User login

Malignant melanoma is the most serious form of primary skin cancer and one of the only malignancies in which the incidence rate has been rising. It is estimated that in 2018 there were 91,270 newly diagnosed cases and 9320 deaths from advanced melanoma in the United States. Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer type in males and the sixth most common in females. Despite rising incidence rates, improvement in the treatment of advanced melanoma has resulted in declining death rates over the past decade.1 Although most melanoma is diagnosed at an early stage and can be cured with surgical excision, the prognosis for metastatic melanoma had been historically poor prior to recent advancements in treatment. Conventional chemotherapy treatment with dacarbazine or temozolomide resulted in response rates ranging from 7.5% to 12.1%, but without much impact on median overall survival (OS), with reported OS ranging from 6.4 to 7.8 months. Combination approaches with interferon alfa-2B and low-dose interleukin-2 resulted in improved response rates compared with traditional chemotherapy, but again without survival benefit.2

Immunotherapy in the form of high-dose interleukin-2 emerged as the first therapy to alter the natural history of advanced melanoma, with both improved response rates (objective response rate [ORR], 16%) and median OS (2 months), with some patients achieving durable responses lasting more than 30 months. However, significant systemic toxicity limited its application to carefully selected patients.3 The past decade has brought rapid advancements in treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors and molecularly targeted agents, which have significantly improved ORRs, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS for patients with metastatic melanoma.4-8

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the treatment and sequencing of therapies in advanced melanoma. Here, we review the selection of first-line therapy for metastatic melanoma. Current evidence for immune checkpoint blockade and molecularly targeted agents in the treatment of metastatic melanoma after progression on first-line therapy is discussed in a separate article.

Pathogenesis

The incidence of melanoma is strongly associated with ultraviolet light–mediated DNA damage related to sun exposure. Specifically, melanoma is associated to a greater degree with intense intermittent sun exposure and sunburn, but not associated with higher occupational exposure.9 Ultraviolet radiation can induce DNA damage by a number of mechanisms, and deficient DNA repair leads to somatic mutations that drive the progression from normal melanocyte to melanoma.10

The most commonly identified genetic mutations in cutaneous melanomas are alterations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Typically, an extracellular growth factor causes dimerization of the growth factor receptor, which activates the intracellular RAS GTPase protein. Subsequently BRAF is phosphorylated within the kinase domain, which leads to downstream activation of the MEK and ERK kinases through phosphorylation. Activated ERK leads to phosphorylation of various cytoplasmic and nuclear targets, and the downstream effects of these changes promote cellular proliferation. While activation of this pathway usually requires phosphorylation of BRAF by RAS, mutations placing an acidic amino acid near the kinase domain mimics phosphorylation and leads to constitutive activation of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase in the absence of upstream signaling from extracellular growth factors mediated through RAS.11 One study of tumor samples of 71 patients with cutaneous melanoma detected NRAS mutations in 30% and BRAF mutations in 59% of all tumors tested. Of the BRAF mutation–positive tumors, 88% harbored the Val599Glu mutation, now commonly referred to as the BRAF V600E mutation. The same study demonstrated that the vast majority of BRAF mutations were seen in the primary tumor and were preserved when metastases were analyzed. Additionally, both NRAS and BRAF mutations were detected in the radial growth phase of the melanoma tumor. These findings indicate that alterations in the MAPK pathway occur early in the pathogenesis of advanced melanoma.11 Another group demonstrated that 66% of malignant melanoma tumor samples harbored BRAF mutations, of which 80% were specifically the V600E mutation. In vitro assays showed that the BRAF V600E–mutated kinase had greater than 10-fold kinase activity compared to wild-type BRAF, and that this kinase enhanced cellular proliferation even when upstream NRAS signaling was inhibited.12

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network performed a large analysis of tumor samples from 331 different melanoma patients and studied variations at the DNA, RNA, and protein levels. The study established a framework of 4 notable genomic subtypes, including mutant BRAF (52%), mutant RAS (28%), mutant NF1 (14%), and triple wild-type (6%). Additionally, mRNA transcriptomic analysis of overexpressed genes identified 3 different subclasses, which were labeled as “immune,” “keratin,” and “MITF-low.” The immune subclass was characterized by increased expression of proteins found in immune cells, immune signaling molecules, immune checkpoint proteins, cytokines, and chemokines, and correlated with increased lymphocyte invasion within the tumor. Interestingly, in the post-accession survival analysis, the “immune” transcriptomic subclass was statistically correlated with an improved prognosis.13 Having an understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of advanced melanoma helps to create a framework for understanding the mechanisms of current standard of care therapies for the disease.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old Caucasian man with a history of well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension is being followed by his dermatologist for surveillance of melanocytic nevi. On follow-up he is noted to have an asymmetrical melanocytic lesion over the right scalp with irregular borders and variegated color. He is asymptomatic and the remainder of physical examination is unremarkable, as he has no other concerning skin lesions and no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

How is melanoma diagnosed?

Detailed discussion about diagnosis and staging will be deferred in this review of treatment of advanced melanoma. In brief, melanoma is best diagnosed by excisional biopsy and histopathology. Staging of melanoma is done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition, using a TNM staging system that incorporates tumor thickness (Breslow depth); ulceration; number of involved regional lymph nodes; presence of in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases; distant metastases; and serum lactate dehydrogenase level.14

Case Continued

The patient undergoes a wide excisional biopsy of the right scalp lesion, which is consistent with malignant melanoma. Pathology demonstrates a Breslow depth of 2.6 mm, 2 mitotic figures/mm2, and no evidence of ulceration. He subsequently undergoes wide local excision with 0/3 sentinel lymph nodes positive for malignancy. His final staging is consistent with pT3aN0M0, stage IIA melanoma.

He is seen in follow-up with medical oncology for the next 3.5 years without any evidence of disease recurrence. He then develops symptoms of vertigo, diplopia, and recurrent falls, prompting medical attention. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain reveals multiple supratentorial and infratentorial lesions concerning for intracranial metastases. Further imaging with computed tomography (CT) chest/abdomen/pelvis reveals a right lower lobe pulmonary mass with right hilar and subcarinal lymphadenopathy. He is admitted for treatment with intravenous dexamethasone and further evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the right lower lobe mass, which reveals metastatic melanoma. Given the extent of his intracranial metastases, he is treated with whole brain radiation therapy for symptomatic relief prior to initiating systemic therapy.

What is the general approach to first-line treatment for metastatic melanoma?

The past decade has brought an abundance of data supporting the use of immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors or molecularly targeted therapy with combined BRAF/MEK inhibitors in the first-line setting.4-8 After the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma has been made, molecular testing is recommended to determine the BRAF status of the tumor. Immunotherapy is the clear choice for first-line therapy in the absence of an activating BRAF V600 mutation. When a BRAF V600 mutation is present, current evidence supports the use of either immunotherapy or molecularly targeted therapy as first-line therapy.

To date, there have been no prospective clinical trials comparing the sequencing of immunotherapy and molecularly targeted therapy in the first-line setting. An ongoing clinical trial (NCT02224781) is comparing dabrafenib and trametinib followed by ipilimumab and nivolumab at time of progression to ipilimumab and nivolumab followed by dabrafenib and trametinib in patients with newly diagnosed stage III/IV BRAF V600 mutation–positive melanoma. The primary outcome measure is 2-year OS. Until completion of that trial, current practice regarding which type of therapy to use in the first-line setting is based on a number of factors including clinical characteristics and provider preferences.

Data suggest that immunotherapies can produce durable responses, especially after treatment completion or discontinuation, albeit at the expense of taking a longer time to achieve clinical benefit and the risk of potentially serious immune-related adverse effects. This idea of a durable, off-treatment response is highlighted by a study that followed 105 patients who had achieved a complete response (CR) and found that 24-month disease-free survival from the time of CR was 90.9% in all patients and 89.9% in the 67 patients who had discontinued pembrolizumab after attaining CR.15 BRAF/MEK inhibition has the potential for rapid clinical responses, though concerns exist about the development of resistance to therapy. The following sections explore the evidence supporting the use of these therapies.

Immunotherapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Immunotherapy via immune checkpoint blockade has revolutionized the treatment of many solid tumors over the past decade. The promise of immunotherapy revolves around the potential for achieving a dynamic and durable systemic response against cancer by augmenting the antitumor effects of the immune system. T-cells are central to mounting a systemic antitumor response, and, in addition to antigen recognition, their function depends heavily on fine tuning between co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signaling. The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) expressed on T-cells was the first discovered co-inhibitory receptor of T-cell activation.16 Later, it was discovered that the programmed cell death 1 receptor (PD-1), expressed on T-cells, and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, expressed on antigen presenting cells, tumor cells, or other cells in the tumor microenvironment, also served as a potent negative regulator of T-cell function.17

Together, these 2 signaling pathways help to maintain peripheral immune tolerance, whereby autoreactive T-cells that have escaped from the thymus are silenced to prevent autoimmunity. However, these pathways can also be utilized by cancer cells to escape immune surveillance. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the aforementioned co-inhibitory signaling pathways, and thus augment the immune response, have proven to be an effective anticancer therapy capable of producing profound and durable responses in certain malignancies.16,17

Ipilimumab

Ipilimumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the function of the CTLA-4 co-inhibitory immune checkpoint. In a phase 3 randomized controlled trial of 676 patients with previously treated metastatic melanoma, ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 cycles, with or without a gp100 peptide vaccine, resulted in an improved median OS of 10.0 and 10.1 months, respectively, compared to 6.4 months in those receiving the peptide vaccine alone, meeting the primary endpoint.4 Subsequently, a phase 3 trial of 502 patients with untreated metastatic melanoma compared ipilimumab at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 cycles plus dacarbazine to dacarbazine plus placebo and found a significant increase in median OS (11.2 months vs 9.1 months), with no additive benefit of chemotherapy. There was a higher reported rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events in this trial with ipilimumab dosed at 10 mg/kg, which was felt to be dose-related.18 These trials were the first to show improved OS with any systemic therapy in metastatic melanoma and led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ipilimumab for this indication in 2011.

PD-1 Inhibitor Monotherapy

The PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab were initially approved for metastatic melanoma after progression on ipilimumab. In the phase 1 trial of patients with previously treated metastatic melanoma, nivolumab therapy resulted in an ORR of 28%.19 The subsequent phase 2 trial conducted in pretreated patients, including patients who had progressed on ipilimumab, confirmed a similar ORR of 31%, as well as a median PFS of 3.7 months and a median OS of 16.8 months. The estimated response duration in patients who did achieve a response to therapy was 2 years.20 A phase 3 trial (CheckMate 037) comparing nivolumab (n = 120) to investigator’s choice chemotherapy (n = 47) in those with melanoma refractory to ipilimumab demonstrated that nivolumab was superior for the primary endpoint of ORR (31.7% vs 10.6%), had less toxicity (5% rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events versus 9%), and increased median duration of response (32 months vs 13 months).21

The phase 1 trial (KEYNOTE-001) testing the efficacy of pembrolizumab demonstrated an ORR of 33% in the total population of patients treated and an ORR of 45% in those who were treatment-naive. Additionally, the median OS was 23 months for the total population and 31 months for treatment-naive patients, with only 14% of patients experiencing a grade 3 or 4 adverse event.22 The KEYNOTE-002 phase 2 trial compared 2 different pembrolizumab doses (2 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks) to investigator’s choice chemotherapy (paclitaxel plus carboplatin, paclitaxel, carboplatin, dacarbazine, or oral temozolomide) in 540 patients with advanced melanoma with documented progression on ipilimumab with or without prior progression on molecularly targeted therapy if positive for a BRAF V600 mutation. The final analysis demonstrated significantly improved ORR with pembrolizumab (22% at 2 mg/kg vs 26% at 10 mg/kg vs 4% chemotherapy) and significantly improved 24-month PFS (16% vs 22% vs 0.6%, respectively). There was a nonstatistically significant improvement in median OS (13.4 months vs 14.7 months vs 10 months), although 55% of the patients initially assigned to the chemotherapy arm crossed over and received pembrolizumab after documentation of progressive disease.23,24

Because PD-1 inhibition improved efficacy with less toxicity than chemotherapy when studied in progressive disease, subsequent studies focused on PD-1 inhibition in the frontline setting. CheckMate 066 was a phase 3 trial comparing nivolumab to dacarbazine as first-line therapy for 418 patients with untreated metastatic melanoma who did not have a BRAF mutation. For the primary end point of 1-year OS, nivolumab was superior to dacarbazine (72.9% vs 42.1%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.42; P < 0.001). Treatment with nivolumab also resulted in superior ORR (40% vs 14%) and PFS (5.1 months vs 2.2 months). Additionally, nivolumab therapy had a lower rate of grade 3 or 4 toxicity compared to dacarbazine (11.7% vs 17.6%).25

The KEYNOTE-006 trial compared 2 separate dosing schedules of pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks versus every 3 weeks) to ipilimumab (3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 cycles) in a 1:1:1 ratio in 834 patients with metastatic melanoma who had received up to 1 prior systemic therapy, but no prior CTLA-4 or PD-1 inhibitors. The first published data reported statistically significant outcomes for the co-primary end points of 6-month PFS (47.3% for pembrolizumab every 2 weeks vs 46.4% for pembrolizumab every 3 weeks vs 26.5% for ipilimumab; HR, 0.58 for both pembrolizumab groups compared to ipilimumab; P < 0.001) and 12-month OS (74.1% vs 68.4% vs 58.2%) with pembrolizumab compared to ipilimumab. Compared to ipilimumab, pembrolizumab every 2 weeks had a hazard ratio of 0.63 (P = 0.0005) and pembrolizumab every 3 weeks had a hazard ratio of 0.69 (P = 0.0036). The pembrolizumab groups was also had lower rates of grade 3 to 5 toxicity (13.3% vs 10.1% vs 19.9%).5 Updated outcomes demonstrated improved ORR compared to the first analysis (37% vs 36% vs 13%), and improved OS (median OS, not reached for the pembrolizumab groups vs 16.0 months for the ipilimumab group; HR, 0.68, P = 0.0009 for pembrolizumab every 2 weeks versus HR 0.68, P = 0.0008 for pembrolizumab every 3 weeks).26 In addition, 24-month OS was 55% in both pembrolizumab groups compared to 43% in the ipilimumab group. Grade 3 or 4 toxicity occurred less frequently with pembrolizumab (17% vs 17% vs 20%).

Further analysis from the KEYNOTE-006 trial data demonstrated improved ORR, PFS, and OS with pembrolizumab compared to ipilimumab in tumors positive for PD-L1 expression. For PD-L1-negative tumors, response rate was higher, and PFS and OS rates were similar with pembrolizumab compared to ipilimumab. Given that pembrolizumab was associated with similar survival outcomes in PD-L1-negative tumors and with less toxicity than ipilimumab, the superiority of PD-L1 inhibitors over ipilimumab was further supported, regardless of tumor PD-L1 status.27

In sum, PD-1 inhibition should be considered the first-line immunotherapy in advanced melanoma, either alone or in combination with ipilimumab, as discussed in the following section. There is no longer a role for ipilimumab monotherapy in the first-line setting, based on evidence from direct comparison to single-agent PD-1 inhibition in clinical trials that demonstrated superior efficacy and less serious toxicity with PD-1 inhibitors.5,26 The finding that ORR and OS outcomes with single-agent PD-1 inhibitors are higher in treatment-naive patients compared to those receiving prior therapies also supports this approach.22

Combination CTLA-4 and PD-1 Therapy

Despite the potential for durable responses, the majority of patients fail to respond to single-agent PD-1 therapy. Given that preclinical data had suggested the potential for synergy between dual inhibition of CTLA-4 and PD-1, clinical trials were designed to test this approach. The first randomized phase 2 trial that established superior efficacy with combination therapy was the CheckMate 069 trial comparing nivolumab plus ipilimumab to ipilimumab monotherapy. Combination therapy resulted in increased ORR (59% vs 11%), median PFS (not reached vs 3.0 months), 2-year PFS (51.3% vs 12.0%), and 2-year OS (63.8% vs 53.6%).28 Similarly, a phase 1b trial of pembrolizumab plus reduced-dose ipilimumab demonstrated an ORR of 61%, with a 1-year PFS of 69% and 1-year OS of 89%.29

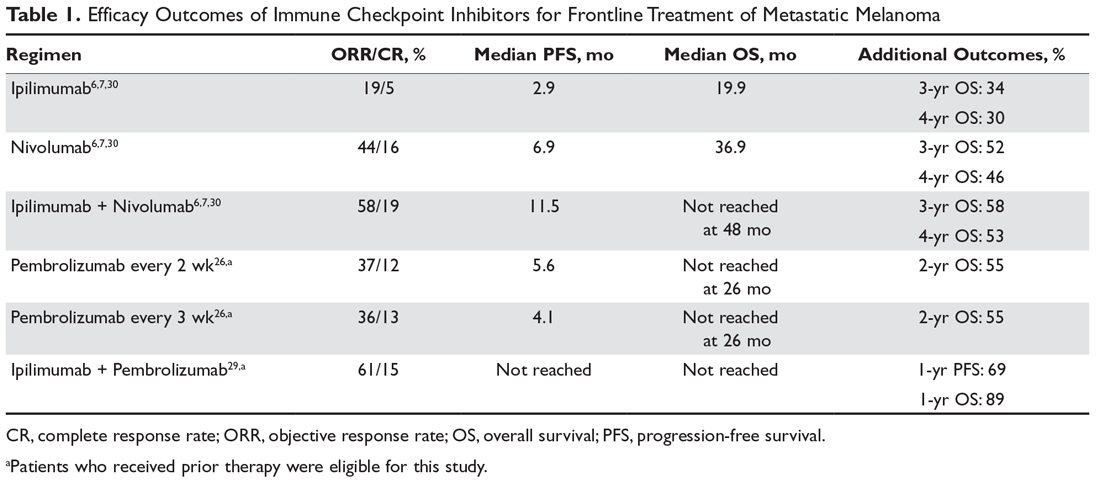

The landmark phase 3 CheckMate 067 trial analyzed efficacy outcomes for 3 different treatment regimens including nivolumab plus ipilimumab, nivolumab monotherapy, and ipilimumab monotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. The trial was powered to compare survival outcomes for both the combination therapy arm against ipilimumab and the nivolumab monotherapy arm against ipilimumab, but not to compare combination therapy to nivolumab monotherapy. The initial analysis demonstrated a median PFS of 11.5 months with combination therapy versus 6.9 months with nivolumab and 2.9 months with ipilimumab, as well as an ORR of 58% versus 44% and 19%, respectively (Table 1).6 The updated 3-year survival outcomes from CheckMate 067 were notable for superior median OS with combination therapy (not reached in combination vs 37.6 months for nivolumab vs 19.9 months ipilimumab), improved 3-year OS (58% vs 52% vs 34%), and improved 3-year PFS (39% vs 32% vs 10%).7 In the reported 4-year survival outcomes, median OS was not reached in the combination therapy group, and was 36.9 months in the nivolumab monotherapy group and 19.9 months in the ipilimumab monotherapy group. Rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events were significantly higher in the combination therapy group, at 59% compared to 22% with nivolumab monotherapy and 28% with ipilimumab alone.30 The 3- and 4-year OS outcomes (58% and 54%, respectively) with combination therapy were the highest seen in any phase 3 trial for treatment of advanced melanoma, supporting its use as the best approved first-line therapy in those who can tolerate the potential toxicity of combination therapy7,30 The conclusions from this landmark trial were that both combination therapy and nivolumab monotherapy resulted in statistically significant improvement in OS compared to ipilimumab.

Toxicity Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

While immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of many solid tumor malignancies, this new class of cancer therapy has brought about a new type of toxicity for clinicians to be aware of, termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As immune checkpoint inhibitors amplify the immune response against malignancy, they also increase the likelihood that autoreactive T-cells persist and proliferate within the circulation. Therefore, these therapies can result in almost any type of autoimmune side effect. The most commonly reported irAEs in large clinical trials studying CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibitors include rash/pruritus, diarrhea/colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies (thyroiditis, hypophysitis, adrenalitis), and pneumonitis. Other more rare toxicities include pancreatitis, autoimmune hematologic toxicities, cardiac toxicity (myocarditis, heart failure), and neurologic toxicities (neuropathies, myasthenia gravis-like syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome). It has been observed that PD-1 inhibitors have a lower incidence of irAEs than CTLA-4 inhibitors, and that the combined use of PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors is associated with a greater incidence of irAEs compared to monotherapy with either agent.31 Toxicities associated with ipilimumab have been noted to be dose dependent.18 Generally, these toxicities are treated with immunosuppression in the form of glucocorticoids and are often reversible.31 There are several published guidelines that include algorithms for the management of irAEs by organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.32

For example, previously untreated patients treated with ipilimumab plus dacarbazine as compared to dacarbazine plus placebo had greater grade 3 or 4 adverse events (56.3% vs 27.5%), and 77.7% of patients experiencing an irAE of any grade.18 In the CheckMate 066 trial comparing frontline nivolumab to dacarbazine, nivolumab had a lower rate of grade 3 or 4 toxicity (11.7% vs 17.6%) and irAEs were relatively infrequent, with diarrhea and elevated alanine aminotransferase level each being the most prominent irAE (affecting 1.0% of patients).25 In the KEYNOTE-006 trial, irAEs seen in more than 1% of patients treated with pembrolizumab included colitis, hepatitis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, whereas those occurring in more than 1% of patients treated with ipilimumab included colitis and hypophysitis. Overall, there were lower rates of grade 3 to 5 toxicity with the 2 pembrolizumab doses compared to ipilimumab (13.3% pembrolizumab every 2 weeks vs 10.1% pembrolizumab every 3 weeks vs 19.9% ipilimumab).5 In the CheckMate 067 trial comparing nivolumab plus ipilimumab, nivolumab monotherapy, and ipilimumab monotherapy, rates of treatment-related adverse events of any grade were higher in the combination group (96% combination vs 86% nivolumab vs 86% ipilimumab), as were rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events (59% vs 21% vs 28%, respectively). The irAE profile was similar to that demonstrated in prior studies: rash/pruritus were the most common, and diarrhea/colitis, elevated aminotransferases, and endocrinopathies were among the more common irAEs.7

Alternative dosing strategies have been investigated in an effort to preserve efficacy and minimize toxicity. A phase 1b trial of pembrolizumab plus reduced-dose ipilimumab demonstrated an ORR of 61%, with a 1-year PFS of 69% and a 1-year OS of 89%. This combination led to 45% of patients having a grade 3 or 4 adverse event, 60% having irAEs of any grade, and only 27% having grade 3 or 4 irAEs.29 The CheckMate 067 trial studied the combination of nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg.6 The CheckMate 511 trial compared different combination dosing strategies (nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg versus nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg) to assess for safety benefit. In the results published in abstract form, the reduced ipilimumab dose (nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg arm) resulted in significantly decreased grade 3 to 5 adverse events (33.9% vs 48.3%) without significant differences in ORR, PFS, or OS.33

The question about the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in patients who discontinue treatment due to irAEs has been raised, as one hypothesis suggests that such toxicities may also indicate that the antitumor immune response has been activated. In a retrospective pooled analysis of phase 2 and 3 trials where patients received combination therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab and discontinued therapy during the induction phase due to irAEs, outcomes did not appear to be inferior. Median PFS was 8.4 months in those who discontinued therapy compared to 10.8 months in those who continued therapy, but this did not reach statistical significance. Median OS had not been reached in either group and ORR was actually higher in those who discontinued due to adverse events (58.3% vs 50.2%). While this retrospective analysis needs to be validated, it does suggest that patients likely derive antitumor benefit from immunotherapy even if they have to discontinue therapy due to irAEs. Of note, patients in this analysis were not trialed on nivolumab monotherapy after receiving immunosuppressive treatment for toxicity related to combination therapy, which has since been deemed a reasonable treatment option.34

Molecularly Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma

As previously mentioned, the MAPK pathway is frequently altered in metastatic melanoma and thus serves as a target for therapy. Mutations in BRAF can cause constitutive activation of the protein’s kinase function, which subsequently phosphorylates/activates MEK in the absence of extracellular growth signals and causes increased cellular proliferation. For the roughly half of patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma who harbor a BRAF V600 mutation, molecularly targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors has emerged as a standard of care treatment option. As such, all patients with advanced disease should be tested for BRAF mutations.

