User login

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, is associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital. He is a former member of Team Hospitalist and has served as The Hospitalist's pediatric editor since 2012.

PHM16: Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leaders Kick Off 2016 Conference

Speaker: Lisa Zaoutis, MD, Pediatric Residency Program Director at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Amid the skyscrapers of the Windy City, Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) 2016 swept into town, bringing with it the denizens of pediatric hospitalist programs across the country. Some 1,150 attendees, comprised of hospitalists, PHM program leaders, and advanced care practitioners, gathered to educate and inspire one another in the the care of hospitalized children.

Dr. Lisa Zaoutis, director of the pediatric residency program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, kicked off the conference with the opening plenary. Initially titled “North Star and Space,” she quickly changed the title to, “Changing Our Minds.” Touching on the disconnect between positive experiences that bring physicians into PHM and negative experiences that often drive behavior, she started with the beginning, the evolution of our brains.

“We are wired toward the negative,” stated Dr. Zaoutis. “We are Teflon for positive experiences and Velcro for negative experiences.” In addition, negative experiences are more likely to be stored in our memories. “It’s easy to park negative experiences.”

Delving deeper into neuroanatomy, Dr. Zaoutis spoke of “amygdala hijack,” where chronic stress inherent to the professional lives of pediatric hospitalists lead to anxiety responses that are faster, more robust, and triggered more easily.

But all is not lost, asserted Dr. Zaoutis, as our brains are more plastic than previously known. The “neural Darwinism,” of our brains, as Dr. Zaoutis states, leads to epigenetic intracellular changes, more sensitive synapses, improved blood flow, and even new cells as a result of experience dependent neuroplasticity. For example, stated Dr. Zaoutis, London taxi drivers have thicker white matter in their hippocampus as a result of the effect of learning London city streets, and mindfulness meditators have thicker gray matter in regions that control attention and self-insight.

Key Takeaways:

The lesson for pediatric hospitalists, stated Dr. Zaoutis, is that you can shape your brain for greater joy. “Consciously choose activities,” said Dr. Zaoutis, that counter our evolutionary negativity bias. How is this done?

1. Have a positive experience (you can create one or retrieve a prior one);

2. Enrich it and install it by dwelling on it for at least 15-30 seconds; and

3. Absorb it into your body, which my require somatisizing it – Dr. Zaoutis presses her hand into her chest to aid in this.

Further, spread this to your group by the old medical training technique of “see one, do one, teach one.” See if you can start your signout with the best thing that happened to you in the week. Most importantly, start with observing yourself.

Speaker: Lisa Zaoutis, MD, Pediatric Residency Program Director at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Amid the skyscrapers of the Windy City, Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) 2016 swept into town, bringing with it the denizens of pediatric hospitalist programs across the country. Some 1,150 attendees, comprised of hospitalists, PHM program leaders, and advanced care practitioners, gathered to educate and inspire one another in the the care of hospitalized children.

Dr. Lisa Zaoutis, director of the pediatric residency program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, kicked off the conference with the opening plenary. Initially titled “North Star and Space,” she quickly changed the title to, “Changing Our Minds.” Touching on the disconnect between positive experiences that bring physicians into PHM and negative experiences that often drive behavior, she started with the beginning, the evolution of our brains.

“We are wired toward the negative,” stated Dr. Zaoutis. “We are Teflon for positive experiences and Velcro for negative experiences.” In addition, negative experiences are more likely to be stored in our memories. “It’s easy to park negative experiences.”

Delving deeper into neuroanatomy, Dr. Zaoutis spoke of “amygdala hijack,” where chronic stress inherent to the professional lives of pediatric hospitalists lead to anxiety responses that are faster, more robust, and triggered more easily.

But all is not lost, asserted Dr. Zaoutis, as our brains are more plastic than previously known. The “neural Darwinism,” of our brains, as Dr. Zaoutis states, leads to epigenetic intracellular changes, more sensitive synapses, improved blood flow, and even new cells as a result of experience dependent neuroplasticity. For example, stated Dr. Zaoutis, London taxi drivers have thicker white matter in their hippocampus as a result of the effect of learning London city streets, and mindfulness meditators have thicker gray matter in regions that control attention and self-insight.

Key Takeaways:

The lesson for pediatric hospitalists, stated Dr. Zaoutis, is that you can shape your brain for greater joy. “Consciously choose activities,” said Dr. Zaoutis, that counter our evolutionary negativity bias. How is this done?

1. Have a positive experience (you can create one or retrieve a prior one);

2. Enrich it and install it by dwelling on it for at least 15-30 seconds; and

3. Absorb it into your body, which my require somatisizing it – Dr. Zaoutis presses her hand into her chest to aid in this.

Further, spread this to your group by the old medical training technique of “see one, do one, teach one.” See if you can start your signout with the best thing that happened to you in the week. Most importantly, start with observing yourself.

Speaker: Lisa Zaoutis, MD, Pediatric Residency Program Director at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Amid the skyscrapers of the Windy City, Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) 2016 swept into town, bringing with it the denizens of pediatric hospitalist programs across the country. Some 1,150 attendees, comprised of hospitalists, PHM program leaders, and advanced care practitioners, gathered to educate and inspire one another in the the care of hospitalized children.

Dr. Lisa Zaoutis, director of the pediatric residency program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, kicked off the conference with the opening plenary. Initially titled “North Star and Space,” she quickly changed the title to, “Changing Our Minds.” Touching on the disconnect between positive experiences that bring physicians into PHM and negative experiences that often drive behavior, she started with the beginning, the evolution of our brains.

“We are wired toward the negative,” stated Dr. Zaoutis. “We are Teflon for positive experiences and Velcro for negative experiences.” In addition, negative experiences are more likely to be stored in our memories. “It’s easy to park negative experiences.”

Delving deeper into neuroanatomy, Dr. Zaoutis spoke of “amygdala hijack,” where chronic stress inherent to the professional lives of pediatric hospitalists lead to anxiety responses that are faster, more robust, and triggered more easily.

But all is not lost, asserted Dr. Zaoutis, as our brains are more plastic than previously known. The “neural Darwinism,” of our brains, as Dr. Zaoutis states, leads to epigenetic intracellular changes, more sensitive synapses, improved blood flow, and even new cells as a result of experience dependent neuroplasticity. For example, stated Dr. Zaoutis, London taxi drivers have thicker white matter in their hippocampus as a result of the effect of learning London city streets, and mindfulness meditators have thicker gray matter in regions that control attention and self-insight.

Key Takeaways:

The lesson for pediatric hospitalists, stated Dr. Zaoutis, is that you can shape your brain for greater joy. “Consciously choose activities,” said Dr. Zaoutis, that counter our evolutionary negativity bias. How is this done?

1. Have a positive experience (you can create one or retrieve a prior one);

2. Enrich it and install it by dwelling on it for at least 15-30 seconds; and

3. Absorb it into your body, which my require somatisizing it – Dr. Zaoutis presses her hand into her chest to aid in this.

Further, spread this to your group by the old medical training technique of “see one, do one, teach one.” See if you can start your signout with the best thing that happened to you in the week. Most importantly, start with observing yourself.

VTEP Guidelines Can Be Systematically Implemented in Pediatric Inpatients

Clinical question: Can venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (VTEP) guidelines be systematically implemented in a pediatric inpatient population?

Background: VTEP for hospitalized adult medical patients has been characterized in the literature as being safe and efficacious, although mortality benefits are unclear.1 Systematic risk stratification based on electronic medical records (EMRs) with resultant implementation of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis has been shown to improve appropriate VTEP ordering in the adult inpatient population.2

Although the incidence of VTE is known to be increasing in the pediatric population, systematic VTEP implementation in hospitalized children is not well-described. Prior studies have shown the safety of systematic VTEP implementation through a protocol identifying high-risk pediatric inpatients with resultant initiation of appropriate VTEP. 3,4

Risk stratification in prior studies has taken into consideration risk factors such as altered mobility, presence of a central venous catheter (CVC), spinal cord injury (SCI), major lower-extremity orthopedic surgery, major trauma, active malignancy, acute infection, obesity, estrogen use, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), prior VTE, and family history of VTE.4

Study design: Prospective cohort study using QI methodology.

Setting: A 455-bed, tertiary, freestanding children’s hospital.

Synopsis: After reviewing current literature for VTEP in adults and children and existing institutional pathways for VTEP in adults, traumatic brain injury, and SCI, a multidisciplinary committee formulated VTEP guidelines for 12- to 17-year-old patients. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was considered appropriate in the absence of contraindications and only if CVC and altered mobility were present as risk factors. Using a previously published logistic regression model evaluating VTE risk factors, patients were further categorized as high, moderate, or low risk.

Initial risk-factor categorization was via EMR-based order set, where risk factors were displayed, but subsequently was performed by an integrated tool based on an initial screening form completed by providers upon admission. Logic rules applied by the EMR led to specific VTEP recommendations, which were then selectable by the provider.

Over the first 17 months of EMR tool use, 148 patients on average were admitted each month. VTEP screening rates via the EMR tool increased from 48% in the first month to 81% in the final month. Despite EMR tool usage, VTEP orders did not always correlate with recommendations. Although not a stated objective of the study, none of the screened patients developed a VTE (compared to three cases of VTE in patients between 12 and 17 years of age the year prior).

Bottom line: VTEP guidelines can be systematically implemented via an EMR-based tool in a pediatric inpatient population.

Citation: Mahajerin A, Webber E, Morris J, Taylor K, Saysana M. Development and implementation results of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis guideline in a tertiary care pediatric hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(12):630-636.

References

- Spyropoulos AC, Mahan C. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the medical patient: controversies and perspectives. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):1077-1084.

- Kahn SR, Morrison DR, Cohen JM, et al. Interventions for implementation of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and surgical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008201.

- Takemoto CM, Sohi S, Desai K, et al. Hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in children: incidence and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):332-338.

- Raffini L, Trimarchi T, Beliveau J, Davis D. Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital: a patient-safety and quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1326-1332.

Clinical question: Can venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (VTEP) guidelines be systematically implemented in a pediatric inpatient population?

Background: VTEP for hospitalized adult medical patients has been characterized in the literature as being safe and efficacious, although mortality benefits are unclear.1 Systematic risk stratification based on electronic medical records (EMRs) with resultant implementation of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis has been shown to improve appropriate VTEP ordering in the adult inpatient population.2

Although the incidence of VTE is known to be increasing in the pediatric population, systematic VTEP implementation in hospitalized children is not well-described. Prior studies have shown the safety of systematic VTEP implementation through a protocol identifying high-risk pediatric inpatients with resultant initiation of appropriate VTEP. 3,4

Risk stratification in prior studies has taken into consideration risk factors such as altered mobility, presence of a central venous catheter (CVC), spinal cord injury (SCI), major lower-extremity orthopedic surgery, major trauma, active malignancy, acute infection, obesity, estrogen use, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), prior VTE, and family history of VTE.4

Study design: Prospective cohort study using QI methodology.

Setting: A 455-bed, tertiary, freestanding children’s hospital.

Synopsis: After reviewing current literature for VTEP in adults and children and existing institutional pathways for VTEP in adults, traumatic brain injury, and SCI, a multidisciplinary committee formulated VTEP guidelines for 12- to 17-year-old patients. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was considered appropriate in the absence of contraindications and only if CVC and altered mobility were present as risk factors. Using a previously published logistic regression model evaluating VTE risk factors, patients were further categorized as high, moderate, or low risk.

Initial risk-factor categorization was via EMR-based order set, where risk factors were displayed, but subsequently was performed by an integrated tool based on an initial screening form completed by providers upon admission. Logic rules applied by the EMR led to specific VTEP recommendations, which were then selectable by the provider.

Over the first 17 months of EMR tool use, 148 patients on average were admitted each month. VTEP screening rates via the EMR tool increased from 48% in the first month to 81% in the final month. Despite EMR tool usage, VTEP orders did not always correlate with recommendations. Although not a stated objective of the study, none of the screened patients developed a VTE (compared to three cases of VTE in patients between 12 and 17 years of age the year prior).

Bottom line: VTEP guidelines can be systematically implemented via an EMR-based tool in a pediatric inpatient population.

Citation: Mahajerin A, Webber E, Morris J, Taylor K, Saysana M. Development and implementation results of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis guideline in a tertiary care pediatric hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(12):630-636.

References

- Spyropoulos AC, Mahan C. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the medical patient: controversies and perspectives. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):1077-1084.

- Kahn SR, Morrison DR, Cohen JM, et al. Interventions for implementation of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and surgical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008201.

- Takemoto CM, Sohi S, Desai K, et al. Hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in children: incidence and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):332-338.

- Raffini L, Trimarchi T, Beliveau J, Davis D. Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital: a patient-safety and quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1326-1332.

Clinical question: Can venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (VTEP) guidelines be systematically implemented in a pediatric inpatient population?

Background: VTEP for hospitalized adult medical patients has been characterized in the literature as being safe and efficacious, although mortality benefits are unclear.1 Systematic risk stratification based on electronic medical records (EMRs) with resultant implementation of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis has been shown to improve appropriate VTEP ordering in the adult inpatient population.2

Although the incidence of VTE is known to be increasing in the pediatric population, systematic VTEP implementation in hospitalized children is not well-described. Prior studies have shown the safety of systematic VTEP implementation through a protocol identifying high-risk pediatric inpatients with resultant initiation of appropriate VTEP. 3,4

Risk stratification in prior studies has taken into consideration risk factors such as altered mobility, presence of a central venous catheter (CVC), spinal cord injury (SCI), major lower-extremity orthopedic surgery, major trauma, active malignancy, acute infection, obesity, estrogen use, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), prior VTE, and family history of VTE.4

Study design: Prospective cohort study using QI methodology.

Setting: A 455-bed, tertiary, freestanding children’s hospital.

Synopsis: After reviewing current literature for VTEP in adults and children and existing institutional pathways for VTEP in adults, traumatic brain injury, and SCI, a multidisciplinary committee formulated VTEP guidelines for 12- to 17-year-old patients. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was considered appropriate in the absence of contraindications and only if CVC and altered mobility were present as risk factors. Using a previously published logistic regression model evaluating VTE risk factors, patients were further categorized as high, moderate, or low risk.

Initial risk-factor categorization was via EMR-based order set, where risk factors were displayed, but subsequently was performed by an integrated tool based on an initial screening form completed by providers upon admission. Logic rules applied by the EMR led to specific VTEP recommendations, which were then selectable by the provider.

Over the first 17 months of EMR tool use, 148 patients on average were admitted each month. VTEP screening rates via the EMR tool increased from 48% in the first month to 81% in the final month. Despite EMR tool usage, VTEP orders did not always correlate with recommendations. Although not a stated objective of the study, none of the screened patients developed a VTE (compared to three cases of VTE in patients between 12 and 17 years of age the year prior).

Bottom line: VTEP guidelines can be systematically implemented via an EMR-based tool in a pediatric inpatient population.

Citation: Mahajerin A, Webber E, Morris J, Taylor K, Saysana M. Development and implementation results of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis guideline in a tertiary care pediatric hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(12):630-636.

References

- Spyropoulos AC, Mahan C. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the medical patient: controversies and perspectives. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):1077-1084.

- Kahn SR, Morrison DR, Cohen JM, et al. Interventions for implementation of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and surgical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008201.

- Takemoto CM, Sohi S, Desai K, et al. Hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in children: incidence and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):332-338.

- Raffini L, Trimarchi T, Beliveau J, Davis D. Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital: a patient-safety and quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1326-1332.

QUIZ: When Should You Suspect Kawasaki Disease as the Cause of Fever in an Infant?

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology that occurs in children. Because there is no specific diagnostic test or pathognomonic clinical feature, clinical diagnostic criteria have been established to guide physicians. When a patient presents with a history, examination, and laboratory findings consistent with KD without meeting the typical diagnostic standard, incomplete KD should be considered.

[WpProQuiz 4]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 4]

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology that occurs in children. Because there is no specific diagnostic test or pathognomonic clinical feature, clinical diagnostic criteria have been established to guide physicians. When a patient presents with a history, examination, and laboratory findings consistent with KD without meeting the typical diagnostic standard, incomplete KD should be considered.

[WpProQuiz 4]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 4]

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology that occurs in children. Because there is no specific diagnostic test or pathognomonic clinical feature, clinical diagnostic criteria have been established to guide physicians. When a patient presents with a history, examination, and laboratory findings consistent with KD without meeting the typical diagnostic standard, incomplete KD should be considered.

[WpProQuiz 4]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 4]

Nebulized Hypertonic Saline Does Not Improve Outcomes for Non-ICU Infants with Acute Bronchiolitis

Clinical question: Does the use of nebulized 3% hypertonic saline shorten length of stay (LOS) in infants hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis?

Background: Acute bronchiolitis is a disease primarily of infants and young children, triggered by a viral infection that leads to variable inflammation, edema, and inspissated mucus in the lower airways. Although bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization in children under the age of two, few interventions have been shown to improve patient-level outcomes.

Hypertonic saline (generally 3%) has been one of the few interventions that has improved outcomes in some studies, leading the most recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guideline (CPG) to state that nebulized hypertonic saline may be considered for infants and children hospitalized for bronchiolitis. The studies cited in this CPG statement were heterogeneous, with many of them performed in Europe, where the LOS for bronchiolitis is generally longer than in the U.S. In addition, most of the studies administered hypertonic saline (HS) with a bronchodilator, confounding the outcomes with an intervention not recommended in the most recent bronchiolitis CPG.

Study design: Prospective, randomized controlled, double-blinded, parallel-group study.

Setting: Urban, tertiary-care, 136-bed children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Infants 4 points received a bronchodilator and were withdrawn from the study.

Of the 227 patients enrolled after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 113 were randomized to receive HS and 114 to NS. Twenty patients in the HS group and 17 in the NS group discontinued intervention due to ICU transfer, provider choice to use albuterol, parental request, or protocol deviation, but patients were analyzed by intention-to-treat (ITT) assignments. No significant difference in LOS between the HS and NS groups was found, either by the traditional definition or the treatment-to-discharge order definition. No significant differences were found in secondary outcomes between the two groups, including readmission rates or clinical worsening. In addition, pre- to post-treatment RDAI score changes were not significantly different for HS versus NS.

Bottom line: Treating infants

Citation: Silver AH, Esteban-Cruciani N, Azzarone G, et al. 3% hypertonic saline versus normal saline in inpatient bronchiolitis: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1036-1043. TH

Clinical question: Does the use of nebulized 3% hypertonic saline shorten length of stay (LOS) in infants hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis?

Background: Acute bronchiolitis is a disease primarily of infants and young children, triggered by a viral infection that leads to variable inflammation, edema, and inspissated mucus in the lower airways. Although bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization in children under the age of two, few interventions have been shown to improve patient-level outcomes.

Hypertonic saline (generally 3%) has been one of the few interventions that has improved outcomes in some studies, leading the most recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guideline (CPG) to state that nebulized hypertonic saline may be considered for infants and children hospitalized for bronchiolitis. The studies cited in this CPG statement were heterogeneous, with many of them performed in Europe, where the LOS for bronchiolitis is generally longer than in the U.S. In addition, most of the studies administered hypertonic saline (HS) with a bronchodilator, confounding the outcomes with an intervention not recommended in the most recent bronchiolitis CPG.

Study design: Prospective, randomized controlled, double-blinded, parallel-group study.

Setting: Urban, tertiary-care, 136-bed children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Infants 4 points received a bronchodilator and were withdrawn from the study.

Of the 227 patients enrolled after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 113 were randomized to receive HS and 114 to NS. Twenty patients in the HS group and 17 in the NS group discontinued intervention due to ICU transfer, provider choice to use albuterol, parental request, or protocol deviation, but patients were analyzed by intention-to-treat (ITT) assignments. No significant difference in LOS between the HS and NS groups was found, either by the traditional definition or the treatment-to-discharge order definition. No significant differences were found in secondary outcomes between the two groups, including readmission rates or clinical worsening. In addition, pre- to post-treatment RDAI score changes were not significantly different for HS versus NS.

Bottom line: Treating infants

Citation: Silver AH, Esteban-Cruciani N, Azzarone G, et al. 3% hypertonic saline versus normal saline in inpatient bronchiolitis: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1036-1043. TH

Clinical question: Does the use of nebulized 3% hypertonic saline shorten length of stay (LOS) in infants hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis?

Background: Acute bronchiolitis is a disease primarily of infants and young children, triggered by a viral infection that leads to variable inflammation, edema, and inspissated mucus in the lower airways. Although bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization in children under the age of two, few interventions have been shown to improve patient-level outcomes.

Hypertonic saline (generally 3%) has been one of the few interventions that has improved outcomes in some studies, leading the most recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guideline (CPG) to state that nebulized hypertonic saline may be considered for infants and children hospitalized for bronchiolitis. The studies cited in this CPG statement were heterogeneous, with many of them performed in Europe, where the LOS for bronchiolitis is generally longer than in the U.S. In addition, most of the studies administered hypertonic saline (HS) with a bronchodilator, confounding the outcomes with an intervention not recommended in the most recent bronchiolitis CPG.

Study design: Prospective, randomized controlled, double-blinded, parallel-group study.

Setting: Urban, tertiary-care, 136-bed children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Infants 4 points received a bronchodilator and were withdrawn from the study.

Of the 227 patients enrolled after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 113 were randomized to receive HS and 114 to NS. Twenty patients in the HS group and 17 in the NS group discontinued intervention due to ICU transfer, provider choice to use albuterol, parental request, or protocol deviation, but patients were analyzed by intention-to-treat (ITT) assignments. No significant difference in LOS between the HS and NS groups was found, either by the traditional definition or the treatment-to-discharge order definition. No significant differences were found in secondary outcomes between the two groups, including readmission rates or clinical worsening. In addition, pre- to post-treatment RDAI score changes were not significantly different for HS versus NS.

Bottom line: Treating infants

Citation: Silver AH, Esteban-Cruciani N, Azzarone G, et al. 3% hypertonic saline versus normal saline in inpatient bronchiolitis: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1036-1043. TH

Parental Perceptions of Nighttime Communication Are Strong Predictors of Patient Experience

Clinical question: How does parental perception of overnight pediatric inpatient care affect the overall patient experience?

Background: Restrictions on resident duty hours have become progressively more stringent as attention to the effects of resident fatigue on patient safety has increased. In 2011, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) limited total weekly duty hours to 80 and reduced shifts for junior trainees to a maximum of 16 hours. As a result, a majority of teaching hospitals have instituted “night float,” or night team models, for overnight coverage of pediatric inpatients. The rapid adoption of night float inpatient coverage models has raised concerns about training residents in a structure that may not foster patient ownership and may promote shift worker mentality. Although communication between healthcare providers and patients/caregivers is known to be a key driver of patient satisfaction, little is known about the quality of communication overnight in the era of night float teams.

Study design: Prospective cohort study utilizing survey methodology.

Setting: Two general pediatric units at a 395-bed, urban, freestanding children’s teaching hospital.

Synopsis: A randomly selected subset of children (0-17 years) with English-speaking parents/caregivers admitted to two general pediatric units was studied over an 18-month period. Both general pediatric and subspecialty service patients, including adolescent, immunology, hematology, and rheumatology, were included. Researchers administered written surveys on weekday (Monday-Thursday) evenings prior to discharge, and surveys were collected either later that evening or in the morning. The surveys included 29 questions that used a five-point Likert scale to assess communication and experience.

These questions covered the following constructs:

- Parent understanding of the medical plan;

- Parent communication and experience with nighttime doctors;

- Parent communication and experience with nighttime nurses;

- Parent perceptions of nighttime interactions between doctors and nurses; and

- Parent overall experience of care during hospitalization.

An open question addressing whether parents had anything else to share about communication during the hospitalization was included. The primary outcome measure was the so-called “top-box” rating of overall experience of care during the hospitalization (from construct five). This outcome was dichotomous based on whether the parent had given the highest rating or not for all five questions in that construct (either “excellent” or “strongly agree”).

A top-box rating of overall experience of care was found to be associated with high mean construct scores regarding communication and experience with doctors (4.85) and nurses (4.87). Top-box overall experience ratings were also associated with top ratings for coordination between daytime and nighttime nurses and for teamwork between nighttime doctors and nurses. Multivariable analysis showed that parents’ rating of direct communications with doctors and nurses and perceived teamwork and communication between doctors and nurses were significant predictors of top-box overall experience.

Bottom line: Parents’ perceptions of direct communications with nighttime doctors and nurses and their perceived teamwork and communication were strong predictors of overall experience of care during pediatric hospitalization.

Citation: Khan A, Rogers JE, Melvin P, et al. Physician and nurse nighttime communication and parents’ hospital experience. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1249-1258.

Clinical question: How does parental perception of overnight pediatric inpatient care affect the overall patient experience?

Background: Restrictions on resident duty hours have become progressively more stringent as attention to the effects of resident fatigue on patient safety has increased. In 2011, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) limited total weekly duty hours to 80 and reduced shifts for junior trainees to a maximum of 16 hours. As a result, a majority of teaching hospitals have instituted “night float,” or night team models, for overnight coverage of pediatric inpatients. The rapid adoption of night float inpatient coverage models has raised concerns about training residents in a structure that may not foster patient ownership and may promote shift worker mentality. Although communication between healthcare providers and patients/caregivers is known to be a key driver of patient satisfaction, little is known about the quality of communication overnight in the era of night float teams.

Study design: Prospective cohort study utilizing survey methodology.

Setting: Two general pediatric units at a 395-bed, urban, freestanding children’s teaching hospital.

Synopsis: A randomly selected subset of children (0-17 years) with English-speaking parents/caregivers admitted to two general pediatric units was studied over an 18-month period. Both general pediatric and subspecialty service patients, including adolescent, immunology, hematology, and rheumatology, were included. Researchers administered written surveys on weekday (Monday-Thursday) evenings prior to discharge, and surveys were collected either later that evening or in the morning. The surveys included 29 questions that used a five-point Likert scale to assess communication and experience.

These questions covered the following constructs:

- Parent understanding of the medical plan;

- Parent communication and experience with nighttime doctors;

- Parent communication and experience with nighttime nurses;

- Parent perceptions of nighttime interactions between doctors and nurses; and

- Parent overall experience of care during hospitalization.

An open question addressing whether parents had anything else to share about communication during the hospitalization was included. The primary outcome measure was the so-called “top-box” rating of overall experience of care during the hospitalization (from construct five). This outcome was dichotomous based on whether the parent had given the highest rating or not for all five questions in that construct (either “excellent” or “strongly agree”).

A top-box rating of overall experience of care was found to be associated with high mean construct scores regarding communication and experience with doctors (4.85) and nurses (4.87). Top-box overall experience ratings were also associated with top ratings for coordination between daytime and nighttime nurses and for teamwork between nighttime doctors and nurses. Multivariable analysis showed that parents’ rating of direct communications with doctors and nurses and perceived teamwork and communication between doctors and nurses were significant predictors of top-box overall experience.

Bottom line: Parents’ perceptions of direct communications with nighttime doctors and nurses and their perceived teamwork and communication were strong predictors of overall experience of care during pediatric hospitalization.

Citation: Khan A, Rogers JE, Melvin P, et al. Physician and nurse nighttime communication and parents’ hospital experience. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1249-1258.

Clinical question: How does parental perception of overnight pediatric inpatient care affect the overall patient experience?

Background: Restrictions on resident duty hours have become progressively more stringent as attention to the effects of resident fatigue on patient safety has increased. In 2011, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) limited total weekly duty hours to 80 and reduced shifts for junior trainees to a maximum of 16 hours. As a result, a majority of teaching hospitals have instituted “night float,” or night team models, for overnight coverage of pediatric inpatients. The rapid adoption of night float inpatient coverage models has raised concerns about training residents in a structure that may not foster patient ownership and may promote shift worker mentality. Although communication between healthcare providers and patients/caregivers is known to be a key driver of patient satisfaction, little is known about the quality of communication overnight in the era of night float teams.

Study design: Prospective cohort study utilizing survey methodology.

Setting: Two general pediatric units at a 395-bed, urban, freestanding children’s teaching hospital.

Synopsis: A randomly selected subset of children (0-17 years) with English-speaking parents/caregivers admitted to two general pediatric units was studied over an 18-month period. Both general pediatric and subspecialty service patients, including adolescent, immunology, hematology, and rheumatology, were included. Researchers administered written surveys on weekday (Monday-Thursday) evenings prior to discharge, and surveys were collected either later that evening or in the morning. The surveys included 29 questions that used a five-point Likert scale to assess communication and experience.

These questions covered the following constructs:

- Parent understanding of the medical plan;

- Parent communication and experience with nighttime doctors;

- Parent communication and experience with nighttime nurses;

- Parent perceptions of nighttime interactions between doctors and nurses; and

- Parent overall experience of care during hospitalization.

An open question addressing whether parents had anything else to share about communication during the hospitalization was included. The primary outcome measure was the so-called “top-box” rating of overall experience of care during the hospitalization (from construct five). This outcome was dichotomous based on whether the parent had given the highest rating or not for all five questions in that construct (either “excellent” or “strongly agree”).

A top-box rating of overall experience of care was found to be associated with high mean construct scores regarding communication and experience with doctors (4.85) and nurses (4.87). Top-box overall experience ratings were also associated with top ratings for coordination between daytime and nighttime nurses and for teamwork between nighttime doctors and nurses. Multivariable analysis showed that parents’ rating of direct communications with doctors and nurses and perceived teamwork and communication between doctors and nurses were significant predictors of top-box overall experience.

Bottom line: Parents’ perceptions of direct communications with nighttime doctors and nurses and their perceived teamwork and communication were strong predictors of overall experience of care during pediatric hospitalization.

Citation: Khan A, Rogers JE, Melvin P, et al. Physician and nurse nighttime communication and parents’ hospital experience. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1249-1258.

The Lone Hospitalist in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan

The lives of academic hospitalists are fraught with pitfalls and perils that can lead the unsuspecting far afield of their original intentions. It was in the murky depths of such professional perplexity that I recently found myself, lying in bed and attempting repose in vain. Thoughts of living a life underpaid, underresourced, and overworked buzzed in my psyche. After some tossing and turning, I slipped out of bed and into my home office and began watching cooking videos, which tend to have a calming effect on me, on The New York Times website.

The title of the first video in the queue, however, caught my eye: “The Worst Atrocity You’ve Never Heard Of,” by Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. To be honest, I try to avoid reading about the multitude of human disasters in Africa—the sheer numbers, size, scope, and hopelessness of human suffering make reading about them an exercise in despair and futility. Yet I clicked the link and began to see and hear about the plight of the people living in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan.

The Nuba Mountains, in the southern region of Sudan, lie north of a new border recently established between Sudan and the new country of South Sudan, for whose independence the Sudan People’s Liberation Army rebels fought in a war that ended in 2005. The rebels, however, continue to fight the Sudanese government in the Nuba Mountain region, with the Sudanese Air Force escalating a bombing campaign against the rebels in 2011. Since 2012, 3,740 bombs have been dropped on civilian targets in the Nuba Mountain region, resulting in countless deaths, shrapnel injuries, and burns.

In the midst of this mayhem, few medical providers have stood their ground. On January 20, a fighter jet dropped a cluster of 13 bombs into a hospital operated by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the Nuba Mountains village of Frandala—the second time the hospital had been bombed. MSF suspended its operations in Sudan soon thereafter. That left exactly one hospital operating in an area of the Nuba Mountains the size of Switzerland, with a population of 750,000. And, since 2008, there has been only one physician, Tom Catena, MD, at Mother of Mercy Hospital.

Dr. Catena, who received his medical degree from Duke University after being an all-Ivy League nose guard and Rhodes Scholar candidate at Brown, came to Mother of Mercy Hospital after missionary medicine work elsewhere in Africa and Latin America. Since his arrival at the 435-bed hospital, he has been the only physician there other than the occasional visitor. He is on call 24-7 and leaves only rarely. The hospital runs off the electrical grid, has no running water, subsists on scarce medical supplies, and has nary an X-ray machine to aid in diagnosing more trauma in one year than an average ED physician would see in an entire career. Trained in family medicine, he performs more than 1,000 operations yearly on patients suffering from the most egregious trauma and burns imaginable, with only the most basic support staff.

“He is Jesus Christ,” asserted a local Muslim chief in The New York Times video, with any difference in religious background—Dr. Catena is a devout Catholic—fading into irrelevance in the face of such heroic care. From repairing orthopedic injuries, delivering babies, and treating horrific trauma and burns, to handling measles and malaria outbreaks, Dr. Catena ministers to the ill and dying without regard to religion or reimbursement.

And, yet, why? Why would Dr. Catena forgo a comfortable life anywhere in the United States, give up the possibility of practicing in any number of lucrative professional settings (based on the diverse skill set he displays in the video), to earn $350 monthly, with no retirement plan, no disability, and no health insurance? As I watched the video, any concern I had regarding my own future earnings and career evaporated, at least momentarily, in the glow of Dr. Catena’s selfless devotion to his patients. One could understand volunteering in this fashion for a month, maybe a year, but seven years? What could keep him going?

I later referred to an article written by Pat Cawley, MD, and others last year and published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, outlining the characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group, because, in effect, Dr. Catena is a one-man HMG—a solo practice if you will. It is tempting to ascribe his ability to persevere and even thrive in the most inhospitable work environment possible to religious fervor alone. But although he is clearly a devout Catholic, his laconic, “aw shucks” manner suggests the demeanor of an old-time country doctor more than a zealot. As I reread Dr. Cawley’s article, I found that, not surprisingly, Dr. Catena’s “group” fails on many counts. A small sampling:

- 1.2: The HMG has an active leadership development plan that is supported with appropriate budget, time, and other resources. Underresourced seems an understatement here.

- 4.5: The HMG is supported by appropriate practice management information technology, clinical information technology, and data analytics. The last HMG on earth without an EMR?

- 10.1: Hospitalist compensation is market competitive. And the market is…?

On other characteristics, however, Dr. Catena does surprisingly well:

- 3.2: All HMG team members (including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and ancillary staff) have clearly defined, meaningful roles. Dr. Catena spends extensive time training undereducated but well-meaning local volunteers in providing ancillary services.

- 5.4: The HMG periodically solicits satisfaction feedback from key stakeholder groups, which is shared with all hospitalists and used to develop and implement improvement plans. The local population is so thankful for his care, they have tried to introduce him to local eligible women in the hope that he will marry and never leave.

- 9.1: The HMG’s hospitalists provide care that respects and responds to patient and family preferences, needs, and values. Dr. Catena’s humility and respect for the Nubian people and culture is what keeps him at Mother of Mercy, despite 11 bombings, grueling work, and negligible pay.

But the one characteristic missing from Dr. Cawley’s list is likely what keeps Dr. Catena in the Nuba Mountains: He practices at the limit of his skill set on a daily basis and spends the majority of his time in doing what he loves most, patient care (when he is not in his self-dug bomb shelter hole), not being chained behind a computer.

It is the failure of Dr. Catena’s group on one of the last characteristics, however, that likely is its greatest:

- 10.3: The HMG’s hospitalists are actively engaged in sourcing and recruiting new members. Somehow, I think finding someone to take Dr. Catena’s place will be difficult.

The lives of academic hospitalists are fraught with pitfalls and perils that can lead the unsuspecting far afield of their original intentions. It was in the murky depths of such professional perplexity that I recently found myself, lying in bed and attempting repose in vain. Thoughts of living a life underpaid, underresourced, and overworked buzzed in my psyche. After some tossing and turning, I slipped out of bed and into my home office and began watching cooking videos, which tend to have a calming effect on me, on The New York Times website.

The title of the first video in the queue, however, caught my eye: “The Worst Atrocity You’ve Never Heard Of,” by Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. To be honest, I try to avoid reading about the multitude of human disasters in Africa—the sheer numbers, size, scope, and hopelessness of human suffering make reading about them an exercise in despair and futility. Yet I clicked the link and began to see and hear about the plight of the people living in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan.

The Nuba Mountains, in the southern region of Sudan, lie north of a new border recently established between Sudan and the new country of South Sudan, for whose independence the Sudan People’s Liberation Army rebels fought in a war that ended in 2005. The rebels, however, continue to fight the Sudanese government in the Nuba Mountain region, with the Sudanese Air Force escalating a bombing campaign against the rebels in 2011. Since 2012, 3,740 bombs have been dropped on civilian targets in the Nuba Mountain region, resulting in countless deaths, shrapnel injuries, and burns.

In the midst of this mayhem, few medical providers have stood their ground. On January 20, a fighter jet dropped a cluster of 13 bombs into a hospital operated by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the Nuba Mountains village of Frandala—the second time the hospital had been bombed. MSF suspended its operations in Sudan soon thereafter. That left exactly one hospital operating in an area of the Nuba Mountains the size of Switzerland, with a population of 750,000. And, since 2008, there has been only one physician, Tom Catena, MD, at Mother of Mercy Hospital.

Dr. Catena, who received his medical degree from Duke University after being an all-Ivy League nose guard and Rhodes Scholar candidate at Brown, came to Mother of Mercy Hospital after missionary medicine work elsewhere in Africa and Latin America. Since his arrival at the 435-bed hospital, he has been the only physician there other than the occasional visitor. He is on call 24-7 and leaves only rarely. The hospital runs off the electrical grid, has no running water, subsists on scarce medical supplies, and has nary an X-ray machine to aid in diagnosing more trauma in one year than an average ED physician would see in an entire career. Trained in family medicine, he performs more than 1,000 operations yearly on patients suffering from the most egregious trauma and burns imaginable, with only the most basic support staff.

“He is Jesus Christ,” asserted a local Muslim chief in The New York Times video, with any difference in religious background—Dr. Catena is a devout Catholic—fading into irrelevance in the face of such heroic care. From repairing orthopedic injuries, delivering babies, and treating horrific trauma and burns, to handling measles and malaria outbreaks, Dr. Catena ministers to the ill and dying without regard to religion or reimbursement.

And, yet, why? Why would Dr. Catena forgo a comfortable life anywhere in the United States, give up the possibility of practicing in any number of lucrative professional settings (based on the diverse skill set he displays in the video), to earn $350 monthly, with no retirement plan, no disability, and no health insurance? As I watched the video, any concern I had regarding my own future earnings and career evaporated, at least momentarily, in the glow of Dr. Catena’s selfless devotion to his patients. One could understand volunteering in this fashion for a month, maybe a year, but seven years? What could keep him going?

I later referred to an article written by Pat Cawley, MD, and others last year and published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, outlining the characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group, because, in effect, Dr. Catena is a one-man HMG—a solo practice if you will. It is tempting to ascribe his ability to persevere and even thrive in the most inhospitable work environment possible to religious fervor alone. But although he is clearly a devout Catholic, his laconic, “aw shucks” manner suggests the demeanor of an old-time country doctor more than a zealot. As I reread Dr. Cawley’s article, I found that, not surprisingly, Dr. Catena’s “group” fails on many counts. A small sampling:

- 1.2: The HMG has an active leadership development plan that is supported with appropriate budget, time, and other resources. Underresourced seems an understatement here.

- 4.5: The HMG is supported by appropriate practice management information technology, clinical information technology, and data analytics. The last HMG on earth without an EMR?

- 10.1: Hospitalist compensation is market competitive. And the market is…?

On other characteristics, however, Dr. Catena does surprisingly well:

- 3.2: All HMG team members (including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and ancillary staff) have clearly defined, meaningful roles. Dr. Catena spends extensive time training undereducated but well-meaning local volunteers in providing ancillary services.

- 5.4: The HMG periodically solicits satisfaction feedback from key stakeholder groups, which is shared with all hospitalists and used to develop and implement improvement plans. The local population is so thankful for his care, they have tried to introduce him to local eligible women in the hope that he will marry and never leave.

- 9.1: The HMG’s hospitalists provide care that respects and responds to patient and family preferences, needs, and values. Dr. Catena’s humility and respect for the Nubian people and culture is what keeps him at Mother of Mercy, despite 11 bombings, grueling work, and negligible pay.

But the one characteristic missing from Dr. Cawley’s list is likely what keeps Dr. Catena in the Nuba Mountains: He practices at the limit of his skill set on a daily basis and spends the majority of his time in doing what he loves most, patient care (when he is not in his self-dug bomb shelter hole), not being chained behind a computer.

It is the failure of Dr. Catena’s group on one of the last characteristics, however, that likely is its greatest:

- 10.3: The HMG’s hospitalists are actively engaged in sourcing and recruiting new members. Somehow, I think finding someone to take Dr. Catena’s place will be difficult.

The lives of academic hospitalists are fraught with pitfalls and perils that can lead the unsuspecting far afield of their original intentions. It was in the murky depths of such professional perplexity that I recently found myself, lying in bed and attempting repose in vain. Thoughts of living a life underpaid, underresourced, and overworked buzzed in my psyche. After some tossing and turning, I slipped out of bed and into my home office and began watching cooking videos, which tend to have a calming effect on me, on The New York Times website.

The title of the first video in the queue, however, caught my eye: “The Worst Atrocity You’ve Never Heard Of,” by Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. To be honest, I try to avoid reading about the multitude of human disasters in Africa—the sheer numbers, size, scope, and hopelessness of human suffering make reading about them an exercise in despair and futility. Yet I clicked the link and began to see and hear about the plight of the people living in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan.

The Nuba Mountains, in the southern region of Sudan, lie north of a new border recently established between Sudan and the new country of South Sudan, for whose independence the Sudan People’s Liberation Army rebels fought in a war that ended in 2005. The rebels, however, continue to fight the Sudanese government in the Nuba Mountain region, with the Sudanese Air Force escalating a bombing campaign against the rebels in 2011. Since 2012, 3,740 bombs have been dropped on civilian targets in the Nuba Mountain region, resulting in countless deaths, shrapnel injuries, and burns.

In the midst of this mayhem, few medical providers have stood their ground. On January 20, a fighter jet dropped a cluster of 13 bombs into a hospital operated by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the Nuba Mountains village of Frandala—the second time the hospital had been bombed. MSF suspended its operations in Sudan soon thereafter. That left exactly one hospital operating in an area of the Nuba Mountains the size of Switzerland, with a population of 750,000. And, since 2008, there has been only one physician, Tom Catena, MD, at Mother of Mercy Hospital.

Dr. Catena, who received his medical degree from Duke University after being an all-Ivy League nose guard and Rhodes Scholar candidate at Brown, came to Mother of Mercy Hospital after missionary medicine work elsewhere in Africa and Latin America. Since his arrival at the 435-bed hospital, he has been the only physician there other than the occasional visitor. He is on call 24-7 and leaves only rarely. The hospital runs off the electrical grid, has no running water, subsists on scarce medical supplies, and has nary an X-ray machine to aid in diagnosing more trauma in one year than an average ED physician would see in an entire career. Trained in family medicine, he performs more than 1,000 operations yearly on patients suffering from the most egregious trauma and burns imaginable, with only the most basic support staff.

“He is Jesus Christ,” asserted a local Muslim chief in The New York Times video, with any difference in religious background—Dr. Catena is a devout Catholic—fading into irrelevance in the face of such heroic care. From repairing orthopedic injuries, delivering babies, and treating horrific trauma and burns, to handling measles and malaria outbreaks, Dr. Catena ministers to the ill and dying without regard to religion or reimbursement.

And, yet, why? Why would Dr. Catena forgo a comfortable life anywhere in the United States, give up the possibility of practicing in any number of lucrative professional settings (based on the diverse skill set he displays in the video), to earn $350 monthly, with no retirement plan, no disability, and no health insurance? As I watched the video, any concern I had regarding my own future earnings and career evaporated, at least momentarily, in the glow of Dr. Catena’s selfless devotion to his patients. One could understand volunteering in this fashion for a month, maybe a year, but seven years? What could keep him going?

I later referred to an article written by Pat Cawley, MD, and others last year and published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, outlining the characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group, because, in effect, Dr. Catena is a one-man HMG—a solo practice if you will. It is tempting to ascribe his ability to persevere and even thrive in the most inhospitable work environment possible to religious fervor alone. But although he is clearly a devout Catholic, his laconic, “aw shucks” manner suggests the demeanor of an old-time country doctor more than a zealot. As I reread Dr. Cawley’s article, I found that, not surprisingly, Dr. Catena’s “group” fails on many counts. A small sampling:

- 1.2: The HMG has an active leadership development plan that is supported with appropriate budget, time, and other resources. Underresourced seems an understatement here.

