User login

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to screen for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and lower urinary tract symptoms, to perform the initial diagnostic workup, and to start medical therapy in uncomplicated cases. Effective medical therapy is available but underutilized in the primary care setting.1

This overview covers how to identify and evaluate patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, initiate therapy, and identify factors warranting timely urology referral.

TWO MECHANISMS: STATIC, DYNAMIC

BPH is a histologic diagnosis of proliferation of smooth muscle, epithelium, and stromal cells within the transition zone of the prostate,2 which surrounds the proximal urethra.

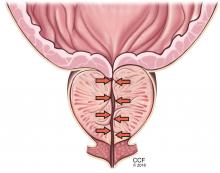

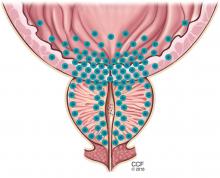

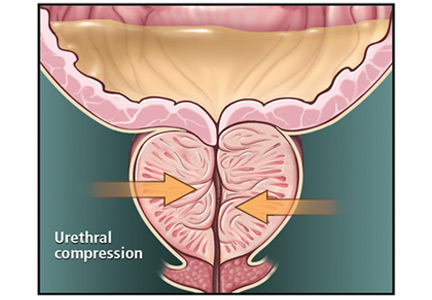

Symptoms arise through two mechanisms: static, in which the hyperplastic prostatic tissue compresses the urethra (Figure 1); and dynamic, with increased adrenergic nervous system and prostatic smooth muscle tone (Figure 2).3 Both mechanisms increase resistance to urinary flow at the level of the bladder outlet.

As an adaptive change to overcome outlet resistance and maintain urinary flow, the detrusor muscles undergo hypertrophy. However, over time the bladder may develop diminished compliance and increased detrusor activity, causing symptoms such as urinary frequency and urgency. Chronic bladder outlet obstruction can lead to bladder decompensation and detrusor underactivity, manifesting as incomplete emptying, urinary hesitancy, intermittency (starting and stopping while voiding), a weakened urinary stream, and urinary retention.

MOST MEN EVENTUALLY DEVELOP BPH

Autopsy studies have shown that BPH increases in prevalence with age beginning around age 30 and reaching a peak prevalence of 88% in men in their 80s.4 This trend parallels those of the incidence and severity of lower urinary tract symptoms.5

In the year 2000 alone, BPH was responsible for 4.5 million physician visits at an estimated direct cost of $1.1 billion, not including the cost of pharmacotherapy.6

OFFICE WORKUP

BPH can cause lower urinary tract symptoms that fall into two categories: storage and emptying. Storage symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia, whereas emptying symptoms include weak stream, hesitancy, intermittency, incomplete emptying, straining, and postvoid dribbling.

History and differential diagnosis

Assessment begins with characterizing the patient’s symptoms and determining those that are most bothersome. Because BPH is just one of many possible causes of lower urinary tract symptoms, a detailed medical history is necessary to evaluate for other conditions that may cause lower urinary tract dysfunction or complicate its treatment.

Obstructive urinary symptoms can arise from BPH or from other conditions, including urethral stricture disease and neurogenic voiding dysfunction.

Irritative voiding symptoms such as urinary urgency and frequency can result from detrusor overactivity secondary to BPH, but can also be caused by neurologic disease, malignancy, initiation of diuretic therapy, high fluid intake, or consumption of bladder irritants such as caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods.

Urinary frequency is sometimes a presenting symptom of undiagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus resulting from glucosuria and polyuria. Iatrogenic causes of polyuria include the new hypoglycemic agents canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, which block renal glucose reabsorption, improving glycemic control by inducing urinary

glucose loss.7

Nocturia has many possible nonurologic causes including heart failure (in which excess extravascular fluid shifts to the intravascular space when the patient lies down, resulting in polyuria), obstructive sleep apnea, and behavioral factors such as high evening fluid intake. In these cases, patients usually have nocturnal polyuria (greater than one-third of 24-hour urine output at night) rather than only nocturia (waking at night to void). A fluid diary is a simple tool that can differentiate these two conditions.

Hematuria can develop in patients with BPH with bleeding from congested prostatic or bladder neck vessels; however, hematuria may indicate an underlying malignancy or urolithiasis, for which a urologic workup is indicated.

The broad differential diagnosis for the different lower urinary tract symptoms highlights the importance of obtaining a thorough history.

Physical examination

A general examination should include the following:

Body mass index. Obese patients are at risk of obstructive sleep apnea, which can cause nocturnal polyuria.

Gait. Abnormal gait may suggest a neurologic condition such as Parkinson disease or stroke that can also affect lower urinary tract function.

Lower abdomen. A palpable bladder suggests urinary retention.

External genitalia. Penile causes of urinary obstruction include urethral meatal stenosis or a palpable urethral mass.

Digital rectal examination can reveal benign prostatic enlargement or nodules or firmness, which suggest malignancy and warrant urologic referral.

Neurologic examination, including evaluation of anal sphincter tone and lower extremity sensorimotor function.

Feet. Bilateral lower-extremity edema may be due to heart failure or venous insufficiency.

The International Prostate Symptom Score

All men with lower urinary tract symptoms should complete the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) survey, consisting of seven questions about urinary symptoms plus one about quality of life.8 Specifically, it asks the patient, “Over the past month, how often have you…”

- Had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finish urinating?

- Had to urinate again less than 2 hours after you finished urinating?

- Found you stopped and started again several times when you urinated?

- Found it difficult to postpone urination?

- Had a weak urinary stream?

- Had to push or strain to begin urination?

Each question above is scored as 0 (not at all), 1 (less than 1 time in 5), 2 (less than half the time), 3 (about half the time), 4 (more than half the time, or 5 (almost always).

- Over the past month, how many times did you most typically get up to urinate from the time you went to bed until the time you got up in the morning?

This question is scored from 0 (none) to 5 (5 times or more).

- If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that?

This question is scored as 0 (delighted), 1 (pleased), 2 (mostly satisfied), 3 (mixed: equally satisfied and dissatisfied), 4 (mostly dissatisfied), 5 (unhappy), or 6 (terrible).

A total score of 1 to 7 is categorized as mild, 8 to 19 moderate, and 20 to 35 severe.

The questionnaire can also be used to evaluate for disease progression and response to treatment over time. A change of 3 points is clinically significant, as patients are unable to discern a difference below this threshold.9

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is recommended to assess for urinary tract infection, hematuria, proteinuria, or glucosuria.

Fluid diary

A fluid diary is useful for patients complaining of frequency or nocturia and can help quantify the volume of fluid intake, frequency of urination, and volumes voided. The patient should complete the diary over a 24-hour period, recording the time and volume of fluid intake and each void. This aids in diagnosing polyuria (> 3 L of urine output per 24 hours), nocturnal polyuria, and behavioral causes of symptoms, including excessive total fluid intake or high evening fluid intake contributing to nocturia.

Serum creatinine not recommended

Measuring serum creatinine is not recommended in the initial BPH workup, as men with lower urinary tract symptoms are not at higher risk of renal failure than those without these symptoms.10

Prostate-specific antigen

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a glycoprotein primarily produced by prostatic luminal epithelial cells. It is most commonly discussed in the setting of prostate cancer screening, but its utility extends to guiding the management of BPH.

PSA levels correlate with prostate volume and subsequent growth.11 In addition, the risks of developing acute urinary retention or needing surgical intervention rise with increasing PSA.12 Among men in the Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study, the risk of acute urinary retention or BPH-related surgery after 4 years in the watchful-waiting arm was 7.8% in men with a PSA of 1.3 ng/dL or less, compared with 19.9% in men with a PSA greater than 3.2 ng/dL.11 Therefore, men with BPH and an elevated PSA are at higher risk with watchful waiting and may be better served with medical therapy.

In addition, American Urological Association guidelines recommend measuring serum PSA levels in men with a life expectancy greater than 10 years in whom the diagnosis of prostate cancer would alter management.10

Urologic referral

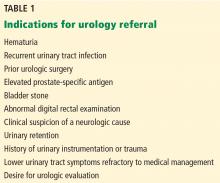

If the initial evaluation reveals hematuria, recurrent urinary tract infection, a palpable bladder, abnormal findings on digital rectal examination suggesting prostate cancer, or a history of or risk factors for urethral stricture or neurologic disease, the patient should be referred to a urologist for further evaluation (Table 1).10 Other patients who should undergo urologic evaluation are those with persistent bothersome symptoms after basic management and those who desire referral.

