User login

Case

A 23-year-old Hispanic woman with no past medical history is brought to the ED for the second time in one day. On her first presentation, which was for a fever and a headache, meningitis was excluded with normal laboratory tests that included a lumbar puncture. She was administered acetaminophen for fever and pain control, and was discharged with a diagnosis of viral illness. On this second visit, 10 hours after being discharged, she presented because her family noted convulsions that began 3 hours after taking an herbal headache remedy given to her by a naturopath.

The patient arrived to the ED with a persistent seizure that terminated following administration of 2 mg of lorazepam. Her initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 115/51 mm Hg; heart rate, 121 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; temperature, 97.6oF. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 100% with 2 L of O2 administered via nasal cannula. Her neurological examination was significant for a depressed mental status, pupils that were 6 mm and minimally reactive, clonus, and hyperreflexia. Repeat laboratory evaluation found a leukocytosis of 22.0 x 103/µL, serum bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 22 with a normal serum lactate.

What is the differential diagnosis of this patient?

The history of medicinal plant ingestion raises the possibility of a toxicologic etiology. However, because the patient took the “medication” to treat another disorder, a search for an alternate cause should be performed. The differential diagnosis of a toxin-induced seizure is broad and includes pharmaceuticals (eg, tramadol, antihistamines), which may be surreptitiously added to herbal medication to assure efficacy. Plants associated with seizures include those containing antimuscarinic tropane alkaloids such as Jimsonweed (though a rare side effect from this plant product) or the water hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Contaminants of the plant itself may include pesticides such as organophosphates.

Although unlikely in a 21 year old, withdrawal from benzodiazepines, ethanol, baclofen, or gamma hydroxybutyrate are other possible etiologies. In addition to pharmaceutical and plant-derived causes, carbon monoxide poisoning should be a consideration in any patient with headache and flu-like illness.

This patient also presented with a constellation of other findings that included hyperreflexia, clonus, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Together these signs are expected in patients with serotonin toxicity (also referred to as serotonin syndrome), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, exogenous thyrotoxicosis, and lithium poisoning.

Case Continuation

The naturopathic practitioner arrived at the ED concerned about the patient, informing the ED team that she had given the patient 2 ounces of ayahuasca tea.

What is ayahuasca? What is the mechanism by which it exerts toxic effects?

Ayahuasca is a plant-derived psychotropic beverage that is used for religious purposes by members of two Brazilian churches—Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (UDV) and Santo Daime. The ayahuasca beverage consists of two pharmacologically active compounds that together, but not individually, are psychoactive. The desired active effects for church participants include hallucinations, and vomiting to bring about a “religious purge.”1

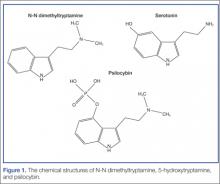

Ayahuasca is prepared by combining two plants indigenous to the Amazon Basin area: Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana. B caapi contains the β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These alkaloids act as reversible inhibitors of the monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) enzyme. The bark and stems of B caapi are boiled along with either P viridis or D cabrerana, both of which contain the potent hallucinogen N-N dimethyltryptamine (DMT).2 Normally, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically metabolized by MAO-A. However, when taken in the presence of the B caapi-derived MAO-A–inhibiting harmine alkaloids, DMT reaches the systemic circulation and produces its clinical effects.3

What are the clinical findings of serotonin toxicity?

Serotonin toxicity is a collection of clinical findings that fall under three main categories: autonomic hyperactivity, altered mental status, and muscle rigidity.5 The autonomic findings may include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, shivering, diaphoresis, or mydriasis. Altered mental status ranges from mild agitation and hypervigilance to agitated delirium to obtundation. Other neurological findings may include tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, or seizures. The onset of these signs is rapid, usually occurring within minutes after exposure to one or more serotonergic compounds. Although rare, severe serotonin toxicity may be associated with hypotension and shock, leading to death.4

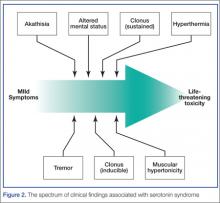

The diagnosis of serotonin toxicity is based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Diagnostic criteria that have been suggested include the following: (1) a recent addition or increase in a known serotonergic agent; (2) absence of other possible etiologies; (3) no recent increase or addition of a neuroleptic agent (suggesting neuroleptic malignant syndrome); and/or (4) at least 3 of the following symptoms—mental status changes, myoclonus, agitation, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, incoordination, fever5 (Figure 2).

How should this patient be managed?

The management of serotonin toxicity is primarily supportive with aggressive control of hyperthermia and autonomic instability. The precipitating xenobiotic agent should be immediately discontinued. In general, treatment with intravenous fluids, cooling measures, benzodiazepines, and a nonspecific 5-HT antagonist such as cyproheptadine should greatly improve the patient’s clinical status. Patients with severe toxicity may require induced paralysis and intubation.4 It is not clear in this case if the serotonin hyperactivation was due to the DMT (5-HT2A is associated with serotonin toxicity) or another serotonergic agent (eg, dextromethorphan from a cough and cold preparation) in combination with the MAO-inhibiting harmine alkaloids.

What is the availability of ayahuasca in the United States? How is it used in its nonherbal form?

...[Ayahuasca] is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches. Many clinicians are becoming increasingly familiar with this herbal preparation since the recreational use of ayahuasca is gaining popularity in the United States. Internet fora with information on how to safely use ayahuasca, such as avoiding aged cheeses, are becoming more prevalent.7 A recent article in the New York Times described an ayahuasca gathering in Brooklyn, New York, where participants use the herb in a communal fashion.8 This herbal product is also associated with the Hollywood social scene and has received celebrity endorsements.8

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of people in the United States who have used DMT has gone up almost every year since 2006, from an estimated 688,000 in 2006 to 1,475,000 in 2012.9 When used alone (not as ayahuasca), DMT is almost exclusively insufflated as a nasal snuff, bypassing hepatic elimination. It has an onset of around 45 seconds and a duration of 5 to 10 minutes. Insufflating DMT was historically referred to as a “businessman’s trip” because users were able to have a brief hallucinogenic experience on a lunch break and recover rapidly to perform their normal work.10

International law declares that DMT is an illegal substance and its importation is banned. However, its use for religious purposes, as is allowed for mescaline found in peyote, remains controversial.7 The UDV brought suit in United States federal court to prevent interference with the church’s use of ayahuasca during religious ceremonies based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This act states that the government should not cause substantial imposition on religious practices in the absence of a compelling government interest. The court sided with the UDV, finding that the government had not sufficiently proved the alleged health risks posed by ayahuasca and could not show a substantial risk that the drug would be abused recreationally.11 Thus it is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches.

Ayahuasca is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Many different types of preparations with different ingredients as well as different concentrations may exist, and clinical variability should be expected. Understanding that ayahuasca is capable of inhibiting MAO is important in order to avoid foods and medications, such as dextromethorphan, that may trigger adverse effects.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by an additional seizure 12 hours after her initial presentation. By 36 hours she was back to her baseline mental status with a normal neurological examination.

Dr Fil is a senior fellow in medical toxicology at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Gable RS. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction. 2007;102(1):24-34.

- Riba J, McIlhenny EH, Valle M, Bouso JC, Barker SA. Metabolism and Disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids after oral administration of ayahuasca. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7-8):610-616.

- Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(1):73-83

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11);1112-1120.

- Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):6;705-713.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

- Erowid. Ayahuasca Vault. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Morris B. Ayahuasca: a strong cup of tea. New York Times. June 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/fashion/ayahuasca-a-strong-cup-of-tea.html. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Quintanilla D. DMT: Hallucinogenic Drug Used in Shamanic Rituals Goes Mainstream. 10 Dec 2013. Available: http://www.opposingviews.com/i/health/dmt-hallucinogenic-drug-used-shamanic-rituals-goes-mainstream. Last accessed 11/14/14.