- 4.5: The HMG is supported by appropriate practice management information technology, clinical information technology, and data analytics. The last HMG on earth without an EMR?

- 10.1: Hospitalist compensation is market competitive. And the market is…?

On other characteristics, however, Dr. Catena does surprisingly well:

- 3.2: All HMG team members (including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and ancillary staff) have clearly defined, meaningful roles. Dr. Catena spends extensive time training undereducated but well-meaning local volunteers in providing ancillary services.

- 5.4: The HMG periodically solicits satisfaction feedback from key stakeholder groups, which is shared with all hospitalists and used to develop and implement improvement plans. The local population is so thankful for his care, they have tried to introduce him to local eligible women in the hope that he will marry and never leave.

- 9.1: The HMG’s hospitalists provide care that respects and responds to patient and family preferences, needs, and values. Dr. Catena’s humility and respect for the Nubian people and culture is what keeps him at Mother of Mercy, despite 11 bombings, grueling work, and negligible pay.

But the one characteristic missing from Dr. Cawley’s list is likely what keeps Dr. Catena in the Nuba Mountains: He practices at the limit of his skill set on a daily basis and spends the majority of his time in doing what he loves most, patient care (when he is not in his self-dug bomb shelter hole), not being chained behind a computer.

It is the failure of Dr. Catena’s group on one of the last characteristics, however, that likely is its greatest:

- 10.3: The HMG’s hospitalists are actively engaged in sourcing and recruiting new members. Somehow, I think finding someone to take Dr. Catena’s place will be difficult.

Standard Discharge Communication Process Improves Verbal Handoffs between Hospitalists, PCPs

Clinical question: Can a standardized discharge communication process, coupled with an electronic health record (EHR) system, improve the proportion of completed verbal handoffs from in-hospital physicians to PCPs within 24 hours of patient discharge?

Background: Discharge from the hospital setting is known to be a transition of care fraught with patient safety risks, with more than half of discharged patients experiencing at least one error.1 Previous studies identified core elements that pediatric hospitalists and PCPs consider essential in discharge communication, which included:

- Pending laboratory or test results;

- Follow-up appointments;

- Discharge medications;

- Admission and discharge diagnoses;

- Dates of admission and discharge; and

- Suggested management plan.2

Rates of transmission and receipt of information have been found to be suboptimal after hospital discharge, and PCPs have been found to be less satisfied than hospitalists with communication.2,3 Additionally, PCPs and hospitalists have been found to have incongruent views on who should be responsible for pending labs, adverse events, or status changes, differences which can have safety implications.3 PCPs who refer to general hospitals have been found to report superior completeness of discharge communication compared to freestanding children’s hospitals, where resident physicians are generally responsible for discharge summary completion.4 Standardizing and promoting a process of verbal handoff after hospital discharge may address some of these safety concerns, although a relationship has not been established between aspects of discharge communication and associated adverse clinical outcomes.5

Study design: Quality improvement study using improvement science methods and run charts.

Setting: An urban, 598-bed, freestanding children’s hospital.

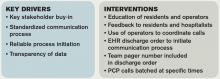

Synopsis: A 24/7 telephone operator service had been established at the investigators’ institution that was designed to facilitate communication between providers inside and outside the institution. At baseline, only 52% of hospital medicine (HM) provider discharges had a record of a discharge day call initiated to the PCP. A project team consisting of hospitalists, a chief resident, operator service administrators, and IT analysts identified system issues that led to unsuccessful communication, which facilitated identification of key drivers of improving communication and associated interventions (see Table 1).

Discharging physicians, who were usually residents, were instructed to call the operator at the time of discharge. Operators would page the PCP, and PCPs were expected to return the page within 20 minutes. Discharging physicians were expected to return the call to the operator within two to four minutes. The EHR generated a message to the operator whenever a discharge order was placed for an HM patient, leading the operator to page the discharging physician to initiate the call.

Adaptations after project initiation included:

- Reassigning primary responsibility for discharge phone calls to the daily on-call resident, if the discharging physician was not available.

- Establishing a non-changing pager number on the automated discharge notification that would always reach the appropriate team member.

- Batching discharge phone calls at times of increased resident availability to minimize hold times for PCPs and work interruptions for discharging physicians.

Weekly failure data was generated and reviewed by the improvement team, and a call record was linked to the patient’s medical record. Team-specific and overall results for HM teams were posted weekly on a run-chart. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of completed calls between PCP and HM physician within 24 hours of discharge.

Over the approximately 32-month study period, the percentage of calls initiated improved from 50% to 97% after four interventions. After one year, data was collected to assess percentage of calls completed, a number that rose from 80% in the first eight weeks to a median of 93%, which was sustained for 18 months.

Bottom line: Utilizing improvement methods and reliability science, a process of improving verbal handoffs between hospital-based physicians and PCPs within 24 hours after discharge led to a sustained improvement, to above 90%, in successful verbal handoffs.

Citation: Mussman GM, Vossmeyer MT, Brady PW, Warrick DM, Simmons JM, White CM. Improving the reliability of verbal communication between primary care physicians and pediatric hospitalists at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print May 29, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2392.

Clinical Shorts

MAJORITY OF NONOBSTRUCTING ASYMPTOMATIC RENAL STONES REMAIN ASYMPTOMATIC OVER TIME

Retrospective trial of active surveillance of asymptomatic nonobstructing renal calculi demonstrated that 28% of stones became symptomatic, with 17% requiring surgical intervention and 2% causing asymptomatic hydronephrosis over three years.

Citation: Dropkin BM, Moses RA, Sharma D, Pais VM Jr. The natural history of nonobstructing asymptomatic renal stones managed with active surveillance. J Urol. 2015;193(4):1265-1269.

CPR USE IS HIGH, YET OUTCOMES ARE POOR IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

In a national cohort of hemodialysis patients, receipt of in-hospital CPR was significantly higher (6.3% vs. 0.3%) than the general population, but post-discharge survival was substantially shorter (33 vs. five months).

Citation: Wong SY, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O’Hare AM. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1028-1035. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406.

ULTRASOUND GUIDANCE INCREASES RATE OF SUCCESSFUL FIRST ATTEMPT RADIAL ARTERY CANNULATION

Randomized controlled trial of 749 anesthesia trainees showed that ultrasound guidance increased rate of first attempt radial artery cannulation by 14% when compared to Doppler and palpation (95% CI 5-22%).

Citation: Ueda K, Bayman EO, Johnson C, Odum NJ, Lee JJ. A randomised controlled trial of radial artery cannulation guided by Doppler vs palpation vs ultrasound [published online ahead of print April 8, 2015]. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.13062.

NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EPIDURAL STEROID INJECTIONS AND GABAPENTIN FOR TREATMENT OF LUMBOSACRAL RADICULAR PAIN

Multicenter, randomized study found no difference in lumbosacral radicular pain at one and three months in patients treated with epidural steroid injection versus gabapentin.

Citation: Cohen SP, Hanling S, Bicket MC, et al. Epidural steroid injections compared with gabapentin for lumbosacral radicular pain: multicenter randomized double blind comparative efficacy study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1748 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1748.

References

- Smith K. Effective communication with primary care providers. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):671-679.

- Coghlin DT, Leyenaar JK, Shen M, et al. Pediatric discharge content: a multisite assessment of physician preferences and experiences. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(1):9-15.

- Ruth JL, Geskey JM, Shaffer ML, Bramley HP, Paul IM. Evaluating communication between pediatric primary care physicians and hospitalists. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(10):923-928.

- Leyenaar JK, Bergert L, Mallory LA, et al. Pediatric primary care providers’ perspectives regarding hospital discharge communication: a mixed methods analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):61-68.

- Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386.

Clinical question: Can a standardized discharge communication process, coupled with an electronic health record (EHR) system, improve the proportion of completed verbal handoffs from in-hospital physicians to PCPs within 24 hours of patient discharge?

Background: Discharge from the hospital setting is known to be a transition of care fraught with patient safety risks, with more than half of discharged patients experiencing at least one error.1 Previous studies identified core elements that pediatric hospitalists and PCPs consider essential in discharge communication, which included:

- Pending laboratory or test results;

- Follow-up appointments;

- Discharge medications;

- Admission and discharge diagnoses;

- Dates of admission and discharge; and

- Suggested management plan.2

Rates of transmission and receipt of information have been found to be suboptimal after hospital discharge, and PCPs have been found to be less satisfied than hospitalists with communication.2,3 Additionally, PCPs and hospitalists have been found to have incongruent views on who should be responsible for pending labs, adverse events, or status changes, differences which can have safety implications.3 PCPs who refer to general hospitals have been found to report superior completeness of discharge communication compared to freestanding children’s hospitals, where resident physicians are generally responsible for discharge summary completion.4 Standardizing and promoting a process of verbal handoff after hospital discharge may address some of these safety concerns, although a relationship has not been established between aspects of discharge communication and associated adverse clinical outcomes.5

Study design: Quality improvement study using improvement science methods and run charts.

Setting: An urban, 598-bed, freestanding children’s hospital.

Synopsis: A 24/7 telephone operator service had been established at the investigators’ institution that was designed to facilitate communication between providers inside and outside the institution. At baseline, only 52% of hospital medicine (HM) provider discharges had a record of a discharge day call initiated to the PCP. A project team consisting of hospitalists, a chief resident, operator service administrators, and IT analysts identified system issues that led to unsuccessful communication, which facilitated identification of key drivers of improving communication and associated interventions (see Table 1).

Discharging physicians, who were usually residents, were instructed to call the operator at the time of discharge. Operators would page the PCP, and PCPs were expected to return the page within 20 minutes. Discharging physicians were expected to return the call to the operator within two to four minutes. The EHR generated a message to the operator whenever a discharge order was placed for an HM patient, leading the operator to page the discharging physician to initiate the call.

Adaptations after project initiation included:

- Reassigning primary responsibility for discharge phone calls to the daily on-call resident, if the discharging physician was not available.

- Establishing a non-changing pager number on the automated discharge notification that would always reach the appropriate team member.

- Batching discharge phone calls at times of increased resident availability to minimize hold times for PCPs and work interruptions for discharging physicians.

Weekly failure data was generated and reviewed by the improvement team, and a call record was linked to the patient’s medical record. Team-specific and overall results for HM teams were posted weekly on a run-chart. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of completed calls between PCP and HM physician within 24 hours of discharge.

Over the approximately 32-month study period, the percentage of calls initiated improved from 50% to 97% after four interventions. After one year, data was collected to assess percentage of calls completed, a number that rose from 80% in the first eight weeks to a median of 93%, which was sustained for 18 months.

Bottom line: Utilizing improvement methods and reliability science, a process of improving verbal handoffs between hospital-based physicians and PCPs within 24 hours after discharge led to a sustained improvement, to above 90%, in successful verbal handoffs.

Citation: Mussman GM, Vossmeyer MT, Brady PW, Warrick DM, Simmons JM, White CM. Improving the reliability of verbal communication between primary care physicians and pediatric hospitalists at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print May 29, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2392.

Clinical Shorts

MAJORITY OF NONOBSTRUCTING ASYMPTOMATIC RENAL STONES REMAIN ASYMPTOMATIC OVER TIME

Retrospective trial of active surveillance of asymptomatic nonobstructing renal calculi demonstrated that 28% of stones became symptomatic, with 17% requiring surgical intervention and 2% causing asymptomatic hydronephrosis over three years.

Citation: Dropkin BM, Moses RA, Sharma D, Pais VM Jr. The natural history of nonobstructing asymptomatic renal stones managed with active surveillance. J Urol. 2015;193(4):1265-1269.

CPR USE IS HIGH, YET OUTCOMES ARE POOR IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

In a national cohort of hemodialysis patients, receipt of in-hospital CPR was significantly higher (6.3% vs. 0.3%) than the general population, but post-discharge survival was substantially shorter (33 vs. five months).

Citation: Wong SY, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O’Hare AM. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1028-1035. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406.

ULTRASOUND GUIDANCE INCREASES RATE OF SUCCESSFUL FIRST ATTEMPT RADIAL ARTERY CANNULATION

Randomized controlled trial of 749 anesthesia trainees showed that ultrasound guidance increased rate of first attempt radial artery cannulation by 14% when compared to Doppler and palpation (95% CI 5-22%).

Citation: Ueda K, Bayman EO, Johnson C, Odum NJ, Lee JJ. A randomised controlled trial of radial artery cannulation guided by Doppler vs palpation vs ultrasound [published online ahead of print April 8, 2015]. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.13062.

NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EPIDURAL STEROID INJECTIONS AND GABAPENTIN FOR TREATMENT OF LUMBOSACRAL RADICULAR PAIN

Multicenter, randomized study found no difference in lumbosacral radicular pain at one and three months in patients treated with epidural steroid injection versus gabapentin.

Citation: Cohen SP, Hanling S, Bicket MC, et al. Epidural steroid injections compared with gabapentin for lumbosacral radicular pain: multicenter randomized double blind comparative efficacy study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1748 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1748.

References

- Smith K. Effective communication with primary care providers. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):671-679.

- Coghlin DT, Leyenaar JK, Shen M, et al. Pediatric discharge content: a multisite assessment of physician preferences and experiences. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(1):9-15.

- Ruth JL, Geskey JM, Shaffer ML, Bramley HP, Paul IM. Evaluating communication between pediatric primary care physicians and hospitalists. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(10):923-928.

- Leyenaar JK, Bergert L, Mallory LA, et al. Pediatric primary care providers’ perspectives regarding hospital discharge communication: a mixed methods analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):61-68.

- Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386.

Clinical question: Can a standardized discharge communication process, coupled with an electronic health record (EHR) system, improve the proportion of completed verbal handoffs from in-hospital physicians to PCPs within 24 hours of patient discharge?

Background: Discharge from the hospital setting is known to be a transition of care fraught with patient safety risks, with more than half of discharged patients experiencing at least one error.1 Previous studies identified core elements that pediatric hospitalists and PCPs consider essential in discharge communication, which included:

- Pending laboratory or test results;

- Follow-up appointments;

- Discharge medications;

- Admission and discharge diagnoses;

- Dates of admission and discharge; and

- Suggested management plan.2

Rates of transmission and receipt of information have been found to be suboptimal after hospital discharge, and PCPs have been found to be less satisfied than hospitalists with communication.2,3 Additionally, PCPs and hospitalists have been found to have incongruent views on who should be responsible for pending labs, adverse events, or status changes, differences which can have safety implications.3 PCPs who refer to general hospitals have been found to report superior completeness of discharge communication compared to freestanding children’s hospitals, where resident physicians are generally responsible for discharge summary completion.4 Standardizing and promoting a process of verbal handoff after hospital discharge may address some of these safety concerns, although a relationship has not been established between aspects of discharge communication and associated adverse clinical outcomes.5

Study design: Quality improvement study using improvement science methods and run charts.

Setting: An urban, 598-bed, freestanding children’s hospital.