Adjunctive tests

Patients referred for urologic evaluation may require additional tests for diagnosis and to guide management.

Postvoid residual volume is easily measured with either abdominal ultrasonography or catheterization and is often included in the urologic evaluation of BPH. Patients vary considerably in their residual volume, which correlates poorly with BPH, symptom severity, or surgical success. However, those with a residual volume of more than 100 mL have a slightly higher rate of failure with watchful waiting.13 Postvoid residual volume is not routinely monitored in patients with a low residual volume unless there is a significant change in urinary symptoms. Conversely, patients with a volume greater than 200 mL should be monitored closely for worsening urinary retention, especially if considering anticholinergic therapy.

There is no absolute threshold postvoid residual volume above which therapy is mandatory. Rather, the decision to intervene is based on symptom severity and whether sequelae of urinary retention (eg, incontinence, urinary tract infection, hematuria, hydronephrosis, renal dysfunction) are present.

Uroflowmetry is a noninvasive test measuring the urinary flow rate during voiding and is recommended during specialist evaluation of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and suspected BPH.10 Though a diminished urinary flow rate may be detected in men with bladder outlet obstruction from BPH, it cannot differentiate obstruction from detrusor underactivity, both of which may result in reduced urinary flow. Urodynamic studies can help differentiate between these two mechanisms of lower urinary tract symptoms. Uroflowmetry may be useful in selecting surgical candidates, as patients with a maximum urinary flow rate of 15 mL/second or greater have been shown to have lower rates of surgical success.14

Urodynamic studies. If the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction remains in doubt, urodynamic studies can differentiate obstruction from detrusor underactivity. Urodynamic studies allow simultaneous measurement of urinary flow and detrusor pressure, differentiating between obstruction (manifesting as diminished urinary flow with normal or elevated detrusor pressure) and detrusor underactivity (diminished urinary flow with diminished detrusor pressure). Nomograms15 and the easily calculated bladder outlet obstruction index16 are simple tools used to differentiate these two causes of diminished urinary flow.

Cystourethroscopy is not recommended for routine evaluation of BPH. Indications for cystourethroscopy include hematuria and the presence of a risk factor for urethral stricture disease such as urethritis, prior urethral instrumentation, or perineal trauma. Cystourethroscopy can also aid in surgical planning when intervention is considered.

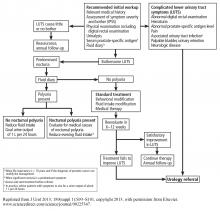

An algorithm for diagnostic workup and management of BPH and lower urinary tract symptoms is shown in Figure 3.17

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR BPH

While BPH is rarely life-threatening, it can significantly detract from a patient’s quality of life. The goal of treatment is not only to alleviate bothersome symptoms, but also to prevent disease progression and disease-related complications.

BPH tends to progress

Understanding the natural history of BPH is imperative to appropriately counsel patients on management options, which include watchful waiting, behavioral modification, pharmacologic therapy, and surgery.

In a randomized trial,18 men with moderately symptomatic BPH underwent either surgery or, in the control group, watchful waiting. At 5 years, the failure rate was 21% with watchful waiting vs 10% with surgery (P < .0004). (Failure was defined as a composite of death, repeated or intractable urinary retention, residual urine volume > 350 mL, development of bladder calculus, new persistent incontinence requiring use of a pad or other incontinence device, symptom score in the severe range [> 24 at 1 visit or score of 21 or higher at two consecutive visits, with 27 being the maximum score], or a doubling of baseline serum creatinine.) In the watchful-waiting group, 36% of the men crossed over to surgery. Men with more bothersome symptoms at enrollment were at higher risk of progressing to surgery.

In a longitudinal study of men with BPH and mild symptoms (IPSS < 8), the risk of progression to moderate or severe symptoms (IPPS ≥ 8) was 31% at 4 years.19

The Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status Among Men20 found that the peak urinary flow rate decreased by a mean of 2.1% per year, declining faster in older men who had a lower peak flow at baseline. In this cohort, the IPSS increased by a mean of 0.18 points per year, with a greater increase in older men.21

Though men managed with watchful waiting are at no higher risk of death or renal failure than men managed surgically,17 population-based studies have demonstrated an overall risk of acute urinary retention of 6.8/1,000 person-years with watchful waiting. Older men with a larger prostate, higher symptom score, and lower peak urinary flow rate are at higher risk of acute urinary retention and progression to needing BPH treatment.22,23

There is evidence that patients progressing to needing surgery after an initial period of watchful waiting have worse surgical outcomes than men managed surgically at the onset.18 This observation must be considered in counseling and selecting patients for watchful waiting. Ideal candidates include patients who have mild or moderate symptoms that cause little bother.10 Patients electing watchful waiting warrant annual follow-up including history, physical examination, and symptom assessment with the IPSS.

Behavioral modification

Behavioral modification should be incorporated into whichever management strategy a patient elects. Such modifications include:

- Reducing total or evening fluid intake for patients with urinary frequency or nocturia.

- Minimizing consumption of bladder irritants such as alcohol and caffeine, which exacerbate storage symptoms.

- Smoking cessation counseling.

- For patients with lower extremity edema who complain of nocturia, using compression stockings or elevating their legs in the afternoon to mobilize lower extremity edema and promote diuresis before going to sleep. If these measures fail, initiating or increasing the dose of a diuretic should be considered. Patients on diuretic therapy with nocturnal lower urinary tract symptoms should be instructed to take diuretics in the morning and early afternoon to avoid diuresis just before bed.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

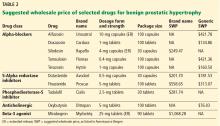

Drugs for BPH include alpha-adrenergic blockers, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, anticholinergics, beta-3 agonists, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Costs of selected agents in these classes are listed in Table 2.

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers

Alpha-adrenergic receptors are found throughout the body and modulate smooth muscle tone.24 The alpha-1a receptor is the predominant subtype found in the bladder neck and prostate25 (Figure 2) and is a target of therapy. By antagonizing the alpha-1a receptor, alpha-blockers relax the smooth muscle in the prostate and bladder neck, reduce bladder outlet resistance, and improve urinary flow.26

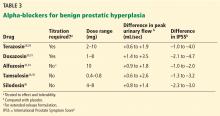

In clinical trials in BPH, alpha-blockers improved the symptom score by 30% to 45% and increased the peak urinary flow rate by 15% to 30% from baseline values.27 These agents have a rapid onset (within a few days) and result in significant symptom improvement. They are all about the same in efficacy (Table 3),28–36 with no strong evidence that any one of them is superior to another; thus, decisions about which agent to use must consider differences in receptor subtype specificity, adverse-effect profile, and tolerability.

In the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) trial,37 men randomized to the alpha-blocker doxazosin had a 39% lower risk of BPH progression than with placebo, largely due to symptom score reduction. However, doxazosin failed to reduce the risk of progressing to acute urinary retention or surgical intervention. Though rapidly effective in reducing symptoms, alpha-blocker monotherapy may not be the best option in men at higher risk of BPH progression, as discussed below.

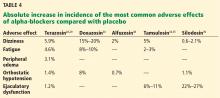

Before starting this therapy, patients must be counseled about common side effects such as dizziness, fatigue, peripheral edema, orthostatic hypotension, and ejaculatory dysfunction. The incidence of adverse effects varies among agents (Table 4).28–30,34,35,38,39

To maximize efficacy of alpha-blocker therapy, it is imperative to understand dosing variations among agents.

Alpha-blockers are classified as uroselective or non-uroselective based on alpha-1a receptor subtype specificity. The non-uroselective alpha-blockers doxazosin and terazosin need to be titrated because the higher the dose the greater the efficacy, but also the greater the blood pressure-lowering effect and other side effects.25 Though non-uroselective, alfuzosin does not affect blood pressure and does not require dose titration. Similarly, the uroselective alpha-blockers tamsulosin and silodosin can be initiated at a therapeutic dose.