After early phase 1 studies of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib demonstrated successful inhibition of mutated BRAF,35 subsequent studies confirmed the benefit of BRAF targeted therapy. In the phase 3 randomized controlled BRIM-3 trial comparing vemurafenib with dacarbazine for treatment of 675 patients with previously untreated metastatic melanoma positive for a BRAF V600E mutation, the vemurafenib group had superior ORR and 6-month OS during the first analysis.36 In a subsequent analysis, median PFS and median OS were also superior with vemurafenib compared to dacarbazine, as vemurafenib had a median OS of 13.6 months compared to 9.7 months with dacarbazine (HR, 0.70; P = 0.0008).37 Dabrafenib was the next BRAF inhibitor to demonstrate clinical efficacy with superior PFS compared to dacarbazine.38

Despite tumor shrinkage in the majority of patients, the development of resistance to therapy was an issue early on. The development of acquired resistance emerged as a heterogeneous process, though many of the identified resistance mechanisms involved reactivation of the MAPK pathway.39 A phase 3 trial of 322 patients with metastatic melanoma comparing the MEK inhibitor trametinib as monotherapy against chemotherapy demonstrated a modest improvement in both median PFS and OS.40 As a result, subsequent efforts focused on a strategy of concurrent MEK inhibition as a means to overcome resistance to molecularly targeted monotherapy

At least 4 large phase 3 randomized controlled trials of combination therapy with BRAF plus MEK inhibitors showed an improved ORR, PFS, and OS when compared to BRAF inhibition alone. The COMBI-d trial comparing dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib alone was the first to demonstrate the superiority of combined BRAF/MEK inhibition and made combination therapy the current standard of care for patients with metastatic melanoma and a BRAF V600 mutation. In the final analysis of this trial, 3-year PFS was 22% with combination therapy compared to 12% with dabrafenib alone, and 3-year OS was 44% compared to 32%.8,41,42 A second trial with the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib (COMBI-V) also demonstrated superior efficacy when compared to single-agent vemurafenib without increased toxicity.43 Subsequently, the combination of vemurafenib with MEK inhibitor cobimetinib demonstrated superiority compared to vemurafenib alone,44 followed by the newest combination encorafenib (BRAF inhibitor) and binimetinib (MEK inhibitor) proving superior to either vemurafenib or encorafenib alone.45,46

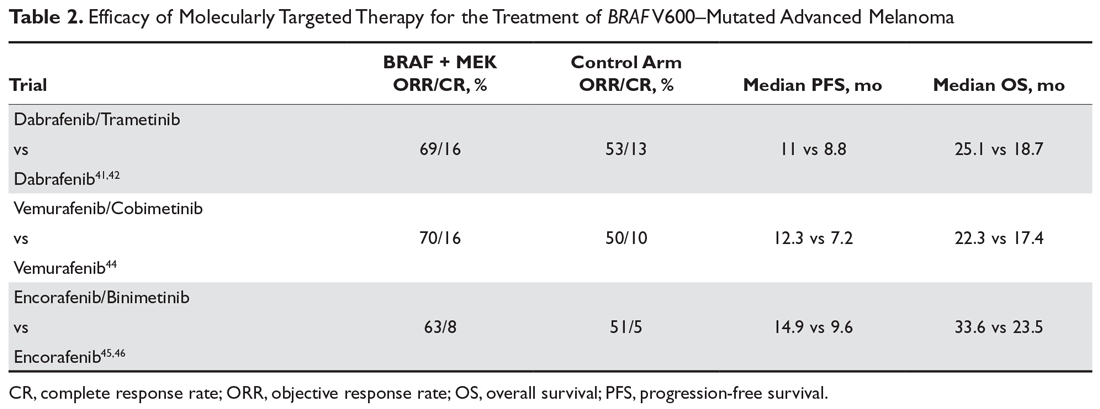

It is important to note that there have been no studies directly comparing the efficacy of the 3 approved BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations, but the 3 different regimens have some differences in their toxicity profiles (Table 2). Of note, single-agent BRAF inhibition was associated with increased cutaneous toxicity, including secondary squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma,47 which was demonstrated to be driven by paradoxical activation of the MAPK pathway.48 The concerning cutaneous toxicities such as squamous cell carcinoma were substantially reduced by combination BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy.47 Collectively, the higher efficacy along with manageable toxicity profile established combination BRAF/MEK inhibition as the preferred regimen for patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma who are being considered for molecularly targeted therapy. BRAF inhibitor monotherapy should only be used when there is a specific concern regarding the use of a MEK inhibitor in certain clinical circumstances.

Other driver mutations associated with metastatic melanoma such as NRAS-mutated tumors have proven more difficult to effectively treat with molecularly targeted therapy, with one study showing that the MEK inhibitor binimetinib resulted in a modest improvement in ORR and median PFS without OS benefit compared to dacarbazine.49 Several phase 2 trials involving metastatic melanoma harboring a c-Kit alteration have demonstrated some efficacy with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib. The largest phase 2 trial of 43 patients treated with imatinib resulted in a 53.5% disease control rate (23.3% partial response and 30.2% stable disease), with 9 of the 10 patients who achieved partial response having a mutation in either exon 11 or 13. Median PFS was 3.5 months and 1-year OS was 51.0%.50

Case Conclusion

Prior to initiation of systemic therapy, the patient’s melanoma is tested and is found to be positive for a BRAF V600K mutation. At his follow-up appointment, the patient continues to endorse generalized weakness, fatigue, issues with balance, and residual pulmonary symptoms after being treated for post-obstructive pneumonia. Given his current symptoms and extent of metastatic disease, immunotherapy is deferred and he is started on combination molecularly targeted therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib. He initially does well, with a partial response noted by resolution of symptoms and decreased size of his intracranial metastases and decreased size of the right lower lobe mass. Further follow-up of this patient is presented in the second article in this 2-part review of advanced melanoma.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7-30.

2. Ives NJ, Stowe RL, Lorigan P, Wheatley K. Chemotherapy compared with biochemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis of 18 trials involving 2621 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5426-34.

3. Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105-16.

4. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711-23.

5. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2522-2532.

6. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonazalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23-34.

7. Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345-1356.

8. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1877-1888.

9. Elwood JM, Jopson J. Melanoma and sun exposure: an overview of published studies. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:198-203.

10. Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, Yaar M. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 199;340:1341-1348.

11. Omholt K, Platz A, Kanter L, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations arise early during melanoma pathogenesis and are preserved throughout tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6483-8.

12. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949-54.

13. Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell 2015;161:1681-96.

14. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

15. Robert C, Ribas A, Hamid O, et al. Durable complete response after discontinuation of pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1668-1674.

16. Salama AKS, Hodi FS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4622-8.

17. Boussiotis VA. Molecular and biochemical aspects of the PD-1 checkpoint pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1767-1778.

18. Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517-2526.

19. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443-2454.

20. Topalian S, Sznol M, McDermott DF, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1020-30.

21. Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375-84.

22. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609.

23. Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:908-18.

24. Hamid O, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Final analysis of a randomised trial comparing pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:37-45.

25. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

26. Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicenter, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006). Lancet Oncol. 2017;390:1853-1862.

27. Carlino MS, Long GV, Schadendorf D, et al. Outcomes by line of therapy and programmed death ligand 1 expression in patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab or ipilimumab in KEYNOTE-006. A randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:236-243.

28. Hodi FS, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1558-1568.

29. Long GV, Atkinson V, Cebon JS, et al. Standard-dose pembrolizumab in combination with reduced-dose ipilimumab for patients with advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-029): an open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1202-10.

30. Hodi FS, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1480-1492.

31. Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1346-1353.

32. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immunotherapy-related toxicities (version 2.2019). www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/immunotherapy.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2019.

33. Lebbé C, Meyer N, Mortier L, et al. Initial results from a phase IIIb/IV study evaluating two dosing regimens of nivolumab (NIVO) in combination with ipilimumab (IPI) in patients with advanced melanoma (CheckMate 511) [Abstract LBA47]. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:mdy424.057.

34. Schadendorf D, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, et al. Efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma who discontinued treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab because of adverse events: a pooled analysis of randomized phase ii and iii trials. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3807-3814.

35. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809-819.

36. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

37. McArthur GA, Chapman PB, Robert C, et al. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAFV600E and BRAFV600K mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:323-332.

38. Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicenter, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;380:358-365.

39. Rizos H, Menzies AM, Pupo GM, et al. BRAF inhibitor resistance mechanisms in metastatic melanoma: spectrum and clinical impact. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1965-1977.

40. Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

41. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicenter, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;386:444-451.

42. Long GV, Flaherty KT, Stroyakovskiy D, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib monotherapy in patients with metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant melanoma: long-term survival and safety analysis of a phase 3 study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1631-1639.

43. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30-39.

44. Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAFV600-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1248-260.

45. Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicenter, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:603-615.

46. Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, et al. Overall survival in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma receiving encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib (COLUMBUS): a multicenter, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1315-1327.

47. Carlos G, Anforth R, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous toxic effects of BRAF inhibitors alone and in combination with MEK inhibitors for metastatic melanoma. JAMA. Dermatol 2015;151:1103-1109.

48. Su F, Viros A, Milagre C, et al. RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:207-215.

49. Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Ascierto P, et al. Binimetinib versus dacarbazine in patients with advanced NRAS-mutant melanoma (NEMO): a multicenter, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:435-445.

50. Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2904-2909.

Malignant melanoma is the most serious form of primary skin cancer and one of the only malignancies in which the incidence rate has been rising. It is estimated that in 2018 there were 91,270 newly diagnosed cases and 9320 deaths from advanced melanoma in the United States. Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer type in males and the sixth most common in females. Despite rising incidence rates, improvement in the treatment of advanced melanoma has resulted in declining death rates over the past decade.1 Although most melanoma is diagnosed at an early stage and can be cured with surgical excision, the prognosis for metastatic melanoma had been historically poor prior to recent advancements in treatment. Conventional chemotherapy treatment with dacarbazine or temozolomide resulted in response rates ranging from 7.5% to 12.1%, but without much impact on median overall survival (OS), with reported OS ranging from 6.4 to 7.8 months. Combination approaches with interferon alfa-2B and low-dose interleukin-2 resulted in improved response rates compared with traditional chemotherapy, but again without survival benefit.2

Immunotherapy in the form of high-dose interleukin-2 emerged as the first therapy to alter the natural history of advanced melanoma, with both improved response rates (objective response rate [ORR], 16%) and median OS (2 months), with some patients achieving durable responses lasting more than 30 months. However, significant systemic toxicity limited its application to carefully selected patients.3 The past decade has brought rapid advancements in treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors and molecularly targeted agents, which have significantly improved ORRs, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS for patients with metastatic melanoma.4-8

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the treatment and sequencing of therapies in advanced melanoma. Here, we review the selection of first-line therapy for metastatic melanoma. Current evidence for immune checkpoint blockade and molecularly targeted agents in the treatment of metastatic melanoma after progression on first-line therapy is discussed in a separate article.

Pathogenesis

The incidence of melanoma is strongly associated with ultraviolet light–mediated DNA damage related to sun exposure. Specifically, melanoma is associated to a greater degree with intense intermittent sun exposure and sunburn, but not associated with higher occupational exposure.9 Ultraviolet radiation can induce DNA damage by a number of mechanisms, and deficient DNA repair leads to somatic mutations that drive the progression from normal melanocyte to melanoma.10

The most commonly identified genetic mutations in cutaneous melanomas are alterations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Typically, an extracellular growth factor causes dimerization of the growth factor receptor, which activates the intracellular RAS GTPase protein. Subsequently BRAF is phosphorylated within the kinase domain, which leads to downstream activation of the MEK and ERK kinases through phosphorylation. Activated ERK leads to phosphorylation of various cytoplasmic and nuclear targets, and the downstream effects of these changes promote cellular proliferation. While activation of this pathway usually requires phosphorylation of BRAF by RAS, mutations placing an acidic amino acid near the kinase domain mimics phosphorylation and leads to constitutive activation of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase in the absence of upstream signaling from extracellular growth factors mediated through RAS.11 One study of tumor samples of 71 patients with cutaneous melanoma detected NRAS mutations in 30% and BRAF mutations in 59% of all tumors tested. Of the BRAF mutation–positive tumors, 88% harbored the Val599Glu mutation, now commonly referred to as the BRAF V600E mutation. The same study demonstrated that the vast majority of BRAF mutations were seen in the primary tumor and were preserved when metastases were analyzed. Additionally, both NRAS and BRAF mutations were detected in the radial growth phase of the melanoma tumor. These findings indicate that alterations in the MAPK pathway occur early in the pathogenesis of advanced melanoma.11 Another group demonstrated that 66% of malignant melanoma tumor samples harbored BRAF mutations, of which 80% were specifically the V600E mutation. In vitro assays showed that the BRAF V600E–mutated kinase had greater than 10-fold kinase activity compared to wild-type BRAF, and that this kinase enhanced cellular proliferation even when upstream NRAS signaling was inhibited.12

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network performed a large analysis of tumor samples from 331 different melanoma patients and studied variations at the DNA, RNA, and protein levels. The study established a framework of 4 notable genomic subtypes, including mutant BRAF (52%), mutant RAS (28%), mutant NF1 (14%), and triple wild-type (6%). Additionally, mRNA transcriptomic analysis of overexpressed genes identified 3 different subclasses, which were labeled as “immune,” “keratin,” and “MITF-low.” The immune subclass was characterized by increased expression of proteins found in immune cells, immune signaling molecules, immune checkpoint proteins, cytokines, and chemokines, and correlated with increased lymphocyte invasion within the tumor. Interestingly, in the post-accession survival analysis, the “immune” transcriptomic subclass was statistically correlated with an improved prognosis.13 Having an understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of advanced melanoma helps to create a framework for understanding the mechanisms of current standard of care therapies for the disease.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old Caucasian man with a history of well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension is being followed by his dermatologist for surveillance of melanocytic nevi. On follow-up he is noted to have an asymmetrical melanocytic lesion over the right scalp with irregular borders and variegated color. He is asymptomatic and the remainder of physical examination is unremarkable, as he has no other concerning skin lesions and no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

How is melanoma diagnosed?

Detailed discussion about diagnosis and staging will be deferred in this review of treatment of advanced melanoma. In brief, melanoma is best diagnosed by excisional biopsy and histopathology. Staging of melanoma is done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition, using a TNM staging system that incorporates tumor thickness (Breslow depth); ulceration; number of involved regional lymph nodes; presence of in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases; distant metastases; and serum lactate dehydrogenase level.14

Case Continued

The patient undergoes a wide excisional biopsy of the right scalp lesion, which is consistent with malignant melanoma. Pathology demonstrates a Breslow depth of 2.6 mm, 2 mitotic figures/mm2, and no evidence of ulceration. He subsequently undergoes wide local excision with 0/3 sentinel lymph nodes positive for malignancy. His final staging is consistent with pT3aN0M0, stage IIA melanoma.

He is seen in follow-up with medical oncology for the next 3.5 years without any evidence of disease recurrence. He then develops symptoms of vertigo, diplopia, and recurrent falls, prompting medical attention. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain reveals multiple supratentorial and infratentorial lesions concerning for intracranial metastases. Further imaging with computed tomography (CT) chest/abdomen/pelvis reveals a right lower lobe pulmonary mass with right hilar and subcarinal lymphadenopathy. He is admitted for treatment with intravenous dexamethasone and further evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the right lower lobe mass, which reveals metastatic melanoma. Given the extent of his intracranial metastases, he is treated with whole brain radiation therapy for symptomatic relief prior to initiating systemic therapy.

What is the general approach to first-line treatment for metastatic melanoma?

The past decade has brought an abundance of data supporting the use of immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors or molecularly targeted therapy with combined BRAF/MEK inhibitors in the first-line setting.4-8 After the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma has been made, molecular testing is recommended to determine the BRAF status of the tumor. Immunotherapy is the clear choice for first-line therapy in the absence of an activating BRAF V600 mutation. When a BRAF V600 mutation is present, current evidence supports the use of either immunotherapy or molecularly targeted therapy as first-line therapy.

To date, there have been no prospective clinical trials comparing the sequencing of immunotherapy and molecularly targeted therapy in the first-line setting. An ongoing clinical trial (NCT02224781) is comparing dabrafenib and trametinib followed by ipilimumab and nivolumab at time of progression to ipilimumab and nivolumab followed by dabrafenib and trametinib in patients with newly diagnosed stage III/IV BRAF V600 mutation–positive melanoma. The primary outcome measure is 2-year OS. Until completion of that trial, current practice regarding which type of therapy to use in the first-line setting is based on a number of factors including clinical characteristics and provider preferences.

Data suggest that immunotherapies can produce durable responses, especially after treatment completion or discontinuation, albeit at the expense of taking a longer time to achieve clinical benefit and the risk of potentially serious immune-related adverse effects. This idea of a durable, off-treatment response is highlighted by a study that followed 105 patients who had achieved a complete response (CR) and found that 24-month disease-free survival from the time of CR was 90.9% in all patients and 89.9% in the 67 patients who had discontinued pembrolizumab after attaining CR.15 BRAF/MEK inhibition has the potential for rapid clinical responses, though concerns exist about the development of resistance to therapy. The following sections explore the evidence supporting the use of these therapies.

Immunotherapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Immunotherapy via immune checkpoint blockade has revolutionized the treatment of many solid tumors over the past decade. The promise of immunotherapy revolves around the potential for achieving a dynamic and durable systemic response against cancer by augmenting the antitumor effects of the immune system. T-cells are central to mounting a systemic antitumor response, and, in addition to antigen recognition, their function depends heavily on fine tuning between co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signaling. The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) expressed on T-cells was the first discovered co-inhibitory receptor of T-cell activation.16 Later, it was discovered that the programmed cell death 1 receptor (PD-1), expressed on T-cells, and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, expressed on antigen presenting cells, tumor cells, or other cells in the tumor microenvironment, also served as a potent negative regulator of T-cell function.17

Together, these 2 signaling pathways help to maintain peripheral immune tolerance, whereby autoreactive T-cells that have escaped from the thymus are silenced to prevent autoimmunity. However, these pathways can also be utilized by cancer cells to escape immune surveillance. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the aforementioned co-inhibitory signaling pathways, and thus augment the immune response, have proven to be an effective anticancer therapy capable of producing profound and durable responses in certain malignancies.16,17

Ipilimumab

Ipilimumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the function of the CTLA-4 co-inhibitory immune checkpoint. In a phase 3 randomized controlled trial of 676 patients with previously treated metastatic melanoma, ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 cycles, with or without a gp100 peptide vaccine, resulted in an improved median OS of 10.0 and 10.1 months, respectively, compared to 6.4 months in those receiving the peptide vaccine alone, meeting the primary endpoint.4 Subsequently, a phase 3 trial of 502 patients with untreated metastatic melanoma compared ipilimumab at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 cycles plus dacarbazine to dacarbazine plus placebo and found a significant increase in median OS (11.2 months vs 9.1 months), with no additive benefit of chemotherapy. There was a higher reported rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events in this trial with ipilimumab dosed at 10 mg/kg, which was felt to be dose-related.18 These trials were the first to show improved OS with any systemic therapy in metastatic melanoma and led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ipilimumab for this indication in 2011.

PD-1 Inhibitor Monotherapy

The PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab were initially approved for metastatic melanoma after progression on ipilimumab. In the phase 1 trial of patients with previously treated metastatic melanoma, nivolumab therapy resulted in an ORR of 28%.19 The subsequent phase 2 trial conducted in pretreated patients, including patients who had progressed on ipilimumab, confirmed a similar ORR of 31%, as well as a median PFS of 3.7 months and a median OS of 16.8 months. The estimated response duration in patients who did achieve a response to therapy was 2 years.20 A phase 3 trial (CheckMate 037) comparing nivolumab (n = 120) to investigator’s choice chemotherapy (n = 47) in those with melanoma refractory to ipilimumab demonstrated that nivolumab was superior for the primary endpoint of ORR (31.7% vs 10.6%), had less toxicity (5% rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events versus 9%), and increased median duration of response (32 months vs 13 months).21

The phase 1 trial (KEYNOTE-001) testing the efficacy of pembrolizumab demonstrated an ORR of 33% in the total population of patients treated and an ORR of 45% in those who were treatment-naive. Additionally, the median OS was 23 months for the total population and 31 months for treatment-naive patients, with only 14% of patients experiencing a grade 3 or 4 adverse event.22 The KEYNOTE-002 phase 2 trial compared 2 different pembrolizumab doses (2 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks) to investigator’s choice chemotherapy (paclitaxel plus carboplatin, paclitaxel, carboplatin, dacarbazine, or oral temozolomide) in 540 patients with advanced melanoma with documented progression on ipilimumab with or without prior progression on molecularly targeted therapy if positive for a BRAF V600 mutation. The final analysis demonstrated significantly improved ORR with pembrolizumab (22% at 2 mg/kg vs 26% at 10 mg/kg vs 4% chemotherapy) and significantly improved 24-month PFS (16% vs 22% vs 0.6%, respectively). There was a nonstatistically significant improvement in median OS (13.4 months vs 14.7 months vs 10 months), although 55% of the patients initially assigned to the chemotherapy arm crossed over and received pembrolizumab after documentation of progressive disease.23,24

Because PD-1 inhibition improved efficacy with less toxicity than chemotherapy when studied in progressive disease, subsequent studies focused on PD-1 inhibition in the frontline setting. CheckMate 066 was a phase 3 trial comparing nivolumab to dacarbazine as first-line therapy for 418 patients with untreated metastatic melanoma who did not have a BRAF mutation. For the primary end point of 1-year OS, nivolumab was superior to dacarbazine (72.9% vs 42.1%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.42; P < 0.001). Treatment with nivolumab also resulted in superior ORR (40% vs 14%) and PFS (5.1 months vs 2.2 months). Additionally, nivolumab therapy had a lower rate of grade 3 or 4 toxicity compared to dacarbazine (11.7% vs 17.6%).25

The KEYNOTE-006 trial compared 2 separate dosing schedules of pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks versus every 3 weeks) to ipilimumab (3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 cycles) in a 1:1:1 ratio in 834 patients with metastatic melanoma who had received up to 1 prior systemic therapy, but no prior CTLA-4 or PD-1 inhibitors. The first published data reported statistically significant outcomes for the co-primary end points of 6-month PFS (47.3% for pembrolizumab every 2 weeks vs 46.4% for pembrolizumab every 3 weeks vs 26.5% for ipilimumab; HR, 0.58 for both pembrolizumab groups compared to ipilimumab; P < 0.001) and 12-month OS (74.1% vs 68.4% vs 58.2%) with pembrolizumab compared to ipilimumab. Compared to ipilimumab, pembrolizumab every 2 weeks had a hazard ratio of 0.63 (P = 0.0005) and pembrolizumab every 3 weeks had a hazard ratio of 0.69 (P = 0.0036). The pembrolizumab groups was also had lower rates of grade 3 to 5 toxicity (13.3% vs 10.1% vs 19.9%).5 Updated outcomes demonstrated improved ORR compared to the first analysis (37% vs 36% vs 13%), and improved OS (median OS, not reached for the pembrolizumab groups vs 16.0 months for the ipilimumab group; HR, 0.68, P = 0.0009 for pembrolizumab every 2 weeks versus HR 0.68, P = 0.0008 for pembrolizumab every 3 weeks).26 In addition, 24-month OS was 55% in both pembrolizumab groups compared to 43% in the ipilimumab group. Grade 3 or 4 toxicity occurred less frequently with pembrolizumab (17% vs 17% vs 20%).

