User login

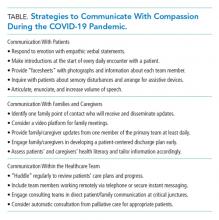

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is the health crisis of our generation and will inevitably leave a lasting mark on how we practice medicine.1,2 It has already rapidly changed the way we communicate with patients, families, and colleagues. From the explosion of virtual care—which has been accelerated by need and new reimbursement policies3—to the physical barriers created by personal protective equipment (PPE) and no-visitor policies, the landscape of caring for hospitalized patients has seismically shifted in a few short months. At its core, the practice of medicine is about human connection—a connection between healers and the sick—and should remain as such to provide compassionate care to patients and their loved ones.4,5 In this perspective, we discuss challenges arising from communication barriers in the time of COVID-19 and opportunities to overcome them by preserving human connection to deliver high-quality care (Table).

COMMUNICATION WITH PATIENTS

While critically important to prevent transmission of the COVID-19 pathogen (ie, SARS-CoV-2), physical distancing and PPE create myriad challenges to achieving effective communication between healthcare providers and patients. Telemedicine has been leveraged to allow distanced communication between patients with COVID-19 and their providers from separate rooms. For face-to-face conversations, physical barriers, including distance between individuals and the wearing of face masks, impose new types of hindrances to nonverbal and verbal communication.

Challenges

Nonverbal communication helps build the therapeutic alliance and influences patient adherence to care plans, satisfaction, trust, and clinical outcomes.6,7 Expressions of emotion and reciprocity of nonverbal communication serve as important foundations for physician-patient encounters.6 Face masks, a necessity to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, lead to fewer facial cues and may impede the ability to express and recognize emotional cues for patients and providers. A study of over 1,000 patients randomized to mask-wearing and non–mask-wearing physicians revealed a significant and negative effect on patient perception of physician empathy in consultations performed by mask-wearing physicians.8 Additionally, simple handshakes that convey respect and appreciation are no longer practiced.

Verbal communication is also affected by measures designed to reduce infection. The face mask and face shield worn by clinicians caring for patients with respiratory illnesses like COVID-19 diminish the volume and clarity of the spoken word. This is particularly problematic for patients who have sensory disturbances like hearing impairment. Additionally, these patients may rely on lipreading to effectively understand others, a strategy lost once the face mask is donned.

Opportunities

Healthcare providers may respond to nonverbal communication impediments by explicitly shifting nonverbal to verbal communication. For instance, when delivering serious news, a physician might previously have “mirrored” the patient’s sadness through a light touch on the hand and facial expressions congruent with that emotion. With physical distancing and PPE, the physician may instead express empathy through verbal statements such as acknowledging, validating, and respecting the patient’s emotions; making supportive statements; or exploring the patient’s feelings. The physician may also thank the patient for providing their input for the conversation.

Physicians should introduce themselves at the start of every daily encounter with a patient since there may be few distinct features above the face mask to distinguish the numerous individuals on a healthcare team. Some medical teams have provided “facesheets” with photographs and information about each member in an effort to humanize the team and connect more genuinely with the patient. In some cases, this may be the only way for a patient to see their healthcare providers’ faces.

To address obstacles to effective verbal communication, physicians should inquire about patients’ possible sensory disturbances on admission and, if necessary, arrange for hearing aids or other assistive devices. When communicating, physicians should articulate, enunciate, and increase volume to overcome the physical barrier created by the face mask. They should speak slowly, use plain language without jargon, and intentionally pause to check for understanding using the teach-back method.9

COMMUNICATION WITH FAMILIES AND CAREGIVERS

Challenges

With the aim of mitigating SARS-CoV-2 transmission, most healthcare systems have implemented no-visitor policies for hospitalized patients. This often leads to feelings of isolation among patients and their families. Goals-of-care discussions for COVID-19 and other serious diagnoses such as cancer can become even more difficult because family members often cannot witness how ill patients have become and clinicians cannot easily communicate virtually with multiple family members simultaneously.

Lack of family at the bedside also makes critical activities, such as discharge planning and education, more vulnerable to poor coordination and medical errors.10 Patients who are continuing to recover from acute illness may be expected to learn the details of home infusion for intravenous antibiotics, tracheostomy care, or specialized nutritional feeds. Without caregiver support, the patient may be at risk for readmission or other untoward safety events.