Terazosin, a non-uroselective agent, can lower blood pressure and often causes dizziness. It should be started at 2 mg and titrated to side effects, efficacy, or maximum therapeutic dose (10 mg daily).28

Doxazosin has a high, dose-related incidence of dizziness (up to 20%) and must be titrated, starting at 1 mg to a maximum 8 mg.30

Alfuzosin, tamsulosin, and silodosin do not require titration and can be initiated at the therapeutic doses listed in Table 3. Of note, obese patients often require 0.8 mg tamsulosin for maximum efficacy due to a higher volume of distribution.

Before initiating an alpha-blocker, a physician must determine whether a patient plans to undergo cataract surgery, as the use of alpha-blockers is associated with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome. This condition is marked by poor intraoperative pupil dilation, increasing the risk of surgical complications.40 It is unclear whether discontinuing alpha-blockers before cataract surgery reduces the risk of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome. As such, alpha-blocker therapy should be delayed in patients planning to undergo cataract surgery.

5-Alpha reductase inhibitors

Prostate growth is androgen-dependent and mediated predominantly by dihydrotestosterone, which is generated from testosterone by the action of 5-alpha reductase. There are two 5-alpha reductase isoenzymes: type 1, expressed in the liver and skin, and type 2, expressed primarily in the prostate.

There are also two 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: dutasteride and finasteride. Dutasteride inhibits both isoenzymes, while finasteride is selective for type 2. By inhibiting both isoenzymes, dutasteride reduces the serum dihydrotestosterone concentration more than finasteride does (by 95% vs 70%), and also reduces the intraprostatic dihydrotestosterone concentration more (by 94% vs 80%).41–43 Both agents induce apoptosis of prostatic stroma, with a resultant 20% to 25% mean reduction in prostate volume.41,42

Finasteride and dutasteride are believed to mitigate the static obstructive component of BPH, with similar improvements in urinary flow rate (1.6–2.2 mL/sec) and symptom score (–2.7 to – 4.5 points) in men with an enlarged prostate.41,42 Indeed, data from the MTOPS trial showed that men with a prostate volume of 30 grams or greater or a PSA level of 1.5 ng/mL or greater are most likely to benefit from 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.37 Maximum symptomatic improvement is seen after 3 to 6 months of 5-alpha reductase inhibitor therapy.

In addition to improving urinary flow and lower urinary tract symptoms, finasteride has been shown to reduce the risk of disease progression in men with prostates greater than 30 grams.44 Compared with placebo, these drugs significantly reduce the risk of developing acute urinary retention or requiring BPH-related surgery, a benefit not seen with alpha-blockers.37 To estimate prostate volume, most practitioners rely on digital rectal examination. Though less precise than transrectal ultrasonography, digital rectal examination can identify men with significant prostatic enlargement likely to benefit from this therapy.

Before starting 5-alpha reductase inhibitor therapy, patients should be counseled about common adverse effects such as erectile dysfunction (occurring in 5%–8%), decreased libido (5%), ejaculatory dysfunction (1%–5%), and gynecomastia (1%).

Combination therapy

The MTOPS trial37 randomized patients to receive doxazosin, finasteride, both, or placebo. The combination of doxazosin (an alpha-blocker) and finasteride (a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor) reduced the risk of disease progression to a greater extent than doxazosin or finasteride alone. It also reduced the IPSS more and increased the peak urinary flow rate more. Similar results have been seen with the combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin.45

Given its superior efficacy and benefits in preventing disease progression, combination therapy should be considered for men with an enlarged prostate and moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms.

Anticholinergic agents

Anticholinergic agents block muscarinic receptors within the detrusor muscle, resulting in relaxation. They are used in the treatment of overactive bladder for symptoms of urinary urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence.

Anticholinergics were historically contraindicated in men with BPH because of concern about urinary retention. However, in men with a postvoid residual volume less than 200 mL, anticholinergics do not increase the risk of urinary retention.46 Further, greater symptom improvement has been demonstrated with the addition of anticholinergics to alpha-blocker therapy for men with BPH, irritative lower urinary tract symptoms, and a low postvoid residual volume.47

Beta-3 agonists

Anticholinergic side effects often limit the use of anticholinergic agents. An alternative in such instances is the beta-3 agonist mirabegron. By activating beta-3 adrenergic receptors in the bladder wall, mirabegron promotes detrusor relaxation and inhibits detrusor overactivity.48 Mirabegron does not have anticholinergic side effects and is generally well tolerated, though poorly controlled hypertension is a contraindication to its use.

Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors are a mainstay in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. These agents act within penile corporal smooth muscle cells and antagonize PDE5, resulting in cyclic guanosine monophosphate accumulation and smooth muscle relaxation. PDE5 is also found within the prostate and its inhibition is believed to reduce prostatic smooth muscle tone. Randomized studies have demonstrated significant improvement in lower urinary tract symptoms with PDE5 inhibitors, with an average 2-point IPSS improvement on a PDE5 inhibitor compared with placebo.49

Tadalafil is the only drug of this class approved by the FDA for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms, though other agents have demonstrated similar efficacy.

Dual therapy with a PDE5 inhibitor and an alpha-blocker has greater efficacy than either monotherapy alone; however, caution must be exercised as these agents are titrated to avoid symptomatic hypotension. Lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual dysfunction often coexist; PDE5 inhibitors are appropriate in the management of such cases.

SURGERY FOR BPH

Even with effective medical therapy, the disease will progress in some men. In the MTOPS trial,37 the 4-year incidence of disease progression was 10% for men on alpha-blocker or 5-alpha reductase inhibitor monotherapy and 5% for men on combination therapy; from 1% to 3% of those in the various treatment groups needed surgery. With this in mind, patients whose symptoms do not improve with medical therapy, whose symptoms progress, or who simply are interested in surgery should be referred for urologic evaluation.

A number of effective surgical therapies are available for men with BPH (Table 5), providing excellent 1-year outcomes including a mean 70% reduction in IPSS and a mean 12 mL/sec improvement in peak urinary flow.50 Given the efficacy of surgical therapy, men who do not improve with medical therapy who demonstrate any of the findings outlined in Table 1 warrant urologic evaluation.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Mary Ellen Amos, PharmD, and Kara Sink, BS, RPh, for their assistance in obtaining the suggested wholesale pricing information included in Table 2.

- Wei JT, Miner MM, Steers WD, et al; BPH Registry Steering Committee. Benign prostatic hyperplasia evaluation and management by urologists and primary care physicians: practice patterns from the observational BPH registry. J Urol 2011; 186:971–976.

- McNeal J. Pathology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. insight into etiology. Urol Clin North Am 1990; 17:477–486.

- Roehrborn CG, Schwinn DA. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors and their inhibitors in lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2004; 171:1029–1035.

- Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol 1984; 132:474–479.

- Platz EA, Smit E, Curhan GC, Nyberg LM, Giovannucci E. Prevalence of and racial/ethnic variation in lower urinary tract symptoms and noncancer prostate surgery in US men. Urology 2002; 59:877–883.

- Wei JT, Calhoun E, Jacobsen SJ. Urologic diseases in America project: benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2008; 179(suppl):S75–S80.

- Scheen AJ, Paquot N. Metabolic effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors beyond increased glucosuria: a review of the clinical evidence. Diabetes Metab 2014; 40(suppl 1):S4–S11.

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol 1992; 148:1549–1564.

- Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association symptom index and the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index is perceptible to patients? J Urol 1995; 154:1770–1774.

- McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, et al. Update on AUA guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2011; 185:1793–1803.

- Roehrborn CG, McConnell J, Bonilla J, et al. Serum prostate specific antigen is a strong predictor of future prostate growth in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. PROSCAR long-term efficacy and safety study. J Urol 2000; 163:13–20.

- Roehrborn CG, McConnell JD, Lieber M, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen concentration is a powerful predictor of acute urinary retention and need for surgery in men with clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. PLESS Study Group. Urology 1999; 53:473–480.

