User login

Aplastic anemia is a rare hematologic disorder marked by pancytopenia and a hypocellular marrow. Aplastic anemia results from either inherited or acquired causes, and the treatment approach varies significantly between the 2 causes. This article reviews the treatment of inherited and acquired forms of aplastic anemia. The approach to evaluation and diagnosis of aplastic anemia is reviewed in a separate article.

Inherited Aplastic Anemia

First-line treatment options for patients with inherited marrow failure syndromes (IMFS) are androgen therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). When evaluating patients for HSCT, it is critical to identify the presence of an IMFS, as the risk and mortality associated with the conditioning regimen, stem cell source, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and secondary malignancies differ between patients with IMFS and those with acquired marrow failure syndromes or hematologic malignancies.

Potential sibling donors need to be screened for donor candidacy as well as for the inherited defect.1 Among patients with Fanconi anemia or a telomere biology disorder, the stem cell source must be considered, with bone marrow demonstrating lower rates of acute GVHD than a peripheral blood stem cell source.2-4 In IMFS patients, the donor cell type may affect the choice of conditioning regimen.5,6 Reduced-intensity conditioning in lieu of myeloablative conditioning without total body irradiation has proved feasible in patients with Fanconi anemia, and is associated with a reduced risk of secondary malignancies.5,6 Incorporation of fludarabine in the conditioning regimen of patients without a matched sibling donor is associated with superior engraftment and survival2,5,7 compared to cyclophosphamide conditioning, which was historically used in matched related donors.6,8 The addition of fludarabine appears to be especially beneficial in older patients, in whom its use is associated with lower rates of graft failure, likely due to increased immunosuppression at the time of engraftment.7,9 Fludarabine has also been incorporated into conditioning regimens for patients with a telomere biology disorder, but outcomes data is limited.5

For patients presenting with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or a high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) who are subsequently diagnosed with an IMFS, treatment can be more complex, as these patients are at high risk for toxicity from standard chemotherapy. Limited data suggests that induction therapy and transplantation are feasible in this group of patients, and this approach is associated with increased overall survival (OS) despite lower OS rates than those of IMFS patients who present prior to the development of MDS or AML.10,11 Further work is needed to determine the optimal induction regimen that balances the risks of treatment-related mortality and complications associated with conditioning regimens, risk of relapse, and risk of secondary malignancies, especially in the cohort of patients diagnosed at an older age.

Acquired Aplastic Anemia

Supportive Care

While the workup and treatment plan is being established, attention should be directed at supportive care for prevention of complications. The most common complications leading to death in patients with significant pancytopenia and neutropenia are opportunistic infections and hemorrhagic complications.12

Transfusion support is critical to avoid symptomatic anemia and hemorrhagic complications related to thrombocytopenia, which typically occur with platelet counts lower than 10,000 cells/µL. However, transfusion carries the risk of alloimmunization (which may persist for years following transfusion) and transfusion-related graft versus host disease (trGVHD), and thus use of transfusion should be minimized when possible.13,14 Transfusion support is often required to prevent complications associated with thrombocytopenia and anemia; all blood products given to patients with aplastic anemia should be irradiated and leukoreduced to reduce the risk of both alloimmunization and trGVHD. Guidelines from the British Society for Haematology recommend routine screening for Rh and Kell antibodies to reduce the risk of alloimmunization.15 Infectious complications remain a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with aplastic anemia who have prolonged neutropenia (defined as an absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 500 cells/µL).16-19 Therefore, patients should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics with antipseudomonal coverage. In a study by Tichelli and colleagues evaluating the role of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with SAA receiving immunosuppressive therapy, 55% of all patient deaths were secondary to infection.20 There was no OS benefit seen in patients who received G-CSF, though a significantly lower rate of infection was observed in the G-CSF arm compared to those not receiving G-CSF (56% versus 81%, P = 0.006).This difference was largely driven by a decrease in infectious episodes in patients with very severe aplastic anemia (VSAA) treated with G-CSF as compared to those who did not receive this therapy (22% versus 48%, P = 0.014).20

Angio-invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and Zygomycetes (eg, Rhizopus, Mucor species) remain major causes of mortality related to opportunistic mycotic infections in patients with aplastic anemia.18 The infectious risk is directly related to the duration and severity of neutropenia, with one study demonstrating a significant increase in risk in AML patients with neutropenia lasting longer than 3 weeks.21 Invasive fungal infections carry a high mortality in patients with severe neutropenia, though due to earlier recognition and empiric antifungal therapy with extended-spectrum azoles, overall mortality secondary to invasive fungal infections is declining.19,22

While neutropenia related to cytotoxic chemotherapy is commonly associated with gram-negative bacteria due to disruption of mucosal barriers, patients with aplastic anemia have an increased incidence of gram-positive bacteremia with staphylococcal species compared to other neutropenic populations.18,19 This appears to be changing with time. Valdez and colleagues demonstrated a decrease in prevalence of coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections, increased prevalence of gram-positive bacilli bacteremia, and no change in prevalence of gram-negative bacteremia in patients with aplastic anemia treated between 1989 and 2008.22 Gram-negative bacteremia caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophila, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter, and Proteus has also been reported.19 Despite a lack of clinical trials investigating the role of antifungal and antibacterial prophylaxis for patients with aplastic anemia, most centers initiate antifungal prophylaxis in patients with severe aplastic anema (SAA) or VSAA with an anti-mold agent such as voriconazole or posaconazole (which has the additional benefit compared to voriconazole of covering Mucor species).17,23 This is especially true for patients who have received ATG or undergone HSCT. For antimicrobial prophylaxis, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic with a spectrum of activity against Pseudomonas should be considered for patients with an ANC < 500 cells/µL.17 Acyclovir or valacyclovir prophylaxis is recommended for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus. Cytomegalovirus reactivation is minimal in patients with aplastic anemia, unless multiple courses of ATG are used.

Iron overload is another complication the provider must be aware of in the setting of increased transfusions in aplastic anemia patients. Lee and colleagues demonstrated that iron chelation therapy using deferasirox is effective at reducing serum ferritin levels in patients with aplastic anemia (median ferritin level: 3254 ng/mL prior to therapy, 1854 ng/mL following), and is associated with no serious adverse events (most common adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and rash).24 Approximately 25% of patients in this trial demonstrated an increase in creatinine, with patients taking concomitant cyclosporine more affected than those on chelation therapy alone.24 For patients following HSCT or with improved hematopoiesis following immunosuppressive therapy, phlebotomy can be used to treat iron overload in lieu of chelation therapy.15

Approach to Therapy

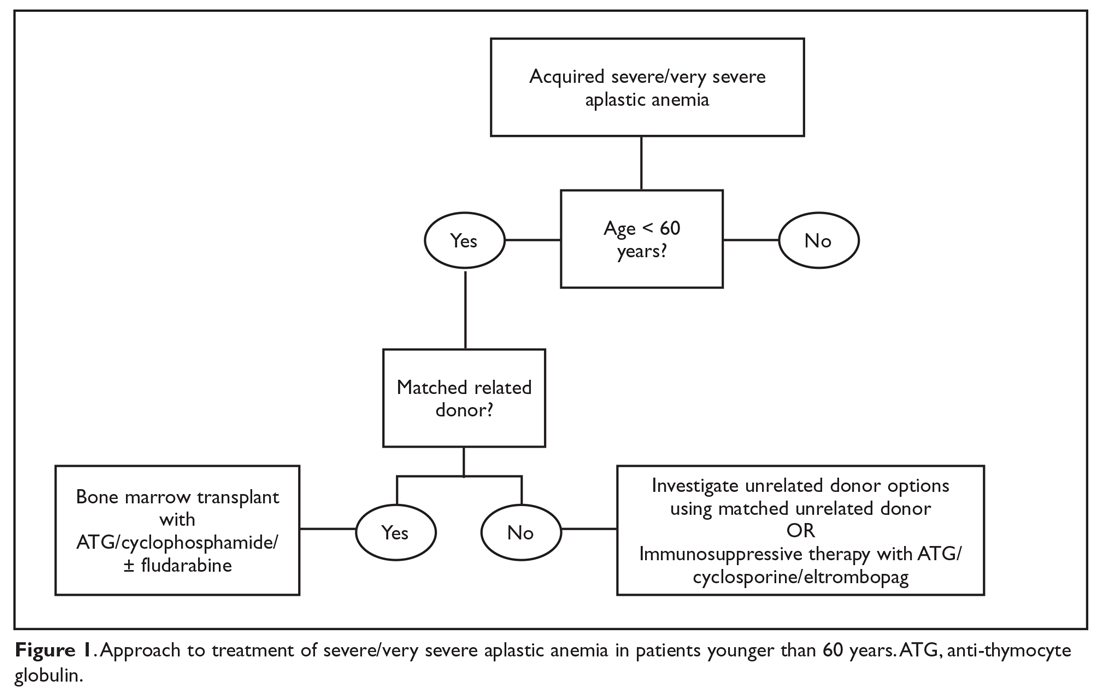

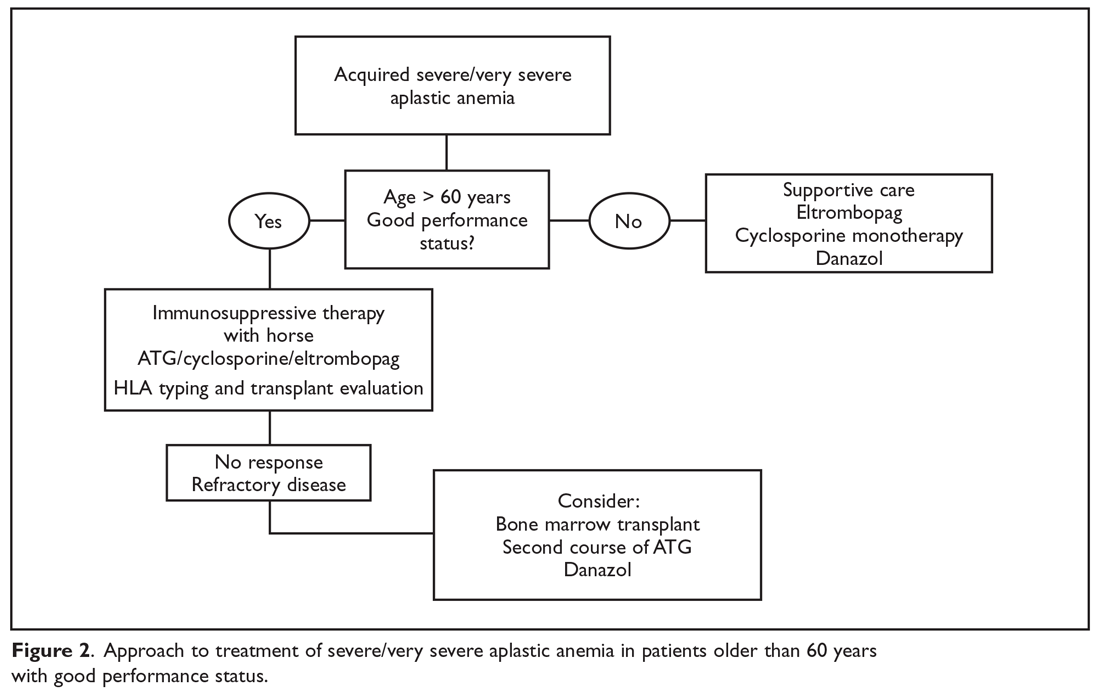

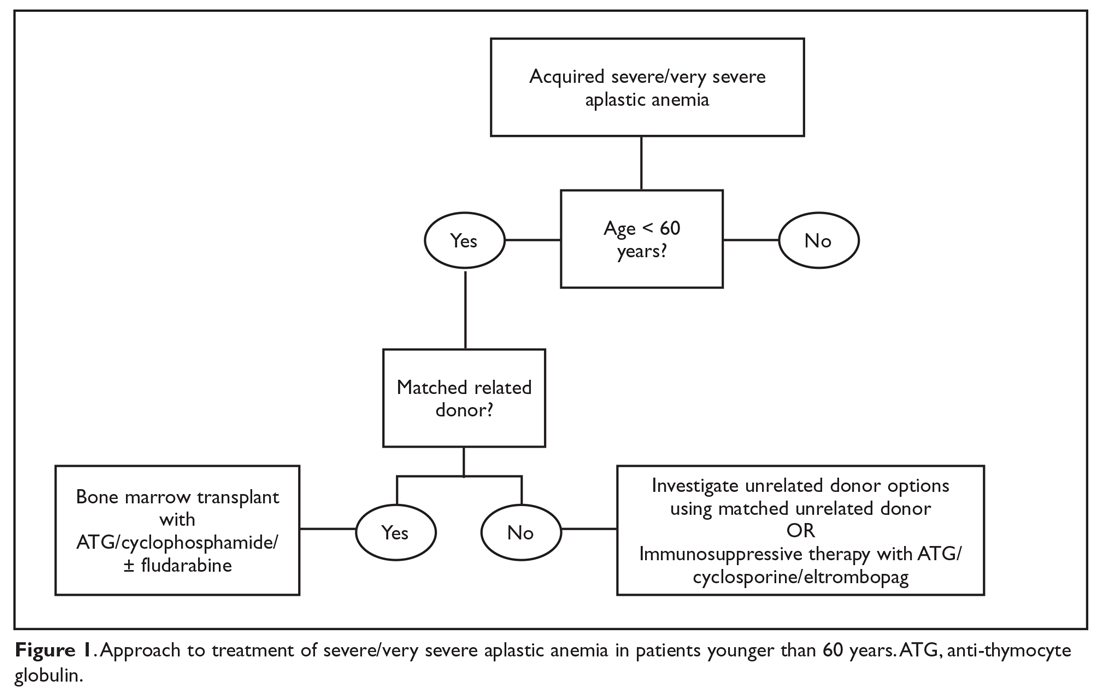

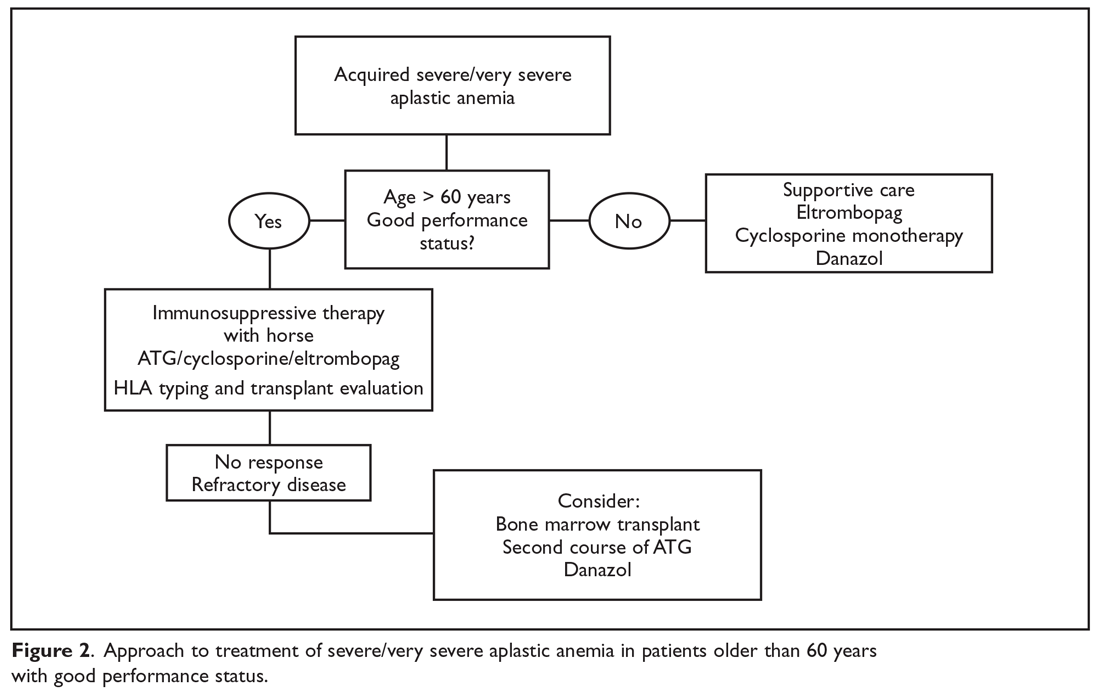

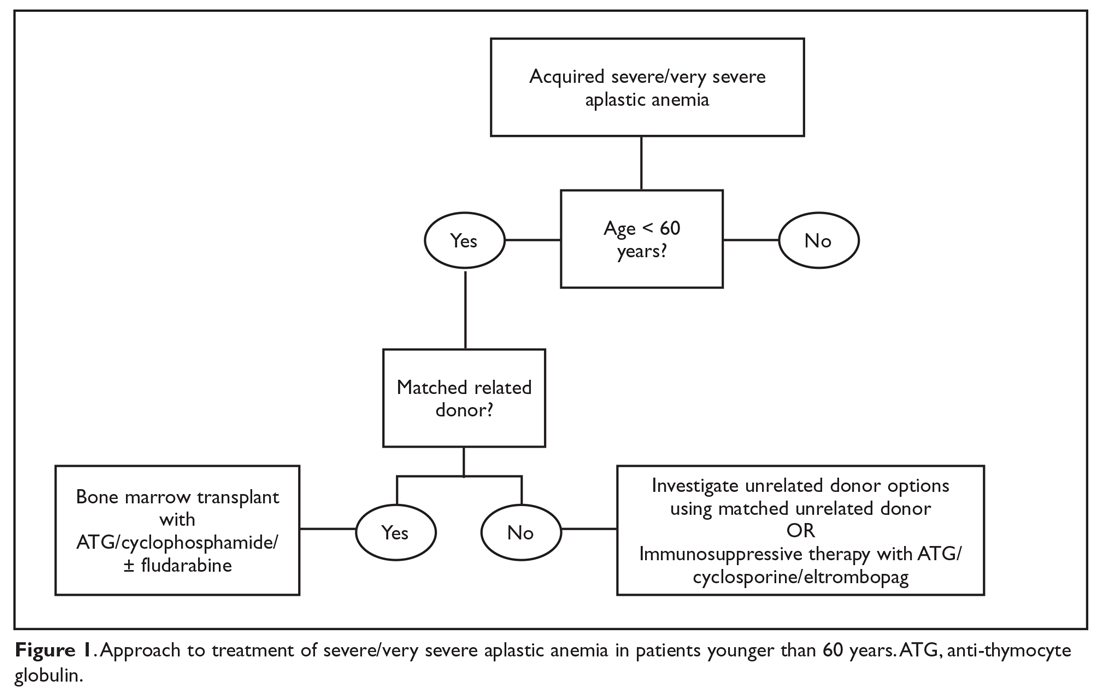

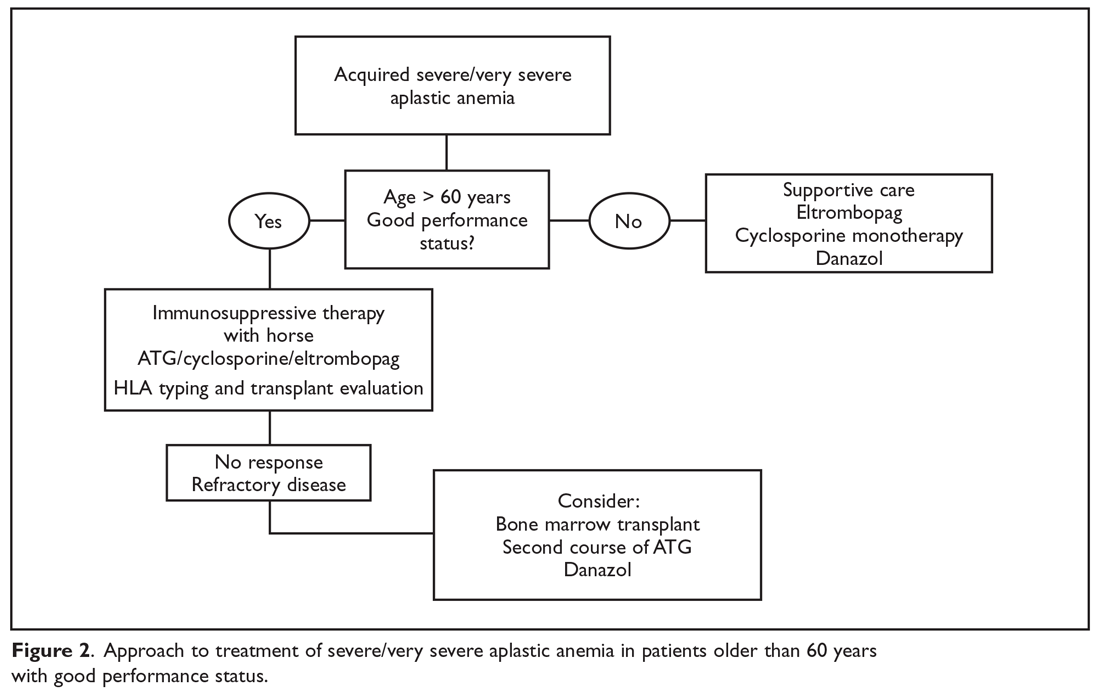

The main treatment options for SAA and VSAA include allogeneic bone marrow transplant and immunosuppression. The deciding factors as to which treatment is best initially depends on the availability of HLA-matched related donors and age (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Survival is decreased in patients with SAA or VSAA who delay initiation of therapy, and therefore prompt referral for HLA typing and evaluation for bone marrow transplant is a very important first step in managing aplastic anemia.

Matched Sibling Donor Transplant

Current standards of care recommend HLA-matched sibling donor transplant for patients with SAA or VSAA who are younger than 50 years of age, with the caveat that integration of fludarabine and reduced cyclophosphamide dosing along with ATG shows the best overall outcomes. Locasciulli and colleagues examined outcomes in patients given either immunosuppressive therapy or sibling HSCT between 1991-1996 and 1997-2002, respectively, and found that sibling HSCT was associated with a superior 10-year OS compared to immunosuppressive therapy (73% versus 68%).25 Interestingly in this study, there was no OS improvement seen with immunosuppressive therapy alone (69% versus 73%) between the 2 time periods, despite increased OS in both sibling HSCT (74% and 80%) and matched unrelated donor HSCT (38% and 65%).25 Though total body irradiation has been used in the past, it is typically not included in current conditioning regimens for matched related donor transplants.26

Current conditioning regimens typically use a combination of cyclophosphamide and ATG27,28 with or without fludarabine. Fludarabine-based conditioning regimens have shown promise in patients undergoing sibling HSCT. Maury and colleagues evaluated the role of fludarabine in addition to low-dose cyclophosphamide and ATG compared to cyclophosphamide alone or in combination with ATG in patients over age 30 undergoing sibling HSCT.9 There was a nonsignificant improvement in 5-year OS in the fludarabine arm compared to controls (77% ± 8% versus 60% ± 3%, P = 0.14) in the pooled analysis, but when adjusted for age the fludarabine arm had a significantly lower relative risk (RR) of death (RR, 0.44; P = 0.04) compared to the control arm. Shin et al reported outcomes with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/ATG, with excellent overall outcomes and no difference in patients older or younger than 40 years.29 In addition, Kim et al evaluated their experience with patients older than 40 years of age receiving matched related donors, finding comparable outcomes in those aged 41 to 50 years compared to younger patients. Outcomes did decline in those over the age of 50 years.30 Long-term data for matched related donor transplant for aplastic anemia shows excellent long-term outcomes, with minimal chronic GVHD and good performance status.31 Hence, these factors support the role of matched related donor transplant as the initial treatment in SAA and VSAA.

Regarding the role of transplant for patients who lack a matched related donor, a growing body of literature demonstrating identical outcomes between matched related and matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplants for pediatric patients32,33 supports recent recommendations for upfront unrelated donor transplantation for aplastic anemia.34,35

Immunosuppressive Therapy

For patients without an HLA-matched sibling donor or those who are older than 50 years of age, immunosuppressive therapy is the first-line therapy. ATG and cyclosporine A are the treatments of choice.36 The potential effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy in treating aplastic anemia was initially observed in patients in whom autologous transplant failed but who still experienced hematopoietic reconstitution despite the failed graft; this observation led to the hypothesis that the conditioning regimen may have an effect on hematopoiesis.16,36,37

Anti-thymocyte globulin. Immunosuppressive therapy with ATG has been used for the treatment of aplastic anemia since the 1980s.38 Historically, rabbit ATG had been used, but a 2011 study of horse ATG demonstrated superior hematological response at 6 months compared to rabbit ATG (68% versus 37%).16 Superior survival was also seen with horse ATG compared to rabbit ATG (3-year OS: 96% versus 76%). Due to these results, horse ATG is preferred over rabbit ATG. ATG should be used in combination with cyclosporine A to optimize outcomes.

Cyclosporine A. Early studies also demonstrated the efficacy of cyclosporine A in the treatment of aplastic anemia, with response rates equivalent to that of ATG monotherapy.39 Recent publications still note the efficacy of cyclosporine A in the treatment of aplastic anemia. Its role as an affordable option for single-agent therapy in developing countries is intriguing.39

The combination of the ATG and cyclosporine A was proven superior to either agent alone in a study by Frickhofen et al.37 In this study patients were randomly assigned to a control arm that received ATG plus methylprednisolone or to an arm that received ATG plus cyclosporine A and methylprednisolone. At 6 months, 70% of patients in the cyclosporine A arm had a complete remission (CR) or partial remission compared to 46% in the control arm.40 Further work confirmed the long-term efficacy of this regimen, reporting a 7-year OS of 55%.41 Among a pediatric population, immunosuppressive therapy was associated with an 83% 10-year OS.42

It is recommended that patients remain on cyclosporine therapy for a minimum of 6 months, after which a gradual taper may be considered, although there is variation among practitioners, with some continuing immunosuppressive therapy for a minimum of 12 months due to a proportion of patients being cyclosporine dependent.42,43 A study found that within a population of patients who responded to immunosuppressive therapy, 18% became cyclosporine dependent.42 The median duration of cyclosporine A treatment at full dose was 12 months, with tapering completed over a median of 19 months after patients had been in a stable CR for a minimum of 3 months. Relapse occurred more often when patients were tapered quickly (decrease ≥ 0.8 mg/kg/month) compared to slowly (0.4-0.7 mg/kg/month) or very slowly (< 0.3 mg/kg/month).

Immunosuppressive therapy plus eltrombopag. Townsley and colleagues recently investigated incorporating the use of the thrombopoietin receptor agonist eltrombopag with immunosuppressive therapy as first-line therapy in aplastic anemia.44 When given at a dose of 150 mg daily in patients aged 12 years and older or 75 mg daily in patients younger than 12 years, in conjunction with cyclosporine A and ATG, patients demonstrated markedly improved hematological response compared to historical treatment with standard immunosuppressive therapy alone.44 In the patient cohort administered eltrombopag starting on day 1 and continuing for 6 months, the complete response rate was 58%. Eltrombopag led to improvement in all cell lines among all treatment subgroups, and OS (censored for patients who proceeded to transplant) was 99% at 2 years.45 Overall, toxicities associated with this therapy were low, with liver enzyme elevations most commonly observed.44 Recently, a phase 2 trial of immunosuppressive therapy with or without eltrombopag was reported. Of the 38 patients enrolled, overall response, complete response, and time to response were not statistically different.46 With this recent finding, the role of eltrombopag in addition to immunosuppressive therapy is not clearly defined, and further studies are warranted.

OS for patients who do not respond to immunosuppressive therapy is approximately 57% at 5 years, largely due to improved supportive measures among this patient population.4,22 Therefore, it is important to recognize those patients who have a low chance of response so that second-line therapy can be pursued to improve outcomes.

Matched Unrelated Donor Transplant

For patients with refractory disease following immunosuppressive therapy who lack a matched sibling donor, MUD HSCT is considered standard therapy given the marked improvement in overall outcomes with modulating conditioning regimens and high-resolution HLA typing. A European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis comparing matched sibling HSCT to MUD HSCT noted significantly higher rates of acute grade II-IV and grade III-V GVHD (grade II-IV 13% versus 25%, grade III-IV 5% versus 10%) among patients undergoing MUD transplant.47 Chronic GVHD rates were 14% in the sibling group, as compared to 26% in the MUD group. Additional benefits seen in this analysis included improved survival when transplanted under age 20 years (84% versus 72%), when transplanted within 6 months of diagnosis (85% versus 72%), the use of ATG in the conditioning regimen (81% versus 73%), and when the donor and recipient were cytomegalovirus-negative compared to other combinations (82% versus 76%).47 Interestingly, this study demonstrated that OS was not significantly increased when using a sibling HSCT compared to a MUD HSCT, likely as a result of improved understanding of conditioning regimens, GVHD prophylaxis, and supportive care.

Additional studies of MUD HSCT have shown outcomes similar to those seen in sibling HSCT.4,43 A French study found a significant increase in survival in patients undergoing MUD HSCT compared to historical cohorts (2000-2005: OS 52%; 2006-2012: OS 74%).33 The majority of patients underwent conditioning with cyclophosphamide or a combination of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, with or without fludarabine; 81% of patients included underwent in vivo T-cell depletion, and a bone marrow donor source was utilized. OS was significantly lower in patients over age 30 years undergoing MUD HSCT (57%) compared to those under age 30 years (70%). Improved OS was also seen when patients underwent transplant within 1 year of diagnosis and when a 10/10 matched donor (compared to a 9/10 mismatched donor) was utilized.4 A 2015 study investigated the role of MUD HSCT as frontline therapy instead of immunosuppressive therapy in patients without a matched sibling donor.33 The 2-year OS was 96% in the MUD HSCT cohort compared to 91%, 94%, and 74% in historical cohorts of sibling HSCT, frontline immunosuppressive therapy, and second-line MUD HSCT following failed immunosuppressive therapy, respectively. Additionally, event-free survival in the MUD HSCT cohort (defined by the authors as death, lack of response, relapse, occurrence of clonal evolution/clinical paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, malignancies developing over follow‐up, and transplant for patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy frontline) was similar compared to sibling HSCT and superior to frontline immunosuppressive therapy and second-line MUD HSCT. Furthermore, Samarasinghe et al highlighted the importance of in vivo T-cell depletion with either ATG or alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) in the prevention of acute and chronic GVHD in both sibling HSCT and MUD HSCT.48

With continued improvement of less toxic and more immunomodulating conditioning regimens, utilization of bone marrow as a donor cell source, in vivo T-cell depletion, and use of GVHD and antimicrobial prophylaxis, more clinical evidence supports elevating MUD HSCT in the treatment plan for patients without a matched sibling donor.49 However, there is still a large population of patients without matched sibling or unrelated donor options. In an effort to expand the transplant pool and thus avoid clonal hematopoiesis, clinically significant paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and relapsed aplastic anemia, more work continues to recognize the expanding role of alternative donor transplants (cord blood and haploidentical) as another viable treatment strategy for aplastic anemia after immunosuppressive therapy failure.50

Summary

Aplastic anemia is a rare but potentially life-threatening disorder characterized by pancytopenia and a marked reduction in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Treatment should be instituted as soon as the dignosis of aplastic anemia is established. Treatment outcomes are excellent with modern supportive care and the current approach to allogeneic transplantation, and therefore referral to a bone marrow transplant program to evaluate for early transplantation is the new standard of care.

1. Peffault De Latour R, Le Rademacher J, Antin JH, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia: the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation experience.” Blood. 2013;122:4279-4286.

2. Auerbach AD. Diagnosis of Fanconi anemia by diepoxybutane analysis. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2015;85:8.7.1-17.

3. Eapen M, et al. Effect of stem cell source on outcomes after unrelated donor transplantation in severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118:2618-2621.

4. Devillier R, Dalle JH, Kulasekararaj A, et al. Unrelated alternative donor transplantation for severe acquired aplastic anemia: a study from the French Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cell Therapies and the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party of EBMT. Haematologica. 2016;101:884-890.

5. Peffault de Latour R, Peters C, Gibson B, et al. Recommendations on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes.” Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1168-1172.

6. De Medeiros CR, Zanis-Neto J, Pasquini R. Bone marrow transplantation for patients with Fanconi anemia: reduced doses of cyclophosphamide without irradiation as conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:849-852.

7. Mohanan E, Panetta JC, Lakshmi KM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fludarabine in patients with aplastic anemia and Fanconi anemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:977-983.

8 Gluckman E, Auerbach AD, Horowitz MM, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for Fanconi anemia. Blood. 1995;86:2856-2862.

9. Maury S, Bacigalupo A, Anderlini P, et al. Improved outcome of patients older than 30 years receiving HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe acquired aplastic anemia using fludarabine-based conditioning: a comparison with conventional conditioning regimen. Haematologica. 2009;94:1312-1315.

10. Talbot A, Peffault de Latour R, Raffoux E, et al. Sequential treatment for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2014;99:e199-200.

11. Ayas M, Saber W, Davies SM, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for fanconi anemia in patients with pretransplantation cytogenetic abnormalities, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1669-1676.

12. Vaht K, Göransson M, Carlson K, et al. Incidence and outcome of acquired aplastic anemia: real-world data from patients diagnosed in Sweden from 2000–2011. Haematologica. 2017;102:1683-1690.

13. Passweg JR, Marsh JC. Aplastic anemia: first-line treatment by immunosuppression and sibling marrow transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:36-42.

14. Laundy GJ, Bradley BA, Rees BM, et al. Incidence and specificity of HLA antibodies in multitransfused patients with acquired aplastic anemia. Transfusion. 2004;44:814-825.

15. Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:187-207.

16. Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, et al. Horse versus rabbit antithymocyte globulin in acquired aplastic anemia. N Eng J Med. 2011;365:430-438.

17. Höchsmann B, Moicean A, Risitano A, et al. Supportive care in severe and very severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:168-173.

18. Valdez JM, Scheinberg P, Young NS, Walsh TJ. Infections in patients with aplastic anemia. Sem Hematol. 2009;46:269-276.

19. Torres HA, Bodey GP, Rolston KV, et al. Infections in patients with aplastic anemia: experience at a tertiary care cancer center. Cancer. 2003;98:86-93.

20. Tichelli A, Schrezenmeier H, Socié G, et al. A randomized controlled study in patients with newly diagnosed severe aplastic anemia receiving antithymocyte globulin (ATG), cyclosporine, with or without G-CSF: a study of the SAA Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:4434-4441.

21. Gerson SL, Talbot GH, Hurwitz S, et al. Prolonged granulocytopenia: the major risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:345-351.

22. Valdez JM, Scheinberg P, Nunez O, et al. Decreased infection-related mortality and improved survival in severe aplastic anemia in the past two decades. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:726-735.

23. Robenshtok E, Gafter-Gvili A, Goldberg E, et al. Antifungal prophylaxis in cancer patients after chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5471-5489.

24. Lee JW, Yoon SS, Shen ZX, et al. Iron chelation therapy with deferasirox in patients with aplastic anemia: a subgroup analysis of 116 patients from the EPIC trial. Blood. 2010;116:2448-2554.

25. Locasciulli A, Oneto R, Bacigalupo A, et al. Outcome of patients with acquired aplastic anemia given first line bone marrow transplantation or immunosuppressive treatment in the last decade: a report from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2007;92:11-8.

26. Deeg HJ, Amylon MD, Harris RE, et al. Marrow transplants from unrelated donors for patients with aplastic anemia: minimum effective dose of total body irradiation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:208-215.

27. Kahl C, Leisenring W, Joachim Deeg H, et al. Cyclophosphamide and antithymocyte globulin as a conditioning regimen for allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with aplastic anaemia: a long‐term follow‐up. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:747-751.

28. Socié G. Allogeneic BM transplantation for the treatment of aplastic anemia: current results and expanding donor possibilities. ASH Education Program Book. 2013;2013:82-86.

29. Shin SH, Jeon YW, Yoon JH, et al. Comparable outcomes between younger (<40 years) and older (>40 years) adult patients with severe aplastic anemia after HLA-matched sibling stem cell transplantation using fludarabine-based conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1456-1463.

30. Kim H, Lee KH, Yoon SS, et al; Korean Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for adults over 40 years old with acquired aplastic anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1500-1508.

31. Mortensen BK, Jacobsen N, Heilmann C, Sengelov H. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia: similar long-term overall survival after transplantation with related donors compared to unrelated donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:288-290.

32. Dufour C, Svahn J, Bacigalupo A. Front-line immunosuppressive treatment of acquired aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:174-177.

33. Dufour C, Veys P, Carraro E, et al. Similar outcome of upfront-unrelated and matched sibling stem cell transplantation in idiopathic paediatric aplastic anaemia. A study on the behalf of the UK Paediatric BMT Working Party, Paediatric Diseases Working Party and Severe Aplastic Anaemia Working Party of the EBMT. Br. J Haematol. 2015;151:585-594.

34. Georges GE, Doney K, Storb R. Severe aplastic anemia: allogeneic bone marrow transplantation as first-line treatment. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2020-2028.

35. Yoshida N, Kojima S. Updated guidelines for the treatment of acquired aplastic anemia in children. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018;20:67.

36. Mathe G, Amiel JL, Schwarzenberg L, et al. Bone marrow graft in man after conditioning by antilymphocytic serum. Br Med J. 1970;2:131-136.

37. Frickhofen N, Kaltwasser JP, Schrezenmeier H, et al, German Aplastic Anemia Study Group. Treatment of aplastic anemia with antilymphocyte globulin and methylprednisolone with or without cyclosporine. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1297-1304.

38. Speck B, Gratwohl A, Nissen C, et al. Treatment of severe aplastic anaemia with antilymphocyte globulin or bone-marrow transplantation. Br Med J. 1981;282:860-863.

39. Al-Ghazaly J, Al-Dubai W, Al-Jahafi AK, et al. Cyclosporine monotherapy for severe aplastic anemia: a developing country experience. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:375-379.

40. Scheinberg P, Young NS. How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2012;120:1185-1196.

41. Rosenfeld S, Follmann D, Nunez O, Young NS. Antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine for severe aplastic anemia: association between hematologic response and long-term outcome. JAMA. 2003;289:1130-1135.

42. Saracco P, Quarello P, Iori AP, et al. Cyclosporin A response and dependence in children with acquired aplastic anaemia: a multicentre retrospective study with long‐term observation follow‐up. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:197-205.

43. Bacigalupo A. How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2017;129:1428-1436.

44. Townsley DM, Scheinberg P, Winkler T, et al. Eltrombopag added to standard immunosuppression for aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1540-1550.

45. Olnes MJ, Scheinberg P, Calvo KR, et al. Eltrombopag and improved hematopoiesis in refractory aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:11-19.

46. Assi R, Garcia-Manero G, Ravandi F, et al. Addition of eltrombopag to immunosuppressive therapy in patients with newly diagnosed aplastic anemia. Cancer. 2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31658.

47. Bacigalupo A, Socié G, Hamladji RM, et al. Current outcome of HLA identical sibling vs. unrelated donor transplants in severe aplastic anemia: an EBMT analysis. Haematologica. 2015;100:696-702.

48. Samarasinghe S, Iacobelli S, Knol C, et al. Impact of different in vivo T cell depletion strategies on outcomes following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for idiopathic aplastic anaemia: a study on behalf of the EBMT SAA Working Party. 2018Oct 17. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25314.

49. Clesham K, Dowse R, Samarasinghe S. Upfront matched unrelated donor transplantation in aplastic anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32:619-628.

50. DeZern AE, Brodsky RA. Haploidentical donor bone marrow transplantation for severe aplastic anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32:629-642.

Aplastic anemia is a rare hematologic disorder marked by pancytopenia and a hypocellular marrow. Aplastic anemia results from either inherited or acquired causes, and the treatment approach varies significantly between the 2 causes. This article reviews the treatment of inherited and acquired forms of aplastic anemia. The approach to evaluation and diagnosis of aplastic anemia is reviewed in a separate article.

Inherited Aplastic Anemia

First-line treatment options for patients with inherited marrow failure syndromes (IMFS) are androgen therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). When evaluating patients for HSCT, it is critical to identify the presence of an IMFS, as the risk and mortality associated with the conditioning regimen, stem cell source, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and secondary malignancies differ between patients with IMFS and those with acquired marrow failure syndromes or hematologic malignancies.

Potential sibling donors need to be screened for donor candidacy as well as for the inherited defect.1 Among patients with Fanconi anemia or a telomere biology disorder, the stem cell source must be considered, with bone marrow demonstrating lower rates of acute GVHD than a peripheral blood stem cell source.2-4 In IMFS patients, the donor cell type may affect the choice of conditioning regimen.5,6 Reduced-intensity conditioning in lieu of myeloablative conditioning without total body irradiation has proved feasible in patients with Fanconi anemia, and is associated with a reduced risk of secondary malignancies.5,6 Incorporation of fludarabine in the conditioning regimen of patients without a matched sibling donor is associated with superior engraftment and survival2,5,7 compared to cyclophosphamide conditioning, which was historically used in matched related donors.6,8 The addition of fludarabine appears to be especially beneficial in older patients, in whom its use is associated with lower rates of graft failure, likely due to increased immunosuppression at the time of engraftment.7,9 Fludarabine has also been incorporated into conditioning regimens for patients with a telomere biology disorder, but outcomes data is limited.5

For patients presenting with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or a high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) who are subsequently diagnosed with an IMFS, treatment can be more complex, as these patients are at high risk for toxicity from standard chemotherapy. Limited data suggests that induction therapy and transplantation are feasible in this group of patients, and this approach is associated with increased overall survival (OS) despite lower OS rates than those of IMFS patients who present prior to the development of MDS or AML.10,11 Further work is needed to determine the optimal induction regimen that balances the risks of treatment-related mortality and complications associated with conditioning regimens, risk of relapse, and risk of secondary malignancies, especially in the cohort of patients diagnosed at an older age.

Acquired Aplastic Anemia

Supportive Care

While the workup and treatment plan is being established, attention should be directed at supportive care for prevention of complications. The most common complications leading to death in patients with significant pancytopenia and neutropenia are opportunistic infections and hemorrhagic complications.12

Transfusion support is critical to avoid symptomatic anemia and hemorrhagic complications related to thrombocytopenia, which typically occur with platelet counts lower than 10,000 cells/µL. However, transfusion carries the risk of alloimmunization (which may persist for years following transfusion) and transfusion-related graft versus host disease (trGVHD), and thus use of transfusion should be minimized when possible.13,14 Transfusion support is often required to prevent complications associated with thrombocytopenia and anemia; all blood products given to patients with aplastic anemia should be irradiated and leukoreduced to reduce the risk of both alloimmunization and trGVHD. Guidelines from the British Society for Haematology recommend routine screening for Rh and Kell antibodies to reduce the risk of alloimmunization.15 Infectious complications remain a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with aplastic anemia who have prolonged neutropenia (defined as an absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 500 cells/µL).16-19 Therefore, patients should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics with antipseudomonal coverage. In a study by Tichelli and colleagues evaluating the role of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with SAA receiving immunosuppressive therapy, 55% of all patient deaths were secondary to infection.20 There was no OS benefit seen in patients who received G-CSF, though a significantly lower rate of infection was observed in the G-CSF arm compared to those not receiving G-CSF (56% versus 81%, P = 0.006).This difference was largely driven by a decrease in infectious episodes in patients with very severe aplastic anemia (VSAA) treated with G-CSF as compared to those who did not receive this therapy (22% versus 48%, P = 0.014).20

Angio-invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and Zygomycetes (eg, Rhizopus, Mucor species) remain major causes of mortality related to opportunistic mycotic infections in patients with aplastic anemia.18 The infectious risk is directly related to the duration and severity of neutropenia, with one study demonstrating a significant increase in risk in AML patients with neutropenia lasting longer than 3 weeks.21 Invasive fungal infections carry a high mortality in patients with severe neutropenia, though due to earlier recognition and empiric antifungal therapy with extended-spectrum azoles, overall mortality secondary to invasive fungal infections is declining.19,22

While neutropenia related to cytotoxic chemotherapy is commonly associated with gram-negative bacteria due to disruption of mucosal barriers, patients with aplastic anemia have an increased incidence of gram-positive bacteremia with staphylococcal species compared to other neutropenic populations.18,19 This appears to be changing with time. Valdez and colleagues demonstrated a decrease in prevalence of coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections, increased prevalence of gram-positive bacilli bacteremia, and no change in prevalence of gram-negative bacteremia in patients with aplastic anemia treated between 1989 and 2008.22 Gram-negative bacteremia caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophila, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter, and Proteus has also been reported.19 Despite a lack of clinical trials investigating the role of antifungal and antibacterial prophylaxis for patients with aplastic anemia, most centers initiate antifungal prophylaxis in patients with severe aplastic anema (SAA) or VSAA with an anti-mold agent such as voriconazole or posaconazole (which has the additional benefit compared to voriconazole of covering Mucor species).17,23 This is especially true for patients who have received ATG or undergone HSCT. For antimicrobial prophylaxis, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic with a spectrum of activity against Pseudomonas should be considered for patients with an ANC < 500 cells/µL.17 Acyclovir or valacyclovir prophylaxis is recommended for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus. Cytomegalovirus reactivation is minimal in patients with aplastic anemia, unless multiple courses of ATG are used.

Iron overload is another complication the provider must be aware of in the setting of increased transfusions in aplastic anemia patients. Lee and colleagues demonstrated that iron chelation therapy using deferasirox is effective at reducing serum ferritin levels in patients with aplastic anemia (median ferritin level: 3254 ng/mL prior to therapy, 1854 ng/mL following), and is associated with no serious adverse events (most common adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and rash).24 Approximately 25% of patients in this trial demonstrated an increase in creatinine, with patients taking concomitant cyclosporine more affected than those on chelation therapy alone.24 For patients following HSCT or with improved hematopoiesis following immunosuppressive therapy, phlebotomy can be used to treat iron overload in lieu of chelation therapy.15

Approach to Therapy

The main treatment options for SAA and VSAA include allogeneic bone marrow transplant and immunosuppression. The deciding factors as to which treatment is best initially depends on the availability of HLA-matched related donors and age (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Survival is decreased in patients with SAA or VSAA who delay initiation of therapy, and therefore prompt referral for HLA typing and evaluation for bone marrow transplant is a very important first step in managing aplastic anemia.

Matched Sibling Donor Transplant

Current standards of care recommend HLA-matched sibling donor transplant for patients with SAA or VSAA who are younger than 50 years of age, with the caveat that integration of fludarabine and reduced cyclophosphamide dosing along with ATG shows the best overall outcomes. Locasciulli and colleagues examined outcomes in patients given either immunosuppressive therapy or sibling HSCT between 1991-1996 and 1997-2002, respectively, and found that sibling HSCT was associated with a superior 10-year OS compared to immunosuppressive therapy (73% versus 68%).25 Interestingly in this study, there was no OS improvement seen with immunosuppressive therapy alone (69% versus 73%) between the 2 time periods, despite increased OS in both sibling HSCT (74% and 80%) and matched unrelated donor HSCT (38% and 65%).25 Though total body irradiation has been used in the past, it is typically not included in current conditioning regimens for matched related donor transplants.26

Current conditioning regimens typically use a combination of cyclophosphamide and ATG27,28 with or without fludarabine. Fludarabine-based conditioning regimens have shown promise in patients undergoing sibling HSCT. Maury and colleagues evaluated the role of fludarabine in addition to low-dose cyclophosphamide and ATG compared to cyclophosphamide alone or in combination with ATG in patients over age 30 undergoing sibling HSCT.9 There was a nonsignificant improvement in 5-year OS in the fludarabine arm compared to controls (77% ± 8% versus 60% ± 3%, P = 0.14) in the pooled analysis, but when adjusted for age the fludarabine arm had a significantly lower relative risk (RR) of death (RR, 0.44; P = 0.04) compared to the control arm. Shin et al reported outcomes with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/ATG, with excellent overall outcomes and no difference in patients older or younger than 40 years.29 In addition, Kim et al evaluated their experience with patients older than 40 years of age receiving matched related donors, finding comparable outcomes in those aged 41 to 50 years compared to younger patients. Outcomes did decline in those over the age of 50 years.30 Long-term data for matched related donor transplant for aplastic anemia shows excellent long-term outcomes, with minimal chronic GVHD and good performance status.31 Hence, these factors support the role of matched related donor transplant as the initial treatment in SAA and VSAA.

Regarding the role of transplant for patients who lack a matched related donor, a growing body of literature demonstrating identical outcomes between matched related and matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplants for pediatric patients32,33 supports recent recommendations for upfront unrelated donor transplantation for aplastic anemia.34,35

Immunosuppressive Therapy

For patients without an HLA-matched sibling donor or those who are older than 50 years of age, immunosuppressive therapy is the first-line therapy. ATG and cyclosporine A are the treatments of choice.36 The potential effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy in treating aplastic anemia was initially observed in patients in whom autologous transplant failed but who still experienced hematopoietic reconstitution despite the failed graft; this observation led to the hypothesis that the conditioning regimen may have an effect on hematopoiesis.16,36,37

Anti-thymocyte globulin. Immunosuppressive therapy with ATG has been used for the treatment of aplastic anemia since the 1980s.38 Historically, rabbit ATG had been used, but a 2011 study of horse ATG demonstrated superior hematological response at 6 months compared to rabbit ATG (68% versus 37%).16 Superior survival was also seen with horse ATG compared to rabbit ATG (3-year OS: 96% versus 76%). Due to these results, horse ATG is preferred over rabbit ATG. ATG should be used in combination with cyclosporine A to optimize outcomes.

Cyclosporine A. Early studies also demonstrated the efficacy of cyclosporine A in the treatment of aplastic anemia, with response rates equivalent to that of ATG monotherapy.39 Recent publications still note the efficacy of cyclosporine A in the treatment of aplastic anemia. Its role as an affordable option for single-agent therapy in developing countries is intriguing.39

The combination of the ATG and cyclosporine A was proven superior to either agent alone in a study by Frickhofen et al.37 In this study patients were randomly assigned to a control arm that received ATG plus methylprednisolone or to an arm that received ATG plus cyclosporine A and methylprednisolone. At 6 months, 70% of patients in the cyclosporine A arm had a complete remission (CR) or partial remission compared to 46% in the control arm.40 Further work confirmed the long-term efficacy of this regimen, reporting a 7-year OS of 55%.41 Among a pediatric population, immunosuppressive therapy was associated with an 83% 10-year OS.42

It is recommended that patients remain on cyclosporine therapy for a minimum of 6 months, after which a gradual taper may be considered, although there is variation among practitioners, with some continuing immunosuppressive therapy for a minimum of 12 months due to a proportion of patients being cyclosporine dependent.42,43 A study found that within a population of patients who responded to immunosuppressive therapy, 18% became cyclosporine dependent.42 The median duration of cyclosporine A treatment at full dose was 12 months, with tapering completed over a median of 19 months after patients had been in a stable CR for a minimum of 3 months. Relapse occurred more often when patients were tapered quickly (decrease ≥ 0.8 mg/kg/month) compared to slowly (0.4-0.7 mg/kg/month) or very slowly (< 0.3 mg/kg/month).

Immunosuppressive therapy plus eltrombopag. Townsley and colleagues recently investigated incorporating the use of the thrombopoietin receptor agonist eltrombopag with immunosuppressive therapy as first-line therapy in aplastic anemia.44 When given at a dose of 150 mg daily in patients aged 12 years and older or 75 mg daily in patients younger than 12 years, in conjunction with cyclosporine A and ATG, patients demonstrated markedly improved hematological response compared to historical treatment with standard immunosuppressive therapy alone.44 In the patient cohort administered eltrombopag starting on day 1 and continuing for 6 months, the complete response rate was 58%. Eltrombopag led to improvement in all cell lines among all treatment subgroups, and OS (censored for patients who proceeded to transplant) was 99% at 2 years.45 Overall, toxicities associated with this therapy were low, with liver enzyme elevations most commonly observed.44 Recently, a phase 2 trial of immunosuppressive therapy with or without eltrombopag was reported. Of the 38 patients enrolled, overall response, complete response, and time to response were not statistically different.46 With this recent finding, the role of eltrombopag in addition to immunosuppressive therapy is not clearly defined, and further studies are warranted.

OS for patients who do not respond to immunosuppressive therapy is approximately 57% at 5 years, largely due to improved supportive measures among this patient population.4,22 Therefore, it is important to recognize those patients who have a low chance of response so that second-line therapy can be pursued to improve outcomes.

Matched Unrelated Donor Transplant

For patients with refractory disease following immunosuppressive therapy who lack a matched sibling donor, MUD HSCT is considered standard therapy given the marked improvement in overall outcomes with modulating conditioning regimens and high-resolution HLA typing. A European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis comparing matched sibling HSCT to MUD HSCT noted significantly higher rates of acute grade II-IV and grade III-V GVHD (grade II-IV 13% versus 25%, grade III-IV 5% versus 10%) among patients undergoing MUD transplant.47 Chronic GVHD rates were 14% in the sibling group, as compared to 26% in the MUD group. Additional benefits seen in this analysis included improved survival when transplanted under age 20 years (84% versus 72%), when transplanted within 6 months of diagnosis (85% versus 72%), the use of ATG in the conditioning regimen (81% versus 73%), and when the donor and recipient were cytomegalovirus-negative compared to other combinations (82% versus 76%).47 Interestingly, this study demonstrated that OS was not significantly increased when using a sibling HSCT compared to a MUD HSCT, likely as a result of improved understanding of conditioning regimens, GVHD prophylaxis, and supportive care.

Additional studies of MUD HSCT have shown outcomes similar to those seen in sibling HSCT.4,43 A French study found a significant increase in survival in patients undergoing MUD HSCT compared to historical cohorts (2000-2005: OS 52%; 2006-2012: OS 74%).33 The majority of patients underwent conditioning with cyclophosphamide or a combination of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, with or without fludarabine; 81% of patients included underwent in vivo T-cell depletion, and a bone marrow donor source was utilized. OS was significantly lower in patients over age 30 years undergoing MUD HSCT (57%) compared to those under age 30 years (70%). Improved OS was also seen when patients underwent transplant within 1 year of diagnosis and when a 10/10 matched donor (compared to a 9/10 mismatched donor) was utilized.4 A 2015 study investigated the role of MUD HSCT as frontline therapy instead of immunosuppressive therapy in patients without a matched sibling donor.33 The 2-year OS was 96% in the MUD HSCT cohort compared to 91%, 94%, and 74% in historical cohorts of sibling HSCT, frontline immunosuppressive therapy, and second-line MUD HSCT following failed immunosuppressive therapy, respectively. Additionally, event-free survival in the MUD HSCT cohort (defined by the authors as death, lack of response, relapse, occurrence of clonal evolution/clinical paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, malignancies developing over follow‐up, and transplant for patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy frontline) was similar compared to sibling HSCT and superior to frontline immunosuppressive therapy and second-line MUD HSCT. Furthermore, Samarasinghe et al highlighted the importance of in vivo T-cell depletion with either ATG or alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) in the prevention of acute and chronic GVHD in both sibling HSCT and MUD HSCT.48

With continued improvement of less toxic and more immunomodulating conditioning regimens, utilization of bone marrow as a donor cell source, in vivo T-cell depletion, and use of GVHD and antimicrobial prophylaxis, more clinical evidence supports elevating MUD HSCT in the treatment plan for patients without a matched sibling donor.49 However, there is still a large population of patients without matched sibling or unrelated donor options. In an effort to expand the transplant pool and thus avoid clonal hematopoiesis, clinically significant paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and relapsed aplastic anemia, more work continues to recognize the expanding role of alternative donor transplants (cord blood and haploidentical) as another viable treatment strategy for aplastic anemia after immunosuppressive therapy failure.50

Summary

Aplastic anemia is a rare but potentially life-threatening disorder characterized by pancytopenia and a marked reduction in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Treatment should be instituted as soon as the dignosis of aplastic anemia is established. Treatment outcomes are excellent with modern supportive care and the current approach to allogeneic transplantation, and therefore referral to a bone marrow transplant program to evaluate for early transplantation is the new standard of care.

Aplastic anemia is a rare hematologic disorder marked by pancytopenia and a hypocellular marrow. Aplastic anemia results from either inherited or acquired causes, and the treatment approach varies significantly between the 2 causes. This article reviews the treatment of inherited and acquired forms of aplastic anemia. The approach to evaluation and diagnosis of aplastic anemia is reviewed in a separate article.

Inherited Aplastic Anemia

First-line treatment options for patients with inherited marrow failure syndromes (IMFS) are androgen therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). When evaluating patients for HSCT, it is critical to identify the presence of an IMFS, as the risk and mortality associated with the conditioning regimen, stem cell source, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and secondary malignancies differ between patients with IMFS and those with acquired marrow failure syndromes or hematologic malignancies.

Potential sibling donors need to be screened for donor candidacy as well as for the inherited defect.1 Among patients with Fanconi anemia or a telomere biology disorder, the stem cell source must be considered, with bone marrow demonstrating lower rates of acute GVHD than a peripheral blood stem cell source.2-4 In IMFS patients, the donor cell type may affect the choice of conditioning regimen.5,6 Reduced-intensity conditioning in lieu of myeloablative conditioning without total body irradiation has proved feasible in patients with Fanconi anemia, and is associated with a reduced risk of secondary malignancies.5,6 Incorporation of fludarabine in the conditioning regimen of patients without a matched sibling donor is associated with superior engraftment and survival2,5,7 compared to cyclophosphamide conditioning, which was historically used in matched related donors.6,8 The addition of fludarabine appears to be especially beneficial in older patients, in whom its use is associated with lower rates of graft failure, likely due to increased immunosuppression at the time of engraftment.7,9 Fludarabine has also been incorporated into conditioning regimens for patients with a telomere biology disorder, but outcomes data is limited.5

For patients presenting with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or a high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) who are subsequently diagnosed with an IMFS, treatment can be more complex, as these patients are at high risk for toxicity from standard chemotherapy. Limited data suggests that induction therapy and transplantation are feasible in this group of patients, and this approach is associated with increased overall survival (OS) despite lower OS rates than those of IMFS patients who present prior to the development of MDS or AML.10,11 Further work is needed to determine the optimal induction regimen that balances the risks of treatment-related mortality and complications associated with conditioning regimens, risk of relapse, and risk of secondary malignancies, especially in the cohort of patients diagnosed at an older age.

Acquired Aplastic Anemia

Supportive Care

While the workup and treatment plan is being established, attention should be directed at supportive care for prevention of complications. The most common complications leading to death in patients with significant pancytopenia and neutropenia are opportunistic infections and hemorrhagic complications.12

Transfusion support is critical to avoid symptomatic anemia and hemorrhagic complications related to thrombocytopenia, which typically occur with platelet counts lower than 10,000 cells/µL. However, transfusion carries the risk of alloimmunization (which may persist for years following transfusion) and transfusion-related graft versus host disease (trGVHD), and thus use of transfusion should be minimized when possible.13,14 Transfusion support is often required to prevent complications associated with thrombocytopenia and anemia; all blood products given to patients with aplastic anemia should be irradiated and leukoreduced to reduce the risk of both alloimmunization and trGVHD. Guidelines from the British Society for Haematology recommend routine screening for Rh and Kell antibodies to reduce the risk of alloimmunization.15 Infectious complications remain a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with aplastic anemia who have prolonged neutropenia (defined as an absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 500 cells/µL).16-19 Therefore, patients should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics with antipseudomonal coverage. In a study by Tichelli and colleagues evaluating the role of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with SAA receiving immunosuppressive therapy, 55% of all patient deaths were secondary to infection.20 There was no OS benefit seen in patients who received G-CSF, though a significantly lower rate of infection was observed in the G-CSF arm compared to those not receiving G-CSF (56% versus 81%, P = 0.006).This difference was largely driven by a decrease in infectious episodes in patients with very severe aplastic anemia (VSAA) treated with G-CSF as compared to those who did not receive this therapy (22% versus 48%, P = 0.014).20

Angio-invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and Zygomycetes (eg, Rhizopus, Mucor species) remain major causes of mortality related to opportunistic mycotic infections in patients with aplastic anemia.18 The infectious risk is directly related to the duration and severity of neutropenia, with one study demonstrating a significant increase in risk in AML patients with neutropenia lasting longer than 3 weeks.21 Invasive fungal infections carry a high mortality in patients with severe neutropenia, though due to earlier recognition and empiric antifungal therapy with extended-spectrum azoles, overall mortality secondary to invasive fungal infections is declining.19,22

While neutropenia related to cytotoxic chemotherapy is commonly associated with gram-negative bacteria due to disruption of mucosal barriers, patients with aplastic anemia have an increased incidence of gram-positive bacteremia with staphylococcal species compared to other neutropenic populations.18,19 This appears to be changing with time. Valdez and colleagues demonstrated a decrease in prevalence of coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections, increased prevalence of gram-positive bacilli bacteremia, and no change in prevalence of gram-negative bacteremia in patients with aplastic anemia treated between 1989 and 2008.22 Gram-negative bacteremia caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophila, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter, and Proteus has also been reported.19 Despite a lack of clinical trials investigating the role of antifungal and antibacterial prophylaxis for patients with aplastic anemia, most centers initiate antifungal prophylaxis in patients with severe aplastic anema (SAA) or VSAA with an anti-mold agent such as voriconazole or posaconazole (which has the additional benefit compared to voriconazole of covering Mucor species).17,23 This is especially true for patients who have received ATG or undergone HSCT. For antimicrobial prophylaxis, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic with a spectrum of activity against Pseudomonas should be considered for patients with an ANC < 500 cells/µL.17 Acyclovir or valacyclovir prophylaxis is recommended for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus. Cytomegalovirus reactivation is minimal in patients with aplastic anemia, unless multiple courses of ATG are used.

Iron overload is another complication the provider must be aware of in the setting of increased transfusions in aplastic anemia patients. Lee and colleagues demonstrated that iron chelation therapy using deferasirox is effective at reducing serum ferritin levels in patients with aplastic anemia (median ferritin level: 3254 ng/mL prior to therapy, 1854 ng/mL following), and is associated with no serious adverse events (most common adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and rash).24 Approximately 25% of patients in this trial demonstrated an increase in creatinine, with patients taking concomitant cyclosporine more affected than those on chelation therapy alone.24 For patients following HSCT or with improved hematopoiesis following immunosuppressive therapy, phlebotomy can be used to treat iron overload in lieu of chelation therapy.15

Approach to Therapy

The main treatment options for SAA and VSAA include allogeneic bone marrow transplant and immunosuppression. The deciding factors as to which treatment is best initially depends on the availability of HLA-matched related donors and age (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Survival is decreased in patients with SAA or VSAA who delay initiation of therapy, and therefore prompt referral for HLA typing and evaluation for bone marrow transplant is a very important first step in managing aplastic anemia.

Matched Sibling Donor Transplant

Current standards of care recommend HLA-matched sibling donor transplant for patients with SAA or VSAA who are younger than 50 years of age, with the caveat that integration of fludarabine and reduced cyclophosphamide dosing along with ATG shows the best overall outcomes. Locasciulli and colleagues examined outcomes in patients given either immunosuppressive therapy or sibling HSCT between 1991-1996 and 1997-2002, respectively, and found that sibling HSCT was associated with a superior 10-year OS compared to immunosuppressive therapy (73% versus 68%).25 Interestingly in this study, there was no OS improvement seen with immunosuppressive therapy alone (69% versus 73%) between the 2 time periods, despite increased OS in both sibling HSCT (74% and 80%) and matched unrelated donor HSCT (38% and 65%).25 Though total body irradiation has been used in the past, it is typically not included in current conditioning regimens for matched related donor transplants.26

Current conditioning regimens typically use a combination of cyclophosphamide and ATG27,28 with or without fludarabine. Fludarabine-based conditioning regimens have shown promise in patients undergoing sibling HSCT. Maury and colleagues evaluated the role of fludarabine in addition to low-dose cyclophosphamide and ATG compared to cyclophosphamide alone or in combination with ATG in patients over age 30 undergoing sibling HSCT.9 There was a nonsignificant improvement in 5-year OS in the fludarabine arm compared to controls (77% ± 8% versus 60% ± 3%, P = 0.14) in the pooled analysis, but when adjusted for age the fludarabine arm had a significantly lower relative risk (RR) of death (RR, 0.44; P = 0.04) compared to the control arm. Shin et al reported outcomes with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/ATG, with excellent overall outcomes and no difference in patients older or younger than 40 years.29 In addition, Kim et al evaluated their experience with patients older than 40 years of age receiving matched related donors, finding comparable outcomes in those aged 41 to 50 years compared to younger patients. Outcomes did decline in those over the age of 50 years.30 Long-term data for matched related donor transplant for aplastic anemia shows excellent long-term outcomes, with minimal chronic GVHD and good performance status.31 Hence, these factors support the role of matched related donor transplant as the initial treatment in SAA and VSAA.

Regarding the role of transplant for patients who lack a matched related donor, a growing body of literature demonstrating identical outcomes between matched related and matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplants for pediatric patients32,33 supports recent recommendations for upfront unrelated donor transplantation for aplastic anemia.34,35

Immunosuppressive Therapy

For patients without an HLA-matched sibling donor or those who are older than 50 years of age, immunosuppressive therapy is the first-line therapy. ATG and cyclosporine A are the treatments of choice.36 The potential effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy in treating aplastic anemia was initially observed in patients in whom autologous transplant failed but who still experienced hematopoietic reconstitution despite the failed graft; this observation led to the hypothesis that the conditioning regimen may have an effect on hematopoiesis.16,36,37

Anti-thymocyte globulin. Immunosuppressive therapy with ATG has been used for the treatment of aplastic anemia since the 1980s.38 Historically, rabbit ATG had been used, but a 2011 study of horse ATG demonstrated superior hematological response at 6 months compared to rabbit ATG (68% versus 37%).16 Superior survival was also seen with horse ATG compared to rabbit ATG (3-year OS: 96% versus 76%). Due to these results, horse ATG is preferred over rabbit ATG. ATG should be used in combination with cyclosporine A to optimize outcomes.

Cyclosporine A. Early studies also demonstrated the efficacy of cyclosporine A in the treatment of aplastic anemia, with response rates equivalent to that of ATG monotherapy.39 Recent publications still note the efficacy of cyclosporine A in the treatment of aplastic anemia. Its role as an affordable option for single-agent therapy in developing countries is intriguing.39

The combination of the ATG and cyclosporine A was proven superior to either agent alone in a study by Frickhofen et al.37 In this study patients were randomly assigned to a control arm that received ATG plus methylprednisolone or to an arm that received ATG plus cyclosporine A and methylprednisolone. At 6 months, 70% of patients in the cyclosporine A arm had a complete remission (CR) or partial remission compared to 46% in the control arm.40 Further work confirmed the long-term efficacy of this regimen, reporting a 7-year OS of 55%.41 Among a pediatric population, immunosuppressive therapy was associated with an 83% 10-year OS.42

It is recommended that patients remain on cyclosporine therapy for a minimum of 6 months, after which a gradual taper may be considered, although there is variation among practitioners, with some continuing immunosuppressive therapy for a minimum of 12 months due to a proportion of patients being cyclosporine dependent.42,43 A study found that within a population of patients who responded to immunosuppressive therapy, 18% became cyclosporine dependent.42 The median duration of cyclosporine A treatment at full dose was 12 months, with tapering completed over a median of 19 months after patients had been in a stable CR for a minimum of 3 months. Relapse occurred more often when patients were tapered quickly (decrease ≥ 0.8 mg/kg/month) compared to slowly (0.4-0.7 mg/kg/month) or very slowly (< 0.3 mg/kg/month).

Immunosuppressive therapy plus eltrombopag. Townsley and colleagues recently investigated incorporating the use of the thrombopoietin receptor agonist eltrombopag with immunosuppressive therapy as first-line therapy in aplastic anemia.44 When given at a dose of 150 mg daily in patients aged 12 years and older or 75 mg daily in patients younger than 12 years, in conjunction with cyclosporine A and ATG, patients demonstrated markedly improved hematological response compared to historical treatment with standard immunosuppressive therapy alone.44 In the patient cohort administered eltrombopag starting on day 1 and continuing for 6 months, the complete response rate was 58%. Eltrombopag led to improvement in all cell lines among all treatment subgroups, and OS (censored for patients who proceeded to transplant) was 99% at 2 years.45 Overall, toxicities associated with this therapy were low, with liver enzyme elevations most commonly observed.44 Recently, a phase 2 trial of immunosuppressive therapy with or without eltrombopag was reported. Of the 38 patients enrolled, overall response, complete response, and time to response were not statistically different.46 With this recent finding, the role of eltrombopag in addition to immunosuppressive therapy is not clearly defined, and further studies are warranted.

OS for patients who do not respond to immunosuppressive therapy is approximately 57% at 5 years, largely due to improved supportive measures among this patient population.4,22 Therefore, it is important to recognize those patients who have a low chance of response so that second-line therapy can be pursued to improve outcomes.

Matched Unrelated Donor Transplant

For patients with refractory disease following immunosuppressive therapy who lack a matched sibling donor, MUD HSCT is considered standard therapy given the marked improvement in overall outcomes with modulating conditioning regimens and high-resolution HLA typing. A European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis comparing matched sibling HSCT to MUD HSCT noted significantly higher rates of acute grade II-IV and grade III-V GVHD (grade II-IV 13% versus 25%, grade III-IV 5% versus 10%) among patients undergoing MUD transplant.47 Chronic GVHD rates were 14% in the sibling group, as compared to 26% in the MUD group. Additional benefits seen in this analysis included improved survival when transplanted under age 20 years (84% versus 72%), when transplanted within 6 months of diagnosis (85% versus 72%), the use of ATG in the conditioning regimen (81% versus 73%), and when the donor and recipient were cytomegalovirus-negative compared to other combinations (82% versus 76%).47 Interestingly, this study demonstrated that OS was not significantly increased when using a sibling HSCT compared to a MUD HSCT, likely as a result of improved understanding of conditioning regimens, GVHD prophylaxis, and supportive care.

Additional studies of MUD HSCT have shown outcomes similar to those seen in sibling HSCT.4,43 A French study found a significant increase in survival in patients undergoing MUD HSCT compared to historical cohorts (2000-2005: OS 52%; 2006-2012: OS 74%).33 The majority of patients underwent conditioning with cyclophosphamide or a combination of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, with or without fludarabine; 81% of patients included underwent in vivo T-cell depletion, and a bone marrow donor source was utilized. OS was significantly lower in patients over age 30 years undergoing MUD HSCT (57%) compared to those under age 30 years (70%). Improved OS was also seen when patients underwent transplant within 1 year of diagnosis and when a 10/10 matched donor (compared to a 9/10 mismatched donor) was utilized.4 A 2015 study investigated the role of MUD HSCT as frontline therapy instead of immunosuppressive therapy in patients without a matched sibling donor.33 The 2-year OS was 96% in the MUD HSCT cohort compared to 91%, 94%, and 74% in historical cohorts of sibling HSCT, frontline immunosuppressive therapy, and second-line MUD HSCT following failed immunosuppressive therapy, respectively. Additionally, event-free survival in the MUD HSCT cohort (defined by the authors as death, lack of response, relapse, occurrence of clonal evolution/clinical paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, malignancies developing over follow‐up, and transplant for patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy frontline) was similar compared to sibling HSCT and superior to frontline immunosuppressive therapy and second-line MUD HSCT. Furthermore, Samarasinghe et al highlighted the importance of in vivo T-cell depletion with either ATG or alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) in the prevention of acute and chronic GVHD in both sibling HSCT and MUD HSCT.48

With continued improvement of less toxic and more immunomodulating conditioning regimens, utilization of bone marrow as a donor cell source, in vivo T-cell depletion, and use of GVHD and antimicrobial prophylaxis, more clinical evidence supports elevating MUD HSCT in the treatment plan for patients without a matched sibling donor.49 However, there is still a large population of patients without matched sibling or unrelated donor options. In an effort to expand the transplant pool and thus avoid clonal hematopoiesis, clinically significant paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and relapsed aplastic anemia, more work continues to recognize the expanding role of alternative donor transplants (cord blood and haploidentical) as another viable treatment strategy for aplastic anemia after immunosuppressive therapy failure.50

Summary

Aplastic anemia is a rare but potentially life-threatening disorder characterized by pancytopenia and a marked reduction in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Treatment should be instituted as soon as the dignosis of aplastic anemia is established. Treatment outcomes are excellent with modern supportive care and the current approach to allogeneic transplantation, and therefore referral to a bone marrow transplant program to evaluate for early transplantation is the new standard of care.

1. Peffault De Latour R, Le Rademacher J, Antin JH, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia: the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation experience.” Blood. 2013;122:4279-4286.

2. Auerbach AD. Diagnosis of Fanconi anemia by diepoxybutane analysis. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2015;85:8.7.1-17.

3. Eapen M, et al. Effect of stem cell source on outcomes after unrelated donor transplantation in severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118:2618-2621.

4. Devillier R, Dalle JH, Kulasekararaj A, et al. Unrelated alternative donor transplantation for severe acquired aplastic anemia: a study from the French Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cell Therapies and the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party of EBMT. Haematologica. 2016;101:884-890.

5. Peffault de Latour R, Peters C, Gibson B, et al. Recommendations on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes.” Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1168-1172.

6. De Medeiros CR, Zanis-Neto J, Pasquini R. Bone marrow transplantation for patients with Fanconi anemia: reduced doses of cyclophosphamide without irradiation as conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:849-852.

7. Mohanan E, Panetta JC, Lakshmi KM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fludarabine in patients with aplastic anemia and Fanconi anemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:977-983.

8 Gluckman E, Auerbach AD, Horowitz MM, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for Fanconi anemia. Blood. 1995;86:2856-2862.

9. Maury S, Bacigalupo A, Anderlini P, et al. Improved outcome of patients older than 30 years receiving HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe acquired aplastic anemia using fludarabine-based conditioning: a comparison with conventional conditioning regimen. Haematologica. 2009;94:1312-1315.

10. Talbot A, Peffault de Latour R, Raffoux E, et al. Sequential treatment for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2014;99:e199-200.

11. Ayas M, Saber W, Davies SM, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for fanconi anemia in patients with pretransplantation cytogenetic abnormalities, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1669-1676.

12. Vaht K, Göransson M, Carlson K, et al. Incidence and outcome of acquired aplastic anemia: real-world data from patients diagnosed in Sweden from 2000–2011. Haematologica. 2017;102:1683-1690.

13. Passweg JR, Marsh JC. Aplastic anemia: first-line treatment by immunosuppression and sibling marrow transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:36-42.

14. Laundy GJ, Bradley BA, Rees BM, et al. Incidence and specificity of HLA antibodies in multitransfused patients with acquired aplastic anemia. Transfusion. 2004;44:814-825.

15. Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:187-207.

16. Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, et al. Horse versus rabbit antithymocyte globulin in acquired aplastic anemia. N Eng J Med. 2011;365:430-438.

17. Höchsmann B, Moicean A, Risitano A, et al. Supportive care in severe and very severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:168-173.

18. Valdez JM, Scheinberg P, Young NS, Walsh TJ. Infections in patients with aplastic anemia. Sem Hematol. 2009;46:269-276.

19. Torres HA, Bodey GP, Rolston KV, et al. Infections in patients with aplastic anemia: experience at a tertiary care cancer center. Cancer. 2003;98:86-93.

20. Tichelli A, Schrezenmeier H, Socié G, et al. A randomized controlled study in patients with newly diagnosed severe aplastic anemia receiving antithymocyte globulin (ATG), cyclosporine, with or without G-CSF: a study of the SAA Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:4434-4441.

21. Gerson SL, Talbot GH, Hurwitz S, et al. Prolonged granulocytopenia: the major risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:345-351.

22. Valdez JM, Scheinberg P, Nunez O, et al. Decreased infection-related mortality and improved survival in severe aplastic anemia in the past two decades. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:726-735.

23. Robenshtok E, Gafter-Gvili A, Goldberg E, et al. Antifungal prophylaxis in cancer patients after chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5471-5489.

24. Lee JW, Yoon SS, Shen ZX, et al. Iron chelation therapy with deferasirox in patients with aplastic anemia: a subgroup analysis of 116 patients from the EPIC trial. Blood. 2010;116:2448-2554.

25. Locasciulli A, Oneto R, Bacigalupo A, et al. Outcome of patients with acquired aplastic anemia given first line bone marrow transplantation or immunosuppressive treatment in the last decade: a report from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2007;92:11-8.

26. Deeg HJ, Amylon MD, Harris RE, et al. Marrow transplants from unrelated donors for patients with aplastic anemia: minimum effective dose of total body irradiation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:208-215.

27. Kahl C, Leisenring W, Joachim Deeg H, et al. Cyclophosphamide and antithymocyte globulin as a conditioning regimen for allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with aplastic anaemia: a long‐term follow‐up. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:747-751.

28. Socié G. Allogeneic BM transplantation for the treatment of aplastic anemia: current results and expanding donor possibilities. ASH Education Program Book. 2013;2013:82-86.

29. Shin SH, Jeon YW, Yoon JH, et al. Comparable outcomes between younger (<40 years) and older (>40 years) adult patients with severe aplastic anemia after HLA-matched sibling stem cell transplantation using fludarabine-based conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1456-1463.

30. Kim H, Lee KH, Yoon SS, et al; Korean Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for adults over 40 years old with acquired aplastic anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1500-1508.

31. Mortensen BK, Jacobsen N, Heilmann C, Sengelov H. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia: similar long-term overall survival after transplantation with related donors compared to unrelated donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:288-290.

32. Dufour C, Svahn J, Bacigalupo A. Front-line immunosuppressive treatment of acquired aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:174-177.