User login

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the first article in that effort.

Over the past two decades Afghanistan became known to many for its invasion by the Soviets (the war the mujahideen fought against its occupiers), the bloody infighting that followed the Soviet withdrawal, and the horrific rule of the Taliban. The expulsion of the Taliban in 2001 by coalition forces and Afghanistan’s recent steps toward democracy have made it the focus of much world attention.

Afghanistan’s health situation is among the worst in the world.1 The data that emerged in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban reported a maternal mortality ratio of 1,600 per 100,000 women, which translates into a lifetime risk that one in six women will die of complications of pregnancy and delivery.2-3 The same study showed severe inequities in mortality rates between rural and urban areas: Kabul’s maternal mortality ratio is 400 per 100,000, whereas in rural Badakhshan province it is 6,500 per 100,000—the highest recorded rate in the world in modern times.2 Afghanistan is the only country in the world where men outlive women. Twenty-five percent of children die before age five—most of treatable diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and preventable diseases such as measles and pertussis. Children, women, and men face risks from communicable diseases that are among the highest in the world, as well as the risk of death or serious injury from landmines and other unexploded ordnance.

In this setting, the Ministry of Public Health made two major decisions in 2002: All health services would be contracted to nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry would be the steward of the health system, setting policies and regulating services; and the Basic Package of Health Services would be the main policy that all service providers would follow.4-5 This package defines specific services focused on women’s and children’s needs by level and by appropriate intervention.6 The Basic Package also stresses equity by giving priority to rural over urban areas and to women’s participation over men’s. A related policy on hospitals limits spending on hospitals to 40% of the national health budget, with the remaining 60% to be spent on basic health services.7

State of Hospitals

Many health facilities—especially hospitals—had been damaged or destroyed. A survey of all health facilities in the country by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in 2002, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other donors, found that 35% of the facilities were severely damaged due to war or natural disasters, and the rest failed to meet current World Health Organization standards.8 A second major concern was the lack of health professionals, many of whom had fled the country during the war years. Finally, the staff remaining, especially physicians, lacked good clinical training and continuing education, which compromised quality of care. The Rural Expansion of Afghanistan’s Community-based Healthcare (REACH) was designed to address all these issues. REACH is a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by MSH and the Afghan Ministry of Public Health. Partners include the Academy for Educational Development; JHPIEGO (an international health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University); Technical Assistance, Inc., and the University of Massachusetts/Amherst.

Hospitals are a critical element of the Afghan health system because they are part of the referral system that plays an essential role in reducing high maternal and early childhood mortality rates. In addition, hospitals use many of the most skilled health workers and the financial resources of the health system. Dramatic improvements in hospital management are needed so hospitals can use these scarce resources effectively and efficiently.9

Challenges

In brief, the key issues facing hospitals in the Afghan health system are:

- Maldistribution of hospitals and hospital beds throughout the country, which means a lack of equitable access to hospital care. People in urban areas have access but semi-urban and rural populations have limited access. For example, Kabul has 1.28 beds per 1,000 people while the provinces have only .22 per 1,000;

- Lack of standards for clinical patient care, resulting in poor quality of care; and

- Lack of hospital management skills, which results in inefficiently run hospitals, poorly managed staff, lack of supplies, and inoperable equipment due to lack of maintenance.10

Response: The Hospital Management Improvement Initiative

REACH began helping to rebuild the health sector in 2003. Initial efforts focused on expanding basic services, and in two years we have moved from 5% to 77% coverage of the population of Afghanistan. In 2004, the contract was amended to include the hospital sector, with a focus on provincial hospitals. REACH developed the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative to build the clinical and management capacity of hospitals so that:

- Health services are delivered more efficiently;

- The quality of services are improved;

- The population has increased access to hospital services; and

- There is a positive impact on health status—especially on the morbidity and mortality of women and children.

Introducing clinical and management improvements, combined with appropriate resources, will improve quality of care, increase access to hospital services, and streamline hospital operations. These improvements will ultimately result in achievement of the goals of improved health status, improved patient and community satisfaction with hospitals, and an improved referral system for Afghanistan.

Although the need was great, it was not possible to train the management team at each hospital in Afghanistan. Instead, clinical and management capacities at the provincial and central hospitals were strengthened through training, mentoring, networking and modeling, and provision of resources.

Training

The Standards Based Management/Performance Quality Improvement approach that JHPIEGO has successfully developed and used to improve the quality of reproductive health services in many resource-poor settings has been expanded and adapted by REACH into a comprehensive approach to improve hospital management in Afghanistan. This process includes all clinical services (surgery, anesthesia, emergency care, pediatrics, infection prevention, and blood transfusion and blood banks) and management systems (governance, facilities and equipment management, pharmacy management, human resource systems) for general hospitals.

Standards were developed in each of these areas, and training modules developed. Eight workshops have been held to train key staff from each hospital, who return to their hospitals to introduce the standards to their medical and administrative staff. Each workshop produces a plan for implementing the standards according to the circumstances of each hospital. The training is incremental. For instance, rather than doing a one- to two-week workshop presenting all the training modules, two modules on standards (usually one clinical and one management area) are presented. Two new modules are presented quarterly thereafter, to prevent information overload, allow trainees to integrate what they have learned with real day-to-day management, and avoid the problem of hospitals being left without leadership for an extended period.

Mentoring

A skilled hospital management advisor visits the hospitals regularly so managers have the opportunity to work with a mentor to apply what they have learned to their hospitals. This practical experience involves applying principles to real-life situations with someone experienced enough to help overcome obstacles not anticipated in the workshops. Mentors from REACH and the Ministry of Public Health visit the provincial hospitals to discuss problems, review progress, talk about problems that prevented achievement of goals, and set goals for the next three-month period.

The first four provincial hospitals selected for this intervention are all in areas formerly controlled by the Taliban, and security issues have added other challenges to this program because of repeated terrorist attacks on non-governmental organizations and people employed by international organizations. The mentors involved must speak Pashto, the local language, and integrate into the culture so they do not attract attention or create local opposition. Mentoring is a necessary but dangerous activity for the success of the program.

Networking and Modeling

As more hospital managers and senior clinicians are trained through this program, networking becomes another important tool. The network uses meetings twice a year for two days in a participating hospital to provide an opportunity for hospital managers to discuss common issues and develop system-wide solutions. Between these meetings, hospital managers in the same region exchange visits to learn from each other. REACH facilitates this networking using e-mail (some of the provincial hospitals have Internet access, which has dramatically increased their participation in evidence-based approaches), dissemination of reports, and passing on requests for communication between hospitals. These formal meetings and informal exchanges permit hospital managers to interact about common problems and learn how other hospitals have solved those problems. This networking will slowly expand to cover more provincial hospitals and will assist in expanding the number of trainers and mentors.

Modeling means trying new systems and methods generated by the trainees to address their self-identified problems. Improvements in five provincial hospitals (in Khost, Paktika, Paktia, Ghazni, and Badakhshan) will provide a model that demonstrates to the public that hospitals can be well run and serve the community. These hospitals can also be used as training grounds for other hospital managers from around the country as the initiative expands to more of the remaining 28 provincial hospitals. The goal is to develop optimism and creativity because one of the main barriers in training is that some managers have difficulty imagining things being different because they feel the system “has always been broken.” When trainees see that other hospitals have successfully tried new approaches, they will consider a broader range of possibilities for their own hospitals.

Resources

Along with the management improvements achieved through training, mentoring, and networking, additional resources are needed to improve hospital services. REACH has been the conduit for U.S. government funding, providing $2.6 million in critical resources to drive improvements in the five provincial hospitals. These funds are channeled through the contracted nongovernmental organizations, which hire staff and pay decent salaries.

The average hospital physician in the Ministry of Public Health is paid $50 a month. In this setting “under-the-table” charges for clinical services are common, and physicians usually leave the hospital by lunch to attend to their private clinics. This initiative pays physicians up to $500 a month with the expectations that they will work a full day, provide 24-hour emergency coverage, and not charge patients. Eighteen months of experience suggest that these expectations are being met. Resources are also used for remodeling facilities, purchasing equipment and supplies, and providing essential medicines. The management standards developed are designed to make rational use of these scarce resources.

Prerequisites for the Initiative

Two key prerequisites for starting the Hospital Management Initiative were:

- Identifying where standards had to be developed: REACH has assisted the Ministry of Public Health to identify the standards that must be developed: responsibilities of hospitals to the community, patient care (clinical care), human resource management, management systems, environmental health, and leadership and management.10 “Areas of Standards for Hospitals in Afghanistan” shows the standards that have been or are to be developed. (See sidebar at left.)

- Essential Package of Hospital Services: To ensure that donor support does not stimulate a proliferation of hospitals and high-tech equipment that are not appropriate or sustainable for Afghanistan, REACH has been helping the Ministry of Public Health define the levels of hospitals (district, provincial, regional), the populations they serve, the services they offer, and the equipment, staff, supplies, and pharmaceuticals they need. The result was the publication of the Essential Package of Hospital Services, which defines these for each of the three levels of hospitals in the country, in 2005. This package will provide guidance for Afghanistan’s hospitals for the coming decade, much as the Basic Package of Health Services has done for primary healthcare services. The hospital package will also support long-term planning and help the Ministry make the best use of donor assistance for redeveloping the hospital sector.

Developing and Implementing Standards

Standards-based management begins by identifying existing clinical guidelines and standards developed by American or international specialty societies. Specialist consultants in each clinical area with many years’ experience in Afghanistan (some of them Afghan-American physicians) are contracted to develop these standards and then adapt them to the Afghan context, in consultation with physicians in Afghanistan.

For example, standards for acute abdominal pain had to be adapted to a situation where CAT scans and ultrasounds are not readily available, and the lack of electrolyte laboratory capacity in hospitals stimulated physicians to adapt standards for shock, and fluid and electrolyte balance that do not rely on knowing electrolyte levels. The standards development teams aimed to raise the standards of Afghan hospitals to a realistic extent but not set the bar so high that improvement was unattainable.

After the standards were developed, clinicians from Afghan hospitals reviewed and revised the standards to ensure that they were appropriate. This review also served as a means of training because the participants were able and eager to question the contracted expert about the standards in developed countries and the evidence supporting those standards. Once the standards are revised, a workshop is held to introduce them to hospital staff. The hospital teams then develop an action plan for introducing the standards into their facilities.

Quality improvement teams at each of the five hospitals take responsibility for shepherding the action plans through implementation. An advisor visits each hospital quarterly to review progress, assess barriers, and help hospital staff develop ways to overcome problems and accelerate standards implementation. During the mentor’s first visit after new standards have been introduced, he performs a baseline assessment of the hospital’s current compliance with the standards. This serves as a benchmark for future measurement of progress in meeting the standards.

The Results

The hospitals have been enthusiastic about this process and the gains they have seen in the quality of care at their facilities. “We have made more progress in four months of the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative than we made in the previous five years with many other donors because this methodology is sound and appropriate for Afghanistan,” said Dr. Mohammed Ismael, the director of Ghazni Provincial Hospital.

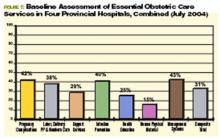

One example of the process and results was the first area in which standards were developed—essential obstetric care. Physicians examined seven components of the quality of emergency obstetric care: handling of pregnancy complications; labor, delivery, and postpartum and newborn care; support services; infection prevention; health education given to families and mothers; human, physical, and material resources; and management systems in the obstetrics/gynecology department. After the standards were established, the first step was to find out where each hospital stood in meeting them. (For the combined results of that first baseline assessment for four hospitals, see Figure 1, p. 20.)

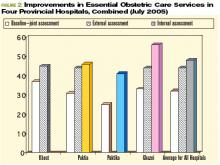

The changes in standards for emergency obstetric care at the hospitals from July 2004 to July 2005 have been impressive. The overall composite scores for emergency obstetric care for the four hospitals have improved from 31% at the baseline assessment to 47%. Here are the average improvements in the same four hospitals over one year:

Lessons Learned

The principal lesson learned through this hospital management improvement initiative is that combining clinical and management improvements can create innovation in a developing country. Improvements are made throughout a hospital—not just in one clinical area. Second, mentoring has proven essential as a follow-up to training. The training alone will not bring about significant positive changes. Only with on-site visitation is there the opportunity to integrate new knowledge with practical implementation issues that have proven troublesome to overcome. Third, setting standards is key to the sustainability of improvements. Training individuals in skills is helpful but is not sustainable if those trained staff depart. Using hospital teams and common standards throughout different hospitals leads to institutionalization of the process.

Staff motivation has also proven to be essential to sustainability. Staff have been motivated because they see that many positive changes are within their control; they do not have to wait for someone else to make an improvement before they can introduce positive change. An ethic of continuous quality improvement is achieved through staff who are proud of the changes they have introduced. The iterative nature of this process has been essential to quality improvement: The standards are continually revisited and revised as needed. At times, new standards for other areas are developed when the hospitals need them. Finally, providing resources to pay adequate salaries, renovate facilities, buy equipment and supplies, and provide essential medicines are all important elements of this success.

This method has proven successful in such a short time that the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Mohammad Amin Fatimie, has expressed his desire to extend it to many other hospitals in the country in an effort to improve the quality of hospital care throughout Afghani-stan. The U.S. Agency for International Development and MSH have agreed to support this request, and the program will expand in future years. TH

Dr. Hartman, is a family physician with subspecialty training in infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. He serves as the technical director and deputy chief of party of the REACH Project, based in Kabul. Dr. Newbrander is a health economist who has served in Afghanistan since 2002 as a senior advisor to the Ministry of Health. He is currently Health Financing and Hospital Management Advisor for the USAID-funded REACH Project.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this article was provided by the United States Agency for International Development under the REACH Project, contract number EEE-C-00-03-00015-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

References

- Newbrander W, Ickx P, Leitch GH. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Pol Rev. 2003;4.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United Nations Children’s Fund. Maternal mortality in Afghanistan: magnitude, causes, risk factors and preventability. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864-870.

- Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Health Policy in Afghanistan: Two Years of Rapid Change: A Review of the Process from 2001 to 2003. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005.

- Afghanistan’s health challenge. Lancet. 2003;362:841.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). The Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: TISA; 2003.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). Hospital Policy for Afghanistan’s Health System. Kabul: TISA; 2004.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), Management Sciences for Health. Afghanistan national health resources assessment: Preliminary results. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- A crucial time for Afghanistan’s fledgling health system. Lancet. 2005; 365:819-820.

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: MOPH; 2005.

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the first article in that effort.

Over the past two decades Afghanistan became known to many for its invasion by the Soviets (the war the mujahideen fought against its occupiers), the bloody infighting that followed the Soviet withdrawal, and the horrific rule of the Taliban. The expulsion of the Taliban in 2001 by coalition forces and Afghanistan’s recent steps toward democracy have made it the focus of much world attention.

Afghanistan’s health situation is among the worst in the world.1 The data that emerged in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban reported a maternal mortality ratio of 1,600 per 100,000 women, which translates into a lifetime risk that one in six women will die of complications of pregnancy and delivery.2-3 The same study showed severe inequities in mortality rates between rural and urban areas: Kabul’s maternal mortality ratio is 400 per 100,000, whereas in rural Badakhshan province it is 6,500 per 100,000—the highest recorded rate in the world in modern times.2 Afghanistan is the only country in the world where men outlive women. Twenty-five percent of children die before age five—most of treatable diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and preventable diseases such as measles and pertussis. Children, women, and men face risks from communicable diseases that are among the highest in the world, as well as the risk of death or serious injury from landmines and other unexploded ordnance.

