User login

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

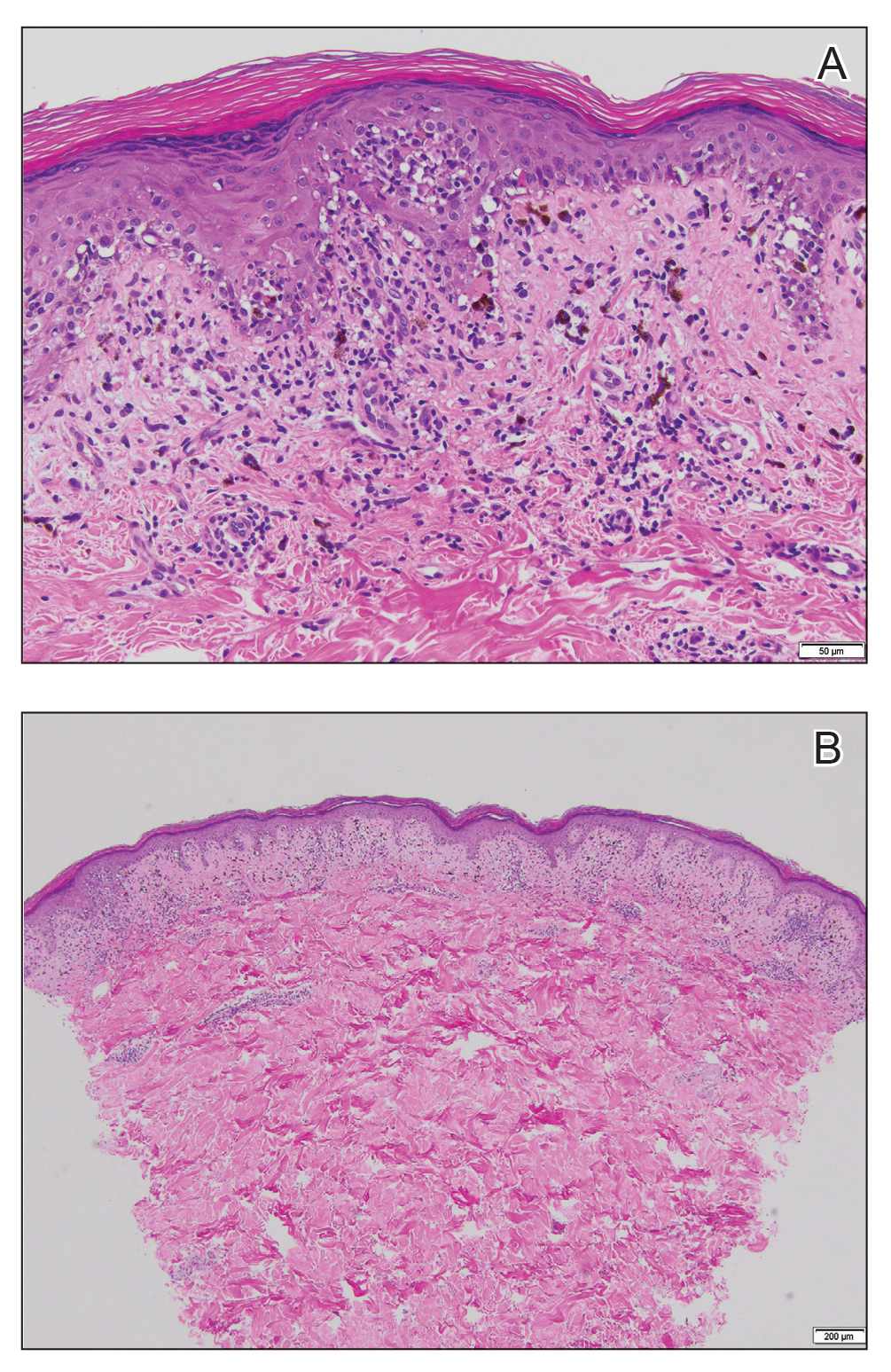

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

A 45-year-old African American woman presented with an asymptomatic rash that had worsened over the month prior to presentation. It initially began on the upper thighs and then spread to the abdomen, groin, and buttocks. The rash was mildly pruritic and had grown both in size and number of lesions. She had not tried any new over-the-counter medications. Her medical history was notable for late-stage breast cancer diagnosed 4 years prior that was treated with radiation and neoadjuvant NeoPACT—carboplatin, docetaxel, and pembrolizumab. One year prior to presentation, she underwent a lumpectomy that was complicated by gas gangrene of the finger. She has been in remission since the surgery. Physical examination at the current presentation was remarkable for multiple well-circumscribed, hyperpigmented macules on the medial thighs, lower abdomen, and buttocks. Syphilis antibody screening was negative.