User login

How I solved my e-prescribing dilemma

Even with government incentives, I physicians have been slow to make the leap to electronic medical records (EMR) and full electronic prescribing (e-prescribing). My transition to e-prescribing evolved over about a decade, and I was a satisfied e-prescriber—for a while.

Around 2000, I began writing electronic prescriptions using iScribe for Palm handhelds.1 The final transition to full e-prescribing required only a WiFi connection in the office for use with my Palm, and hitting Send to submit the prescription to the pharmacy. iScribe was user friendly and fast. It eliminated pharmacy “callbacks, “ provided printed receipts for charting, and maintained a record of each prescription on the Palm, filed under the patient’s name. A full prescription history for each patient archived on the Palm reduced the need to pull charts for medication questions.

A rude surprise

Then iScribe was acquired by another company whose e-prescribing product, in my opinion, lengthened patient encounters because it required several additional steps to complete a prescription. This was unacceptable to me, and returning to handwritten prescriptions was out of the question. I needed a better solution.

I was disinclined to invest in another e-prescribing product whose tenure could end as abruptly as iScribe’s had. To wit: I recently read about another user-friendly, well-supported medical software program that was scooped up by a larger company selling less functional and more expensive products (while charging for a costly conversion of existing records and delivering poorer customer service).2 And e-prescribing in general has received mixed reviews.3

I briefly considered designing my own prescription writer. A full-featured writer using a relational database, such as Microsoft Access, would be ideal. But developing it would be daunting without software-specific training. The same would be true for spreadsheet software. Adobe Acrobat or word processors with directories or hyperlinks or search functions didn’t seem appropriate.

A welcome surprise

Microsoft Office 2010 software for PC and Mac platforms now includes OneNote, a program new to me. (Price at Costco for Office Home and Student, September 2010, was $119.) OneNote (in which I have no vested interest) is an “electronic notebook” program—a digital version of the multisubject, tabbed binders we all used in school. The user creates tabs, which appear across the top of the notebook interface. Each tab can accommodate as many pages as the user desires, just as in the sections of a paper notebook (FIGURE 1). In OneNote, each page has a title, and the title appears on the page tab on the right side of the screen (left side is an option). Several layers of subpages are also available for each page, similar to subdirectories in a computerized filing system.

FIGURE 1

Tabbed sections

OneNote’s Tabs are visible across the top. Most of the pages on the right side are obscured in this view by the search results window.

First tab: Summary sheet of patient “problems”

Since 2005, my practice has been limited to skin disease and it has been my custom to create paper “problem lists” as a handy method of tracking each patient’s malignancy types, dates, and anatomic locations. I decided to make these lists electronic, using OneNote (FIGURE 2). OneNote allows default templates, whereby clicking on New Page creates a fully formatted page. I used the template to create a derm summary sheet tab. Under that, I created an electronic page for each of the practice’s patients with a malignancy.

These patient pages are rapidly accessible with OneNote’s search box. As each additional letter is entered, the search feature narrows the possible matches. Usually, entering the first couple of letters of the last name presents the desired match in the search window. I then click on the patient’s name and hit Print; the summary is produced faster than the time it would take to find the information in an alphabetized paper notebook.

The advantage of an electronic summary sheet is that it can be updated and printed at each visit. Electronic summary sheets can be designed in any format—eg, a main page with Problems, Medications, Medication Allergies, Social History, Family History, etc, and a second page with a Health Maintenance flow sheet, or whatever makes sense for the clinician’s practice.

With OneNote, tables, graphics, and text with various fonts can be placed anywhere on the page, as can elements created with drawing tools. Pages can be any size: 3x5 card, letter, legal, or endless (like a Web page). OneNote supports “copy and paste” and “drag and drop” from other programs, as well as hyperlinks to documents outside OneNote.

The user can easily design a variety of templates for use in each tab, simply by designing a page and designating a template. One template can be set as the default for that tab. For example, when I click New Page in the Summary tab, a new summary form appears in that section. Pages can be deleted, copied, or moved within and between sections, just as in a word processing program.

FIGURE 2

Summary sheet

Each patient has a page (identifying information at right is covered) that lists his or her chronic/acute problems, as well as malignancies. One can locate the proper page by typing the first few letters of the patient’s last name in the search field.

A second tab for prescriptions

I decided to add a second tab to my notebook: Prescriptions. I designed a prescription template and set that as my default New Page for the prescription section. I created a new page for each of my common prescriptions—eg, doxycycline, minocycline, various topical acne preparations. OneNote’s search function at the top of the pages section is nearly instantaneous and shows all possible matches for a string of characters. Entering “tre” will show all matches with “tretinoin. “ It’s easy, then, to select the preparation of interest, hit Print, and have a printed prescription in seconds. For even greater efficiency, I have created new prescription pages for multiple medications I often use in combination—eg, a morning antimicrobial and an evening retinoid for acne, or compounds such as magic mouthwash (FIGURE 3).

Our office check-in process includes producing printed sticky labels with a patient’s name and address and the current date, which we can affix to things like pictures and pathology slips. So I designed my prescription blank to accommodate such labels. I print prescriptions from my wireless notebook computer to a wireless printer. The nurse affixes a label, I sign the document, and in seconds the patient has a detailed, legible prescription. The only disadvantage with this system is that unlike iScribe, I cannot look up a patient’s prescription history electronically because there is no electronically filed copy saved with the patient’s name. One option would be to enter every patient on a page and put prescriptions as subpages under the patient’s page. But that is more work than I want to do in patient exam rooms during a visit. Instead, I print 2 copies of each prescription, one of which goes into the paper chart.

I populated my Prescriptions tab with my prescription “favorites” before going live. But this can also be done “on the fly. “ You simply enter a new prescription as the need arises. OneNote automatically saves the prescription for future use (unless it’s intentionally deleted).

To produce new prescriptions, I set the Prescription blank as the default template. I click New Page and a blank prescription form appears. So, let’s say that lidocaine gel is not in the prescriber. I search “lido, “ and the ointment and transdermal formulations that have already been entered come up. I click New Page, a blank prescription form appears, and I type the details of the prescription (lidocaine gel 2%, dispense 30 grams, apply 30 to 60 minutes before procedure, refill zero). This prescription is saved automatically and will be available the next time I search “lido. “ Alternatively, an existing prescription can be copied and easily modified, as in copying a “cream” prescription and changing to “ointment” in the copy so both are available for future use.

All sorts of variations are possible: “endocarditis prophylaxis” options could be entered as a list on one prescription form. Before the list is printed, the user could simply check the desired option for that patient. Because OneNote saves all changes automatically, any changes made to the default prescriptions (eg, choosing to give a medication once daily rather than the default of twice daily) are saved automatically. When I make any custom changes, I use the Undo button, which I placed on my Quick Access Toolbar, to easily return to my preferred default status.

FIGURE 3

Prescription page for multiple medications

Medications commonly used together can be combined on a single prescription form. Additional information may be included (and discussed in advance with patients), to reduce formulary callback and preauthorization issues. Alphabetizing the prescriptions is unnecessary, given that the robust search function matches even partial words.

A third tab for patient education

After the success with the Summary sheets and Prescriptions tabs, I added a Patient Ed tab (FIGURE 4). I use handouts liberally to reinforce discussions, to give directions for medication use (eg, retinoids, imiquimod, fluorouracil, permethrin, prednisone), and to educate patients about diseases (eg, dysplastic nevi, melanoma, scabies). Most of this information resides on my computer, and OneNote allows me to rapidly locate and print the documents. I copy the links to patient education files onto corresponding individual OneNote pages, organized by the handouts’ identifying key words.

For example, for the isotretinoin-inflammatory bowel disease information sheet, I created a page called “Isotretinoin - Inflammatory Bowel Disease” in the Patient Education tab. That page contains a hyperlink to the desired document on my computer. The original document can be updated as new information becomes available, and OneNote will always link to the current version. For less commonly used handouts, I can enter key title words in the search box, click on the appropriate page, and print the document.

