User login

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

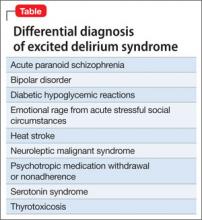

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.