User login

Investigators analyzed data for almost 13,000 working-age adults with ADHD and found ADHD medication use during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year.

In addition, among the female participants, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk for subsequent long-term unemployment. In both genders, within-individual comparisons showed long-term unemployment was lower during periods of ADHD medication treatment, compared with nontreatment periods.

“This evidence should be considered together with the existing knowledge of risks and benefits of ADHD medications when developing treatment plans for working-aged adults,” lead author Lin Li, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the School of Medical Science, Örebro University, Sweden, told this news organization.

“However, the effect size is relatively small in magnitude, indicating that other treatment programs, such as psychotherapy, are also needed to help individuals with ADHD in work-related settings,” Ms. Li said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Evidence gap

Adults with ADHD “have occupational impairments, such as poor work performance, less job stability, financial problems, and increased risk for unemployment,” the investigators write.

However, “less is known about the extent to which pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with reductions in unemployment rates,” they add.

“People with ADHD have been reported to have problems in work-related performance,” Ms. Li noted. “ADHD medications could reduce ADHD symptoms and also help with academic achievement, but there is limited evidence on the association between ADHD medication and occupational outcomes.”

To address this gap in evidence, the researchers turned to several major Swedish registries to identify 25,358 individuals with ADHD born between 1958 and 1978 who were aged 30 to 55 years during the study period of Jan. 1, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2013).

Of these, 12,875 (41.5% women; mean age, 37.9 years) were included in the analysis. Most participants (81.19%) had more than 9 years of education.

The registers provided information not only about diagnosis, but also about prescription medications these individuals took for ADHD, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and atomoxetine.

Administrative records provided data about yearly accumulated unemployment days, with long-term unemployment defined as having at least 90 days of unemployment in a calendar year.

Covariates included age at baseline, sex, country of birth, highest educational level, crime records, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Most patients (69.34%) had at least one psychiatric comorbidity, with depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders being the most common (in 40.28%, 35.27%, and 28.77%, respectively).

Symptom reduction

The mean length of medication use was 49 days (range, 0-366 days) per year. Of participants in whom these data were available, 31.29% of women and 31.03% of men never used ADHD medications. Among participants treated with ADHD medication (68.71%), only 3.23% of the women and 3.46% of the men had persistent use during the follow-up period.

Among women and men in whom these data were available, (38.85% of the total sample), 35.70% and 41.08%, respectively, were recorded as having one or more long-term unemployment stretches across the study period. In addition, 0.15% and 0.4%, respectively, had long-term unemployment during each of those years.

Use of ADHD medications during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year (adjusted relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.87-0.95).

The researchers also found an association between use of ADHD medications and long-term unemployment among women (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76-0.89) but not among men (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.01).

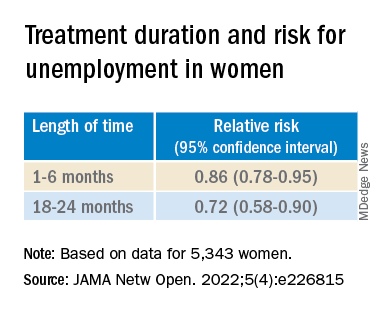

Among women in particular, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk of subsequent long-term unemployment (P < .001 for trend).

Within-individual comparisons showed the long-term unemployment rate was lower during periods when individuals were being treated with ADHD medication vs. periods of nontreatment (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85-0.94).

“Among 12,875 working-aged adults with ADHD in Sweden, we found the use of ADHD medication is associated with a lower risk of long-term unemployment, especially for women,” Ms. Li said.

“The hypothesis of this study is that ADHD medications are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, which may in turn help to improve work performance among individuals with ADHD,” she added.

However, Ms. Li cautioned, “the information on ADHD symptoms is not available in Swedish National Registers, so more research is needed to test the hypothesis.”

The investigators also suggest that future research “should further explore the effectiveness of stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications” and replicate their findings in other settings.

Findings ‘make sense’

Commenting on the study, Ari Tuckman PsyD, expert spokesman for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, said, there is “a lot to like about this study, specifically the large sample size and within-individual comparisons that the Scandinavians’ databases allow.”

“We know that ADHD can impact both finding and keeping a job, so it absolutely makes sense that medication use would reduce duration of unemployment,” said Dr. Tuckman, who is in private practice in West Chester, Pa., and was not involved with the research.

However, “I would venture that the results would have been more robust if the authors had been able to only look at those on optimized medication regimens, which is far too few,” he added. “This lack of optimization would have been even more true 10 years ago, which is when the data was from.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, an award from the Swedish Research Council, and a grant from Shire International GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. Ms. Li and Dr. Tuckman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 13,000 working-age adults with ADHD and found ADHD medication use during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year.

In addition, among the female participants, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk for subsequent long-term unemployment. In both genders, within-individual comparisons showed long-term unemployment was lower during periods of ADHD medication treatment, compared with nontreatment periods.

“This evidence should be considered together with the existing knowledge of risks and benefits of ADHD medications when developing treatment plans for working-aged adults,” lead author Lin Li, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the School of Medical Science, Örebro University, Sweden, told this news organization.

“However, the effect size is relatively small in magnitude, indicating that other treatment programs, such as psychotherapy, are also needed to help individuals with ADHD in work-related settings,” Ms. Li said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Evidence gap

Adults with ADHD “have occupational impairments, such as poor work performance, less job stability, financial problems, and increased risk for unemployment,” the investigators write.

However, “less is known about the extent to which pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with reductions in unemployment rates,” they add.

“People with ADHD have been reported to have problems in work-related performance,” Ms. Li noted. “ADHD medications could reduce ADHD symptoms and also help with academic achievement, but there is limited evidence on the association between ADHD medication and occupational outcomes.”

To address this gap in evidence, the researchers turned to several major Swedish registries to identify 25,358 individuals with ADHD born between 1958 and 1978 who were aged 30 to 55 years during the study period of Jan. 1, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2013).

Of these, 12,875 (41.5% women; mean age, 37.9 years) were included in the analysis. Most participants (81.19%) had more than 9 years of education.

The registers provided information not only about diagnosis, but also about prescription medications these individuals took for ADHD, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and atomoxetine.

Administrative records provided data about yearly accumulated unemployment days, with long-term unemployment defined as having at least 90 days of unemployment in a calendar year.

Covariates included age at baseline, sex, country of birth, highest educational level, crime records, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Most patients (69.34%) had at least one psychiatric comorbidity, with depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders being the most common (in 40.28%, 35.27%, and 28.77%, respectively).

Symptom reduction

The mean length of medication use was 49 days (range, 0-366 days) per year. Of participants in whom these data were available, 31.29% of women and 31.03% of men never used ADHD medications. Among participants treated with ADHD medication (68.71%), only 3.23% of the women and 3.46% of the men had persistent use during the follow-up period.

Among women and men in whom these data were available, (38.85% of the total sample), 35.70% and 41.08%, respectively, were recorded as having one or more long-term unemployment stretches across the study period. In addition, 0.15% and 0.4%, respectively, had long-term unemployment during each of those years.

Use of ADHD medications during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year (adjusted relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.87-0.95).

The researchers also found an association between use of ADHD medications and long-term unemployment among women (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76-0.89) but not among men (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.01).

Among women in particular, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk of subsequent long-term unemployment (P < .001 for trend).

Within-individual comparisons showed the long-term unemployment rate was lower during periods when individuals were being treated with ADHD medication vs. periods of nontreatment (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85-0.94).

“Among 12,875 working-aged adults with ADHD in Sweden, we found the use of ADHD medication is associated with a lower risk of long-term unemployment, especially for women,” Ms. Li said.

“The hypothesis of this study is that ADHD medications are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, which may in turn help to improve work performance among individuals with ADHD,” she added.

However, Ms. Li cautioned, “the information on ADHD symptoms is not available in Swedish National Registers, so more research is needed to test the hypothesis.”

The investigators also suggest that future research “should further explore the effectiveness of stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications” and replicate their findings in other settings.

Findings ‘make sense’

Commenting on the study, Ari Tuckman PsyD, expert spokesman for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, said, there is “a lot to like about this study, specifically the large sample size and within-individual comparisons that the Scandinavians’ databases allow.”

“We know that ADHD can impact both finding and keeping a job, so it absolutely makes sense that medication use would reduce duration of unemployment,” said Dr. Tuckman, who is in private practice in West Chester, Pa., and was not involved with the research.

However, “I would venture that the results would have been more robust if the authors had been able to only look at those on optimized medication regimens, which is far too few,” he added. “This lack of optimization would have been even more true 10 years ago, which is when the data was from.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, an award from the Swedish Research Council, and a grant from Shire International GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. Ms. Li and Dr. Tuckman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 13,000 working-age adults with ADHD and found ADHD medication use during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year.

In addition, among the female participants, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk for subsequent long-term unemployment. In both genders, within-individual comparisons showed long-term unemployment was lower during periods of ADHD medication treatment, compared with nontreatment periods.

“This evidence should be considered together with the existing knowledge of risks and benefits of ADHD medications when developing treatment plans for working-aged adults,” lead author Lin Li, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the School of Medical Science, Örebro University, Sweden, told this news organization.

“However, the effect size is relatively small in magnitude, indicating that other treatment programs, such as psychotherapy, are also needed to help individuals with ADHD in work-related settings,” Ms. Li said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Evidence gap

Adults with ADHD “have occupational impairments, such as poor work performance, less job stability, financial problems, and increased risk for unemployment,” the investigators write.

However, “less is known about the extent to which pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with reductions in unemployment rates,” they add.

“People with ADHD have been reported to have problems in work-related performance,” Ms. Li noted. “ADHD medications could reduce ADHD symptoms and also help with academic achievement, but there is limited evidence on the association between ADHD medication and occupational outcomes.”

To address this gap in evidence, the researchers turned to several major Swedish registries to identify 25,358 individuals with ADHD born between 1958 and 1978 who were aged 30 to 55 years during the study period of Jan. 1, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2013).

Of these, 12,875 (41.5% women; mean age, 37.9 years) were included in the analysis. Most participants (81.19%) had more than 9 years of education.

The registers provided information not only about diagnosis, but also about prescription medications these individuals took for ADHD, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and atomoxetine.

Administrative records provided data about yearly accumulated unemployment days, with long-term unemployment defined as having at least 90 days of unemployment in a calendar year.

Covariates included age at baseline, sex, country of birth, highest educational level, crime records, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Most patients (69.34%) had at least one psychiatric comorbidity, with depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders being the most common (in 40.28%, 35.27%, and 28.77%, respectively).

Symptom reduction

The mean length of medication use was 49 days (range, 0-366 days) per year. Of participants in whom these data were available, 31.29% of women and 31.03% of men never used ADHD medications. Among participants treated with ADHD medication (68.71%), only 3.23% of the women and 3.46% of the men had persistent use during the follow-up period.

Among women and men in whom these data were available, (38.85% of the total sample), 35.70% and 41.08%, respectively, were recorded as having one or more long-term unemployment stretches across the study period. In addition, 0.15% and 0.4%, respectively, had long-term unemployment during each of those years.

Use of ADHD medications during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year (adjusted relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.87-0.95).

The researchers also found an association between use of ADHD medications and long-term unemployment among women (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76-0.89) but not among men (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.01).

Among women in particular, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk of subsequent long-term unemployment (P < .001 for trend).

Within-individual comparisons showed the long-term unemployment rate was lower during periods when individuals were being treated with ADHD medication vs. periods of nontreatment (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85-0.94).

“Among 12,875 working-aged adults with ADHD in Sweden, we found the use of ADHD medication is associated with a lower risk of long-term unemployment, especially for women,” Ms. Li said.

“The hypothesis of this study is that ADHD medications are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, which may in turn help to improve work performance among individuals with ADHD,” she added.

However, Ms. Li cautioned, “the information on ADHD symptoms is not available in Swedish National Registers, so more research is needed to test the hypothesis.”

The investigators also suggest that future research “should further explore the effectiveness of stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications” and replicate their findings in other settings.

Findings ‘make sense’

Commenting on the study, Ari Tuckman PsyD, expert spokesman for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, said, there is “a lot to like about this study, specifically the large sample size and within-individual comparisons that the Scandinavians’ databases allow.”

“We know that ADHD can impact both finding and keeping a job, so it absolutely makes sense that medication use would reduce duration of unemployment,” said Dr. Tuckman, who is in private practice in West Chester, Pa., and was not involved with the research.

However, “I would venture that the results would have been more robust if the authors had been able to only look at those on optimized medication regimens, which is far too few,” he added. “This lack of optimization would have been even more true 10 years ago, which is when the data was from.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, an award from the Swedish Research Council, and a grant from Shire International GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. Ms. Li and Dr. Tuckman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN