User login

A specialty without a disease: It was a major hangup for the field of hospital medicine in the early days. We’d hurdled many of the traditional barriers to specialty status—research fellowships, textbooks, an active society, a growing body of research, and thousands of practitioners focusing their practice on the hospital setting. However, despite several examples of site-defined specialties like emergency and critical-care medicine, cynics clung to the time-honored need for a specialty to own an organ, or at least a disease.

Early SHM efforts made a strong push to make VTE our disease—both its treatment and, more importantly, its prevention. It was a laudable effort, one that has saved many thousands of lives and limbs. It made sense for hospitalists to tackle VTE; it’s an incapacitating disease that affects many, is largely preventable, and had no strong inpatient advocate. While hematologists were the obvious “owner” of this disease, they were neither available nor able to redesign the inpatient systems of care necessary to thwart this illness. Hospitalists, invested in this issue by consequence of direct care of many at-risk patients and through commitment to improving hospital systems, came to own VTE prevention.

The Next Frontier: Stroke

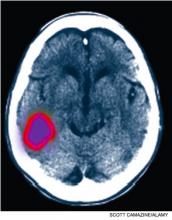

It is time hospitalists apply this experience to the management of an even more incapacitating, largely preventable disease looking for an inpatient steward: stroke. A stroke occurs in the U.S. every 40 seconds, with disabling sequelae that often are avoidable with rapid detection and treatment. This is especially true when we are given the clarion call of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The problem is that most American hospitals are not kingpins of efficiency—the key ingredient of the processes necessary to improve stroke outcomes. Furthermore, while our neurologic colleagues are the obvious group to lead the deployment of stroke QI programs, there just aren’t enough of them to do so.

Hospitalists provide a significant amount of neurologic care. One study notes that TIA and stroke were among the most commonly cared-for diseases by hospitalists.1 This places us in a prime position to take the lead and own this disease in collaboration with our neurology colleagues. Just as with reliable VTE prevention, the key to effective stroke care requires effective systems engineering in conjunction with disease-specific expertise.

Rapid Care for Acute Medical Crisis

EDs are equipped with stroke pathways to efficiently evaluate, triage, scan, and intervene for patients who present with stroke symptoms. While most hospitals have a long way to go to perfect these systems, some hospitals—mostly in large, urban centers—have achieved the appropriate level of ED efficiency. These hospitals are recognized by The Joint Commission accreditation as stroke centers. As a result, patients who present to these hospitals with stroke symptoms often receive thrombolytics—a disease- and life-altering therapy—within the appropriate, but very limited, time window for benefit.

But what happens if that same patient develops those same signs and symptoms in the hospital? Will they get the same level of efficient evaluation, triage, scanning, and intervention that occurs in the ED? This is more than an academic question. Fifteen percent of all strokes are heralded by transient neurologic deficits, so many of the estimated 300,000 annual TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. What’s the reason for the admission? To facilitate the diagnostic workup, monitor for stroke symptoms and apply timely interventions should this occur.

But are we equipped to provide this kind of timely care in the hospital?

Case Study

Let’s take a 70-year-old diabetic male who presents with 45 minutes of aphasia and right-side arm weakness that resolve prior to presentation to the ED. If the patient is hypertensive on admission, the ABCD tool would suggest that he has a risk of stroke that approximates 20% in 90 days.2 Importantly, nearly half of that risk is in the first 48 hours. In other words, he has about a 10% risk of having a stroke in the next two days. Thus, we rightly admit him for monitoring in order to react quickly to any new signs and symptoms.

The problem is that most hospitals don’t have a system to efficiently manage patients who develop new stroke symptoms in the hospital. Does your hospital have an inpatient stroke pathway? That is, for a patient who has stroke onset while already in the hospital:

- Are the nurses aware of stroke signs and symptoms?

- Do nurses have a phone number to call to initiate an evaluation?

- Is there a team with stroke expertise immediately available to respond to those calls?

- Is there a priority path to get the patient promptly transported to the CT scanner for brain imaging with immediate radiology interpretation?

- How fast can thrombolytics be delivered, and is there an inpatient neurologist available 24/7 to assist?

The goal is 25 minutes from first recognition of symptoms to CT scan, and 60 minutes to complete evaluation and commencement of treatment. What percentage of your inpatient units could meet that goal? Could they do it any day of the week, at any time of the day or night?

ED systems had to be developed and implemented to ensure that appropriate candidates receive thrombolytic therapy in a timely manner. If those systems are not in place outside your hospital’s ED, then inpatient stroke cases are likely to miss the window of opportunity for thrombolytics. Ironically, they might have been better off going home and coming to the ED with any new symptoms. As a hospitalist, that is a sobering thought.

Hospitalist Ownership

It takes more than hospitalists being on-site to improve stroke outcomes. Processes need to be sharpened, roles defined, and outcomes monitored and acted upon to further sharpen the process. All of this plays to the strengths of hospitalists and should be undertaken with the vigor afforded to VTE prevention. This will take recognition that there’s a problem with the system, a dedication of resources, and a commitment to relentlessly work to improve and streamline the processes of stroke care.

In other words, it takes ownership. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group and hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado Denver. Ethan Cumbler, MD, contributed to this article. Dr. Cumbler is assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver and a member of the university’s Hospital Stroke Council.

This column represents the opinions of the author and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

References

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

A specialty without a disease: It was a major hangup for the field of hospital medicine in the early days. We’d hurdled many of the traditional barriers to specialty status—research fellowships, textbooks, an active society, a growing body of research, and thousands of practitioners focusing their practice on the hospital setting. However, despite several examples of site-defined specialties like emergency and critical-care medicine, cynics clung to the time-honored need for a specialty to own an organ, or at least a disease.

Early SHM efforts made a strong push to make VTE our disease—both its treatment and, more importantly, its prevention. It was a laudable effort, one that has saved many thousands of lives and limbs. It made sense for hospitalists to tackle VTE; it’s an incapacitating disease that affects many, is largely preventable, and had no strong inpatient advocate. While hematologists were the obvious “owner” of this disease, they were neither available nor able to redesign the inpatient systems of care necessary to thwart this illness. Hospitalists, invested in this issue by consequence of direct care of many at-risk patients and through commitment to improving hospital systems, came to own VTE prevention.

The Next Frontier: Stroke

It is time hospitalists apply this experience to the management of an even more incapacitating, largely preventable disease looking for an inpatient steward: stroke. A stroke occurs in the U.S. every 40 seconds, with disabling sequelae that often are avoidable with rapid detection and treatment. This is especially true when we are given the clarion call of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The problem is that most American hospitals are not kingpins of efficiency—the key ingredient of the processes necessary to improve stroke outcomes. Furthermore, while our neurologic colleagues are the obvious group to lead the deployment of stroke QI programs, there just aren’t enough of them to do so.

Hospitalists provide a significant amount of neurologic care. One study notes that TIA and stroke were among the most commonly cared-for diseases by hospitalists.1 This places us in a prime position to take the lead and own this disease in collaboration with our neurology colleagues. Just as with reliable VTE prevention, the key to effective stroke care requires effective systems engineering in conjunction with disease-specific expertise.

Rapid Care for Acute Medical Crisis

EDs are equipped with stroke pathways to efficiently evaluate, triage, scan, and intervene for patients who present with stroke symptoms. While most hospitals have a long way to go to perfect these systems, some hospitals—mostly in large, urban centers—have achieved the appropriate level of ED efficiency. These hospitals are recognized by The Joint Commission accreditation as stroke centers. As a result, patients who present to these hospitals with stroke symptoms often receive thrombolytics—a disease- and life-altering therapy—within the appropriate, but very limited, time window for benefit.

But what happens if that same patient develops those same signs and symptoms in the hospital? Will they get the same level of efficient evaluation, triage, scanning, and intervention that occurs in the ED? This is more than an academic question. Fifteen percent of all strokes are heralded by transient neurologic deficits, so many of the estimated 300,000 annual TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. What’s the reason for the admission? To facilitate the diagnostic workup, monitor for stroke symptoms and apply timely interventions should this occur.

But are we equipped to provide this kind of timely care in the hospital?

Case Study

Let’s take a 70-year-old diabetic male who presents with 45 minutes of aphasia and right-side arm weakness that resolve prior to presentation to the ED. If the patient is hypertensive on admission, the ABCD tool would suggest that he has a risk of stroke that approximates 20% in 90 days.2 Importantly, nearly half of that risk is in the first 48 hours. In other words, he has about a 10% risk of having a stroke in the next two days. Thus, we rightly admit him for monitoring in order to react quickly to any new signs and symptoms.

The problem is that most hospitals don’t have a system to efficiently manage patients who develop new stroke symptoms in the hospital. Does your hospital have an inpatient stroke pathway? That is, for a patient who has stroke onset while already in the hospital:

- Are the nurses aware of stroke signs and symptoms?

- Do nurses have a phone number to call to initiate an evaluation?

- Is there a team with stroke expertise immediately available to respond to those calls?

- Is there a priority path to get the patient promptly transported to the CT scanner for brain imaging with immediate radiology interpretation?

- How fast can thrombolytics be delivered, and is there an inpatient neurologist available 24/7 to assist?

The goal is 25 minutes from first recognition of symptoms to CT scan, and 60 minutes to complete evaluation and commencement of treatment. What percentage of your inpatient units could meet that goal? Could they do it any day of the week, at any time of the day or night?

ED systems had to be developed and implemented to ensure that appropriate candidates receive thrombolytic therapy in a timely manner. If those systems are not in place outside your hospital’s ED, then inpatient stroke cases are likely to miss the window of opportunity for thrombolytics. Ironically, they might have been better off going home and coming to the ED with any new symptoms. As a hospitalist, that is a sobering thought.

Hospitalist Ownership

It takes more than hospitalists being on-site to improve stroke outcomes. Processes need to be sharpened, roles defined, and outcomes monitored and acted upon to further sharpen the process. All of this plays to the strengths of hospitalists and should be undertaken with the vigor afforded to VTE prevention. This will take recognition that there’s a problem with the system, a dedication of resources, and a commitment to relentlessly work to improve and streamline the processes of stroke care.

In other words, it takes ownership. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group and hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado Denver. Ethan Cumbler, MD, contributed to this article. Dr. Cumbler is assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver and a member of the university’s Hospital Stroke Council.

This column represents the opinions of the author and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

References

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

A specialty without a disease: It was a major hangup for the field of hospital medicine in the early days. We’d hurdled many of the traditional barriers to specialty status—research fellowships, textbooks, an active society, a growing body of research, and thousands of practitioners focusing their practice on the hospital setting. However, despite several examples of site-defined specialties like emergency and critical-care medicine, cynics clung to the time-honored need for a specialty to own an organ, or at least a disease.

Early SHM efforts made a strong push to make VTE our disease—both its treatment and, more importantly, its prevention. It was a laudable effort, one that has saved many thousands of lives and limbs. It made sense for hospitalists to tackle VTE; it’s an incapacitating disease that affects many, is largely preventable, and had no strong inpatient advocate. While hematologists were the obvious “owner” of this disease, they were neither available nor able to redesign the inpatient systems of care necessary to thwart this illness. Hospitalists, invested in this issue by consequence of direct care of many at-risk patients and through commitment to improving hospital systems, came to own VTE prevention.

The Next Frontier: Stroke

It is time hospitalists apply this experience to the management of an even more incapacitating, largely preventable disease looking for an inpatient steward: stroke. A stroke occurs in the U.S. every 40 seconds, with disabling sequelae that often are avoidable with rapid detection and treatment. This is especially true when we are given the clarion call of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The problem is that most American hospitals are not kingpins of efficiency—the key ingredient of the processes necessary to improve stroke outcomes. Furthermore, while our neurologic colleagues are the obvious group to lead the deployment of stroke QI programs, there just aren’t enough of them to do so.

Hospitalists provide a significant amount of neurologic care. One study notes that TIA and stroke were among the most commonly cared-for diseases by hospitalists.1 This places us in a prime position to take the lead and own this disease in collaboration with our neurology colleagues. Just as with reliable VTE prevention, the key to effective stroke care requires effective systems engineering in conjunction with disease-specific expertise.

Rapid Care for Acute Medical Crisis

EDs are equipped with stroke pathways to efficiently evaluate, triage, scan, and intervene for patients who present with stroke symptoms. While most hospitals have a long way to go to perfect these systems, some hospitals—mostly in large, urban centers—have achieved the appropriate level of ED efficiency. These hospitals are recognized by The Joint Commission accreditation as stroke centers. As a result, patients who present to these hospitals with stroke symptoms often receive thrombolytics—a disease- and life-altering therapy—within the appropriate, but very limited, time window for benefit.

But what happens if that same patient develops those same signs and symptoms in the hospital? Will they get the same level of efficient evaluation, triage, scanning, and intervention that occurs in the ED? This is more than an academic question. Fifteen percent of all strokes are heralded by transient neurologic deficits, so many of the estimated 300,000 annual TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. What’s the reason for the admission? To facilitate the diagnostic workup, monitor for stroke symptoms and apply timely interventions should this occur.

But are we equipped to provide this kind of timely care in the hospital?

Case Study

Let’s take a 70-year-old diabetic male who presents with 45 minutes of aphasia and right-side arm weakness that resolve prior to presentation to the ED. If the patient is hypertensive on admission, the ABCD tool would suggest that he has a risk of stroke that approximates 20% in 90 days.2 Importantly, nearly half of that risk is in the first 48 hours. In other words, he has about a 10% risk of having a stroke in the next two days. Thus, we rightly admit him for monitoring in order to react quickly to any new signs and symptoms.

The problem is that most hospitals don’t have a system to efficiently manage patients who develop new stroke symptoms in the hospital. Does your hospital have an inpatient stroke pathway? That is, for a patient who has stroke onset while already in the hospital:

- Are the nurses aware of stroke signs and symptoms?

- Do nurses have a phone number to call to initiate an evaluation?

- Is there a team with stroke expertise immediately available to respond to those calls?

- Is there a priority path to get the patient promptly transported to the CT scanner for brain imaging with immediate radiology interpretation?

- How fast can thrombolytics be delivered, and is there an inpatient neurologist available 24/7 to assist?

The goal is 25 minutes from first recognition of symptoms to CT scan, and 60 minutes to complete evaluation and commencement of treatment. What percentage of your inpatient units could meet that goal? Could they do it any day of the week, at any time of the day or night?

ED systems had to be developed and implemented to ensure that appropriate candidates receive thrombolytic therapy in a timely manner. If those systems are not in place outside your hospital’s ED, then inpatient stroke cases are likely to miss the window of opportunity for thrombolytics. Ironically, they might have been better off going home and coming to the ED with any new symptoms. As a hospitalist, that is a sobering thought.

Hospitalist Ownership

It takes more than hospitalists being on-site to improve stroke outcomes. Processes need to be sharpened, roles defined, and outcomes monitored and acted upon to further sharpen the process. All of this plays to the strengths of hospitalists and should be undertaken with the vigor afforded to VTE prevention. This will take recognition that there’s a problem with the system, a dedication of resources, and a commitment to relentlessly work to improve and streamline the processes of stroke care.

In other words, it takes ownership. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group and hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado Denver. Ethan Cumbler, MD, contributed to this article. Dr. Cumbler is assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver and a member of the university’s Hospital Stroke Council.

This column represents the opinions of the author and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

References

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.