User login

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: Pearls from clinical experience

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

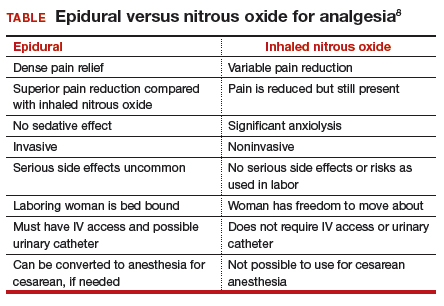

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.

Some coordination with the nurse is essential for optimal timing of administration. Onset of a therapeutic level of pain relief is generally 30 to 60 seconds after inhalation has begun, with rapid resolution after cessation of the inhalation. The patient should thus initiate the inspiration of the gas at the earliest signs of onset of a contraction, so as to achieve maximal analgesia at the peak of the contraction. Waiting until the peak of the contraction to initiate inhalation of the nitrous oxide will not provide effective analgesia, yet will result in sedation after the contraction has ended.

Read about patient satisfaction with inhaled nitrous oxide.

No oversight by an anesthesiologist is required

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produced a clarification statement for definitions of “anesthesia services” (42 CFR 482.52)9 that may be offered by a hospital, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) definitions. CMS, consistent with ASA guidelines, does not define moderate or conscious sedation as “anesthesia,” thus direct oversight by an anesthesiologist is not required. Furthermore, the definition of “minimal sedation,” which is where 50% concentration delivery of inhaled nitrous oxide would be categorized, also does not meet this requirement by CMS.

Women who use inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain typically are satisfied with its use

The use of analog pain scale measurements may not be appropriate in a setting where dissociation from pain might be the primary beneficial effect. Measurements of maternal satisfaction with their analgesic experience support this. The experiences at Vanderbilt University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital show that, while pain relief is limited, like reported in systematic reviews, maternal satisfaction scores for labor analgesia are not different among women who receive inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia, neuraxial analgesia, and those who transition from nitrous to neuraxial analgesia. In fact, published evidence supports extraordinarily high satisfaction in women who plan to use inhaled nitrous oxide, and actually successfully do so, despite only limited degrees of pain relief.10,11 Work to identify the characteristics of women who report success with inhaled nitrous oxide use needs to be performed so that patients can be better selected and informed when making analgesic choices.

Animal research on inhaled nitrous oxide may not translate well to human neonates

A very recent task force convened by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) addressed some of the potential concerns about inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia.12 Per their report:

“the potential teratogenic effect of N2O observed in experimental models cannot be extrapolated to humans. There is a lack of evidence for an association between N2O and reproductive toxicity. The incidence of health hazards and abortion was not shown to be higher in women exposed to, or spouses of men exposed to N2O than those who were not so exposed. Moreover, the incidence of congenital malformations was not higher among women who received N2O for anaesthesia during the first trimester of pregnancy nor during anaesthesia management for cervical cerclage, nor for surgery in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.”

There is a theoretical concern of an increase in neuronal apoptosis in neonates, demonstrated in laboratory animals in anesthetic concentrations, but the human relevance of this is not clear, since the data on animal developmental neurotoxicity is generally combined with data wherein potent inhalational anesthetic agents were also used, not nitrous oxide alone.13 The analgesic doses and time of exposure of inhaled nitrous oxide administered for labor analgesia are well below those required for these changes, as subanesthetic doses are associated with minimal changes, if any, in laboratory animals.

No labor analgesic is without the potential for fetal effects, and alternative labor analgesics such as systemic opioids in higher doses also may have potential adverse effects on the fetus, such as fetal heart rate effects or early tone, alertness, and breastfeeding difficulties. The low solubility and short half-life of inhaled nitrous oxide contribute to low absorption by tissues, thus contributing to the safety of this agent. Nitrous oxide via inhalation for sedation during elective cesarean has been reported to show no adverse effects on neonatal Apgar scores.14

Modern equipment keeps occupational exposure to nitrous oxide safe

One retrospective review of women exposed to high concentrations of inhaled nitrous oxide reported reduced fertility.15 However, the only effects on fertility were seen when nitrous was used without scavenging equipment, and in high concentrations. Moreover, that study examined dental offices, where nitrous was free flowing during procedures—quite a different setting than the intermittent inhalation, demand-valve modality as is used during labor—and when using appropriate modern, FDA-approved equipment, and scavenging devices. Per the recent ESA task force12:

“Members of the task force agreed that, despite theoretical concerns and laboratory data, there is no evidence indicating that the use of N2O in a clinically relevant setting would increase health risk in patients or providers exposed to this drug. With the ubiquitous availability of scavenging systems in the modern operating room, the health concern for medical staff has decreased dramatically. Properly operating scavenging systems reduce N2O concentrations by more than 70%, thereby efficiently keeping ambient N2O levels well below official limits.”

The ESA task force concludes: “An extensive amount of clinical evidence indicates that N2O can be used safely for procedural pain management, for labour pain, and for anxiolysis and sedation in dentistry.”12

Two important reminders

Inhaled nitrous oxide has been a central component of the labor pain relief menu in most of the rest of the world for decades, and the safety record is impeccable. This agent has now had extensive and growing experience in American maternity units. Remember 2 critical points: 1) patient selection is key, 2) analgesia is not like that provided by regional anesthetic techniques such as an epidural.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153-167.

- Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl nature):S110-S126.

- Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):468-478.

- Migliaccio L, Lawton R, Leeman L, Holbrook A. Initiating intrapartum nitrous oxide in an academic hospital: considerations and challenges. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):358-362.

- Markley JC, Rollins MD. Non-neuraxial labor analgesia: options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(2);350-364.

- Bobb LE, Farber MK, McGovern C, Camann W. Does nitrous oxide labor analgesia influence the pattern of neuraxial analgesia usage? An impact study at an academic medical center. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:54-57.

- Sutton CD, Butwick AJ, Riley ET, Carvalho B. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: utilization and predictors of conversion to neuraxial analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:40-45.

- Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(3-4):e126-e131.

- 42 CFR 482.52 - Condition of participation: Anesthesia services. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec482-52. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Richardson MG, Lopez BM, Baysinger CL, Shotwell MS, Chestnut DH. Nitrous oxide during labor: maternal satisfaction does not depend exclusively on analgesic effectiveness. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):548-553.

- Camann W. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction, and excellence in obstetric anesthesia: a surprisingly complex relationship. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):383-385.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology Task Force on Use of Nitrous Oxide in Clinical Anaesthetic Practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: an expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(8):517-520.

- Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1387-1390.

- Vallejo MC, Phelps AL, Shepherd CJ, Kaul B, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S. Nitrous oxide anxiolysis for elective cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(7):543-548.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, et al. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):993-997.

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.

Some coordination with the nurse is essential for optimal timing of administration. Onset of a therapeutic level of pain relief is generally 30 to 60 seconds after inhalation has begun, with rapid resolution after cessation of the inhalation. The patient should thus initiate the inspiration of the gas at the earliest signs of onset of a contraction, so as to achieve maximal analgesia at the peak of the contraction. Waiting until the peak of the contraction to initiate inhalation of the nitrous oxide will not provide effective analgesia, yet will result in sedation after the contraction has ended.

Read about patient satisfaction with inhaled nitrous oxide.

No oversight by an anesthesiologist is required

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produced a clarification statement for definitions of “anesthesia services” (42 CFR 482.52)9 that may be offered by a hospital, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) definitions. CMS, consistent with ASA guidelines, does not define moderate or conscious sedation as “anesthesia,” thus direct oversight by an anesthesiologist is not required. Furthermore, the definition of “minimal sedation,” which is where 50% concentration delivery of inhaled nitrous oxide would be categorized, also does not meet this requirement by CMS.

Women who use inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain typically are satisfied with its use

The use of analog pain scale measurements may not be appropriate in a setting where dissociation from pain might be the primary beneficial effect. Measurements of maternal satisfaction with their analgesic experience support this. The experiences at Vanderbilt University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital show that, while pain relief is limited, like reported in systematic reviews, maternal satisfaction scores for labor analgesia are not different among women who receive inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia, neuraxial analgesia, and those who transition from nitrous to neuraxial analgesia. In fact, published evidence supports extraordinarily high satisfaction in women who plan to use inhaled nitrous oxide, and actually successfully do so, despite only limited degrees of pain relief.10,11 Work to identify the characteristics of women who report success with inhaled nitrous oxide use needs to be performed so that patients can be better selected and informed when making analgesic choices.

Animal research on inhaled nitrous oxide may not translate well to human neonates

A very recent task force convened by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) addressed some of the potential concerns about inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia.12 Per their report:

“the potential teratogenic effect of N2O observed in experimental models cannot be extrapolated to humans. There is a lack of evidence for an association between N2O and reproductive toxicity. The incidence of health hazards and abortion was not shown to be higher in women exposed to, or spouses of men exposed to N2O than those who were not so exposed. Moreover, the incidence of congenital malformations was not higher among women who received N2O for anaesthesia during the first trimester of pregnancy nor during anaesthesia management for cervical cerclage, nor for surgery in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.”

There is a theoretical concern of an increase in neuronal apoptosis in neonates, demonstrated in laboratory animals in anesthetic concentrations, but the human relevance of this is not clear, since the data on animal developmental neurotoxicity is generally combined with data wherein potent inhalational anesthetic agents were also used, not nitrous oxide alone.13 The analgesic doses and time of exposure of inhaled nitrous oxide administered for labor analgesia are well below those required for these changes, as subanesthetic doses are associated with minimal changes, if any, in laboratory animals.

No labor analgesic is without the potential for fetal effects, and alternative labor analgesics such as systemic opioids in higher doses also may have potential adverse effects on the fetus, such as fetal heart rate effects or early tone, alertness, and breastfeeding difficulties. The low solubility and short half-life of inhaled nitrous oxide contribute to low absorption by tissues, thus contributing to the safety of this agent. Nitrous oxide via inhalation for sedation during elective cesarean has been reported to show no adverse effects on neonatal Apgar scores.14

Modern equipment keeps occupational exposure to nitrous oxide safe

One retrospective review of women exposed to high concentrations of inhaled nitrous oxide reported reduced fertility.15 However, the only effects on fertility were seen when nitrous was used without scavenging equipment, and in high concentrations. Moreover, that study examined dental offices, where nitrous was free flowing during procedures—quite a different setting than the intermittent inhalation, demand-valve modality as is used during labor—and when using appropriate modern, FDA-approved equipment, and scavenging devices. Per the recent ESA task force12:

“Members of the task force agreed that, despite theoretical concerns and laboratory data, there is no evidence indicating that the use of N2O in a clinically relevant setting would increase health risk in patients or providers exposed to this drug. With the ubiquitous availability of scavenging systems in the modern operating room, the health concern for medical staff has decreased dramatically. Properly operating scavenging systems reduce N2O concentrations by more than 70%, thereby efficiently keeping ambient N2O levels well below official limits.”

The ESA task force concludes: “An extensive amount of clinical evidence indicates that N2O can be used safely for procedural pain management, for labour pain, and for anxiolysis and sedation in dentistry.”12

Two important reminders

Inhaled nitrous oxide has been a central component of the labor pain relief menu in most of the rest of the world for decades, and the safety record is impeccable. This agent has now had extensive and growing experience in American maternity units. Remember 2 critical points: 1) patient selection is key, 2) analgesia is not like that provided by regional anesthetic techniques such as an epidural.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.

Some coordination with the nurse is essential for optimal timing of administration. Onset of a therapeutic level of pain relief is generally 30 to 60 seconds after inhalation has begun, with rapid resolution after cessation of the inhalation. The patient should thus initiate the inspiration of the gas at the earliest signs of onset of a contraction, so as to achieve maximal analgesia at the peak of the contraction. Waiting until the peak of the contraction to initiate inhalation of the nitrous oxide will not provide effective analgesia, yet will result in sedation after the contraction has ended.

Read about patient satisfaction with inhaled nitrous oxide.

No oversight by an anesthesiologist is required

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produced a clarification statement for definitions of “anesthesia services” (42 CFR 482.52)9 that may be offered by a hospital, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) definitions. CMS, consistent with ASA guidelines, does not define moderate or conscious sedation as “anesthesia,” thus direct oversight by an anesthesiologist is not required. Furthermore, the definition of “minimal sedation,” which is where 50% concentration delivery of inhaled nitrous oxide would be categorized, also does not meet this requirement by CMS.

Women who use inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain typically are satisfied with its use

The use of analog pain scale measurements may not be appropriate in a setting where dissociation from pain might be the primary beneficial effect. Measurements of maternal satisfaction with their analgesic experience support this. The experiences at Vanderbilt University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital show that, while pain relief is limited, like reported in systematic reviews, maternal satisfaction scores for labor analgesia are not different among women who receive inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia, neuraxial analgesia, and those who transition from nitrous to neuraxial analgesia. In fact, published evidence supports extraordinarily high satisfaction in women who plan to use inhaled nitrous oxide, and actually successfully do so, despite only limited degrees of pain relief.10,11 Work to identify the characteristics of women who report success with inhaled nitrous oxide use needs to be performed so that patients can be better selected and informed when making analgesic choices.

Animal research on inhaled nitrous oxide may not translate well to human neonates

A very recent task force convened by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) addressed some of the potential concerns about inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia.12 Per their report:

“the potential teratogenic effect of N2O observed in experimental models cannot be extrapolated to humans. There is a lack of evidence for an association between N2O and reproductive toxicity. The incidence of health hazards and abortion was not shown to be higher in women exposed to, or spouses of men exposed to N2O than those who were not so exposed. Moreover, the incidence of congenital malformations was not higher among women who received N2O for anaesthesia during the first trimester of pregnancy nor during anaesthesia management for cervical cerclage, nor for surgery in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.”

There is a theoretical concern of an increase in neuronal apoptosis in neonates, demonstrated in laboratory animals in anesthetic concentrations, but the human relevance of this is not clear, since the data on animal developmental neurotoxicity is generally combined with data wherein potent inhalational anesthetic agents were also used, not nitrous oxide alone.13 The analgesic doses and time of exposure of inhaled nitrous oxide administered for labor analgesia are well below those required for these changes, as subanesthetic doses are associated with minimal changes, if any, in laboratory animals.

No labor analgesic is without the potential for fetal effects, and alternative labor analgesics such as systemic opioids in higher doses also may have potential adverse effects on the fetus, such as fetal heart rate effects or early tone, alertness, and breastfeeding difficulties. The low solubility and short half-life of inhaled nitrous oxide contribute to low absorption by tissues, thus contributing to the safety of this agent. Nitrous oxide via inhalation for sedation during elective cesarean has been reported to show no adverse effects on neonatal Apgar scores.14

Modern equipment keeps occupational exposure to nitrous oxide safe

One retrospective review of women exposed to high concentrations of inhaled nitrous oxide reported reduced fertility.15 However, the only effects on fertility were seen when nitrous was used without scavenging equipment, and in high concentrations. Moreover, that study examined dental offices, where nitrous was free flowing during procedures—quite a different setting than the intermittent inhalation, demand-valve modality as is used during labor—and when using appropriate modern, FDA-approved equipment, and scavenging devices. Per the recent ESA task force12:

“Members of the task force agreed that, despite theoretical concerns and laboratory data, there is no evidence indicating that the use of N2O in a clinically relevant setting would increase health risk in patients or providers exposed to this drug. With the ubiquitous availability of scavenging systems in the modern operating room, the health concern for medical staff has decreased dramatically. Properly operating scavenging systems reduce N2O concentrations by more than 70%, thereby efficiently keeping ambient N2O levels well below official limits.”

The ESA task force concludes: “An extensive amount of clinical evidence indicates that N2O can be used safely for procedural pain management, for labour pain, and for anxiolysis and sedation in dentistry.”12

Two important reminders

Inhaled nitrous oxide has been a central component of the labor pain relief menu in most of the rest of the world for decades, and the safety record is impeccable. This agent has now had extensive and growing experience in American maternity units. Remember 2 critical points: 1) patient selection is key, 2) analgesia is not like that provided by regional anesthetic techniques such as an epidural.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153-167.

- Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl nature):S110-S126.

- Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):468-478.

- Migliaccio L, Lawton R, Leeman L, Holbrook A. Initiating intrapartum nitrous oxide in an academic hospital: considerations and challenges. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):358-362.

- Markley JC, Rollins MD. Non-neuraxial labor analgesia: options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(2);350-364.

- Bobb LE, Farber MK, McGovern C, Camann W. Does nitrous oxide labor analgesia influence the pattern of neuraxial analgesia usage? An impact study at an academic medical center. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:54-57.

- Sutton CD, Butwick AJ, Riley ET, Carvalho B. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: utilization and predictors of conversion to neuraxial analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:40-45.

- Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(3-4):e126-e131.

- 42 CFR 482.52 - Condition of participation: Anesthesia services. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec482-52. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Richardson MG, Lopez BM, Baysinger CL, Shotwell MS, Chestnut DH. Nitrous oxide during labor: maternal satisfaction does not depend exclusively on analgesic effectiveness. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):548-553.

- Camann W. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction, and excellence in obstetric anesthesia: a surprisingly complex relationship. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):383-385.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology Task Force on Use of Nitrous Oxide in Clinical Anaesthetic Practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: an expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(8):517-520.

- Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1387-1390.

- Vallejo MC, Phelps AL, Shepherd CJ, Kaul B, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S. Nitrous oxide anxiolysis for elective cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(7):543-548.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, et al. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):993-997.

- Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153-167.

- Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl nature):S110-S126.

- Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):468-478.

- Migliaccio L, Lawton R, Leeman L, Holbrook A. Initiating intrapartum nitrous oxide in an academic hospital: considerations and challenges. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):358-362.

- Markley JC, Rollins MD. Non-neuraxial labor analgesia: options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(2);350-364.

- Bobb LE, Farber MK, McGovern C, Camann W. Does nitrous oxide labor analgesia influence the pattern of neuraxial analgesia usage? An impact study at an academic medical center. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:54-57.

- Sutton CD, Butwick AJ, Riley ET, Carvalho B. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: utilization and predictors of conversion to neuraxial analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:40-45.

- Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(3-4):e126-e131.

- 42 CFR 482.52 - Condition of participation: Anesthesia services. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec482-52. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Richardson MG, Lopez BM, Baysinger CL, Shotwell MS, Chestnut DH. Nitrous oxide during labor: maternal satisfaction does not depend exclusively on analgesic effectiveness. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):548-553.

- Camann W. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction, and excellence in obstetric anesthesia: a surprisingly complex relationship. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):383-385.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology Task Force on Use of Nitrous Oxide in Clinical Anaesthetic Practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: an expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(8):517-520.

- Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1387-1390.

- Vallejo MC, Phelps AL, Shepherd CJ, Kaul B, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S. Nitrous oxide anxiolysis for elective cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(7):543-548.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, et al. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):993-997.

Nitrous oxide for labor pain

Neuraxial anesthesia, including epidural and combined spinal-epidural anesthetics, are the “gold standard” interventions for pain relief during labor because they provide a superb combination of reliable pain relief and safety for the mother and child.1 Many US birthing centers also offer additional options for managing labor pain, including continuous labor support,2 hydrotherapy,3 and parenteral opioids.4 In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved equipment to deliver a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, which has offered a new option for laboring mothers.

Nitrous oxide is widely used for labor pain in the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.5 In the United States, nitrous oxide has been a long-standing and common adjunct to general anesthetics, although it recently has fallen out of favor in place of better, more rapidly acting inhalation and intravenous general anesthetics. With these agents not suitable for labor analgesic use, however, nitrous oxide is undergoing a resurgence in popularity for obstetric analgesia in the United States, and we believe that it will evolve to have a prominent place among our interventions for labor pain.6 In this editorial, we detail the mechanism of action and the equipment’s use, as well as benefits for patients and cautions for clinicians.

How does nitrous oxide work?

Pharmacology. Nitrous oxide (N2O) was first synthesized by Joseph Priestley in 1772 and was used as an anesthetic for dental surgery in the mid-1800s. In the late 19th Century, nitrous oxide was tested as an agent for labor analgesia.7 It was introduced into clinical practice in the United Kingdom in the 1930s.8

The mechanism of action of nitrous oxide is not fully characterized. It is thought that the gas may produce analgesia by activating the endogenous opioid and noradrenergic systems, which in turn, modulate spinal cord transmission of pain signals.5

Administration to the laboring mother. For labor analgesia, nitrous oxide is typically administered as a mix of 50% N2O and 50% O2 using a portable unit with a gas mixer that is fed by small tanks of N2O and O2 or with a valve fed by a single tank containing a mixture of both N2O and O2. The portable units approved by the FDA contain an oxygen fail-safe system that ensures delivery of an appropriate oxygen concentration. The portable unit also contains a gas scavenging system that is attached to wall suction. The breathing circuit has a mask or a mouthpiece (according to patient preference) and demand valve. The patient places the mask over her nose and mouth, or uses just her mouth for the mouthpiece. With inhalation, the demand valve opens, releasing the gas mixture. On exhalation, the valve shunts the exhaled gases to the scavenging system.

Proper and safe use requires adherence to the principles of a true “patient-controlled” protocol. Only the patient is permitted to place the mask or mouthpiece over her nose and/or mouth. If the patient becomes drowsy, such that she cannot hold the mask to her face, then the internal demand valve will not deliver nitrous oxide and she will return to breathing room air. No one should hold the mask over the patient’s nose or mouth, and the mask should not be fixed in place with elastic bands because these actions may result in the inhalation of too much nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide has a rapid onset of action after inhalation and its action quickly dissipates after discontinuing inhalation. There is likely a dose-response relationship, with greater use of the nitrous oxide producing more drowsiness. With the intermittent inhalation method, the laboring patient using nitrous oxide is advised to initiate inhalation of nitrous oxide about 30 seconds before the onset of a contraction and discontinue inhalation at the peak of the contraction.

There is no time limit to the use of nitrous oxide. It can be used for hours during labor or only briefly for a particularly painful part of labor, such as during rapid cervical dilation or during the later portions of the second stage.

Patients report that nitrous oxide does not completely relieve pain but creates a diminished perception of the pain.9 As many as one-third of women are nonresponders and report no significant pain improvement with nitrous oxide use.10

The main side effects of inhalation of the gas are nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and drowsiness. Nausea has been reported in 5% to 40% of women, and vomiting has been reported in up to 15% of women using nitrous oxide.11

Cautions

Contraindications to nitrous oxide include a baseline arterial oxygenation saturation less than 95% on room air, acute asthma, emphysema, or pneumothorax, or any other air-filled compartment within the body, such as bowel obstruction or pneumocephalus. (Nitrous oxide can displace nitrogen from closed body spaces, which may lead to an increase in the volume of the closed space.12)

Nitrous oxide inactivates vitamin B12 by oxidation; therefore, vitamin B12 deficiency or related disorders may be considered a relative contraindication. However, compared with more extensive continuous use, such as during prolonged general anesthesia, intermittent use for a limited time during labor is associated with minimal to no hematologic effects.

If a laboring woman is using N2O, parenteral opioids should be administered only with great caution by an experienced clinician.

What do the data indicate?

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recently invited the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center to review the world literature on nitrous oxide for labor pain and to provide a summary of the research. Fifty-eight publications were identified, with 46 rated as poor quality.11,13 Given this overall poor quality of available research, many of the recommendations concerning the use of nitrous oxide for labor pain are based on clinical experience and expert opinion.

The experts concluded that, for the relief of labor pain, neuraxial anesthesia was more effective than nitrous oxide inhalation. In one randomized trial included in their systematic review, nulliparous laboring women were randomly assigned to neuraxial anesthesia or nitrous oxide plus meperidine.14 About 94% of nulliparous laboring women reported satisfaction with neuraxial anesthesia, compared with 54% treated with nitrous oxide and meperidine.14

Nitrous oxide is believed to be generally safe for mother and fetus. Its use does not impact the newborn Apgar score15 or alter uterine

contractility.16

Considering a nitrous oxide program for your birthing unit? Helpful hints to get started.

Catherine McGovern, RN, MSN, CNM

- Do your research to determine which type of equipment is right for the size and volume of your organization.

You need to consider ease of access and use for staff to bring this option to the bedside in a prompt and safe manner. Initial research includes visiting or speaking with practitioners on units currently using nitrous oxide. Use of nitrous oxide is growing, and networking is helpful in terms of planning your program. Making sure you have the correct gas line connectors for oxygen as well as for suction when using a scavenger system is a preliminary necessity. - Determine storage ability.

Your environmental safety officer is a good resource to determine location and regulations regarding safe storage as well as tank capacity. He or she also can help you determine where else in your organization nitrous oxide is used so you may be able to develop your unit-specific protocol from hospital-wide policy that is already in place. - Collaborate on a protocol.

After determining which type of equipment is best for you, propose the idea to committees that can contribute to the development of pain and sedation management protocols. The anesthesia department, pain committee, and postoperative pain management teams are knowledgeable resources and can help you write a safe protocol. Keep as the main focus the safe application and use of nitrous oxide for various patient populations. Potential medication interactions and contraindications for use should be discussed and included in a protocol.

One more department you want to include in your planning is infection control. For our unit, reviewing various types of equipment to determine the best infection control revealed some interesting design benefits to reduce infection risk. Because the nitrous oxide equipment would be mobile, the types of filter options, disposal options, and cleaning ability are important components for final equipment choice. - Include all parties in training and final roll out.

Once you develop your policy with input from all stakeholders, make sure you share it early and often before you go live. Include midwives, physicians, nurses, technicians, and administrative staff in training, which will help to dispel myths and increase awareness of availability within your unit. Provide background information to all trainees to ensure safe use and appropriate patient selection.

The most important determinant of success is the formation of an interprofessional team that works well together to develop a safe clinician- and patient-friendly program for the use of nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide, a bridge to an epidural or a natural childbirth

Many women start labor unsure about whether they want to use an epidural. For these women, nitrous oxide may be an option for reducing labor pain, thereby giving the woman more time to make a decision about whether to have an epidural anesthetic. In our practice, a significant percentage of women who use nitrous oxide early in labor subsequently request a neuraxial anesthetic. However, many women planning natural childbirth use nitrous oxide to reduce labor pain and successfully achieve their goal.

Postpartum pain reliever

Some women deliver without the use of any pain medicine. Sometimes birth is complicated by perineal lacerations requiring significant surgical repair. If a woman does not have adequate analgesia after injection of a local anesthetic, nitrous oxide may help reduce her pain during the perineal repair and facilitate quick completion of the procedure by allowing her to remain still. N2O also has been used to facilitate analgesia during manual removal of the placenta.

We predict an expanding role

There are many pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for managing labor pain, including a supportive birth environment, touch and massage, maternal positioning, relaxation and breathing techniques, continuous labor support, hydrotherapy, opioids, and neuraxial anesthesia. Midwives, labor nurses, and physicians have championed increasing the availability of nitrous oxide to laboring women in US birthing centers.17–20 With the FDA approval of inexpensive portable nitrous oxide units, it is likely that we will witness a resurgence of its use and gain important clinical experience in the role of nitrous oxide for managing labor pain.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Amin-Somuah M, Smyth R, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD000331.

2. Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr JG, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD003766.

3. Cluett ER, Burns E. Immersion in water in labour and birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD000111.

4. Ullman R, Smith LA, Burns E, Mori R, Dowswell T. Parenteral opioids for maternal pain management in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(9):CD007396.

5. Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl Nature):S110–S126.

6. Klomp T, van Poppel M, Jones L, Lazet J, Di Nisio M, Lagro-Janssen A. Inhaled analgesia for pain management in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD009351.

7. Richards W, Parbrook G, Wilson J. Stanislav Klikovitch (1853-1910). Pioneer of nitrous oxide and oxygen analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1976;31(7):933–940.

8. Minnitt R. Self-administered anesthesia in childbirth. Br Med J. 1934;1:501–503.

9. Camann W, Alexander K. Easy labor: Every Woman’s Guide to Choosing Less Pain and More Joy during Childbirth. New York: Ballantine Books; 2007.

10. Rosen M, Mushin WW, Jones PL, Jones EV. Field trial of methoxyflurane, nitrous oxide, and trichloroethylene as obstetric analgesics. Br Med J. 1969;3(5665):263–267.

11. Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153–167.

12. Eger EI 2nd, Saidman LJ. Hazards of nitrous oxide anesthesia in bowel obstruction and pneumothorax. Anesthesiology. 1965;26:61–66.

13. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 67. August 2012. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/260/1175/CER67_NitrousOxideLaborPain_FinalReport_20120817.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2014.

14. Leong EW, Sivanesaratnam V, Oh LL, Chan YK. Epidural analgesia in primigravidae in spontaneous labor at term: a prospective study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2000;26(4):271–275.

15. Clinical trials of different concentrations of oxygen and nitrous oxide for obstetric analgesia. Report to the Medical Research Council of the Committee on Nitrous Oxide and Oxygen Analgesia in Midwifery. Br Med J. 1970;1(5698):709–713.

16. Vasicka A, Kretchmer H. Effect of conduction and inhalation anesthesia on uterine contractions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;82:600–611.

17. Rooks JP. Labor pain management other than neuraxial: what do we know and where do we go next? Birth. 2012;39(4):318–322.

18. American College of Nurse-Midwives. From the American College of Nurse-Midwives. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(3):292–296.

19. Bishop JT. Administration of nitrous oxide in labor: expanding the options for women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52(3):308–309.

20. Rooks JP. Nitrous oxide for pain in labor—why not in the United States? Birth. 2007;34(1):3–5.

Neuraxial anesthesia, including epidural and combined spinal-epidural anesthetics, are the “gold standard” interventions for pain relief during labor because they provide a superb combination of reliable pain relief and safety for the mother and child.1 Many US birthing centers also offer additional options for managing labor pain, including continuous labor support,2 hydrotherapy,3 and parenteral opioids.4 In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved equipment to deliver a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, which has offered a new option for laboring mothers.

Nitrous oxide is widely used for labor pain in the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.5 In the United States, nitrous oxide has been a long-standing and common adjunct to general anesthetics, although it recently has fallen out of favor in place of better, more rapidly acting inhalation and intravenous general anesthetics. With these agents not suitable for labor analgesic use, however, nitrous oxide is undergoing a resurgence in popularity for obstetric analgesia in the United States, and we believe that it will evolve to have a prominent place among our interventions for labor pain.6 In this editorial, we detail the mechanism of action and the equipment’s use, as well as benefits for patients and cautions for clinicians.

How does nitrous oxide work?

Pharmacology. Nitrous oxide (N2O) was first synthesized by Joseph Priestley in 1772 and was used as an anesthetic for dental surgery in the mid-1800s. In the late 19th Century, nitrous oxide was tested as an agent for labor analgesia.7 It was introduced into clinical practice in the United Kingdom in the 1930s.8

The mechanism of action of nitrous oxide is not fully characterized. It is thought that the gas may produce analgesia by activating the endogenous opioid and noradrenergic systems, which in turn, modulate spinal cord transmission of pain signals.5

Administration to the laboring mother. For labor analgesia, nitrous oxide is typically administered as a mix of 50% N2O and 50% O2 using a portable unit with a gas mixer that is fed by small tanks of N2O and O2 or with a valve fed by a single tank containing a mixture of both N2O and O2. The portable units approved by the FDA contain an oxygen fail-safe system that ensures delivery of an appropriate oxygen concentration. The portable unit also contains a gas scavenging system that is attached to wall suction. The breathing circuit has a mask or a mouthpiece (according to patient preference) and demand valve. The patient places the mask over her nose and mouth, or uses just her mouth for the mouthpiece. With inhalation, the demand valve opens, releasing the gas mixture. On exhalation, the valve shunts the exhaled gases to the scavenging system.

Proper and safe use requires adherence to the principles of a true “patient-controlled” protocol. Only the patient is permitted to place the mask or mouthpiece over her nose and/or mouth. If the patient becomes drowsy, such that she cannot hold the mask to her face, then the internal demand valve will not deliver nitrous oxide and she will return to breathing room air. No one should hold the mask over the patient’s nose or mouth, and the mask should not be fixed in place with elastic bands because these actions may result in the inhalation of too much nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide has a rapid onset of action after inhalation and its action quickly dissipates after discontinuing inhalation. There is likely a dose-response relationship, with greater use of the nitrous oxide producing more drowsiness. With the intermittent inhalation method, the laboring patient using nitrous oxide is advised to initiate inhalation of nitrous oxide about 30 seconds before the onset of a contraction and discontinue inhalation at the peak of the contraction.

There is no time limit to the use of nitrous oxide. It can be used for hours during labor or only briefly for a particularly painful part of labor, such as during rapid cervical dilation or during the later portions of the second stage.

Patients report that nitrous oxide does not completely relieve pain but creates a diminished perception of the pain.9 As many as one-third of women are nonresponders and report no significant pain improvement with nitrous oxide use.10

The main side effects of inhalation of the gas are nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and drowsiness. Nausea has been reported in 5% to 40% of women, and vomiting has been reported in up to 15% of women using nitrous oxide.11

Cautions

Contraindications to nitrous oxide include a baseline arterial oxygenation saturation less than 95% on room air, acute asthma, emphysema, or pneumothorax, or any other air-filled compartment within the body, such as bowel obstruction or pneumocephalus. (Nitrous oxide can displace nitrogen from closed body spaces, which may lead to an increase in the volume of the closed space.12)

Nitrous oxide inactivates vitamin B12 by oxidation; therefore, vitamin B12 deficiency or related disorders may be considered a relative contraindication. However, compared with more extensive continuous use, such as during prolonged general anesthesia, intermittent use for a limited time during labor is associated with minimal to no hematologic effects.

If a laboring woman is using N2O, parenteral opioids should be administered only with great caution by an experienced clinician.

What do the data indicate?

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recently invited the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center to review the world literature on nitrous oxide for labor pain and to provide a summary of the research. Fifty-eight publications were identified, with 46 rated as poor quality.11,13 Given this overall poor quality of available research, many of the recommendations concerning the use of nitrous oxide for labor pain are based on clinical experience and expert opinion.

The experts concluded that, for the relief of labor pain, neuraxial anesthesia was more effective than nitrous oxide inhalation. In one randomized trial included in their systematic review, nulliparous laboring women were randomly assigned to neuraxial anesthesia or nitrous oxide plus meperidine.14 About 94% of nulliparous laboring women reported satisfaction with neuraxial anesthesia, compared with 54% treated with nitrous oxide and meperidine.14

Nitrous oxide is believed to be generally safe for mother and fetus. Its use does not impact the newborn Apgar score15 or alter uterine

contractility.16

Considering a nitrous oxide program for your birthing unit? Helpful hints to get started.

Catherine McGovern, RN, MSN, CNM

- Do your research to determine which type of equipment is right for the size and volume of your organization.

You need to consider ease of access and use for staff to bring this option to the bedside in a prompt and safe manner. Initial research includes visiting or speaking with practitioners on units currently using nitrous oxide. Use of nitrous oxide is growing, and networking is helpful in terms of planning your program. Making sure you have the correct gas line connectors for oxygen as well as for suction when using a scavenger system is a preliminary necessity. - Determine storage ability.

Your environmental safety officer is a good resource to determine location and regulations regarding safe storage as well as tank capacity. He or she also can help you determine where else in your organization nitrous oxide is used so you may be able to develop your unit-specific protocol from hospital-wide policy that is already in place. - Collaborate on a protocol.

After determining which type of equipment is best for you, propose the idea to committees that can contribute to the development of pain and sedation management protocols. The anesthesia department, pain committee, and postoperative pain management teams are knowledgeable resources and can help you write a safe protocol. Keep as the main focus the safe application and use of nitrous oxide for various patient populations. Potential medication interactions and contraindications for use should be discussed and included in a protocol.

One more department you want to include in your planning is infection control. For our unit, reviewing various types of equipment to determine the best infection control revealed some interesting design benefits to reduce infection risk. Because the nitrous oxide equipment would be mobile, the types of filter options, disposal options, and cleaning ability are important components for final equipment choice. - Include all parties in training and final roll out.

Once you develop your policy with input from all stakeholders, make sure you share it early and often before you go live. Include midwives, physicians, nurses, technicians, and administrative staff in training, which will help to dispel myths and increase awareness of availability within your unit. Provide background information to all trainees to ensure safe use and appropriate patient selection.

The most important determinant of success is the formation of an interprofessional team that works well together to develop a safe clinician- and patient-friendly program for the use of nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide, a bridge to an epidural or a natural childbirth

Many women start labor unsure about whether they want to use an epidural. For these women, nitrous oxide may be an option for reducing labor pain, thereby giving the woman more time to make a decision about whether to have an epidural anesthetic. In our practice, a significant percentage of women who use nitrous oxide early in labor subsequently request a neuraxial anesthetic. However, many women planning natural childbirth use nitrous oxide to reduce labor pain and successfully achieve their goal.

Postpartum pain reliever

Some women deliver without the use of any pain medicine. Sometimes birth is complicated by perineal lacerations requiring significant surgical repair. If a woman does not have adequate analgesia after injection of a local anesthetic, nitrous oxide may help reduce her pain during the perineal repair and facilitate quick completion of the procedure by allowing her to remain still. N2O also has been used to facilitate analgesia during manual removal of the placenta.

We predict an expanding role

There are many pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for managing labor pain, including a supportive birth environment, touch and massage, maternal positioning, relaxation and breathing techniques, continuous labor support, hydrotherapy, opioids, and neuraxial anesthesia. Midwives, labor nurses, and physicians have championed increasing the availability of nitrous oxide to laboring women in US birthing centers.17–20 With the FDA approval of inexpensive portable nitrous oxide units, it is likely that we will witness a resurgence of its use and gain important clinical experience in the role of nitrous oxide for managing labor pain.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Neuraxial anesthesia, including epidural and combined spinal-epidural anesthetics, are the “gold standard” interventions for pain relief during labor because they provide a superb combination of reliable pain relief and safety for the mother and child.1 Many US birthing centers also offer additional options for managing labor pain, including continuous labor support,2 hydrotherapy,3 and parenteral opioids.4 In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved equipment to deliver a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, which has offered a new option for laboring mothers.

Nitrous oxide is widely used for labor pain in the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.5 In the United States, nitrous oxide has been a long-standing and common adjunct to general anesthetics, although it recently has fallen out of favor in place of better, more rapidly acting inhalation and intravenous general anesthetics. With these agents not suitable for labor analgesic use, however, nitrous oxide is undergoing a resurgence in popularity for obstetric analgesia in the United States, and we believe that it will evolve to have a prominent place among our interventions for labor pain.6 In this editorial, we detail the mechanism of action and the equipment’s use, as well as benefits for patients and cautions for clinicians.

How does nitrous oxide work?

Pharmacology. Nitrous oxide (N2O) was first synthesized by Joseph Priestley in 1772 and was used as an anesthetic for dental surgery in the mid-1800s. In the late 19th Century, nitrous oxide was tested as an agent for labor analgesia.7 It was introduced into clinical practice in the United Kingdom in the 1930s.8

The mechanism of action of nitrous oxide is not fully characterized. It is thought that the gas may produce analgesia by activating the endogenous opioid and noradrenergic systems, which in turn, modulate spinal cord transmission of pain signals.5

Administration to the laboring mother. For labor analgesia, nitrous oxide is typically administered as a mix of 50% N2O and 50% O2 using a portable unit with a gas mixer that is fed by small tanks of N2O and O2 or with a valve fed by a single tank containing a mixture of both N2O and O2. The portable units approved by the FDA contain an oxygen fail-safe system that ensures delivery of an appropriate oxygen concentration. The portable unit also contains a gas scavenging system that is attached to wall suction. The breathing circuit has a mask or a mouthpiece (according to patient preference) and demand valve. The patient places the mask over her nose and mouth, or uses just her mouth for the mouthpiece. With inhalation, the demand valve opens, releasing the gas mixture. On exhalation, the valve shunts the exhaled gases to the scavenging system.

Proper and safe use requires adherence to the principles of a true “patient-controlled” protocol. Only the patient is permitted to place the mask or mouthpiece over her nose and/or mouth. If the patient becomes drowsy, such that she cannot hold the mask to her face, then the internal demand valve will not deliver nitrous oxide and she will return to breathing room air. No one should hold the mask over the patient’s nose or mouth, and the mask should not be fixed in place with elastic bands because these actions may result in the inhalation of too much nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide has a rapid onset of action after inhalation and its action quickly dissipates after discontinuing inhalation. There is likely a dose-response relationship, with greater use of the nitrous oxide producing more drowsiness. With the intermittent inhalation method, the laboring patient using nitrous oxide is advised to initiate inhalation of nitrous oxide about 30 seconds before the onset of a contraction and discontinue inhalation at the peak of the contraction.

There is no time limit to the use of nitrous oxide. It can be used for hours during labor or only briefly for a particularly painful part of labor, such as during rapid cervical dilation or during the later portions of the second stage.

Patients report that nitrous oxide does not completely relieve pain but creates a diminished perception of the pain.9 As many as one-third of women are nonresponders and report no significant pain improvement with nitrous oxide use.10

The main side effects of inhalation of the gas are nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and drowsiness. Nausea has been reported in 5% to 40% of women, and vomiting has been reported in up to 15% of women using nitrous oxide.11

Cautions

Contraindications to nitrous oxide include a baseline arterial oxygenation saturation less than 95% on room air, acute asthma, emphysema, or pneumothorax, or any other air-filled compartment within the body, such as bowel obstruction or pneumocephalus. (Nitrous oxide can displace nitrogen from closed body spaces, which may lead to an increase in the volume of the closed space.12)

Nitrous oxide inactivates vitamin B12 by oxidation; therefore, vitamin B12 deficiency or related disorders may be considered a relative contraindication. However, compared with more extensive continuous use, such as during prolonged general anesthesia, intermittent use for a limited time during labor is associated with minimal to no hematologic effects.

If a laboring woman is using N2O, parenteral opioids should be administered only with great caution by an experienced clinician.

What do the data indicate?

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recently invited the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center to review the world literature on nitrous oxide for labor pain and to provide a summary of the research. Fifty-eight publications were identified, with 46 rated as poor quality.11,13 Given this overall poor quality of available research, many of the recommendations concerning the use of nitrous oxide for labor pain are based on clinical experience and expert opinion.

The experts concluded that, for the relief of labor pain, neuraxial anesthesia was more effective than nitrous oxide inhalation. In one randomized trial included in their systematic review, nulliparous laboring women were randomly assigned to neuraxial anesthesia or nitrous oxide plus meperidine.14 About 94% of nulliparous laboring women reported satisfaction with neuraxial anesthesia, compared with 54% treated with nitrous oxide and meperidine.14

Nitrous oxide is believed to be generally safe for mother and fetus. Its use does not impact the newborn Apgar score15 or alter uterine

contractility.16

Considering a nitrous oxide program for your birthing unit? Helpful hints to get started.

Catherine McGovern, RN, MSN, CNM

- Do your research to determine which type of equipment is right for the size and volume of your organization.

You need to consider ease of access and use for staff to bring this option to the bedside in a prompt and safe manner. Initial research includes visiting or speaking with practitioners on units currently using nitrous oxide. Use of nitrous oxide is growing, and networking is helpful in terms of planning your program. Making sure you have the correct gas line connectors for oxygen as well as for suction when using a scavenger system is a preliminary necessity. - Determine storage ability.

Your environmental safety officer is a good resource to determine location and regulations regarding safe storage as well as tank capacity. He or she also can help you determine where else in your organization nitrous oxide is used so you may be able to develop your unit-specific protocol from hospital-wide policy that is already in place. - Collaborate on a protocol.

After determining which type of equipment is best for you, propose the idea to committees that can contribute to the development of pain and sedation management protocols. The anesthesia department, pain committee, and postoperative pain management teams are knowledgeable resources and can help you write a safe protocol. Keep as the main focus the safe application and use of nitrous oxide for various patient populations. Potential medication interactions and contraindications for use should be discussed and included in a protocol.

One more department you want to include in your planning is infection control. For our unit, reviewing various types of equipment to determine the best infection control revealed some interesting design benefits to reduce infection risk. Because the nitrous oxide equipment would be mobile, the types of filter options, disposal options, and cleaning ability are important components for final equipment choice. - Include all parties in training and final roll out.

Once you develop your policy with input from all stakeholders, make sure you share it early and often before you go live. Include midwives, physicians, nurses, technicians, and administrative staff in training, which will help to dispel myths and increase awareness of availability within your unit. Provide background information to all trainees to ensure safe use and appropriate patient selection.

The most important determinant of success is the formation of an interprofessional team that works well together to develop a safe clinician- and patient-friendly program for the use of nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide, a bridge to an epidural or a natural childbirth

Many women start labor unsure about whether they want to use an epidural. For these women, nitrous oxide may be an option for reducing labor pain, thereby giving the woman more time to make a decision about whether to have an epidural anesthetic. In our practice, a significant percentage of women who use nitrous oxide early in labor subsequently request a neuraxial anesthetic. However, many women planning natural childbirth use nitrous oxide to reduce labor pain and successfully achieve their goal.

Postpartum pain reliever

Some women deliver without the use of any pain medicine. Sometimes birth is complicated by perineal lacerations requiring significant surgical repair. If a woman does not have adequate analgesia after injection of a local anesthetic, nitrous oxide may help reduce her pain during the perineal repair and facilitate quick completion of the procedure by allowing her to remain still. N2O also has been used to facilitate analgesia during manual removal of the placenta.

We predict an expanding role

There are many pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for managing labor pain, including a supportive birth environment, touch and massage, maternal positioning, relaxation and breathing techniques, continuous labor support, hydrotherapy, opioids, and neuraxial anesthesia. Midwives, labor nurses, and physicians have championed increasing the availability of nitrous oxide to laboring women in US birthing centers.17–20 With the FDA approval of inexpensive portable nitrous oxide units, it is likely that we will witness a resurgence of its use and gain important clinical experience in the role of nitrous oxide for managing labor pain.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Amin-Somuah M, Smyth R, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD000331.

2. Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr JG, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD003766.

3. Cluett ER, Burns E. Immersion in water in labour and birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD000111.

4. Ullman R, Smith LA, Burns E, Mori R, Dowswell T. Parenteral opioids for maternal pain management in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(9):CD007396.

5. Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl Nature):S110–S126.

6. Klomp T, van Poppel M, Jones L, Lazet J, Di Nisio M, Lagro-Janssen A. Inhaled analgesia for pain management in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD009351.

7. Richards W, Parbrook G, Wilson J. Stanislav Klikovitch (1853-1910). Pioneer of nitrous oxide and oxygen analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1976;31(7):933–940.

8. Minnitt R. Self-administered anesthesia in childbirth. Br Med J. 1934;1:501–503.