Because the printer is in the hall 2 steps from each exam room, I can do that faster than the nurse can find these documents in our paper system. This is particularly useful if the information on the possible link between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease is missing from our isotretinoin packet.

FIGURE 4

Patient education tab

OneNote can be used as an indexing aid for patient education materials by simply dragging and dropping into it the links to “original” patient education documents. By clicking on this link, one can go to the information that resides elsewhere, and print out the material for the patient.

Many advantages with this new system

With OneNote, I have elements of a mini-electronic record with summary sheets for patients with malignancies, prescription writing, and patient handouts. In addition, I will not lose this system in a corporate buyout or be charged exorbitant fees to transfer records. Tabs can be password protected for security, and all pages under a tab can be saved in Adobe Acrobat, Microsoft Word, and OneNote formats. Those features help assure security and portability. (This system does not, however, qualify users for government incentives, as it lacks certain functions that are available with a true EMR.)

True e-prescribing—which, for me, included entering patient demographics and offered electronic access to my prescribing history for each patient—is usually an intermediary step for those moving toward full EMR implementation. Using OneNote, I carry a laptop/notebook room to room and print a lot of patient information handouts that otherwise would have to be retrieved from elsewhere.

As a trial, I used the OneNote system along with iScribe’s replacement e-prescribing product for several weeks. My OneNote system was faster. Now, only when patients specifically request e-prescriptions do I use the iScribe replacement product, which, after the corporate merger, has been continued at no charge for 2 to 3 years for existing users. (E-prescribing for Medicare patients at least 25 times in 2011 will qualify users for the Medicare incentive bonus.)

Because the “computer” portion of patient encounters usually occurs at the end of the visit, it does not interfere with the patient-physician relationship. Additionally, my average patient has already been “teched” with a digital scale, digital blood pressure cuff, and digital camera, so a computer is probably one of the more familiar pieces in the technoscape.

OneNote has become a powerful ally in my clinical practice. I thought I had everything I needed with Word, Excel, and Acrobat. But I’m glad I opened OneNote out of curiosity. It’s not only helped me to modernize my patient “problem lists, “ but it’s proven to be the solution to my e-prescribing dilemma.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 E. 2nd Street, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Fox GN. Electronic prescribing: drug dealing twenty-first century style. In: Strayer SM, Reynolds PL, Ebell MH, eds. Handhelds in Medicine: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.

2. Levine N. Before implementing EMRs, heed words of warning. Dermatology Times. May 2010. Available at: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/Before-implementing-EMRs-heedwords-of-warning/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/666763. Accessed May 28, 2010.

3. Nash K. E-prescribing: a boon or a bane to dermatology practices? Dermatology Times. May 2010. Available at: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/E-prescribing-a-boon-or-a-bane-to-dermatology-prac/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/666779. Accessed May 28, 2010.

Even with government incentives, I physicians have been slow to make the leap to electronic medical records (EMR) and full electronic prescribing (e-prescribing). My transition to e-prescribing evolved over about a decade, and I was a satisfied e-prescriber—for a while.

Around 2000, I began writing electronic prescriptions using iScribe for Palm handhelds.1 The final transition to full e-prescribing required only a WiFi connection in the office for use with my Palm, and hitting Send to submit the prescription to the pharmacy. iScribe was user friendly and fast. It eliminated pharmacy “callbacks, “ provided printed receipts for charting, and maintained a record of each prescription on the Palm, filed under the patient’s name. A full prescription history for each patient archived on the Palm reduced the need to pull charts for medication questions.

A rude surprise

Then iScribe was acquired by another company whose e-prescribing product, in my opinion, lengthened patient encounters because it required several additional steps to complete a prescription. This was unacceptable to me, and returning to handwritten prescriptions was out of the question. I needed a better solution.

I was disinclined to invest in another e-prescribing product whose tenure could end as abruptly as iScribe’s had. To wit: I recently read about another user-friendly, well-supported medical software program that was scooped up by a larger company selling less functional and more expensive products (while charging for a costly conversion of existing records and delivering poorer customer service).2 And e-prescribing in general has received mixed reviews.3

I briefly considered designing my own prescription writer. A full-featured writer using a relational database, such as Microsoft Access, would be ideal. But developing it would be daunting without software-specific training. The same would be true for spreadsheet software. Adobe Acrobat or word processors with directories or hyperlinks or search functions didn’t seem appropriate.

A welcome surprise

Microsoft Office 2010 software for PC and Mac platforms now includes OneNote, a program new to me. (Price at Costco for Office Home and Student, September 2010, was $119.) OneNote (in which I have no vested interest) is an “electronic notebook” program—a digital version of the multisubject, tabbed binders we all used in school. The user creates tabs, which appear across the top of the notebook interface. Each tab can accommodate as many pages as the user desires, just as in the sections of a paper notebook (FIGURE 1). In OneNote, each page has a title, and the title appears on the page tab on the right side of the screen (left side is an option). Several layers of subpages are also available for each page, similar to subdirectories in a computerized filing system.

FIGURE 1

Tabbed sections

OneNote’s Tabs are visible across the top. Most of the pages on the right side are obscured in this view by the search results window.

First tab: Summary sheet of patient “problems”

Since 2005, my practice has been limited to skin disease and it has been my custom to create paper “problem lists” as a handy method of tracking each patient’s malignancy types, dates, and anatomic locations. I decided to make these lists electronic, using OneNote (FIGURE 2). OneNote allows default templates, whereby clicking on New Page creates a fully formatted page. I used the template to create a derm summary sheet tab. Under that, I created an electronic page for each of the practice’s patients with a malignancy.

These patient pages are rapidly accessible with OneNote’s search box. As each additional letter is entered, the search feature narrows the possible matches. Usually, entering the first couple of letters of the last name presents the desired match in the search window. I then click on the patient’s name and hit Print; the summary is produced faster than the time it would take to find the information in an alphabetized paper notebook.

The advantage of an electronic summary sheet is that it can be updated and printed at each visit. Electronic summary sheets can be designed in any format—eg, a main page with Problems, Medications, Medication Allergies, Social History, Family History, etc, and a second page with a Health Maintenance flow sheet, or whatever makes sense for the clinician’s practice.

With OneNote, tables, graphics, and text with various fonts can be placed anywhere on the page, as can elements created with drawing tools. Pages can be any size: 3x5 card, letter, legal, or endless (like a Web page). OneNote supports “copy and paste” and “drag and drop” from other programs, as well as hyperlinks to documents outside OneNote.

The user can easily design a variety of templates for use in each tab, simply by designing a page and designating a template. One template can be set as the default for that tab. For example, when I click New Page in the Summary tab, a new summary form appears in that section. Pages can be deleted, copied, or moved within and between sections, just as in a word processing program.

FIGURE 2

Summary sheet

Each patient has a page (identifying information at right is covered) that lists his or her chronic/acute problems, as well as malignancies. One can locate the proper page by typing the first few letters of the patient’s last name in the search field.

A second tab for prescriptions

I decided to add a second tab to my notebook: Prescriptions. I designed a prescription template and set that as my default New Page for the prescription section. I created a new page for each of my common prescriptions—eg, doxycycline, minocycline, various topical acne preparations. OneNote’s search function at the top of the pages section is nearly instantaneous and shows all possible matches for a string of characters. Entering “tre” will show all matches with “tretinoin. “ It’s easy, then, to select the preparation of interest, hit Print, and have a printed prescription in seconds. For even greater efficiency, I have created new prescription pages for multiple medications I often use in combination—eg, a morning antimicrobial and an evening retinoid for acne, or compounds such as magic mouthwash (FIGURE 3).

Our office check-in process includes producing printed sticky labels with a patient’s name and address and the current date, which we can affix to things like pictures and pathology slips. So I designed my prescription blank to accommodate such labels. I print prescriptions from my wireless notebook computer to a wireless printer. The nurse affixes a label, I sign the document, and in seconds the patient has a detailed, legible prescription. The only disadvantage with this system is that unlike iScribe, I cannot look up a patient’s prescription history electronically because there is no electronically filed copy saved with the patient’s name. One option would be to enter every patient on a page and put prescriptions as subpages under the patient’s page. But that is more work than I want to do in patient exam rooms during a visit. Instead, I print 2 copies of each prescription, one of which goes into the paper chart.

I populated my Prescriptions tab with my prescription “favorites” before going live. But this can also be done “on the fly. “ You simply enter a new prescription as the need arises. OneNote automatically saves the prescription for future use (unless it’s intentionally deleted).

To produce new prescriptions, I set the Prescription blank as the default template. I click New Page and a blank prescription form appears. So, let’s say that lidocaine gel is not in the prescriber. I search “lido, “ and the ointment and transdermal formulations that have already been entered come up. I click New Page, a blank prescription form appears, and I type the details of the prescription (lidocaine gel 2%, dispense 30 grams, apply 30 to 60 minutes before procedure, refill zero). This prescription is saved automatically and will be available the next time I search “lido. “ Alternatively, an existing prescription can be copied and easily modified, as in copying a “cream” prescription and changing to “ointment” in the copy so both are available for future use.

All sorts of variations are possible: “endocarditis prophylaxis” options could be entered as a list on one prescription form. Before the list is printed, the user could simply check the desired option for that patient. Because OneNote saves all changes automatically, any changes made to the default prescriptions (eg, choosing to give a medication once daily rather than the default of twice daily) are saved automatically. When I make any custom changes, I use the Undo button, which I placed on my Quick Access Toolbar, to easily return to my preferred default status.

FIGURE 3

Prescription page for multiple medications

Medications commonly used together can be combined on a single prescription form. Additional information may be included (and discussed in advance with patients), to reduce formulary callback and preauthorization issues. Alphabetizing the prescriptions is unnecessary, given that the robust search function matches even partial words.

A third tab for patient education

After the success with the Summary sheets and Prescriptions tabs, I added a Patient Ed tab (FIGURE 4). I use handouts liberally to reinforce discussions, to give directions for medication use (eg, retinoids, imiquimod, fluorouracil, permethrin, prednisone), and to educate patients about diseases (eg, dysplastic nevi, melanoma, scabies). Most of this information resides on my computer, and OneNote allows me to rapidly locate and print the documents. I copy the links to patient education files onto corresponding individual OneNote pages, organized by the handouts’ identifying key words.

For example, for the isotretinoin-inflammatory bowel disease information sheet, I created a page called “Isotretinoin - Inflammatory Bowel Disease” in the Patient Education tab. That page contains a hyperlink to the desired document on my computer. The original document can be updated as new information becomes available, and OneNote will always link to the current version. For less commonly used handouts, I can enter key title words in the search box, click on the appropriate page, and print the document.

Because the printer is in the hall 2 steps from each exam room, I can do that faster than the nurse can find these documents in our paper system. This is particularly useful if the information on the possible link between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease is missing from our isotretinoin packet.

FIGURE 4

Patient education tab

OneNote can be used as an indexing aid for patient education materials by simply dragging and dropping into it the links to “original” patient education documents. By clicking on this link, one can go to the information that resides elsewhere, and print out the material for the patient.

Many advantages with this new system

With OneNote, I have elements of a mini-electronic record with summary sheets for patients with malignancies, prescription writing, and patient handouts. In addition, I will not lose this system in a corporate buyout or be charged exorbitant fees to transfer records. Tabs can be password protected for security, and all pages under a tab can be saved in Adobe Acrobat, Microsoft Word, and OneNote formats. Those features help assure security and portability. (This system does not, however, qualify users for government incentives, as it lacks certain functions that are available with a true EMR.)

True e-prescribing—which, for me, included entering patient demographics and offered electronic access to my prescribing history for each patient—is usually an intermediary step for those moving toward full EMR implementation. Using OneNote, I carry a laptop/notebook room to room and print a lot of patient information handouts that otherwise would have to be retrieved from elsewhere.

As a trial, I used the OneNote system along with iScribe’s replacement e-prescribing product for several weeks. My OneNote system was faster. Now, only when patients specifically request e-prescriptions do I use the iScribe replacement product, which, after the corporate merger, has been continued at no charge for 2 to 3 years for existing users. (E-prescribing for Medicare patients at least 25 times in 2011 will qualify users for the Medicare incentive bonus.)

Because the “computer” portion of patient encounters usually occurs at the end of the visit, it does not interfere with the patient-physician relationship. Additionally, my average patient has already been “teched” with a digital scale, digital blood pressure cuff, and digital camera, so a computer is probably one of the more familiar pieces in the technoscape.

OneNote has become a powerful ally in my clinical practice. I thought I had everything I needed with Word, Excel, and Acrobat. But I’m glad I opened OneNote out of curiosity. It’s not only helped me to modernize my patient “problem lists, “ but it’s proven to be the solution to my e-prescribing dilemma.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 E. 2nd Street, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

Even with government incentives, I physicians have been slow to make the leap to electronic medical records (EMR) and full electronic prescribing (e-prescribing). My transition to e-prescribing evolved over about a decade, and I was a satisfied e-prescriber—for a while.

Around 2000, I began writing electronic prescriptions using iScribe for Palm handhelds.1 The final transition to full e-prescribing required only a WiFi connection in the office for use with my Palm, and hitting Send to submit the prescription to the pharmacy. iScribe was user friendly and fast. It eliminated pharmacy “callbacks, “ provided printed receipts for charting, and maintained a record of each prescription on the Palm, filed under the patient’s name. A full prescription history for each patient archived on the Palm reduced the need to pull charts for medication questions.

A rude surprise

Then iScribe was acquired by another company whose e-prescribing product, in my opinion, lengthened patient encounters because it required several additional steps to complete a prescription. This was unacceptable to me, and returning to handwritten prescriptions was out of the question. I needed a better solution.

I was disinclined to invest in another e-prescribing product whose tenure could end as abruptly as iScribe’s had. To wit: I recently read about another user-friendly, well-supported medical software program that was scooped up by a larger company selling less functional and more expensive products (while charging for a costly conversion of existing records and delivering poorer customer service).2 And e-prescribing in general has received mixed reviews.3

I briefly considered designing my own prescription writer. A full-featured writer using a relational database, such as Microsoft Access, would be ideal. But developing it would be daunting without software-specific training. The same would be true for spreadsheet software. Adobe Acrobat or word processors with directories or hyperlinks or search functions didn’t seem appropriate.

A welcome surprise

Microsoft Office 2010 software for PC and Mac platforms now includes OneNote, a program new to me. (Price at Costco for Office Home and Student, September 2010, was $119.) OneNote (in which I have no vested interest) is an “electronic notebook” program—a digital version of the multisubject, tabbed binders we all used in school. The user creates tabs, which appear across the top of the notebook interface. Each tab can accommodate as many pages as the user desires, just as in the sections of a paper notebook (FIGURE 1). In OneNote, each page has a title, and the title appears on the page tab on the right side of the screen (left side is an option). Several layers of subpages are also available for each page, similar to subdirectories in a computerized filing system.

FIGURE 1

Tabbed sections

OneNote’s Tabs are visible across the top. Most of the pages on the right side are obscured in this view by the search results window.

First tab: Summary sheet of patient “problems”

Since 2005, my practice has been limited to skin disease and it has been my custom to create paper “problem lists” as a handy method of tracking each patient’s malignancy types, dates, and anatomic locations. I decided to make these lists electronic, using OneNote (FIGURE 2). OneNote allows default templates, whereby clicking on New Page creates a fully formatted page. I used the template to create a derm summary sheet tab. Under that, I created an electronic page for each of the practice’s patients with a malignancy.

These patient pages are rapidly accessible with OneNote’s search box. As each additional letter is entered, the search feature narrows the possible matches. Usually, entering the first couple of letters of the last name presents the desired match in the search window. I then click on the patient’s name and hit Print; the summary is produced faster than the time it would take to find the information in an alphabetized paper notebook.

The advantage of an electronic summary sheet is that it can be updated and printed at each visit. Electronic summary sheets can be designed in any format—eg, a main page with Problems, Medications, Medication Allergies, Social History, Family History, etc, and a second page with a Health Maintenance flow sheet, or whatever makes sense for the clinician’s practice.

With OneNote, tables, graphics, and text with various fonts can be placed anywhere on the page, as can elements created with drawing tools. Pages can be any size: 3x5 card, letter, legal, or endless (like a Web page). OneNote supports “copy and paste” and “drag and drop” from other programs, as well as hyperlinks to documents outside OneNote.

The user can easily design a variety of templates for use in each tab, simply by designing a page and designating a template. One template can be set as the default for that tab. For example, when I click New Page in the Summary tab, a new summary form appears in that section. Pages can be deleted, copied, or moved within and between sections, just as in a word processing program.

FIGURE 2

Summary sheet

Each patient has a page (identifying information at right is covered) that lists his or her chronic/acute problems, as well as malignancies. One can locate the proper page by typing the first few letters of the patient’s last name in the search field.

A second tab for prescriptions

I decided to add a second tab to my notebook: Prescriptions. I designed a prescription template and set that as my default New Page for the prescription section. I created a new page for each of my common prescriptions—eg, doxycycline, minocycline, various topical acne preparations. OneNote’s search function at the top of the pages section is nearly instantaneous and shows all possible matches for a string of characters. Entering “tre” will show all matches with “tretinoin. “ It’s easy, then, to select the preparation of interest, hit Print, and have a printed prescription in seconds. For even greater efficiency, I have created new prescription pages for multiple medications I often use in combination—eg, a morning antimicrobial and an evening retinoid for acne, or compounds such as magic mouthwash (FIGURE 3).

Our office check-in process includes producing printed sticky labels with a patient’s name and address and the current date, which we can affix to things like pictures and pathology slips. So I designed my prescription blank to accommodate such labels. I print prescriptions from my wireless notebook computer to a wireless printer. The nurse affixes a label, I sign the document, and in seconds the patient has a detailed, legible prescription. The only disadvantage with this system is that unlike iScribe, I cannot look up a patient’s prescription history electronically because there is no electronically filed copy saved with the patient’s name. One option would be to enter every patient on a page and put prescriptions as subpages under the patient’s page. But that is more work than I want to do in patient exam rooms during a visit. Instead, I print 2 copies of each prescription, one of which goes into the paper chart.

I populated my Prescriptions tab with my prescription “favorites” before going live. But this can also be done “on the fly. “ You simply enter a new prescription as the need arises. OneNote automatically saves the prescription for future use (unless it’s intentionally deleted).

To produce new prescriptions, I set the Prescription blank as the default template. I click New Page and a blank prescription form appears. So, let’s say that lidocaine gel is not in the prescriber. I search “lido, “ and the ointment and transdermal formulations that have already been entered come up. I click New Page, a blank prescription form appears, and I type the details of the prescription (lidocaine gel 2%, dispense 30 grams, apply 30 to 60 minutes before procedure, refill zero). This prescription is saved automatically and will be available the next time I search “lido. “ Alternatively, an existing prescription can be copied and easily modified, as in copying a “cream” prescription and changing to “ointment” in the copy so both are available for future use.

All sorts of variations are possible: “endocarditis prophylaxis” options could be entered as a list on one prescription form. Before the list is printed, the user could simply check the desired option for that patient. Because OneNote saves all changes automatically, any changes made to the default prescriptions (eg, choosing to give a medication once daily rather than the default of twice daily) are saved automatically. When I make any custom changes, I use the Undo button, which I placed on my Quick Access Toolbar, to easily return to my preferred default status.

FIGURE 3

Prescription page for multiple medications

Medications commonly used together can be combined on a single prescription form. Additional information may be included (and discussed in advance with patients), to reduce formulary callback and preauthorization issues. Alphabetizing the prescriptions is unnecessary, given that the robust search function matches even partial words.

A third tab for patient education

After the success with the Summary sheets and Prescriptions tabs, I added a Patient Ed tab (FIGURE 4). I use handouts liberally to reinforce discussions, to give directions for medication use (eg, retinoids, imiquimod, fluorouracil, permethrin, prednisone), and to educate patients about diseases (eg, dysplastic nevi, melanoma, scabies). Most of this information resides on my computer, and OneNote allows me to rapidly locate and print the documents. I copy the links to patient education files onto corresponding individual OneNote pages, organized by the handouts’ identifying key words.

For example, for the isotretinoin-inflammatory bowel disease information sheet, I created a page called “Isotretinoin - Inflammatory Bowel Disease” in the Patient Education tab. That page contains a hyperlink to the desired document on my computer. The original document can be updated as new information becomes available, and OneNote will always link to the current version. For less commonly used handouts, I can enter key title words in the search box, click on the appropriate page, and print the document.

Because the printer is in the hall 2 steps from each exam room, I can do that faster than the nurse can find these documents in our paper system. This is particularly useful if the information on the possible link between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease is missing from our isotretinoin packet.

FIGURE 4

Patient education tab

OneNote can be used as an indexing aid for patient education materials by simply dragging and dropping into it the links to “original” patient education documents. By clicking on this link, one can go to the information that resides elsewhere, and print out the material for the patient.

Many advantages with this new system

With OneNote, I have elements of a mini-electronic record with summary sheets for patients with malignancies, prescription writing, and patient handouts. In addition, I will not lose this system in a corporate buyout or be charged exorbitant fees to transfer records. Tabs can be password protected for security, and all pages under a tab can be saved in Adobe Acrobat, Microsoft Word, and OneNote formats. Those features help assure security and portability. (This system does not, however, qualify users for government incentives, as it lacks certain functions that are available with a true EMR.)

True e-prescribing—which, for me, included entering patient demographics and offered electronic access to my prescribing history for each patient—is usually an intermediary step for those moving toward full EMR implementation. Using OneNote, I carry a laptop/notebook room to room and print a lot of patient information handouts that otherwise would have to be retrieved from elsewhere.

As a trial, I used the OneNote system along with iScribe’s replacement e-prescribing product for several weeks. My OneNote system was faster. Now, only when patients specifically request e-prescriptions do I use the iScribe replacement product, which, after the corporate merger, has been continued at no charge for 2 to 3 years for existing users. (E-prescribing for Medicare patients at least 25 times in 2011 will qualify users for the Medicare incentive bonus.)

Because the “computer” portion of patient encounters usually occurs at the end of the visit, it does not interfere with the patient-physician relationship. Additionally, my average patient has already been “teched” with a digital scale, digital blood pressure cuff, and digital camera, so a computer is probably one of the more familiar pieces in the technoscape.

OneNote has become a powerful ally in my clinical practice. I thought I had everything I needed with Word, Excel, and Acrobat. But I’m glad I opened OneNote out of curiosity. It’s not only helped me to modernize my patient “problem lists, “ but it’s proven to be the solution to my e-prescribing dilemma.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 E. 2nd Street, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Fox GN. Electronic prescribing: drug dealing twenty-first century style. In: Strayer SM, Reynolds PL, Ebell MH, eds. Handhelds in Medicine: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.

2. Levine N. Before implementing EMRs, heed words of warning. Dermatology Times. May 2010. Available at: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/Before-implementing-EMRs-heedwords-of-warning/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/666763. Accessed May 28, 2010.

3. Nash K. E-prescribing: a boon or a bane to dermatology practices? Dermatology Times. May 2010. Available at: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/E-prescribing-a-boon-or-a-bane-to-dermatology-prac/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/666779. Accessed May 28, 2010.