Opportunities

Several strategies may be used to improve virtual communication with families. The healthcare team should identify one family point of contact (ideally with the durable power of attorney for healthcare) who will receive and disseminate to others information about the patient’s status. This reduces the potential for multiple telephone conversations. We have witnessed some remarkable family points of contact call many family members to relay medical updates and moderate discussion. Care teams may decide to call the family contact during rounds so that they may listen in on the conversation with the patient or call after rounds to provide succinct updates. Family meetings may benefit greatly if conducted through a video platform, when possible, particularly if significant interval events have occurred. Connection through video allows eye contact and recognition of other nonverbal cues, as well as allowing findings like diagnostic images to be shared.

Because of increased anxiety associated with isolation, we recommend that one member of the primary healthcare team conduct telephone updates to the family point of contact on at least a daily basis. This simple act reduces potential for disjointed or discrepant messages from the healthcare team.11 It also demonstrates the value of keeping those individuals most important to the patient informed and has been shown to increase satisfaction with care and perceived effectiveness of meeting informational needs.12

Regarding discharge planning, physicians should engage the patient and family/caregivers in developing a patient-centered plan as early in the hospital stay as possible. The adage “discharge planning starts at admission” has never been more relevant. The team should avoid assumptions about patient/family sophistication for understanding complex healthcare concepts. Rather, physicians should assess patients’ and caregivers’ health literacy at the beginning of a hospital stay by asking simple, validated questions in a nonjudgmental way.13,14 This valuable information then allows the team to tailor medical information and discharge education appropriately for both patients and caregivers.

COMMUNICATION WITHIN THE HEALTHCARE TEAM

Challenges

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, various members of the healthcare team may be working remotely, and therefore, team members may feel less connected with each other. This could lead to a loss of camaraderie and fellowship within the team, as well as depersonalization, one of the main facets of burnout.15 Even if colocalized in the same area, those wearing face masks may experience disconnection and depersonalization. In an anecdote at our medical center, one clinician did not know what her team members’ faces looked like until they removed their masks for a moment to have a snack just before the end of the rotation.

In addition, healthcare systems have witnessed an increase in the volume of electronic consultations in which faculty and house staff review the patient’s medical record and render medical decision-making and recommendations without physically examining or interviewing the patient at the bedside. The purpose of this is twofold: to reduce the risk of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 and to conserve PPE. Electronic consultations could threaten to reduce collaborative communication and teaching among primary and consulting teams, which may lead to greater misunderstanding, less-effective patient care, and decreased satisfaction within the healthcare team.

Opportunities

Now more than ever, physicians should purposefully engage in regular communication with the multidisciplinary healthcare team that includes nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and other critical members. Because many of these individuals may now be working remotely or not joining in-person rounds, several strategies are needed to ensure care coordination within the primary healthcare team. For example, all members should “huddle” at least once daily to review each patient’s care and progress in meeting discharge goals. Team members who are working remotely should be dialed into these huddles and included in coordinating the plan for the day. While in-person multidisciplinary rounds may be temporarily halted to allow for physical distancing of staff, physician leaders can still encourage regular check-ins and updates throughout the day with multidisciplinary team members by other means, such as discussions by phone or a secure instant messenger, if available.

Another strategy to improve care coordination is to engage consulting teams in direct patient/family communication at critical junctures. For example, when a patient’s renal failure has gotten severe enough that dialysis is a consideration, the primary team may ask the nephrology consult service to participate in a joint telephone discussion with the family about risks, benefits, and alternatives to renal replacement therapy. Additionally, our palliative care consult service volunteered to be automatically consulted for all COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit and high-risk COVID-19 patients on the acute care wards because of the disease’s high potential morbidity and mortality. Their roles included proactively confirming the patient’s surrogate decision maker, reviewing the patient’s decision-making capacity, eliciting specific goals of care and life-sustaining treatment preferences, and establishing relationships with the family. They also conducted daily huddles with the respective teams, another approach that fostered high-quality, collaborative care.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to change the approaches we usually employ to interact with patients and their loved ones, as well as healthcare team members, but it has not changed the heart of medicine, which is to heal. Here we provide tangible and discrete strategies to achieve this goal through clear and compassionate communication, including shifting nonverbal to verbal communication with patients, speaking at least daily to one family point of contact, ensuring early and tailored discharge planning, emphasizing continued close care coordination among the multidisciplinary team, and thoughtfully engaging consultants in patient/family communication. We hope this guidance will assist us in striving to cultivate connection with our patients, their loved ones, and each other, just as we have always sought to do. With these strategies in mind, coupled with a continued focus on patient- and family-centered care for hospitalized patients, no amount of distance or PPE will diminish the power of human connection.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their colleagues—the physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, clerks, custodial staff, security, and administrative professionals, to name a few—of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System for their collaboration, dedication, and grace in this time of crisis. The authors are indebted to the patients and their loved ones for putting their trust in their team, for teaching team members, and for providing the privilege of being a part of their lives.

Disclosures

The authors reported having nothing to disclose.

1. Ross JE. Resident response during pandemic: this is our time [online first]. Ann Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1240

2. Berwick DM. Choices for the “new normal” [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6949.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. CMS.gov. Mar 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak. Accessed May 09, 2020.

4. Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70‐81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.19003.

5. Haverfield MC, Tierney A, Schwartz R, et al. Can patient-provider interpersonal interventions achieve the quadruple aim of healthcare? a systematic review [online first]. J Gen Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05525-2.

6. Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, Sluyter D. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits: mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S28-S34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00306.x.

7. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):315-318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.005.

8. Wong CK, Yip BH, Mercer S, et al. Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-200.

9. Talevski J, Wong Shee A, Rasmussen B, Kemp G, Beauchamp A. Teach-back: a systematic review of implementation and impacts. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231350.

10. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228.

11. Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(4):317-324.

12. Medland JJ, Ferrans CE. Effectiveness of a structured communication program for family members of patients in an ICU. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(1):24-29.

13. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594.

14. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874-877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x.

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516‐529. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752.

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is the health crisis of our generation and will inevitably leave a lasting mark on how we practice medicine.1,2 It has already rapidly changed the way we communicate with patients, families, and colleagues. From the explosion of virtual care—which has been accelerated by need and new reimbursement policies3—to the physical barriers created by personal protective equipment (PPE) and no-visitor policies, the landscape of caring for hospitalized patients has seismically shifted in a few short months. At its core, the practice of medicine is about human connection—a connection between healers and the sick—and should remain as such to provide compassionate care to patients and their loved ones.4,5 In this perspective, we discuss challenges arising from communication barriers in the time of COVID-19 and opportunities to overcome them by preserving human connection to deliver high-quality care (Table).

COMMUNICATION WITH PATIENTS

While critically important to prevent transmission of the COVID-19 pathogen (ie, SARS-CoV-2), physical distancing and PPE create myriad challenges to achieving effective communication between healthcare providers and patients. Telemedicine has been leveraged to allow distanced communication between patients with COVID-19 and their providers from separate rooms. For face-to-face conversations, physical barriers, including distance between individuals and the wearing of face masks, impose new types of hindrances to nonverbal and verbal communication.

Challenges

Nonverbal communication helps build the therapeutic alliance and influences patient adherence to care plans, satisfaction, trust, and clinical outcomes.6,7 Expressions of emotion and reciprocity of nonverbal communication serve as important foundations for physician-patient encounters.6 Face masks, a necessity to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, lead to fewer facial cues and may impede the ability to express and recognize emotional cues for patients and providers. A study of over 1,000 patients randomized to mask-wearing and non–mask-wearing physicians revealed a significant and negative effect on patient perception of physician empathy in consultations performed by mask-wearing physicians.8 Additionally, simple handshakes that convey respect and appreciation are no longer practiced.

Verbal communication is also affected by measures designed to reduce infection. The face mask and face shield worn by clinicians caring for patients with respiratory illnesses like COVID-19 diminish the volume and clarity of the spoken word. This is particularly problematic for patients who have sensory disturbances like hearing impairment. Additionally, these patients may rely on lipreading to effectively understand others, a strategy lost once the face mask is donned.

Opportunities

Healthcare providers may respond to nonverbal communication impediments by explicitly shifting nonverbal to verbal communication. For instance, when delivering serious news, a physician might previously have “mirrored” the patient’s sadness through a light touch on the hand and facial expressions congruent with that emotion. With physical distancing and PPE, the physician may instead express empathy through verbal statements such as acknowledging, validating, and respecting the patient’s emotions; making supportive statements; or exploring the patient’s feelings. The physician may also thank the patient for providing their input for the conversation.

Physicians should introduce themselves at the start of every daily encounter with a patient since there may be few distinct features above the face mask to distinguish the numerous individuals on a healthcare team. Some medical teams have provided “facesheets” with photographs and information about each member in an effort to humanize the team and connect more genuinely with the patient. In some cases, this may be the only way for a patient to see their healthcare providers’ faces.

To address obstacles to effective verbal communication, physicians should inquire about patients’ possible sensory disturbances on admission and, if necessary, arrange for hearing aids or other assistive devices. When communicating, physicians should articulate, enunciate, and increase volume to overcome the physical barrier created by the face mask. They should speak slowly, use plain language without jargon, and intentionally pause to check for understanding using the teach-back method.9

COMMUNICATION WITH FAMILIES AND CAREGIVERS

Challenges

With the aim of mitigating SARS-CoV-2 transmission, most healthcare systems have implemented no-visitor policies for hospitalized patients. This often leads to feelings of isolation among patients and their families. Goals-of-care discussions for COVID-19 and other serious diagnoses such as cancer can become even more difficult because family members often cannot witness how ill patients have become and clinicians cannot easily communicate virtually with multiple family members simultaneously.

Lack of family at the bedside also makes critical activities, such as discharge planning and education, more vulnerable to poor coordination and medical errors.10 Patients who are continuing to recover from acute illness may be expected to learn the details of home infusion for intravenous antibiotics, tracheostomy care, or specialized nutritional feeds. Without caregiver support, the patient may be at risk for readmission or other untoward safety events.

Opportunities

Several strategies may be used to improve virtual communication with families. The healthcare team should identify one family point of contact (ideally with the durable power of attorney for healthcare) who will receive and disseminate to others information about the patient’s status. This reduces the potential for multiple telephone conversations. We have witnessed some remarkable family points of contact call many family members to relay medical updates and moderate discussion. Care teams may decide to call the family contact during rounds so that they may listen in on the conversation with the patient or call after rounds to provide succinct updates. Family meetings may benefit greatly if conducted through a video platform, when possible, particularly if significant interval events have occurred. Connection through video allows eye contact and recognition of other nonverbal cues, as well as allowing findings like diagnostic images to be shared.

Because of increased anxiety associated with isolation, we recommend that one member of the primary healthcare team conduct telephone updates to the family point of contact on at least a daily basis. This simple act reduces potential for disjointed or discrepant messages from the healthcare team.11 It also demonstrates the value of keeping those individuals most important to the patient informed and has been shown to increase satisfaction with care and perceived effectiveness of meeting informational needs.12

Regarding discharge planning, physicians should engage the patient and family/caregivers in developing a patient-centered plan as early in the hospital stay as possible. The adage “discharge planning starts at admission” has never been more relevant. The team should avoid assumptions about patient/family sophistication for understanding complex healthcare concepts. Rather, physicians should assess patients’ and caregivers’ health literacy at the beginning of a hospital stay by asking simple, validated questions in a nonjudgmental way.13,14 This valuable information then allows the team to tailor medical information and discharge education appropriately for both patients and caregivers.

COMMUNICATION WITHIN THE HEALTHCARE TEAM

Challenges

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, various members of the healthcare team may be working remotely, and therefore, team members may feel less connected with each other. This could lead to a loss of camaraderie and fellowship within the team, as well as depersonalization, one of the main facets of burnout.15 Even if colocalized in the same area, those wearing face masks may experience disconnection and depersonalization. In an anecdote at our medical center, one clinician did not know what her team members’ faces looked like until they removed their masks for a moment to have a snack just before the end of the rotation.

In addition, healthcare systems have witnessed an increase in the volume of electronic consultations in which faculty and house staff review the patient’s medical record and render medical decision-making and recommendations without physically examining or interviewing the patient at the bedside. The purpose of this is twofold: to reduce the risk of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 and to conserve PPE. Electronic consultations could threaten to reduce collaborative communication and teaching among primary and consulting teams, which may lead to greater misunderstanding, less-effective patient care, and decreased satisfaction within the healthcare team.

Opportunities

Now more than ever, physicians should purposefully engage in regular communication with the multidisciplinary healthcare team that includes nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and other critical members. Because many of these individuals may now be working remotely or not joining in-person rounds, several strategies are needed to ensure care coordination within the primary healthcare team. For example, all members should “huddle” at least once daily to review each patient’s care and progress in meeting discharge goals. Team members who are working remotely should be dialed into these huddles and included in coordinating the plan for the day. While in-person multidisciplinary rounds may be temporarily halted to allow for physical distancing of staff, physician leaders can still encourage regular check-ins and updates throughout the day with multidisciplinary team members by other means, such as discussions by phone or a secure instant messenger, if available.

Another strategy to improve care coordination is to engage consulting teams in direct patient/family communication at critical junctures. For example, when a patient’s renal failure has gotten severe enough that dialysis is a consideration, the primary team may ask the nephrology consult service to participate in a joint telephone discussion with the family about risks, benefits, and alternatives to renal replacement therapy. Additionally, our palliative care consult service volunteered to be automatically consulted for all COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit and high-risk COVID-19 patients on the acute care wards because of the disease’s high potential morbidity and mortality. Their roles included proactively confirming the patient’s surrogate decision maker, reviewing the patient’s decision-making capacity, eliciting specific goals of care and life-sustaining treatment preferences, and establishing relationships with the family. They also conducted daily huddles with the respective teams, another approach that fostered high-quality, collaborative care.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to change the approaches we usually employ to interact with patients and their loved ones, as well as healthcare team members, but it has not changed the heart of medicine, which is to heal. Here we provide tangible and discrete strategies to achieve this goal through clear and compassionate communication, including shifting nonverbal to verbal communication with patients, speaking at least daily to one family point of contact, ensuring early and tailored discharge planning, emphasizing continued close care coordination among the multidisciplinary team, and thoughtfully engaging consultants in patient/family communication. We hope this guidance will assist us in striving to cultivate connection with our patients, their loved ones, and each other, just as we have always sought to do. With these strategies in mind, coupled with a continued focus on patient- and family-centered care for hospitalized patients, no amount of distance or PPE will diminish the power of human connection.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their colleagues—the physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, clerks, custodial staff, security, and administrative professionals, to name a few—of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System for their collaboration, dedication, and grace in this time of crisis. The authors are indebted to the patients and their loved ones for putting their trust in their team, for teaching team members, and for providing the privilege of being a part of their lives.

Disclosures

The authors reported having nothing to disclose.

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is the health crisis of our generation and will inevitably leave a lasting mark on how we practice medicine.1,2 It has already rapidly changed the way we communicate with patients, families, and colleagues. From the explosion of virtual care—which has been accelerated by need and new reimbursement policies3—to the physical barriers created by personal protective equipment (PPE) and no-visitor policies, the landscape of caring for hospitalized patients has seismically shifted in a few short months. At its core, the practice of medicine is about human connection—a connection between healers and the sick—and should remain as such to provide compassionate care to patients and their loved ones.4,5 In this perspective, we discuss challenges arising from communication barriers in the time of COVID-19 and opportunities to overcome them by preserving human connection to deliver high-quality care (Table).

COMMUNICATION WITH PATIENTS

While critically important to prevent transmission of the COVID-19 pathogen (ie, SARS-CoV-2), physical distancing and PPE create myriad challenges to achieving effective communication between healthcare providers and patients. Telemedicine has been leveraged to allow distanced communication between patients with COVID-19 and their providers from separate rooms. For face-to-face conversations, physical barriers, including distance between individuals and the wearing of face masks, impose new types of hindrances to nonverbal and verbal communication.

Challenges

Nonverbal communication helps build the therapeutic alliance and influences patient adherence to care plans, satisfaction, trust, and clinical outcomes.6,7 Expressions of emotion and reciprocity of nonverbal communication serve as important foundations for physician-patient encounters.6 Face masks, a necessity to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, lead to fewer facial cues and may impede the ability to express and recognize emotional cues for patients and providers. A study of over 1,000 patients randomized to mask-wearing and non–mask-wearing physicians revealed a significant and negative effect on patient perception of physician empathy in consultations performed by mask-wearing physicians.8 Additionally, simple handshakes that convey respect and appreciation are no longer practiced.

Verbal communication is also affected by measures designed to reduce infection. The face mask and face shield worn by clinicians caring for patients with respiratory illnesses like COVID-19 diminish the volume and clarity of the spoken word. This is particularly problematic for patients who have sensory disturbances like hearing impairment. Additionally, these patients may rely on lipreading to effectively understand others, a strategy lost once the face mask is donned.

Opportunities

Healthcare providers may respond to nonverbal communication impediments by explicitly shifting nonverbal to verbal communication. For instance, when delivering serious news, a physician might previously have “mirrored” the patient’s sadness through a light touch on the hand and facial expressions congruent with that emotion. With physical distancing and PPE, the physician may instead express empathy through verbal statements such as acknowledging, validating, and respecting the patient’s emotions; making supportive statements; or exploring the patient’s feelings. The physician may also thank the patient for providing their input for the conversation.

Physicians should introduce themselves at the start of every daily encounter with a patient since there may be few distinct features above the face mask to distinguish the numerous individuals on a healthcare team. Some medical teams have provided “facesheets” with photographs and information about each member in an effort to humanize the team and connect more genuinely with the patient. In some cases, this may be the only way for a patient to see their healthcare providers’ faces.

To address obstacles to effective verbal communication, physicians should inquire about patients’ possible sensory disturbances on admission and, if necessary, arrange for hearing aids or other assistive devices. When communicating, physicians should articulate, enunciate, and increase volume to overcome the physical barrier created by the face mask. They should speak slowly, use plain language without jargon, and intentionally pause to check for understanding using the teach-back method.9

COMMUNICATION WITH FAMILIES AND CAREGIVERS

Challenges

With the aim of mitigating SARS-CoV-2 transmission, most healthcare systems have implemented no-visitor policies for hospitalized patients. This often leads to feelings of isolation among patients and their families. Goals-of-care discussions for COVID-19 and other serious diagnoses such as cancer can become even more difficult because family members often cannot witness how ill patients have become and clinicians cannot easily communicate virtually with multiple family members simultaneously.

Lack of family at the bedside also makes critical activities, such as discharge planning and education, more vulnerable to poor coordination and medical errors.10 Patients who are continuing to recover from acute illness may be expected to learn the details of home infusion for intravenous antibiotics, tracheostomy care, or specialized nutritional feeds. Without caregiver support, the patient may be at risk for readmission or other untoward safety events.

Opportunities

Several strategies may be used to improve virtual communication with families. The healthcare team should identify one family point of contact (ideally with the durable power of attorney for healthcare) who will receive and disseminate to others information about the patient’s status. This reduces the potential for multiple telephone conversations. We have witnessed some remarkable family points of contact call many family members to relay medical updates and moderate discussion. Care teams may decide to call the family contact during rounds so that they may listen in on the conversation with the patient or call after rounds to provide succinct updates. Family meetings may benefit greatly if conducted through a video platform, when possible, particularly if significant interval events have occurred. Connection through video allows eye contact and recognition of other nonverbal cues, as well as allowing findings like diagnostic images to be shared.

Because of increased anxiety associated with isolation, we recommend that one member of the primary healthcare team conduct telephone updates to the family point of contact on at least a daily basis. This simple act reduces potential for disjointed or discrepant messages from the healthcare team.11 It also demonstrates the value of keeping those individuals most important to the patient informed and has been shown to increase satisfaction with care and perceived effectiveness of meeting informational needs.12

Regarding discharge planning, physicians should engage the patient and family/caregivers in developing a patient-centered plan as early in the hospital stay as possible. The adage “discharge planning starts at admission” has never been more relevant. The team should avoid assumptions about patient/family sophistication for understanding complex healthcare concepts. Rather, physicians should assess patients’ and caregivers’ health literacy at the beginning of a hospital stay by asking simple, validated questions in a nonjudgmental way.13,14 This valuable information then allows the team to tailor medical information and discharge education appropriately for both patients and caregivers.

COMMUNICATION WITHIN THE HEALTHCARE TEAM

Challenges

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, various members of the healthcare team may be working remotely, and therefore, team members may feel less connected with each other. This could lead to a loss of camaraderie and fellowship within the team, as well as depersonalization, one of the main facets of burnout.15 Even if colocalized in the same area, those wearing face masks may experience disconnection and depersonalization. In an anecdote at our medical center, one clinician did not know what her team members’ faces looked like until they removed their masks for a moment to have a snack just before the end of the rotation.

In addition, healthcare systems have witnessed an increase in the volume of electronic consultations in which faculty and house staff review the patient’s medical record and render medical decision-making and recommendations without physically examining or interviewing the patient at the bedside. The purpose of this is twofold: to reduce the risk of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 and to conserve PPE. Electronic consultations could threaten to reduce collaborative communication and teaching among primary and consulting teams, which may lead to greater misunderstanding, less-effective patient care, and decreased satisfaction within the healthcare team.

Opportunities

Now more than ever, physicians should purposefully engage in regular communication with the multidisciplinary healthcare team that includes nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and other critical members. Because many of these individuals may now be working remotely or not joining in-person rounds, several strategies are needed to ensure care coordination within the primary healthcare team. For example, all members should “huddle” at least once daily to review each patient’s care and progress in meeting discharge goals. Team members who are working remotely should be dialed into these huddles and included in coordinating the plan for the day. While in-person multidisciplinary rounds may be temporarily halted to allow for physical distancing of staff, physician leaders can still encourage regular check-ins and updates throughout the day with multidisciplinary team members by other means, such as discussions by phone or a secure instant messenger, if available.

Another strategy to improve care coordination is to engage consulting teams in direct patient/family communication at critical junctures. For example, when a patient’s renal failure has gotten severe enough that dialysis is a consideration, the primary team may ask the nephrology consult service to participate in a joint telephone discussion with the family about risks, benefits, and alternatives to renal replacement therapy. Additionally, our palliative care consult service volunteered to be automatically consulted for all COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit and high-risk COVID-19 patients on the acute care wards because of the disease’s high potential morbidity and mortality. Their roles included proactively confirming the patient’s surrogate decision maker, reviewing the patient’s decision-making capacity, eliciting specific goals of care and life-sustaining treatment preferences, and establishing relationships with the family. They also conducted daily huddles with the respective teams, another approach that fostered high-quality, collaborative care.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to change the approaches we usually employ to interact with patients and their loved ones, as well as healthcare team members, but it has not changed the heart of medicine, which is to heal. Here we provide tangible and discrete strategies to achieve this goal through clear and compassionate communication, including shifting nonverbal to verbal communication with patients, speaking at least daily to one family point of contact, ensuring early and tailored discharge planning, emphasizing continued close care coordination among the multidisciplinary team, and thoughtfully engaging consultants in patient/family communication. We hope this guidance will assist us in striving to cultivate connection with our patients, their loved ones, and each other, just as we have always sought to do. With these strategies in mind, coupled with a continued focus on patient- and family-centered care for hospitalized patients, no amount of distance or PPE will diminish the power of human connection.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their colleagues—the physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, clerks, custodial staff, security, and administrative professionals, to name a few—of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System for their collaboration, dedication, and grace in this time of crisis. The authors are indebted to the patients and their loved ones for putting their trust in their team, for teaching team members, and for providing the privilege of being a part of their lives.

Disclosures

The authors reported having nothing to disclose.

1. Ross JE. Resident response during pandemic: this is our time [online first]. Ann Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1240

2. Berwick DM. Choices for the “new normal” [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6949.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. CMS.gov. Mar 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak. Accessed May 09, 2020.

4. Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70‐81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.19003.

5. Haverfield MC, Tierney A, Schwartz R, et al. Can patient-provider interpersonal interventions achieve the quadruple aim of healthcare? a systematic review [online first]. J Gen Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05525-2.

6. Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, Sluyter D. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits: mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S28-S34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00306.x.

7. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):315-318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.005.

8. Wong CK, Yip BH, Mercer S, et al. Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-200.

9. Talevski J, Wong Shee A, Rasmussen B, Kemp G, Beauchamp A. Teach-back: a systematic review of implementation and impacts. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231350.

10. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228.

11. Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(4):317-324.

12. Medland JJ, Ferrans CE. Effectiveness of a structured communication program for family members of patients in an ICU. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(1):24-29.

13. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594.

14. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874-877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x.

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516‐529. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752.

1. Ross JE. Resident response during pandemic: this is our time [online first]. Ann Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1240

2. Berwick DM. Choices for the “new normal” [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6949.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. CMS.gov. Mar 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak. Accessed May 09, 2020.

4. Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70‐81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.19003.

5. Haverfield MC, Tierney A, Schwartz R, et al. Can patient-provider interpersonal interventions achieve the quadruple aim of healthcare? a systematic review [online first]. J Gen Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05525-2.

6. Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, Sluyter D. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits: mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S28-S34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00306.x.

7. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):315-318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.005.

8. Wong CK, Yip BH, Mercer S, et al. Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-200.

9. Talevski J, Wong Shee A, Rasmussen B, Kemp G, Beauchamp A. Teach-back: a systematic review of implementation and impacts. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231350.

10. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228.

11. Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(4):317-324.

12. Medland JJ, Ferrans CE. Effectiveness of a structured communication program for family members of patients in an ICU. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(1):24-29.

13. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594.

14. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874-877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x.

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516‐529. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine