User login

A Mission for Graduate Medical Education at VA

More than 65% of all physicians who train in the U.S. rotate through a VA hospital at some point during their training. In 2015 alone, more than 43,000 residents received some or all of their clinical training through VA.1 Of the approximately 120 VAMCs that hold academic affiliations

with medical schools and residency training programs, several hold affiliations with multiple institutions, including VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. The West Roxbury campus is the home of VA Boston’s acute care hospital, where residents and fellows from Boston Medical Center (BMC), Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) train together. These are 3 of the largest medical training programs in Boston, though each provides a unique training experience for residents due to differences in patient population, faculty expertise, and hospital network affiliations (Table 1).

This diversity brings differences in cultural norms, institutional preferences, and educational expectations. Furthermore, residents from different programs who work together at VA Boston are often meeting one another for the first time, as opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration among these 3 training programs do not exist outside of VA. This training environment presents both an opportunity

and a challenge for medical educators: offering the best possible learning experience for physiciansin-training from multiple programs while providing the best possible care for U.S. veterans.

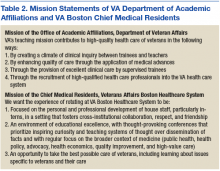

To guide educators charged with meeting this challenge, the VA Office of Academic Affiliations put forth a mission statement describing its overarching teaching mission (Table 2).2

To address this gap, chief medical residents from the 3 affiliate residency training programs came together to develop a shared mission statement for what we envision as the educational experience for all medical trainees rotating through VABHS (Table 2). In this article, we describe the development of a mission statement for graduate medical education in internal medicine at VABHS and provides examples of how our mission statement guided educational programming.

Methods

Whereas the affiliated institutions assign generic competency-based learning objectives to rotations at VABHS, no specific overarching educational objectives for residents have been defined previously. The directors of the internal medicine residency programs at each of the VABHS affiliate institutions grant their respective VA-based chief medical residents the autonomy to deliver graduate medical education at VA as they see fit, in collaboration with their colleagues from the other affiliated institutions and the VA director of medical resident education. This autonomy and flexibility allowed each of the chief medical residents to articulate an individual vision for VA graduate medical education based on their affiliate program’s goals, values, and mission.

At the beginning of the 2016/2017 academic year, in partnership with the director of medical resident education at VABHS, the chief medical residents met to reconcile these into a single shared mission statement. Special attention was paid to educational gaps at each affiliate institution that could be filled while residents were rotating at VABHS. Once all educational goals and priorities of the shared mission statement were identified, the chief medical residents and director of medical resident education adopted the mission statement as the blueprint for all educational programming for the academic year. Progress toward enacting the various components of the mission statement was reviewed monthly and changes in educational programming to ensure adequate emphasis of all components were made accordingly.

Results

Our first goal was to promote the personal and professional development of residents who rotate through VABHS, particularly interns, in a setting that fosters cross-institutional collaboration, respect, and friendship. The West Roxbury campus of VABHS is the only hospital in the city where internal medicine residents from 3 large training programs work together on teams that have been intentionally built to place residents from different institutions with one another. In educational conferences, we encouraged residents from different training programs to share their experiences with patient populations that others may not see at their home institutions, based on the specialized care that each institution provides. The conferences also give residents the opportunity to provide and receive near-peer teaching in a collegial environment.

Our second goal was to maintain an environment of educational excellence. We produced thought-provoking conferences that prioritized inspiring curiosity and teaching systems of thought over the dissemination of facts. We regularly focused on the broader context of medicine in case conferences and journal club, including topics such as public health, health policy, advocacy, health economics, quality improvement (QI), and high-value care. Our morning reports were interactive and participatory, emphasizing both technical skill practice and sophisticated clinical reasoning.

We embraced the principles of cognitive learning theory by priming learners with preconference “teasers” that previewed conference topics to be discussed. Every Friday, we played a medical version of Jeopardy!, which used spaced learning to consolidate the week’s teaching points in a fun, collaborative, and collegial atmosphere. Our dedicated patient safety conference gave residents the chance to use QI tools to dissect and tackle real problems in the hospital, and our monthly Morbidity and Mortality conference served as inspiration for many of the resident-driven QI projects.

Our third goal was to challenge physicians to provide the best possible care to veterans, including learning about issues unique to this often-marginalized population. We emphasized that training at a VA hospital is a privilege and that the best way to honor our veterans is to take advantage of the unique learning opportunities available at VA. To that end, we exposed residents to veteran-specific educational content, ranging from the structure and payment model of VHA to service-related medical conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, other mental health issues, traumatic brain injury, Agent Orange exposure, and Gulf War Syndrome.

Discussion

Findings from the recently published Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) 2016 Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) Report support the need for mission statements like ours to guide the delivery of graduate medical education.3 A major finding of this report was that the development and implementation of graduate medical education largely occurs separately from other areas of organizational and strategic focus within clinical learning environments. Our mission statement has served as a road map for aligning the delivery of graduate medical education at VABHS with the specific strengths of the clinical learning environment that VA affords.

Additionally, the 2016 CLER report identified a lack of specificity in training on health care disparities and cultural competency for the specific populations served by the surveyed residency programs. The emphasis we placed on learning about issues specific to the care of the veteran population highlights the potential for other mission statements like ours to bridge the gap between articulation and execution of educational priorities. Finally, through the academic partnerships it holds with more than 90% of medical schools in the U.S., VA already has an integral role in both undergraduate and graduate medical education that positions its hospitals as ideal training environments in which to address shortcomings in medical training like those identified by the ACGME.4

Conclusion

We propose this mission statement as a model for the delivery of graduate medical education throughout all VA hospitals with academic affiliations and especially those where trainees from multiple institutions work together. As embodied in our mission statement, our goal was to provide a clinical training experience at VA that complements that of our residents’ home institutions and fosters a respect for and interest in the special care provided at VA. The development of a shared mission statement provides an invaluable tool in accomplishing that goal. We encourage chief medical residents and other leaders in medical education in all specialties at VAMCs to develop their own mission statements that reflect and embody the values of each affiliated training program. For our residents, rotating at VA is an opportunity to learn the practice of medicine for veterans, rather than practicing medicine on veterans. It is our sincere hope that shaping our residents’ educational experience in this fashion will foster a greater appreciation for the care of our nation’s veterans.

1. VA Office of Academic Affiliations. 2015 statistics: health professions trainees. http://www.va.gov/oaa/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 18, 2017.

2. VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the Office of Academic Affiliations. http://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp. Updated June 23, 2017. Accessed September 18, 2017.

3. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Clinical learning environment review – national report of findings 2016 – executive summary. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/CLER/ACGME-CLER-ExecutiveSummary.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 18, 2017.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. The VA and academic medicine: partners in health care, training, and research. https://www.aamc.org/download/385612/data/07182014.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2017.

More than 65% of all physicians who train in the U.S. rotate through a VA hospital at some point during their training. In 2015 alone, more than 43,000 residents received some or all of their clinical training through VA.1 Of the approximately 120 VAMCs that hold academic affiliations

with medical schools and residency training programs, several hold affiliations with multiple institutions, including VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. The West Roxbury campus is the home of VA Boston’s acute care hospital, where residents and fellows from Boston Medical Center (BMC), Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) train together. These are 3 of the largest medical training programs in Boston, though each provides a unique training experience for residents due to differences in patient population, faculty expertise, and hospital network affiliations (Table 1).

This diversity brings differences in cultural norms, institutional preferences, and educational expectations. Furthermore, residents from different programs who work together at VA Boston are often meeting one another for the first time, as opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration among these 3 training programs do not exist outside of VA. This training environment presents both an opportunity

and a challenge for medical educators: offering the best possible learning experience for physiciansin-training from multiple programs while providing the best possible care for U.S. veterans.

To guide educators charged with meeting this challenge, the VA Office of Academic Affiliations put forth a mission statement describing its overarching teaching mission (Table 2).2

To address this gap, chief medical residents from the 3 affiliate residency training programs came together to develop a shared mission statement for what we envision as the educational experience for all medical trainees rotating through VABHS (Table 2). In this article, we describe the development of a mission statement for graduate medical education in internal medicine at VABHS and provides examples of how our mission statement guided educational programming.

Methods

Whereas the affiliated institutions assign generic competency-based learning objectives to rotations at VABHS, no specific overarching educational objectives for residents have been defined previously. The directors of the internal medicine residency programs at each of the VABHS affiliate institutions grant their respective VA-based chief medical residents the autonomy to deliver graduate medical education at VA as they see fit, in collaboration with their colleagues from the other affiliated institutions and the VA director of medical resident education. This autonomy and flexibility allowed each of the chief medical residents to articulate an individual vision for VA graduate medical education based on their affiliate program’s goals, values, and mission.

At the beginning of the 2016/2017 academic year, in partnership with the director of medical resident education at VABHS, the chief medical residents met to reconcile these into a single shared mission statement. Special attention was paid to educational gaps at each affiliate institution that could be filled while residents were rotating at VABHS. Once all educational goals and priorities of the shared mission statement were identified, the chief medical residents and director of medical resident education adopted the mission statement as the blueprint for all educational programming for the academic year. Progress toward enacting the various components of the mission statement was reviewed monthly and changes in educational programming to ensure adequate emphasis of all components were made accordingly.

Results

Our first goal was to promote the personal and professional development of residents who rotate through VABHS, particularly interns, in a setting that fosters cross-institutional collaboration, respect, and friendship. The West Roxbury campus of VABHS is the only hospital in the city where internal medicine residents from 3 large training programs work together on teams that have been intentionally built to place residents from different institutions with one another. In educational conferences, we encouraged residents from different training programs to share their experiences with patient populations that others may not see at their home institutions, based on the specialized care that each institution provides. The conferences also give residents the opportunity to provide and receive near-peer teaching in a collegial environment.

Our second goal was to maintain an environment of educational excellence. We produced thought-provoking conferences that prioritized inspiring curiosity and teaching systems of thought over the dissemination of facts. We regularly focused on the broader context of medicine in case conferences and journal club, including topics such as public health, health policy, advocacy, health economics, quality improvement (QI), and high-value care. Our morning reports were interactive and participatory, emphasizing both technical skill practice and sophisticated clinical reasoning.

We embraced the principles of cognitive learning theory by priming learners with preconference “teasers” that previewed conference topics to be discussed. Every Friday, we played a medical version of Jeopardy!, which used spaced learning to consolidate the week’s teaching points in a fun, collaborative, and collegial atmosphere. Our dedicated patient safety conference gave residents the chance to use QI tools to dissect and tackle real problems in the hospital, and our monthly Morbidity and Mortality conference served as inspiration for many of the resident-driven QI projects.

Our third goal was to challenge physicians to provide the best possible care to veterans, including learning about issues unique to this often-marginalized population. We emphasized that training at a VA hospital is a privilege and that the best way to honor our veterans is to take advantage of the unique learning opportunities available at VA. To that end, we exposed residents to veteran-specific educational content, ranging from the structure and payment model of VHA to service-related medical conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, other mental health issues, traumatic brain injury, Agent Orange exposure, and Gulf War Syndrome.

Discussion

Findings from the recently published Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) 2016 Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) Report support the need for mission statements like ours to guide the delivery of graduate medical education.3 A major finding of this report was that the development and implementation of graduate medical education largely occurs separately from other areas of organizational and strategic focus within clinical learning environments. Our mission statement has served as a road map for aligning the delivery of graduate medical education at VABHS with the specific strengths of the clinical learning environment that VA affords.

Additionally, the 2016 CLER report identified a lack of specificity in training on health care disparities and cultural competency for the specific populations served by the surveyed residency programs. The emphasis we placed on learning about issues specific to the care of the veteran population highlights the potential for other mission statements like ours to bridge the gap between articulation and execution of educational priorities. Finally, through the academic partnerships it holds with more than 90% of medical schools in the U.S., VA already has an integral role in both undergraduate and graduate medical education that positions its hospitals as ideal training environments in which to address shortcomings in medical training like those identified by the ACGME.4

Conclusion

We propose this mission statement as a model for the delivery of graduate medical education throughout all VA hospitals with academic affiliations and especially those where trainees from multiple institutions work together. As embodied in our mission statement, our goal was to provide a clinical training experience at VA that complements that of our residents’ home institutions and fosters a respect for and interest in the special care provided at VA. The development of a shared mission statement provides an invaluable tool in accomplishing that goal. We encourage chief medical residents and other leaders in medical education in all specialties at VAMCs to develop their own mission statements that reflect and embody the values of each affiliated training program. For our residents, rotating at VA is an opportunity to learn the practice of medicine for veterans, rather than practicing medicine on veterans. It is our sincere hope that shaping our residents’ educational experience in this fashion will foster a greater appreciation for the care of our nation’s veterans.

More than 65% of all physicians who train in the U.S. rotate through a VA hospital at some point during their training. In 2015 alone, more than 43,000 residents received some or all of their clinical training through VA.1 Of the approximately 120 VAMCs that hold academic affiliations

with medical schools and residency training programs, several hold affiliations with multiple institutions, including VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. The West Roxbury campus is the home of VA Boston’s acute care hospital, where residents and fellows from Boston Medical Center (BMC), Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) train together. These are 3 of the largest medical training programs in Boston, though each provides a unique training experience for residents due to differences in patient population, faculty expertise, and hospital network affiliations (Table 1).

This diversity brings differences in cultural norms, institutional preferences, and educational expectations. Furthermore, residents from different programs who work together at VA Boston are often meeting one another for the first time, as opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration among these 3 training programs do not exist outside of VA. This training environment presents both an opportunity

and a challenge for medical educators: offering the best possible learning experience for physiciansin-training from multiple programs while providing the best possible care for U.S. veterans.

To guide educators charged with meeting this challenge, the VA Office of Academic Affiliations put forth a mission statement describing its overarching teaching mission (Table 2).2

To address this gap, chief medical residents from the 3 affiliate residency training programs came together to develop a shared mission statement for what we envision as the educational experience for all medical trainees rotating through VABHS (Table 2). In this article, we describe the development of a mission statement for graduate medical education in internal medicine at VABHS and provides examples of how our mission statement guided educational programming.

Methods

Whereas the affiliated institutions assign generic competency-based learning objectives to rotations at VABHS, no specific overarching educational objectives for residents have been defined previously. The directors of the internal medicine residency programs at each of the VABHS affiliate institutions grant their respective VA-based chief medical residents the autonomy to deliver graduate medical education at VA as they see fit, in collaboration with their colleagues from the other affiliated institutions and the VA director of medical resident education. This autonomy and flexibility allowed each of the chief medical residents to articulate an individual vision for VA graduate medical education based on their affiliate program’s goals, values, and mission.

At the beginning of the 2016/2017 academic year, in partnership with the director of medical resident education at VABHS, the chief medical residents met to reconcile these into a single shared mission statement. Special attention was paid to educational gaps at each affiliate institution that could be filled while residents were rotating at VABHS. Once all educational goals and priorities of the shared mission statement were identified, the chief medical residents and director of medical resident education adopted the mission statement as the blueprint for all educational programming for the academic year. Progress toward enacting the various components of the mission statement was reviewed monthly and changes in educational programming to ensure adequate emphasis of all components were made accordingly.

Results

Our first goal was to promote the personal and professional development of residents who rotate through VABHS, particularly interns, in a setting that fosters cross-institutional collaboration, respect, and friendship. The West Roxbury campus of VABHS is the only hospital in the city where internal medicine residents from 3 large training programs work together on teams that have been intentionally built to place residents from different institutions with one another. In educational conferences, we encouraged residents from different training programs to share their experiences with patient populations that others may not see at their home institutions, based on the specialized care that each institution provides. The conferences also give residents the opportunity to provide and receive near-peer teaching in a collegial environment.

Our second goal was to maintain an environment of educational excellence. We produced thought-provoking conferences that prioritized inspiring curiosity and teaching systems of thought over the dissemination of facts. We regularly focused on the broader context of medicine in case conferences and journal club, including topics such as public health, health policy, advocacy, health economics, quality improvement (QI), and high-value care. Our morning reports were interactive and participatory, emphasizing both technical skill practice and sophisticated clinical reasoning.

We embraced the principles of cognitive learning theory by priming learners with preconference “teasers” that previewed conference topics to be discussed. Every Friday, we played a medical version of Jeopardy!, which used spaced learning to consolidate the week’s teaching points in a fun, collaborative, and collegial atmosphere. Our dedicated patient safety conference gave residents the chance to use QI tools to dissect and tackle real problems in the hospital, and our monthly Morbidity and Mortality conference served as inspiration for many of the resident-driven QI projects.

Our third goal was to challenge physicians to provide the best possible care to veterans, including learning about issues unique to this often-marginalized population. We emphasized that training at a VA hospital is a privilege and that the best way to honor our veterans is to take advantage of the unique learning opportunities available at VA. To that end, we exposed residents to veteran-specific educational content, ranging from the structure and payment model of VHA to service-related medical conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, other mental health issues, traumatic brain injury, Agent Orange exposure, and Gulf War Syndrome.

Discussion

Findings from the recently published Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) 2016 Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) Report support the need for mission statements like ours to guide the delivery of graduate medical education.3 A major finding of this report was that the development and implementation of graduate medical education largely occurs separately from other areas of organizational and strategic focus within clinical learning environments. Our mission statement has served as a road map for aligning the delivery of graduate medical education at VABHS with the specific strengths of the clinical learning environment that VA affords.

Additionally, the 2016 CLER report identified a lack of specificity in training on health care disparities and cultural competency for the specific populations served by the surveyed residency programs. The emphasis we placed on learning about issues specific to the care of the veteran population highlights the potential for other mission statements like ours to bridge the gap between articulation and execution of educational priorities. Finally, through the academic partnerships it holds with more than 90% of medical schools in the U.S., VA already has an integral role in both undergraduate and graduate medical education that positions its hospitals as ideal training environments in which to address shortcomings in medical training like those identified by the ACGME.4

Conclusion

We propose this mission statement as a model for the delivery of graduate medical education throughout all VA hospitals with academic affiliations and especially those where trainees from multiple institutions work together. As embodied in our mission statement, our goal was to provide a clinical training experience at VA that complements that of our residents’ home institutions and fosters a respect for and interest in the special care provided at VA. The development of a shared mission statement provides an invaluable tool in accomplishing that goal. We encourage chief medical residents and other leaders in medical education in all specialties at VAMCs to develop their own mission statements that reflect and embody the values of each affiliated training program. For our residents, rotating at VA is an opportunity to learn the practice of medicine for veterans, rather than practicing medicine on veterans. It is our sincere hope that shaping our residents’ educational experience in this fashion will foster a greater appreciation for the care of our nation’s veterans.

1. VA Office of Academic Affiliations. 2015 statistics: health professions trainees. http://www.va.gov/oaa/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 18, 2017.

2. VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the Office of Academic Affiliations. http://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp. Updated June 23, 2017. Accessed September 18, 2017.

3. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Clinical learning environment review – national report of findings 2016 – executive summary. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/CLER/ACGME-CLER-ExecutiveSummary.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 18, 2017.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. The VA and academic medicine: partners in health care, training, and research. https://www.aamc.org/download/385612/data/07182014.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2017.

1. VA Office of Academic Affiliations. 2015 statistics: health professions trainees. http://www.va.gov/oaa/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 18, 2017.

2. VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the Office of Academic Affiliations. http://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp. Updated June 23, 2017. Accessed September 18, 2017.

3. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Clinical learning environment review – national report of findings 2016 – executive summary. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/CLER/ACGME-CLER-ExecutiveSummary.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 18, 2017.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. The VA and academic medicine: partners in health care, training, and research. https://www.aamc.org/download/385612/data/07182014.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2017.