User login

What clinicians need to know about treating opioid use disorder

Communities across the United States have experienced a near-epidemic of opioid abuse. Deaths from opioid overdose have doubled since 2000 and increased 14% from 2013 to 2014.1 Treatment strategies for opioid use disorder (OUD) target individual well-being with the goal of preventing relapse. Most treatment approaches help patients gain self-confidence and have been described by patients as “giving them their life back.”

Broadly, the major phases of treatment for OUD are similar to those for other substance use disorders, and involve acute detoxification followed by long-term maintenance of sobriety. There are 3 main phases of treatment for OUD:

- treatment engagement

- stabilization and harm reduction

- sustained abstinence.

Long-term maintenance of sobriety in OUD could involve medications that are FDA-approved for this indication: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Psychosocial interventions can be used individually and in combination with pharmacotherapy. Because OUD is a chronic disorder typically characterized by intermittent relapse, patients could move back and forth between the different phases of treatment.

In this article, we highlight the medication and non-medication treatment options for the long-term management of OUD.

Defining abuseExogenous opioids are synthetic substances used for their analgesic and morphine-like properties. Opioids are indicated for the treatment of certain pain conditions and exist in varying potencies and delivery systems, which are tailored for specific types of pain.2 Opioids work through activity at opioid receptors found in the brain, spinal cord, gut, and other organs. Agonism of specific opioid receptors results in a decreased perception of pain and contributes to their abuse potential.

Because of their abuse potential, prescription of opioids is governed by the Controlled Substances Act3 of the United States. Despite these regulations, approximately 4.5% of U.S. adults from a nationally representative sample were found to be misusing prescription opioids.4 Another study used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and showed an increasing prevalence of OUD involving prescription drugs and resulting in increased mortality.5 The mortality rate from prescription opioids was found to be higher than for all other illicit drugs combined in 2013.6 Recently, Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which is intended to address the opioid crisis by expanding access to treatments for opioid overdose and addiction treatment services.7

The term “opioid use disorder” is found in DSM-58 and replaces the previous diagnoses of opioid abuse and dependence in DSM-IV-TR.9 OUD is characterized by a strong desire to continue using opioids despite problems associated with their use. Patients with OUD often experience cravings for opioids, tolerance, repeated failures at cutting down or limiting use, and decreased involvement in social activities.

Maladaptive use of opioids can result in physiologic dependence and lead to withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, drug craving, insomnia, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, diarrhea, and piloerection. However, physiologic dependence might not necessarily lead to development of OUD, which can be diagnosed when enough other diagnostic criteria present in the absence of physiologic dependence.

Misuse of prescription opioids is more prevalent among patients who meet criteria for other substance use disorders than among patients who do not.10 Misuse of prescription opioids often results in greater health care utilization, including the need for emergency services, hospitalization, and detoxification.

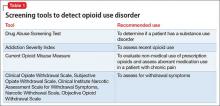

Assessing for OUDThe Addiction Severity Index was designed to classify and monitor misuse of opioids. The Index has poor sensitivity; it detects recent opioid use but fails to differentiate patients using prescribed opioids from those who are abusing opioids.11 By comparison, the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) was developed to monitor opioid use in chemical dependency treatment settings.12 The COMM has reliable internal consistency13 and validity and can be used to assess use of opioids outside of routine medical care. To gauge the severity of withdrawal symptoms, the Objective Opioid Withdrawal Scale or Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale14 can be used. Table 1 summarizes some standardized tools used to assess OUD.

Neurobiological considerationsOpioids work through activity at mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors. These receptors are present in both the peripheral and the central nervous system. Exogenous opioids work through activity at G protein-coupled receptors and by activating specific neurotransmitter systems. The effect of a given opioid drug is dependent on the type and location of receptors it modulates and can range from CNS depression to euphoria.

For example, mu receptor activation produces sedation, euphoria, or analgesia depending upon the location, frequency, and duration of receptor occupancy. Activation of CNS mu receptors can cause miosis and respiratory depression, whereas mu receptor activation in the peripheral nervous system can cause constipation and cough suppression. Mu receptor stimulation through various G-proteins triggers the second messenger cascade, generating enzymes such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

Clinical considerationsTreating OUD is challenging because of the ease with which patients can obtain opioids and because sometimes OUD occurs iatrogenically. Engaging patients in treatment is an important step in recovery, but it does not necessarily lead to reduction in opioid use. The engagement stage can involve outreach workers to encourage further treatment. Developing a therapeutic alliance and appropriately incentivizing patients also promotes entry into treatment. Motivational interviewing is used often in substance use treatment programs and can help engage patients in treatment and evaluate their willingness to change problematic behaviors.

Managing acute withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms usually are not life threatening, but can be in the context of other medical conditions, such as autonomic instability, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and dehydration. Withdrawal symptoms also can be life-threatening during in utero exposure to a fetus. Pharmacotherapeutic options to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms include long-acting opioids, such as methadone and buprenorphine,15 which can be administered in an ambulatory setting. The combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also can be used to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms.

The alpha-2 agonist16 clonidine, although not FDA-approved for OUD or opioid withdrawal, could be used to shorten the duration of withdrawal symptoms. Clonidine also decreases methadone withdrawal and can be combined with naloxone to target naloxone-induced opioid withdrawal symptoms.17,18 Nalbuphine and butorphanol should be avoided during opioid withdrawal because they antagonize opioid receptors and can precipitate withdrawal symptoms.19,20

Maintenance phase involves long-term stabilization and relapse prevention. Treatment options include medication and non-medication interventions.21

Non-pharmacologic treatment options,22 principally psychosocial interventions, can be used on their own or in combination with medications for maintenance treatment of OUD. Psychosocial interventions include structured, professionally administered interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), aversion therapy, and day-treatment programs. Interventions such as peer counseling and self-help groups also are considered psychosocial interventions, but do not require the same type of professional training.

Peer support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA) help members achieve and maintain sobriety and often focus on a traditional 12-step format or on the more recent Matrix Model,23,24 which is an intensive outpatient treatment program based on components of relapse prevention, motivational interviewing, CBT, and psychoeducation.

In these peer support models, group members discuss patterns of substance use and help one another recognize and overcome problematic behaviors. Groups may vary in terms of their specific approach. For example, NA encourages group members to focus on addiction itself while Methadone Anonymous prefers participants also discuss pharmacologic treatment experiences. Additional services for finding housing and assisting with job placement are also part of some relapse prevention strategies.

Although studies on the use of abstinence-based treatments are limited, abstinence-based therapy is an option for patients wishing to undergo chemical dependency treatment without taking prescription medications to address cravings or withdrawal symptoms.25 However, abstinence-based treatments have been shown to be less effective in improving outcomes than medication-assisted treatment (MAT).26 MAT combines medications and behavioral therapies for treating substance use disorders.

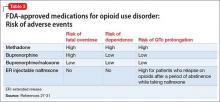

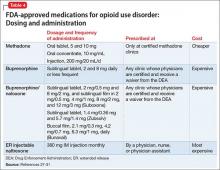

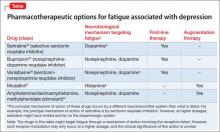

Pharmacologically, OUD can be treated with opioid agonist and antagonist medications. As summarized in Tables 2-4,27-31 these medications differ based on their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activity at mu opioid receptors. Opioid system agonists, such as methadone and buprenorphine, decrease cravings by mimicking the activity of exogenous opioids. The opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone reinforce abstinence by inhibiting the euphoric effects associated with opioid use. The medication of choice for a given patient depends on:

- treatment adherence

- clinical setting

- degree of withdrawal symptoms

- motivation.26

If a patient is actively seeking abstinence from opioids, either agonist or antagonist treatment can be used. In cases where a patient is not seeking abstinence, then preference should be given to opioid agonists to prevent overdose.26

Evidence suggests MAT can improve outcomes with OUD when compared with abstinence treatment alone. Several randomized, controlled, trials showed methadone and buprenorphine were more effective at treating OUD compared with treatment without medication. To date, 3 medications have been FDA-approved for treating OUD: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.26 All 3 medications differ in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activities at central mu-opioid receptor, as summarized in Tables 2-4.27-31

MethadoneMethadone reduces the euphoric effects of opioid use because it binds to and blocks opioid receptors. Methadone is an opioid replacement strategy; higher dosages are used for maintenance treatment to prevent additional dosages of opioids from causing euphoria. Methadone typically is administered once daily. However, in certain circumstances, such as rapid metabolism or pregnancy, it can be given as a twice-daily dosing regimen. Specific ABCB1 variants and DRD2 genetic polymorphisms (simultaneous occurrence of ≥2 genetically determined phenotypes) might determine the dosage requirements of methadone.32

Methadone during pregnancy. Methadone is the treatment of choice for opioid-dependent women during pregnancy33 and is listed as pregnancy category C because it can result in physiologic dependence of the newborn, although there are no documented controlled studies in humans to assess this risk. Methadone can be used while breast-feeding as long as patients are HIV-negative and not abusing other drugs.34,35 Because the methadone concentration in breast milk generally is low, the medication can be administered to nursing mothers after a careful consideration of risks and benefits.

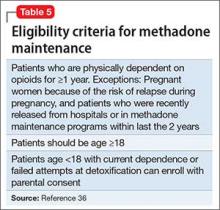

Methadone administration. There are stringent eligibility criteria for methadone administration; not all physicians are authorized to prescribe methadone. Its use is federally regulated and only licensed treatment programs and licensed inpatient detoxification units can prescribe and dispense methadone in controlled settings and under the direct supervision of clinical personnel (Table 5).36 Patients meeting eligibility criteria can attend a specialized methadone clinic.

One of the challenges when using methadone for long-term management of OUD is tapering the dosage and attempting to discontinue the medication. Discontinuation of methadone leads to withdrawal symptoms and requires a carefully tailored tapering schedule. The literature on methadone tapering is limited. Tapering schedules could differ from practice to practice and, in many cases, are highly individualized based on the need and response of specific patients.

Dosage reduction schedules can last from 2 to 3 weeks to 6 months. Studies indicate rapid reduction worsens treatment outcomes and protracted tapering is associated with better outcomes. A suggested tapering schedule could involve decreasing the dosage by 20% to 25% until reaching a dosage of 30 mg/d, then decreasing by 5 mg/d every 3 to 5 days until reaching a dosage of 10 mg/d, before finally decreasing by 2.5 mg/d every 3 to 5 days.

Some randomized trials have shown better outcomes with long-term treatment. The goal of many programs is transitioning from maintenance treatment to abstinence. However, programs targeting maintenance rather than abstinence have been shown to be more effective.

The FDA has no defined limits for treatment duration with either methadone or buprenorphine. Therefore, the decision to taper or discontinue either medication should be made carefully case by case, using sound clinical judgment. Studies show that methadone treatment could reduce the spread of HIV,37,38 decrease criminal behaviors,39 and reduce overall mortality rates.40 A follow-up study comparing individuals randomly assigned to receive methadone or buprenorphine for OUD showed reduced risk of mortality overall40 in both groups.

Adverse events reported during treatment with methadone include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, constipation, drowsiness, QTc prolongation, and torsade de pointes.41 Therefore, the FDA recommends obtaining a detailed medical history and baseline electrocardiogram (ECG), with a repeat ECG within the first month of treatment and then annually. Informing patients about the possibility of arrhythmias is part of the informed consent process before starting methadone.

Clinicians also should be vigilant when using methadone in combination with other medications that can prolong the QTc interval (eg, some antipsychotics). Methadone has a greater risk of fatal overdose then buprenorphine. A large-scale study of >16,000 patients reported a 4-fold increase in mortality resulting from methadone overdose compared with buprenorphine.42

BuprenorphineBuprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist at the mu opioid receptor. A full opioid agonist binds and fully activates the opioid receptors; an antagonist blocks the same. An opioid receptor partial agonist partially activates the receptor. Therefore, an opioid system partial agonist is a functional antagonist and, at lower dosages, has weak agonist effects; at higher dosages, a partial agonist antagonizes other endogenous and exogenous opioids that compete for binding at the same receptor.43 Because of the partial agonist effect, buprenorphine could result in less physical dependence and less withdrawal symptoms.

Administration. In contrast to methadone, buprenorphine can be prescribed by physicians for long-term management of OUD in the United States. Buprenorphine is available in 2 formulations: a sublingual form for daily use and a long-acting form that causes less withdrawal symptoms and cravings. In May 2016 the FDA approved the first buprenorphine implant for use in opioid dependence.44,45

To prevent withdrawal symptoms, a 24-hour period of opioid abstinence is recommended before starting buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone treatment.46 Although lacking empirical evidence, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors, such as entacapone, have an anti-craving affect and are used by some clinicians to improve adherence with buprenorphine. This is because of their ability to balance dopamine, which is central to the reward pathway responsible for cravings. Although use of COMT inhibitors might make sense intuitively, such use is off-label and should be based on clinical judgment and a review of the available literature. A study showed that tapering buprenorphine for 4 weeks in combination with naltrexone improved the abstinence rate.47

Adverse effects. Some of the adverse events reported during treatment with buprenorphine include fever, back pain, nausea, cough, sedation, difficulty with urination, and constipation. Respiratory depression is a less common effect of buprenorphine, compared with full opioid agonists, because of the medication’s mechanism of action as a partial agonist.48 As a result, buprenorphine has been shown to have a lower risk of fatal overdose than methadone.49 Studies have shown buprenorphine to be more likely than methadone to reduce neonatal abstinence syndromes.50

NaltrexoneNaltrexone is an opioid antagonist and is an option to promote relapse prevention. Because of its antagonist properties, naltrexone treatment should always start after opioid detoxification because it can potentiate immediate withdrawal symptoms. Naltrexone is available in oral and long-acting formulations, the latter of which may be considered in patients who have difficulty with adherence.37

Oral naltrexone is taken as a single 50 mg-tablet once daily, whereas dosing for long-acting naltrexone in injectable and implantable formulations varies. These long-acting naltrexone formulations typically are administered monthly. Some of the adverse events reported during treatment with naltrexone are nausea, liver damage, and injection site pain.51

Buprenorphine/naloxoneBecause of buprenorphine’s agonist effects, it has a relatively high abuse potential compared with other opioids.52 Naloxone, on the other hand, is an opioid antagonist and is poorly absorbed when given orally and is associated with withdrawal symptoms if used intravenously. Therefore, naloxone is added to buprenorphine to decrease the likelihood of abuse when both are used as a combination product.53

Buprenorphine is combined with naloxone in a ratio of 4:1. Induction begins by using a 2 mg/0.5 mg tablet with dosage titration until symptoms abate. A combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also is available in film and tablet formulations. Patients must abstain from other opioids for at least 24 hours before initiating buprenorphine/naloxone treatment to prevent the precipitation of withdrawal symptoms.

1. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

2. Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1695-1700.

3. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

4. Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, et al. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1-3):38-47.

5. Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468-1478.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, 2014. Multiple cause of death data. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

7. Twachtman G. Congress sends opioid legislation to the President. Clinical Psychiatry News. http://www.clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/?id=2407&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=524025&cHash=e93d5d1f86d20e53d3e2d8b07e9562b2. Published July 15, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

10. McCabe SE, Cranford JA, West BT. Trends in prescription drug abuse and dependence, co-occurrence with other substance use disorders, and treatment utilization: results from two national surveys. Addict Behav. 2008;33(10):1297-1305.

11. Butler SF, Villapiano A, Malinow A. The effect of computer-mediated administration on self-disclosure of problems on the Addiction Severity Index. J Addict Med. 2009;3(4):194-203.

12. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152(2):397-402.

13. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(9):770-776.

14. Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253-259.

15. Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Clinical practice. Office-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):817-823.

16. Gowing LR, Farrell M, Ali RL, et al. α2‐Adrenergic agonists in opioid withdrawal. Addiction. 2002;97(1):49-58.

17. Loimer N, Hofmann P, Chaudhry H. Ultrashort noninvasive opiate detoxification. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):839.

18. Charney DS, Sternberg DE, Kleber HD, et al. The clinical use of clonidine in abrupt withdrawal from methadone. Effects on blood pressure and specific signs and symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(11):1273-1277.

19. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Antagonist effects of nalbuphine in opioid-dependent human volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248(3):929-937.

20. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Discrimination of butorphanol and nalbuphine in opioid-dependent humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;37(3):511-522.

21. Effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. National Consensus Development Panel on Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate Addiction. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1936-1943.

22. Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli, M, et al. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD004147. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub4.

23. Obert JL, McCann MJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al. The matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: history and description. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(2):157-164.

24. Mayet S, Farrell M, Ferri M, et al. Psychosocial treatment for opiate abuse and dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004330.

25. McAuliffe WE. A randomized controlled trial of recovery training and self-help for opioid addicts in New England and Hong Kong. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1990;22(2):197-209.

26. Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):63-75.

27. Gibson AE, Degenhardt LJ. Mortality related to pharmacotherapies for opioid dependence: a comparative analysis of coronial records. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:405-410.

28. Clark L, Haram E, Johnson K, et al. Getting started with medication-assisted treatment with lessons from advancing recovery. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2010.

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Vivitrol (naltrexone for extended-release injectable suspension): NDA 21-897C—Briefing document/background package. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/Psychopharmacologic DrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM225664.pdf. Published September 16, 2010. Accessed July 11, 2016.

30. Providers Clinical Support System. PCSS Guidance. Buprenorphine induction. http://pcssmat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/PCSS-MATGuidanceBuprenorphineInduction.Casadonte.pdf. Updated November 27, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2016.

31. An introduction to extended-release injectable naltrexone for the treatment of people with opioid dependence. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4682.

32. Doehring A, von Hentig N, Graff J, et al. Genetic variants altering dopamine D2 receptor expression or function modulate the risk of opiate addiction and the dosage requirements of methadone substitution. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19(6):407-414.

33. Mitchell JL. Pregnant, substance-abusing women: treatment improvement protocol (TIP) Series 2. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1993. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 95-3056.

34. McCarthy JJ, Posey BL. Methadone levels in human milk. J Hum Lact. 2000;16(2):115-120.

35. Geraghty B, Graham EA, Logan B, et al. Methadone levels in breast milk. J Hum Lact. 1997;13(3):227-230.

36. Krambeer LL, von McKnelly W Jr, Gabrielli WF Jr, et al. Methadone therapy for opioid dependence. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(12):2404-2410.

37. Novick DM, Joseph H, Croxson TS, et al. Absence of antibody to human immunodeficiency virus in long-term, socially rehabilitated methadone maintenance patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(1):97-99.

38. Gowing LR, Farrell M, Bornemann R, et al. Brief report: methadone treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):193-195.

39. Nurco DN, Ball JC, Shaffer JW, et al. The criminality of narcotic addicts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(2):94-102.

40. Gibson A, Degenhardt L, Mattick RP, et al. Exposure to opioid maintenance treatment reduces long-term mortality. Addiction. 2008;103(3):462-468.

41. Pearson EC, Woosley RL. QT prolongation and torsades de pointes among methadone users: reports to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(11):747-753.

42. Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, et al. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1-2):73-77.

43. Bickel WK, Amass L. Buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: a review. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;3(4):477-489.

44. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first buprenorphine implant for treatment of opioid dependence. http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm503719.htm. Published May 26, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

45. The National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment. https://www.naabt.org/index.cfm. Accessed July 18, 2016.

46. Buprenorphine: an alternative to methadone. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2003;45(1150):13-15.

47. Sigmon SC, Dunn KE, Saulsgiver K, et al. A randomized, double-blind evaluation of buprenorphine taper duration in primary prescription opioid abusers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1347-1354.

48. Dahan A, Yassen A, Bijl H, et al. Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(6):825-834.

49. Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, et al. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1-2):73-77.

50. Kakko J, Heilig M, Sarman I. Buprenorphine and methadone treatment of opiate dependence during pregnancy: comparison of fetal growth and neonatal outcomes in two consecutive case series. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(1-2):69-78.

51. Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, Kosten TR. Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(11):1727-1740.

52. Robinson GM, Dukes PD, Robinson BJ, et al. The misuse of buprenorphine and a buprenorphine-naloxone combination in Wellington, New Zealand. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33(1):81-86.

53. Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al; Buprenorphine/Naloxone Collaborative Study Group. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):949-958.

Communities across the United States have experienced a near-epidemic of opioid abuse. Deaths from opioid overdose have doubled since 2000 and increased 14% from 2013 to 2014.1 Treatment strategies for opioid use disorder (OUD) target individual well-being with the goal of preventing relapse. Most treatment approaches help patients gain self-confidence and have been described by patients as “giving them their life back.”

Broadly, the major phases of treatment for OUD are similar to those for other substance use disorders, and involve acute detoxification followed by long-term maintenance of sobriety. There are 3 main phases of treatment for OUD:

- treatment engagement

- stabilization and harm reduction

- sustained abstinence.

Long-term maintenance of sobriety in OUD could involve medications that are FDA-approved for this indication: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Psychosocial interventions can be used individually and in combination with pharmacotherapy. Because OUD is a chronic disorder typically characterized by intermittent relapse, patients could move back and forth between the different phases of treatment.

In this article, we highlight the medication and non-medication treatment options for the long-term management of OUD.

Defining abuseExogenous opioids are synthetic substances used for their analgesic and morphine-like properties. Opioids are indicated for the treatment of certain pain conditions and exist in varying potencies and delivery systems, which are tailored for specific types of pain.2 Opioids work through activity at opioid receptors found in the brain, spinal cord, gut, and other organs. Agonism of specific opioid receptors results in a decreased perception of pain and contributes to their abuse potential.

Because of their abuse potential, prescription of opioids is governed by the Controlled Substances Act3 of the United States. Despite these regulations, approximately 4.5% of U.S. adults from a nationally representative sample were found to be misusing prescription opioids.4 Another study used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and showed an increasing prevalence of OUD involving prescription drugs and resulting in increased mortality.5 The mortality rate from prescription opioids was found to be higher than for all other illicit drugs combined in 2013.6 Recently, Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which is intended to address the opioid crisis by expanding access to treatments for opioid overdose and addiction treatment services.7

The term “opioid use disorder” is found in DSM-58 and replaces the previous diagnoses of opioid abuse and dependence in DSM-IV-TR.9 OUD is characterized by a strong desire to continue using opioids despite problems associated with their use. Patients with OUD often experience cravings for opioids, tolerance, repeated failures at cutting down or limiting use, and decreased involvement in social activities.

Maladaptive use of opioids can result in physiologic dependence and lead to withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, drug craving, insomnia, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, diarrhea, and piloerection. However, physiologic dependence might not necessarily lead to development of OUD, which can be diagnosed when enough other diagnostic criteria present in the absence of physiologic dependence.

Misuse of prescription opioids is more prevalent among patients who meet criteria for other substance use disorders than among patients who do not.10 Misuse of prescription opioids often results in greater health care utilization, including the need for emergency services, hospitalization, and detoxification.

Assessing for OUDThe Addiction Severity Index was designed to classify and monitor misuse of opioids. The Index has poor sensitivity; it detects recent opioid use but fails to differentiate patients using prescribed opioids from those who are abusing opioids.11 By comparison, the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) was developed to monitor opioid use in chemical dependency treatment settings.12 The COMM has reliable internal consistency13 and validity and can be used to assess use of opioids outside of routine medical care. To gauge the severity of withdrawal symptoms, the Objective Opioid Withdrawal Scale or Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale14 can be used. Table 1 summarizes some standardized tools used to assess OUD.

Neurobiological considerationsOpioids work through activity at mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors. These receptors are present in both the peripheral and the central nervous system. Exogenous opioids work through activity at G protein-coupled receptors and by activating specific neurotransmitter systems. The effect of a given opioid drug is dependent on the type and location of receptors it modulates and can range from CNS depression to euphoria.

For example, mu receptor activation produces sedation, euphoria, or analgesia depending upon the location, frequency, and duration of receptor occupancy. Activation of CNS mu receptors can cause miosis and respiratory depression, whereas mu receptor activation in the peripheral nervous system can cause constipation and cough suppression. Mu receptor stimulation through various G-proteins triggers the second messenger cascade, generating enzymes such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

Clinical considerationsTreating OUD is challenging because of the ease with which patients can obtain opioids and because sometimes OUD occurs iatrogenically. Engaging patients in treatment is an important step in recovery, but it does not necessarily lead to reduction in opioid use. The engagement stage can involve outreach workers to encourage further treatment. Developing a therapeutic alliance and appropriately incentivizing patients also promotes entry into treatment. Motivational interviewing is used often in substance use treatment programs and can help engage patients in treatment and evaluate their willingness to change problematic behaviors.

Managing acute withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms usually are not life threatening, but can be in the context of other medical conditions, such as autonomic instability, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and dehydration. Withdrawal symptoms also can be life-threatening during in utero exposure to a fetus. Pharmacotherapeutic options to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms include long-acting opioids, such as methadone and buprenorphine,15 which can be administered in an ambulatory setting. The combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also can be used to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms.

The alpha-2 agonist16 clonidine, although not FDA-approved for OUD or opioid withdrawal, could be used to shorten the duration of withdrawal symptoms. Clonidine also decreases methadone withdrawal and can be combined with naloxone to target naloxone-induced opioid withdrawal symptoms.17,18 Nalbuphine and butorphanol should be avoided during opioid withdrawal because they antagonize opioid receptors and can precipitate withdrawal symptoms.19,20

Maintenance phase involves long-term stabilization and relapse prevention. Treatment options include medication and non-medication interventions.21

Non-pharmacologic treatment options,22 principally psychosocial interventions, can be used on their own or in combination with medications for maintenance treatment of OUD. Psychosocial interventions include structured, professionally administered interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), aversion therapy, and day-treatment programs. Interventions such as peer counseling and self-help groups also are considered psychosocial interventions, but do not require the same type of professional training.

Peer support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA) help members achieve and maintain sobriety and often focus on a traditional 12-step format or on the more recent Matrix Model,23,24 which is an intensive outpatient treatment program based on components of relapse prevention, motivational interviewing, CBT, and psychoeducation.

In these peer support models, group members discuss patterns of substance use and help one another recognize and overcome problematic behaviors. Groups may vary in terms of their specific approach. For example, NA encourages group members to focus on addiction itself while Methadone Anonymous prefers participants also discuss pharmacologic treatment experiences. Additional services for finding housing and assisting with job placement are also part of some relapse prevention strategies.

Although studies on the use of abstinence-based treatments are limited, abstinence-based therapy is an option for patients wishing to undergo chemical dependency treatment without taking prescription medications to address cravings or withdrawal symptoms.25 However, abstinence-based treatments have been shown to be less effective in improving outcomes than medication-assisted treatment (MAT).26 MAT combines medications and behavioral therapies for treating substance use disorders.

Pharmacologically, OUD can be treated with opioid agonist and antagonist medications. As summarized in Tables 2-4,27-31 these medications differ based on their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activity at mu opioid receptors. Opioid system agonists, such as methadone and buprenorphine, decrease cravings by mimicking the activity of exogenous opioids. The opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone reinforce abstinence by inhibiting the euphoric effects associated with opioid use. The medication of choice for a given patient depends on:

- treatment adherence

- clinical setting

- degree of withdrawal symptoms

- motivation.26

If a patient is actively seeking abstinence from opioids, either agonist or antagonist treatment can be used. In cases where a patient is not seeking abstinence, then preference should be given to opioid agonists to prevent overdose.26

Evidence suggests MAT can improve outcomes with OUD when compared with abstinence treatment alone. Several randomized, controlled, trials showed methadone and buprenorphine were more effective at treating OUD compared with treatment without medication. To date, 3 medications have been FDA-approved for treating OUD: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.26 All 3 medications differ in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activities at central mu-opioid receptor, as summarized in Tables 2-4.27-31

MethadoneMethadone reduces the euphoric effects of opioid use because it binds to and blocks opioid receptors. Methadone is an opioid replacement strategy; higher dosages are used for maintenance treatment to prevent additional dosages of opioids from causing euphoria. Methadone typically is administered once daily. However, in certain circumstances, such as rapid metabolism or pregnancy, it can be given as a twice-daily dosing regimen. Specific ABCB1 variants and DRD2 genetic polymorphisms (simultaneous occurrence of ≥2 genetically determined phenotypes) might determine the dosage requirements of methadone.32

Methadone during pregnancy. Methadone is the treatment of choice for opioid-dependent women during pregnancy33 and is listed as pregnancy category C because it can result in physiologic dependence of the newborn, although there are no documented controlled studies in humans to assess this risk. Methadone can be used while breast-feeding as long as patients are HIV-negative and not abusing other drugs.34,35 Because the methadone concentration in breast milk generally is low, the medication can be administered to nursing mothers after a careful consideration of risks and benefits.

Methadone administration. There are stringent eligibility criteria for methadone administration; not all physicians are authorized to prescribe methadone. Its use is federally regulated and only licensed treatment programs and licensed inpatient detoxification units can prescribe and dispense methadone in controlled settings and under the direct supervision of clinical personnel (Table 5).36 Patients meeting eligibility criteria can attend a specialized methadone clinic.

One of the challenges when using methadone for long-term management of OUD is tapering the dosage and attempting to discontinue the medication. Discontinuation of methadone leads to withdrawal symptoms and requires a carefully tailored tapering schedule. The literature on methadone tapering is limited. Tapering schedules could differ from practice to practice and, in many cases, are highly individualized based on the need and response of specific patients.

Dosage reduction schedules can last from 2 to 3 weeks to 6 months. Studies indicate rapid reduction worsens treatment outcomes and protracted tapering is associated with better outcomes. A suggested tapering schedule could involve decreasing the dosage by 20% to 25% until reaching a dosage of 30 mg/d, then decreasing by 5 mg/d every 3 to 5 days until reaching a dosage of 10 mg/d, before finally decreasing by 2.5 mg/d every 3 to 5 days.

Some randomized trials have shown better outcomes with long-term treatment. The goal of many programs is transitioning from maintenance treatment to abstinence. However, programs targeting maintenance rather than abstinence have been shown to be more effective.

The FDA has no defined limits for treatment duration with either methadone or buprenorphine. Therefore, the decision to taper or discontinue either medication should be made carefully case by case, using sound clinical judgment. Studies show that methadone treatment could reduce the spread of HIV,37,38 decrease criminal behaviors,39 and reduce overall mortality rates.40 A follow-up study comparing individuals randomly assigned to receive methadone or buprenorphine for OUD showed reduced risk of mortality overall40 in both groups.

Adverse events reported during treatment with methadone include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, constipation, drowsiness, QTc prolongation, and torsade de pointes.41 Therefore, the FDA recommends obtaining a detailed medical history and baseline electrocardiogram (ECG), with a repeat ECG within the first month of treatment and then annually. Informing patients about the possibility of arrhythmias is part of the informed consent process before starting methadone.

Clinicians also should be vigilant when using methadone in combination with other medications that can prolong the QTc interval (eg, some antipsychotics). Methadone has a greater risk of fatal overdose then buprenorphine. A large-scale study of >16,000 patients reported a 4-fold increase in mortality resulting from methadone overdose compared with buprenorphine.42

BuprenorphineBuprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist at the mu opioid receptor. A full opioid agonist binds and fully activates the opioid receptors; an antagonist blocks the same. An opioid receptor partial agonist partially activates the receptor. Therefore, an opioid system partial agonist is a functional antagonist and, at lower dosages, has weak agonist effects; at higher dosages, a partial agonist antagonizes other endogenous and exogenous opioids that compete for binding at the same receptor.43 Because of the partial agonist effect, buprenorphine could result in less physical dependence and less withdrawal symptoms.

Administration. In contrast to methadone, buprenorphine can be prescribed by physicians for long-term management of OUD in the United States. Buprenorphine is available in 2 formulations: a sublingual form for daily use and a long-acting form that causes less withdrawal symptoms and cravings. In May 2016 the FDA approved the first buprenorphine implant for use in opioid dependence.44,45

To prevent withdrawal symptoms, a 24-hour period of opioid abstinence is recommended before starting buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone treatment.46 Although lacking empirical evidence, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors, such as entacapone, have an anti-craving affect and are used by some clinicians to improve adherence with buprenorphine. This is because of their ability to balance dopamine, which is central to the reward pathway responsible for cravings. Although use of COMT inhibitors might make sense intuitively, such use is off-label and should be based on clinical judgment and a review of the available literature. A study showed that tapering buprenorphine for 4 weeks in combination with naltrexone improved the abstinence rate.47

Adverse effects. Some of the adverse events reported during treatment with buprenorphine include fever, back pain, nausea, cough, sedation, difficulty with urination, and constipation. Respiratory depression is a less common effect of buprenorphine, compared with full opioid agonists, because of the medication’s mechanism of action as a partial agonist.48 As a result, buprenorphine has been shown to have a lower risk of fatal overdose than methadone.49 Studies have shown buprenorphine to be more likely than methadone to reduce neonatal abstinence syndromes.50

NaltrexoneNaltrexone is an opioid antagonist and is an option to promote relapse prevention. Because of its antagonist properties, naltrexone treatment should always start after opioid detoxification because it can potentiate immediate withdrawal symptoms. Naltrexone is available in oral and long-acting formulations, the latter of which may be considered in patients who have difficulty with adherence.37

Oral naltrexone is taken as a single 50 mg-tablet once daily, whereas dosing for long-acting naltrexone in injectable and implantable formulations varies. These long-acting naltrexone formulations typically are administered monthly. Some of the adverse events reported during treatment with naltrexone are nausea, liver damage, and injection site pain.51

Buprenorphine/naloxoneBecause of buprenorphine’s agonist effects, it has a relatively high abuse potential compared with other opioids.52 Naloxone, on the other hand, is an opioid antagonist and is poorly absorbed when given orally and is associated with withdrawal symptoms if used intravenously. Therefore, naloxone is added to buprenorphine to decrease the likelihood of abuse when both are used as a combination product.53

Buprenorphine is combined with naloxone in a ratio of 4:1. Induction begins by using a 2 mg/0.5 mg tablet with dosage titration until symptoms abate. A combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also is available in film and tablet formulations. Patients must abstain from other opioids for at least 24 hours before initiating buprenorphine/naloxone treatment to prevent the precipitation of withdrawal symptoms.

Communities across the United States have experienced a near-epidemic of opioid abuse. Deaths from opioid overdose have doubled since 2000 and increased 14% from 2013 to 2014.1 Treatment strategies for opioid use disorder (OUD) target individual well-being with the goal of preventing relapse. Most treatment approaches help patients gain self-confidence and have been described by patients as “giving them their life back.”

Broadly, the major phases of treatment for OUD are similar to those for other substance use disorders, and involve acute detoxification followed by long-term maintenance of sobriety. There are 3 main phases of treatment for OUD:

- treatment engagement

- stabilization and harm reduction

- sustained abstinence.

Long-term maintenance of sobriety in OUD could involve medications that are FDA-approved for this indication: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Psychosocial interventions can be used individually and in combination with pharmacotherapy. Because OUD is a chronic disorder typically characterized by intermittent relapse, patients could move back and forth between the different phases of treatment.

In this article, we highlight the medication and non-medication treatment options for the long-term management of OUD.

Defining abuseExogenous opioids are synthetic substances used for their analgesic and morphine-like properties. Opioids are indicated for the treatment of certain pain conditions and exist in varying potencies and delivery systems, which are tailored for specific types of pain.2 Opioids work through activity at opioid receptors found in the brain, spinal cord, gut, and other organs. Agonism of specific opioid receptors results in a decreased perception of pain and contributes to their abuse potential.

Because of their abuse potential, prescription of opioids is governed by the Controlled Substances Act3 of the United States. Despite these regulations, approximately 4.5% of U.S. adults from a nationally representative sample were found to be misusing prescription opioids.4 Another study used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and showed an increasing prevalence of OUD involving prescription drugs and resulting in increased mortality.5 The mortality rate from prescription opioids was found to be higher than for all other illicit drugs combined in 2013.6 Recently, Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which is intended to address the opioid crisis by expanding access to treatments for opioid overdose and addiction treatment services.7

The term “opioid use disorder” is found in DSM-58 and replaces the previous diagnoses of opioid abuse and dependence in DSM-IV-TR.9 OUD is characterized by a strong desire to continue using opioids despite problems associated with their use. Patients with OUD often experience cravings for opioids, tolerance, repeated failures at cutting down or limiting use, and decreased involvement in social activities.

Maladaptive use of opioids can result in physiologic dependence and lead to withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, drug craving, insomnia, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, diarrhea, and piloerection. However, physiologic dependence might not necessarily lead to development of OUD, which can be diagnosed when enough other diagnostic criteria present in the absence of physiologic dependence.

Misuse of prescription opioids is more prevalent among patients who meet criteria for other substance use disorders than among patients who do not.10 Misuse of prescription opioids often results in greater health care utilization, including the need for emergency services, hospitalization, and detoxification.

Assessing for OUDThe Addiction Severity Index was designed to classify and monitor misuse of opioids. The Index has poor sensitivity; it detects recent opioid use but fails to differentiate patients using prescribed opioids from those who are abusing opioids.11 By comparison, the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) was developed to monitor opioid use in chemical dependency treatment settings.12 The COMM has reliable internal consistency13 and validity and can be used to assess use of opioids outside of routine medical care. To gauge the severity of withdrawal symptoms, the Objective Opioid Withdrawal Scale or Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale14 can be used. Table 1 summarizes some standardized tools used to assess OUD.

Neurobiological considerationsOpioids work through activity at mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors. These receptors are present in both the peripheral and the central nervous system. Exogenous opioids work through activity at G protein-coupled receptors and by activating specific neurotransmitter systems. The effect of a given opioid drug is dependent on the type and location of receptors it modulates and can range from CNS depression to euphoria.

For example, mu receptor activation produces sedation, euphoria, or analgesia depending upon the location, frequency, and duration of receptor occupancy. Activation of CNS mu receptors can cause miosis and respiratory depression, whereas mu receptor activation in the peripheral nervous system can cause constipation and cough suppression. Mu receptor stimulation through various G-proteins triggers the second messenger cascade, generating enzymes such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

Clinical considerationsTreating OUD is challenging because of the ease with which patients can obtain opioids and because sometimes OUD occurs iatrogenically. Engaging patients in treatment is an important step in recovery, but it does not necessarily lead to reduction in opioid use. The engagement stage can involve outreach workers to encourage further treatment. Developing a therapeutic alliance and appropriately incentivizing patients also promotes entry into treatment. Motivational interviewing is used often in substance use treatment programs and can help engage patients in treatment and evaluate their willingness to change problematic behaviors.

Managing acute withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms usually are not life threatening, but can be in the context of other medical conditions, such as autonomic instability, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and dehydration. Withdrawal symptoms also can be life-threatening during in utero exposure to a fetus. Pharmacotherapeutic options to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms include long-acting opioids, such as methadone and buprenorphine,15 which can be administered in an ambulatory setting. The combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also can be used to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms.

The alpha-2 agonist16 clonidine, although not FDA-approved for OUD or opioid withdrawal, could be used to shorten the duration of withdrawal symptoms. Clonidine also decreases methadone withdrawal and can be combined with naloxone to target naloxone-induced opioid withdrawal symptoms.17,18 Nalbuphine and butorphanol should be avoided during opioid withdrawal because they antagonize opioid receptors and can precipitate withdrawal symptoms.19,20

Maintenance phase involves long-term stabilization and relapse prevention. Treatment options include medication and non-medication interventions.21

Non-pharmacologic treatment options,22 principally psychosocial interventions, can be used on their own or in combination with medications for maintenance treatment of OUD. Psychosocial interventions include structured, professionally administered interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), aversion therapy, and day-treatment programs. Interventions such as peer counseling and self-help groups also are considered psychosocial interventions, but do not require the same type of professional training.

Peer support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA) help members achieve and maintain sobriety and often focus on a traditional 12-step format or on the more recent Matrix Model,23,24 which is an intensive outpatient treatment program based on components of relapse prevention, motivational interviewing, CBT, and psychoeducation.

In these peer support models, group members discuss patterns of substance use and help one another recognize and overcome problematic behaviors. Groups may vary in terms of their specific approach. For example, NA encourages group members to focus on addiction itself while Methadone Anonymous prefers participants also discuss pharmacologic treatment experiences. Additional services for finding housing and assisting with job placement are also part of some relapse prevention strategies.

Although studies on the use of abstinence-based treatments are limited, abstinence-based therapy is an option for patients wishing to undergo chemical dependency treatment without taking prescription medications to address cravings or withdrawal symptoms.25 However, abstinence-based treatments have been shown to be less effective in improving outcomes than medication-assisted treatment (MAT).26 MAT combines medications and behavioral therapies for treating substance use disorders.

Pharmacologically, OUD can be treated with opioid agonist and antagonist medications. As summarized in Tables 2-4,27-31 these medications differ based on their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activity at mu opioid receptors. Opioid system agonists, such as methadone and buprenorphine, decrease cravings by mimicking the activity of exogenous opioids. The opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone reinforce abstinence by inhibiting the euphoric effects associated with opioid use. The medication of choice for a given patient depends on:

- treatment adherence

- clinical setting

- degree of withdrawal symptoms

- motivation.26

If a patient is actively seeking abstinence from opioids, either agonist or antagonist treatment can be used. In cases where a patient is not seeking abstinence, then preference should be given to opioid agonists to prevent overdose.26

Evidence suggests MAT can improve outcomes with OUD when compared with abstinence treatment alone. Several randomized, controlled, trials showed methadone and buprenorphine were more effective at treating OUD compared with treatment without medication. To date, 3 medications have been FDA-approved for treating OUD: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.26 All 3 medications differ in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activities at central mu-opioid receptor, as summarized in Tables 2-4.27-31

MethadoneMethadone reduces the euphoric effects of opioid use because it binds to and blocks opioid receptors. Methadone is an opioid replacement strategy; higher dosages are used for maintenance treatment to prevent additional dosages of opioids from causing euphoria. Methadone typically is administered once daily. However, in certain circumstances, such as rapid metabolism or pregnancy, it can be given as a twice-daily dosing regimen. Specific ABCB1 variants and DRD2 genetic polymorphisms (simultaneous occurrence of ≥2 genetically determined phenotypes) might determine the dosage requirements of methadone.32

Methadone during pregnancy. Methadone is the treatment of choice for opioid-dependent women during pregnancy33 and is listed as pregnancy category C because it can result in physiologic dependence of the newborn, although there are no documented controlled studies in humans to assess this risk. Methadone can be used while breast-feeding as long as patients are HIV-negative and not abusing other drugs.34,35 Because the methadone concentration in breast milk generally is low, the medication can be administered to nursing mothers after a careful consideration of risks and benefits.

Methadone administration. There are stringent eligibility criteria for methadone administration; not all physicians are authorized to prescribe methadone. Its use is federally regulated and only licensed treatment programs and licensed inpatient detoxification units can prescribe and dispense methadone in controlled settings and under the direct supervision of clinical personnel (Table 5).36 Patients meeting eligibility criteria can attend a specialized methadone clinic.

One of the challenges when using methadone for long-term management of OUD is tapering the dosage and attempting to discontinue the medication. Discontinuation of methadone leads to withdrawal symptoms and requires a carefully tailored tapering schedule. The literature on methadone tapering is limited. Tapering schedules could differ from practice to practice and, in many cases, are highly individualized based on the need and response of specific patients.

Dosage reduction schedules can last from 2 to 3 weeks to 6 months. Studies indicate rapid reduction worsens treatment outcomes and protracted tapering is associated with better outcomes. A suggested tapering schedule could involve decreasing the dosage by 20% to 25% until reaching a dosage of 30 mg/d, then decreasing by 5 mg/d every 3 to 5 days until reaching a dosage of 10 mg/d, before finally decreasing by 2.5 mg/d every 3 to 5 days.

Some randomized trials have shown better outcomes with long-term treatment. The goal of many programs is transitioning from maintenance treatment to abstinence. However, programs targeting maintenance rather than abstinence have been shown to be more effective.

The FDA has no defined limits for treatment duration with either methadone or buprenorphine. Therefore, the decision to taper or discontinue either medication should be made carefully case by case, using sound clinical judgment. Studies show that methadone treatment could reduce the spread of HIV,37,38 decrease criminal behaviors,39 and reduce overall mortality rates.40 A follow-up study comparing individuals randomly assigned to receive methadone or buprenorphine for OUD showed reduced risk of mortality overall40 in both groups.

Adverse events reported during treatment with methadone include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, constipation, drowsiness, QTc prolongation, and torsade de pointes.41 Therefore, the FDA recommends obtaining a detailed medical history and baseline electrocardiogram (ECG), with a repeat ECG within the first month of treatment and then annually. Informing patients about the possibility of arrhythmias is part of the informed consent process before starting methadone.

Clinicians also should be vigilant when using methadone in combination with other medications that can prolong the QTc interval (eg, some antipsychotics). Methadone has a greater risk of fatal overdose then buprenorphine. A large-scale study of >16,000 patients reported a 4-fold increase in mortality resulting from methadone overdose compared with buprenorphine.42

BuprenorphineBuprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist at the mu opioid receptor. A full opioid agonist binds and fully activates the opioid receptors; an antagonist blocks the same. An opioid receptor partial agonist partially activates the receptor. Therefore, an opioid system partial agonist is a functional antagonist and, at lower dosages, has weak agonist effects; at higher dosages, a partial agonist antagonizes other endogenous and exogenous opioids that compete for binding at the same receptor.43 Because of the partial agonist effect, buprenorphine could result in less physical dependence and less withdrawal symptoms.

Administration. In contrast to methadone, buprenorphine can be prescribed by physicians for long-term management of OUD in the United States. Buprenorphine is available in 2 formulations: a sublingual form for daily use and a long-acting form that causes less withdrawal symptoms and cravings. In May 2016 the FDA approved the first buprenorphine implant for use in opioid dependence.44,45

To prevent withdrawal symptoms, a 24-hour period of opioid abstinence is recommended before starting buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone treatment.46 Although lacking empirical evidence, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors, such as entacapone, have an anti-craving affect and are used by some clinicians to improve adherence with buprenorphine. This is because of their ability to balance dopamine, which is central to the reward pathway responsible for cravings. Although use of COMT inhibitors might make sense intuitively, such use is off-label and should be based on clinical judgment and a review of the available literature. A study showed that tapering buprenorphine for 4 weeks in combination with naltrexone improved the abstinence rate.47

Adverse effects. Some of the adverse events reported during treatment with buprenorphine include fever, back pain, nausea, cough, sedation, difficulty with urination, and constipation. Respiratory depression is a less common effect of buprenorphine, compared with full opioid agonists, because of the medication’s mechanism of action as a partial agonist.48 As a result, buprenorphine has been shown to have a lower risk of fatal overdose than methadone.49 Studies have shown buprenorphine to be more likely than methadone to reduce neonatal abstinence syndromes.50

NaltrexoneNaltrexone is an opioid antagonist and is an option to promote relapse prevention. Because of its antagonist properties, naltrexone treatment should always start after opioid detoxification because it can potentiate immediate withdrawal symptoms. Naltrexone is available in oral and long-acting formulations, the latter of which may be considered in patients who have difficulty with adherence.37

Oral naltrexone is taken as a single 50 mg-tablet once daily, whereas dosing for long-acting naltrexone in injectable and implantable formulations varies. These long-acting naltrexone formulations typically are administered monthly. Some of the adverse events reported during treatment with naltrexone are nausea, liver damage, and injection site pain.51

Buprenorphine/naloxoneBecause of buprenorphine’s agonist effects, it has a relatively high abuse potential compared with other opioids.52 Naloxone, on the other hand, is an opioid antagonist and is poorly absorbed when given orally and is associated with withdrawal symptoms if used intravenously. Therefore, naloxone is added to buprenorphine to decrease the likelihood of abuse when both are used as a combination product.53

Buprenorphine is combined with naloxone in a ratio of 4:1. Induction begins by using a 2 mg/0.5 mg tablet with dosage titration until symptoms abate. A combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also is available in film and tablet formulations. Patients must abstain from other opioids for at least 24 hours before initiating buprenorphine/naloxone treatment to prevent the precipitation of withdrawal symptoms.

1. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

2. Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1695-1700.

3. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

4. Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, et al. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1-3):38-47.

5. Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468-1478.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, 2014. Multiple cause of death data. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

7. Twachtman G. Congress sends opioid legislation to the President. Clinical Psychiatry News. http://www.clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/?id=2407&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=524025&cHash=e93d5d1f86d20e53d3e2d8b07e9562b2. Published July 15, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

10. McCabe SE, Cranford JA, West BT. Trends in prescription drug abuse and dependence, co-occurrence with other substance use disorders, and treatment utilization: results from two national surveys. Addict Behav. 2008;33(10):1297-1305.

11. Butler SF, Villapiano A, Malinow A. The effect of computer-mediated administration on self-disclosure of problems on the Addiction Severity Index. J Addict Med. 2009;3(4):194-203.

12. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152(2):397-402.

13. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(9):770-776.

14. Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253-259.

15. Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Clinical practice. Office-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):817-823.

16. Gowing LR, Farrell M, Ali RL, et al. α2‐Adrenergic agonists in opioid withdrawal. Addiction. 2002;97(1):49-58.

17. Loimer N, Hofmann P, Chaudhry H. Ultrashort noninvasive opiate detoxification. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):839.

18. Charney DS, Sternberg DE, Kleber HD, et al. The clinical use of clonidine in abrupt withdrawal from methadone. Effects on blood pressure and specific signs and symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(11):1273-1277.

19. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Antagonist effects of nalbuphine in opioid-dependent human volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248(3):929-937.

20. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Discrimination of butorphanol and nalbuphine in opioid-dependent humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;37(3):511-522.

21. Effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. National Consensus Development Panel on Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate Addiction. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1936-1943.

22. Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli, M, et al. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD004147. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub4.

23. Obert JL, McCann MJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al. The matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: history and description. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(2):157-164.

24. Mayet S, Farrell M, Ferri M, et al. Psychosocial treatment for opiate abuse and dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004330.

25. McAuliffe WE. A randomized controlled trial of recovery training and self-help for opioid addicts in New England and Hong Kong. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1990;22(2):197-209.

26. Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):63-75.

27. Gibson AE, Degenhardt LJ. Mortality related to pharmacotherapies for opioid dependence: a comparative analysis of coronial records. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:405-410.

28. Clark L, Haram E, Johnson K, et al. Getting started with medication-assisted treatment with lessons from advancing recovery. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2010.

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Vivitrol (naltrexone for extended-release injectable suspension): NDA 21-897C—Briefing document/background package. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/Psychopharmacologic DrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM225664.pdf. Published September 16, 2010. Accessed July 11, 2016.

30. Providers Clinical Support System. PCSS Guidance. Buprenorphine induction. http://pcssmat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/PCSS-MATGuidanceBuprenorphineInduction.Casadonte.pdf. Updated November 27, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2016.

31. An introduction to extended-release injectable naltrexone for the treatment of people with opioid dependence. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4682.

32. Doehring A, von Hentig N, Graff J, et al. Genetic variants altering dopamine D2 receptor expression or function modulate the risk of opiate addiction and the dosage requirements of methadone substitution. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19(6):407-414.

33. Mitchell JL. Pregnant, substance-abusing women: treatment improvement protocol (TIP) Series 2. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1993. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 95-3056.

34. McCarthy JJ, Posey BL. Methadone levels in human milk. J Hum Lact. 2000;16(2):115-120.

35. Geraghty B, Graham EA, Logan B, et al. Methadone levels in breast milk. J Hum Lact. 1997;13(3):227-230.

36. Krambeer LL, von McKnelly W Jr, Gabrielli WF Jr, et al. Methadone therapy for opioid dependence. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(12):2404-2410.

37. Novick DM, Joseph H, Croxson TS, et al. Absence of antibody to human immunodeficiency virus in long-term, socially rehabilitated methadone maintenance patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(1):97-99.

38. Gowing LR, Farrell M, Bornemann R, et al. Brief report: methadone treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):193-195.

39. Nurco DN, Ball JC, Shaffer JW, et al. The criminality of narcotic addicts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(2):94-102.

40. Gibson A, Degenhardt L, Mattick RP, et al. Exposure to opioid maintenance treatment reduces long-term mortality. Addiction. 2008;103(3):462-468.

41. Pearson EC, Woosley RL. QT prolongation and torsades de pointes among methadone users: reports to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(11):747-753.

42. Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, et al. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1-2):73-77.

43. Bickel WK, Amass L. Buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: a review. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;3(4):477-489.

44. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first buprenorphine implant for treatment of opioid dependence. http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm503719.htm. Published May 26, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

45. The National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment. https://www.naabt.org/index.cfm. Accessed July 18, 2016.

46. Buprenorphine: an alternative to methadone. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2003;45(1150):13-15.

47. Sigmon SC, Dunn KE, Saulsgiver K, et al. A randomized, double-blind evaluation of buprenorphine taper duration in primary prescription opioid abusers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1347-1354.

48. Dahan A, Yassen A, Bijl H, et al. Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(6):825-834.

49. Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, et al. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1-2):73-77.

50. Kakko J, Heilig M, Sarman I. Buprenorphine and methadone treatment of opiate dependence during pregnancy: comparison of fetal growth and neonatal outcomes in two consecutive case series. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(1-2):69-78.

51. Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, Kosten TR. Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(11):1727-1740.

52. Robinson GM, Dukes PD, Robinson BJ, et al. The misuse of buprenorphine and a buprenorphine-naloxone combination in Wellington, New Zealand. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33(1):81-86.

53. Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al; Buprenorphine/Naloxone Collaborative Study Group. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):949-958.

1. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

2. Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1695-1700.

3. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

4. Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, et al. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1-3):38-47.

5. Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468-1478.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, 2014. Multiple cause of death data. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

7. Twachtman G. Congress sends opioid legislation to the President. Clinical Psychiatry News. http://www.clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/?id=2407&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=524025&cHash=e93d5d1f86d20e53d3e2d8b07e9562b2. Published July 15, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

10. McCabe SE, Cranford JA, West BT. Trends in prescription drug abuse and dependence, co-occurrence with other substance use disorders, and treatment utilization: results from two national surveys. Addict Behav. 2008;33(10):1297-1305.

11. Butler SF, Villapiano A, Malinow A. The effect of computer-mediated administration on self-disclosure of problems on the Addiction Severity Index. J Addict Med. 2009;3(4):194-203.

12. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152(2):397-402.

13. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(9):770-776.

14. Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253-259.

15. Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Clinical practice. Office-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):817-823.

16. Gowing LR, Farrell M, Ali RL, et al. α2‐Adrenergic agonists in opioid withdrawal. Addiction. 2002;97(1):49-58.

17. Loimer N, Hofmann P, Chaudhry H. Ultrashort noninvasive opiate detoxification. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):839.

18. Charney DS, Sternberg DE, Kleber HD, et al. The clinical use of clonidine in abrupt withdrawal from methadone. Effects on blood pressure and specific signs and symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(11):1273-1277.

19. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Antagonist effects of nalbuphine in opioid-dependent human volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248(3):929-937.

20. Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Discrimination of butorphanol and nalbuphine in opioid-dependent humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;37(3):511-522.

21. Effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. National Consensus Development Panel on Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate Addiction. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1936-1943.

22. Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli, M, et al. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD004147. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub4.

23. Obert JL, McCann MJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al. The matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: history and description. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(2):157-164.