- Wasson JH, Reda DJ, Bruskewitz RC, Elinson J, Keller AM, Henderson WG. A comparison of transurethral surgery with watchful waiting for moderate symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:75–79.

- Jensen KM, Bruskewitz RC, Iversen P, Madsen PO. Spontaneous uroflowmetry in prostatism. Urology 1984; 24:403–409.

- Abrams PH, Griffiths DJ. The assessment of prostatic obstruction from urodynamic measurements and from residual urine. Br J Urol 1979; 51:129–134.

- Lim CS, Abrams P. The Abrams-Griffiths nomogram. World J Urol 1995; 13:34–39.

- Abrams P, Chapple C, Khoury S, Roehrborn C, de la Rosette J; International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Diseases. Evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older men. J Urol 2013; 189(suppl 1):S93–S101.

- Flanigan RC, Reda DJ, Wasson JH, Anderson RJ, Abdellatif M, Bruskewitz RC. 5-year outcome of surgical resection and watchful waiting for men with moderately symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. J Urol 1998; 160:12–17.

- Djavan B, Fong YK, Harik M, et al. Longitudinal study of men with mild symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction treated with watchful waiting for four years. Urology 2004; 64:1144–1148.

- Roberts RO, Jacobsen SJ, Jacobson DJ, Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Lieber MM. Longitudinal changes in peak urinary flow rates in a community based cohort. J Urol 2000; 163:107–113.

- Jacobsen SJ, Girman CJ, Guess HA, Rhodes T, Oesterling JE, Lieber MM. Natural history of prostatism: longitudinal changes in voiding symptoms in community dwelling men. J Urol 1996; 155:595–600.

- Jacobsen SJ, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among community dwelling men: the Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status. J Urol 1999; 162:1301–1306.

- Jacobsen SJ, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, et al. Natural history of prostatism: risk factors for acute urinary retention. J Urol 1997; 158:481–487.

- Kobayashi S, Tang R, Shapiro E, Lepor H. Characterization and localization of prostatic alpha 1 adrenoceptors using radioligand receptor binding on slide-mounted tissue section. J Urol 1993; 150:2002–2006.

- Kirby RS, Pool JL. Alpha adrenoceptor blockade in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: past, present and future. Br J Urol 1997; 80:521–532.

- Kirby RS, Pool JL. Alpha adrenoceptor blockade in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: past, present and future. Br J Urol 1997; 80:521–532.

- Milani S, Djavan B. Lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: latest update on alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists. BJU Int 2005; 95(suppl 4):29–36.

- Lepor H, Auerbach S, Puras-Baez A, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of terazosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 1992; 148:1467–1474.

- Roehrborn CG, Oesterling JE, Auerbach S, et al. The Hytrin Community Assessment Trial study: a one-year study of terazosin versus placebo in the treatment of men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. HYCAT Investigator Group. Urology 1996; 47:159–168.

- Gillenwater JY, Conn RL, Chrysant SG, et al. Doxazosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response multicenter study. J Urol 1995; 154:110–115.

- Chapple CR, Carter P, Christmas TJ, et al. A three month double-blind study of doxazosin as treatment for benign prostatic bladder outlet obstruction. Br J Urol 1994; 74:50–56.

- Buzelin JM, Roth S, Geffriaud-Ricouard C, Delauche-Cavallier MC. Efficacy and safety of sustained-release alfuzosin 5 mg in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. ALGEBI Study Group. Eur Urol 1997; 31:190–198.

- van Kerrebroeck P, Jardin A, Laval KU, van Cangh P. Efficacy and safety of a new prolonged release formulation of alfuzosin 10 mg once daily versus alfuzosin 2.5 mg thrice daily and placebo in patients with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. ALFORTI Study Group. Eur Urol 2000; 37:306–313.

- Narayan P, Tewari A. A second phase III multicenter placebo controlled study of 2 dosages of modified release tamsulosin in patients with symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. United States 93-01 Study Group. J Urol 1998; 160:1701–1706.

- Lepor H. Phase III multicenter placebo-controlled study of tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Tamsulosin Investigator Group. Urology 1998; 51:892–900.

- Ding H, Du W, Hou ZZ, Wang HZ, Wang ZP. Silodosin is effective for treatment of LUTS in men with BPH: a systematic review. Asian J Androl 2013; 15:121–128.

- McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al; Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) Research Group. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:2387–2398.

- Jardin A, Bensadoun H, Delauche-Cavallier MC, Attali P. Alfuzosin for treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy. The BPH-ALF Group. Lancet 1991; 337:1457–1461.

- Marks LS, Gittelman MC, Hill LA, Volinn W, Hoel G. Rapid efficacy of the highly selective alpha1A-adrenoceptor antagonist silodosin in men with signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia: pooled results of 2 phase 3 studies. J Urol 2009; 181:2634–2640.

- Chang DF, Campbell JR. Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome associated with tamsulosin. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005; 31:664–673.

- Gormley GJ, Stoner E, Bruskewitz RC, et al. The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Finasteride Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1185–1191.

- Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Nickel JC, Hoefner K, Andriole G; ARIA3001 ARIA3002 and ARIA3003 Study Investigators. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 2002; 60:434–441.

- Clark RV, Hermann DJ, Cunningham GR, Wilson TH, Morrill BB, Hobbs S. Marked suppression of dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia by dutasteride, a dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89:2179–2184.

- Kaplan SA, Lee JY, Meehan AG, Kusek JW; MTOPS Research Group. Long-term treatment with finasteride improves clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia in men with an enlarged versus a smaller prostate: data from the MTOPS trial. J Urol 2011; 185:1369–1373.

- Roehrborn CG, Siami P, Barkin J, et al; CombAT Study Group. The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study. Eur Urol 2010; 57:123–131.

- Abrams P, Kaplan S, De Koning Gans HJ, Millard R. Safety and tolerability of tolterodine for the treatment of overactive bladder in men with bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol 2006; 175:999–1004.

- Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, Carlsson M, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006; 296:2319–2328.

- Suarez O, Osborn D, Kaufman M, Reynolds WS, Dmochowski R. Mirabegron for male lower urinary tract symptoms. Curr Urol Rep 2013; 14:580–584.

- Oelke M, Giuliano F, Mirone V, Xu L, Cox D, Viktrup L. Monotherapy with tadalafil or tamsulosin similarly improved lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in an international, randomised, parallel, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur Urol 2012; 61:917–925.

- Welliver C, McVary KT. Minimally invasive and endoscopic management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:2504–2534.

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to screen for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and lower urinary tract symptoms, to perform the initial diagnostic workup, and to start medical therapy in uncomplicated cases. Effective medical therapy is available but underutilized in the primary care setting.1

This overview covers how to identify and evaluate patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, initiate therapy, and identify factors warranting timely urology referral.

TWO MECHANISMS: STATIC, DYNAMIC

BPH is a histologic diagnosis of proliferation of smooth muscle, epithelium, and stromal cells within the transition zone of the prostate,2 which surrounds the proximal urethra.

Symptoms arise through two mechanisms: static, in which the hyperplastic prostatic tissue compresses the urethra (Figure 1); and dynamic, with increased adrenergic nervous system and prostatic smooth muscle tone (Figure 2).3 Both mechanisms increase resistance to urinary flow at the level of the bladder outlet.

As an adaptive change to overcome outlet resistance and maintain urinary flow, the detrusor muscles undergo hypertrophy. However, over time the bladder may develop diminished compliance and increased detrusor activity, causing symptoms such as urinary frequency and urgency. Chronic bladder outlet obstruction can lead to bladder decompensation and detrusor underactivity, manifesting as incomplete emptying, urinary hesitancy, intermittency (starting and stopping while voiding), a weakened urinary stream, and urinary retention.

MOST MEN EVENTUALLY DEVELOP BPH

Autopsy studies have shown that BPH increases in prevalence with age beginning around age 30 and reaching a peak prevalence of 88% in men in their 80s.4 This trend parallels those of the incidence and severity of lower urinary tract symptoms.5

In the year 2000 alone, BPH was responsible for 4.5 million physician visits at an estimated direct cost of $1.1 billion, not including the cost of pharmacotherapy.6

OFFICE WORKUP

BPH can cause lower urinary tract symptoms that fall into two categories: storage and emptying. Storage symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia, whereas emptying symptoms include weak stream, hesitancy, intermittency, incomplete emptying, straining, and postvoid dribbling.

History and differential diagnosis

Assessment begins with characterizing the patient’s symptoms and determining those that are most bothersome. Because BPH is just one of many possible causes of lower urinary tract symptoms, a detailed medical history is necessary to evaluate for other conditions that may cause lower urinary tract dysfunction or complicate its treatment.

Obstructive urinary symptoms can arise from BPH or from other conditions, including urethral stricture disease and neurogenic voiding dysfunction.

Irritative voiding symptoms such as urinary urgency and frequency can result from detrusor overactivity secondary to BPH, but can also be caused by neurologic disease, malignancy, initiation of diuretic therapy, high fluid intake, or consumption of bladder irritants such as caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods.

Urinary frequency is sometimes a presenting symptom of undiagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus resulting from glucosuria and polyuria. Iatrogenic causes of polyuria include the new hypoglycemic agents canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, which block renal glucose reabsorption, improving glycemic control by inducing urinary

glucose loss.7

Nocturia has many possible nonurologic causes including heart failure (in which excess extravascular fluid shifts to the intravascular space when the patient lies down, resulting in polyuria), obstructive sleep apnea, and behavioral factors such as high evening fluid intake. In these cases, patients usually have nocturnal polyuria (greater than one-third of 24-hour urine output at night) rather than only nocturia (waking at night to void). A fluid diary is a simple tool that can differentiate these two conditions.

Hematuria can develop in patients with BPH with bleeding from congested prostatic or bladder neck vessels; however, hematuria may indicate an underlying malignancy or urolithiasis, for which a urologic workup is indicated.

The broad differential diagnosis for the different lower urinary tract symptoms highlights the importance of obtaining a thorough history.

Physical examination

A general examination should include the following:

Body mass index. Obese patients are at risk of obstructive sleep apnea, which can cause nocturnal polyuria.

Gait. Abnormal gait may suggest a neurologic condition such as Parkinson disease or stroke that can also affect lower urinary tract function.

Lower abdomen. A palpable bladder suggests urinary retention.

External genitalia. Penile causes of urinary obstruction include urethral meatal stenosis or a palpable urethral mass.

Digital rectal examination can reveal benign prostatic enlargement or nodules or firmness, which suggest malignancy and warrant urologic referral.

Neurologic examination, including evaluation of anal sphincter tone and lower extremity sensorimotor function.

Feet. Bilateral lower-extremity edema may be due to heart failure or venous insufficiency.

The International Prostate Symptom Score

All men with lower urinary tract symptoms should complete the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) survey, consisting of seven questions about urinary symptoms plus one about quality of life.8 Specifically, it asks the patient, “Over the past month, how often have you…”

- Had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finish urinating?

- Had to urinate again less than 2 hours after you finished urinating?

- Found you stopped and started again several times when you urinated?

- Found it difficult to postpone urination?

- Had a weak urinary stream?

- Had to push or strain to begin urination?

Each question above is scored as 0 (not at all), 1 (less than 1 time in 5), 2 (less than half the time), 3 (about half the time), 4 (more than half the time, or 5 (almost always).

- Over the past month, how many times did you most typically get up to urinate from the time you went to bed until the time you got up in the morning?

This question is scored from 0 (none) to 5 (5 times or more).

- If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that?

This question is scored as 0 (delighted), 1 (pleased), 2 (mostly satisfied), 3 (mixed: equally satisfied and dissatisfied), 4 (mostly dissatisfied), 5 (unhappy), or 6 (terrible).

A total score of 1 to 7 is categorized as mild, 8 to 19 moderate, and 20 to 35 severe.

The questionnaire can also be used to evaluate for disease progression and response to treatment over time. A change of 3 points is clinically significant, as patients are unable to discern a difference below this threshold.9

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is recommended to assess for urinary tract infection, hematuria, proteinuria, or glucosuria.

Fluid diary

A fluid diary is useful for patients complaining of frequency or nocturia and can help quantify the volume of fluid intake, frequency of urination, and volumes voided. The patient should complete the diary over a 24-hour period, recording the time and volume of fluid intake and each void. This aids in diagnosing polyuria (> 3 L of urine output per 24 hours), nocturnal polyuria, and behavioral causes of symptoms, including excessive total fluid intake or high evening fluid intake contributing to nocturia.

Serum creatinine not recommended

Measuring serum creatinine is not recommended in the initial BPH workup, as men with lower urinary tract symptoms are not at higher risk of renal failure than those without these symptoms.10

Prostate-specific antigen

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a glycoprotein primarily produced by prostatic luminal epithelial cells. It is most commonly discussed in the setting of prostate cancer screening, but its utility extends to guiding the management of BPH.

PSA levels correlate with prostate volume and subsequent growth.11 In addition, the risks of developing acute urinary retention or needing surgical intervention rise with increasing PSA.12 Among men in the Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study, the risk of acute urinary retention or BPH-related surgery after 4 years in the watchful-waiting arm was 7.8% in men with a PSA of 1.3 ng/dL or less, compared with 19.9% in men with a PSA greater than 3.2 ng/dL.11 Therefore, men with BPH and an elevated PSA are at higher risk with watchful waiting and may be better served with medical therapy.

In addition, American Urological Association guidelines recommend measuring serum PSA levels in men with a life expectancy greater than 10 years in whom the diagnosis of prostate cancer would alter management.10

Urologic referral

If the initial evaluation reveals hematuria, recurrent urinary tract infection, a palpable bladder, abnormal findings on digital rectal examination suggesting prostate cancer, or a history of or risk factors for urethral stricture or neurologic disease, the patient should be referred to a urologist for further evaluation (Table 1).10 Other patients who should undergo urologic evaluation are those with persistent bothersome symptoms after basic management and those who desire referral.

Adjunctive tests

Patients referred for urologic evaluation may require additional tests for diagnosis and to guide management.

Postvoid residual volume is easily measured with either abdominal ultrasonography or catheterization and is often included in the urologic evaluation of BPH. Patients vary considerably in their residual volume, which correlates poorly with BPH, symptom severity, or surgical success. However, those with a residual volume of more than 100 mL have a slightly higher rate of failure with watchful waiting.13 Postvoid residual volume is not routinely monitored in patients with a low residual volume unless there is a significant change in urinary symptoms. Conversely, patients with a volume greater than 200 mL should be monitored closely for worsening urinary retention, especially if considering anticholinergic therapy.

There is no absolute threshold postvoid residual volume above which therapy is mandatory. Rather, the decision to intervene is based on symptom severity and whether sequelae of urinary retention (eg, incontinence, urinary tract infection, hematuria, hydronephrosis, renal dysfunction) are present.

Uroflowmetry is a noninvasive test measuring the urinary flow rate during voiding and is recommended during specialist evaluation of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and suspected BPH.10 Though a diminished urinary flow rate may be detected in men with bladder outlet obstruction from BPH, it cannot differentiate obstruction from detrusor underactivity, both of which may result in reduced urinary flow. Urodynamic studies can help differentiate between these two mechanisms of lower urinary tract symptoms. Uroflowmetry may be useful in selecting surgical candidates, as patients with a maximum urinary flow rate of 15 mL/second or greater have been shown to have lower rates of surgical success.14

Urodynamic studies. If the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction remains in doubt, urodynamic studies can differentiate obstruction from detrusor underactivity. Urodynamic studies allow simultaneous measurement of urinary flow and detrusor pressure, differentiating between obstruction (manifesting as diminished urinary flow with normal or elevated detrusor pressure) and detrusor underactivity (diminished urinary flow with diminished detrusor pressure). Nomograms15 and the easily calculated bladder outlet obstruction index16 are simple tools used to differentiate these two causes of diminished urinary flow.

Cystourethroscopy is not recommended for routine evaluation of BPH. Indications for cystourethroscopy include hematuria and the presence of a risk factor for urethral stricture disease such as urethritis, prior urethral instrumentation, or perineal trauma. Cystourethroscopy can also aid in surgical planning when intervention is considered.

An algorithm for diagnostic workup and management of BPH and lower urinary tract symptoms is shown in Figure 3.17

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR BPH

While BPH is rarely life-threatening, it can significantly detract from a patient’s quality of life. The goal of treatment is not only to alleviate bothersome symptoms, but also to prevent disease progression and disease-related complications.

BPH tends to progress

Understanding the natural history of BPH is imperative to appropriately counsel patients on management options, which include watchful waiting, behavioral modification, pharmacologic therapy, and surgery.

In a randomized trial,18 men with moderately symptomatic BPH underwent either surgery or, in the control group, watchful waiting. At 5 years, the failure rate was 21% with watchful waiting vs 10% with surgery (P < .0004). (Failure was defined as a composite of death, repeated or intractable urinary retention, residual urine volume > 350 mL, development of bladder calculus, new persistent incontinence requiring use of a pad or other incontinence device, symptom score in the severe range [> 24 at 1 visit or score of 21 or higher at two consecutive visits, with 27 being the maximum score], or a doubling of baseline serum creatinine.) In the watchful-waiting group, 36% of the men crossed over to surgery. Men with more bothersome symptoms at enrollment were at higher risk of progressing to surgery.

In a longitudinal study of men with BPH and mild symptoms (IPSS < 8), the risk of progression to moderate or severe symptoms (IPPS ≥ 8) was 31% at 4 years.19

The Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status Among Men20 found that the peak urinary flow rate decreased by a mean of 2.1% per year, declining faster in older men who had a lower peak flow at baseline. In this cohort, the IPSS increased by a mean of 0.18 points per year, with a greater increase in older men.21

Though men managed with watchful waiting are at no higher risk of death or renal failure than men managed surgically,17 population-based studies have demonstrated an overall risk of acute urinary retention of 6.8/1,000 person-years with watchful waiting. Older men with a larger prostate, higher symptom score, and lower peak urinary flow rate are at higher risk of acute urinary retention and progression to needing BPH treatment.22,23

There is evidence that patients progressing to needing surgery after an initial period of watchful waiting have worse surgical outcomes than men managed surgically at the onset.18 This observation must be considered in counseling and selecting patients for watchful waiting. Ideal candidates include patients who have mild or moderate symptoms that cause little bother.10 Patients electing watchful waiting warrant annual follow-up including history, physical examination, and symptom assessment with the IPSS.

Behavioral modification

Behavioral modification should be incorporated into whichever management strategy a patient elects. Such modifications include:

- Reducing total or evening fluid intake for patients with urinary frequency or nocturia.

- Minimizing consumption of bladder irritants such as alcohol and caffeine, which exacerbate storage symptoms.

- Smoking cessation counseling.

- For patients with lower extremity edema who complain of nocturia, using compression stockings or elevating their legs in the afternoon to mobilize lower extremity edema and promote diuresis before going to sleep. If these measures fail, initiating or increasing the dose of a diuretic should be considered. Patients on diuretic therapy with nocturnal lower urinary tract symptoms should be instructed to take diuretics in the morning and early afternoon to avoid diuresis just before bed.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Drugs for BPH include alpha-adrenergic blockers, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, anticholinergics, beta-3 agonists, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Costs of selected agents in these classes are listed in Table 2.

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers

Alpha-adrenergic receptors are found throughout the body and modulate smooth muscle tone.24 The alpha-1a receptor is the predominant subtype found in the bladder neck and prostate25 (Figure 2) and is a target of therapy. By antagonizing the alpha-1a receptor, alpha-blockers relax the smooth muscle in the prostate and bladder neck, reduce bladder outlet resistance, and improve urinary flow.26

In clinical trials in BPH, alpha-blockers improved the symptom score by 30% to 45% and increased the peak urinary flow rate by 15% to 30% from baseline values.27 These agents have a rapid onset (within a few days) and result in significant symptom improvement. They are all about the same in efficacy (Table 3),28–36 with no strong evidence that any one of them is superior to another; thus, decisions about which agent to use must consider differences in receptor subtype specificity, adverse-effect profile, and tolerability.

In the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) trial,37 men randomized to the alpha-blocker doxazosin had a 39% lower risk of BPH progression than with placebo, largely due to symptom score reduction. However, doxazosin failed to reduce the risk of progressing to acute urinary retention or surgical intervention. Though rapidly effective in reducing symptoms, alpha-blocker monotherapy may not be the best option in men at higher risk of BPH progression, as discussed below.

Before starting this therapy, patients must be counseled about common side effects such as dizziness, fatigue, peripheral edema, orthostatic hypotension, and ejaculatory dysfunction. The incidence of adverse effects varies among agents (Table 4).28–30,34,35,38,39

To maximize efficacy of alpha-blocker therapy, it is imperative to understand dosing variations among agents.

Alpha-blockers are classified as uroselective or non-uroselective based on alpha-1a receptor subtype specificity. The non-uroselective alpha-blockers doxazosin and terazosin need to be titrated because the higher the dose the greater the efficacy, but also the greater the blood pressure-lowering effect and other side effects.25 Though non-uroselective, alfuzosin does not affect blood pressure and does not require dose titration. Similarly, the uroselective alpha-blockers tamsulosin and silodosin can be initiated at a therapeutic dose.

Terazosin, a non-uroselective agent, can lower blood pressure and often causes dizziness. It should be started at 2 mg and titrated to side effects, efficacy, or maximum therapeutic dose (10 mg daily).28

Doxazosin has a high, dose-related incidence of dizziness (up to 20%) and must be titrated, starting at 1 mg to a maximum 8 mg.30

Alfuzosin, tamsulosin, and silodosin do not require titration and can be initiated at the therapeutic doses listed in Table 3. Of note, obese patients often require 0.8 mg tamsulosin for maximum efficacy due to a higher volume of distribution.

Before initiating an alpha-blocker, a physician must determine whether a patient plans to undergo cataract surgery, as the use of alpha-blockers is associated with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome. This condition is marked by poor intraoperative pupil dilation, increasing the risk of surgical complications.40 It is unclear whether discontinuing alpha-blockers before cataract surgery reduces the risk of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome. As such, alpha-blocker therapy should be delayed in patients planning to undergo cataract surgery.

5-Alpha reductase inhibitors

Prostate growth is androgen-dependent and mediated predominantly by dihydrotestosterone, which is generated from testosterone by the action of 5-alpha reductase. There are two 5-alpha reductase isoenzymes: type 1, expressed in the liver and skin, and type 2, expressed primarily in the prostate.

There are also two 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: dutasteride and finasteride. Dutasteride inhibits both isoenzymes, while finasteride is selective for type 2. By inhibiting both isoenzymes, dutasteride reduces the serum dihydrotestosterone concentration more than finasteride does (by 95% vs 70%), and also reduces the intraprostatic dihydrotestosterone concentration more (by 94% vs 80%).41–43 Both agents induce apoptosis of prostatic stroma, with a resultant 20% to 25% mean reduction in prostate volume.41,42

Finasteride and dutasteride are believed to mitigate the static obstructive component of BPH, with similar improvements in urinary flow rate (1.6–2.2 mL/sec) and symptom score (–2.7 to – 4.5 points) in men with an enlarged prostate.41,42 Indeed, data from the MTOPS trial showed that men with a prostate volume of 30 grams or greater or a PSA level of 1.5 ng/mL or greater are most likely to benefit from 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.37 Maximum symptomatic improvement is seen after 3 to 6 months of 5-alpha reductase inhibitor therapy.

In addition to improving urinary flow and lower urinary tract symptoms, finasteride has been shown to reduce the risk of disease progression in men with prostates greater than 30 grams.44 Compared with placebo, these drugs significantly reduce the risk of developing acute urinary retention or requiring BPH-related surgery, a benefit not seen with alpha-blockers.37 To estimate prostate volume, most practitioners rely on digital rectal examination. Though less precise than transrectal ultrasonography, digital rectal examination can identify men with significant prostatic enlargement likely to benefit from this therapy.

Before starting 5-alpha reductase inhibitor therapy, patients should be counseled about common adverse effects such as erectile dysfunction (occurring in 5%–8%), decreased libido (5%), ejaculatory dysfunction (1%–5%), and gynecomastia (1%).

Combination therapy

The MTOPS trial37 randomized patients to receive doxazosin, finasteride, both, or placebo. The combination of doxazosin (an alpha-blocker) and finasteride (a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor) reduced the risk of disease progression to a greater extent than doxazosin or finasteride alone. It also reduced the IPSS more and increased the peak urinary flow rate more. Similar results have been seen with the combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin.45

Given its superior efficacy and benefits in preventing disease progression, combination therapy should be considered for men with an enlarged prostate and moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms.

Anticholinergic agents

Anticholinergic agents block muscarinic receptors within the detrusor muscle, resulting in relaxation. They are used in the treatment of overactive bladder for symptoms of urinary urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence.

Anticholinergics were historically contraindicated in men with BPH because of concern about urinary retention. However, in men with a postvoid residual volume less than 200 mL, anticholinergics do not increase the risk of urinary retention.46 Further, greater symptom improvement has been demonstrated with the addition of anticholinergics to alpha-blocker therapy for men with BPH, irritative lower urinary tract symptoms, and a low postvoid residual volume.47

Beta-3 agonists

Anticholinergic side effects often limit the use of anticholinergic agents. An alternative in such instances is the beta-3 agonist mirabegron. By activating beta-3 adrenergic receptors in the bladder wall, mirabegron promotes detrusor relaxation and inhibits detrusor overactivity.48 Mirabegron does not have anticholinergic side effects and is generally well tolerated, though poorly controlled hypertension is a contraindication to its use.

Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors are a mainstay in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. These agents act within penile corporal smooth muscle cells and antagonize PDE5, resulting in cyclic guanosine monophosphate accumulation and smooth muscle relaxation. PDE5 is also found within the prostate and its inhibition is believed to reduce prostatic smooth muscle tone. Randomized studies have demonstrated significant improvement in lower urinary tract symptoms with PDE5 inhibitors, with an average 2-point IPSS improvement on a PDE5 inhibitor compared with placebo.49

Tadalafil is the only drug of this class approved by the FDA for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms, though other agents have demonstrated similar efficacy.

Dual therapy with a PDE5 inhibitor and an alpha-blocker has greater efficacy than either monotherapy alone; however, caution must be exercised as these agents are titrated to avoid symptomatic hypotension. Lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual dysfunction often coexist; PDE5 inhibitors are appropriate in the management of such cases.

SURGERY FOR BPH

Even with effective medical therapy, the disease will progress in some men. In the MTOPS trial,37 the 4-year incidence of disease progression was 10% for men on alpha-blocker or 5-alpha reductase inhibitor monotherapy and 5% for men on combination therapy; from 1% to 3% of those in the various treatment groups needed surgery. With this in mind, patients whose symptoms do not improve with medical therapy, whose symptoms progress, or who simply are interested in surgery should be referred for urologic evaluation.

A number of effective surgical therapies are available for men with BPH (Table 5), providing excellent 1-year outcomes including a mean 70% reduction in IPSS and a mean 12 mL/sec improvement in peak urinary flow.50 Given the efficacy of surgical therapy, men who do not improve with medical therapy who demonstrate any of the findings outlined in Table 1 warrant urologic evaluation.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Mary Ellen Amos, PharmD, and Kara Sink, BS, RPh, for their assistance in obtaining the suggested wholesale pricing information included in Table 2.

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to screen for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and lower urinary tract symptoms, to perform the initial diagnostic workup, and to start medical therapy in uncomplicated cases. Effective medical therapy is available but underutilized in the primary care setting.1

This overview covers how to identify and evaluate patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, initiate therapy, and identify factors warranting timely urology referral.

TWO MECHANISMS: STATIC, DYNAMIC

BPH is a histologic diagnosis of proliferation of smooth muscle, epithelium, and stromal cells within the transition zone of the prostate,2 which surrounds the proximal urethra.

Symptoms arise through two mechanisms: static, in which the hyperplastic prostatic tissue compresses the urethra (Figure 1); and dynamic, with increased adrenergic nervous system and prostatic smooth muscle tone (Figure 2).3 Both mechanisms increase resistance to urinary flow at the level of the bladder outlet.

As an adaptive change to overcome outlet resistance and maintain urinary flow, the detrusor muscles undergo hypertrophy. However, over time the bladder may develop diminished compliance and increased detrusor activity, causing symptoms such as urinary frequency and urgency. Chronic bladder outlet obstruction can lead to bladder decompensation and detrusor underactivity, manifesting as incomplete emptying, urinary hesitancy, intermittency (starting and stopping while voiding), a weakened urinary stream, and urinary retention.

MOST MEN EVENTUALLY DEVELOP BPH

Autopsy studies have shown that BPH increases in prevalence with age beginning around age 30 and reaching a peak prevalence of 88% in men in their 80s.4 This trend parallels those of the incidence and severity of lower urinary tract symptoms.5

In the year 2000 alone, BPH was responsible for 4.5 million physician visits at an estimated direct cost of $1.1 billion, not including the cost of pharmacotherapy.6

OFFICE WORKUP

BPH can cause lower urinary tract symptoms that fall into two categories: storage and emptying. Storage symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia, whereas emptying symptoms include weak stream, hesitancy, intermittency, incomplete emptying, straining, and postvoid dribbling.

History and differential diagnosis

Assessment begins with characterizing the patient’s symptoms and determining those that are most bothersome. Because BPH is just one of many possible causes of lower urinary tract symptoms, a detailed medical history is necessary to evaluate for other conditions that may cause lower urinary tract dysfunction or complicate its treatment.

Obstructive urinary symptoms can arise from BPH or from other conditions, including urethral stricture disease and neurogenic voiding dysfunction.

Irritative voiding symptoms such as urinary urgency and frequency can result from detrusor overactivity secondary to BPH, but can also be caused by neurologic disease, malignancy, initiation of diuretic therapy, high fluid intake, or consumption of bladder irritants such as caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods.

Urinary frequency is sometimes a presenting symptom of undiagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus resulting from glucosuria and polyuria. Iatrogenic causes of polyuria include the new hypoglycemic agents canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, which block renal glucose reabsorption, improving glycemic control by inducing urinary

glucose loss.7

Nocturia has many possible nonurologic causes including heart failure (in which excess extravascular fluid shifts to the intravascular space when the patient lies down, resulting in polyuria), obstructive sleep apnea, and behavioral factors such as high evening fluid intake. In these cases, patients usually have nocturnal polyuria (greater than one-third of 24-hour urine output at night) rather than only nocturia (waking at night to void). A fluid diary is a simple tool that can differentiate these two conditions.

Hematuria can develop in patients with BPH with bleeding from congested prostatic or bladder neck vessels; however, hematuria may indicate an underlying malignancy or urolithiasis, for which a urologic workup is indicated.

The broad differential diagnosis for the different lower urinary tract symptoms highlights the importance of obtaining a thorough history.

Physical examination

A general examination should include the following:

Body mass index. Obese patients are at risk of obstructive sleep apnea, which can cause nocturnal polyuria.

Gait. Abnormal gait may suggest a neurologic condition such as Parkinson disease or stroke that can also affect lower urinary tract function.

Lower abdomen. A palpable bladder suggests urinary retention.

External genitalia. Penile causes of urinary obstruction include urethral meatal stenosis or a palpable urethral mass.

Digital rectal examination can reveal benign prostatic enlargement or nodules or firmness, which suggest malignancy and warrant urologic referral.

Neurologic examination, including evaluation of anal sphincter tone and lower extremity sensorimotor function.

Feet. Bilateral lower-extremity edema may be due to heart failure or venous insufficiency.

The International Prostate Symptom Score

All men with lower urinary tract symptoms should complete the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) survey, consisting of seven questions about urinary symptoms plus one about quality of life.8 Specifically, it asks the patient, “Over the past month, how often have you…”

- Had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finish urinating?

- Had to urinate again less than 2 hours after you finished urinating?

- Found you stopped and started again several times when you urinated?

- Found it difficult to postpone urination?

- Had a weak urinary stream?

- Had to push or strain to begin urination?

Each question above is scored as 0 (not at all), 1 (less than 1 time in 5), 2 (less than half the time), 3 (about half the time), 4 (more than half the time, or 5 (almost always).

- Over the past month, how many times did you most typically get up to urinate from the time you went to bed until the time you got up in the morning?

This question is scored from 0 (none) to 5 (5 times or more).

- If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that?

This question is scored as 0 (delighted), 1 (pleased), 2 (mostly satisfied), 3 (mixed: equally satisfied and dissatisfied), 4 (mostly dissatisfied), 5 (unhappy), or 6 (terrible).

A total score of 1 to 7 is categorized as mild, 8 to 19 moderate, and 20 to 35 severe.

The questionnaire can also be used to evaluate for disease progression and response to treatment over time. A change of 3 points is clinically significant, as patients are unable to discern a difference below this threshold.9

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is recommended to assess for urinary tract infection, hematuria, proteinuria, or glucosuria.

Fluid diary

A fluid diary is useful for patients complaining of frequency or nocturia and can help quantify the volume of fluid intake, frequency of urination, and volumes voided. The patient should complete the diary over a 24-hour period, recording the time and volume of fluid intake and each void. This aids in diagnosing polyuria (> 3 L of urine output per 24 hours), nocturnal polyuria, and behavioral causes of symptoms, including excessive total fluid intake or high evening fluid intake contributing to nocturia.

Serum creatinine not recommended

Measuring serum creatinine is not recommended in the initial BPH workup, as men with lower urinary tract symptoms are not at higher risk of renal failure than those without these symptoms.10

Prostate-specific antigen

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a glycoprotein primarily produced by prostatic luminal epithelial cells. It is most commonly discussed in the setting of prostate cancer screening, but its utility extends to guiding the management of BPH.

PSA levels correlate with prostate volume and subsequent growth.11 In addition, the risks of developing acute urinary retention or needing surgical intervention rise with increasing PSA.12 Among men in the Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study, the risk of acute urinary retention or BPH-related surgery after 4 years in the watchful-waiting arm was 7.8% in men with a PSA of 1.3 ng/dL or less, compared with 19.9% in men with a PSA greater than 3.2 ng/dL.11 Therefore, men with BPH and an elevated PSA are at higher risk with watchful waiting and may be better served with medical therapy.

In addition, American Urological Association guidelines recommend measuring serum PSA levels in men with a life expectancy greater than 10 years in whom the diagnosis of prostate cancer would alter management.10

Urologic referral

If the initial evaluation reveals hematuria, recurrent urinary tract infection, a palpable bladder, abnormal findings on digital rectal examination suggesting prostate cancer, or a history of or risk factors for urethral stricture or neurologic disease, the patient should be referred to a urologist for further evaluation (Table 1).10 Other patients who should undergo urologic evaluation are those with persistent bothersome symptoms after basic management and those who desire referral.

Adjunctive tests

Patients referred for urologic evaluation may require additional tests for diagnosis and to guide management.

Postvoid residual volume is easily measured with either abdominal ultrasonography or catheterization and is often included in the urologic evaluation of BPH. Patients vary considerably in their residual volume, which correlates poorly with BPH, symptom severity, or surgical success. However, those with a residual volume of more than 100 mL have a slightly higher rate of failure with watchful waiting.13 Postvoid residual volume is not routinely monitored in patients with a low residual volume unless there is a significant change in urinary symptoms. Conversely, patients with a volume greater than 200 mL should be monitored closely for worsening urinary retention, especially if considering anticholinergic therapy.

There is no absolute threshold postvoid residual volume above which therapy is mandatory. Rather, the decision to intervene is based on symptom severity and whether sequelae of urinary retention (eg, incontinence, urinary tract infection, hematuria, hydronephrosis, renal dysfunction) are present.

Uroflowmetry is a noninvasive test measuring the urinary flow rate during voiding and is recommended during specialist evaluation of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and suspected BPH.10 Though a diminished urinary flow rate may be detected in men with bladder outlet obstruction from BPH, it cannot differentiate obstruction from detrusor underactivity, both of which may result in reduced urinary flow. Urodynamic studies can help differentiate between these two mechanisms of lower urinary tract symptoms. Uroflowmetry may be useful in selecting surgical candidates, as patients with a maximum urinary flow rate of 15 mL/second or greater have been shown to have lower rates of surgical success.14

Urodynamic studies. If the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction remains in doubt, urodynamic studies can differentiate obstruction from detrusor underactivity. Urodynamic studies allow simultaneous measurement of urinary flow and detrusor pressure, differentiating between obstruction (manifesting as diminished urinary flow with normal or elevated detrusor pressure) and detrusor underactivity (diminished urinary flow with diminished detrusor pressure). Nomograms15 and the easily calculated bladder outlet obstruction index16 are simple tools used to differentiate these two causes of diminished urinary flow.

Cystourethroscopy is not recommended for routine evaluation of BPH. Indications for cystourethroscopy include hematuria and the presence of a risk factor for urethral stricture disease such as urethritis, prior urethral instrumentation, or perineal trauma. Cystourethroscopy can also aid in surgical planning when intervention is considered.

An algorithm for diagnostic workup and management of BPH and lower urinary tract symptoms is shown in Figure 3.17

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR BPH

While BPH is rarely life-threatening, it can significantly detract from a patient’s quality of life. The goal of treatment is not only to alleviate bothersome symptoms, but also to prevent disease progression and disease-related complications.

BPH tends to progress

Understanding the natural history of BPH is imperative to appropriately counsel patients on management options, which include watchful waiting, behavioral modification, pharmacologic therapy, and surgery.

In a randomized trial,18 men with moderately symptomatic BPH underwent either surgery or, in the control group, watchful waiting. At 5 years, the failure rate was 21% with watchful waiting vs 10% with surgery (P < .0004). (Failure was defined as a composite of death, repeated or intractable urinary retention, residual urine volume > 350 mL, development of bladder calculus, new persistent incontinence requiring use of a pad or other incontinence device, symptom score in the severe range [> 24 at 1 visit or score of 21 or higher at two consecutive visits, with 27 being the maximum score], or a doubling of baseline serum creatinine.) In the watchful-waiting group, 36% of the men crossed over to surgery. Men with more bothersome symptoms at enrollment were at higher risk of progressing to surgery.

In a longitudinal study of men with BPH and mild symptoms (IPSS < 8), the risk of progression to moderate or severe symptoms (IPPS ≥ 8) was 31% at 4 years.19

The Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status Among Men20 found that the peak urinary flow rate decreased by a mean of 2.1% per year, declining faster in older men who had a lower peak flow at baseline. In this cohort, the IPSS increased by a mean of 0.18 points per year, with a greater increase in older men.21

Though men managed with watchful waiting are at no higher risk of death or renal failure than men managed surgically,17 population-based studies have demonstrated an overall risk of acute urinary retention of 6.8/1,000 person-years with watchful waiting. Older men with a larger prostate, higher symptom score, and lower peak urinary flow rate are at higher risk of acute urinary retention and progression to needing BPH treatment.22,23

There is evidence that patients progressing to needing surgery after an initial period of watchful waiting have worse surgical outcomes than men managed surgically at the onset.18 This observation must be considered in counseling and selecting patients for watchful waiting. Ideal candidates include patients who have mild or moderate symptoms that cause little bother.10 Patients electing watchful waiting warrant annual follow-up including history, physical examination, and symptom assessment with the IPSS.

Behavioral modification

Behavioral modification should be incorporated into whichever management strategy a patient elects. Such modifications include:

- Reducing total or evening fluid intake for patients with urinary frequency or nocturia.

- Minimizing consumption of bladder irritants such as alcohol and caffeine, which exacerbate storage symptoms.

- Smoking cessation counseling.

- For patients with lower extremity edema who complain of nocturia, using compression stockings or elevating their legs in the afternoon to mobilize lower extremity edema and promote diuresis before going to sleep. If these measures fail, initiating or increasing the dose of a diuretic should be considered. Patients on diuretic therapy with nocturnal lower urinary tract symptoms should be instructed to take diuretics in the morning and early afternoon to avoid diuresis just before bed.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT