User login

Psychiatrists in the trenches are not alone in being unsure how to treat breakthrough bipolar depression. No panelist or other expert attending a recent American College of Neuropsychopharmacology symposium could definitively recommend:

- when to add an antidepressant to mood-stabilizer therapy

- whether to discontinue antidepressants after bipolar depression is stabilized.

Until controlled trials address these issues, we must use limited evidence to treat patients with bipolar depression. To help you meet this challenge, this article offers provisional suggestions based on recent published and unpublished reports.

Evidence for continuing

No published, randomized studies have examined how long to continue antidepressants after bipolar depression has stabilized. Until recently, conventional wisdom has been to discontinue antidepressants as soon as possible because of worries about antidepressant-induced mania. Then two case-controlled studies—one retrospective and one prospective—challenged that assumption.

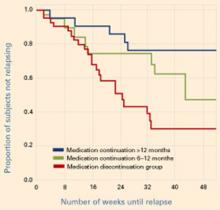

Figure Reduced relapse rates in patients whose antidepressants were continued

In a prospective case-controlled study, patients with bipolar disorder who continued antidepressant treatment for 6 to 12 months or >12 months after depressive episode remission had lower relapse rates than those who discontinued antidepressants within 6 months.

Source: Reprinted with permission from reference 2. Copyright 2003. American Psychiatric AssociationUsing similar methodologies, Altshuler et al1,2 examined bipolar patients who remained in remission for 6 weeks on mood stabilizers plus adjunctive antidepressants. Those who continued the antidepressants were less likely to relapse into depression (without an increase in manic episodes) than those whose antidepressants were discontinued (Figure).

Relapse rates in the first study1 were 35% at 1 year in those who continued antidepressants and 68% in those who did not. In the second study,2 36% and 70% of patients, respectively, had relapsed at 1 year. In the latter study, those who continued to take antidepressants for at least 6 months—instead of at least 12 months—had intermediate depressive relapse rates (53% for 6 months vs. 24% for 12 months).

When interpreting these data, keep several caveats in mind. For one, patients were not randomly assigned to continue or discontinue antidepressants but were designated by patient and clinician choice. When comparing the two patient groups, however, the authors found no inherent differences in illness characteristics that might have biased the results.

More importantly, few patients initially treated with antidepressant augmentation responded well and remained in remission. In the prospective study, 549 of 1,078 patients in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network received an antidepressant for breakthrough depressive symptoms.2 Only 189 remained on antidepressants for 2 months, and only 84 (15%) of the original population remained in remission for 2 months.

Summary. A small subgroup of patients appears to respond well to antidepressants and sustains this response for 6 to 8 weeks. For this subset, continuing antidepressant therapy would appear to be an appropriate strategy, based on:

- a significantly reduced risk for depressive relapse

- no increased risk of switching to mania, which is the usual reason to terminate antidepressants early.

Subsequent evidence

One needs to assess these observations in light of an interim analysis reported halfway through a small, open, randomized study. Ghaemi et al3 found no significant difference in outcomes—regardless of rapid-cycling status—among 14 bipolar patients who remained on antidepressants and 19 who discontinued across an average 60 and 50 weeks, respectively.

Table

Evidence on continuing antidepressants in breakthrough bipolar depression

| Study | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Altshuler et al 1 | Retrospective, case-control, 39 patients (1 year) | Relapse rates: 35% in patients who continued antidepressants after mood stabilization and and 68% in those who did not; study included no rapid-cyclers |

| Altshuler et al 2 | Prospective, case control 84 patients (1 year) | Relapse rates: 36% in patients who continued antidepressants after mood stabilization and 70% in those who did not; study included no rapid cyclers |

| Ghaemi et al 3 (unpublished) | Open, randomized 33 patients (approx. 1 yr) | Relapse rate: 50% within 20 weeks, whether or not patients continued antidepressants; one-third of patients were rapid cyclers |

A survival analysis initially suggested some benefit for continuing antidepressants, but this disappeared when the authors adjusted for potential confounding factors—which was not done in the Altshuler et al studies. Patients receiving short-term or long-term antidepressants had a similar number of depressive episodes per year (1.00 vs. 0.75 episodes/year, respectively). For some reason, nonrapid-cycling patients showed greater depressive morbidity than those with rapid cycling.

Rapid cyclers comprised 30% of patients who continued antidepressants and 37% of those who discontinued. This may explain the 50% relapse rate within 20 weeks in both groups. By comparison, the Altshuler et al studies included no rapid cyclers.1,2 More details on this unpublished data are expected.

Are antidepressants the answer?

The high relapse rate in patients taking mood stabilizers—with or without an antidepressant—and the Ghaemi et al data3 suggest that we need alternate antidepressant approaches to bipolar depression. Potential regimens—anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics, and other agents—merit further study. So far the evidence is mixed, and the most effective approaches are not well-delineated.

Anticonvulsants. Sachs et al4 reported that adding lamotrigine or lamotrigine plus an antidepressant to mood stabilizer therapy did not appear more effective in treating bipolar depression than simply maintaining the mood stabilizers.

Similarly, a small randomized, double-blind study in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) was stopped early because of low total response. Adjunctive lamotrigine (24%) and inositol (17%) appeared more effective than risperidone (5%) for refractory bipolar depression.

Antipsychotics. In an 8-week randomized trial by Tohen et al,5 833 patients with moderate to severe bipolar I depression were treated with olanzapine, olanzapine plus fluoxetine, or placebo. Core depression symptoms improved significantly more with olanzapine alone or with fluoxetine compared with placebo, as measured by mean changes in the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

In a 6-month open trial, 192 patients whose bipolar I depression remitted with any of the three treatments6 continued olanzapine and then, if needed after the first week, the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC). Nearly two-thirds of patients (62%) remained without a depressive recurrence, and 94% remained without a manic recurrence while taking the OFC. These unpublished data indicate that the OFC provided greater prophylactic antimanic than antidepressant effects.

Calabrese et al7 recently presented unpublished data comparing the effects of quetiapine monotherapy, 300 or 600 mg/d, with placebo in patients with bipolar depression. Beginning in the first week of treatment, both quetiapine dosages produced significantly greater antidepressant, antianxiety, and anti-insomnia effects than placebo (P < 0.001). Remission rates with both dosages were >50%.

Summary. These first controlled studies of atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression suggest that this drug class may have antidepressant as well as their demonstrated antimanic effects.

Recommendations—for now

Controlled clinical trials have not been conducted, and the evidence on using adjunctive antidepressants in bipolar depression is ambiguous.8-11 As a result, it is unclear when or how long to use antidepressants, and many of the inferences and suggestions in this paper remain highly provisional.

Initiating antidepressants. My personal treatment guidelines—and those of many other clinicians—are to use the unimodal antidepressants to augment mood stabilizers in bipolar patients experiencing breakthrough depression, as long as they have not had:

- ultra-rapid cycling (>4 episodes/week)

- antidepressant-induced cycle acceleration

- or multiple episodes of antidepressant-induced mania, despite co-treatment with mood stabilizers.

If any of these variables is present, I would instead add another mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic.

Continuing antidepressants. If the patient remains stable for 2 months after the antidepressant is added—with no depression or manic occurrence—I would continue the antidepressant indefinitely, based on the Altshuler et al data.12

Mood charting.I also recommend that clinicians help patients develop an individual method for mood charting, such as that used in the National Institute of Mental Health Life Chart Method (NIMH-LCM)12,13 or the STEP-BD program.14 Goals of the 5-year STEP-BD are to:

- determine the most effective treatments and relapse prevention strategies for bipolar disorder

- evaluate the psychotropic benefit of anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics, cholinesterase inhibitors, and neurotransmitter precursors

- determine the benefit of psychotropic combinations.

Mood charts can provide a retrospective and prospective overview of a patient’s illness course and response to medications. Compared with patient recall, mood charts help clinicians evaluate more precisely the risk of switching and the risks and benefits of starting, continuing, or discontinuing antidepressants. Mood charts may be your most effective tool for managing a patient’s bipolar depression and achieving and maintaining long-term remission.

Summary. In the absence of consensus or guidelines for treating bipolar depression, I suggest:

- a conservative approach—ie, no changes in medication—when the patient remains well on a given regimen

- an aggressive—if not radical—series of treatments and revisions when the illness course remains problematic.

Many medication classes and adjunctive strategies are available for treating bipolar illness.15-18 I recommend that you continue to systematically explore adjunctive treatments and combinations until the patient improves or—even better—attains remission. Good response can be achieved—even in treatment-refractory patients ill for long periods or with recurrent bipolar depression—although complex combination therapy is often required.

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health-Life Chart Method. Retrospective and prospective mood-tracking charts for patients with bipolar disorder. www.bipolarnews.org

- Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Depression (STEP-BD). National Institute of Mental Health. www.stepbd.org/research/

Drug brand names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

Dr. Post is a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Astra-Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Elan Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Shire Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma.

1. Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. The impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation on 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:612-16.

2. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1252-62.

3. Ghaemi S, El-Mallakh R, Baldassano CF, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar depression: Long-term outcome (abstract). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

4. Sachs GS. Mood stabilizers alone vs.mood stabilizers plus antidepressant in bipolar depression (symposium). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

5. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.

6. Tohen M, Vieta E, Ketter TA, et al. Acute and long-term efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for bipolar depression (abstract). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

7. Calabrese JR, Macfadden W, McCoy R, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine in bipolar depression (abstract). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

8. Post RM, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, et al. Presentations of depression in bipolar illness. Clin Neurosci Res 2002a;2:142-57.

9. Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. A re-evaluation of the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression: data from the Stanley Bipolar Treatment Network. Bipolar Disord 2003a;5:396-406.

10. Post RM, Speer AM, Leverich GS. Bipolar illness: Which critical treatment issues need studying? Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 2003b;2:24-30.

11. Goodwin GM. Bipolar disorder: is psychiatry’s Cinderella starting to get out a little more? Acta Neuropsychiatry 2000;12:105.-

12. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting the course of bipolar disorder. Current Review of Mood and Anxiety Disorders 1996;1:48-61.

13. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting of affective disorders. CNS Spectrums 1998;3:21-37.

14. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:1028-42.

15. Post RM, Speer AM, Obrocea GV, Leverich GS. Acute and prophylactic effects of anticonvulsants in bipolar depression. Clin Neurosci Res 2002;2:228-51.

16. Post RM, Speer AM. A brief history of anticonvulsant use in affective disorders. In: Trimble MR, Schmitz B (eds). Seizures, affective disorders and anticonvulsant drugs Surrey, UK: Clarius Press 2002;53:81.-

17. Post RM, Speer AM, Leverich GS. Complex combination therapy: the evolution toward rational polypharmacy in lithium-resistant bipolar illness, In: Akiskal H, Tohen M (eds). 50 years: the psychopharmacology of bipolar illness London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 2004 (in press).

18. Post RM, Altshuler LL. Mood disorders: treatment of bipolar disorders. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (eds). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (8th ed) New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004 (in press).

Psychiatrists in the trenches are not alone in being unsure how to treat breakthrough bipolar depression. No panelist or other expert attending a recent American College of Neuropsychopharmacology symposium could definitively recommend:

- when to add an antidepressant to mood-stabilizer therapy

- whether to discontinue antidepressants after bipolar depression is stabilized.

Until controlled trials address these issues, we must use limited evidence to treat patients with bipolar depression. To help you meet this challenge, this article offers provisional suggestions based on recent published and unpublished reports.

Evidence for continuing

No published, randomized studies have examined how long to continue antidepressants after bipolar depression has stabilized. Until recently, conventional wisdom has been to discontinue antidepressants as soon as possible because of worries about antidepressant-induced mania. Then two case-controlled studies—one retrospective and one prospective—challenged that assumption.

Figure Reduced relapse rates in patients whose antidepressants were continued

In a prospective case-controlled study, patients with bipolar disorder who continued antidepressant treatment for 6 to 12 months or >12 months after depressive episode remission had lower relapse rates than those who discontinued antidepressants within 6 months.

Source: Reprinted with permission from reference 2. Copyright 2003. American Psychiatric AssociationUsing similar methodologies, Altshuler et al1,2 examined bipolar patients who remained in remission for 6 weeks on mood stabilizers plus adjunctive antidepressants. Those who continued the antidepressants were less likely to relapse into depression (without an increase in manic episodes) than those whose antidepressants were discontinued (Figure).