In this setting, the Ministry of Public Health made two major decisions in 2002: All health services would be contracted to nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry would be the steward of the health system, setting policies and regulating services; and the Basic Package of Health Services would be the main policy that all service providers would follow.4-5 This package defines specific services focused on women’s and children’s needs by level and by appropriate intervention.6 The Basic Package also stresses equity by giving priority to rural over urban areas and to women’s participation over men’s. A related policy on hospitals limits spending on hospitals to 40% of the national health budget, with the remaining 60% to be spent on basic health services.7

State of Hospitals

Many health facilities—especially hospitals—had been damaged or destroyed. A survey of all health facilities in the country by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in 2002, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other donors, found that 35% of the facilities were severely damaged due to war or natural disasters, and the rest failed to meet current World Health Organization standards.8 A second major concern was the lack of health professionals, many of whom had fled the country during the war years. Finally, the staff remaining, especially physicians, lacked good clinical training and continuing education, which compromised quality of care. The Rural Expansion of Afghanistan’s Community-based Healthcare (REACH) was designed to address all these issues. REACH is a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by MSH and the Afghan Ministry of Public Health. Partners include the Academy for Educational Development; JHPIEGO (an international health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University); Technical Assistance, Inc., and the University of Massachusetts/Amherst.

Hospitals are a critical element of the Afghan health system because they are part of the referral system that plays an essential role in reducing high maternal and early childhood mortality rates. In addition, hospitals use many of the most skilled health workers and the financial resources of the health system. Dramatic improvements in hospital management are needed so hospitals can use these scarce resources effectively and efficiently.9

Challenges

In brief, the key issues facing hospitals in the Afghan health system are:

- Maldistribution of hospitals and hospital beds throughout the country, which means a lack of equitable access to hospital care. People in urban areas have access but semi-urban and rural populations have limited access. For example, Kabul has 1.28 beds per 1,000 people while the provinces have only .22 per 1,000;

- Lack of standards for clinical patient care, resulting in poor quality of care; and

- Lack of hospital management skills, which results in inefficiently run hospitals, poorly managed staff, lack of supplies, and inoperable equipment due to lack of maintenance.10

Response: The Hospital Management Improvement Initiative

REACH began helping to rebuild the health sector in 2003. Initial efforts focused on expanding basic services, and in two years we have moved from 5% to 77% coverage of the population of Afghanistan. In 2004, the contract was amended to include the hospital sector, with a focus on provincial hospitals. REACH developed the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative to build the clinical and management capacity of hospitals so that:

- Health services are delivered more efficiently;

- The quality of services are improved;

- The population has increased access to hospital services; and

- There is a positive impact on health status—especially on the morbidity and mortality of women and children.

Introducing clinical and management improvements, combined with appropriate resources, will improve quality of care, increase access to hospital services, and streamline hospital operations. These improvements will ultimately result in achievement of the goals of improved health status, improved patient and community satisfaction with hospitals, and an improved referral system for Afghanistan.

Although the need was great, it was not possible to train the management team at each hospital in Afghanistan. Instead, clinical and management capacities at the provincial and central hospitals were strengthened through training, mentoring, networking and modeling, and provision of resources.

Training

The Standards Based Management/Performance Quality Improvement approach that JHPIEGO has successfully developed and used to improve the quality of reproductive health services in many resource-poor settings has been expanded and adapted by REACH into a comprehensive approach to improve hospital management in Afghanistan. This process includes all clinical services (surgery, anesthesia, emergency care, pediatrics, infection prevention, and blood transfusion and blood banks) and management systems (governance, facilities and equipment management, pharmacy management, human resource systems) for general hospitals.

Standards were developed in each of these areas, and training modules developed. Eight workshops have been held to train key staff from each hospital, who return to their hospitals to introduce the standards to their medical and administrative staff. Each workshop produces a plan for implementing the standards according to the circumstances of each hospital. The training is incremental. For instance, rather than doing a one- to two-week workshop presenting all the training modules, two modules on standards (usually one clinical and one management area) are presented. Two new modules are presented quarterly thereafter, to prevent information overload, allow trainees to integrate what they have learned with real day-to-day management, and avoid the problem of hospitals being left without leadership for an extended period.

Mentoring

A skilled hospital management advisor visits the hospitals regularly so managers have the opportunity to work with a mentor to apply what they have learned to their hospitals. This practical experience involves applying principles to real-life situations with someone experienced enough to help overcome obstacles not anticipated in the workshops. Mentors from REACH and the Ministry of Public Health visit the provincial hospitals to discuss problems, review progress, talk about problems that prevented achievement of goals, and set goals for the next three-month period.

The first four provincial hospitals selected for this intervention are all in areas formerly controlled by the Taliban, and security issues have added other challenges to this program because of repeated terrorist attacks on non-governmental organizations and people employed by international organizations. The mentors involved must speak Pashto, the local language, and integrate into the culture so they do not attract attention or create local opposition. Mentoring is a necessary but dangerous activity for the success of the program.

Networking and Modeling

As more hospital managers and senior clinicians are trained through this program, networking becomes another important tool. The network uses meetings twice a year for two days in a participating hospital to provide an opportunity for hospital managers to discuss common issues and develop system-wide solutions. Between these meetings, hospital managers in the same region exchange visits to learn from each other. REACH facilitates this networking using e-mail (some of the provincial hospitals have Internet access, which has dramatically increased their participation in evidence-based approaches), dissemination of reports, and passing on requests for communication between hospitals. These formal meetings and informal exchanges permit hospital managers to interact about common problems and learn how other hospitals have solved those problems. This networking will slowly expand to cover more provincial hospitals and will assist in expanding the number of trainers and mentors.

Modeling means trying new systems and methods generated by the trainees to address their self-identified problems. Improvements in five provincial hospitals (in Khost, Paktika, Paktia, Ghazni, and Badakhshan) will provide a model that demonstrates to the public that hospitals can be well run and serve the community. These hospitals can also be used as training grounds for other hospital managers from around the country as the initiative expands to more of the remaining 28 provincial hospitals. The goal is to develop optimism and creativity because one of the main barriers in training is that some managers have difficulty imagining things being different because they feel the system “has always been broken.” When trainees see that other hospitals have successfully tried new approaches, they will consider a broader range of possibilities for their own hospitals.

Resources

Along with the management improvements achieved through training, mentoring, and networking, additional resources are needed to improve hospital services. REACH has been the conduit for U.S. government funding, providing $2.6 million in critical resources to drive improvements in the five provincial hospitals. These funds are channeled through the contracted nongovernmental organizations, which hire staff and pay decent salaries.

The average hospital physician in the Ministry of Public Health is paid $50 a month. In this setting “under-the-table” charges for clinical services are common, and physicians usually leave the hospital by lunch to attend to their private clinics. This initiative pays physicians up to $500 a month with the expectations that they will work a full day, provide 24-hour emergency coverage, and not charge patients. Eighteen months of experience suggest that these expectations are being met. Resources are also used for remodeling facilities, purchasing equipment and supplies, and providing essential medicines. The management standards developed are designed to make rational use of these scarce resources.

Prerequisites for the Initiative

Two key prerequisites for starting the Hospital Management Initiative were:

- Identifying where standards had to be developed: REACH has assisted the Ministry of Public Health to identify the standards that must be developed: responsibilities of hospitals to the community, patient care (clinical care), human resource management, management systems, environmental health, and leadership and management.10 “Areas of Standards for Hospitals in Afghanistan” shows the standards that have been or are to be developed. (See sidebar at left.)

- Essential Package of Hospital Services: To ensure that donor support does not stimulate a proliferation of hospitals and high-tech equipment that are not appropriate or sustainable for Afghanistan, REACH has been helping the Ministry of Public Health define the levels of hospitals (district, provincial, regional), the populations they serve, the services they offer, and the equipment, staff, supplies, and pharmaceuticals they need. The result was the publication of the Essential Package of Hospital Services, which defines these for each of the three levels of hospitals in the country, in 2005. This package will provide guidance for Afghanistan’s hospitals for the coming decade, much as the Basic Package of Health Services has done for primary healthcare services. The hospital package will also support long-term planning and help the Ministry make the best use of donor assistance for redeveloping the hospital sector.

Developing and Implementing Standards

Standards-based management begins by identifying existing clinical guidelines and standards developed by American or international specialty societies. Specialist consultants in each clinical area with many years’ experience in Afghanistan (some of them Afghan-American physicians) are contracted to develop these standards and then adapt them to the Afghan context, in consultation with physicians in Afghanistan.

For example, standards for acute abdominal pain had to be adapted to a situation where CAT scans and ultrasounds are not readily available, and the lack of electrolyte laboratory capacity in hospitals stimulated physicians to adapt standards for shock, and fluid and electrolyte balance that do not rely on knowing electrolyte levels. The standards development teams aimed to raise the standards of Afghan hospitals to a realistic extent but not set the bar so high that improvement was unattainable.

After the standards were developed, clinicians from Afghan hospitals reviewed and revised the standards to ensure that they were appropriate. This review also served as a means of training because the participants were able and eager to question the contracted expert about the standards in developed countries and the evidence supporting those standards. Once the standards are revised, a workshop is held to introduce them to hospital staff. The hospital teams then develop an action plan for introducing the standards into their facilities.

Quality improvement teams at each of the five hospitals take responsibility for shepherding the action plans through implementation. An advisor visits each hospital quarterly to review progress, assess barriers, and help hospital staff develop ways to overcome problems and accelerate standards implementation. During the mentor’s first visit after new standards have been introduced, he performs a baseline assessment of the hospital’s current compliance with the standards. This serves as a benchmark for future measurement of progress in meeting the standards.

The Results

The hospitals have been enthusiastic about this process and the gains they have seen in the quality of care at their facilities. “We have made more progress in four months of the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative than we made in the previous five years with many other donors because this methodology is sound and appropriate for Afghanistan,” said Dr. Mohammed Ismael, the director of Ghazni Provincial Hospital.

One example of the process and results was the first area in which standards were developed—essential obstetric care. Physicians examined seven components of the quality of emergency obstetric care: handling of pregnancy complications; labor, delivery, and postpartum and newborn care; support services; infection prevention; health education given to families and mothers; human, physical, and material resources; and management systems in the obstetrics/gynecology department. After the standards were established, the first step was to find out where each hospital stood in meeting them. (For the combined results of that first baseline assessment for four hospitals, see Figure 1, p. 20.)

The changes in standards for emergency obstetric care at the hospitals from July 2004 to July 2005 have been impressive. The overall composite scores for emergency obstetric care for the four hospitals have improved from 31% at the baseline assessment to 47%. Here are the average improvements in the same four hospitals over one year:

Lessons Learned

The principal lesson learned through this hospital management improvement initiative is that combining clinical and management improvements can create innovation in a developing country. Improvements are made throughout a hospital—not just in one clinical area. Second, mentoring has proven essential as a follow-up to training. The training alone will not bring about significant positive changes. Only with on-site visitation is there the opportunity to integrate new knowledge with practical implementation issues that have proven troublesome to overcome. Third, setting standards is key to the sustainability of improvements. Training individuals in skills is helpful but is not sustainable if those trained staff depart. Using hospital teams and common standards throughout different hospitals leads to institutionalization of the process.

Staff motivation has also proven to be essential to sustainability. Staff have been motivated because they see that many positive changes are within their control; they do not have to wait for someone else to make an improvement before they can introduce positive change. An ethic of continuous quality improvement is achieved through staff who are proud of the changes they have introduced. The iterative nature of this process has been essential to quality improvement: The standards are continually revisited and revised as needed. At times, new standards for other areas are developed when the hospitals need them. Finally, providing resources to pay adequate salaries, renovate facilities, buy equipment and supplies, and provide essential medicines are all important elements of this success.

This method has proven successful in such a short time that the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Mohammad Amin Fatimie, has expressed his desire to extend it to many other hospitals in the country in an effort to improve the quality of hospital care throughout Afghani-stan. The U.S. Agency for International Development and MSH have agreed to support this request, and the program will expand in future years. TH

Dr. Hartman, is a family physician with subspecialty training in infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. He serves as the technical director and deputy chief of party of the REACH Project, based in Kabul. Dr. Newbrander is a health economist who has served in Afghanistan since 2002 as a senior advisor to the Ministry of Health. He is currently Health Financing and Hospital Management Advisor for the USAID-funded REACH Project.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this article was provided by the United States Agency for International Development under the REACH Project, contract number EEE-C-00-03-00015-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

References

- Newbrander W, Ickx P, Leitch GH. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Pol Rev. 2003;4.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United Nations Children’s Fund. Maternal mortality in Afghanistan: magnitude, causes, risk factors and preventability. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864-870.

- Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Health Policy in Afghanistan: Two Years of Rapid Change: A Review of the Process from 2001 to 2003. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005.

- Afghanistan’s health challenge. Lancet. 2003;362:841.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). The Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: TISA; 2003.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). Hospital Policy for Afghanistan’s Health System. Kabul: TISA; 2004.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), Management Sciences for Health. Afghanistan national health resources assessment: Preliminary results. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- A crucial time for Afghanistan’s fledgling health system. Lancet. 2005; 365:819-820.

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: MOPH; 2005.

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the first article in that effort.

Over the past two decades Afghanistan became known to many for its invasion by the Soviets (the war the mujahideen fought against its occupiers), the bloody infighting that followed the Soviet withdrawal, and the horrific rule of the Taliban. The expulsion of the Taliban in 2001 by coalition forces and Afghanistan’s recent steps toward democracy have made it the focus of much world attention.

Afghanistan’s health situation is among the worst in the world.1 The data that emerged in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban reported a maternal mortality ratio of 1,600 per 100,000 women, which translates into a lifetime risk that one in six women will die of complications of pregnancy and delivery.2-3 The same study showed severe inequities in mortality rates between rural and urban areas: Kabul’s maternal mortality ratio is 400 per 100,000, whereas in rural Badakhshan province it is 6,500 per 100,000—the highest recorded rate in the world in modern times.2 Afghanistan is the only country in the world where men outlive women. Twenty-five percent of children die before age five—most of treatable diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and preventable diseases such as measles and pertussis. Children, women, and men face risks from communicable diseases that are among the highest in the world, as well as the risk of death or serious injury from landmines and other unexploded ordnance.

In this setting, the Ministry of Public Health made two major decisions in 2002: All health services would be contracted to nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry would be the steward of the health system, setting policies and regulating services; and the Basic Package of Health Services would be the main policy that all service providers would follow.4-5 This package defines specific services focused on women’s and children’s needs by level and by appropriate intervention.6 The Basic Package also stresses equity by giving priority to rural over urban areas and to women’s participation over men’s. A related policy on hospitals limits spending on hospitals to 40% of the national health budget, with the remaining 60% to be spent on basic health services.7

State of Hospitals

Many health facilities—especially hospitals—had been damaged or destroyed. A survey of all health facilities in the country by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in 2002, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other donors, found that 35% of the facilities were severely damaged due to war or natural disasters, and the rest failed to meet current World Health Organization standards.8 A second major concern was the lack of health professionals, many of whom had fled the country during the war years. Finally, the staff remaining, especially physicians, lacked good clinical training and continuing education, which compromised quality of care. The Rural Expansion of Afghanistan’s Community-based Healthcare (REACH) was designed to address all these issues. REACH is a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by MSH and the Afghan Ministry of Public Health. Partners include the Academy for Educational Development; JHPIEGO (an international health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University); Technical Assistance, Inc., and the University of Massachusetts/Amherst.

Hospitals are a critical element of the Afghan health system because they are part of the referral system that plays an essential role in reducing high maternal and early childhood mortality rates. In addition, hospitals use many of the most skilled health workers and the financial resources of the health system. Dramatic improvements in hospital management are needed so hospitals can use these scarce resources effectively and efficiently.9

Challenges

In brief, the key issues facing hospitals in the Afghan health system are:

- Maldistribution of hospitals and hospital beds throughout the country, which means a lack of equitable access to hospital care. People in urban areas have access but semi-urban and rural populations have limited access. For example, Kabul has 1.28 beds per 1,000 people while the provinces have only .22 per 1,000;

- Lack of standards for clinical patient care, resulting in poor quality of care; and

- Lack of hospital management skills, which results in inefficiently run hospitals, poorly managed staff, lack of supplies, and inoperable equipment due to lack of maintenance.10

Response: The Hospital Management Improvement Initiative

REACH began helping to rebuild the health sector in 2003. Initial efforts focused on expanding basic services, and in two years we have moved from 5% to 77% coverage of the population of Afghanistan. In 2004, the contract was amended to include the hospital sector, with a focus on provincial hospitals. REACH developed the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative to build the clinical and management capacity of hospitals so that:

- Health services are delivered more efficiently;

- The quality of services are improved;

- The population has increased access to hospital services; and

- There is a positive impact on health status—especially on the morbidity and mortality of women and children.

Introducing clinical and management improvements, combined with appropriate resources, will improve quality of care, increase access to hospital services, and streamline hospital operations. These improvements will ultimately result in achievement of the goals of improved health status, improved patient and community satisfaction with hospitals, and an improved referral system for Afghanistan.

Although the need was great, it was not possible to train the management team at each hospital in Afghanistan. Instead, clinical and management capacities at the provincial and central hospitals were strengthened through training, mentoring, networking and modeling, and provision of resources.

Training

The Standards Based Management/Performance Quality Improvement approach that JHPIEGO has successfully developed and used to improve the quality of reproductive health services in many resource-poor settings has been expanded and adapted by REACH into a comprehensive approach to improve hospital management in Afghanistan. This process includes all clinical services (surgery, anesthesia, emergency care, pediatrics, infection prevention, and blood transfusion and blood banks) and management systems (governance, facilities and equipment management, pharmacy management, human resource systems) for general hospitals.

Standards were developed in each of these areas, and training modules developed. Eight workshops have been held to train key staff from each hospital, who return to their hospitals to introduce the standards to their medical and administrative staff. Each workshop produces a plan for implementing the standards according to the circumstances of each hospital. The training is incremental. For instance, rather than doing a one- to two-week workshop presenting all the training modules, two modules on standards (usually one clinical and one management area) are presented. Two new modules are presented quarterly thereafter, to prevent information overload, allow trainees to integrate what they have learned with real day-to-day management, and avoid the problem of hospitals being left without leadership for an extended period.

Mentoring

A skilled hospital management advisor visits the hospitals regularly so managers have the opportunity to work with a mentor to apply what they have learned to their hospitals. This practical experience involves applying principles to real-life situations with someone experienced enough to help overcome obstacles not anticipated in the workshops. Mentors from REACH and the Ministry of Public Health visit the provincial hospitals to discuss problems, review progress, talk about problems that prevented achievement of goals, and set goals for the next three-month period.

The first four provincial hospitals selected for this intervention are all in areas formerly controlled by the Taliban, and security issues have added other challenges to this program because of repeated terrorist attacks on non-governmental organizations and people employed by international organizations. The mentors involved must speak Pashto, the local language, and integrate into the culture so they do not attract attention or create local opposition. Mentoring is a necessary but dangerous activity for the success of the program.

Networking and Modeling

As more hospital managers and senior clinicians are trained through this program, networking becomes another important tool. The network uses meetings twice a year for two days in a participating hospital to provide an opportunity for hospital managers to discuss common issues and develop system-wide solutions. Between these meetings, hospital managers in the same region exchange visits to learn from each other. REACH facilitates this networking using e-mail (some of the provincial hospitals have Internet access, which has dramatically increased their participation in evidence-based approaches), dissemination of reports, and passing on requests for communication between hospitals. These formal meetings and informal exchanges permit hospital managers to interact about common problems and learn how other hospitals have solved those problems. This networking will slowly expand to cover more provincial hospitals and will assist in expanding the number of trainers and mentors.

Modeling means trying new systems and methods generated by the trainees to address their self-identified problems. Improvements in five provincial hospitals (in Khost, Paktika, Paktia, Ghazni, and Badakhshan) will provide a model that demonstrates to the public that hospitals can be well run and serve the community. These hospitals can also be used as training grounds for other hospital managers from around the country as the initiative expands to more of the remaining 28 provincial hospitals. The goal is to develop optimism and creativity because one of the main barriers in training is that some managers have difficulty imagining things being different because they feel the system “has always been broken.” When trainees see that other hospitals have successfully tried new approaches, they will consider a broader range of possibilities for their own hospitals.

Resources

Along with the management improvements achieved through training, mentoring, and networking, additional resources are needed to improve hospital services. REACH has been the conduit for U.S. government funding, providing $2.6 million in critical resources to drive improvements in the five provincial hospitals. These funds are channeled through the contracted nongovernmental organizations, which hire staff and pay decent salaries.

The average hospital physician in the Ministry of Public Health is paid $50 a month. In this setting “under-the-table” charges for clinical services are common, and physicians usually leave the hospital by lunch to attend to their private clinics. This initiative pays physicians up to $500 a month with the expectations that they will work a full day, provide 24-hour emergency coverage, and not charge patients. Eighteen months of experience suggest that these expectations are being met. Resources are also used for remodeling facilities, purchasing equipment and supplies, and providing essential medicines. The management standards developed are designed to make rational use of these scarce resources.

Prerequisites for the Initiative

Two key prerequisites for starting the Hospital Management Initiative were:

- Identifying where standards had to be developed: REACH has assisted the Ministry of Public Health to identify the standards that must be developed: responsibilities of hospitals to the community, patient care (clinical care), human resource management, management systems, environmental health, and leadership and management.10 “Areas of Standards for Hospitals in Afghanistan” shows the standards that have been or are to be developed. (See sidebar at left.)

- Essential Package of Hospital Services: To ensure that donor support does not stimulate a proliferation of hospitals and high-tech equipment that are not appropriate or sustainable for Afghanistan, REACH has been helping the Ministry of Public Health define the levels of hospitals (district, provincial, regional), the populations they serve, the services they offer, and the equipment, staff, supplies, and pharmaceuticals they need. The result was the publication of the Essential Package of Hospital Services, which defines these for each of the three levels of hospitals in the country, in 2005. This package will provide guidance for Afghanistan’s hospitals for the coming decade, much as the Basic Package of Health Services has done for primary healthcare services. The hospital package will also support long-term planning and help the Ministry make the best use of donor assistance for redeveloping the hospital sector.

Developing and Implementing Standards

Standards-based management begins by identifying existing clinical guidelines and standards developed by American or international specialty societies. Specialist consultants in each clinical area with many years’ experience in Afghanistan (some of them Afghan-American physicians) are contracted to develop these standards and then adapt them to the Afghan context, in consultation with physicians in Afghanistan.

For example, standards for acute abdominal pain had to be adapted to a situation where CAT scans and ultrasounds are not readily available, and the lack of electrolyte laboratory capacity in hospitals stimulated physicians to adapt standards for shock, and fluid and electrolyte balance that do not rely on knowing electrolyte levels. The standards development teams aimed to raise the standards of Afghan hospitals to a realistic extent but not set the bar so high that improvement was unattainable.

After the standards were developed, clinicians from Afghan hospitals reviewed and revised the standards to ensure that they were appropriate. This review also served as a means of training because the participants were able and eager to question the contracted expert about the standards in developed countries and the evidence supporting those standards. Once the standards are revised, a workshop is held to introduce them to hospital staff. The hospital teams then develop an action plan for introducing the standards into their facilities.

Quality improvement teams at each of the five hospitals take responsibility for shepherding the action plans through implementation. An advisor visits each hospital quarterly to review progress, assess barriers, and help hospital staff develop ways to overcome problems and accelerate standards implementation. During the mentor’s first visit after new standards have been introduced, he performs a baseline assessment of the hospital’s current compliance with the standards. This serves as a benchmark for future measurement of progress in meeting the standards.

The Results

The hospitals have been enthusiastic about this process and the gains they have seen in the quality of care at their facilities. “We have made more progress in four months of the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative than we made in the previous five years with many other donors because this methodology is sound and appropriate for Afghanistan,” said Dr. Mohammed Ismael, the director of Ghazni Provincial Hospital.

One example of the process and results was the first area in which standards were developed—essential obstetric care. Physicians examined seven components of the quality of emergency obstetric care: handling of pregnancy complications; labor, delivery, and postpartum and newborn care; support services; infection prevention; health education given to families and mothers; human, physical, and material resources; and management systems in the obstetrics/gynecology department. After the standards were established, the first step was to find out where each hospital stood in meeting them. (For the combined results of that first baseline assessment for four hospitals, see Figure 1, p. 20.)

The changes in standards for emergency obstetric care at the hospitals from July 2004 to July 2005 have been impressive. The overall composite scores for emergency obstetric care for the four hospitals have improved from 31% at the baseline assessment to 47%. Here are the average improvements in the same four hospitals over one year:

Lessons Learned

The principal lesson learned through this hospital management improvement initiative is that combining clinical and management improvements can create innovation in a developing country. Improvements are made throughout a hospital—not just in one clinical area. Second, mentoring has proven essential as a follow-up to training. The training alone will not bring about significant positive changes. Only with on-site visitation is there the opportunity to integrate new knowledge with practical implementation issues that have proven troublesome to overcome. Third, setting standards is key to the sustainability of improvements. Training individuals in skills is helpful but is not sustainable if those trained staff depart. Using hospital teams and common standards throughout different hospitals leads to institutionalization of the process.

Staff motivation has also proven to be essential to sustainability. Staff have been motivated because they see that many positive changes are within their control; they do not have to wait for someone else to make an improvement before they can introduce positive change. An ethic of continuous quality improvement is achieved through staff who are proud of the changes they have introduced. The iterative nature of this process has been essential to quality improvement: The standards are continually revisited and revised as needed. At times, new standards for other areas are developed when the hospitals need them. Finally, providing resources to pay adequate salaries, renovate facilities, buy equipment and supplies, and provide essential medicines are all important elements of this success.

This method has proven successful in such a short time that the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Mohammad Amin Fatimie, has expressed his desire to extend it to many other hospitals in the country in an effort to improve the quality of hospital care throughout Afghani-stan. The U.S. Agency for International Development and MSH have agreed to support this request, and the program will expand in future years. TH

Dr. Hartman, is a family physician with subspecialty training in infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. He serves as the technical director and deputy chief of party of the REACH Project, based in Kabul. Dr. Newbrander is a health economist who has served in Afghanistan since 2002 as a senior advisor to the Ministry of Health. He is currently Health Financing and Hospital Management Advisor for the USAID-funded REACH Project.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this article was provided by the United States Agency for International Development under the REACH Project, contract number EEE-C-00-03-00015-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

References

- Newbrander W, Ickx P, Leitch GH. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Pol Rev. 2003;4.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United Nations Children’s Fund. Maternal mortality in Afghanistan: magnitude, causes, risk factors and preventability. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864-870.

- Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Health Policy in Afghanistan: Two Years of Rapid Change: A Review of the Process from 2001 to 2003. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005.

- Afghanistan’s health challenge. Lancet. 2003;362:841.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). The Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: TISA; 2003.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). Hospital Policy for Afghanistan’s Health System. Kabul: TISA; 2004.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), Management Sciences for Health. Afghanistan national health resources assessment: Preliminary results. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- A crucial time for Afghanistan’s fledgling health system. Lancet. 2005; 365:819-820.

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: MOPH; 2005.