User login

Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis and Palisaded Neutrophilic Granulomatous Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

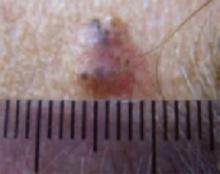

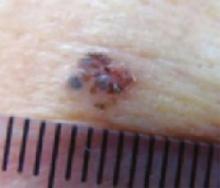

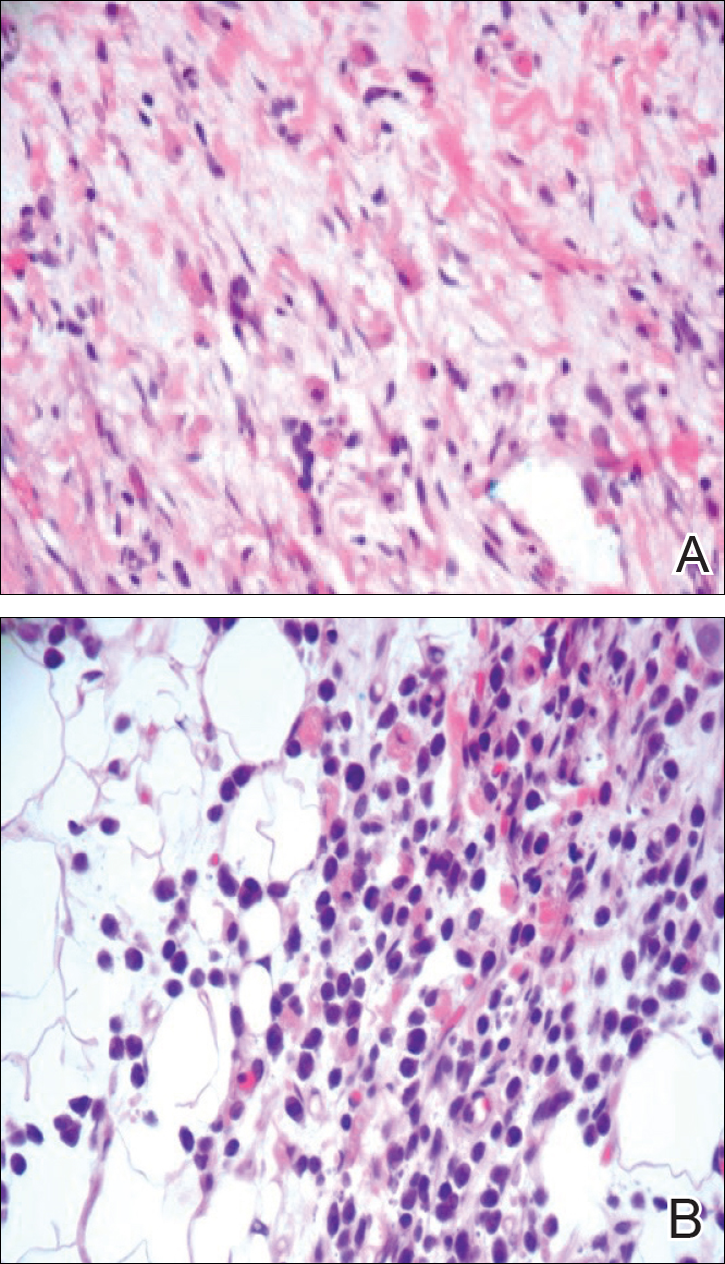

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

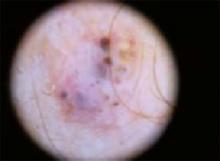

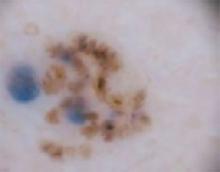

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

Practice Points

- The clinical features of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis exist on a spectrum, and these is considerable overlap between the features of these 2 clinicopathologic entities.

- Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis may respond to systemic steroids or treatment of the underlying systemic disease. Some cases spontaneously resolve.

Blueberry Muffin Rash Secondary to Hereditary Spherocytosis

The term blueberry muffin rash historically was used to describe the cutaneous manifestations observed in congenital rubella. The term traditionally describes the result of a postnatal dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis. Today, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) infections and plasma cell dyscrasias are all potential causes of extramedullary hematopoiesis. Herein, we present a unique case of a neonate born with a blueberry muffin rash secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis induced by hereditary spherocytosis.

Case Report

The dermatology department was consulted to evaluate a 2-day-old male neonate born with a “rash.” The patient was born to a 34-year-old gravida 3, para 2, woman at 39 weeks’ gestation. The mother’s prenatal laboratory values were within reference range and ultrasounds were normal, and she was compliant with her prenatal care. She underwent a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery 3 hours after rupture of membranes without complication. The amniotic fluid and umbilical cord both were clear. There was no use of forceps or any other external aiding devices during the delivery. At the time of delivery, the consulting physician noted that the patient had “skin lesions from head to toe.”

The patient’s parents reported that the rash did not seem to cause any discomfort for the patient. In the 24 hours after birth, the parents reported that the erythema seemed to slightly fade. Physical examination revealed many scattered erythematous to violaceous, nonblanching papulonodules affecting the scalp (Figure 1), face, arms, hands (Figure 2A), back (Figure 2B), buttocks, legs, and feet. Some of the papulonodules were soft while others were firm and indurated. Several lesions had a yellowish hue with some overlying crust. There was no mucosal, genital, or ocular involvement. No erosions, ulcerations, petechiae, ecchymoses, or hepatosplenomegaly were noted on examination.

The patient was otherwise healthy with an Apgar score of 8/9 at 1 and 5 minutes. His birth weight, length, and head circumference were within normal limits. There was no evidence of ABO blood group or Rhesus factor incompatibility. His temperature, vital signs, laboratory values (including calcium level and TORCH titers, which included cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis, and herpes simplex virus), and review of systems all were within reference range. A bone survey of the skull, spine, ribs, arms, pelvis, legs, and feet was within normal limits.