Relapse rates in the first study1 were 35% at 1 year in those who continued antidepressants and 68% in those who did not. In the second study,2 36% and 70% of patients, respectively, had relapsed at 1 year. In the latter study, those who continued to take antidepressants for at least 6 months—instead of at least 12 months—had intermediate depressive relapse rates (53% for 6 months vs. 24% for 12 months).

When interpreting these data, keep several caveats in mind. For one, patients were not randomly assigned to continue or discontinue antidepressants but were designated by patient and clinician choice. When comparing the two patient groups, however, the authors found no inherent differences in illness characteristics that might have biased the results.

More importantly, few patients initially treated with antidepressant augmentation responded well and remained in remission. In the prospective study, 549 of 1,078 patients in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network received an antidepressant for breakthrough depressive symptoms.2 Only 189 remained on antidepressants for 2 months, and only 84 (15%) of the original population remained in remission for 2 months.

Summary. A small subgroup of patients appears to respond well to antidepressants and sustains this response for 6 to 8 weeks. For this subset, continuing antidepressant therapy would appear to be an appropriate strategy, based on:

- a significantly reduced risk for depressive relapse

- no increased risk of switching to mania, which is the usual reason to terminate antidepressants early.

Subsequent evidence

One needs to assess these observations in light of an interim analysis reported halfway through a small, open, randomized study. Ghaemi et al3 found no significant difference in outcomes—regardless of rapid-cycling status—among 14 bipolar patients who remained on antidepressants and 19 who discontinued across an average 60 and 50 weeks, respectively.

Table

Evidence on continuing antidepressants in breakthrough bipolar depression

| Study | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Altshuler et al 1 | Retrospective, case-control, 39 patients (1 year) | Relapse rates: 35% in patients who continued antidepressants after mood stabilization and and 68% in those who did not; study included no rapid-cyclers |

| Altshuler et al 2 | Prospective, case control 84 patients (1 year) | Relapse rates: 36% in patients who continued antidepressants after mood stabilization and 70% in those who did not; study included no rapid cyclers |

| Ghaemi et al 3 (unpublished) | Open, randomized 33 patients (approx. 1 yr) | Relapse rate: 50% within 20 weeks, whether or not patients continued antidepressants; one-third of patients were rapid cyclers |

A survival analysis initially suggested some benefit for continuing antidepressants, but this disappeared when the authors adjusted for potential confounding factors—which was not done in the Altshuler et al studies. Patients receiving short-term or long-term antidepressants had a similar number of depressive episodes per year (1.00 vs. 0.75 episodes/year, respectively). For some reason, nonrapid-cycling patients showed greater depressive morbidity than those with rapid cycling.

Rapid cyclers comprised 30% of patients who continued antidepressants and 37% of those who discontinued. This may explain the 50% relapse rate within 20 weeks in both groups. By comparison, the Altshuler et al studies included no rapid cyclers.1,2 More details on this unpublished data are expected.

Are antidepressants the answer?

The high relapse rate in patients taking mood stabilizers—with or without an antidepressant—and the Ghaemi et al data3 suggest that we need alternate antidepressant approaches to bipolar depression. Potential regimens—anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics, and other agents—merit further study. So far the evidence is mixed, and the most effective approaches are not well-delineated.

Anticonvulsants. Sachs et al4 reported that adding lamotrigine or lamotrigine plus an antidepressant to mood stabilizer therapy did not appear more effective in treating bipolar depression than simply maintaining the mood stabilizers.

Similarly, a small randomized, double-blind study in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) was stopped early because of low total response. Adjunctive lamotrigine (24%) and inositol (17%) appeared more effective than risperidone (5%) for refractory bipolar depression.

Antipsychotics. In an 8-week randomized trial by Tohen et al,5 833 patients with moderate to severe bipolar I depression were treated with olanzapine, olanzapine plus fluoxetine, or placebo. Core depression symptoms improved significantly more with olanzapine alone or with fluoxetine compared with placebo, as measured by mean changes in the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

In a 6-month open trial, 192 patients whose bipolar I depression remitted with any of the three treatments6 continued olanzapine and then, if needed after the first week, the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC). Nearly two-thirds of patients (62%) remained without a depressive recurrence, and 94% remained without a manic recurrence while taking the OFC. These unpublished data indicate that the OFC provided greater prophylactic antimanic than antidepressant effects.

Calabrese et al7 recently presented unpublished data comparing the effects of quetiapine monotherapy, 300 or 600 mg/d, with placebo in patients with bipolar depression. Beginning in the first week of treatment, both quetiapine dosages produced significantly greater antidepressant, antianxiety, and anti-insomnia effects than placebo (P < 0.001). Remission rates with both dosages were >50%.

Summary. These first controlled studies of atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression suggest that this drug class may have antidepressant as well as their demonstrated antimanic effects.

Recommendations—for now

Controlled clinical trials have not been conducted, and the evidence on using adjunctive antidepressants in bipolar depression is ambiguous.8-11 As a result, it is unclear when or how long to use antidepressants, and many of the inferences and suggestions in this paper remain highly provisional.

Initiating antidepressants. My personal treatment guidelines—and those of many other clinicians—are to use the unimodal antidepressants to augment mood stabilizers in bipolar patients experiencing breakthrough depression, as long as they have not had:

- ultra-rapid cycling (>4 episodes/week)

- antidepressant-induced cycle acceleration

- or multiple episodes of antidepressant-induced mania, despite co-treatment with mood stabilizers.

If any of these variables is present, I would instead add another mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic.

Continuing antidepressants. If the patient remains stable for 2 months after the antidepressant is added—with no depression or manic occurrence—I would continue the antidepressant indefinitely, based on the Altshuler et al data.12

Mood charting.I also recommend that clinicians help patients develop an individual method for mood charting, such as that used in the National Institute of Mental Health Life Chart Method (NIMH-LCM)12,13 or the STEP-BD program.14 Goals of the 5-year STEP-BD are to:

- determine the most effective treatments and relapse prevention strategies for bipolar disorder

- evaluate the psychotropic benefit of anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics, cholinesterase inhibitors, and neurotransmitter precursors

- determine the benefit of psychotropic combinations.

Mood charts can provide a retrospective and prospective overview of a patient’s illness course and response to medications. Compared with patient recall, mood charts help clinicians evaluate more precisely the risk of switching and the risks and benefits of starting, continuing, or discontinuing antidepressants. Mood charts may be your most effective tool for managing a patient’s bipolar depression and achieving and maintaining long-term remission.

Summary. In the absence of consensus or guidelines for treating bipolar depression, I suggest:

- a conservative approach—ie, no changes in medication—when the patient remains well on a given regimen

- an aggressive—if not radical—series of treatments and revisions when the illness course remains problematic.

Many medication classes and adjunctive strategies are available for treating bipolar illness.15-18 I recommend that you continue to systematically explore adjunctive treatments and combinations until the patient improves or—even better—attains remission. Good response can be achieved—even in treatment-refractory patients ill for long periods or with recurrent bipolar depression—although complex combination therapy is often required.

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health-Life Chart Method. Retrospective and prospective mood-tracking charts for patients with bipolar disorder. www.bipolarnews.org

- Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Depression (STEP-BD). National Institute of Mental Health. www.stepbd.org/research/

Drug brand names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

Dr. Post is a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Astra-Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Elan Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Shire Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma.

Psychiatrists in the trenches are not alone in being unsure how to treat breakthrough bipolar depression. No panelist or other expert attending a recent American College of Neuropsychopharmacology symposium could definitively recommend:

- when to add an antidepressant to mood-stabilizer therapy

- whether to discontinue antidepressants after bipolar depression is stabilized.

Until controlled trials address these issues, we must use limited evidence to treat patients with bipolar depression. To help you meet this challenge, this article offers provisional suggestions based on recent published and unpublished reports.

Evidence for continuing

No published, randomized studies have examined how long to continue antidepressants after bipolar depression has stabilized. Until recently, conventional wisdom has been to discontinue antidepressants as soon as possible because of worries about antidepressant-induced mania. Then two case-controlled studies—one retrospective and one prospective—challenged that assumption.

Figure Reduced relapse rates in patients whose antidepressants were continued

In a prospective case-controlled study, patients with bipolar disorder who continued antidepressant treatment for 6 to 12 months or >12 months after depressive episode remission had lower relapse rates than those who discontinued antidepressants within 6 months.

Source: Reprinted with permission from reference 2. Copyright 2003. American Psychiatric AssociationUsing similar methodologies, Altshuler et al1,2 examined bipolar patients who remained in remission for 6 weeks on mood stabilizers plus adjunctive antidepressants. Those who continued the antidepressants were less likely to relapse into depression (without an increase in manic episodes) than those whose antidepressants were discontinued (Figure).

Relapse rates in the first study1 were 35% at 1 year in those who continued antidepressants and 68% in those who did not. In the second study,2 36% and 70% of patients, respectively, had relapsed at 1 year. In the latter study, those who continued to take antidepressants for at least 6 months—instead of at least 12 months—had intermediate depressive relapse rates (53% for 6 months vs. 24% for 12 months).

When interpreting these data, keep several caveats in mind. For one, patients were not randomly assigned to continue or discontinue antidepressants but were designated by patient and clinician choice. When comparing the two patient groups, however, the authors found no inherent differences in illness characteristics that might have biased the results.

More importantly, few patients initially treated with antidepressant augmentation responded well and remained in remission. In the prospective study, 549 of 1,078 patients in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network received an antidepressant for breakthrough depressive symptoms.2 Only 189 remained on antidepressants for 2 months, and only 84 (15%) of the original population remained in remission for 2 months.

Summary. A small subgroup of patients appears to respond well to antidepressants and sustains this response for 6 to 8 weeks. For this subset, continuing antidepressant therapy would appear to be an appropriate strategy, based on:

- a significantly reduced risk for depressive relapse

- no increased risk of switching to mania, which is the usual reason to terminate antidepressants early.

Subsequent evidence

One needs to assess these observations in light of an interim analysis reported halfway through a small, open, randomized study. Ghaemi et al3 found no significant difference in outcomes—regardless of rapid-cycling status—among 14 bipolar patients who remained on antidepressants and 19 who discontinued across an average 60 and 50 weeks, respectively.

Table

Evidence on continuing antidepressants in breakthrough bipolar depression

| Study | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Altshuler et al 1 | Retrospective, case-control, 39 patients (1 year) | Relapse rates: 35% in patients who continued antidepressants after mood stabilization and and 68% in those who did not; study included no rapid-cyclers |

| Altshuler et al 2 | Prospective, case control 84 patients (1 year) | Relapse rates: 36% in patients who continued antidepressants after mood stabilization and 70% in those who did not; study included no rapid cyclers |

| Ghaemi et al 3 (unpublished) | Open, randomized 33 patients (approx. 1 yr) | Relapse rate: 50% within 20 weeks, whether or not patients continued antidepressants; one-third of patients were rapid cyclers |

A survival analysis initially suggested some benefit for continuing antidepressants, but this disappeared when the authors adjusted for potential confounding factors—which was not done in the Altshuler et al studies. Patients receiving short-term or long-term antidepressants had a similar number of depressive episodes per year (1.00 vs. 0.75 episodes/year, respectively). For some reason, nonrapid-cycling patients showed greater depressive morbidity than those with rapid cycling.

Rapid cyclers comprised 30% of patients who continued antidepressants and 37% of those who discontinued. This may explain the 50% relapse rate within 20 weeks in both groups. By comparison, the Altshuler et al studies included no rapid cyclers.1,2 More details on this unpublished data are expected.

Are antidepressants the answer?

The high relapse rate in patients taking mood stabilizers—with or without an antidepressant—and the Ghaemi et al data3 suggest that we need alternate antidepressant approaches to bipolar depression. Potential regimens—anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics, and other agents—merit further study. So far the evidence is mixed, and the most effective approaches are not well-delineated.

Anticonvulsants. Sachs et al4 reported that adding lamotrigine or lamotrigine plus an antidepressant to mood stabilizer therapy did not appear more effective in treating bipolar depression than simply maintaining the mood stabilizers.

Similarly, a small randomized, double-blind study in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) was stopped early because of low total response. Adjunctive lamotrigine (24%) and inositol (17%) appeared more effective than risperidone (5%) for refractory bipolar depression.

Antipsychotics. In an 8-week randomized trial by Tohen et al,5 833 patients with moderate to severe bipolar I depression were treated with olanzapine, olanzapine plus fluoxetine, or placebo. Core depression symptoms improved significantly more with olanzapine alone or with fluoxetine compared with placebo, as measured by mean changes in the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

In a 6-month open trial, 192 patients whose bipolar I depression remitted with any of the three treatments6 continued olanzapine and then, if needed after the first week, the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC). Nearly two-thirds of patients (62%) remained without a depressive recurrence, and 94% remained without a manic recurrence while taking the OFC. These unpublished data indicate that the OFC provided greater prophylactic antimanic than antidepressant effects.

Calabrese et al7 recently presented unpublished data comparing the effects of quetiapine monotherapy, 300 or 600 mg/d, with placebo in patients with bipolar depression. Beginning in the first week of treatment, both quetiapine dosages produced significantly greater antidepressant, antianxiety, and anti-insomnia effects than placebo (P < 0.001). Remission rates with both dosages were >50%.

Summary. These first controlled studies of atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression suggest that this drug class may have antidepressant as well as their demonstrated antimanic effects.

Recommendations—for now

Controlled clinical trials have not been conducted, and the evidence on using adjunctive antidepressants in bipolar depression is ambiguous.8-11 As a result, it is unclear when or how long to use antidepressants, and many of the inferences and suggestions in this paper remain highly provisional.

Initiating antidepressants. My personal treatment guidelines—and those of many other clinicians—are to use the unimodal antidepressants to augment mood stabilizers in bipolar patients experiencing breakthrough depression, as long as they have not had:

- ultra-rapid cycling (>4 episodes/week)

- antidepressant-induced cycle acceleration

- or multiple episodes of antidepressant-induced mania, despite co-treatment with mood stabilizers.

If any of these variables is present, I would instead add another mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic.

Continuing antidepressants. If the patient remains stable for 2 months after the antidepressant is added—with no depression or manic occurrence—I would continue the antidepressant indefinitely, based on the Altshuler et al data.12

Mood charting.I also recommend that clinicians help patients develop an individual method for mood charting, such as that used in the National Institute of Mental Health Life Chart Method (NIMH-LCM)12,13 or the STEP-BD program.14 Goals of the 5-year STEP-BD are to:

- determine the most effective treatments and relapse prevention strategies for bipolar disorder

- evaluate the psychotropic benefit of anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics, cholinesterase inhibitors, and neurotransmitter precursors

- determine the benefit of psychotropic combinations.

Mood charts can provide a retrospective and prospective overview of a patient’s illness course and response to medications. Compared with patient recall, mood charts help clinicians evaluate more precisely the risk of switching and the risks and benefits of starting, continuing, or discontinuing antidepressants. Mood charts may be your most effective tool for managing a patient’s bipolar depression and achieving and maintaining long-term remission.

Summary. In the absence of consensus or guidelines for treating bipolar depression, I suggest:

- a conservative approach—ie, no changes in medication—when the patient remains well on a given regimen

- an aggressive—if not radical—series of treatments and revisions when the illness course remains problematic.

Many medication classes and adjunctive strategies are available for treating bipolar illness.15-18 I recommend that you continue to systematically explore adjunctive treatments and combinations until the patient improves or—even better—attains remission. Good response can be achieved—even in treatment-refractory patients ill for long periods or with recurrent bipolar depression—although complex combination therapy is often required.

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health-Life Chart Method. Retrospective and prospective mood-tracking charts for patients with bipolar disorder. www.bipolarnews.org

- Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Depression (STEP-BD). National Institute of Mental Health. www.stepbd.org/research/

Drug brand names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

Dr. Post is a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Astra-Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Elan Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Shire Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma.

1. Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. The impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation on 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:612-16.

2. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1252-62.

3. Ghaemi S, El-Mallakh R, Baldassano CF, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar depression: Long-term outcome (abstract). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

4. Sachs GS. Mood stabilizers alone vs.mood stabilizers plus antidepressant in bipolar depression (symposium). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

5. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.

6. Tohen M, Vieta E, Ketter TA, et al. Acute and long-term efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for bipolar depression (abstract). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

7. Calabrese JR, Macfadden W, McCoy R, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine in bipolar depression (abstract). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

8. Post RM, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, et al. Presentations of depression in bipolar illness. Clin Neurosci Res 2002a;2:142-57.

9. Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. A re-evaluation of the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression: data from the Stanley Bipolar Treatment Network. Bipolar Disord 2003a;5:396-406.

10. Post RM, Speer AM, Leverich GS. Bipolar illness: Which critical treatment issues need studying? Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 2003b;2:24-30.

11. Goodwin GM. Bipolar disorder: is psychiatry’s Cinderella starting to get out a little more? Acta Neuropsychiatry 2000;12:105.-

12. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting the course of bipolar disorder. Current Review of Mood and Anxiety Disorders 1996;1:48-61.

13. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting of affective disorders. CNS Spectrums 1998;3:21-37.

14. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:1028-42.

15. Post RM, Speer AM, Obrocea GV, Leverich GS. Acute and prophylactic effects of anticonvulsants in bipolar depression. Clin Neurosci Res 2002;2:228-51.

16. Post RM, Speer AM. A brief history of anticonvulsant use in affective disorders. In: Trimble MR, Schmitz B (eds). Seizures, affective disorders and anticonvulsant drugs Surrey, UK: Clarius Press 2002;53:81.-

17. Post RM, Speer AM, Leverich GS. Complex combination therapy: the evolution toward rational polypharmacy in lithium-resistant bipolar illness, In: Akiskal H, Tohen M (eds). 50 years: the psychopharmacology of bipolar illness London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 2004 (in press).

18. Post RM, Altshuler LL. Mood disorders: treatment of bipolar disorders. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (eds). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (8th ed) New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004 (in press).

1. Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. The impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation on 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:612-16.

2. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1252-62.

3. Ghaemi S, El-Mallakh R, Baldassano CF, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar depression: Long-term outcome (abstract). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

4. Sachs GS. Mood stabilizers alone vs.mood stabilizers plus antidepressant in bipolar depression (symposium). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

5. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.

6. Tohen M, Vieta E, Ketter TA, et al. Acute and long-term efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for bipolar depression (abstract). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2003.

7. Calabrese JR, Macfadden W, McCoy R, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine in bipolar depression (abstract). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

8. Post RM, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, et al. Presentations of depression in bipolar illness. Clin Neurosci Res 2002a;2:142-57.

9. Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. A re-evaluation of the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression: data from the Stanley Bipolar Treatment Network. Bipolar Disord 2003a;5:396-406.

10. Post RM, Speer AM, Leverich GS. Bipolar illness: Which critical treatment issues need studying? Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 2003b;2:24-30.

11. Goodwin GM. Bipolar disorder: is psychiatry’s Cinderella starting to get out a little more? Acta Neuropsychiatry 2000;12:105.-

12. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting the course of bipolar disorder. Current Review of Mood and Anxiety Disorders 1996;1:48-61.

13. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting of affective disorders. CNS Spectrums 1998;3:21-37.

14. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:1028-42.

15. Post RM, Speer AM, Obrocea GV, Leverich GS. Acute and prophylactic effects of anticonvulsants in bipolar depression. Clin Neurosci Res 2002;2:228-51.

16. Post RM, Speer AM. A brief history of anticonvulsant use in affective disorders. In: Trimble MR, Schmitz B (eds). Seizures, affective disorders and anticonvulsant drugs Surrey, UK: Clarius Press 2002;53:81.-

17. Post RM, Speer AM, Leverich GS. Complex combination therapy: the evolution toward rational polypharmacy in lithium-resistant bipolar illness, In: Akiskal H, Tohen M (eds). 50 years: the psychopharmacology of bipolar illness London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 2004 (in press).

18. Post RM, Altshuler LL. Mood disorders: treatment of bipolar disorders. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (eds). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (8th ed) New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004 (in press).