1. Fox GN. Electronic prescribing: drug dealing twenty-first century style. In: Strayer SM, Reynolds PL, Ebell MH, eds. Handhelds in Medicine: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.

2. Levine N. Before implementing EMRs, heed words of warning. Dermatology Times. May 2010. Available at: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/Before-implementing-EMRs-heedwords-of-warning/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/666763. Accessed May 28, 2010.

3. Nash K. E-prescribing: a boon or a bane to dermatology practices? Dermatology Times. May 2010. Available at: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/E-prescribing-a-boon-or-a-bane-to-dermatology-prac/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/666779. Accessed May 28, 2010.

An aid for spotting basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy, but it can still be a tricky and difficult diagnosis even in the most experienced hands. Many BCCs exhibit only some of the defining clinical characteristics, and even when these findings are present, they can be hard to detect without excellent background and oblique lighting and handheld magnification that is 5-power or greater.

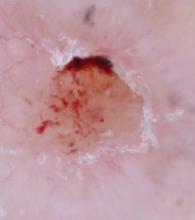

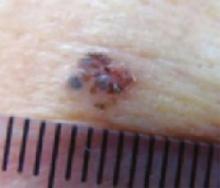

Most clinicians are familiar with classic BCC characteristics of pearliness, rolled edges, telangiectasia, bleeding, and crusting. However, the telangiectasias may be so fine that they are difficult or impossible to see, even with excellent lighting and magnification. FIGURE 1A illustrates a histologically verified nodular BCC with telangiectasias that are not readily visible, even with camera macro magnification.

Some BCC papules or plaques lack the classic rolled edges, even when viewed with oblique lighting and magnification. Some lesions may be more scaly than pearly, and others do not bleed and crust until later in their clinical course. With such variation in clinical presentation, all possible clues to BCC are welcome.

Dark dots: Connecting them to BCC

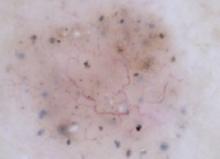

One underappreciated sign that may help with the diagnosis of BCC is the “dark dot sign.”1,2 Dermoscopists are familiar with patterns of pigmentation associated with BCCs, and introductory dermoscopy texts contain pictures of these patterns (blue/blue-gray blotches, maple leaf structures, and spoke-wheel structures).3,4 What is less well known is that this pigmentation may be visible on routine skin examination as “dark dots”—blue, gray, black, or a combination thereof, such as blue-gray. When visible clinically, these dark dots may bolster one’s confidence in the diagnosis—or, in my experience, occasionally even be the best visible hint for a tentative diagnosis of BCC.

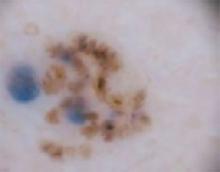

Case in point. During a routine skin examination of a patient’s back, I identified an asymptomatic lesion the patient was unaware of, exhibiting no bleeding or crusting. It drew attention because it was different from surrounding lesions (FIGURE 2A), which has been called the “ugly duckling sign.”5 On closer examination, I noted the lesion had a pearly sheen, telangiectasias, and a plethora of dark dots (FIGURE 2B)—the poster child for the “dark dot sign.” Unlike this profound example, most lesions that have dark dots have just one or a few visible dots.

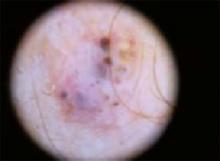

Now review FIGURE 1A again carefully. Above the lesion’s central crater there is an arcuate hemorrhagic crust, and, between the 12 and 1 o’clock positions, a small dark dot, which helps corroborate the clinical impression of BCC. FIGURE 1B is a dermoscopic image of the same lesion. It shows the dark dot well and illustrates the ease with which telangiectasias are seen on dermoscopy, lending a high degree of certainty to the diagnosis of BCC.

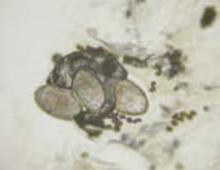

Dermoscopy (FIGURE 2C) for the lesion on the patient’s back in FIGURE 2B, however, adds nothing (beyond magnification) because telangiectasias and dark dots were visible clinically.

CASE #1

FIGURE 1A

Basal cell carcinoma. Even with photography, which is often clearer than magnified clinical inspection, telangiectasias are not well seen in this basal cell carcinoma. A dark dot, however, is visible between the 12 and 1 o’clock positions.

FIGURE 1B

A dermoscopic view of the BCC in FIGURE 1A clearly shows telangiectasias and a dark dot.

CASE #2

FIGURE 2A

Ugly duckling sign. The circled lesion on this patient’s back wasn’t crusty or bleeding, but it drew attention because it was different from surrounding lesions. This has been called the “ugly duckling sign.”

FIGURE 2B

Dark dots. A closer look at the lesion on the patient’s back revealed multiple dark dots and telangiectasias, virtually diagnostic of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 2C

A dermoscopic view of the lesion in FIGURE 2B adds little to what was well visualized clinically.

Caution: Context is critical

Because dots or blotches of pigment may occur in squamous cell carcinoma, pigmented actinic keratoses, seborrheic keratoses, and hypomelanotic or “amelanotic” melanoma, it is not possible clinically to confirm a diagnosis of BCC solely on the basis of dark dots. (In fact, even in the absence of pigment, any “red and white” lesion could be an amelanotic melanoma.) However, when added to other findings, such as a firm, pearly papule, the finding increases the likelihood of BCC.

How to proceed to biopsy

Lesions such as the ones I’ve shown should never be treated without preserving a specimen for pathology examination (eg, directly frozen). That said, there is no one right biopsy technique. The choice will depend on your clinical suspicion and perhaps other factors in your patient’s circumstance.

If you believe the lesion could be a cutaneous melanoma, the ideal option is full excision (to reduce sampling error pathologically), with a narrow margin (to preserve lymphatics, should sentinel node biopsy be considered later) and full thickness (to subcutaneous fat for prognostic staging; remember the dermis on the back is very thick). If you are confident the lesion is BCC, an initial shave biopsy preserves the option for treatment via curettage should the histology reveal superficial or nodular BCC. Pathology findings that indicate infiltrative, morpheaform, or micronodular BCC require excision; curettage is not adequate treatment for these lesions.

Treating the 2 patients

The patient in FIGURE 1A had no symptoms and no history of skin cancer. Because he was skeptical of the diagnosis, I performed a shave biopsy for histologic verification. The pathology report confirmed nodular BCC. We discussed options, and the patient elected excision.

In the case of the second lesion (FIGURE 2B), the diagnosis of BCC was fairly certain. Because of the patient’s advanced age, declining health, and difficulty arranging transportation, we decided to perform a primary excision at the outset. Had histology shown BCC with micronodular architecture or infitrative features, a shave biopsy for diagnosis, plus curettage, would not have been ideal treatment. Histology showed a nodular BCC.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center (Toledo) staff for its expert assistance.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 E 2nd Street, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Goldberg LH, Friedman RH, Silapunt S. Pigmented speckling as a sign of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1553-1555.

2. Bates B. A black dot appears to flag early basal cell carcinoma. Family Practice News. 2006;36(11):38.-Available at: http://www.familypracticenews.com/article/PIIS0300707306733047/fulltext. Accessed December 4, 2008.

3. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004:107-117, 157.

4. Polsky D. Non-melanocytic lesions: pigmented basal cell carcinoma [Chapter 6a]. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:55-59.

5. Grob JJ, Bonerandi JJ. The ‘ugly duckling’ sign: identification of the common characteristics of nevi in an individual as a basis for melanoma screening. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:103-104.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy, but it can still be a tricky and difficult diagnosis even in the most experienced hands. Many BCCs exhibit only some of the defining clinical characteristics, and even when these findings are present, they can be hard to detect without excellent background and oblique lighting and handheld magnification that is 5-power or greater.

Most clinicians are familiar with classic BCC characteristics of pearliness, rolled edges, telangiectasia, bleeding, and crusting. However, the telangiectasias may be so fine that they are difficult or impossible to see, even with excellent lighting and magnification. FIGURE 1A illustrates a histologically verified nodular BCC with telangiectasias that are not readily visible, even with camera macro magnification.

Some BCC papules or plaques lack the classic rolled edges, even when viewed with oblique lighting and magnification. Some lesions may be more scaly than pearly, and others do not bleed and crust until later in their clinical course. With such variation in clinical presentation, all possible clues to BCC are welcome.

Dark dots: Connecting them to BCC

One underappreciated sign that may help with the diagnosis of BCC is the “dark dot sign.”1,2 Dermoscopists are familiar with patterns of pigmentation associated with BCCs, and introductory dermoscopy texts contain pictures of these patterns (blue/blue-gray blotches, maple leaf structures, and spoke-wheel structures).3,4 What is less well known is that this pigmentation may be visible on routine skin examination as “dark dots”—blue, gray, black, or a combination thereof, such as blue-gray. When visible clinically, these dark dots may bolster one’s confidence in the diagnosis—or, in my experience, occasionally even be the best visible hint for a tentative diagnosis of BCC.

Case in point. During a routine skin examination of a patient’s back, I identified an asymptomatic lesion the patient was unaware of, exhibiting no bleeding or crusting. It drew attention because it was different from surrounding lesions (FIGURE 2A), which has been called the “ugly duckling sign.”5 On closer examination, I noted the lesion had a pearly sheen, telangiectasias, and a plethora of dark dots (FIGURE 2B)—the poster child for the “dark dot sign.” Unlike this profound example, most lesions that have dark dots have just one or a few visible dots.

Now review FIGURE 1A again carefully. Above the lesion’s central crater there is an arcuate hemorrhagic crust, and, between the 12 and 1 o’clock positions, a small dark dot, which helps corroborate the clinical impression of BCC. FIGURE 1B is a dermoscopic image of the same lesion. It shows the dark dot well and illustrates the ease with which telangiectasias are seen on dermoscopy, lending a high degree of certainty to the diagnosis of BCC.

Dermoscopy (FIGURE 2C) for the lesion on the patient’s back in FIGURE 2B, however, adds nothing (beyond magnification) because telangiectasias and dark dots were visible clinically.

CASE #1

FIGURE 1A

Basal cell carcinoma. Even with photography, which is often clearer than magnified clinical inspection, telangiectasias are not well seen in this basal cell carcinoma. A dark dot, however, is visible between the 12 and 1 o’clock positions.

FIGURE 1B

A dermoscopic view of the BCC in FIGURE 1A clearly shows telangiectasias and a dark dot.

CASE #2

FIGURE 2A

Ugly duckling sign. The circled lesion on this patient’s back wasn’t crusty or bleeding, but it drew attention because it was different from surrounding lesions. This has been called the “ugly duckling sign.”

FIGURE 2B

Dark dots. A closer look at the lesion on the patient’s back revealed multiple dark dots and telangiectasias, virtually diagnostic of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 2C

A dermoscopic view of the lesion in FIGURE 2B adds little to what was well visualized clinically.

Caution: Context is critical

Because dots or blotches of pigment may occur in squamous cell carcinoma, pigmented actinic keratoses, seborrheic keratoses, and hypomelanotic or “amelanotic” melanoma, it is not possible clinically to confirm a diagnosis of BCC solely on the basis of dark dots. (In fact, even in the absence of pigment, any “red and white” lesion could be an amelanotic melanoma.) However, when added to other findings, such as a firm, pearly papule, the finding increases the likelihood of BCC.

How to proceed to biopsy

Lesions such as the ones I’ve shown should never be treated without preserving a specimen for pathology examination (eg, directly frozen). That said, there is no one right biopsy technique. The choice will depend on your clinical suspicion and perhaps other factors in your patient’s circumstance.

If you believe the lesion could be a cutaneous melanoma, the ideal option is full excision (to reduce sampling error pathologically), with a narrow margin (to preserve lymphatics, should sentinel node biopsy be considered later) and full thickness (to subcutaneous fat for prognostic staging; remember the dermis on the back is very thick). If you are confident the lesion is BCC, an initial shave biopsy preserves the option for treatment via curettage should the histology reveal superficial or nodular BCC. Pathology findings that indicate infiltrative, morpheaform, or micronodular BCC require excision; curettage is not adequate treatment for these lesions.

Treating the 2 patients

The patient in FIGURE 1A had no symptoms and no history of skin cancer. Because he was skeptical of the diagnosis, I performed a shave biopsy for histologic verification. The pathology report confirmed nodular BCC. We discussed options, and the patient elected excision.

In the case of the second lesion (FIGURE 2B), the diagnosis of BCC was fairly certain. Because of the patient’s advanced age, declining health, and difficulty arranging transportation, we decided to perform a primary excision at the outset. Had histology shown BCC with micronodular architecture or infitrative features, a shave biopsy for diagnosis, plus curettage, would not have been ideal treatment. Histology showed a nodular BCC.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center (Toledo) staff for its expert assistance.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 E 2nd Street, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy, but it can still be a tricky and difficult diagnosis even in the most experienced hands. Many BCCs exhibit only some of the defining clinical characteristics, and even when these findings are present, they can be hard to detect without excellent background and oblique lighting and handheld magnification that is 5-power or greater.

Most clinicians are familiar with classic BCC characteristics of pearliness, rolled edges, telangiectasia, bleeding, and crusting. However, the telangiectasias may be so fine that they are difficult or impossible to see, even with excellent lighting and magnification. FIGURE 1A illustrates a histologically verified nodular BCC with telangiectasias that are not readily visible, even with camera macro magnification.

Some BCC papules or plaques lack the classic rolled edges, even when viewed with oblique lighting and magnification. Some lesions may be more scaly than pearly, and others do not bleed and crust until later in their clinical course. With such variation in clinical presentation, all possible clues to BCC are welcome.

Dark dots: Connecting them to BCC

One underappreciated sign that may help with the diagnosis of BCC is the “dark dot sign.”1,2 Dermoscopists are familiar with patterns of pigmentation associated with BCCs, and introductory dermoscopy texts contain pictures of these patterns (blue/blue-gray blotches, maple leaf structures, and spoke-wheel structures).3,4 What is less well known is that this pigmentation may be visible on routine skin examination as “dark dots”—blue, gray, black, or a combination thereof, such as blue-gray. When visible clinically, these dark dots may bolster one’s confidence in the diagnosis—or, in my experience, occasionally even be the best visible hint for a tentative diagnosis of BCC.

Case in point. During a routine skin examination of a patient’s back, I identified an asymptomatic lesion the patient was unaware of, exhibiting no bleeding or crusting. It drew attention because it was different from surrounding lesions (FIGURE 2A), which has been called the “ugly duckling sign.”5 On closer examination, I noted the lesion had a pearly sheen, telangiectasias, and a plethora of dark dots (FIGURE 2B)—the poster child for the “dark dot sign.” Unlike this profound example, most lesions that have dark dots have just one or a few visible dots.

Now review FIGURE 1A again carefully. Above the lesion’s central crater there is an arcuate hemorrhagic crust, and, between the 12 and 1 o’clock positions, a small dark dot, which helps corroborate the clinical impression of BCC. FIGURE 1B is a dermoscopic image of the same lesion. It shows the dark dot well and illustrates the ease with which telangiectasias are seen on dermoscopy, lending a high degree of certainty to the diagnosis of BCC.

Dermoscopy (FIGURE 2C) for the lesion on the patient’s back in FIGURE 2B, however, adds nothing (beyond magnification) because telangiectasias and dark dots were visible clinically.

CASE #1

FIGURE 1A

Basal cell carcinoma. Even with photography, which is often clearer than magnified clinical inspection, telangiectasias are not well seen in this basal cell carcinoma. A dark dot, however, is visible between the 12 and 1 o’clock positions.

FIGURE 1B

A dermoscopic view of the BCC in FIGURE 1A clearly shows telangiectasias and a dark dot.

