User login

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

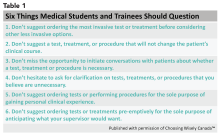

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.