- Haroz R, Greenberg MI. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1259-1276.

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 US 418 (2006). Available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=7036734975431570669&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 25, 2014.

Case

A 23-year-old Hispanic woman with no past medical history is brought to the ED for the second time in one day. On her first presentation, which was for a fever and a headache, meningitis was excluded with normal laboratory tests that included a lumbar puncture. She was administered acetaminophen for fever and pain control, and was discharged with a diagnosis of viral illness. On this second visit, 10 hours after being discharged, she presented because her family noted convulsions that began 3 hours after taking an herbal headache remedy given to her by a naturopath.

The patient arrived to the ED with a persistent seizure that terminated following administration of 2 mg of lorazepam. Her initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 115/51 mm Hg; heart rate, 121 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; temperature, 97.6oF. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 100% with 2 L of O2 administered via nasal cannula. Her neurological examination was significant for a depressed mental status, pupils that were 6 mm and minimally reactive, clonus, and hyperreflexia. Repeat laboratory evaluation found a leukocytosis of 22.0 x 103/µL, serum bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 22 with a normal serum lactate.

What is the differential diagnosis of this patient?

The history of medicinal plant ingestion raises the possibility of a toxicologic etiology. However, because the patient took the “medication” to treat another disorder, a search for an alternate cause should be performed. The differential diagnosis of a toxin-induced seizure is broad and includes pharmaceuticals (eg, tramadol, antihistamines), which may be surreptitiously added to herbal medication to assure efficacy. Plants associated with seizures include those containing antimuscarinic tropane alkaloids such as Jimsonweed (though a rare side effect from this plant product) or the water hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Contaminants of the plant itself may include pesticides such as organophosphates.

Although unlikely in a 21 year old, withdrawal from benzodiazepines, ethanol, baclofen, or gamma hydroxybutyrate are other possible etiologies. In addition to pharmaceutical and plant-derived causes, carbon monoxide poisoning should be a consideration in any patient with headache and flu-like illness.

This patient also presented with a constellation of other findings that included hyperreflexia, clonus, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Together these signs are expected in patients with serotonin toxicity (also referred to as serotonin syndrome), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, exogenous thyrotoxicosis, and lithium poisoning.

Case Continuation

The naturopathic practitioner arrived at the ED concerned about the patient, informing the ED team that she had given the patient 2 ounces of ayahuasca tea.

What is ayahuasca? What is the mechanism by which it exerts toxic effects?

Ayahuasca is a plant-derived psychotropic beverage that is used for religious purposes by members of two Brazilian churches—Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (UDV) and Santo Daime. The ayahuasca beverage consists of two pharmacologically active compounds that together, but not individually, are psychoactive. The desired active effects for church participants include hallucinations, and vomiting to bring about a “religious purge.”1

Ayahuasca is prepared by combining two plants indigenous to the Amazon Basin area: Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana. B caapi contains the β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These alkaloids act as reversible inhibitors of the monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) enzyme. The bark and stems of B caapi are boiled along with either P viridis or D cabrerana, both of which contain the potent hallucinogen N-N dimethyltryptamine (DMT).2 Normally, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically metabolized by MAO-A. However, when taken in the presence of the B caapi-derived MAO-A–inhibiting harmine alkaloids, DMT reaches the systemic circulation and produces its clinical effects.3

What are the clinical findings of serotonin toxicity?

Serotonin toxicity is a collection of clinical findings that fall under three main categories: autonomic hyperactivity, altered mental status, and muscle rigidity.5 The autonomic findings may include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, shivering, diaphoresis, or mydriasis. Altered mental status ranges from mild agitation and hypervigilance to agitated delirium to obtundation. Other neurological findings may include tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, or seizures. The onset of these signs is rapid, usually occurring within minutes after exposure to one or more serotonergic compounds. Although rare, severe serotonin toxicity may be associated with hypotension and shock, leading to death.4

The diagnosis of serotonin toxicity is based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Diagnostic criteria that have been suggested include the following: (1) a recent addition or increase in a known serotonergic agent; (2) absence of other possible etiologies; (3) no recent increase or addition of a neuroleptic agent (suggesting neuroleptic malignant syndrome); and/or (4) at least 3 of the following symptoms—mental status changes, myoclonus, agitation, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, incoordination, fever5 (Figure 2).

How should this patient be managed?

The management of serotonin toxicity is primarily supportive with aggressive control of hyperthermia and autonomic instability. The precipitating xenobiotic agent should be immediately discontinued. In general, treatment with intravenous fluids, cooling measures, benzodiazepines, and a nonspecific 5-HT antagonist such as cyproheptadine should greatly improve the patient’s clinical status. Patients with severe toxicity may require induced paralysis and intubation.4 It is not clear in this case if the serotonin hyperactivation was due to the DMT (5-HT2A is associated with serotonin toxicity) or another serotonergic agent (eg, dextromethorphan from a cough and cold preparation) in combination with the MAO-inhibiting harmine alkaloids.

What is the availability of ayahuasca in the United States? How is it used in its nonherbal form?

...[Ayahuasca] is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches. Many clinicians are becoming increasingly familiar with this herbal preparation since the recreational use of ayahuasca is gaining popularity in the United States. Internet fora with information on how to safely use ayahuasca, such as avoiding aged cheeses, are becoming more prevalent.7 A recent article in the New York Times described an ayahuasca gathering in Brooklyn, New York, where participants use the herb in a communal fashion.8 This herbal product is also associated with the Hollywood social scene and has received celebrity endorsements.8

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of people in the United States who have used DMT has gone up almost every year since 2006, from an estimated 688,000 in 2006 to 1,475,000 in 2012.9 When used alone (not as ayahuasca), DMT is almost exclusively insufflated as a nasal snuff, bypassing hepatic elimination. It has an onset of around 45 seconds and a duration of 5 to 10 minutes. Insufflating DMT was historically referred to as a “businessman’s trip” because users were able to have a brief hallucinogenic experience on a lunch break and recover rapidly to perform their normal work.10

International law declares that DMT is an illegal substance and its importation is banned. However, its use for religious purposes, as is allowed for mescaline found in peyote, remains controversial.7 The UDV brought suit in United States federal court to prevent interference with the church’s use of ayahuasca during religious ceremonies based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This act states that the government should not cause substantial imposition on religious practices in the absence of a compelling government interest. The court sided with the UDV, finding that the government had not sufficiently proved the alleged health risks posed by ayahuasca and could not show a substantial risk that the drug would be abused recreationally.11 Thus it is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches.

Ayahuasca is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Many different types of preparations with different ingredients as well as different concentrations may exist, and clinical variability should be expected. Understanding that ayahuasca is capable of inhibiting MAO is important in order to avoid foods and medications, such as dextromethorphan, that may trigger adverse effects.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by an additional seizure 12 hours after her initial presentation. By 36 hours she was back to her baseline mental status with a normal neurological examination.

Dr Fil is a senior fellow in medical toxicology at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 23-year-old Hispanic woman with no past medical history is brought to the ED for the second time in one day. On her first presentation, which was for a fever and a headache, meningitis was excluded with normal laboratory tests that included a lumbar puncture. She was administered acetaminophen for fever and pain control, and was discharged with a diagnosis of viral illness. On this second visit, 10 hours after being discharged, she presented because her family noted convulsions that began 3 hours after taking an herbal headache remedy given to her by a naturopath.

The patient arrived to the ED with a persistent seizure that terminated following administration of 2 mg of lorazepam. Her initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 115/51 mm Hg; heart rate, 121 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; temperature, 97.6oF. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 100% with 2 L of O2 administered via nasal cannula. Her neurological examination was significant for a depressed mental status, pupils that were 6 mm and minimally reactive, clonus, and hyperreflexia. Repeat laboratory evaluation found a leukocytosis of 22.0 x 103/µL, serum bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 22 with a normal serum lactate.

What is the differential diagnosis of this patient?

The history of medicinal plant ingestion raises the possibility of a toxicologic etiology. However, because the patient took the “medication” to treat another disorder, a search for an alternate cause should be performed. The differential diagnosis of a toxin-induced seizure is broad and includes pharmaceuticals (eg, tramadol, antihistamines), which may be surreptitiously added to herbal medication to assure efficacy. Plants associated with seizures include those containing antimuscarinic tropane alkaloids such as Jimsonweed (though a rare side effect from this plant product) or the water hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Contaminants of the plant itself may include pesticides such as organophosphates.

Although unlikely in a 21 year old, withdrawal from benzodiazepines, ethanol, baclofen, or gamma hydroxybutyrate are other possible etiologies. In addition to pharmaceutical and plant-derived causes, carbon monoxide poisoning should be a consideration in any patient with headache and flu-like illness.

This patient also presented with a constellation of other findings that included hyperreflexia, clonus, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Together these signs are expected in patients with serotonin toxicity (also referred to as serotonin syndrome), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, exogenous thyrotoxicosis, and lithium poisoning.

Case Continuation

The naturopathic practitioner arrived at the ED concerned about the patient, informing the ED team that she had given the patient 2 ounces of ayahuasca tea.

What is ayahuasca? What is the mechanism by which it exerts toxic effects?

Ayahuasca is a plant-derived psychotropic beverage that is used for religious purposes by members of two Brazilian churches—Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (UDV) and Santo Daime. The ayahuasca beverage consists of two pharmacologically active compounds that together, but not individually, are psychoactive. The desired active effects for church participants include hallucinations, and vomiting to bring about a “religious purge.”1

Ayahuasca is prepared by combining two plants indigenous to the Amazon Basin area: Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana. B caapi contains the β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These alkaloids act as reversible inhibitors of the monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) enzyme. The bark and stems of B caapi are boiled along with either P viridis or D cabrerana, both of which contain the potent hallucinogen N-N dimethyltryptamine (DMT).2 Normally, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically metabolized by MAO-A. However, when taken in the presence of the B caapi-derived MAO-A–inhibiting harmine alkaloids, DMT reaches the systemic circulation and produces its clinical effects.3

What are the clinical findings of serotonin toxicity?

Serotonin toxicity is a collection of clinical findings that fall under three main categories: autonomic hyperactivity, altered mental status, and muscle rigidity.5 The autonomic findings may include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, shivering, diaphoresis, or mydriasis. Altered mental status ranges from mild agitation and hypervigilance to agitated delirium to obtundation. Other neurological findings may include tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, or seizures. The onset of these signs is rapid, usually occurring within minutes after exposure to one or more serotonergic compounds. Although rare, severe serotonin toxicity may be associated with hypotension and shock, leading to death.4

The diagnosis of serotonin toxicity is based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Diagnostic criteria that have been suggested include the following: (1) a recent addition or increase in a known serotonergic agent; (2) absence of other possible etiologies; (3) no recent increase or addition of a neuroleptic agent (suggesting neuroleptic malignant syndrome); and/or (4) at least 3 of the following symptoms—mental status changes, myoclonus, agitation, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, incoordination, fever5 (Figure 2).

How should this patient be managed?

The management of serotonin toxicity is primarily supportive with aggressive control of hyperthermia and autonomic instability. The precipitating xenobiotic agent should be immediately discontinued. In general, treatment with intravenous fluids, cooling measures, benzodiazepines, and a nonspecific 5-HT antagonist such as cyproheptadine should greatly improve the patient’s clinical status. Patients with severe toxicity may require induced paralysis and intubation.4 It is not clear in this case if the serotonin hyperactivation was due to the DMT (5-HT2A is associated with serotonin toxicity) or another serotonergic agent (eg, dextromethorphan from a cough and cold preparation) in combination with the MAO-inhibiting harmine alkaloids.

What is the availability of ayahuasca in the United States? How is it used in its nonherbal form?

...[Ayahuasca] is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches. Many clinicians are becoming increasingly familiar with this herbal preparation since the recreational use of ayahuasca is gaining popularity in the United States. Internet fora with information on how to safely use ayahuasca, such as avoiding aged cheeses, are becoming more prevalent.7 A recent article in the New York Times described an ayahuasca gathering in Brooklyn, New York, where participants use the herb in a communal fashion.8 This herbal product is also associated with the Hollywood social scene and has received celebrity endorsements.8

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of people in the United States who have used DMT has gone up almost every year since 2006, from an estimated 688,000 in 2006 to 1,475,000 in 2012.9 When used alone (not as ayahuasca), DMT is almost exclusively insufflated as a nasal snuff, bypassing hepatic elimination. It has an onset of around 45 seconds and a duration of 5 to 10 minutes. Insufflating DMT was historically referred to as a “businessman’s trip” because users were able to have a brief hallucinogenic experience on a lunch break and recover rapidly to perform their normal work.10

International law declares that DMT is an illegal substance and its importation is banned. However, its use for religious purposes, as is allowed for mescaline found in peyote, remains controversial.7 The UDV brought suit in United States federal court to prevent interference with the church’s use of ayahuasca during religious ceremonies based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This act states that the government should not cause substantial imposition on religious practices in the absence of a compelling government interest. The court sided with the UDV, finding that the government had not sufficiently proved the alleged health risks posed by ayahuasca and could not show a substantial risk that the drug would be abused recreationally.11 Thus it is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches.

Ayahuasca is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Many different types of preparations with different ingredients as well as different concentrations may exist, and clinical variability should be expected. Understanding that ayahuasca is capable of inhibiting MAO is important in order to avoid foods and medications, such as dextromethorphan, that may trigger adverse effects.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by an additional seizure 12 hours after her initial presentation. By 36 hours she was back to her baseline mental status with a normal neurological examination.

Dr Fil is a senior fellow in medical toxicology at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Gable RS. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction. 2007;102(1):24-34.

- Riba J, McIlhenny EH, Valle M, Bouso JC, Barker SA. Metabolism and Disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids after oral administration of ayahuasca. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7-8):610-616.

- Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(1):73-83

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11);1112-1120.

- Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):6;705-713.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

- Erowid. Ayahuasca Vault. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Morris B. Ayahuasca: a strong cup of tea. New York Times. June 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/fashion/ayahuasca-a-strong-cup-of-tea.html. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Quintanilla D. DMT: Hallucinogenic Drug Used in Shamanic Rituals Goes Mainstream. 10 Dec 2013. Available: http://www.opposingviews.com/i/health/dmt-hallucinogenic-drug-used-shamanic-rituals-goes-mainstream. Last accessed 11/14/14.

- Haroz R, Greenberg MI. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1259-1276.

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 US 418 (2006). Available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=7036734975431570669&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Gable RS. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction. 2007;102(1):24-34.

- Riba J, McIlhenny EH, Valle M, Bouso JC, Barker SA. Metabolism and Disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids after oral administration of ayahuasca. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7-8):610-616.

- Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(1):73-83

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11);1112-1120.

- Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):6;705-713.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

- Erowid. Ayahuasca Vault. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Morris B. Ayahuasca: a strong cup of tea. New York Times. June 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/fashion/ayahuasca-a-strong-cup-of-tea.html. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Quintanilla D. DMT: Hallucinogenic Drug Used in Shamanic Rituals Goes Mainstream. 10 Dec 2013. Available: http://www.opposingviews.com/i/health/dmt-hallucinogenic-drug-used-shamanic-rituals-goes-mainstream. Last accessed 11/14/14.

- Haroz R, Greenberg MI. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1259-1276.

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 US 418 (2006). Available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=7036734975431570669&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 25, 2014.