User login

Introduction

Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been recognized with increased frequency as a cause of nosocomial illness. The frequency and incidence of CDAD varies widely, and is influenced by multiple factors including nosocomial outbreaks, patterns of antimicrobial use, and individual susceptibility. There are no reports of prospective studies by hospitals tracking positive toxin A or A/B and the outcomes of CDAD and its complications.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has analyzed secular trends in the incidence of CDAD, and it reported a steady increase from 1987 to 2001 (1). In this report, 30% of 440 infectious disease physicians who participated in a Web-based poll reported that they are seeing higher rates of CDAD, more severe CDAD, and more relapsing CDAD than in the past. There is an overall impression that there has been an increase in the proportion of cases with severe and fatal complications, and an increase in the relapse rate among affected patients.

In addition to morbidity and mortality, the economic burden of C. difficile infection in terms of delayed discharge and other hospital costs is considerable.

Epidemiology

The frequency and incidence of CDAD varies between hospitals and within a given institution over time. The risk for disease increases in patients with antibiotic exposure, gastrointestinal surgery, increasing length of stay in healthcare settings, serious underlying illness, immuno-compromising conditions, and advanced age.

C. difficile is shed in feces. Any surface, device, or material (e.g., commode, bathing tub, and electronic rectal thermometer) that becomes contaminated with feces may serve as a reservoir for C. difficile spores. Spores are transferred to patients mainly via the hands of healthcare personnel who have touched a contaminated surface or item (2-6).

The Organism and Pathophysiology of C. difficile Diarrhea

C. difficile is a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacillus that is responsible for the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis. C. difficile was first described in 1935 as a component of the fecal flora of healthy newborns and was initially not thought to be pathogenic (7). The bacillus was named difficile because it grows slowly and is difficult to culture. C. difficile is presently responsible for nearly all causes of pseudomembranous colitis and as many as 20% of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea without colitis. Although found in the stool of only 5% of the general population, as many as 21% of adults become colonized with this organism while hospitalized (2,6).

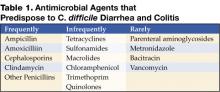

An alteration of the normal colonic microflora, usually caused by antibiotic therapy, is the main factor that predisposes to infection with C. difficile. Almost all antibiotics have been associated with C. difficile diarrhea and colitis. The antibiotics most frequently associated include clindamycin, cephalosporins, ampicillin, and amoxicillin (Table 1) (8).

In addition to antibiotic therapy, older age and severity of underlying disease are important risk factors for C. difficile infection. Other risk factors include the presence of a nasogastric tube, gastrointestinal procedures, acid antisecretory medications, intensive care unit stay, and duration of hospitalization (9).

C. difficile diarrhea is caused primarily by the elaboration of toxins A and B produced by bacterial multiplication within the intestinal lumen. These toxins bind to the colonic mucosa and exert their deleterious effects upon it. The organism rarely damages the colon by direct invasion, and diarrhea is caused by the effects of toxins produced within the intestinal lumen that adhere to the mucosal surface. Most toxigenic isolates produce both toxins, and about 5–25% of isolates produce neither toxin A nor B, and do not cause colitis or diarrhea (3-5).

Clinical Manifestations

Infection with C. difficile may produce a wide range of clinical manifestations, including asymptomatic carriage, mild-to-moderate diarrhea, and fulminant disease with pseudomembranous colitis (10). In patients who develop CDAD, symptoms usually begin soon after colonization. Colonization may occur during antibiotic treatment or up to several weeks after a course of antibiotics. CDAD typically is associated with the passage of frequent, loose bowel movements consistent with proctocolitis. Mucus or occult blood may be present, but visible blood is rare.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CDAD is based on a history of recent or current antibiotic therapy, development of diarrhea or other evidence of acute colitis, and demonstration of infection by toxigenic C. difficile, usually by detection of toxin A or toxin B in stool sample.

Practical Guidelines for Diagnosis of C. difficile Diarrheal Syndromes

- The diagnosis should be suspected in anyone with diarrhea who has received antibiotics within the previous 2 months and/or whose diarrhea begins 72 hours or more after hospitalization.

- When the diagnosis is suspected, a single stool specimen should be sent to the laboratory for testing for the presence of C. difficile and/or its toxins.

- When diarrhea persists despite a negative stool toxin result, one or two additional samples may be sent for testing with the same or different tests (4). Endoscopy is reserved for special situations, such as when a rapid diagnosis is needed and test results are delayed or the test is not highly sensitive, when the patient has ileus and stool is not available, or when other colonic diseases are also a consideration.

There is as yet no simple, inexpensive, rapid, sensitive and specific test for diagnosing C. difficile diarrhea and colitis, nor are all the available tests suitable for adoption by every laboratory (Table 2) (11).

Endoscopic Diagnosis of C. difficile Diarrhea and Colitis

Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are not indicated for most patients with CDAD (10,12). Endoscopy is helpful, however, in special situations, such as when the diagnosis is in doubt or the clinical situation demands rapid diagnosis. The results of endoscopic examination may be normal in patients with mild diarrhea or may show nonspecific colitis in moderate cases. The finding of colonic pseudomembranes in a patient with antibiotic-associated diarrhea is virtually pathognomonic for C. difficile colitis. A few patients without any diagnostic features in the rectosigmoid have pseudomembranes in the more proximal areas of the colon (13). Other endoscopic findings include erythema, edema, friability, and nonspecific colitis with small ulcerations or erosions.

Treatment

The first step in the management of C. difficile diarrhea and colitis is to discontinue the precipitating antibiotics if possible (10,12). Diarrhea resolves in approximately 15–25% of patients without specific anti–C. difficile therapy (14,15). Conservative management alone may not be indicated, however, in patients who are systemically ill or who have multiple medical problems, since it is difficult to predict which patients will improve spontaneously. If it is not possible to discontinue the precipitating antibiotic because of other active infections, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be altered if possible to make use of agents less likely to cause CDAD (e.g., aminoglycosides, trimethoprim, rifampin, or a quinolone).

Antiperistaltic agents, such as diphenoxylate plus atropine (Lomotil), or loperamide (Imodium), and narcotic analgesics should be avoided because they may delay clearance of toxins from the colon and thereby exacerbate toxin-induced colonic injury or precipitate ileus and toxic dilatation (12,16). Specific therapy to eradicate C. difficile should be used in patients with initially severe symptoms and in patients whose symptoms persist despite discontinuation of antibiotic treatment. Although the diagnosis of C. difficile colitis should ideally be established before antimicrobial therapy is implemented, current ACG guidelines recommend that empiric therapy should be initiated in highly suggestive cases of severely ill patients (Table 3 on page 54) (12).

Currently, oral vancomycin or metronidazole, used for 7 to 10 days, are considered first-line therapy by most authors and current guidelines. Metronidazole at a dose of 250 mg 4 times daily is recommended by most authors and ACG guidelines as the drug of choice for the initial treatment of C. difficile colitis (12). These recommendations are largely based on efficacy, lower costs, and concerns about the development of vancomycin-resistant strains. Major disadvantages of metronidazole include a less desirable drug profile and contraindications in children and pregnant women.

Vancomycin, on the other hand, at a dose of 125 mg 4 times daily, is safe and well tolerated and achieves stool levels 20 times the required minimal inhibitory concentration for the treatment of C. difficile. Drawbacks to the use of vancomycin are cost and potential development of vancomycin-resistant strains. The current ACG guidelines consider vancomycin the drug of choice in severely ill patients and in cases in which the use of metronidazole is precluded.

Controlled clinical trials are lacking for patients with fulminant colitis who may not tolerate oral therapy. Administration of metronidazole intravenously or administration of vancomycin by nasogastric tube or rectal enema has been described in small case series (17-20). Intravenous administration of vancomycin is not recommended, because the drug is not excreted in the colon (17).

Management of Recurrent C. difficile Diarrhea

Despite successful initial treatment of CDAD, 15–20% of patients have recurrence of diarrhea in association with a positive stool test for C. difficile toxin. Symptomatic recurrence is rarely due to treatment failure or antimicrobial resistance to metronidazole or vancomycin. Approaches to management include conservative therapy (however, many patients are elderly and infirm and unable to tolerate diarrhea), therapy with specific anti–C. difficile antibiotics, the use of anion-binding resins, therapy with microorganisms (probiotics), and immunoglobulin therapy.

The most common therapy for recurrent C. difficile diarrhea is a second course of the same antibiotic used to treat the initial episode (12). In a large observational study in the United States, 92% of patients with recurrent CDAD responded successfully to a single repeated course of therapy, usually with metronidazole or vancomycin (14). There is evidence to suggest that patients with a history of recurrence have a high risk of further episodes of CDAD after antibiotic therapy is discontinued. There are no data to suggest that sequential episodes become progressively more severe or complicated (21). A variety of treatment schedules have been suggested for patients with multiple recurrences of C. difficile diarrhea. One approach is to give a prolonged course of vancomycin (or metronidazole) using a decreasing dosage schedule followed by pulse therapy (Table 4).

Cholestyramine, an anionexchange resin administered at a dose of 4 grams 3 or 4 times daily for 1 to 2 weeks, binds C. difficile toxins and may be used in conjunction with antibiotics to treat repeated relapses. Because cholestyramine may bind vancomycin as well as toxins, it should be taken at least 2 to 3 hours apart from the vancomycin.

Severe C. difficile Colitis

The incidence of fulminant C. difficile colitis has been reported to be 1.6–3.2% (22). Although recent precise figures from other centers are lacking, it is being recognized as an increasing cause of complications and death. The clinical syndrome of fulminant C. difficile colitis can be recognized with a proper knowledge of the spectrum of disease presentation.

A. Diarrhea: Although diarrhea is the hallmark of C. difficile colitis, it is not invariably present, and its absence may lead to diagnostic confusion. When diarrhea is absent, this appears to be secondary to severe colonic dysmotility. Even when present, diarrhea may be perceived to be a minor component of a nonspecific septic picture.

B. Severe Disease: Fulminant colitis is an unusual form of C. difficile infection, occurring in only 3% of patients but accounting for virtually all serious complications. Patients with more severe forms of the disease may present with or without diarrhea. When patients develop colitis localized to the cecum and right side of the colon, diarrhea may be minimal or absent. In the absence of diarrhea, the only clues to diagnosis may be systemic signs of toxicity (fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and/or volume depletion).

An elevated white blood cell count may be an important clue to impending fulminant C. difficile colitis. The rapid elevation of the peripheral white cell count (commonly as high as 30,000 to 50,000) with a significant excess of bands and sometimes more immature forms often precedes hemodynamic instability and the development of organ dysfunction. Even in patients who are mildly symptomatic for an extended period, sudden and unexpected progression to shock may occur. It is difficult to predict those patients who may not respond to medical treatment. Hence, early warning signs such as a leukemoid reaction may be invaluable.

Hypotension is a late finding and can be resistant to vasopressor support. Abdominal signs range from distention to generalized tenderness with guarding. Colonic perforation is usually accompanied by abdominal rigidity, involuntary guarding, rebound tenderness, and absent bowel sounds. Free air may be revealed on abdominal radiographs. Any suspicion of perforation in this setting should prompt immediate surgical consultation. Death generally occurs before free air and perforation can occur. In one study, contrary to most other literature, perforation was found to be rare (22).

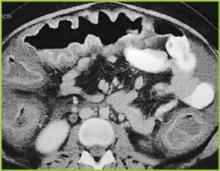

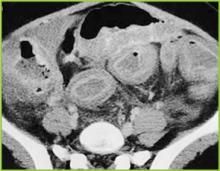

Abdominal radiography may reveal a dilated colon (>7 cm in its greatest diameter), consistent with toxic megacolon. Patients with megacolon may have an associated small bowel ileus with dilated small intestine on plain abdominal radiographs, with air-fluid levels mimicking small intestinal obstruction or ischemia. CT without contrast and endoscopy can quickly diagnose or at least strongly suggest fulminant C.difficile colitis. CT scan findings include evidence of ascites, colonic wall thickening and/or dilatation. These findings may prove helpful in categorizing the severity of the colitis.

More aggressive intervention in medically unresponsive patients, including rapid identification of patients failing to respond to medical therapy, is crucial to a positive outcome, and early surgical intervention should be done in this group (Figures 1-3).

It is important that everyone involved with patient care in hospitals, nursing homes, and skilled nursing facilities be educated about the organism and its epidemiology, rational approaches to the treatment and care of patients with C. difficile diarrhea, the importance of hand washing between contact with patients, the use of gloves when caring for a patient with C. difficile diarrhea, and the avoidance of the unnecessary use of antimicrobials.

Conclusion

Recent years have raised concerns over rising incidence and serious complication rates of CDAD in North American hospitals (22,23). The Canadian Medical Association journal published a report in 2004 detailing an outbreak of CDAD involving several hospitals in Montreal. The introduction of new hypervirulent and highly transmissible strains of C. difficile has been postulated as the possible cause for the outbreak (24). A deteriorating infrastructure, inadequate infection control practices, the increasing number of debilitated patients, an aging population, and hypervirulent strains were all felt to be likely contributors to recent outbreaks in Canada (25).

Two epidemiological investigations in the United States and Canada (24,26) independently examined samples of C. difficile and found that a mutated version of the “wild” strain was responsible for outbreaks in Quebec and increased rates of CDAD in hospitals in the United States recently (22,23). Clinical epidemiologists at the CDC investigated C. difficile isolates from hospitals in the United States with recent (i.e., 2001–2004) CDAD outbreaks (22,23). The report indicates the emergence of a new epidemic strain, “BI” (distinct from the “J” strain of 1989–1992), which may be responsible for the recent increase in rates and apparent severity of CDAD (26).

CDAD and colitis in most cases can be treated by the administration of metronidazole or vancomycin. In some patients severe life-threatening toxicity develops despite appropriate and timely medical treatment, and surgical intervention is necessary. Systemic symptoms of infection with C. difficile are reported not to derive from bacteremia, colonic perforation or ischemia, but from toxin-induced inflammatory mediators released from the colon (27-29). Early surgical intervention should be employed in refractory cases of severe disease. Surgical intervention is far from ideal, however, and carries a very high rate of complications and significant risk of mortality (22). The future clinical approach to the treatment of nosocomial C. difficile colitis may eventually involve specific antitoxin hyperimmunoglobulins and inhibitors of the inflammatory cascade (28,30,31).

References

- Archibald LK, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Secular trend in hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile disease in the United States; 1987-2001. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1585-9.

- Fekety R. Antibiotic-associated colitis. In: Mandell G, Bennet JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingston; 1996:978-806.

- Mitty RD, LaMont T. Clostridium difficile diarrhea: Pathogenesis, epidemiology, and treatment. Gastroenterologist. 1994;2:61-9.

- Bartlett JG. Clostridium difficile: History of its role as an enteric pathogen and the current state of knowledge about the organism. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl 4):265-72.

- Johnson S, Gerding D. Clostridium difficile. In: Mayhall CG, ed. Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:99-408.

- Mcfarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204-10.

- Hall IC, O Toole E. Intestinal Flora in new-born infants: With a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficile. Am J Dis Child. 1935;49:390-402.

- Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. In: Wolfe MM, ed. Gastrointestinal Pharmacotherapy. Philadelphia, Pa.: WB Saunders; 1993:199-212.

- Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 1998;40:1-15.

- Kelly CP, Pothoulakas C, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile colitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:257-62.

- Linevsky JK, Kelly CP. Clostridium difficile colitis. In: Lamont JT, ed. Gastrointestinal Infections: Diagnosis and Management. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997:293-325.

- Fekety R. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea and colitis. American College of Gastroenetrology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:739-50.

- Tedesco FJ, Corless JK, Brownstein RE. Rectal sparing in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis: A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1259-60.

- Olson MM, Shanholtzer CJ, Lee JT Jr, Gerding DN. Ten years of prospective Clostridium difficile-associated disease surveillance and treatment at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, 1982-1991. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15: 371-81.

- Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhoea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-6.

- Walley T, Milson D. Loperamide-related toxic megacolon in Clostridium difficile colitis. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:582.

- Malnick SD, Zimhony O. Treatment of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1767-75.

- Sehgal M, Kyne L. Clostridium difficile disease. Curr Treatment Options Infect Dis. 2002;4:201-10.

- Apisarnthanarak A, Razavi B, Mundy LM. Adjunctive intracolonic vancomycin for severe Clostridium difficile colitis: case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:690-6.

- Friendenberg F, Fernandez A, Kaul V, Niami P, Levine GM. Intravenous metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1176-80.

- Fekety R, McFarland LV, Surawicz CMGreenberg, RN, Elmer GW, Mulligan ME. Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324-33.

- Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363-72.

- Morris AM, Jobe BA, Sontey, M, Sheppard BC, Deveney CW, Deveney KE. Clostridium difficile colitis: an increasingly aggressive iatrogenic disease? Arch Surg. 2002;137:1096-100.

- Eggerston L, Sibbald B. Hospitals battling outbreaks of C. difficile. CMAJ. 2004;171:19-21.

- Valiquette L, Low DE, Pepin J, McGeer A. Clostridium difficile infection in hospitals: a brewing storm. CMAJ. 2004;171:27-9.

- McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, et al. Emergence of an epidemic strain of Clostridium difficile in the United States, 2001-4: Potential role for virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance traits. Infectious Diseases Society of America 42th Annual Meeting. Boston, MA, September 30 – October 3, 2004. Abstract # LB-2.

- Flegel W, Muller F, Daubener W, Fischer HG, Hadding U, Northoff H. Cytokine response by human monocytes to Clostridium difficile toxin A and toxin B. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3659-66.

- Castagliuolo I, Keates A, Qiu B, et al. Increased substance P responses in dorsal root ganglia, intestinal macrophages during Clostridium difficile toxin A enteritis in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4788-93.

- Castagliuolo I, Keates A, Wang C, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin A stimulates macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 production in rat intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:6039-45.

- Kelly C, Chetham S, Keates S, et al. Survival of anti-Clostridium difficile bovine immunoglobulin concentrate in the human gastrointestinal tract. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:236-41.

- Salcedo J, Keates S, Pothoulakis C, et. al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Gut. 1997;41:366-70.

General References

- Shea Position Paper Gerding DN,Johnson S, Peterson LR, Mulligan ME Silva J. SHEA Position Paper:Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis; Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1995, 16:459-77

- Kyne L, Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2001; 30:753-77.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been recognized with increased frequency as a cause of nosocomial illness. The frequency and incidence of CDAD varies widely, and is influenced by multiple factors including nosocomial outbreaks, patterns of antimicrobial use, and individual susceptibility. There are no reports of prospective studies by hospitals tracking positive toxin A or A/B and the outcomes of CDAD and its complications.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has analyzed secular trends in the incidence of CDAD, and it reported a steady increase from 1987 to 2001 (1). In this report, 30% of 440 infectious disease physicians who participated in a Web-based poll reported that they are seeing higher rates of CDAD, more severe CDAD, and more relapsing CDAD than in the past. There is an overall impression that there has been an increase in the proportion of cases with severe and fatal complications, and an increase in the relapse rate among affected patients.

In addition to morbidity and mortality, the economic burden of C. difficile infection in terms of delayed discharge and other hospital costs is considerable.

Epidemiology

The frequency and incidence of CDAD varies between hospitals and within a given institution over time. The risk for disease increases in patients with antibiotic exposure, gastrointestinal surgery, increasing length of stay in healthcare settings, serious underlying illness, immuno-compromising conditions, and advanced age.

C. difficile is shed in feces. Any surface, device, or material (e.g., commode, bathing tub, and electronic rectal thermometer) that becomes contaminated with feces may serve as a reservoir for C. difficile spores. Spores are transferred to patients mainly via the hands of healthcare personnel who have touched a contaminated surface or item (2-6).

The Organism and Pathophysiology of C. difficile Diarrhea

C. difficile is a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacillus that is responsible for the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis. C. difficile was first described in 1935 as a component of the fecal flora of healthy newborns and was initially not thought to be pathogenic (7). The bacillus was named difficile because it grows slowly and is difficult to culture. C. difficile is presently responsible for nearly all causes of pseudomembranous colitis and as many as 20% of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea without colitis. Although found in the stool of only 5% of the general population, as many as 21% of adults become colonized with this organism while hospitalized (2,6).

An alteration of the normal colonic microflora, usually caused by antibiotic therapy, is the main factor that predisposes to infection with C. difficile. Almost all antibiotics have been associated with C. difficile diarrhea and colitis. The antibiotics most frequently associated include clindamycin, cephalosporins, ampicillin, and amoxicillin (Table 1) (8).

In addition to antibiotic therapy, older age and severity of underlying disease are important risk factors for C. difficile infection. Other risk factors include the presence of a nasogastric tube, gastrointestinal procedures, acid antisecretory medications, intensive care unit stay, and duration of hospitalization (9).

C. difficile diarrhea is caused primarily by the elaboration of toxins A and B produced by bacterial multiplication within the intestinal lumen. These toxins bind to the colonic mucosa and exert their deleterious effects upon it. The organism rarely damages the colon by direct invasion, and diarrhea is caused by the effects of toxins produced within the intestinal lumen that adhere to the mucosal surface. Most toxigenic isolates produce both toxins, and about 5–25% of isolates produce neither toxin A nor B, and do not cause colitis or diarrhea (3-5).

Clinical Manifestations

Infection with C. difficile may produce a wide range of clinical manifestations, including asymptomatic carriage, mild-to-moderate diarrhea, and fulminant disease with pseudomembranous colitis (10). In patients who develop CDAD, symptoms usually begin soon after colonization. Colonization may occur during antibiotic treatment or up to several weeks after a course of antibiotics. CDAD typically is associated with the passage of frequent, loose bowel movements consistent with proctocolitis. Mucus or occult blood may be present, but visible blood is rare.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CDAD is based on a history of recent or current antibiotic therapy, development of diarrhea or other evidence of acute colitis, and demonstration of infection by toxigenic C. difficile, usually by detection of toxin A or toxin B in stool sample.

Practical Guidelines for Diagnosis of C. difficile Diarrheal Syndromes

- The diagnosis should be suspected in anyone with diarrhea who has received antibiotics within the previous 2 months and/or whose diarrhea begins 72 hours or more after hospitalization.

- When the diagnosis is suspected, a single stool specimen should be sent to the laboratory for testing for the presence of C. difficile and/or its toxins.

- When diarrhea persists despite a negative stool toxin result, one or two additional samples may be sent for testing with the same or different tests (4). Endoscopy is reserved for special situations, such as when a rapid diagnosis is needed and test results are delayed or the test is not highly sensitive, when the patient has ileus and stool is not available, or when other colonic diseases are also a consideration.

There is as yet no simple, inexpensive, rapid, sensitive and specific test for diagnosing C. difficile diarrhea and colitis, nor are all the available tests suitable for adoption by every laboratory (Table 2) (11).

Endoscopic Diagnosis of C. difficile Diarrhea and Colitis

Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are not indicated for most patients with CDAD (10,12). Endoscopy is helpful, however, in special situations, such as when the diagnosis is in doubt or the clinical situation demands rapid diagnosis. The results of endoscopic examination may be normal in patients with mild diarrhea or may show nonspecific colitis in moderate cases. The finding of colonic pseudomembranes in a patient with antibiotic-associated diarrhea is virtually pathognomonic for C. difficile colitis. A few patients without any diagnostic features in the rectosigmoid have pseudomembranes in the more proximal areas of the colon (13). Other endoscopic findings include erythema, edema, friability, and nonspecific colitis with small ulcerations or erosions.

Treatment

The first step in the management of C. difficile diarrhea and colitis is to discontinue the precipitating antibiotics if possible (10,12). Diarrhea resolves in approximately 15–25% of patients without specific anti–C. difficile therapy (14,15). Conservative management alone may not be indicated, however, in patients who are systemically ill or who have multiple medical problems, since it is difficult to predict which patients will improve spontaneously. If it is not possible to discontinue the precipitating antibiotic because of other active infections, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be altered if possible to make use of agents less likely to cause CDAD (e.g., aminoglycosides, trimethoprim, rifampin, or a quinolone).

Antiperistaltic agents, such as diphenoxylate plus atropine (Lomotil), or loperamide (Imodium), and narcotic analgesics should be avoided because they may delay clearance of toxins from the colon and thereby exacerbate toxin-induced colonic injury or precipitate ileus and toxic dilatation (12,16). Specific therapy to eradicate C. difficile should be used in patients with initially severe symptoms and in patients whose symptoms persist despite discontinuation of antibiotic treatment. Although the diagnosis of C. difficile colitis should ideally be established before antimicrobial therapy is implemented, current ACG guidelines recommend that empiric therapy should be initiated in highly suggestive cases of severely ill patients (Table 3 on page 54) (12).

Currently, oral vancomycin or metronidazole, used for 7 to 10 days, are considered first-line therapy by most authors and current guidelines. Metronidazole at a dose of 250 mg 4 times daily is recommended by most authors and ACG guidelines as the drug of choice for the initial treatment of C. difficile colitis (12). These recommendations are largely based on efficacy, lower costs, and concerns about the development of vancomycin-resistant strains. Major disadvantages of metronidazole include a less desirable drug profile and contraindications in children and pregnant women.

Vancomycin, on the other hand, at a dose of 125 mg 4 times daily, is safe and well tolerated and achieves stool levels 20 times the required minimal inhibitory concentration for the treatment of C. difficile. Drawbacks to the use of vancomycin are cost and potential development of vancomycin-resistant strains. The current ACG guidelines consider vancomycin the drug of choice in severely ill patients and in cases in which the use of metronidazole is precluded.

Controlled clinical trials are lacking for patients with fulminant colitis who may not tolerate oral therapy. Administration of metronidazole intravenously or administration of vancomycin by nasogastric tube or rectal enema has been described in small case series (17-20). Intravenous administration of vancomycin is not recommended, because the drug is not excreted in the colon (17).

Management of Recurrent C. difficile Diarrhea

Despite successful initial treatment of CDAD, 15–20% of patients have recurrence of diarrhea in association with a positive stool test for C. difficile toxin. Symptomatic recurrence is rarely due to treatment failure or antimicrobial resistance to metronidazole or vancomycin. Approaches to management include conservative therapy (however, many patients are elderly and infirm and unable to tolerate diarrhea), therapy with specific anti–C. difficile antibiotics, the use of anion-binding resins, therapy with microorganisms (probiotics), and immunoglobulin therapy.

The most common therapy for recurrent C. difficile diarrhea is a second course of the same antibiotic used to treat the initial episode (12). In a large observational study in the United States, 92% of patients with recurrent CDAD responded successfully to a single repeated course of therapy, usually with metronidazole or vancomycin (14). There is evidence to suggest that patients with a history of recurrence have a high risk of further episodes of CDAD after antibiotic therapy is discontinued. There are no data to suggest that sequential episodes become progressively more severe or complicated (21). A variety of treatment schedules have been suggested for patients with multiple recurrences of C. difficile diarrhea. One approach is to give a prolonged course of vancomycin (or metronidazole) using a decreasing dosage schedule followed by pulse therapy (Table 4).

Cholestyramine, an anionexchange resin administered at a dose of 4 grams 3 or 4 times daily for 1 to 2 weeks, binds C. difficile toxins and may be used in conjunction with antibiotics to treat repeated relapses. Because cholestyramine may bind vancomycin as well as toxins, it should be taken at least 2 to 3 hours apart from the vancomycin.

Severe C. difficile Colitis

The incidence of fulminant C. difficile colitis has been reported to be 1.6–3.2% (22). Although recent precise figures from other centers are lacking, it is being recognized as an increasing cause of complications and death. The clinical syndrome of fulminant C. difficile colitis can be recognized with a proper knowledge of the spectrum of disease presentation.

A. Diarrhea: Although diarrhea is the hallmark of C. difficile colitis, it is not invariably present, and its absence may lead to diagnostic confusion. When diarrhea is absent, this appears to be secondary to severe colonic dysmotility. Even when present, diarrhea may be perceived to be a minor component of a nonspecific septic picture.

B. Severe Disease: Fulminant colitis is an unusual form of C. difficile infection, occurring in only 3% of patients but accounting for virtually all serious complications. Patients with more severe forms of the disease may present with or without diarrhea. When patients develop colitis localized to the cecum and right side of the colon, diarrhea may be minimal or absent. In the absence of diarrhea, the only clues to diagnosis may be systemic signs of toxicity (fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and/or volume depletion).

An elevated white blood cell count may be an important clue to impending fulminant C. difficile colitis. The rapid elevation of the peripheral white cell count (commonly as high as 30,000 to 50,000) with a significant excess of bands and sometimes more immature forms often precedes hemodynamic instability and the development of organ dysfunction. Even in patients who are mildly symptomatic for an extended period, sudden and unexpected progression to shock may occur. It is difficult to predict those patients who may not respond to medical treatment. Hence, early warning signs such as a leukemoid reaction may be invaluable.

Hypotension is a late finding and can be resistant to vasopressor support. Abdominal signs range from distention to generalized tenderness with guarding. Colonic perforation is usually accompanied by abdominal rigidity, involuntary guarding, rebound tenderness, and absent bowel sounds. Free air may be revealed on abdominal radiographs. Any suspicion of perforation in this setting should prompt immediate surgical consultation. Death generally occurs before free air and perforation can occur. In one study, contrary to most other literature, perforation was found to be rare (22).

Abdominal radiography may reveal a dilated colon (>7 cm in its greatest diameter), consistent with toxic megacolon. Patients with megacolon may have an associated small bowel ileus with dilated small intestine on plain abdominal radiographs, with air-fluid levels mimicking small intestinal obstruction or ischemia. CT without contrast and endoscopy can quickly diagnose or at least strongly suggest fulminant C.difficile colitis. CT scan findings include evidence of ascites, colonic wall thickening and/or dilatation. These findings may prove helpful in categorizing the severity of the colitis.

More aggressive intervention in medically unresponsive patients, including rapid identification of patients failing to respond to medical therapy, is crucial to a positive outcome, and early surgical intervention should be done in this group (Figures 1-3).

It is important that everyone involved with patient care in hospitals, nursing homes, and skilled nursing facilities be educated about the organism and its epidemiology, rational approaches to the treatment and care of patients with C. difficile diarrhea, the importance of hand washing between contact with patients, the use of gloves when caring for a patient with C. difficile diarrhea, and the avoidance of the unnecessary use of antimicrobials.

Conclusion

Recent years have raised concerns over rising incidence and serious complication rates of CDAD in North American hospitals (22,23). The Canadian Medical Association journal published a report in 2004 detailing an outbreak of CDAD involving several hospitals in Montreal. The introduction of new hypervirulent and highly transmissible strains of C. difficile has been postulated as the possible cause for the outbreak (24). A deteriorating infrastructure, inadequate infection control practices, the increasing number of debilitated patients, an aging population, and hypervirulent strains were all felt to be likely contributors to recent outbreaks in Canada (25).

Two epidemiological investigations in the United States and Canada (24,26) independently examined samples of C. difficile and found that a mutated version of the “wild” strain was responsible for outbreaks in Quebec and increased rates of CDAD in hospitals in the United States recently (22,23). Clinical epidemiologists at the CDC investigated C. difficile isolates from hospitals in the United States with recent (i.e., 2001–2004) CDAD outbreaks (22,23). The report indicates the emergence of a new epidemic strain, “BI” (distinct from the “J” strain of 1989–1992), which may be responsible for the recent increase in rates and apparent severity of CDAD (26).

CDAD and colitis in most cases can be treated by the administration of metronidazole or vancomycin. In some patients severe life-threatening toxicity develops despite appropriate and timely medical treatment, and surgical intervention is necessary. Systemic symptoms of infection with C. difficile are reported not to derive from bacteremia, colonic perforation or ischemia, but from toxin-induced inflammatory mediators released from the colon (27-29). Early surgical intervention should be employed in refractory cases of severe disease. Surgical intervention is far from ideal, however, and carries a very high rate of complications and significant risk of mortality (22). The future clinical approach to the treatment of nosocomial C. difficile colitis may eventually involve specific antitoxin hyperimmunoglobulins and inhibitors of the inflammatory cascade (28,30,31).

References

- Archibald LK, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Secular trend in hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile disease in the United States; 1987-2001. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1585-9.

- Fekety R. Antibiotic-associated colitis. In: Mandell G, Bennet JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingston; 1996:978-806.

- Mitty RD, LaMont T. Clostridium difficile diarrhea: Pathogenesis, epidemiology, and treatment. Gastroenterologist. 1994;2:61-9.

- Bartlett JG. Clostridium difficile: History of its role as an enteric pathogen and the current state of knowledge about the organism. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl 4):265-72.

- Johnson S, Gerding D. Clostridium difficile. In: Mayhall CG, ed. Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:99-408.

- Mcfarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204-10.

- Hall IC, O Toole E. Intestinal Flora in new-born infants: With a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficile. Am J Dis Child. 1935;49:390-402.

- Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. In: Wolfe MM, ed. Gastrointestinal Pharmacotherapy. Philadelphia, Pa.: WB Saunders; 1993:199-212.

- Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 1998;40:1-15.

- Kelly CP, Pothoulakas C, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile colitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:257-62.

- Linevsky JK, Kelly CP. Clostridium difficile colitis. In: Lamont JT, ed. Gastrointestinal Infections: Diagnosis and Management. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997:293-325.

- Fekety R. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea and colitis. American College of Gastroenetrology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:739-50.

- Tedesco FJ, Corless JK, Brownstein RE. Rectal sparing in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis: A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1259-60.

- Olson MM, Shanholtzer CJ, Lee JT Jr, Gerding DN. Ten years of prospective Clostridium difficile-associated disease surveillance and treatment at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, 1982-1991. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15: 371-81.

- Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhoea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-6.

- Walley T, Milson D. Loperamide-related toxic megacolon in Clostridium difficile colitis. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:582.

- Malnick SD, Zimhony O. Treatment of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1767-75.

- Sehgal M, Kyne L. Clostridium difficile disease. Curr Treatment Options Infect Dis. 2002;4:201-10.

- Apisarnthanarak A, Razavi B, Mundy LM. Adjunctive intracolonic vancomycin for severe Clostridium difficile colitis: case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:690-6.

- Friendenberg F, Fernandez A, Kaul V, Niami P, Levine GM. Intravenous metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1176-80.

- Fekety R, McFarland LV, Surawicz CMGreenberg, RN, Elmer GW, Mulligan ME. Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324-33.

- Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363-72.

- Morris AM, Jobe BA, Sontey, M, Sheppard BC, Deveney CW, Deveney KE. Clostridium difficile colitis: an increasingly aggressive iatrogenic disease? Arch Surg. 2002;137:1096-100.

- Eggerston L, Sibbald B. Hospitals battling outbreaks of C. difficile. CMAJ. 2004;171:19-21.

- Valiquette L, Low DE, Pepin J, McGeer A. Clostridium difficile infection in hospitals: a brewing storm. CMAJ. 2004;171:27-9.

- McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, et al. Emergence of an epidemic strain of Clostridium difficile in the United States, 2001-4: Potential role for virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance traits. Infectious Diseases Society of America 42th Annual Meeting. Boston, MA, September 30 – October 3, 2004. Abstract # LB-2.

- Flegel W, Muller F, Daubener W, Fischer HG, Hadding U, Northoff H. Cytokine response by human monocytes to Clostridium difficile toxin A and toxin B. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3659-66.

- Castagliuolo I, Keates A, Qiu B, et al. Increased substance P responses in dorsal root ganglia, intestinal macrophages during Clostridium difficile toxin A enteritis in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4788-93.

- Castagliuolo I, Keates A, Wang C, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin A stimulates macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 production in rat intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:6039-45.

- Kelly C, Chetham S, Keates S, et al. Survival of anti-Clostridium difficile bovine immunoglobulin concentrate in the human gastrointestinal tract. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:236-41.

- Salcedo J, Keates S, Pothoulakis C, et. al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Gut. 1997;41:366-70.

General References

- Shea Position Paper Gerding DN,Johnson S, Peterson LR, Mulligan ME Silva J. SHEA Position Paper:Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis; Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1995, 16:459-77

- Kyne L, Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2001; 30:753-77.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been recognized with increased frequency as a cause of nosocomial illness. The frequency and incidence of CDAD varies widely, and is influenced by multiple factors including nosocomial outbreaks, patterns of antimicrobial use, and individual susceptibility. There are no reports of prospective studies by hospitals tracking positive toxin A or A/B and the outcomes of CDAD and its complications.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has analyzed secular trends in the incidence of CDAD, and it reported a steady increase from 1987 to 2001 (1). In this report, 30% of 440 infectious disease physicians who participated in a Web-based poll reported that they are seeing higher rates of CDAD, more severe CDAD, and more relapsing CDAD than in the past. There is an overall impression that there has been an increase in the proportion of cases with severe and fatal complications, and an increase in the relapse rate among affected patients.

In addition to morbidity and mortality, the economic burden of C. difficile infection in terms of delayed discharge and other hospital costs is considerable.

Epidemiology

The frequency and incidence of CDAD varies between hospitals and within a given institution over time. The risk for disease increases in patients with antibiotic exposure, gastrointestinal surgery, increasing length of stay in healthcare settings, serious underlying illness, immuno-compromising conditions, and advanced age.

C. difficile is shed in feces. Any surface, device, or material (e.g., commode, bathing tub, and electronic rectal thermometer) that becomes contaminated with feces may serve as a reservoir for C. difficile spores. Spores are transferred to patients mainly via the hands of healthcare personnel who have touched a contaminated surface or item (2-6).

The Organism and Pathophysiology of C. difficile Diarrhea

C. difficile is a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacillus that is responsible for the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis. C. difficile was first described in 1935 as a component of the fecal flora of healthy newborns and was initially not thought to be pathogenic (7). The bacillus was named difficile because it grows slowly and is difficult to culture. C. difficile is presently responsible for nearly all causes of pseudomembranous colitis and as many as 20% of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea without colitis. Although found in the stool of only 5% of the general population, as many as 21% of adults become colonized with this organism while hospitalized (2,6).

An alteration of the normal colonic microflora, usually caused by antibiotic therapy, is the main factor that predisposes to infection with C. difficile. Almost all antibiotics have been associated with C. difficile diarrhea and colitis. The antibiotics most frequently associated include clindamycin, cephalosporins, ampicillin, and amoxicillin (Table 1) (8).

In addition to antibiotic therapy, older age and severity of underlying disease are important risk factors for C. difficile infection. Other risk factors include the presence of a nasogastric tube, gastrointestinal procedures, acid antisecretory medications, intensive care unit stay, and duration of hospitalization (9).

C. difficile diarrhea is caused primarily by the elaboration of toxins A and B produced by bacterial multiplication within the intestinal lumen. These toxins bind to the colonic mucosa and exert their deleterious effects upon it. The organism rarely damages the colon by direct invasion, and diarrhea is caused by the effects of toxins produced within the intestinal lumen that adhere to the mucosal surface. Most toxigenic isolates produce both toxins, and about 5–25% of isolates produce neither toxin A nor B, and do not cause colitis or diarrhea (3-5).

Clinical Manifestations

Infection with C. difficile may produce a wide range of clinical manifestations, including asymptomatic carriage, mild-to-moderate diarrhea, and fulminant disease with pseudomembranous colitis (10). In patients who develop CDAD, symptoms usually begin soon after colonization. Colonization may occur during antibiotic treatment or up to several weeks after a course of antibiotics. CDAD typically is associated with the passage of frequent, loose bowel movements consistent with proctocolitis. Mucus or occult blood may be present, but visible blood is rare.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CDAD is based on a history of recent or current antibiotic therapy, development of diarrhea or other evidence of acute colitis, and demonstration of infection by toxigenic C. difficile, usually by detection of toxin A or toxin B in stool sample.

Practical Guidelines for Diagnosis of C. difficile Diarrheal Syndromes

- The diagnosis should be suspected in anyone with diarrhea who has received antibiotics within the previous 2 months and/or whose diarrhea begins 72 hours or more after hospitalization.

- When the diagnosis is suspected, a single stool specimen should be sent to the laboratory for testing for the presence of C. difficile and/or its toxins.

- When diarrhea persists despite a negative stool toxin result, one or two additional samples may be sent for testing with the same or different tests (4). Endoscopy is reserved for special situations, such as when a rapid diagnosis is needed and test results are delayed or the test is not highly sensitive, when the patient has ileus and stool is not available, or when other colonic diseases are also a consideration.

There is as yet no simple, inexpensive, rapid, sensitive and specific test for diagnosing C. difficile diarrhea and colitis, nor are all the available tests suitable for adoption by every laboratory (Table 2) (11).

Endoscopic Diagnosis of C. difficile Diarrhea and Colitis

Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are not indicated for most patients with CDAD (10,12). Endoscopy is helpful, however, in special situations, such as when the diagnosis is in doubt or the clinical situation demands rapid diagnosis. The results of endoscopic examination may be normal in patients with mild diarrhea or may show nonspecific colitis in moderate cases. The finding of colonic pseudomembranes in a patient with antibiotic-associated diarrhea is virtually pathognomonic for C. difficile colitis. A few patients without any diagnostic features in the rectosigmoid have pseudomembranes in the more proximal areas of the colon (13). Other endoscopic findings include erythema, edema, friability, and nonspecific colitis with small ulcerations or erosions.

Treatment

The first step in the management of C. difficile diarrhea and colitis is to discontinue the precipitating antibiotics if possible (10,12). Diarrhea resolves in approximately 15–25% of patients without specific anti–C. difficile therapy (14,15). Conservative management alone may not be indicated, however, in patients who are systemically ill or who have multiple medical problems, since it is difficult to predict which patients will improve spontaneously. If it is not possible to discontinue the precipitating antibiotic because of other active infections, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be altered if possible to make use of agents less likely to cause CDAD (e.g., aminoglycosides, trimethoprim, rifampin, or a quinolone).

Antiperistaltic agents, such as diphenoxylate plus atropine (Lomotil), or loperamide (Imodium), and narcotic analgesics should be avoided because they may delay clearance of toxins from the colon and thereby exacerbate toxin-induced colonic injury or precipitate ileus and toxic dilatation (12,16). Specific therapy to eradicate C. difficile should be used in patients with initially severe symptoms and in patients whose symptoms persist despite discontinuation of antibiotic treatment. Although the diagnosis of C. difficile colitis should ideally be established before antimicrobial therapy is implemented, current ACG guidelines recommend that empiric therapy should be initiated in highly suggestive cases of severely ill patients (Table 3 on page 54) (12).

Currently, oral vancomycin or metronidazole, used for 7 to 10 days, are considered first-line therapy by most authors and current guidelines. Metronidazole at a dose of 250 mg 4 times daily is recommended by most authors and ACG guidelines as the drug of choice for the initial treatment of C. difficile colitis (12). These recommendations are largely based on efficacy, lower costs, and concerns about the development of vancomycin-resistant strains. Major disadvantages of metronidazole include a less desirable drug profile and contraindications in children and pregnant women.

Vancomycin, on the other hand, at a dose of 125 mg 4 times daily, is safe and well tolerated and achieves stool levels 20 times the required minimal inhibitory concentration for the treatment of C. difficile. Drawbacks to the use of vancomycin are cost and potential development of vancomycin-resistant strains. The current ACG guidelines consider vancomycin the drug of choice in severely ill patients and in cases in which the use of metronidazole is precluded.

Controlled clinical trials are lacking for patients with fulminant colitis who may not tolerate oral therapy. Administration of metronidazole intravenously or administration of vancomycin by nasogastric tube or rectal enema has been described in small case series (17-20). Intravenous administration of vancomycin is not recommended, because the drug is not excreted in the colon (17).

Management of Recurrent C. difficile Diarrhea

Despite successful initial treatment of CDAD, 15–20% of patients have recurrence of diarrhea in association with a positive stool test for C. difficile toxin. Symptomatic recurrence is rarely due to treatment failure or antimicrobial resistance to metronidazole or vancomycin. Approaches to management include conservative therapy (however, many patients are elderly and infirm and unable to tolerate diarrhea), therapy with specific anti–C. difficile antibiotics, the use of anion-binding resins, therapy with microorganisms (probiotics), and immunoglobulin therapy.

The most common therapy for recurrent C. difficile diarrhea is a second course of the same antibiotic used to treat the initial episode (12). In a large observational study in the United States, 92% of patients with recurrent CDAD responded successfully to a single repeated course of therapy, usually with metronidazole or vancomycin (14). There is evidence to suggest that patients with a history of recurrence have a high risk of further episodes of CDAD after antibiotic therapy is discontinued. There are no data to suggest that sequential episodes become progressively more severe or complicated (21). A variety of treatment schedules have been suggested for patients with multiple recurrences of C. difficile diarrhea. One approach is to give a prolonged course of vancomycin (or metronidazole) using a decreasing dosage schedule followed by pulse therapy (Table 4).

Cholestyramine, an anionexchange resin administered at a dose of 4 grams 3 or 4 times daily for 1 to 2 weeks, binds C. difficile toxins and may be used in conjunction with antibiotics to treat repeated relapses. Because cholestyramine may bind vancomycin as well as toxins, it should be taken at least 2 to 3 hours apart from the vancomycin.

Severe C. difficile Colitis

The incidence of fulminant C. difficile colitis has been reported to be 1.6–3.2% (22). Although recent precise figures from other centers are lacking, it is being recognized as an increasing cause of complications and death. The clinical syndrome of fulminant C. difficile colitis can be recognized with a proper knowledge of the spectrum of disease presentation.

A. Diarrhea: Although diarrhea is the hallmark of C. difficile colitis, it is not invariably present, and its absence may lead to diagnostic confusion. When diarrhea is absent, this appears to be secondary to severe colonic dysmotility. Even when present, diarrhea may be perceived to be a minor component of a nonspecific septic picture.

B. Severe Disease: Fulminant colitis is an unusual form of C. difficile infection, occurring in only 3% of patients but accounting for virtually all serious complications. Patients with more severe forms of the disease may present with or without diarrhea. When patients develop colitis localized to the cecum and right side of the colon, diarrhea may be minimal or absent. In the absence of diarrhea, the only clues to diagnosis may be systemic signs of toxicity (fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and/or volume depletion).

An elevated white blood cell count may be an important clue to impending fulminant C. difficile colitis. The rapid elevation of the peripheral white cell count (commonly as high as 30,000 to 50,000) with a significant excess of bands and sometimes more immature forms often precedes hemodynamic instability and the development of organ dysfunction. Even in patients who are mildly symptomatic for an extended period, sudden and unexpected progression to shock may occur. It is difficult to predict those patients who may not respond to medical treatment. Hence, early warning signs such as a leukemoid reaction may be invaluable.

Hypotension is a late finding and can be resistant to vasopressor support. Abdominal signs range from distention to generalized tenderness with guarding. Colonic perforation is usually accompanied by abdominal rigidity, involuntary guarding, rebound tenderness, and absent bowel sounds. Free air may be revealed on abdominal radiographs. Any suspicion of perforation in this setting should prompt immediate surgical consultation. Death generally occurs before free air and perforation can occur. In one study, contrary to most other literature, perforation was found to be rare (22).

Abdominal radiography may reveal a dilated colon (>7 cm in its greatest diameter), consistent with toxic megacolon. Patients with megacolon may have an associated small bowel ileus with dilated small intestine on plain abdominal radiographs, with air-fluid levels mimicking small intestinal obstruction or ischemia. CT without contrast and endoscopy can quickly diagnose or at least strongly suggest fulminant C.difficile colitis. CT scan findings include evidence of ascites, colonic wall thickening and/or dilatation. These findings may prove helpful in categorizing the severity of the colitis.

More aggressive intervention in medically unresponsive patients, including rapid identification of patients failing to respond to medical therapy, is crucial to a positive outcome, and early surgical intervention should be done in this group (Figures 1-3).

It is important that everyone involved with patient care in hospitals, nursing homes, and skilled nursing facilities be educated about the organism and its epidemiology, rational approaches to the treatment and care of patients with C. difficile diarrhea, the importance of hand washing between contact with patients, the use of gloves when caring for a patient with C. difficile diarrhea, and the avoidance of the unnecessary use of antimicrobials.

Conclusion

Recent years have raised concerns over rising incidence and serious complication rates of CDAD in North American hospitals (22,23). The Canadian Medical Association journal published a report in 2004 detailing an outbreak of CDAD involving several hospitals in Montreal. The introduction of new hypervirulent and highly transmissible strains of C. difficile has been postulated as the possible cause for the outbreak (24). A deteriorating infrastructure, inadequate infection control practices, the increasing number of debilitated patients, an aging population, and hypervirulent strains were all felt to be likely contributors to recent outbreaks in Canada (25).

Two epidemiological investigations in the United States and Canada (24,26) independently examined samples of C. difficile and found that a mutated version of the “wild” strain was responsible for outbreaks in Quebec and increased rates of CDAD in hospitals in the United States recently (22,23). Clinical epidemiologists at the CDC investigated C. difficile isolates from hospitals in the United States with recent (i.e., 2001–2004) CDAD outbreaks (22,23). The report indicates the emergence of a new epidemic strain, “BI” (distinct from the “J” strain of 1989–1992), which may be responsible for the recent increase in rates and apparent severity of CDAD (26).

CDAD and colitis in most cases can be treated by the administration of metronidazole or vancomycin. In some patients severe life-threatening toxicity develops despite appropriate and timely medical treatment, and surgical intervention is necessary. Systemic symptoms of infection with C. difficile are reported not to derive from bacteremia, colonic perforation or ischemia, but from toxin-induced inflammatory mediators released from the colon (27-29). Early surgical intervention should be employed in refractory cases of severe disease. Surgical intervention is far from ideal, however, and carries a very high rate of complications and significant risk of mortality (22). The future clinical approach to the treatment of nosocomial C. difficile colitis may eventually involve specific antitoxin hyperimmunoglobulins and inhibitors of the inflammatory cascade (28,30,31).

References

- Archibald LK, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Secular trend in hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile disease in the United States; 1987-2001. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1585-9.

- Fekety R. Antibiotic-associated colitis. In: Mandell G, Bennet JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingston; 1996:978-806.

- Mitty RD, LaMont T. Clostridium difficile diarrhea: Pathogenesis, epidemiology, and treatment. Gastroenterologist. 1994;2:61-9.

- Bartlett JG. Clostridium difficile: History of its role as an enteric pathogen and the current state of knowledge about the organism. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl 4):265-72.

- Johnson S, Gerding D. Clostridium difficile. In: Mayhall CG, ed. Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:99-408.

- Mcfarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204-10.

- Hall IC, O Toole E. Intestinal Flora in new-born infants: With a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficile. Am J Dis Child. 1935;49:390-402.

- Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. In: Wolfe MM, ed. Gastrointestinal Pharmacotherapy. Philadelphia, Pa.: WB Saunders; 1993:199-212.

- Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 1998;40:1-15.

- Kelly CP, Pothoulakas C, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile colitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:257-62.

- Linevsky JK, Kelly CP. Clostridium difficile colitis. In: Lamont JT, ed. Gastrointestinal Infections: Diagnosis and Management. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997:293-325.

- Fekety R. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea and colitis. American College of Gastroenetrology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:739-50.

- Tedesco FJ, Corless JK, Brownstein RE. Rectal sparing in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis: A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1259-60.

- Olson MM, Shanholtzer CJ, Lee JT Jr, Gerding DN. Ten years of prospective Clostridium difficile-associated disease surveillance and treatment at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, 1982-1991. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15: 371-81.

- Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhoea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-6.

- Walley T, Milson D. Loperamide-related toxic megacolon in Clostridium difficile colitis. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:582.

- Malnick SD, Zimhony O. Treatment of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1767-75.

- Sehgal M, Kyne L. Clostridium difficile disease. Curr Treatment Options Infect Dis. 2002;4:201-10.

- Apisarnthanarak A, Razavi B, Mundy LM. Adjunctive intracolonic vancomycin for severe Clostridium difficile colitis: case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:690-6.

- Friendenberg F, Fernandez A, Kaul V, Niami P, Levine GM. Intravenous metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1176-80.

- Fekety R, McFarland LV, Surawicz CMGreenberg, RN, Elmer GW, Mulligan ME. Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324-33.

- Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363-72.

- Morris AM, Jobe BA, Sontey, M, Sheppard BC, Deveney CW, Deveney KE. Clostridium difficile colitis: an increasingly aggressive iatrogenic disease? Arch Surg. 2002;137:1096-100.

- Eggerston L, Sibbald B. Hospitals battling outbreaks of C. difficile. CMAJ. 2004;171:19-21.

- Valiquette L, Low DE, Pepin J, McGeer A. Clostridium difficile infection in hospitals: a brewing storm. CMAJ. 2004;171:27-9.

- McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, et al. Emergence of an epidemic strain of Clostridium difficile in the United States, 2001-4: Potential role for virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance traits. Infectious Diseases Society of America 42th Annual Meeting. Boston, MA, September 30 – October 3, 2004. Abstract # LB-2.

- Flegel W, Muller F, Daubener W, Fischer HG, Hadding U, Northoff H. Cytokine response by human monocytes to Clostridium difficile toxin A and toxin B. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3659-66.

- Castagliuolo I, Keates A, Qiu B, et al. Increased substance P responses in dorsal root ganglia, intestinal macrophages during Clostridium difficile toxin A enteritis in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4788-93.

- Castagliuolo I, Keates A, Wang C, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin A stimulates macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 production in rat intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:6039-45.

- Kelly C, Chetham S, Keates S, et al. Survival of anti-Clostridium difficile bovine immunoglobulin concentrate in the human gastrointestinal tract. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:236-41.

- Salcedo J, Keates S, Pothoulakis C, et. al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Gut. 1997;41:366-70.

General References

- Shea Position Paper Gerding DN,Johnson S, Peterson LR, Mulligan ME Silva J. SHEA Position Paper:Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis; Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1995, 16:459-77

- Kyne L, Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2001; 30:753-77.