds | Unknown effectiveness Likely to be beneficial | Unproven Proven | |

| Metoclopramide | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Proton‐pump inhibitors | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

DefinitionsReference Responses and Percent Variation

To measure variation in reported management, we first sought to determine a reference response for each therapy of interest. Since the evidence base for most of the therapies we studied is weak, it was not possible to determine a gold standard response for each therapy. Instead, we sought to measure the degree of divergence from a reference response for each therapy in the following manner. First, to simplify analyses, we collapsed our five‐category Likert scale into three categories (never/rarely, sometimes, and often/almost always). We then defined the reference response for each therapy to be never/rarely or often/almost always, whichever of the 2 was more frequently selected by respondents; sometimes was not used as a reference category, as reporting use of a particular therapy sometimes indicated substantial variability even within an individual's own practice.

Classification of therapies as proven or unproven.

To classify each of the 14 studied therapies as being of proven or unproven, we used the British Medical Journal's publication Clinical Evidence.19 We chose to use Clinical Evidence as an evidence‐based reference because it provides rigorously developed, systematic analyses of therapeutic management options for multiple common pediatric conditions, and organizes recommendations in a straightforward manner. Four of the 14 therapies had been determined on systematic review to be proven beneficial at the time of study design: systemic corticosteroids, inhaled albuterol, and ipratropium (in the first 24 h) in the care of children with asthma; and IV hydration in the care of children with acute gastroenteritis. The remaining 10 therapies were either considered to be of unknown effectiveness or had not been formally evaluated by Clinical Evidence, and were hence considered unproven for this study (Table 1). Of note, the use of thickened feeds in the treatment of children with GERD had been determined to be of unknown effectiveness at the time of study design, but was reclassified as likely to be beneficial during the course of the study.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to report respondents' demographic characteristics and work environments, as well as variation in their reported use of each of the 14 therapies. Variation in hospitalists' use of proven versus unproven therapies was compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, as it was distributed non‐normally. For our primary analysis, the use of thickened feeds in GERD was considered unproven, but a sensitivity analysis was conducted reclassifying it as proven in light of the evolving literature on its use and its consequent reclassification in Clinical Evidence.(SAS Version 9.1, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

213 of the 320 individuals identified through the 3 lists of pediatric hospitalists (67%) responded to the survey. Of these, 198 (93%) identified themselves as hospitalists and were therefore included. As previously reported,20 53% of respondents were male, 55% worked in academic training environments, and 47% had completed advanced training (fellowship) beyond their core pediatric training (residency training); respondents reported completing residency training 11 9 (mean, standard deviation) years prior to the survey, and spending 176 72 days per year in the care of hospitalized patients.

Variation in reported management: asthma

(Figure 1, Panel A). Relatively little variation existed in reported use of the 4 asthma therapies studied. Only 4.4% (95% CI, 1.4‐7.4%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of using inhaled albuterol often or almost always in the care of inpatients with asthma, and only 6.0% (2.5‐9.5%) of respondents did not report using systemic corticosteroids often or almost always. Variation in reported use of ipratropium was somewhat higher.

Bronchiolitis

(Figure 1B). By contrast, variation in reported use of inhaled therapies for bronchiolitis was high, with many respondents reporting that they often or always used inhaled albuterol or epinephrine, while many others reported rarely or never using them. There was 59.6% (52.4‐66.8%) variation from the reference response of often/almost always using inhaled albuterol, and 72.2% (65.6‐78.8%) variation from the reference response of never/rarely using inhaled epinephrine. Only 11.6% (6.9‐16.3%) of respondents, however, varied from the reference response of using dexamethasone more than rarely in the care of children with bronchiolitis.

Gastroenteritis

(Figure 1C). Moderate variability existed in the reported use of the 3 studied therapies for children hospitalized with gastroenteritis. 21.1% (15.1‐27.1%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of often/almost always using IV hydration; 35.9% (28.9‐42.9%) did not provide the reference response of never or rarely using lactobacillus; likewise, 35.9% (28.9‐42.9%) did not provide the reference response of never or rarely using ondansetron.

Gastro‐Esophageal Reflux Disease

(Figure 1, Panel D). There was moderate to high variability in the reported management of GERD. 22.8% (16.7‐28.9%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of often/almost always using H2 antagonists, and 44.9% (37.6‐52.2%) did not report often/almost always using thickened feeds in the care of these children. 58.3% (51.1‐65.5%) and 72.1% (65.5‐78.7%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of never/rarely using metoclopramide and proton pump inhibitors, respectively.

Proven vs. Unproven Therapies

(Figure 2). Variation in reported use of therapies of unproven benefit was significantly higher than variation in reported use of the 4 proven therapies (albuterol, corticosteroids, and ipratropium in the first 24 h for asthma; IV re‐hydration for gastroenteritis). The mean variation in reported use of unproven therapies was 44.6 20.5%, compared with 15.5 12.5% variation in reported use of therapies of proven benefit (p = 0.02).

As a sensitivity analysis, the use of thickened feeds as a therapy for GERD was re‐categorized as proven and the above analysis repeated, for the reasons outlined in the methods section. This did not alter the identified relationship between variability and the evidence base fundamentally; hospitalists' reported variation in use of therapies of unproven benefit in this sensitivity analysis was 44.6 21.7%, compared with 21.4 17.0% variation in reported use of proven therapies (p = 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Substantial variation exists in the inpatient management of common pediatric diseases. Although we have previously found less reported variability in pediatric hospitalists' practices than in those of community‐based pediatricians,20 the current study demonstrates a high degree of reported variation even among a cohort of inpatient specialists. Importantly, however, reported variation was found to be significantly less for those inpatient therapies supported by a robust evidence base.

Bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, asthma, and GERD are extremely common causes of pediatric hospitalization throughout the developed world.2125 Our finding of high reported variability in the routine care of all of these conditions except asthma is concerning, as it suggests that experts do not agree on how to manage children hospitalized with even the most common childhood diseases. While we hypothesized that there would be some variation in the use of therapies whose benefit has not been well established, the high degree of variation observed is of concern because it indicates that an insufficient evidentiary base exists to support much of our day‐to‐day practice. Some variation in practice in response to differing clinical presentations is both expected and desirable, but it is remarkable that variance in practice was significantly less for the most evidence‐based therapies than for those grounded less firmly in science, suggesting that the variation identified here is not justifiable variation based on appropriate responses to atypical clinical presentations, but uncertainty in the absence of clear data. Such undesired variability may decrease system reliability (introducing avoidable opportunity for error),26 and lead to under‐use of needed therapies as well as overuse of unnecessary therapies.1

Our work extends prior research that has identified wide variation in patterns of hospital admission, use of hospital resources, and processes of inpatient care,2732 by documenting reported variation in the use of common inpatient therapies. Rates of hospital admission may vary by as much as 7‐fold across regions.33 Our study demonstrates that wide variation exists not only in admission rates, but in reported inpatient care processes for some of the most common diseases seen in pediatric hospitals. Our study also supports the hypothesis that variation in care may be driven by gaps in knowledge.32 Among hospitalists, we found the strength of the evidence base to be a major determinant of reported variability.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data presented here are derived from provider self‐reports, which may not fully reflect actual practice. In the case of the few proven therapies studied, reporting bias could lead to an over‐reporting of adherence to evidence‐based standards of care. Like our study, however, prior studies have found that hospital‐based providers fairly consistently comply with evidence‐based practice recommendations for acute asthma care,34, 35 supporting our finding that variation in acute asthma care (which represented 3 of our 4 proven therapies) is low in this setting.

Another limitation is that classifications of therapies as proven or unproven change as the evidence base evolves. Of particular relevance to this study, the use of thickened feeds as a therapy for GERD, originally classified as being of unknown effectiveness, was reclassified by Clinical Evidence during the course of the study as likely to be beneficial. The relationship we identified between proven therapies and degree of variability in care did not change when we conducted a sensitivity analysis re‐categorizing this therapy as proven, but precisely quantifying variation is complicated by continuous changes in the state of the evidence.

Pediatric hospitalist systems have been found consistently to improve the efficiency of care,9 yet this study suggests that considerable variation in hospitalists' management of key conditions remains. The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network was formed in 2002 to improve the care of hospitalized children and the quality of inpatient practice by developing an evidence base for inpatient pediatric care. Ongoing multi‐center research efforts through PRIS and other research networks are beginning to critically evaluate therapies used in the management of common pediatric conditions. Rigorous studies of the processes and outcomes of pediatric hospital care will inform inpatient pediatric practice, and ultimately improve the care of hospitalized children. The current study strongly affirms the urgent need to establish such an evidence base. Without data to inform optimal care, efforts to reduce undesirable variation in care and improve care quality cannot be fully realized.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their thanks to the hospitalists and members of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network who participated in this research, as well as the Children's National Medical Center and Children's Hospital Boston Inpatient Pediatrics Services, who provided funding to support this study. Special thanks to the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association (APA), for its core support of the PRIS Network. Dr. Landrigan is the recipient of a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ K08 HS13333). Dr. Conway is the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Grant. All researchers were independent from the funding agencies; the academic medical centers named above, APA, and AHRQ had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Reduction of undesirable variation in care has been a major focus of systematic efforts to improve the quality of the healthcare system.13 The emergence of hospitalists, physicians specializing in the care of hospitalized patients, was spurred by a desire to streamline care and reduce variability in hospital management of common diseases.4, 5 Over the past decade, hospitalist systems have become a leading vehicle for care delivery.4, 6, 7 It remains unclear, however, whether implementation of hospitalist systems has lessened undesirable variation in the inpatient management of common diseases.

While systematic reviews have found costs and hospital length of stay to be 10‐15% lower in both pediatric and internal medicine hospitalist systems, few studies have adequately assessed the processes or quality of care in hospitalist systems.8, 9 Two internal medicine studies have found decreased mortality in hospitalist systems, but the mechanism by which hospitalists apparently achieved these gains is unclear.10, 11 Even less is known about care processes or quality in pediatric hospitalist systems. Death is a rare occurrence in pediatric ward settings, and the seven studies conducted to date comparing pediatric hospitalist and traditional systems have been universally underpowered to detect differences in mortality.9, 1218 There is a need to better understand care processes as a first step in understanding and improving quality of care in hospitalist systems.19

The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network was formed to improve the quality of care for hospitalized children through collaborative clinical research. In this study, we sought to study variation in the care of common pediatric conditions among a cohort of pediatric hospitalists. We have previously reported that less variability exists in hospitalists' reported management of inpatient conditions than in the reported management of these same conditions by community‐based pediatricians,20 but we were concerned that substantial undesirable variation (ie, variation in practice due to uncertainty or unsubstantiated local practice traditions, rather than justified variation in care based on different risks of harms or benefits in different patients) may still exist among hospitalists. We therefore conducted a study: 1) to investigate variation in hospitalists' reported use of common inpatient therapies, and 2) to test the hypothesis that greater variation exists in hospitalists' reported use of inpatient therapies of unproven benefit than in those therapies proven to be beneficial.

METHODS

Survey Design and Administration

In 2003, we designed the PRIS Survey to collect data on hospitalists' backgrounds, practices, and training needs, as well as their management of common pediatric conditions. For the current study, we chose a priori to evaluate hospitalists' use of 14 therapies in the management of 4 common conditions: asthma, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and gastro‐esophageal reflux disease (GERD) (Table 1). These four conditions were chosen for study because they were among the top discharge diagnoses (primary and secondary) from the inpatient services at 2 of the authors' institutions (Children's Hospital Boston and Children's Hospital San Diego) during the year before administration of the survey, and because a discrete set of therapeutic agents are commonly used in their management. Respondents were asked to report the frequency with which they used each of the 14 therapies of interest on 5‐point Likert scales (from 1=never to 5=almost always). The survey initially developed was piloted with a small group of hospitalists and pediatricians, and a final version incorporating revisions was subsequently administered to all pediatric hospitalists in the US and Canada identified through any of 3 sources: 1) the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) list of participants; 2) the Society for Hospital Medicine (SHM) pediatric hospital medicine e‐mail listserv; and 3) the list of all attendees of the first national pediatric hospitalist conference sponsored by the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association (APA), SHM, and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP); this meeting was held in San Antonio, Texas, USA in November 2003. Individuals identified through more than 1 of these groups were counted only once. Potential participants were assured that individual responses would be kept confidential, and were e‐mailed an access code to participate in the online survey, using a secure web‐based interface; a paper‐based version was also made available to those who preferred to respond in this manner. Regular reminder notices were sent to all non‐responders. Further details regarding PRIS Survey recruitment and study methods have been published previously.20

| Condition | Therapy | BMJ clinical evidence Treatment effect categorization* | Study classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Asthma | Inhaled albuterol | Beneficial | Proven |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Beneficial | Proven | |

| Inhaled ipratropium in the first 24 hours of hospitalization | Beneficial | Proven | |

| Inhaled ipratropium after the first 24 hours of hospitalization | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Bronchiolitis | Inhaled albuterol | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven |

| Inhaled epinephrine | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Gastroenteritis | Intravenous hydration | Beneficial | Proven |

| Lactobacillus | Not assessed | Unproven | |

| Ondansetron | Not assessed | Unproven | |

| Gastro‐Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) | H2 histamine‐receptor antagonists | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven |

| Thickened feeds | Unknown effectiveness Likely to be beneficial | Unproven Proven | |

| Metoclopramide | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

| Proton‐pump inhibitors | Unknown effectiveness | Unproven | |

DefinitionsReference Responses and Percent Variation

To measure variation in reported management, we first sought to determine a reference response for each therapy of interest. Since the evidence base for most of the therapies we studied is weak, it was not possible to determine a gold standard response for each therapy. Instead, we sought to measure the degree of divergence from a reference response for each therapy in the following manner. First, to simplify analyses, we collapsed our five‐category Likert scale into three categories (never/rarely, sometimes, and often/almost always). We then defined the reference response for each therapy to be never/rarely or often/almost always, whichever of the 2 was more frequently selected by respondents; sometimes was not used as a reference category, as reporting use of a particular therapy sometimes indicated substantial variability even within an individual's own practice.

Classification of therapies as proven or unproven.

To classify each of the 14 studied therapies as being of proven or unproven, we used the British Medical Journal's publication Clinical Evidence.19 We chose to use Clinical Evidence as an evidence‐based reference because it provides rigorously developed, systematic analyses of therapeutic management options for multiple common pediatric conditions, and organizes recommendations in a straightforward manner. Four of the 14 therapies had been determined on systematic review to be proven beneficial at the time of study design: systemic corticosteroids, inhaled albuterol, and ipratropium (in the first 24 h) in the care of children with asthma; and IV hydration in the care of children with acute gastroenteritis. The remaining 10 therapies were either considered to be of unknown effectiveness or had not been formally evaluated by Clinical Evidence, and were hence considered unproven for this study (Table 1). Of note, the use of thickened feeds in the treatment of children with GERD had been determined to be of unknown effectiveness at the time of study design, but was reclassified as likely to be beneficial during the course of the study.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to report respondents' demographic characteristics and work environments, as well as variation in their reported use of each of the 14 therapies. Variation in hospitalists' use of proven versus unproven therapies was compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, as it was distributed non‐normally. For our primary analysis, the use of thickened feeds in GERD was considered unproven, but a sensitivity analysis was conducted reclassifying it as proven in light of the evolving literature on its use and its consequent reclassification in Clinical Evidence.(SAS Version 9.1, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

213 of the 320 individuals identified through the 3 lists of pediatric hospitalists (67%) responded to the survey. Of these, 198 (93%) identified themselves as hospitalists and were therefore included. As previously reported,20 53% of respondents were male, 55% worked in academic training environments, and 47% had completed advanced training (fellowship) beyond their core pediatric training (residency training); respondents reported completing residency training 11 9 (mean, standard deviation) years prior to the survey, and spending 176 72 days per year in the care of hospitalized patients.

Variation in reported management: asthma

(Figure 1, Panel A). Relatively little variation existed in reported use of the 4 asthma therapies studied. Only 4.4% (95% CI, 1.4‐7.4%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of using inhaled albuterol often or almost always in the care of inpatients with asthma, and only 6.0% (2.5‐9.5%) of respondents did not report using systemic corticosteroids often or almost always. Variation in reported use of ipratropium was somewhat higher.

Bronchiolitis

(Figure 1B). By contrast, variation in reported use of inhaled therapies for bronchiolitis was high, with many respondents reporting that they often or always used inhaled albuterol or epinephrine, while many others reported rarely or never using them. There was 59.6% (52.4‐66.8%) variation from the reference response of often/almost always using inhaled albuterol, and 72.2% (65.6‐78.8%) variation from the reference response of never/rarely using inhaled epinephrine. Only 11.6% (6.9‐16.3%) of respondents, however, varied from the reference response of using dexamethasone more than rarely in the care of children with bronchiolitis.

Gastroenteritis

(Figure 1C). Moderate variability existed in the reported use of the 3 studied therapies for children hospitalized with gastroenteritis. 21.1% (15.1‐27.1%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of often/almost always using IV hydration; 35.9% (28.9‐42.9%) did not provide the reference response of never or rarely using lactobacillus; likewise, 35.9% (28.9‐42.9%) did not provide the reference response of never or rarely using ondansetron.

Gastro‐Esophageal Reflux Disease

(Figure 1, Panel D). There was moderate to high variability in the reported management of GERD. 22.8% (16.7‐28.9%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of often/almost always using H2 antagonists, and 44.9% (37.6‐52.2%) did not report often/almost always using thickened feeds in the care of these children. 58.3% (51.1‐65.5%) and 72.1% (65.5‐78.7%) of respondents did not provide the reference response of never/rarely using metoclopramide and proton pump inhibitors, respectively.

Proven vs. Unproven Therapies

(Figure 2). Variation in reported use of therapies of unproven benefit was significantly higher than variation in reported use of the 4 proven therapies (albuterol, corticosteroids, and ipratropium in the first 24 h for asthma; IV re‐hydration for gastroenteritis). The mean variation in reported use of unproven therapies was 44.6 20.5%, compared with 15.5 12.5% variation in reported use of therapies of proven benefit (p = 0.02).

As a sensitivity analysis, the use of thickened feeds as a therapy for GERD was re‐categorized as proven and the above analysis repeated, for the reasons outlined in the methods section. This did not alter the identified relationship between variability and the evidence base fundamentally; hospitalists' reported variation in use of therapies of unproven benefit in this sensitivity analysis was 44.6 21.7%, compared with 21.4 17.0% variation in reported use of proven therapies (p = 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Substantial variation exists in the inpatient management of common pediatric diseases. Although we have previously found less reported variability in pediatric hospitalists' practices than in those of community‐based pediatricians,20 the current study demonstrates a high degree of reported variation even among a cohort of inpatient specialists. Importantly, however, reported variation was found to be significantly less for those inpatient therapies supported by a robust evidence base.

Bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, asthma, and GERD are extremely common causes of pediatric hospitalization throughout the developed world.2125 Our finding of high reported variability in the routine care of all of these conditions except asthma is concerning, as it suggests that experts do not agree on how to manage children hospitalized with even the most common childhood diseases. While we hypothesized that there would be some variation in the use of therapies whose benefit has not been well established, the high degree of variation observed is of concern because it indicates that an insufficient evidentiary base exists to support much of our day‐to‐day practice. Some variation in practice in response to differing clinical presentations is both expected and desirable, but it is remarkable that variance in practice was significantly less for the most evidence‐based therapies than for those grounded less firmly in science, suggesting that the variation identified here is not justifiable variation based on appropriate responses to atypical clinical presentations, but uncertainty in the absence of clear data. Such undesired variability may decrease system reliability (introducing avoidable opportunity for error),26 and lead to under‐use of needed therapies as well as overuse of unnecessary therapies.1

Our work extends prior research that has identified wide variation in patterns of hospital admission, use of hospital resources, and processes of inpatient care,2732 by documenting reported variation in the use of common inpatient therapies. Rates of hospital admission may vary by as much as 7‐fold across regions.33 Our study demonstrates that wide variation exists not only in admission rates, but in reported inpatient care processes for some of the most common diseases seen in pediatric hospitals. Our study also supports the hypothesis that variation in care may be driven by gaps in knowledge.32 Among hospitalists, we found the strength of the evidence base to be a major determinant of reported variability.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data presented here are derived from provider self‐reports, which may not fully reflect actual practice. In the case of the few proven therapies studied, reporting bias could lead to an over‐reporting of adherence to evidence‐based standards of care. Like our study, however, prior studies have found that hospital‐based providers fairly consistently comply with evidence‐based practice recommendations for acute asthma care,34, 35 supporting our finding that variation in acute asthma care (which represented 3 of our 4 proven therapies) is low in this setting.

Another limitation is that classifications of therapies as proven or unproven change as the evidence base evolves. Of particular relevance to this study, the use of thickened feeds as a therapy for GERD, originally classified as being of unknown effectiveness, was reclassified by Clinical Evidence during the course of the study as likely to be beneficial. The relationship we identified between proven therapies and degree of variability in care did not change when we conducted a sensitivity analysis re‐categorizing this therapy as proven, but precisely quantifying variation is complicated by continuous changes in the state of the evidence.

Pediatric hospitalist systems have been found consistently to improve the efficiency of care,9 yet this study suggests that considerable variation in hospitalists' management of key conditions remains. The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network was formed in 2002 to improve the care of hospitalized children and the quality of inpatient practice by developing an evidence base for inpatient pediatric care. Ongoing multi‐center research efforts through PRIS and other research networks are beginning to critically evaluate therapies used in the management of common pediatric conditions. Rigorous studies of the processes and outcomes of pediatric hospital care will inform inpatient pediatric practice, and ultimately improve the care of hospitalized children. The current study strongly affirms the urgent need to establish such an evidence base. Without data to inform optimal care, efforts to reduce undesirable variation in care and improve care quality cannot be fully realized.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their thanks to the hospitalists and members of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network who participated in this research, as well as the Children's National Medical Center and Children's Hospital Boston Inpatient Pediatrics Services, who provided funding to support this study. Special thanks to the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association (APA), for its core support of the PRIS Network. Dr. Landrigan is the recipient of a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ K08 HS13333). Dr. Conway is the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Grant. All researchers were independent from the funding agencies; the academic medical centers named above, APA, and AHRQ had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

- Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, D.C.:National Academic Press,2001.

- ..Reducing variation in surgical care.BMJ2005;330:1401–1402.

- ,,,.Variation in use of video assisted thoracic surgery in the United Kingdom.BMJ2004;329:1011–1012.

- ,..The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N. Engl J Med1996;335:514–517.

- ,..Hospitalism in the USA.Lancet1999;353:1902.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Growth of Hospital Medicine Nationwide. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Media/GrowthofHospitalMedicineNationwide/Growth_of_Hospital_M.htm. Accessed April 11,2007.

- .The changing face of hospital practice.Med Econ2002;79:72–79.

- ,..The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA2002;287:487–494.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics2006;117:1736–1744.

- ,,,,,.Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes.Ann Intern Med2002;137:859–865.

- ,,,,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med2002;137:866–874.

- ,.Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service: impact on length of stay and hospital charges.Pediatrics2000;105:478–484.

- ,,,,,,, and .Impact of an HMO hospitalist system in academic pediatrics.Pediatrics2002;110:720–728.

- ,, and .Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service by APR‐DRG's: impact on length of stay and hospital charges.Pediatr Research2001;49(suppl),691.

- ,,.Pediatric hospitalists: quality care for the underserved?Am J Med Qual2001;16:174–180.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila)2001;40:653–660.

- ,,, and .Hospitalist care of medically complex children.Pediatr Research2004;55(suppl),1789.

- ,,.Hospital‐based and community pediatricians: comparing outcomes for asthma and bronchiolitis.J Clin Outcomes Manage1997;4:21–24.

- Godlee F,Tovey D,Bedford M, et al., eds.Clinical Evidence: The International Source of the Best Available Evidence for Effective Health Care.London, United Kingdom:BMJ Publishing Group;2004.

- ,,,,,.Variations in management of common inpatient pediatric illnesses: hospitalists and community pediatricians.Pediatrics2006;118:441–447.

- ,,,,.Contribution of RSV to bronchiolitis and pneumonia‐associated hospitalizations in English children, April 1995‐March 1998.Epidemiol Infect2002;129:99–106.

- ,,.Direct medical costs of bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States.Pediatrics2006;118:2418–2423.

- ,,,,,.Multicenter Prospective Study of the Burden of Rotavirus Acute Gastroenteritis in Europe, 2004‐2005: The REVEAL Study.J Infect Dis2007;195Suppl 1:S4–S16.

- .The state of childhood asthma, United States, 1980‐2005.Adv.Data.2006;1–24.

- ,.Gastroesophageal reflux in children: pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and role of proton pump inhibitors in treatment.Paediatr Drugs2002;4:673–685.

- ,,,.Reliability science and patient safety.Pediatr Clin North Am2006;53:1121–1133.

- Wennberg JE and McAndrew Cooper M, eds.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United States.Hanover, NH, USA:Health Forum, Inc.,1999.

- ,,,,,.Variations in rates of hospitalization of children in three urban communities.N Engl J Med1989;320:1183–1187.

- ,,,,,.Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States.BMJ2004;328:607.

- ,,,,,, et al.Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network: 1996‐1997.Pediatrics2000;106:1070–1079.

- ,,,.Evaluation of febrile children with petechial rashes: is there consensus among pediatricians?Pediatr Infect Dis J1998;17:1135–1140.

- ,,,,,, et al.Practice variation among pediatric emergency departments in the treatment of bronchiolitis.Acad Emerg Med2004;11:353–360.

- ,,,.Paediatric inpatient utilisation in a district general hospital.Arch Dis Child1994;70:488–492.

- ,,,.Emergency department asthma: compliance with an evidence‐based management algorithm.Ann Acad Med Singapore2002;31:419–424.

- ,,.Is the practice of paediatric inpatient medicine evidence‐based?J Paediatr Child Health2002;38:347–351.

- Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, D.C.:National Academic Press,2001.

- ..Reducing variation in surgical care.BMJ2005;330:1401–1402.

- ,,,.Variation in use of video assisted thoracic surgery in the United Kingdom.BMJ2004;329:1011–1012.

- ,..The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N. Engl J Med1996;335:514–517.

- ,..Hospitalism in the USA.Lancet1999;353:1902.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Growth of Hospital Medicine Nationwide. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Media/GrowthofHospitalMedicineNationwide/Growth_of_Hospital_M.htm. Accessed April 11,2007.

- .The changing face of hospital practice.Med Econ2002;79:72–79.

- ,..The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA2002;287:487–494.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics2006;117:1736–1744.

- ,,,,,.Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes.Ann Intern Med2002;137:859–865.

- ,,,,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med2002;137:866–874.

- ,.Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service: impact on length of stay and hospital charges.Pediatrics2000;105:478–484.

- ,,,,,,, and .Impact of an HMO hospitalist system in academic pediatrics.Pediatrics2002;110:720–728.

- ,, and .Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service by APR‐DRG's: impact on length of stay and hospital charges.Pediatr Research2001;49(suppl),691.

- ,,.Pediatric hospitalists: quality care for the underserved?Am J Med Qual2001;16:174–180.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila)2001;40:653–660.

- ,,, and .Hospitalist care of medically complex children.Pediatr Research2004;55(suppl),1789.

- ,,.Hospital‐based and community pediatricians: comparing outcomes for asthma and bronchiolitis.J Clin Outcomes Manage1997;4:21–24.

- Godlee F,Tovey D,Bedford M, et al., eds.Clinical Evidence: The International Source of the Best Available Evidence for Effective Health Care.London, United Kingdom:BMJ Publishing Group;2004.

- ,,,,,.Variations in management of common inpatient pediatric illnesses: hospitalists and community pediatricians.Pediatrics2006;118:441–447.

- ,,,,.Contribution of RSV to bronchiolitis and pneumonia‐associated hospitalizations in English children, April 1995‐March 1998.Epidemiol Infect2002;129:99–106.

- ,,.Direct medical costs of bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States.Pediatrics2006;118:2418–2423.

- ,,,,,.Multicenter Prospective Study of the Burden of Rotavirus Acute Gastroenteritis in Europe, 2004‐2005: The REVEAL Study.J Infect Dis2007;195Suppl 1:S4–S16.

- .The state of childhood asthma, United States, 1980‐2005.Adv.Data.2006;1–24.

- ,.Gastroesophageal reflux in children: pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and role of proton pump inhibitors in treatment.Paediatr Drugs2002;4:673–685.

- ,,,.Reliability science and patient safety.Pediatr Clin North Am2006;53:1121–1133.

- Wennberg JE and McAndrew Cooper M, eds.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United States.Hanover, NH, USA:Health Forum, Inc.,1999.

- ,,,,,.Variations in rates of hospitalization of children in three urban communities.N Engl J Med1989;320:1183–1187.

- ,,,,,.Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States.BMJ2004;328:607.

- ,,,,,, et al.Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network: 1996‐1997.Pediatrics2000;106:1070–1079.

- ,,,.Evaluation of febrile children with petechial rashes: is there consensus among pediatricians?Pediatr Infect Dis J1998;17:1135–1140.

- ,,,,,, et al.Practice variation among pediatric emergency departments in the treatment of bronchiolitis.Acad Emerg Med2004;11:353–360.

- ,,,.Paediatric inpatient utilisation in a district general hospital.Arch Dis Child1994;70:488–492.

- ,,,.Emergency department asthma: compliance with an evidence‐based management algorithm.Ann Acad Med Singapore2002;31:419–424.

- ,,.Is the practice of paediatric inpatient medicine evidence‐based?J Paediatr Child Health2002;38:347–351.

Copyright © 2008 Society of Hospital Medicine