The mother’s placenta was sent for pathology and revealed a lymphoplasmacytic chronic deciduitis and acute subchorionitis consistent with a nonspecific inflammatory response, unlikely to be from an infectious etiology.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the left thigh and revealed a predominately lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils and erythrocyte precursors (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining was performed showing that the majority of the lymphocytes represented T lymphocytes, which stained positive for CD45 and CD3 and negative for S-100, CD1a, CD30, and CD117. There were scattered CD34+ cells, and scattered cells stained positive for myeloperoxidase. No significant CD20 immunoreactivity was noted. There were scattered eosinophils and rare normoblasts but no megakaryocytes. A complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential and reticulocyte count was within reference range.

At 1-, 3-, 8-, 12-, and 28-week follow-up visits, the patient continued to grow and feed appropriately. No new lesions developed during this time, and the preexisting lesions continued to fade into slightly hyperpigmented patches without induration (Figure 4). At 6 months of age, a CBC performed at the time of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), a reticulocyte count of 0.8% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%), and a lactate dehydrogenase level of 424 U/L (reference range, 100–200 U/L). All red blood cell (RBC) indices were within reference range. Flow cytometry, eosin-5-maleimide, and ektacytometry were performed with results consistent with mild hereditary spherocytosis.

Comment

Dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis is a normal component of embryologic development up until the fifth month of gestation.1 The term blueberry muffin rash typically is used to describe the cutaneous manifestations of extramedullary hematopoiesis, which commonly is caused by a TORCH infection or hematologic dyscrasia.2 It has been suggested that the term be expanded to include neoplastic processes (eg, neuroblastomas) and vascular processes (eg, multiple hemangiomas, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, glomangiomas, multifocal lymphangionendotheliomatosis), which although not associated with an extramedullary hematopoiesis, can clinically resemble a blueberry muffin rash.

Because of the potential for serious systemic complications, a cause must be sought for all newborns presenting with a blueberry muffin rash. Our patient’s lack of cardiovascular, otic, and ocular involvement combined with a negative TORCH screen and normal CBC strongly suggested against a TORCH infection. In addition, a normal bone survey and CBC, as well as a lack of petechiae, ecchymoses, and hepatosplenomegaly, were evidence against congenital leukemia.3 With the spontaneously resolving lesions and apparent clinical resolution, a bone marrow biopsy was not performed. The skin biopsy revealed negative staining for S-100 and CD1a, making the diagnosis of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis unlikely. No panniculitis was noted and calcium levels were normal, ruling out subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. The predominantly T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate demonstrated on skin biopsy led us to a differential diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis versus idiopathic dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis; however, normocytic anemia was later identified when the patient’s hemoglobin level dropped to 9.9 g/dL. The abnormal eosin-5-maleimide and ektacytometry results unmasked a hereditary spherocytosis.

Hereditary spherocytosis typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and may be caused by mutations in ankyrin-1, band 3, spectrin, or protein 4.2 on the erythrocyte membrane. It is the third leading cause of hemolytic anemia in newborns and the leading cause of direct Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion in neonates. It is most common in neonates of Northern European ancestry, affecting 1 in every 1000 to 2000 births.4 Presentation may range from asymptomatic to severe anemia with hydrops fetalis. Most neonates have an elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin and low mean corpuscular volume. Acute illness may cause hemolytic or aplastic crises, possibly explaining our patient’s normocytic anemia discovered on a CBC during an episode of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media.

Treatment options for hereditary spherocytosis include phototherapy for jaundiced neonates, folate supplementation, packed erythrocyte transfusions for symptomatic anemia, and recombinant erythropoietin in neonates.4 Splenectomy is curative for the majority of patients and requires immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis several weeks preoperatively. Patients with symptomatic gallstones may be treated with cholecystectomy at the time of splenectomy or by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy, cholecystostomy, or extracorporeal cholecystolithotripsy.5

Although a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms dermal hematopoiesis, extramedullary hematopoiesis, hereditary spherocytosis, and blueberry muffin rash yielded only 1 other known case of blueberry muffin rash caused by hereditary spherocytosis,6 other case reports demonstrate extramedullary hematopoiesis in hereditary spherocytosis patients in locations other than the skin. Calhoun et al7 described a case of a 9-year-old boy with hereditary spherocytosis who presented with jaundice. Pathologic examination revealed a 5-cm suprarenal mass demonstrating extramedullary hematopoiesis.7 A case reported by Xiros et al8 described a 64-year-old man with a history of hereditary spherocytosis who presented with hemothorax from paravertebral extramedullary hematopoiesis. De Backer et al9 reported a case of a 60-year-old man diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis after an abnormal CBC who was subsequently found to have paravertebral masses containing extramedullary hematopoiesis.

There is one known case of a blueberry muffin rash caused by hereditary spherocytosis.6 A female neonate was born at 38 weeks’ gestation with multiple petechiae and faint purpuric papules. Initial complications included intracranial ventricular hemorrhage, hyperbilirubinemia, and anemia requiring blood transfusions on the first day of life. TORCH titers were negative and a skin biopsy demonstrated a diffuse infiltrate of mature RBCs, normoblasts, and pronormoblasts in the reticular dermis. She was healthy until 3 months of age when she had several days of vomiting and diarrhea. Laboratory workup revealed a hematocrit level of 20.5% (reference range, 41%–50%); a reticulocyte count of 22.6% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%); and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating polychromatophilia, anisocytosis, and spherocytosis. She was then diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis.6

Hereditary spherocytosis is a known, albeit rare, cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis presenting as blueberry muffin rash. Patients with mild hereditary spherocytosis may have a compensated hemolysis without anemia or spherocytes on peripheral smear, which may explain the lack of severe hemolytic anemia or RBC-predominant pathology in our patient.5 Argyle and Zone6 proposed that severe hemolysis and hypoxia were the cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis in their patient. Because our patient did not experience a notable hemolytic episode until he had an upper respiratory infection and otitis media at 6 months of age, the pathophysiology is less clear; a compensated hemolytic process may underlie the extramedullary hematopoiesis and normal RBC indices.