CASE #2

FIGURE 2A

Ugly duckling sign. The circled lesion on this patient’s back wasn’t crusty or bleeding, but it drew attention because it was different from surrounding lesions. This has been called the “ugly duckling sign.”

FIGURE 2B

Dark dots. A closer look at the lesion on the patient’s back revealed multiple dark dots and telangiectasias, virtually diagnostic of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 2C

A dermoscopic view of the lesion in FIGURE 2B adds little to what was well visualized clinically.

Caution: Context is critical

Because dots or blotches of pigment may occur in squamous cell carcinoma, pigmented actinic keratoses, seborrheic keratoses, and hypomelanotic or “amelanotic” melanoma, it is not possible clinically to confirm a diagnosis of BCC solely on the basis of dark dots. (In fact, even in the absence of pigment, any “red and white” lesion could be an amelanotic melanoma.) However, when added to other findings, such as a firm, pearly papule, the finding increases the likelihood of BCC.

How to proceed to biopsy

Lesions such as the ones I’ve shown should never be treated without preserving a specimen for pathology examination (eg, directly frozen). That said, there is no one right biopsy technique. The choice will depend on your clinical suspicion and perhaps other factors in your patient’s circumstance.

If you believe the lesion could be a cutaneous melanoma, the ideal option is full excision (to reduce sampling error pathologically), with a narrow margin (to preserve lymphatics, should sentinel node biopsy be considered later) and full thickness (to subcutaneous fat for prognostic staging; remember the dermis on the back is very thick). If you are confident the lesion is BCC, an initial shave biopsy preserves the option for treatment via curettage should the histology reveal superficial or nodular BCC. Pathology findings that indicate infiltrative, morpheaform, or micronodular BCC require excision; curettage is not adequate treatment for these lesions.

Treating the 2 patients

The patient in FIGURE 1A had no symptoms and no history of skin cancer. Because he was skeptical of the diagnosis, I performed a shave biopsy for histologic verification. The pathology report confirmed nodular BCC. We discussed options, and the patient elected excision.

In the case of the second lesion (FIGURE 2B), the diagnosis of BCC was fairly certain. Because of the patient’s advanced age, declining health, and difficulty arranging transportation, we decided to perform a primary excision at the outset. Had histology shown BCC with micronodular architecture or infitrative features, a shave biopsy for diagnosis, plus curettage, would not have been ideal treatment. Histology showed a nodular BCC.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center (Toledo) staff for its expert assistance.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 E 2nd Street, Defiance, OH 43512; foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Goldberg LH, Friedman RH, Silapunt S. Pigmented speckling as a sign of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1553-1555.

2. Bates B. A black dot appears to flag early basal cell carcinoma. Family Practice News. 2006;36(11):38.-Available at: http://www.familypracticenews.com/article/PIIS0300707306733047/fulltext. Accessed December 4, 2008.

3. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004:107-117, 157.

4. Polsky D. Non-melanocytic lesions: pigmented basal cell carcinoma [Chapter 6a]. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:55-59.

5. Grob JJ, Bonerandi JJ. The ‘ugly duckling’ sign: identification of the common characteristics of nevi in an individual as a basis for melanoma screening. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:103-104.

1. Goldberg LH, Friedman RH, Silapunt S. Pigmented speckling as a sign of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1553-1555.

2. Bates B. A black dot appears to flag early basal cell carcinoma. Family Practice News. 2006;36(11):38.-Available at: http://www.familypracticenews.com/article/PIIS0300707306733047/fulltext. Accessed December 4, 2008.

3. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004:107-117, 157.

4. Polsky D. Non-melanocytic lesions: pigmented basal cell carcinoma [Chapter 6a]. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:55-59.

5. Grob JJ, Bonerandi JJ. The ‘ugly duckling’ sign: identification of the common characteristics of nevi in an individual as a basis for melanoma screening. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:103-104.

10 derm mistakes you don’t want to make

I’ve seen my share of missed diagnoses over the years while caring for patients who, through physician- or self-referral, have made their way to our multi-specialty group practice where I focus solely on skin.

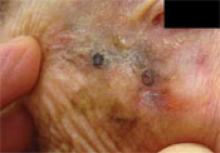

There was the 93-year-old patient whose “sun spot” had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists in the past and turned out to be a lentigo maligna melanoma (FIGURE 1).

There was the patient who had a lesion on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years” that neither caught the attention of her physician, nor her dentist (FIGURE 2). Histology showed she had an infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

And then there was the wife of a healthcare professional who decided she wanted a “second opinion” for the asymptomatic lesion on her leg that her husband assured her was benign. Her diagnosis was not so simple: She had a MELanocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP) that required careful follow-up (FIGURE 3).

Early detection, as we all know, is the name of the game when it comes to skin malignancies. Yet every day, opportunities to catch small, early lesions are missed.

During the past couple of years, I’ve had thousands of patient visits for skin problems and diagnosed more than 1000 skin malignancies. The majority of patients have had some treatment for their presenting dermatosis prior to arrival. Based on my experiences with these patients, I’ve developed a list of common dermatology “mistakes.” Here they are, with some tips for avoiding them.

FIGURE 1

Melanoma missed by 2 dermatologists

This “sun spot” was of no concern to the 93-year-old patient because she had been evaluated and treated by 2 different dermatologists. The darkest areas are dermoscopically-directed pen markings for incisional biopsy. (The size of the lesion and proximity to the eye precluded primary excisional biopsy.) This “sun spot” turned out to be lentigo maligna melanoma.

FIGURE 2

Lesion on lip for “10—maybe 20—years”

This patient had a lesion that had been on her lip for “at least 10—maybe 20—years.” The patient said it had never bled or crusted. Telangiectasia, pearliness, and some infiltration were present. Histologic diagnosis: infiltrative basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3

A case of MELTUMP

Two dermatopathologists read the biopsy as Spitzoid malignant melanoma, Clark Level III, and Breslow thickness 0.9 mm. Two independent dermatopathologists read the same original slides in consultation as atypical Spitz nevus. The 4 could not reach agreement. Final clinical diagnosis: MEL anocytic Tumor of Unknown Malignant Potential (MELTUMP).

Mistake #1: Not looking (and not biopsying)

I had a woman come into the office to have a lesion assessed. She had seen a dermatologist a couple of weeks earlier and even had a number of lesions removed during that visit. The patient told me that she’d repeatedly tried to show the dermatologist one specific lesion—the one of greatest concern to her—just below her underpants line, but the physician was in and out so fast each time, she never had the chance to point out this one melanocytic, changing lesion.

The lesion turned out to be a dysplastic nevus with severe architectural and cytologic atypia. This type of lesion requires histology to differentiate it from melanoma, and could just as easily have been a melanoma.

Almost daily I treat patients who are being seen by their primary care physicians regularly, and have obvious basal cell carcinomas (BCC) or squamous cell carcinomas. I have even found skin malignancies on physicians, their spouses, and their family members.1 These lesions can be easily missed—if you don’t look carefully.

Consider, the following:

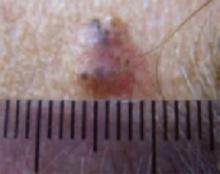

- FIGURE 4 illustrates a superficial BCC on the forearm of a physician who was totally unaware of it. (It was detected on “routine” skin examination.)

- FIGURE 5 illustrates a BCC on a patient’s central forehead that, by her history, had been there for many years, and was not of any concern to her. The patient was referred to our office for evaluation of itchy skin on her legs.

- FIGURE 2 illustrates a lesion that, according to the patient, had been on her lip for at least 10—and perhaps even 20—years and was of no concern to her. (It was not the reason for the visit.) Over the years, this patient certainly had numerous primary care and dental visits, but no one “saw” the lesion. Histology confirmed the clinical impression of BCC.