Further analysis from the KEYNOTE-006 trial data demonstrated improved ORR, PFS, and OS with pembrolizumab compared to ipilimumab in tumors positive for PD-L1 expression. For PD-L1-negative tumors, response rate was higher, and PFS and OS rates were similar with pembrolizumab compared to ipilimumab. Given that pembrolizumab was associated with similar survival outcomes in PD-L1-negative tumors and with less toxicity than ipilimumab, the superiority of PD-L1 inhibitors over ipilimumab was further supported, regardless of tumor PD-L1 status.27

In sum, PD-1 inhibition should be considered the first-line immunotherapy in advanced melanoma, either alone or in combination with ipilimumab, as discussed in the following section. There is no longer a role for ipilimumab monotherapy in the first-line setting, based on evidence from direct comparison to single-agent PD-1 inhibition in clinical trials that demonstrated superior efficacy and less serious toxicity with PD-1 inhibitors.5,26 The finding that ORR and OS outcomes with single-agent PD-1 inhibitors are higher in treatment-naive patients compared to those receiving prior therapies also supports this approach.22

Combination CTLA-4 and PD-1 Therapy

Despite the potential for durable responses, the majority of patients fail to respond to single-agent PD-1 therapy. Given that preclinical data had suggested the potential for synergy between dual inhibition of CTLA-4 and PD-1, clinical trials were designed to test this approach. The first randomized phase 2 trial that established superior efficacy with combination therapy was the CheckMate 069 trial comparing nivolumab plus ipilimumab to ipilimumab monotherapy. Combination therapy resulted in increased ORR (59% vs 11%), median PFS (not reached vs 3.0 months), 2-year PFS (51.3% vs 12.0%), and 2-year OS (63.8% vs 53.6%).28 Similarly, a phase 1b trial of pembrolizumab plus reduced-dose ipilimumab demonstrated an ORR of 61%, with a 1-year PFS of 69% and 1-year OS of 89%.29

The landmark phase 3 CheckMate 067 trial analyzed efficacy outcomes for 3 different treatment regimens including nivolumab plus ipilimumab, nivolumab monotherapy, and ipilimumab monotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. The trial was powered to compare survival outcomes for both the combination therapy arm against ipilimumab and the nivolumab monotherapy arm against ipilimumab, but not to compare combination therapy to nivolumab monotherapy. The initial analysis demonstrated a median PFS of 11.5 months with combination therapy versus 6.9 months with nivolumab and 2.9 months with ipilimumab, as well as an ORR of 58% versus 44% and 19%, respectively (Table 1).6 The updated 3-year survival outcomes from CheckMate 067 were notable for superior median OS with combination therapy (not reached in combination vs 37.6 months for nivolumab vs 19.9 months ipilimumab), improved 3-year OS (58% vs 52% vs 34%), and improved 3-year PFS (39% vs 32% vs 10%).7 In the reported 4-year survival outcomes, median OS was not reached in the combination therapy group, and was 36.9 months in the nivolumab monotherapy group and 19.9 months in the ipilimumab monotherapy group. Rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events were significantly higher in the combination therapy group, at 59% compared to 22% with nivolumab monotherapy and 28% with ipilimumab alone.30 The 3- and 4-year OS outcomes (58% and 54%, respectively) with combination therapy were the highest seen in any phase 3 trial for treatment of advanced melanoma, supporting its use as the best approved first-line therapy in those who can tolerate the potential toxicity of combination therapy7,30 The conclusions from this landmark trial were that both combination therapy and nivolumab monotherapy resulted in statistically significant improvement in OS compared to ipilimumab.

Toxicity Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

While immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of many solid tumor malignancies, this new class of cancer therapy has brought about a new type of toxicity for clinicians to be aware of, termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As immune checkpoint inhibitors amplify the immune response against malignancy, they also increase the likelihood that autoreactive T-cells persist and proliferate within the circulation. Therefore, these therapies can result in almost any type of autoimmune side effect. The most commonly reported irAEs in large clinical trials studying CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibitors include rash/pruritus, diarrhea/colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies (thyroiditis, hypophysitis, adrenalitis), and pneumonitis. Other more rare toxicities include pancreatitis, autoimmune hematologic toxicities, cardiac toxicity (myocarditis, heart failure), and neurologic toxicities (neuropathies, myasthenia gravis-like syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome). It has been observed that PD-1 inhibitors have a lower incidence of irAEs than CTLA-4 inhibitors, and that the combined use of PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors is associated with a greater incidence of irAEs compared to monotherapy with either agent.31 Toxicities associated with ipilimumab have been noted to be dose dependent.18 Generally, these toxicities are treated with immunosuppression in the form of glucocorticoids and are often reversible.31 There are several published guidelines that include algorithms for the management of irAEs by organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.32

For example, previously untreated patients treated with ipilimumab plus dacarbazine as compared to dacarbazine plus placebo had greater grade 3 or 4 adverse events (56.3% vs 27.5%), and 77.7% of patients experiencing an irAE of any grade.18 In the CheckMate 066 trial comparing frontline nivolumab to dacarbazine, nivolumab had a lower rate of grade 3 or 4 toxicity (11.7% vs 17.6%) and irAEs were relatively infrequent, with diarrhea and elevated alanine aminotransferase level each being the most prominent irAE (affecting 1.0% of patients).25 In the KEYNOTE-006 trial, irAEs seen in more than 1% of patients treated with pembrolizumab included colitis, hepatitis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, whereas those occurring in more than 1% of patients treated with ipilimumab included colitis and hypophysitis. Overall, there were lower rates of grade 3 to 5 toxicity with the 2 pembrolizumab doses compared to ipilimumab (13.3% pembrolizumab every 2 weeks vs 10.1% pembrolizumab every 3 weeks vs 19.9% ipilimumab).5 In the CheckMate 067 trial comparing nivolumab plus ipilimumab, nivolumab monotherapy, and ipilimumab monotherapy, rates of treatment-related adverse events of any grade were higher in the combination group (96% combination vs 86% nivolumab vs 86% ipilimumab), as were rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events (59% vs 21% vs 28%, respectively). The irAE profile was similar to that demonstrated in prior studies: rash/pruritus were the most common, and diarrhea/colitis, elevated aminotransferases, and endocrinopathies were among the more common irAEs.7

Alternative dosing strategies have been investigated in an effort to preserve efficacy and minimize toxicity. A phase 1b trial of pembrolizumab plus reduced-dose ipilimumab demonstrated an ORR of 61%, with a 1-year PFS of 69% and a 1-year OS of 89%. This combination led to 45% of patients having a grade 3 or 4 adverse event, 60% having irAEs of any grade, and only 27% having grade 3 or 4 irAEs.29 The CheckMate 067 trial studied the combination of nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg.6 The CheckMate 511 trial compared different combination dosing strategies (nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg versus nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg) to assess for safety benefit. In the results published in abstract form, the reduced ipilimumab dose (nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg arm) resulted in significantly decreased grade 3 to 5 adverse events (33.9% vs 48.3%) without significant differences in ORR, PFS, or OS.33

The question about the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in patients who discontinue treatment due to irAEs has been raised, as one hypothesis suggests that such toxicities may also indicate that the antitumor immune response has been activated. In a retrospective pooled analysis of phase 2 and 3 trials where patients received combination therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab and discontinued therapy during the induction phase due to irAEs, outcomes did not appear to be inferior. Median PFS was 8.4 months in those who discontinued therapy compared to 10.8 months in those who continued therapy, but this did not reach statistical significance. Median OS had not been reached in either group and ORR was actually higher in those who discontinued due to adverse events (58.3% vs 50.2%). While this retrospective analysis needs to be validated, it does suggest that patients likely derive antitumor benefit from immunotherapy even if they have to discontinue therapy due to irAEs. Of note, patients in this analysis were not trialed on nivolumab monotherapy after receiving immunosuppressive treatment for toxicity related to combination therapy, which has since been deemed a reasonable treatment option.34

Molecularly Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma

As previously mentioned, the MAPK pathway is frequently altered in metastatic melanoma and thus serves as a target for therapy. Mutations in BRAF can cause constitutive activation of the protein’s kinase function, which subsequently phosphorylates/activates MEK in the absence of extracellular growth signals and causes increased cellular proliferation. For the roughly half of patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma who harbor a BRAF V600 mutation, molecularly targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors has emerged as a standard of care treatment option. As such, all patients with advanced disease should be tested for BRAF mutations.

After early phase 1 studies of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib demonstrated successful inhibition of mutated BRAF,35 subsequent studies confirmed the benefit of BRAF targeted therapy. In the phase 3 randomized controlled BRIM-3 trial comparing vemurafenib with dacarbazine for treatment of 675 patients with previously untreated metastatic melanoma positive for a BRAF V600E mutation, the vemurafenib group had superior ORR and 6-month OS during the first analysis.36 In a subsequent analysis, median PFS and median OS were also superior with vemurafenib compared to dacarbazine, as vemurafenib had a median OS of 13.6 months compared to 9.7 months with dacarbazine (HR, 0.70; P = 0.0008).37 Dabrafenib was the next BRAF inhibitor to demonstrate clinical efficacy with superior PFS compared to dacarbazine.38

Despite tumor shrinkage in the majority of patients, the development of resistance to therapy was an issue early on. The development of acquired resistance emerged as a heterogeneous process, though many of the identified resistance mechanisms involved reactivation of the MAPK pathway.39 A phase 3 trial of 322 patients with metastatic melanoma comparing the MEK inhibitor trametinib as monotherapy against chemotherapy demonstrated a modest improvement in both median PFS and OS.40 As a result, subsequent efforts focused on a strategy of concurrent MEK inhibition as a means to overcome resistance to molecularly targeted monotherapy

At least 4 large phase 3 randomized controlled trials of combination therapy with BRAF plus MEK inhibitors showed an improved ORR, PFS, and OS when compared to BRAF inhibition alone. The COMBI-d trial comparing dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib alone was the first to demonstrate the superiority of combined BRAF/MEK inhibition and made combination therapy the current standard of care for patients with metastatic melanoma and a BRAF V600 mutation. In the final analysis of this trial, 3-year PFS was 22% with combination therapy compared to 12% with dabrafenib alone, and 3-year OS was 44% compared to 32%.8,41,42 A second trial with the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib (COMBI-V) also demonstrated superior efficacy when compared to single-agent vemurafenib without increased toxicity.43 Subsequently, the combination of vemurafenib with MEK inhibitor cobimetinib demonstrated superiority compared to vemurafenib alone,44 followed by the newest combination encorafenib (BRAF inhibitor) and binimetinib (MEK inhibitor) proving superior to either vemurafenib or encorafenib alone.45,46

It is important to note that there have been no studies directly comparing the efficacy of the 3 approved BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations, but the 3 different regimens have some differences in their toxicity profiles (Table 2). Of note, single-agent BRAF inhibition was associated with increased cutaneous toxicity, including secondary squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma,47 which was demonstrated to be driven by paradoxical activation of the MAPK pathway.48 The concerning cutaneous toxicities such as squamous cell carcinoma were substantially reduced by combination BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy.47 Collectively, the higher efficacy along with manageable toxicity profile established combination BRAF/MEK inhibition as the preferred regimen for patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma who are being considered for molecularly targeted therapy. BRAF inhibitor monotherapy should only be used when there is a specific concern regarding the use of a MEK inhibitor in certain clinical circumstances.

Other driver mutations associated with metastatic melanoma such as NRAS-mutated tumors have proven more difficult to effectively treat with molecularly targeted therapy, with one study showing that the MEK inhibitor binimetinib resulted in a modest improvement in ORR and median PFS without OS benefit compared to dacarbazine.49 Several phase 2 trials involving metastatic melanoma harboring a c-Kit alteration have demonstrated some efficacy with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib. The largest phase 2 trial of 43 patients treated with imatinib resulted in a 53.5% disease control rate (23.3% partial response and 30.2% stable disease), with 9 of the 10 patients who achieved partial response having a mutation in either exon 11 or 13. Median PFS was 3.5 months and 1-year OS was 51.0%.50

Case Conclusion

Prior to initiation of systemic therapy, the patient’s melanoma is tested and is found to be positive for a BRAF V600K mutation. At his follow-up appointment, the patient continues to endorse generalized weakness, fatigue, issues with balance, and residual pulmonary symptoms after being treated for post-obstructive pneumonia. Given his current symptoms and extent of metastatic disease, immunotherapy is deferred and he is started on combination molecularly targeted therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib. He initially does well, with a partial response noted by resolution of symptoms and decreased size of his intracranial metastases and decreased size of the right lower lobe mass. Further follow-up of this patient is presented in the second article in this 2-part review of advanced melanoma.

Malignant melanoma is the most serious form of primary skin cancer and one of the only malignancies in which the incidence rate has been rising. It is estimated that in 2018 there were 91,270 newly diagnosed cases and 9320 deaths from advanced melanoma in the United States. Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer type in males and the sixth most common in females. Despite rising incidence rates, improvement in the treatment of advanced melanoma has resulted in declining death rates over the past decade.1 Although most melanoma is diagnosed at an early stage and can be cured with surgical excision, the prognosis for metastatic melanoma had been historically poor prior to recent advancements in treatment. Conventional chemotherapy treatment with dacarbazine or temozolomide resulted in response rates ranging from 7.5% to 12.1%, but without much impact on median overall survival (OS), with reported OS ranging from 6.4 to 7.8 months. Combination approaches with interferon alfa-2B and low-dose interleukin-2 resulted in improved response rates compared with traditional chemotherapy, but again without survival benefit.2

Immunotherapy in the form of high-dose interleukin-2 emerged as the first therapy to alter the natural history of advanced melanoma, with both improved response rates (objective response rate [ORR], 16%) and median OS (2 months), with some patients achieving durable responses lasting more than 30 months. However, significant systemic toxicity limited its application to carefully selected patients.3 The past decade has brought rapid advancements in treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors and molecularly targeted agents, which have significantly improved ORRs, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS for patients with metastatic melanoma.4-8

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the treatment and sequencing of therapies in advanced melanoma. Here, we review the selection of first-line therapy for metastatic melanoma. Current evidence for immune checkpoint blockade and molecularly targeted agents in the treatment of metastatic melanoma after progression on first-line therapy is discussed in a separate article.

Pathogenesis

The incidence of melanoma is strongly associated with ultraviolet light–mediated DNA damage related to sun exposure. Specifically, melanoma is associated to a greater degree with intense intermittent sun exposure and sunburn, but not associated with higher occupational exposure.9 Ultraviolet radiation can induce DNA damage by a number of mechanisms, and deficient DNA repair leads to somatic mutations that drive the progression from normal melanocyte to melanoma.10

The most commonly identified genetic mutations in cutaneous melanomas are alterations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Typically, an extracellular growth factor causes dimerization of the growth factor receptor, which activates the intracellular RAS GTPase protein. Subsequently BRAF is phosphorylated within the kinase domain, which leads to downstream activation of the MEK and ERK kinases through phosphorylation. Activated ERK leads to phosphorylation of various cytoplasmic and nuclear targets, and the downstream effects of these changes promote cellular proliferation. While activation of this pathway usually requires phosphorylation of BRAF by RAS, mutations placing an acidic amino acid near the kinase domain mimics phosphorylation and leads to constitutive activation of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase in the absence of upstream signaling from extracellular growth factors mediated through RAS.11 One study of tumor samples of 71 patients with cutaneous melanoma detected NRAS mutations in 30% and BRAF mutations in 59% of all tumors tested. Of the BRAF mutation–positive tumors, 88% harbored the Val599Glu mutation, now commonly referred to as the BRAF V600E mutation. The same study demonstrated that the vast majority of BRAF mutations were seen in the primary tumor and were preserved when metastases were analyzed. Additionally, both NRAS and BRAF mutations were detected in the radial growth phase of the melanoma tumor. These findings indicate that alterations in the MAPK pathway occur early in the pathogenesis of advanced melanoma.11 Another group demonstrated that 66% of malignant melanoma tumor samples harbored BRAF mutations, of which 80% were specifically the V600E mutation. In vitro assays showed that the BRAF V600E–mutated kinase had greater than 10-fold kinase activity compared to wild-type BRAF, and that this kinase enhanced cellular proliferation even when upstream NRAS signaling was inhibited.12