User login

I’ve seen my share of missed diagnoses over the years while caring for patients who, through physician- or self-referral, have made their way to our multi-specialty group practice where I focus solely on skin.

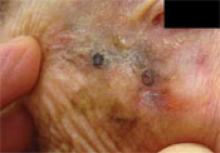

There was the 93-year-old patient whose “sun spot” had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists in the past and turned out to be a lentigo maligna melanoma (FIGURE 1).

There was the patient who had a lesion on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years” that neither caught the attention of her physician, nor her dentist (FIGURE 2). Histology showed she had an infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

And then there was the wife of a healthcare professional who decided she wanted a “second opinion” for the asymptomatic lesion on her leg that her husband assured her was benign. Her diagnosis was not so simple: She had a MELanocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP) that required careful follow-up (FIGURE 3).

Early detection, as we all know, is the name of the game when it comes to skin malignancies. Yet every day, opportunities to catch small, early lesions are missed.

During the past couple of years, I’ve had thousands of patient visits for skin problems and diagnosed more than 1000 skin malignancies. The majority of patients have had some treatment for their presenting dermatosis prior to arrival. Based on my experiences with these patients, I’ve developed a list of common dermatology “mistakes.” Here they are, with some tips for avoiding them.

FIGURE 1

Melanoma missed by 2 dermatologists

This “sun spot” was of no concern to the 93-year-old patient because she had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists. The darkest areas are dermoscopically-directed pen markings for incisional biopsy. (The size of the lesion and proximity to the eye precluded primary excisional biopsy.) This “sun spot” turned out to be lentigo maligna melanoma.

FIGURE 2

Lesion on lip for “10—maybe 20—years”

This patient had a lesion that had been on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years.” The patient said it had never bled or crusted. Telangiectasia, pearliness, and some infiltration were present. Histologic diagnosis: infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3

A case of MELTUMP

Two dermatopathologists read the biopsy as Spitzoid malignant melanoma, Clark Level III, and Breslow thickness 0.9 mm. Two independent dermatopathologists read the same original slides in consultation as atypical Spitz nevus. The 4 could not reach agreement. Final clinical diagnosis: MEL anocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP).

Mistake #1: Not looking (and not biopsying)

I had a woman come into the office to have a lesion assessed. She had seen a dermatologist a couple of weeks earlier and even had a number of lesions removed during that visit. The patient told me that she’d repeatedly tried to show the dermatologist one specific lesion—the one of greatest concern to her—just below her underpants line, but the physician was in and out so fast each time, she never had the chance to point out this one melanocytic, changing lesion.

The lesion turned out to be a dysplastic nevus with severe architectural and cytologic atypia. This type of lesion requires histology to differentiate it from melanoma, and could just as easily have been a melanoma.

Almost daily I treat patients who are being seen by their primary care physicians regularly, and have obvious basal cell carcinomas (BCC) or squamous cell carcinomas. I have even found skin malignancies on physicians, their spouses, and their family members.1 These lesions can be easily missed—if you don’t look carefully.

Consider, the following:

- FIGURE 4 illustrates a superficial BCC on the forearm of a physician who was totally unaware of it. (It was detected on “routine” skin examination.)

- FIGURE 5 illustrates a BCC on a patient’s central forehead that, by her history, had been there for many years, and was not of any concern to her. The patient was referred to our office for evaluation of itchy skin on her legs.

- FIGURE 2 illustrates a lesion that, according to the patient, had been on her lip for at least 10—and perhaps even 20—years and was of no concern to her. (It was not the reason for the visit.) Over the years, this patient certainly had numerous primary care and dental visits, but no one “saw” the lesion. Histology confirmed the clinical impression of BCC.

FIGURE 4

Superficial BCC on physician’s forearm

A physician asked for a skin examination, but was totally unaware of this asymptomatic lesion on his dorsal forearm. Once it was identified, he could provide no history about its duration. The lesion had never bled or crusted. Pathology confirmed that it was a superficial basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 5

“Mole” on forehead for many years

This patient was referred for itchy legs. She was unconcerned about a prominent “mole” noted on examination of her forehead, one that she said had been there, unchanged, for many years. Histology confirmed nodular basal cell carcinoma.

- Look, look, and look again, especially at sun-exposed areas (faces, ears, scalps [as hair thins], and dorsal forearms).

- Make sure patients are appropriately gowned no matter what the reason for their visit. Listening to heart and lung sounds and palpating abdomens through overcoats may work for some physicians, but not those interested in finding asymptomatic basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. Melanoma in men is most common on the back; in women, it’s most common on the legs. Seeing these areas requires that they be accessible.

- Biopsy when you’re in doubt. If you see a lesion and it is not recognizable as benign (eg, cherry angioma, seborrheic keratosis, nevus), biopsy it. Let the pathologist determine if it’s benign or malignant. If the lesion is questionable and is in an area that you are uncomfortable biopsying, refer the patient for evaluation and potential biopsy.

Mistake #2: Using insufficient light

As a former family practice academic, I used to preach to residents that they needed to use “light, light, and more light” for evaluation of skin lesions. Despite this, I was often asked to evaluate a patient with a resident who hadn’t even bothered to turn on a goose-neck lamp for illumination.

Even with my current “double bank” daylight fluorescent examination room lighting, it often takes additional (surgical-type) lighting to see the diagnostic features of skin lesions. Without such intense light, it is often impossible to see whether there is pearliness, rolled edges, or fine telangiectasia.

- Use whatever intense source of light you have, whether it’s a goose-neck lamp, a halogen, or a surgical light. If you don’t have at least a portable source of bright light, you are under-equipped for a good skin exam.

Mistake #3: Using insufficient (or no) magnification

I was once examining a patient in a hospital room that had inadequate light, despite my best efforts. So I took out my digital camera with flash and autofocus feature and photographed the lesion. I then looked at the lesion on the camera’s LCD monitor and determined that it was a BCC.

The benefit of the camera was 2-fold: Not only did the flash serve as an instant source of light, but the macro feature also provided magnification. Viewing a magnified digital image on a computer screen also allows unhurried, self “second opinions,” where details can often be ascertained that were not immediately apparent in “real time,” such as rolled edges, telangiectasia, dots, streaks, and subtleties of color.

- Use a hand-held magnifying lens (5X to 10X) routinely during skin exams. They’re not expensive and should be part of every primary care physician’s armamentarium—just like stethoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and reflex hammers.

- Use a digital camera to provide the magnification needed to see details that can be missed clinically. I’m convinced that using a digital camera has made me a better observer—and clinician. Additionally, digital photographs can be stored and compared with histologic results as “self-education.” When purchasing a camera for this purpose, make sure it has a good close-up (macro) feature.

Mistake #4: Assuming that pathology is a perfect science

Most physicians assume that dermatopathologists have a high rate of interrater concordance with diagnoses such as melanoma. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Consider the following:

- As part of a National Institutes of Health consensus conference on melanoma, 8 dermatopathologists considered experts in melanoma were asked to provide 5 slides each. The slides were relabeled and sent to the same 8 dermatopathologists. (Three slides were eliminated.) Their findings: At the extremes, 1 pathologist called 21 cases melanoma and 16 benign, whereas another called 10 melanoma, 26 benign, and one indeterminate.2 (Remember: These were all experts in melanoma.)

- In a study of 30 melanocytic lesion specimens (including Spitzoid lesions), 10 Harvard dermatopathologists evaluated each sample independently of each other. Given 5 diagnostic categories to choose from, in only one case did as many as 6 of the 10 agree on a diagnosis. In all of these cases, there was long-term clinical follow-up, so the biologic behavior of these lesions was known. Some lesions that proved fatal were categorized by most observers as benign (eg, Spitz nevi or atypical Spitz tumors). The converse, reporting benign lesions as melanoma, also occurred.3

So consider this: If this degree of discordance occurs among dermatopathologists, what results could we expect from non-dermatopathologists?

I have personally seen instances where reports of melanoma from non-dermatopathologists did not even report Clark and Breslow staging information (although one could determine Clark staging from reading the body of the report), and reports of dysplastic nevi that were accompanied by recommendations for re-excision with 1 cm margins.

When I have a report from a general pathologist suggesting a potentially worrisome lesion (melanoma, severely dysplastic nevus, [atypical] Spitz nevus), I always suggest to my patients that we get a dermatopathologic second opinion. (I send all my dermatopathology specimens to dermatopathologists, so this applies to patients referred in with prior pathology in hand.)

Sometimes, even the dermatopathologists do not agree on the nature of the lesion. In such cases, I have my “MELTUMP discussion” with patients. That is, I tell patients that we don’t know for sure what it is, and that ultimately only the final lab test—time—will tell us the true nature of the lesion (FIGURE 3).4

- Send all “skin” to a dermatopathologist. You owe it to your patients.

- Send pictures (electronic or hard copy) to the dermatopathologist when the pathology report and clinical picture do not appear to match. While pictures of skin lesions and dermoscopic photographs would most likely be meaningless to general pathologists, they are useful to dermatopathologists. Research has shown that pathologists in various areas of medicine may alter their diagnosis or differential diagnosis when presented with additional clinical information.5

Mistake #5: Freezing neoplasms without a definitive Dx

“We’ll freeze it and if it doesn’t go away, then…”

This approach poses a significant risk to you (medicolegally) and your patient.

While most of the time what I see has been inappropriately frozen first by first-line providers, that is not always the case. Dermatologists also fall into this trap. FIGURE 6 shows a lesion just behind the hairline on the frontoparietal scalp that was frozen by a very good, and reputable, dermatologist. The patient came to me for a second opinion with an “obvious” BCC.

Some clinicians are “thrown off” when a lesion (like the one on this patient) has hair. Some sources6 indicate that BCCs never have hair, but this is patently untrue.

FIGURE 6

This shouldn’t have been frozen

A dermatologist froze this lesion on a patient’s scalp, believing that it was seborrheic keratosis, based on the patient’s history. The patient sought a second opinion, and the lesion (which had hair) was histologically identified as basal cell carcinoma.

- Don’t freeze a lesion when you are unsure; biopsy it. This is especially critical when you consider that cryotherapy is not considered a first-line treatment for BCC, the most common human malignancy. It is better to biopsy, assure the diagnosis, and then provide the appropriate therapy.

Mistake #6: Treating psoriasis with systemic corticosteroids

Plaque psoriasis can, albeit uncommonly, be transformed to pustular psoriasis after the administration of oral or injectable systemic corticosteroids.7 Although this rarely occurs, most experts consider this poor practice and not worth the risk. In addition, some experts note that systemic glucocorticoids are a drug trigger for inducing or exacerbating psoriasis.8

- Avoid systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis, since psoriasis is generally a long-term disease and systemic corticosteroids are a short-term fix. if there is widespread psoriasis and you are not familiar with systemic treatments, refer the patient. If there is localized disease, consider topical treatment options—such as various strengths of corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tazarotene (individually or in combination)—depending on location and plaque thickness.

Mistake #7: Doing shave biopsies on melanocytic lesions

For a melanoma, not only can shaving part way through the vertical dimension of the lesion interfere with staging, it can also hinder the pathologist’s ability to arrive at the correct diagnosis.9

- Do a full-thickness, narrow-margin, fully excisional biopsy when you suspect melanoma. Certainly, there are individuals who are expert at saucerization (deep shave biopsies, often with scalloped, sloping edges that go to the deep reticular dermis) and who can perform biopsies of melanocytic lesions while still obtaining reasonable pathologic staging information.

Mistake #8: Using corticosteroid/antifungal combination products

Corticosteroid/antifungal combination products are generally shunned by dermatologists, although they are used extensively by nondermatologists.9 The difficulty with a preparation like Lotrisone, which contains a class III corticosteroid (betamethasone dipropionate [Diprosone]) and the antifungal clotrimazole, is that it is often used long-term for presumed fungal infection on thin-skinned areas. Unfortunately, though, chronic use in these areas can lead to atrophy and striae (FIGURE 7).

Additionally, corticosteroid is essentially “fungus food.” Majocchi’s granulomas can form because the corticosteroid interferes with clotrimazole’s antifungal effect. Note also that these combination products can suppress fungus sufficiently to render cultures and KOH preparations falsely negative and alter the clinical appearance of psoriasiform dermatitis, interfering with subsequent, accurate diagnosis.

FIGURE 7

Striae after corticosteroid combination therapy

This patient developed striae and atrophy after using a combination high-potency topical corticosteroid/antifungal preparation in a thin-skinned area (proximal medial thigh). It was unclear what the prescriber was treating.

- Consider compounding with miconazole powder and hydrocortisone powder, if a corticosteroid/antifungal combination is necessary (which it rarely is). For example, hydrocortisone 1% or 0.5% ointment can be compounded with miconazole powder for short-term, careful external application, in cases of angular cheilitis.

- Limit your use of a topical corticosteroid for a fungal eruption (if one must be used) to the first few days of treatment. The corticosteroid class should be appropriate to the site of application.9

- Counsel your patients about the risks of using topical corticosteroids on thinskinned areas for more than a few days (few weeks, maximum). On the face, corticosteroids can cause rosacea and perioral dermatitis, as well as “rebound” vasodilation. Thus, topical corticosteroids should be used with great caution—and generally as a last resort—for chronic facial dermatoses.

Mistake #9: Corticosteroid underdosing and undercounseling

It’s not uncommon during the warm weather months for me to see patients who are near finishing a Medrol Dosepak that was prescribed by their primary care physicians for a case of contact dermatitis (eg, poison ivy). They come to me because the eruption has returned and it is “as bad as ever.”

Underdosing. Medrol Dosepaks are generally underpowered (too low a dosage) and too short a course.7,10,11

Undercounseling. Patients don’t always realize that contact dermatitis may actually last for 3 weeks or longer. They may also mistakenly believe that systemic treatment will get them through the whole episode (rather than the worst part).

- Design your own prednisone taper for when such tapers are needed. You might even have the prescription, with taper, prefilled on paper for signature. for significant allergic contact dermatitis, the taper may last 2 weeks.

- Dispel myths. Assure patients that by taking a thorough soap shower (and laundering the clothing they were wearing), they will remove all of the oil responsible for the disease.

- Limit your use of injectable corticosteroids. There is little need for injectable corticosteroids in cases of contact dermatitis. Oral corticosteroids work just as well, can be more easily titered based on response, and pose no injection risk of tissue atrophy or abscess formation.9

Mistake #10: Requiring red flags in both history and exam

Skin diagnosis is an “or” game—not an “and” game. By that I mean: If either the history (eg, rapid change, bleeding, crusting, nonhealing ulcer) or the examination is worrisome, biopsy. Even dermoscopy can be completely reassuring with biopsy yielding a melanoma.12 Note, too, our earlier examples of patients with suspect examinations who gave reassuring histories of lesions that had been present for many years. Either a worrisome history or a suspect examination is sufficient for concern. Remember, in general, the worst-case scenario from a biopsy is a scar; from a missed melanoma, an autopsy report.

- Get back to basics. Look carefully at your patient’s skin—even if it’s not the reason for the visit. Take a moment to ask your patient: Do you have any changing lesions or is there anything on your skin that is scaly, bleeding, or crusting? Doing so will cut down on the number of patients who ultimately learn that the lesion that’s “always been there,” and that “didn’t worry the other doctors” is actually a skin cancer.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, 1400 E 2nd St, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Fox GN, Mehregan DR. A new papule and “age spots.” J Fam Pract 2007;56:278-282.

2. Farmer ER, Gonin R, Hanna MP. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma and melanocytic nevi between expert pathologists. Hum Pathol 1996;27:528-531.

3. Barnhill RL, Argenyi ZB, From L, et al. Atypical Spitz nevi/tumors: lack of consensus for diagnosis, discrimination from melanoma, and prediction of outcome. Hum Pathol 1999;30:513-520.

4. Elder DE, Xu X. The approach to the patient with a difficult melanocytic lesion. Pathology 2004;36:428-434.

5. McBroom HM, Ramsay AD. The clinicopathological meeting. A means of auditing diagnostic performance. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:75-80.

6. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004.

7. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004.

8. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

9. Edwards L. Dermatology in Emergency Care. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

10. Brodell RT, Williams L. Taking the itch out of poison ivy. Postgrad Med 1999;106:69-70.

11. Hall JC. Dermatologic allergy. In: Hall JC, ed. Sauer’s Manual of Skin Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:82.

12. Braun RP, Gaide O, Skaria AM, Kopf AW, Saurat JH, Marghoob AA. Exclusively benign dermoscopic pattern in a patient with acral melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:1213-1215.

I’ve seen my share of missed diagnoses over the years while caring for patients who, through physician- or self-referral, have made their way to our multi-specialty group practice where I focus solely on skin.

There was the 93-year-old patient whose “sun spot” had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists in the past and turned out to be a lentigo maligna melanoma (FIGURE 1).

There was the patient who had a lesion on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years” that neither caught the attention of her physician, nor her dentist (FIGURE 2). Histology showed she had an infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

And then there was the wife of a healthcare professional who decided she wanted a “second opinion” for the asymptomatic lesion on her leg that her husband assured her was benign. Her diagnosis was not so simple: She had a MELanocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP) that required careful follow-up (FIGURE 3).

Early detection, as we all know, is the name of the game when it comes to skin malignancies. Yet every day, opportunities to catch small, early lesions are missed.

During the past couple of years, I’ve had thousands of patient visits for skin problems and diagnosed more than 1000 skin malignancies. The majority of patients have had some treatment for their presenting dermatosis prior to arrival. Based on my experiences with these patients, I’ve developed a list of common dermatology “mistakes.” Here they are, with some tips for avoiding them.

FIGURE 1

Melanoma missed by 2 dermatologists

This “sun spot” was of no concern to the 93-year-old patient because she had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists. The darkest areas are dermoscopically-directed pen markings for incisional biopsy. (The size of the lesion and proximity to the eye precluded primary excisional biopsy.) This “sun spot” turned out to be lentigo maligna melanoma.

FIGURE 2

Lesion on lip for “10—maybe 20—years”

This patient had a lesion that had been on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years.” The patient said it had never bled or crusted. Telangiectasia, pearliness, and some infiltration were present. Histologic diagnosis: infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3

A case of MELTUMP

Two dermatopathologists read the biopsy as Spitzoid malignant melanoma, Clark Level III, and Breslow thickness 0.9 mm. Two independent dermatopathologists read the same original slides in consultation as atypical Spitz nevus. The 4 could not reach agreement. Final clinical diagnosis: MEL anocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP).

Mistake #1: Not looking (and not biopsying)

I had a woman come into the office to have a lesion assessed. She had seen a dermatologist a couple of weeks earlier and even had a number of lesions removed during that visit. The patient told me that she’d repeatedly tried to show the dermatologist one specific lesion—the one of greatest concern to her—just below her underpants line, but the physician was in and out so fast each time, she never had the chance to point out this one melanocytic, changing lesion.

The lesion turned out to be a dysplastic nevus with severe architectural and cytologic atypia. This type of lesion requires histology to differentiate it from melanoma, and could just as easily have been a melanoma.

Almost daily I treat patients who are being seen by their primary care physicians regularly, and have obvious basal cell carcinomas (BCC) or squamous cell carcinomas. I have even found skin malignancies on physicians, their spouses, and their family members.1 These lesions can be easily missed—if you don’t look carefully.

Consider, the following:

- FIGURE 4 illustrates a superficial BCC on the forearm of a physician who was totally unaware of it. (It was detected on “routine” skin examination.)

- FIGURE 5 illustrates a BCC on a patient’s central forehead that, by her history, had been there for many years, and was not of any concern to her. The patient was referred to our office for evaluation of itchy skin on her legs.

- FIGURE 2 illustrates a lesion that, according to the patient, had been on her lip for at least 10—and perhaps even 20—years and was of no concern to her. (It was not the reason for the visit.) Over the years, this patient certainly had numerous primary care and dental visits, but no one “saw” the lesion. Histology confirmed the clinical impression of BCC.

FIGURE 4

Superficial BCC on physician’s forearm

A physician asked for a skin examination, but was totally unaware of this asymptomatic lesion on his dorsal forearm. Once it was identified, he could provide no history about its duration. The lesion had never bled or crusted. Pathology confirmed that it was a superficial basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 5

“Mole” on forehead for many years

This patient was referred for itchy legs. She was unconcerned about a prominent “mole” noted on examination of her forehead, one that she said had been there, unchanged, for many years. Histology confirmed nodular basal cell carcinoma.

- Look, look, and look again, especially at sun-exposed areas (faces, ears, scalps [as hair thins], and dorsal forearms).

- Make sure patients are appropriately gowned no matter what the reason for their visit. Listening to heart and lung sounds and palpating abdomens through overcoats may work for some physicians, but not those interested in finding asymptomatic basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. Melanoma in men is most common on the back; in women, it’s most common on the legs. Seeing these areas requires that they be accessible.

- Biopsy when you’re in doubt. If you see a lesion and it is not recognizable as benign (eg, cherry angioma, seborrheic keratosis, nevus), biopsy it. Let the pathologist determine if it’s benign or malignant. If the lesion is questionable and is in an area that you are uncomfortable biopsying, refer the patient for evaluation and potential biopsy.

Mistake #2: Using insufficient light

As a former family practice academic, I used to preach to residents that they needed to use “light, light, and more light” for evaluation of skin lesions. Despite this, I was often asked to evaluate a patient with a resident who hadn’t even bothered to turn on a goose-neck lamp for illumination.

Even with my current “double bank” daylight fluorescent examination room lighting, it often takes additional (surgical-type) lighting to see the diagnostic features of skin lesions. Without such intense light, it is often impossible to see whether there is pearliness, rolled edges, or fine telangiectasia.

- Use whatever intense source of light you have, whether it’s a goose-neck lamp, a halogen, or a surgical light. If you don’t have at least a portable source of bright light, you are under-equipped for a good skin exam.

Mistake #3: Using insufficient (or no) magnification

I was once examining a patient in a hospital room that had inadequate light, despite my best efforts. So I took out my digital camera with flash and autofocus feature and photographed the lesion. I then looked at the lesion on the camera’s LCD monitor and determined that it was a BCC.

The benefit of the camera was 2-fold: Not only did the flash serve as an instant source of light, but the macro feature also provided magnification. Viewing a magnified digital image on a computer screen also allows unhurried, self “second opinions,” where details can often be ascertained that were not immediately apparent in “real time,” such as rolled edges, telangiectasia, dots, streaks, and subtleties of color.

- Use a hand-held magnifying lens (5X to 10X) routinely during skin exams. They’re not expensive and should be part of every primary care physician’s armamentarium—just like stethoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and reflex hammers.

- Use a digital camera to provide the magnification needed to see details that can be missed clinically. I’m convinced that using a digital camera has made me a better observer—and clinician. Additionally, digital photographs can be stored and compared with histologic results as “self-education.” When purchasing a camera for this purpose, make sure it has a good close-up (macro) feature.

Mistake #4: Assuming that pathology is a perfect science

Most physicians assume that dermatopathologists have a high rate of interrater concordance with diagnoses such as melanoma. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Consider the following:

- As part of a National Institutes of Health consensus conference on melanoma, 8 dermatopathologists considered experts in melanoma were asked to provide 5 slides each. The slides were relabeled and sent to the same 8 dermatopathologists. (Three slides were eliminated.) Their findings: At the extremes, 1 pathologist called 21 cases melanoma and 16 benign, whereas another called 10 melanoma, 26 benign, and one indeterminate.2 (Remember: These were all experts in melanoma.)

- In a study of 30 melanocytic lesion specimens (including Spitzoid lesions), 10 Harvard dermatopathologists evaluated each sample independently of each other. Given 5 diagnostic categories to choose from, in only one case did as many as 6 of the 10 agree on a diagnosis. In all of these cases, there was long-term clinical follow-up, so the biologic behavior of these lesions was known. Some lesions that proved fatal were categorized by most observers as benign (eg, Spitz nevi or atypical Spitz tumors). The converse, reporting benign lesions as melanoma, also occurred.3

So consider this: If this degree of discordance occurs among dermatopathologists, what results could we expect from non-dermatopathologists?

I have personally seen instances where reports of melanoma from non-dermatopathologists did not even report Clark and Breslow staging information (although one could determine Clark staging from reading the body of the report), and reports of dysplastic nevi that were accompanied by recommendations for re-excision with 1 cm margins.

When I have a report from a general pathologist suggesting a potentially worrisome lesion (melanoma, severely dysplastic nevus, [atypical] Spitz nevus), I always suggest to my patients that we get a dermatopathologic second opinion. (I send all my dermatopathology specimens to dermatopathologists, so this applies to patients referred in with prior pathology in hand.)

Sometimes, even the dermatopathologists do not agree on the nature of the lesion. In such cases, I have my “MELTUMP discussion” with patients. That is, I tell patients that we don’t know for sure what it is, and that ultimately only the final lab test—time—will tell us the true nature of the lesion (FIGURE 3).4

- Send all “skin” to a dermatopathologist. You owe it to your patients.

- Send pictures (electronic or hard copy) to the dermatopathologist when the pathology report and clinical picture do not appear to match. While pictures of skin lesions and dermoscopic photographs would most likely be meaningless to general pathologists, they are useful to dermatopathologists. Research has shown that pathologists in various areas of medicine may alter their diagnosis or differential diagnosis when presented with additional clinical information.5

Mistake #5: Freezing neoplasms without a definitive Dx

“We’ll freeze it and if it doesn’t go away, then…”

This approach poses a significant risk to you (medicolegally) and your patient.

While most of the time what I see has been inappropriately frozen first by first-line providers, that is not always the case. Dermatologists also fall into this trap. FIGURE 6 shows a lesion just behind the hairline on the frontoparietal scalp that was frozen by a very good, and reputable, dermatologist. The patient came to me for a second opinion with an “obvious” BCC.

Some clinicians are “thrown off” when a lesion (like the one on this patient) has hair. Some sources6 indicate that BCCs never have hair, but this is patently untrue.

FIGURE 6

This shouldn’t have been frozen

A dermatologist froze this lesion on a patient’s scalp, believing that it was seborrheic keratosis, based on the patient’s history. The patient sought a second opinion, and the lesion (which had hair) was histologically identified as basal cell carcinoma.

- Don’t freeze a lesion when you are unsure; biopsy it. This is especially critical when you consider that cryotherapy is not considered a first-line treatment for BCC, the most common human malignancy. It is better to biopsy, assure the diagnosis, and then provide the appropriate therapy.

Mistake #6: Treating psoriasis with systemic corticosteroids

Plaque psoriasis can, albeit uncommonly, be transformed to pustular psoriasis after the administration of oral or injectable systemic corticosteroids.7 Although this rarely occurs, most experts consider this poor practice and not worth the risk. In addition, some experts note that systemic glucocorticoids are a drug trigger for inducing or exacerbating psoriasis.8

- Avoid systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis, since psoriasis is generally a long-term disease and systemic corticosteroids are a short-term fix. if there is widespread psoriasis and you are not familiar with systemic treatments, refer the patient. If there is localized disease, consider topical treatment options—such as various strengths of corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tazarotene (individually or in combination)—depending on location and plaque thickness.

Mistake #7: Doing shave biopsies on melanocytic lesions

For a melanoma, not only can shaving part way through the vertical dimension of the lesion interfere with staging, it can also hinder the pathologist’s ability to arrive at the correct diagnosis.9

- Do a full-thickness, narrow-margin, fully excisional biopsy when you suspect melanoma. Certainly, there are individuals who are expert at saucerization (deep shave biopsies, often with scalloped, sloping edges that go to the deep reticular dermis) and who can perform biopsies of melanocytic lesions while still obtaining reasonable pathologic staging information.

Mistake #8: Using corticosteroid/antifungal combination products

Corticosteroid/antifungal combination products are generally shunned by dermatologists, although they are used extensively by nondermatologists.9 The difficulty with a preparation like Lotrisone, which contains a class III corticosteroid (betamethasone dipropionate [Diprosone]) and the antifungal clotrimazole, is that it is often used long-term for presumed fungal infection on thin-skinned areas. Unfortunately, though, chronic use in these areas can lead to atrophy and striae (FIGURE 7).

Additionally, corticosteroid is essentially “fungus food.” Majocchi’s granulomas can form because the corticosteroid interferes with clotrimazole’s antifungal effect. Note also that these combination products can suppress fungus sufficiently to render cultures and KOH preparations falsely negative and alter the clinical appearance of psoriasiform dermatitis, interfering with subsequent, accurate diagnosis.

FIGURE 7

Striae after corticosteroid combination therapy

This patient developed striae and atrophy after using a combination high-potency topical corticosteroid/antifungal preparation in a thin-skinned area (proximal medial thigh). It was unclear what the prescriber was treating.

- Consider compounding with miconazole powder and hydrocortisone powder, if a corticosteroid/antifungal combination is necessary (which it rarely is). For example, hydrocortisone 1% or 0.5% ointment can be compounded with miconazole powder for short-term, careful external application, in cases of angular cheilitis.

- Limit your use of a topical corticosteroid for a fungal eruption (if one must be used) to the first few days of treatment. The corticosteroid class should be appropriate to the site of application.9

- Counsel your patients about the risks of using topical corticosteroids on thinskinned areas for more than a few days (few weeks, maximum). On the face, corticosteroids can cause rosacea and perioral dermatitis, as well as “rebound” vasodilation. Thus, topical corticosteroids should be used with great caution—and generally as a last resort—for chronic facial dermatoses.

Mistake #9: Corticosteroid underdosing and undercounseling

It’s not uncommon during the warm weather months for me to see patients who are near finishing a Medrol Dosepak that was prescribed by their primary care physicians for a case of contact dermatitis (eg, poison ivy). They come to me because the eruption has returned and it is “as bad as ever.”

Underdosing. Medrol Dosepaks are generally underpowered (too low a dosage) and too short a course.7,10,11

Undercounseling. Patients don’t always realize that contact dermatitis may actually last for 3 weeks or longer. They may also mistakenly believe that systemic treatment will get them through the whole episode (rather than the worst part).

- Design your own prednisone taper for when such tapers are needed. You might even have the prescription, with taper, prefilled on paper for signature. for significant allergic contact dermatitis, the taper may last 2 weeks.

- Dispel myths. Assure patients that by taking a thorough soap shower (and laundering the clothing they were wearing), they will remove all of the oil responsible for the disease.

- Limit your use of injectable corticosteroids. There is little need for injectable corticosteroids in cases of contact dermatitis. Oral corticosteroids work just as well, can be more easily titered based on response, and pose no injection risk of tissue atrophy or abscess formation.9

Mistake #10: Requiring red flags in both history and exam

Skin diagnosis is an “or” game—not an “and” game. By that I mean: If either the history (eg, rapid change, bleeding, crusting, nonhealing ulcer) or the examination is worrisome, biopsy. Even dermoscopy can be completely reassuring with biopsy yielding a melanoma.12 Note, too, our earlier examples of patients with suspect examinations who gave reassuring histories of lesions that had been present for many years. Either a worrisome history or a suspect examination is sufficient for concern. Remember, in general, the worst-case scenario from a biopsy is a scar; from a missed melanoma, an autopsy report.

- Get back to basics. Look carefully at your patient’s skin—even if it’s not the reason for the visit. Take a moment to ask your patient: Do you have any changing lesions or is there anything on your skin that is scaly, bleeding, or crusting? Doing so will cut down on the number of patients who ultimately learn that the lesion that’s “always been there,” and that “didn’t worry the other doctors” is actually a skin cancer.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, 1400 E 2nd St, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

I’ve seen my share of missed diagnoses over the years while caring for patients who, through physician- or self-referral, have made their way to our multi-specialty group practice where I focus solely on skin.

There was the 93-year-old patient whose “sun spot” had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists in the past and turned out to be a lentigo maligna melanoma (FIGURE 1).

There was the patient who had a lesion on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years” that neither caught the attention of her physician, nor her dentist (FIGURE 2). Histology showed she had an infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

And then there was the wife of a healthcare professional who decided she wanted a “second opinion” for the asymptomatic lesion on her leg that her husband assured her was benign. Her diagnosis was not so simple: She had a MELanocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP) that required careful follow-up (FIGURE 3).

Early detection, as we all know, is the name of the game when it comes to skin malignancies. Yet every day, opportunities to catch small, early lesions are missed.

During the past couple of years, I’ve had thousands of patient visits for skin problems and diagnosed more than 1000 skin malignancies. The majority of patients have had some treatment for their presenting dermatosis prior to arrival. Based on my experiences with these patients, I’ve developed a list of common dermatology “mistakes.” Here they are, with some tips for avoiding them.

FIGURE 1

Melanoma missed by 2 dermatologists

This “sun spot” was of no concern to the 93-year-old patient because she had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists. The darkest areas are dermoscopically-directed pen markings for incisional biopsy. (The size of the lesion and proximity to the eye precluded primary excisional biopsy.) This “sun spot” turned out to be lentigo maligna melanoma.

FIGURE 2

Lesion on lip for “10—maybe 20—years”

This patient had a lesion that had been on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years.” The patient said it had never bled or crusted. Telangiectasia, pearliness, and some infiltration were present. Histologic diagnosis: infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3

A case of MELTUMP

Two dermatopathologists read the biopsy as Spitzoid malignant melanoma, Clark Level III, and Breslow thickness 0.9 mm. Two independent dermatopathologists read the same original slides in consultation as atypical Spitz nevus. The 4 could not reach agreement. Final clinical diagnosis: MEL anocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP).

Mistake #1: Not looking (and not biopsying)

I had a woman come into the office to have a lesion assessed. She had seen a dermatologist a couple of weeks earlier and even had a number of lesions removed during that visit. The patient told me that she’d repeatedly tried to show the dermatologist one specific lesion—the one of greatest concern to her—just below her underpants line, but the physician was in and out so fast each time, she never had the chance to point out this one melanocytic, changing lesion.

The lesion turned out to be a dysplastic nevus with severe architectural and cytologic atypia. This type of lesion requires histology to differentiate it from melanoma, and could just as easily have been a melanoma.

Almost daily I treat patients who are being seen by their primary care physicians regularly, and have obvious basal cell carcinomas (BCC) or squamous cell carcinomas. I have even found skin malignancies on physicians, their spouses, and their family members.1 These lesions can be easily missed—if you don’t look carefully.

Consider, the following:

- FIGURE 4 illustrates a superficial BCC on the forearm of a physician who was totally unaware of it. (It was detected on “routine” skin examination.)

- FIGURE 5 illustrates a BCC on a patient’s central forehead that, by her history, had been there for many years, and was not of any concern to her. The patient was referred to our office for evaluation of itchy skin on her legs.

- FIGURE 2 illustrates a lesion that, according to the patient, had been on her lip for at least 10—and perhaps even 20—years and was of no concern to her. (It was not the reason for the visit.) Over the years, this patient certainly had numerous primary care and dental visits, but no one “saw” the lesion. Histology confirmed the clinical impression of BCC.

FIGURE 4

Superficial BCC on physician’s forearm

A physician asked for a skin examination, but was totally unaware of this asymptomatic lesion on his dorsal forearm. Once it was identified, he could provide no history about its duration. The lesion had never bled or crusted. Pathology confirmed that it was a superficial basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 5

“Mole” on forehead for many years

This patient was referred for itchy legs. She was unconcerned about a prominent “mole” noted on examination of her forehead, one that she said had been there, unchanged, for many years. Histology confirmed nodular basal cell carcinoma.

- Look, look, and look again, especially at sun-exposed areas (faces, ears, scalps [as hair thins], and dorsal forearms).

- Make sure patients are appropriately gowned no matter what the reason for their visit. Listening to heart and lung sounds and palpating abdomens through overcoats may work for some physicians, but not those interested in finding asymptomatic basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. Melanoma in men is most common on the back; in women, it’s most common on the legs. Seeing these areas requires that they be accessible.

- Biopsy when you’re in doubt. If you see a lesion and it is not recognizable as benign (eg, cherry angioma, seborrheic keratosis, nevus), biopsy it. Let the pathologist determine if it’s benign or malignant. If the lesion is questionable and is in an area that you are uncomfortable biopsying, refer the patient for evaluation and potential biopsy.

Mistake #2: Using insufficient light

As a former family practice academic, I used to preach to residents that they needed to use “light, light, and more light” for evaluation of skin lesions. Despite this, I was often asked to evaluate a patient with a resident who hadn’t even bothered to turn on a goose-neck lamp for illumination.

Even with my current “double bank” daylight fluorescent examination room lighting, it often takes additional (surgical-type) lighting to see the diagnostic features of skin lesions. Without such intense light, it is often impossible to see whether there is pearliness, rolled edges, or fine telangiectasia.

- Use whatever intense source of light you have, whether it’s a goose-neck lamp, a halogen, or a surgical light. If you don’t have at least a portable source of bright light, you are under-equipped for a good skin exam.

Mistake #3: Using insufficient (or no) magnification

I was once examining a patient in a hospital room that had inadequate light, despite my best efforts. So I took out my digital camera with flash and autofocus feature and photographed the lesion. I then looked at the lesion on the camera’s LCD monitor and determined that it was a BCC.

The benefit of the camera was 2-fold: Not only did the flash serve as an instant source of light, but the macro feature also provided magnification. Viewing a magnified digital image on a computer screen also allows unhurried, self “second opinions,” where details can often be ascertained that were not immediately apparent in “real time,” such as rolled edges, telangiectasia, dots, streaks, and subtleties of color.

- Use a hand-held magnifying lens (5X to 10X) routinely during skin exams. They’re not expensive and should be part of every primary care physician’s armamentarium—just like stethoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and reflex hammers.

- Use a digital camera to provide the magnification needed to see details that can be missed clinically. I’m convinced that using a digital camera has made me a better observer—and clinician. Additionally, digital photographs can be stored and compared with histologic results as “self-education.” When purchasing a camera for this purpose, make sure it has a good close-up (macro) feature.

Mistake #4: Assuming that pathology is a perfect science

Most physicians assume that dermatopathologists have a high rate of interrater concordance with diagnoses such as melanoma. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Consider the following:

- As part of a National Institutes of Health consensus conference on melanoma, 8 dermatopathologists considered experts in melanoma were asked to provide 5 slides each. The slides were relabeled and sent to the same 8 dermatopathologists. (Three slides were eliminated.) Their findings: At the extremes, 1 pathologist called 21 cases melanoma and 16 benign, whereas another called 10 melanoma, 26 benign, and one indeterminate.2 (Remember: These were all experts in melanoma.)

- In a study of 30 melanocytic lesion specimens (including Spitzoid lesions), 10 Harvard dermatopathologists evaluated each sample independently of each other. Given 5 diagnostic categories to choose from, in only one case did as many as 6 of the 10 agree on a diagnosis. In all of these cases, there was long-term clinical follow-up, so the biologic behavior of these lesions was known. Some lesions that proved fatal were categorized by most observers as benign (eg, Spitz nevi or atypical Spitz tumors). The converse, reporting benign lesions as melanoma, also occurred.3

So consider this: If this degree of discordance occurs among dermatopathologists, what results could we expect from non-dermatopathologists?

I have personally seen instances where reports of melanoma from non-dermatopathologists did not even report Clark and Breslow staging information (although one could determine Clark staging from reading the body of the report), and reports of dysplastic nevi that were accompanied by recommendations for re-excision with 1 cm margins.

When I have a report from a general pathologist suggesting a potentially worrisome lesion (melanoma, severely dysplastic nevus, [atypical] Spitz nevus), I always suggest to my patients that we get a dermatopathologic second opinion. (I send all my dermatopathology specimens to dermatopathologists, so this applies to patients referred in with prior pathology in hand.)

Sometimes, even the dermatopathologists do not agree on the nature of the lesion. In such cases, I have my “MELTUMP discussion” with patients. That is, I tell patients that we don’t know for sure what it is, and that ultimately only the final lab test—time—will tell us the true nature of the lesion (FIGURE 3).4

- Send all “skin” to a dermatopathologist. You owe it to your patients.

- Send pictures (electronic or hard copy) to the dermatopathologist when the pathology report and clinical picture do not appear to match. While pictures of skin lesions and dermoscopic photographs would most likely be meaningless to general pathologists, they are useful to dermatopathologists. Research has shown that pathologists in various areas of medicine may alter their diagnosis or differential diagnosis when presented with additional clinical information.5

Mistake #5: Freezing neoplasms without a definitive Dx

“We’ll freeze it and if it doesn’t go away, then…”

This approach poses a significant risk to you (medicolegally) and your patient.

While most of the time what I see has been inappropriately frozen first by first-line providers, that is not always the case. Dermatologists also fall into this trap. FIGURE 6 shows a lesion just behind the hairline on the frontoparietal scalp that was frozen by a very good, and reputable, dermatologist. The patient came to me for a second opinion with an “obvious” BCC.

Some clinicians are “thrown off” when a lesion (like the one on this patient) has hair. Some sources6 indicate that BCCs never have hair, but this is patently untrue.

FIGURE 6

This shouldn’t have been frozen

A dermatologist froze this lesion on a patient’s scalp, believing that it was seborrheic keratosis, based on the patient’s history. The patient sought a second opinion, and the lesion (which had hair) was histologically identified as basal cell carcinoma.

- Don’t freeze a lesion when you are unsure; biopsy it. This is especially critical when you consider that cryotherapy is not considered a first-line treatment for BCC, the most common human malignancy. It is better to biopsy, assure the diagnosis, and then provide the appropriate therapy.

Mistake #6: Treating psoriasis with systemic corticosteroids

Plaque psoriasis can, albeit uncommonly, be transformed to pustular psoriasis after the administration of oral or injectable systemic corticosteroids.7 Although this rarely occurs, most experts consider this poor practice and not worth the risk. In addition, some experts note that systemic glucocorticoids are a drug trigger for inducing or exacerbating psoriasis.8

- Avoid systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis, since psoriasis is generally a long-term disease and systemic corticosteroids are a short-term fix. if there is widespread psoriasis and you are not familiar with systemic treatments, refer the patient. If there is localized disease, consider topical treatment options—such as various strengths of corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tazarotene (individually or in combination)—depending on location and plaque thickness.

Mistake #7: Doing shave biopsies on melanocytic lesions

For a melanoma, not only can shaving part way through the vertical dimension of the lesion interfere with staging, it can also hinder the pathologist’s ability to arrive at the correct diagnosis.9

- Do a full-thickness, narrow-margin, fully excisional biopsy when you suspect melanoma. Certainly, there are individuals who are expert at saucerization (deep shave biopsies, often with scalloped, sloping edges that go to the deep reticular dermis) and who can perform biopsies of melanocytic lesions while still obtaining reasonable pathologic staging information.

Mistake #8: Using corticosteroid/antifungal combination products

Corticosteroid/antifungal combination products are generally shunned by dermatologists, although they are used extensively by nondermatologists.9 The difficulty with a preparation like Lotrisone, which contains a class III corticosteroid (betamethasone dipropionate [Diprosone]) and the antifungal clotrimazole, is that it is often used long-term for presumed fungal infection on thin-skinned areas. Unfortunately, though, chronic use in these areas can lead to atrophy and striae (FIGURE 7).

Additionally, corticosteroid is essentially “fungus food.” Majocchi’s granulomas can form because the corticosteroid interferes with clotrimazole’s antifungal effect. Note also that these combination products can suppress fungus sufficiently to render cultures and KOH preparations falsely negative and alter the clinical appearance of psoriasiform dermatitis, interfering with subsequent, accurate diagnosis.

FIGURE 7

Striae after corticosteroid combination therapy

This patient developed striae and atrophy after using a combination high-potency topical corticosteroid/antifungal preparation in a thin-skinned area (proximal medial thigh). It was unclear what the prescriber was treating.

- Consider compounding with miconazole powder and hydrocortisone powder, if a corticosteroid/antifungal combination is necessary (which it rarely is). For example, hydrocortisone 1% or 0.5% ointment can be compounded with miconazole powder for short-term, careful external application, in cases of angular cheilitis.

- Limit your use of a topical corticosteroid for a fungal eruption (if one must be used) to the first few days of treatment. The corticosteroid class should be appropriate to the site of application.9

- Counsel your patients about the risks of using topical corticosteroids on thinskinned areas for more than a few days (few weeks, maximum). On the face, corticosteroids can cause rosacea and perioral dermatitis, as well as “rebound” vasodilation. Thus, topical corticosteroids should be used with great caution—and generally as a last resort—for chronic facial dermatoses.

Mistake #9: Corticosteroid underdosing and undercounseling

It’s not uncommon during the warm weather months for me to see patients who are near finishing a Medrol Dosepak that was prescribed by their primary care physicians for a case of contact dermatitis (eg, poison ivy). They come to me because the eruption has returned and it is “as bad as ever.”

Underdosing. Medrol Dosepaks are generally underpowered (too low a dosage) and too short a course.7,10,11

Undercounseling. Patients don’t always realize that contact dermatitis may actually last for 3 weeks or longer. They may also mistakenly believe that systemic treatment will get them through the whole episode (rather than the worst part).

- Design your own prednisone taper for when such tapers are needed. You might even have the prescription, with taper, prefilled on paper for signature. for significant allergic contact dermatitis, the taper may last 2 weeks.

- Dispel myths. Assure patients that by taking a thorough soap shower (and laundering the clothing they were wearing), they will remove all of the oil responsible for the disease.

- Limit your use of injectable corticosteroids. There is little need for injectable corticosteroids in cases of contact dermatitis. Oral corticosteroids work just as well, can be more easily titered based on response, and pose no injection risk of tissue atrophy or abscess formation.9

Mistake #10: Requiring red flags in both history and exam

Skin diagnosis is an “or” game—not an “and” game. By that I mean: If either the history (eg, rapid change, bleeding, crusting, nonhealing ulcer) or the examination is worrisome, biopsy. Even dermoscopy can be completely reassuring with biopsy yielding a melanoma.12 Note, too, our earlier examples of patients with suspect examinations who gave reassuring histories of lesions that had been present for many years. Either a worrisome history or a suspect examination is sufficient for concern. Remember, in general, the worst-case scenario from a biopsy is a scar; from a missed melanoma, an autopsy report.

- Get back to basics. Look carefully at your patient’s skin—even if it’s not the reason for the visit. Take a moment to ask your patient: Do you have any changing lesions or is there anything on your skin that is scaly, bleeding, or crusting? Doing so will cut down on the number of patients who ultimately learn that the lesion that’s “always been there,” and that “didn’t worry the other doctors” is actually a skin cancer.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, 1400 E 2nd St, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Fox GN, Mehregan DR. A new papule and “age spots.” J Fam Pract 2007;56:278-282.

2. Farmer ER, Gonin R, Hanna MP. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma and melanocytic nevi between expert pathologists. Hum Pathol 1996;27:528-531.

3. Barnhill RL, Argenyi ZB, From L, et al. Atypical Spitz nevi/tumors: lack of consensus for diagnosis, discrimination from melanoma, and prediction of outcome. Hum Pathol 1999;30:513-520.

4. Elder DE, Xu X. The approach to the patient with a difficult melanocytic lesion. Pathology 2004;36:428-434.

5. McBroom HM, Ramsay AD. The clinicopathological meeting. A means of auditing diagnostic performance. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:75-80.

6. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004.

7. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004.

8. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

9. Edwards L. Dermatology in Emergency Care. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

10. Brodell RT, Williams L. Taking the itch out of poison ivy. Postgrad Med 1999;106:69-70.

11. Hall JC. Dermatologic allergy. In: Hall JC, ed. Sauer’s Manual of Skin Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:82.

12. Braun RP, Gaide O, Skaria AM, Kopf AW, Saurat JH, Marghoob AA. Exclusively benign dermoscopic pattern in a patient with acral melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:1213-1215.

1. Fox GN, Mehregan DR. A new papule and “age spots.” J Fam Pract 2007;56:278-282.

2. Farmer ER, Gonin R, Hanna MP. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma and melanocytic nevi between expert pathologists. Hum Pathol 1996;27:528-531.

3. Barnhill RL, Argenyi ZB, From L, et al. Atypical Spitz nevi/tumors: lack of consensus for diagnosis, discrimination from melanoma, and prediction of outcome. Hum Pathol 1999;30:513-520.

4. Elder DE, Xu X. The approach to the patient with a difficult melanocytic lesion. Pathology 2004;36:428-434.

5. McBroom HM, Ramsay AD. The clinicopathological meeting. A means of auditing diagnostic performance. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:75-80.

6. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004.

7. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004.

8. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

9. Edwards L. Dermatology in Emergency Care. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

10. Brodell RT, Williams L. Taking the itch out of poison ivy. Postgrad Med 1999;106:69-70.

11. Hall JC. Dermatologic allergy. In: Hall JC, ed. Sauer’s Manual of Skin Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:82.

12. Braun RP, Gaide O, Skaria AM, Kopf AW, Saurat JH, Marghoob AA. Exclusively benign dermoscopic pattern in a patient with acral melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:1213-1215.