Regardless of the precise cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis in our patient, this case of a T lymphocyte–dominant cutaneous infiltrate in a patient with mild hereditary spherocytosis is exceptionally rare and leads us to consider that perhaps there are causes of this pathology that are unknown to us.

- Zhang IH, Zane LT, Braun BS, et al. Congenital leukemia cutis with subsequent development of leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S22–S27.

- Karmegaraj B, Vijayakumar S, Ramanathan R, et al. Extramedullary haematopoiesis resembling a blueberry muffin, in a neonate. BMJ Case Rep. pii: bcr2014208473. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-208473.

- Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Neonatal leukaemia cutis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1884-1889.

- Christensen RD, Yaish HM, Gallagher PG. A pediatrician’s practical guide to diagnosing and treating hereditary spherocytosis in neonates. Pediatrics. 2015;135:1107-1114.

- Perrotta S, Gallagher PG, Mohandas N. Hereditary spherocytosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1411-1426.

- Argyle JC, Zone JJ. Dermal erythropoiesis in a neonate. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:492-494.

- Calhoun SK, Murphy RC, Shariati N, et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis in a child with hereditary spherocytosis: an uncommon cause of an adrenal mass. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:879-881.

- Xiros N, Economopoulos T, Papageorgiou E, et al. Massive hemothorax due to intrathoracic extramedullary hematopoiesis in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:38-40.

- De Backer AI, Zachée P, Vanschoubroeck IJ, et al. Extramedullary paraspinal hematopoiesis in hereditary spherocytosis. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:206-208.

The term blueberry muffin rash historically was used to describe the cutaneous manifestations observed in congenital rubella. The term traditionally describes the result of a postnatal dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis. Today, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) infections and plasma cell dyscrasias are all potential causes of extramedullary hematopoiesis. Herein, we present a unique case of a neonate born with a blueberry muffin rash secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis induced by hereditary spherocytosis.

Case Report

The dermatology department was consulted to evaluate a 2-day-old male neonate born with a “rash.” The patient was born to a 34-year-old gravida 3, para 2, woman at 39 weeks’ gestation. The mother’s prenatal laboratory values were within reference range and ultrasounds were normal, and she was compliant with her prenatal care. She underwent a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery 3 hours after rupture of membranes without complication. The amniotic fluid and umbilical cord both were clear. There was no use of forceps or any other external aiding devices during the delivery. At the time of delivery, the consulting physician noted that the patient had “skin lesions from head to toe.”

The patient’s parents reported that the rash did not seem to cause any discomfort for the patient. In the 24 hours after birth, the parents reported that the erythema seemed to slightly fade. Physical examination revealed many scattered erythematous to violaceous, nonblanching papulonodules affecting the scalp (Figure 1), face, arms, hands (Figure 2A), back (Figure 2B), buttocks, legs, and feet. Some of the papulonodules were soft while others were firm and indurated. Several lesions had a yellowish hue with some overlying crust. There was no mucosal, genital, or ocular involvement. No erosions, ulcerations, petechiae, ecchymoses, or hepatosplenomegaly were noted on examination.

The patient was otherwise healthy with an Apgar score of 8/9 at 1 and 5 minutes. His birth weight, length, and head circumference were within normal limits. There was no evidence of ABO blood group or Rhesus factor incompatibility. His temperature, vital signs, laboratory values (including calcium level and TORCH titers, which included cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis, and herpes simplex virus), and review of systems all were within reference range. A bone survey of the skull, spine, ribs, arms, pelvis, legs, and feet was within normal limits.

The mother’s placenta was sent for pathology and revealed a lymphoplasmacytic chronic deciduitis and acute subchorionitis consistent with a nonspecific inflammatory response, unlikely to be from an infectious etiology.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the left thigh and revealed a predominately lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils and erythrocyte precursors (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining was performed showing that the majority of the lymphocytes represented T lymphocytes, which stained positive for CD45 and CD3 and negative for S-100, CD1a, CD30, and CD117. There were scattered CD34+ cells, and scattered cells stained positive for myeloperoxidase. No significant CD20 immunoreactivity was noted. There were scattered eosinophils and rare normoblasts but no megakaryocytes. A complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential and reticulocyte count was within reference range.

At 1-, 3-, 8-, 12-, and 28-week follow-up visits, the patient continued to grow and feed appropriately. No new lesions developed during this time, and the preexisting lesions continued to fade into slightly hyperpigmented patches without induration (Figure 4). At 6 months of age, a CBC performed at the time of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), a reticulocyte count of 0.8% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%), and a lactate dehydrogenase level of 424 U/L (reference range, 100–200 U/L). All red blood cell (RBC) indices were within reference range. Flow cytometry, eosin-5-maleimide, and ektacytometry were performed with results consistent with mild hereditary spherocytosis.

Comment

Dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis is a normal component of embryologic development up until the fifth month of gestation.1 The term blueberry muffin rash typically is used to describe the cutaneous manifestations of extramedullary hematopoiesis, which commonly is caused by a TORCH infection or hematologic dyscrasia.2 It has been suggested that the term be expanded to include neoplastic processes (eg, neuroblastomas) and vascular processes (eg, multiple hemangiomas, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, glomangiomas, multifocal lymphangionendotheliomatosis), which although not associated with an extramedullary hematopoiesis, can clinically resemble a blueberry muffin rash.

Because of the potential for serious systemic complications, a cause must be sought for all newborns presenting with a blueberry muffin rash. Our patient’s lack of cardiovascular, otic, and ocular involvement combined with a negative TORCH screen and normal CBC strongly suggested against a TORCH infection. In addition, a normal bone survey and CBC, as well as a lack of petechiae, ecchymoses, and hepatosplenomegaly, were evidence against congenital leukemia.3 With the spontaneously resolving lesions and apparent clinical resolution, a bone marrow biopsy was not performed. The skin biopsy revealed negative staining for S-100 and CD1a, making the diagnosis of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis unlikely. No panniculitis was noted and calcium levels were normal, ruling out subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. The predominantly T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate demonstrated on skin biopsy led us to a differential diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis versus idiopathic dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis; however, normocytic anemia was later identified when the patient’s hemoglobin level dropped to 9.9 g/dL. The abnormal eosin-5-maleimide and ektacytometry results unmasked a hereditary spherocytosis.

Hereditary spherocytosis typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and may be caused by mutations in ankyrin-1, band 3, spectrin, or protein 4.2 on the erythrocyte membrane. It is the third leading cause of hemolytic anemia in newborns and the leading cause of direct Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion in neonates. It is most common in neonates of Northern European ancestry, affecting 1 in every 1000 to 2000 births.4 Presentation may range from asymptomatic to severe anemia with hydrops fetalis. Most neonates have an elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin and low mean corpuscular volume. Acute illness may cause hemolytic or aplastic crises, possibly explaining our patient’s normocytic anemia discovered on a CBC during an episode of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media.

Treatment options for hereditary spherocytosis include phototherapy for jaundiced neonates, folate supplementation, packed erythrocyte transfusions for symptomatic anemia, and recombinant erythropoietin in neonates.4 Splenectomy is curative for the majority of patients and requires immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis several weeks preoperatively. Patients with symptomatic gallstones may be treated with cholecystectomy at the time of splenectomy or by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy, cholecystostomy, or extracorporeal cholecystolithotripsy.5

Although a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms dermal hematopoiesis, extramedullary hematopoiesis, hereditary spherocytosis, and blueberry muffin rash yielded only 1 other known case of blueberry muffin rash caused by hereditary spherocytosis,6 other case reports demonstrate extramedullary hematopoiesis in hereditary spherocytosis patients in locations other than the skin. Calhoun et al7 described a case of a 9-year-old boy with hereditary spherocytosis who presented with jaundice. Pathologic examination revealed a 5-cm suprarenal mass demonstrating extramedullary hematopoiesis.7 A case reported by Xiros et al8 described a 64-year-old man with a history of hereditary spherocytosis who presented with hemothorax from paravertebral extramedullary hematopoiesis. De Backer et al9 reported a case of a 60-year-old man diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis after an abnormal CBC who was subsequently found to have paravertebral masses containing extramedullary hematopoiesis.

There is one known case of a blueberry muffin rash caused by hereditary spherocytosis.6 A female neonate was born at 38 weeks’ gestation with multiple petechiae and faint purpuric papules. Initial complications included intracranial ventricular hemorrhage, hyperbilirubinemia, and anemia requiring blood transfusions on the first day of life. TORCH titers were negative and a skin biopsy demonstrated a diffuse infiltrate of mature RBCs, normoblasts, and pronormoblasts in the reticular dermis. She was healthy until 3 months of age when she had several days of vomiting and diarrhea. Laboratory workup revealed a hematocrit level of 20.5% (reference range, 41%–50%); a reticulocyte count of 22.6% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%); and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating polychromatophilia, anisocytosis, and spherocytosis. She was then diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis.6

Hereditary spherocytosis is a known, albeit rare, cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis presenting as blueberry muffin rash. Patients with mild hereditary spherocytosis may have a compensated hemolysis without anemia or spherocytes on peripheral smear, which may explain the lack of severe hemolytic anemia or RBC-predominant pathology in our patient.5 Argyle and Zone6 proposed that severe hemolysis and hypoxia were the cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis in their patient. Because our patient did not experience a notable hemolytic episode until he had an upper respiratory infection and otitis media at 6 months of age, the pathophysiology is less clear; a compensated hemolytic process may underlie the extramedullary hematopoiesis and normal RBC indices.

Regardless of the precise cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis in our patient, this case of a T lymphocyte–dominant cutaneous infiltrate in a patient with mild hereditary spherocytosis is exceptionally rare and leads us to consider that perhaps there are causes of this pathology that are unknown to us.

The term blueberry muffin rash historically was used to describe the cutaneous manifestations observed in congenital rubella. The term traditionally describes the result of a postnatal dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis. Today, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) infections and plasma cell dyscrasias are all potential causes of extramedullary hematopoiesis. Herein, we present a unique case of a neonate born with a blueberry muffin rash secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis induced by hereditary spherocytosis.

Case Report

The dermatology department was consulted to evaluate a 2-day-old male neonate born with a “rash.” The patient was born to a 34-year-old gravida 3, para 2, woman at 39 weeks’ gestation. The mother’s prenatal laboratory values were within reference range and ultrasounds were normal, and she was compliant with her prenatal care. She underwent a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery 3 hours after rupture of membranes without complication. The amniotic fluid and umbilical cord both were clear. There was no use of forceps or any other external aiding devices during the delivery. At the time of delivery, the consulting physician noted that the patient had “skin lesions from head to toe.”

The patient’s parents reported that the rash did not seem to cause any discomfort for the patient. In the 24 hours after birth, the parents reported that the erythema seemed to slightly fade. Physical examination revealed many scattered erythematous to violaceous, nonblanching papulonodules affecting the scalp (Figure 1), face, arms, hands (Figure 2A), back (Figure 2B), buttocks, legs, and feet. Some of the papulonodules were soft while others were firm and indurated. Several lesions had a yellowish hue with some overlying crust. There was no mucosal, genital, or ocular involvement. No erosions, ulcerations, petechiae, ecchymoses, or hepatosplenomegaly were noted on examination.

The patient was otherwise healthy with an Apgar score of 8/9 at 1 and 5 minutes. His birth weight, length, and head circumference were within normal limits. There was no evidence of ABO blood group or Rhesus factor incompatibility. His temperature, vital signs, laboratory values (including calcium level and TORCH titers, which included cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis, and herpes simplex virus), and review of systems all were within reference range. A bone survey of the skull, spine, ribs, arms, pelvis, legs, and feet was within normal limits.

The mother’s placenta was sent for pathology and revealed a lymphoplasmacytic chronic deciduitis and acute subchorionitis consistent with a nonspecific inflammatory response, unlikely to be from an infectious etiology.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the left thigh and revealed a predominately lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils and erythrocyte precursors (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining was performed showing that the majority of the lymphocytes represented T lymphocytes, which stained positive for CD45 and CD3 and negative for S-100, CD1a, CD30, and CD117. There were scattered CD34+ cells, and scattered cells stained positive for myeloperoxidase. No significant CD20 immunoreactivity was noted. There were scattered eosinophils and rare normoblasts but no megakaryocytes. A complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential and reticulocyte count was within reference range.

At 1-, 3-, 8-, 12-, and 28-week follow-up visits, the patient continued to grow and feed appropriately. No new lesions developed during this time, and the preexisting lesions continued to fade into slightly hyperpigmented patches without induration (Figure 4). At 6 months of age, a CBC performed at the time of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), a reticulocyte count of 0.8% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%), and a lactate dehydrogenase level of 424 U/L (reference range, 100–200 U/L). All red blood cell (RBC) indices were within reference range. Flow cytometry, eosin-5-maleimide, and ektacytometry were performed with results consistent with mild hereditary spherocytosis.

Comment

Dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis is a normal component of embryologic development up until the fifth month of gestation.1 The term blueberry muffin rash typically is used to describe the cutaneous manifestations of extramedullary hematopoiesis, which commonly is caused by a TORCH infection or hematologic dyscrasia.2 It has been suggested that the term be expanded to include neoplastic processes (eg, neuroblastomas) and vascular processes (eg, multiple hemangiomas, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, glomangiomas, multifocal lymphangionendotheliomatosis), which although not associated with an extramedullary hematopoiesis, can clinically resemble a blueberry muffin rash.

Because of the potential for serious systemic complications, a cause must be sought for all newborns presenting with a blueberry muffin rash. Our patient’s lack of cardiovascular, otic, and ocular involvement combined with a negative TORCH screen and normal CBC strongly suggested against a TORCH infection. In addition, a normal bone survey and CBC, as well as a lack of petechiae, ecchymoses, and hepatosplenomegaly, were evidence against congenital leukemia.3 With the spontaneously resolving lesions and apparent clinical resolution, a bone marrow biopsy was not performed. The skin biopsy revealed negative staining for S-100 and CD1a, making the diagnosis of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis unlikely. No panniculitis was noted and calcium levels were normal, ruling out subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. The predominantly T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate demonstrated on skin biopsy led us to a differential diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis versus idiopathic dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis; however, normocytic anemia was later identified when the patient’s hemoglobin level dropped to 9.9 g/dL. The abnormal eosin-5-maleimide and ektacytometry results unmasked a hereditary spherocytosis.

Hereditary spherocytosis typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and may be caused by mutations in ankyrin-1, band 3, spectrin, or protein 4.2 on the erythrocyte membrane. It is the third leading cause of hemolytic anemia in newborns and the leading cause of direct Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion in neonates. It is most common in neonates of Northern European ancestry, affecting 1 in every 1000 to 2000 births.4 Presentation may range from asymptomatic to severe anemia with hydrops fetalis. Most neonates have an elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin and low mean corpuscular volume. Acute illness may cause hemolytic or aplastic crises, possibly explaining our patient’s normocytic anemia discovered on a CBC during an episode of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media.

Treatment options for hereditary spherocytosis include phototherapy for jaundiced neonates, folate supplementation, packed erythrocyte transfusions for symptomatic anemia, and recombinant erythropoietin in neonates.4 Splenectomy is curative for the majority of patients and requires immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis several weeks preoperatively. Patients with symptomatic gallstones may be treated with cholecystectomy at the time of splenectomy or by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy, cholecystostomy, or extracorporeal cholecystolithotripsy.5

Although a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms dermal hematopoiesis, extramedullary hematopoiesis, hereditary spherocytosis, and blueberry muffin rash yielded only 1 other known case of blueberry muffin rash caused by hereditary spherocytosis,6 other case reports demonstrate extramedullary hematopoiesis in hereditary spherocytosis patients in locations other than the skin. Calhoun et al7 described a case of a 9-year-old boy with hereditary spherocytosis who presented with jaundice. Pathologic examination revealed a 5-cm suprarenal mass demonstrating extramedullary hematopoiesis.7 A case reported by Xiros et al8 described a 64-year-old man with a history of hereditary spherocytosis who presented with hemothorax from paravertebral extramedullary hematopoiesis. De Backer et al9 reported a case of a 60-year-old man diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis after an abnormal CBC who was subsequently found to have paravertebral masses containing extramedullary hematopoiesis.

There is one known case of a blueberry muffin rash caused by hereditary spherocytosis.6 A female neonate was born at 38 weeks’ gestation with multiple petechiae and faint purpuric papules. Initial complications included intracranial ventricular hemorrhage, hyperbilirubinemia, and anemia requiring blood transfusions on the first day of life. TORCH titers were negative and a skin biopsy demonstrated a diffuse infiltrate of mature RBCs, normoblasts, and pronormoblasts in the reticular dermis. She was healthy until 3 months of age when she had several days of vomiting and diarrhea. Laboratory workup revealed a hematocrit level of 20.5% (reference range, 41%–50%); a reticulocyte count of 22.6% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%); and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating polychromatophilia, anisocytosis, and spherocytosis. She was then diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis.6

Hereditary spherocytosis is a known, albeit rare, cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis presenting as blueberry muffin rash. Patients with mild hereditary spherocytosis may have a compensated hemolysis without anemia or spherocytes on peripheral smear, which may explain the lack of severe hemolytic anemia or RBC-predominant pathology in our patient.5 Argyle and Zone6 proposed that severe hemolysis and hypoxia were the cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis in their patient. Because our patient did not experience a notable hemolytic episode until he had an upper respiratory infection and otitis media at 6 months of age, the pathophysiology is less clear; a compensated hemolytic process may underlie the extramedullary hematopoiesis and normal RBC indices.

Regardless of the precise cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis in our patient, this case of a T lymphocyte–dominant cutaneous infiltrate in a patient with mild hereditary spherocytosis is exceptionally rare and leads us to consider that perhaps there are causes of this pathology that are unknown to us.

- Zhang IH, Zane LT, Braun BS, et al. Congenital leukemia cutis with subsequent development of leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S22–S27.

- Karmegaraj B, Vijayakumar S, Ramanathan R, et al. Extramedullary haematopoiesis resembling a blueberry muffin, in a neonate. BMJ Case Rep. pii: bcr2014208473. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-208473.

- Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Neonatal leukaemia cutis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1884-1889.

- Christensen RD, Yaish HM, Gallagher PG. A pediatrician’s practical guide to diagnosing and treating hereditary spherocytosis in neonates. Pediatrics. 2015;135:1107-1114.

- Perrotta S, Gallagher PG, Mohandas N. Hereditary spherocytosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1411-1426.

- Argyle JC, Zone JJ. Dermal erythropoiesis in a neonate. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:492-494.

- Calhoun SK, Murphy RC, Shariati N, et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis in a child with hereditary spherocytosis: an uncommon cause of an adrenal mass. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:879-881.

- Xiros N, Economopoulos T, Papageorgiou E, et al. Massive hemothorax due to intrathoracic extramedullary hematopoiesis in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:38-40.

- De Backer AI, Zachée P, Vanschoubroeck IJ, et al. Extramedullary paraspinal hematopoiesis in hereditary spherocytosis. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:206-208.

- Zhang IH, Zane LT, Braun BS, et al. Congenital leukemia cutis with subsequent development of leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S22–S27.

- Karmegaraj B, Vijayakumar S, Ramanathan R, et al. Extramedullary haematopoiesis resembling a blueberry muffin, in a neonate. BMJ Case Rep. pii: bcr2014208473. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-208473.

- Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Neonatal leukaemia cutis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1884-1889.

- Christensen RD, Yaish HM, Gallagher PG. A pediatrician’s practical guide to diagnosing and treating hereditary spherocytosis in neonates. Pediatrics. 2015;135:1107-1114.

- Perrotta S, Gallagher PG, Mohandas N. Hereditary spherocytosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1411-1426.

- Argyle JC, Zone JJ. Dermal erythropoiesis in a neonate. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:492-494.

- Calhoun SK, Murphy RC, Shariati N, et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis in a child with hereditary spherocytosis: an uncommon cause of an adrenal mass. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:879-881.

- Xiros N, Economopoulos T, Papageorgiou E, et al. Massive hemothorax due to intrathoracic extramedullary hematopoiesis in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:38-40.

- De Backer AI, Zachée P, Vanschoubroeck IJ, et al. Extramedullary paraspinal hematopoiesis in hereditary spherocytosis. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:206-208.

Practice Points

- The term blueberry muffin rash is used to describe the clinical presentation of dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis. The common culprits of this rash include a TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) infection or hematologic dyscrasia.

- Because of the potential for serious systemic complications, a cause must be sought for all newborns presenting with a blueberry muffin rash.

- Hereditary spherocytosis typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and may be caused by mutations in ankyrin-1, band 3, spectrin, or protein 4.2 on the erythrocyte membrane. It is the third leading cause of hemolytic anemia in newborns and the leading cause of direct Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion in neonates.

- Treatment options for hereditary spherocytosis include phototherapy for jaundiced neonates, folate supplementation, packed erythrocyte transfusions for symptomatic anemia, and recombinant erythropoietin in neonates.

A new papule and “age spots”

An 87-year-old woman came to the office for evaluation of a lesion above her lip (FIGURE 1) that had “been there a while” and had intermittently been bleeding and crusting for the last few months. On examination, there was a distinct, firm (but not hard) papule with some adjacent erythema. No distinct telangiectasias, ulceration, blood, or crusts were visible with handheld magnification or upon dermoscopy. (see “The digital camera: Another stethoscope for the skin,”)

FIGURE 1

Lesion above lip

An evaluation of the remainder of the woman’s face revealed 3 more lesions that the patient termed “age spots.” They had been present for quite some time, had not had any notable rapid change, and had not caused her (or a physician in the family) any concern. These “age spots” are depicted in (FIGURE 2A) (left temple), (FIGURE 2B) (forehead), and (FIGURE 2C) (left cheek). Digital photographs were taken through the dermatoscope of the temple, forehead, and cheek lesions (FIGURE 3A, B, AND C).

FIGURE 2A

Digital photos

FIGURE 2B

Digital photos

FIGURE 2C

Digital photos

The 4 lesions are easily identified as worrisome, given that they were pigmented and asymmetric, with a variety of bizarre colors.

The lip. In particular, the lesion above the upper lip (FIGURE 1) clinically presented a wide range of possibilities, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), milial cyst, nevus, trichoepithelioma, fibrous papule, or any of a variety of adnexal skin neoplasms. Knowing that the lesion was relatively new and had bled and crusted was sufficient to warrant biopsy.

The temple. Dermoscopically, the temple lesion (FIGURE 3A) had blue and brown ovoid structures (also called “blebs” or “blobs”), white areas within the lesion (whiter than normal surrounding skin), a high degree of asymmetry, and distinct telangiectatic vessels. The pink color on dermoscopy was also a cause for concern. The blue ovoid structures plus telangiectasias were highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3A

Dermoscopy images

The forehead. Dermoscopy of the forehead lesion (FIGURE 3B) showed leaf-like structures (12 o’clock) and maple-leaf structures (6 o’clock). These alone were highly suggestive of pigmented basal cell carcinoma—but in the absence of distinct telangiectasias, we decided to do a deep incisional biopsy rather than risk potentially “shaving a melanoma.” (If a melanoma is biopsied via a shave technique, the ability to histologically measure its thickness and to stage it according to Clark and Breslow staging is lost.)

FIGURE 3B

Dermoscopy images

The cheek. Dermoscopically, the lesion on the cheek (FIGURE 3C) also had no obvious telangiectasias but had a “spoke-wheel” structure (6 o’clock) highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3C

Dermoscopy images

All the lesions—except for the temple lesion, which was biopsied via a shave technique—were biopsied via generous incisional ellipses.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histology confirmed that all 4 lesions were basal cell carcinomas, the most common type of skin malignancy. The temple lesion in Figures 2A AND 3A and the forehead lesion in Figures 2B AND 3B were histologically both pigmented nodular basal cell carcinomas, clinically characterized as pearly papules with pigment. (FIGURE 3A) also demonstrates telangiectasia.