FIGURE 4

Superficial BCC on physician’s forearm

A physician asked for a skin examination, but was totally unaware of this asymptomatic lesion on his dorsal forearm. Once it was identified, he could provide no history about its duration. The lesion had never bled or crusted. Pathology confirmed that it was a superficial basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 5

“Mole” on forehead for many years

This patient was referred for itchy legs. She was unconcerned about a prominent “mole” noted on examination of her forehead, one that she said had been there, unchanged, for many years. Histology confirmed nodular basal cell carcinoma.

- Look, look, and look again, especially at sun-exposed areas (faces, ears, scalps [as hair thins], and dorsal forearms).

- Make sure patients are appropriately gowned no matter what the reason for their visit. Listening to heart and lung sounds and palpating abdomens through overcoats may work for some physicians, but not those interested in finding asymptomatic basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. Melanoma in men is most common on the back; in women, it’s most common on the legs. Seeing these areas requires that they be accessible.

- Biopsy when you’re in doubt. If you see a lesion and it is not recognizable as benign (eg, cherry angioma, seborrheic keratosis, nevus), biopsy it. Let the pathologist determine if it’s benign or malignant. If the lesion is questionable and is in an area that you are uncomfortable biopsying, refer the patient for evaluation and potential biopsy.

Mistake #2: Using insufficient light

As a former family practice academic, I used to preach to residents that they needed to use “light, light, and more light” for evaluation of skin lesions. Despite this, I was often asked to evaluate a patient with a resident who hadn’t even bothered to turn on a goose-neck lamp for illumination.

Even with my current “double bank” daylight fluorescent examination room lighting, it often takes additional (surgical-type) lighting to see the diagnostic features of skin lesions. Without such intense light, it is often impossible to see whether there is pearliness, rolled edges, or fine telangiectasia.

- Use whatever intense source of light you have, whether it’s a goose-neck lamp, a halogen, or a surgical light. If you don’t have at least a portable source of bright light, you are under-equipped for a good skin exam.

Mistake #3: Using insufficient (or no) magnification

I was once examining a patient in a hospital room that had inadequate light, despite my best efforts. So I took out my digital camera with flash and autofocus feature and photographed the lesion. I then looked at the lesion on the camera’s LCD monitor and determined that it was a BCC.

The benefit of the camera was 2-fold: Not only did the flash serve as an instant source of light, but the macro feature also provided magnification. Viewing a magnified digital image on a computer screen also allows unhurried, self “second opinions,” where details can often be ascertained that were not immediately apparent in “real time,” such as rolled edges, telangiectasia, dots, streaks, and subtleties of color.

- Use a hand-held magnifying lens (5X to 10X) routinely during skin exams. They’re not expensive and should be part of every primary care physician’s armamentarium—just like stethoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and reflex hammers.

- Use a digital camera to provide the magnification needed to see details that can be missed clinically. I’m convinced that using a digital camera has made me a better observer—and clinician. Additionally, digital photographs can be stored and compared with histologic results as “self-education.” When purchasing a camera for this purpose, make sure it has a good close-up (macro) feature.

Mistake #4: Assuming that pathology is a perfect science

Most physicians assume that dermatopathologists have a high rate of interrater concordance with diagnoses such as melanoma. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Consider the following:

- As part of a National Institutes of Health consensus conference on melanoma, 8 dermatopathologists considered experts in melanoma were asked to provide 5 slides each. The slides were relabeled and sent to the same 8 dermatopathologists. (Three slides were eliminated.) Their findings: At the extremes, 1 pathologist called 21 cases melanoma and 16 benign, whereas another called 10 melanoma, 26 benign, and one indeterminate.2 (Remember: These were all experts in melanoma.)

- In a study of 30 melanocytic lesion specimens (including Spitzoid lesions), 10 Harvard dermatopathologists evaluated each sample independently of each other. Given 5 diagnostic categories to choose from, in only one case did as many as 6 of the 10 agree on a diagnosis. In all of these cases, there was long-term clinical follow-up, so the biologic behavior of these lesions was known. Some lesions that proved fatal were categorized by most observers as benign (eg, Spitz nevi or atypical Spitz tumors). The converse, reporting benign lesions as melanoma, also occurred.3

So consider this: If this degree of discordance occurs among dermatopathologists, what results could we expect from non-dermatopathologists?

I have personally seen instances where reports of melanoma from non-dermatopathologists did not even report Clark and Breslow staging information (although one could determine Clark staging from reading the body of the report), and reports of dysplastic nevi that were accompanied by recommendations for re-excision with 1 cm margins.

When I have a report from a general pathologist suggesting a potentially worrisome lesion (melanoma, severely dysplastic nevus, [atypical] Spitz nevus), I always suggest to my patients that we get a dermatopathologic second opinion. (I send all my dermatopathology specimens to dermatopathologists, so this applies to patients referred in with prior pathology in hand.)

Sometimes, even the dermatopathologists do not agree on the nature of the lesion. In such cases, I have my “MELTUMP discussion” with patients. That is, I tell patients that we don’t know for sure what it is, and that ultimately only the final lab test—time—will tell us the true nature of the lesion (FIGURE 3).4

- Send all “skin” to a dermatopathologist. You owe it to your patients.

- Send pictures (electronic or hard copy) to the dermatopathologist when the pathology report and clinical picture do not appear to match. While pictures of skin lesions and dermoscopic photographs would most likely be meaningless to general pathologists, they are useful to dermatopathologists. Research has shown that pathologists in various areas of medicine may alter their diagnosis or differential diagnosis when presented with additional clinical information.5

Mistake #5: Freezing neoplasms without a definitive Dx

“We’ll freeze it and if it doesn’t go away, then…”

This approach poses a significant risk to you (medicolegally) and your patient.

While most of the time what I see has been inappropriately frozen first by first-line providers, that is not always the case. Dermatologists also fall into this trap. FIGURE 6 shows a lesion just behind the hairline on the frontoparietal scalp that was frozen by a very good, and reputable, dermatologist. The patient came to me for a second opinion with an “obvious” BCC.

Some clinicians are “thrown off” when a lesion (like the one on this patient) has hair. Some sources6 indicate that BCCs never have hair, but this is patently untrue.

FIGURE 6

This shouldn’t have been frozen

A dermatologist froze this lesion on a patient’s scalp, believing that it was seborrheic keratosis, based on the patient’s history. The patient sought a second opinion, and the lesion (which had hair) was histologically identified as basal cell carcinoma.

- Don’t freeze a lesion when you are unsure; biopsy it. This is especially critical when you consider that cryotherapy is not considered a first-line treatment for BCC, the most common human malignancy. It is better to biopsy, assure the diagnosis, and then provide the appropriate therapy.

Mistake #6: Treating psoriasis with systemic corticosteroids

Plaque psoriasis can, albeit uncommonly, be transformed to pustular psoriasis after the administration of oral or injectable systemic corticosteroids.7 Although this rarely occurs, most experts consider this poor practice and not worth the risk. In addition, some experts note that systemic glucocorticoids are a drug trigger for inducing or exacerbating psoriasis.8

- Avoid systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis, since psoriasis is generally a long-term disease and systemic corticosteroids are a short-term fix. if there is widespread psoriasis and you are not familiar with systemic treatments, refer the patient. If there is localized disease, consider topical treatment options—such as various strengths of corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tazarotene (individually or in combination)—depending on location and plaque thickness.

Mistake #7: Doing shave biopsies on melanocytic lesions

For a melanoma, not only can shaving part way through the vertical dimension of the lesion interfere with staging, it can also hinder the pathologist’s ability to arrive at the correct diagnosis.9

- Do a full-thickness, narrow-margin, fully excisional biopsy when you suspect melanoma. Certainly, there are individuals who are expert at saucerization (deep shave biopsies, often with scalloped, sloping edges that go to the deep reticular dermis) and who can perform biopsies of melanocytic lesions while still obtaining reasonable pathologic staging information.

Mistake #8: Using corticosteroid/antifungal combination products