Differential diagnosis: Innocent papule or carcinoma?

The lip lesion, the presenting “symptom,” did not have evident bleeding and crusting on visual or dermoscopic examination. In the absence of a complete history, it could have been “passed off” as an innocent papule, such as a molluscum (though not common in the elderly) or a milial or epidermoid cyst.

Remember that basal cell carcinoma can be subtle. These lesions were missed by a patient and her family—which included a physician within the household—and grew slowly enough that the patient felt they were simply “age spots.” We have seen basal cell carcinomas that patients have indicated have not changed in years—have not bled, ulcerated, or crusted, while symptomatic lesions have been the least impressive, clinically, at the time of the exam. Always maintain a high index of suspicion.

The clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and their dermoscopic findings are summarized in the (TABLE).

TABLE

Clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and dermoscopic findings

| CLINICAL TYPE | DERMOSCOPIC FINDINGS | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

Nodular (including noduloulcerative and cystic) “Wart” on a supraclavicular area—note pearly translucency of nodular basal cell carcinoma. | Arborizing (tree-like branching telangiectasias) Dermoscopy of lesion at left, clearly showing arborized telangiectatic vessels. |

|

| Pigmented |

|

|

| Sclerosing, cicatricial, or morpheaform | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| Superficial | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| *Sensitivity/specificity. Sensitivity is the percentage of basal cell carcinomas that possess the feature. Specificity listed is the percentage of melanomas that lack the feature.1 All discussion of dermoscopic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma assumes absence of a melanocytic pigment network, the presence of which suggests a melanocytic lesion such as a nevus, lentigo, or melanoma. | ||

| Note: The primary use of dermoscopy is the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Thus, except to aid in visualization of telangiectasias and ulceration, there are no characteristic dermoscopic findings in other types of basal cell carcinoma. Telangiectasias may not be visualized if the dermatoscope is applied with sufficient pressure to blanch them. Basal cell carcinomas may exhibit no definite or suggestive findings by dermoscopy, as was the case with the lip papule on this patient. | ||

Tips for making an accurate diagnosis

Basal cell carcinoma and melanoma can mimic other lesions, so keep these tips in mind:

- The “company” a lesion keeps sometimes can help in diagnosis. A patient may have a group of small “pearly papules,” only one of which may show the typical umbilication that allows a confident diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum, for example. Here, 3 lesions had similar dermoscopic structures, only one of which exhibited telangiectasia. A fourth lesion lacked diagnostic characteristics. The best guess, based on the sum total appearance of all of these lesions, is that all are basal cell carcinomas because of the “company they are keeping”—but note that this is also potentially a trap: missing the single basal cell carcinoma lesion among a field of sebaceous hyperplasia, for instance.

- Don’t focus exclusively on the symptomatic lesion. Do a survey of the general region. For ultraviolet-associated lesions (including basal cell carcinoma), it’s preferable to perform, at minimum, a survey of “high-radiation” areas (face, exposed scalp, neck, ears, and dorsal hands and forearms) for other ultraviolet “damage” (eg, actinic keratoses).

- Be meticulous when examining patients’ backs. Patients may not spot lesions on their backs—especially if they are older and have poor vision.

- Avoid thinking in terms of absolutes like “never” and “always.” The clinical axiom that basal cell carcinomas “never” have hair growing from them is disproved by (FIGURE 3A), which clinically, dermoscopically, and histologically is a basal cell carcinoma lesion. Some of the hair seen here is overlying, loose scalp hair “caught” in the dermoscopic field because of the location of this lesion on the temple adjacent to the hairline. But there are also very distinct hairs seen coming out from areas (at about 6 and 8 o’clock) that are clearly part of the lesion, especially on its periphery.

When in doubt, biopsy

When in doubt about which technique to perform, do an incisional biopsy—preferably excisional, but at least a good sampling of the most worrisome area(s).

Suspected basal cell carcinoma, when the examiner is confident the lesion is not a melanoma, can be further evaluated by superficial shave biopsy. Potential melanoma generally should not be evaluated by the shave technique.

Options for therapy

Therapy options for basal cell carcinoma vary based on location (high-risk vs low-risk locations), histologic type of basal cell carcinoma, patient preference, and local availability of therapy. The primary therapies for basal cell carcinoma are surgical excision (including Mohs surgery) and curettage, often combined with electrodesiccation. 5-flurouracil (5-FU) should not be used because it can treat the surface tumor while deeper tumor proliferates.3 Imiquimod is not approved for facial lesions or nodular basal cell carcinomas.

While dermatoscopes are the true “skin stethoscopes,” most primary care physicians do not have them. Many, however, do have a digital camera. A digital camera with a macro-focus feature can be viewed as another stethoscope for the skin. Pictures allow great magnification on the computer screen, presenting color and detail that may be missed on routine clinical inspection. They allow an unhurried “self–second opinion”; you can evaluate lesions with no motion, breathing, or other distractions, following the office visit.

Digital images may also be important for:

- the patient, who may not be able to see the lesion, because it’s on his back, buttocks, or behind his ears. Consider, too, the older patient who may not be able to see the seborrhea in his eyebrow with his bifocals, but he can see it on the camera’s monitor.

- the medical record (printed or electronically stored).

- the pathologist—when forwarded with the pathology specimen. The images can be helpful in developing a clinical correlation to include in the pathology report.

- the insurance carrier, as indisputable documentation for the clinical rationale for biopsying 4 lesions on 1 visit in the event of a “Dear Bad Doctor” Medicare letter. In fact, if not for the indisputable photographic record, one author (GNF) would have been extremely hesitant to perform 4 biopsies on a Medicare patient in 1 session.

- light and magnification where the 2 may be in short supply, such as a poorly mobile patient in a hospital bed. A camera with flash, auto-focus, and macro mode may allow access to otherwise inaccessible lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Gary N. Fox wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Lisa Nichols for their help with portions of this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2458 Willesden Green, Toledo, OH. E-mail: foxgary@yahoo.com

1. Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

2. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004.

3. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors [chapter 21]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004.

An 87-year-old woman came to the office for evaluation of a lesion above her lip (FIGURE 1) that had “been there a while” and had intermittently been bleeding and crusting for the last few months. On examination, there was a distinct, firm (but not hard) papule with some adjacent erythema. No distinct telangiectasias, ulceration, blood, or crusts were visible with handheld magnification or upon dermoscopy. (see “The digital camera: Another stethoscope for the skin,”)

FIGURE 1

Lesion above lip

An evaluation of the remainder of the woman’s face revealed 3 more lesions that the patient termed “age spots.” They had been present for quite some time, had not had any notable rapid change, and had not caused her (or a physician in the family) any concern. These “age spots” are depicted in (FIGURE 2A) (left temple), (FIGURE 2B) (forehead), and (FIGURE 2C) (left cheek). Digital photographs were taken through the dermatoscope of the temple, forehead, and cheek lesions (FIGURE 3A, B, AND C).

FIGURE 2A

Digital photos

FIGURE 2B

Digital photos

FIGURE 2C

Digital photos

The 4 lesions are easily identified as worrisome, given that they were pigmented and asymmetric, with a variety of bizarre colors.

The lip. In particular, the lesion above the upper lip (FIGURE 1) clinically presented a wide range of possibilities, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), milial cyst, nevus, trichoepithelioma, fibrous papule, or any of a variety of adnexal skin neoplasms. Knowing that the lesion was relatively new and had bled and crusted was sufficient to warrant biopsy.

The temple. Dermoscopically, the temple lesion (FIGURE 3A) had blue and brown ovoid structures (also called “blebs” or “blobs”), white areas within the lesion (whiter than normal surrounding skin), a high degree of asymmetry, and distinct telangiectatic vessels. The pink color on dermoscopy was also a cause for concern. The blue ovoid structures plus telangiectasias were highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3A

Dermoscopy images

The forehead. Dermoscopy of the forehead lesion (FIGURE 3B) showed leaf-like structures (12 o’clock) and maple-leaf structures (6 o’clock). These alone were highly suggestive of pigmented basal cell carcinoma—but in the absence of distinct telangiectasias, we decided to do a deep incisional biopsy rather than risk potentially “shaving a melanoma.” (If a melanoma is biopsied via a shave technique, the ability to histologically measure its thickness and to stage it according to Clark and Breslow staging is lost.)

FIGURE 3B

Dermoscopy images

The cheek. Dermoscopically, the lesion on the cheek (FIGURE 3C) also had no obvious telangiectasias but had a “spoke-wheel” structure (6 o’clock) highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3C

Dermoscopy images

All the lesions—except for the temple lesion, which was biopsied via a shave technique—were biopsied via generous incisional ellipses.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histology confirmed that all 4 lesions were basal cell carcinomas, the most common type of skin malignancy. The temple lesion in Figures 2A AND 3A and the forehead lesion in Figures 2B AND 3B were histologically both pigmented nodular basal cell carcinomas, clinically characterized as pearly papules with pigment. (FIGURE 3A) also demonstrates telangiectasia.

Differential diagnosis: Innocent papule or carcinoma?

The lip lesion, the presenting “symptom,” did not have evident bleeding and crusting on visual or dermoscopic examination. In the absence of a complete history, it could have been “passed off” as an innocent papule, such as a molluscum (though not common in the elderly) or a milial or epidermoid cyst.

Remember that basal cell carcinoma can be subtle. These lesions were missed by a patient and her family—which included a physician within the household—and grew slowly enough that the patient felt they were simply “age spots.” We have seen basal cell carcinomas that patients have indicated have not changed in years—have not bled, ulcerated, or crusted, while symptomatic lesions have been the least impressive, clinically, at the time of the exam. Always maintain a high index of suspicion.

The clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and their dermoscopic findings are summarized in the (TABLE).

TABLE

Clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and dermoscopic findings

| CLINICAL TYPE | DERMOSCOPIC FINDINGS | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

Nodular (including noduloulcerative and cystic) “Wart” on a supraclavicular area—note pearly translucency of nodular basal cell carcinoma. | Arborizing (tree-like branching telangiectasias) Dermoscopy of lesion at left, clearly showing arborized telangiectatic vessels. |

|

| Pigmented |

|

|

| Sclerosing, cicatricial, or morpheaform | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| Superficial | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| *Sensitivity/specificity. Sensitivity is the percentage of basal cell carcinomas that possess the feature. Specificity listed is the percentage of melanomas that lack the feature.1 All discussion of dermoscopic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma assumes absence of a melanocytic pigment network, the presence of which suggests a melanocytic lesion such as a nevus, lentigo, or melanoma. | ||

| Note: The primary use of dermoscopy is the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Thus, except to aid in visualization of telangiectasias and ulceration, there are no characteristic dermoscopic findings in other types of basal cell carcinoma. Telangiectasias may not be visualized if the dermatoscope is applied with sufficient pressure to blanch them. Basal cell carcinomas may exhibit no definite or suggestive findings by dermoscopy, as was the case with the lip papule on this patient. | ||

Tips for making an accurate diagnosis

Basal cell carcinoma and melanoma can mimic other lesions, so keep these tips in mind:

- The “company” a lesion keeps sometimes can help in diagnosis. A patient may have a group of small “pearly papules,” only one of which may show the typical umbilication that allows a confident diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum, for example. Here, 3 lesions had similar dermoscopic structures, only one of which exhibited telangiectasia. A fourth lesion lacked diagnostic characteristics. The best guess, based on the sum total appearance of all of these lesions, is that all are basal cell carcinomas because of the “company they are keeping”—but note that this is also potentially a trap: missing the single basal cell carcinoma lesion among a field of sebaceous hyperplasia, for instance.