User login

Beyond a Purple Journal: Improving Hospital-Based Addiction Care

Rosa* was one of my first patients as an intern rotating at the county hospital. Her marriage had disintegrated years earlier. To cope with depression, she hid a daily ritual of orange juice and vodka from her children. She worked as a cashier, until nausea and fatigue overwhelmed her.

The first time I met her she sat on the gurney: petite, tanned, and pregnant. Then I saw her yellow eyes and revised: temporal wasting, jaundiced, and swollen with ascites. Rosa didn’t know that alcohol could cause liver disease. Without insurance or access to primary care, her untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression had snowballed for years.

Midway through my intern year, I’d taken care of many people with AUD. However, I’d barely learned anything about it as a medical student, though we’d spent weeks studying esoteric diseases, that now––9 years after medical school––I still have not encountered.

Among the 28.3 million individuals in the United States with AUD, only 1% receive medication treatment.1 In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use accounts for more than 95,000 deaths each year.2 This number likely under-captures alcohol-related mortality and is higher now given recent reports of increasing alcohol-related deaths and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, especially among women, younger age groups, and marginalized populations.3-5

Rosa had alcohol-related hepatitis, which can cause severe inflammation and liver failure and quickly lead to death. As her liver failure progressed, I asked the gastroenterologists, “What other treatments can we offer? Is she a liver transplant candidate?” “Nothing” and “No” they answered.

Later, I emailed the hepatologist and transplant surgeon begging them to reevaluate her transplantation candidacy, but they told me there was no exception to the institution’s 6-month sobriety rule.

Maintaining a 6-month sobriety period is not an evidence-based criterion for transplantation. However, 50% of transplant centers do not perform transplantation prior to 6 months of alcohol abstinence for alcohol-related hepatitis due to concern for return to drinking after transplant.6 This practice may promote bias in patient selection for transplantation. A recent study found that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease transplanted before 6 months of abstinence had similar rates of survival and return to drinking compared to those who abstained from alcohol for 6 months and participated in AUD treatment before transplantation.7

There are other liver transplant practices that result in inequities for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Some liver transplant centers consider being on a medication for opioid use disorder a contraindication for transplantation—even if the individual is in recovery and abstaining from substances.8 Others mandate that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings prior to transplant. While mutual help groups, including AA, may benefit some individuals, different approaches work for different people.9 Other psychosocial interventions (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and residential treatment) and medications also help individuals reduce or stop drinking. Some meet their goals without any treatment. Addiction care works best when it respects autonomy and meets individuals where they are by allowing them to decide among options.

While organ allocations are a crystalized example of inequities in addiction care, they are also ethically complex. Many individuals—with and without SUD—die on waiting lists and must meet stringent transplantation criteria. However, we can at least remove the unnecessary biases that compound inequities in care people with SUD already face.

As Rosa’s liver succumbed, her kidneys failed too, and she required dialysis. She sensed what was coming. “I want everything…for now. I need to take care of my children.” I, too, wanted Rosa to live and see her youngest start kindergarten.

A few days before her discharge, I walked to the pharmacy and bought a purple journal. In a rare moment, I found Rosa alone in her room, without her ex-husband, sister, and mother, who rarely left her bedside. Together, we called AA and explored whether she could start participating in phone meetings from the hospital. I explained that one way to document a commitment to sobriety, as the transplant center’s rules dictated, was to attend and document AA meetings in this notebook. “In 5 months, you will be a liver transplant candidate,” I remember saying, wishing it to fruition.

I became Rosa’s primary care physician and saw her in clinic. Over the next few weeks, her skin took on an ashen tone. Sleep escaped her and her thoughts and speech blurred. Her walk slowed and she needed a wheelchair. The quiet fierceness that had defined her dissipated as encephalopathy took over. But until our last visit, she brought her purple journal, tracking the AA meetings she’d attended. Dialysis became intolerable, but not before Rosa made care arrangements for her girls. When that happened, she stopped dialysis and went to Mexico, where she died in her sleep after saying good-bye to her father.

Earlier access to healthcare and effective depression and AUD treatment could have saved Rosa’s life. While it was too late for her, as hospitalists we care for many others with substance-related complications and may miss opportunities to discuss and offer evidence-based addiction treatment. For example, we initiate the most up-to-date management for a patient’s gastrointestinal bleed but may leave the alcohol discussion for someone else. It is similar for other SUD: we treat cellulitis, epidural abscesses, bacteremia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure exacerbations, and other complications of SUD without addressing the root cause of the hospitalization—other than to prescribe abstinence from substance use or, at our worst, scold individuals for continuing to use.

But what can we offer? Most healthcare professionals still do not receive addiction education during training. Without tools, we enact temporizing measures, until patients return to the hospital or die.

In addition to increasing alcohol-related morbidity, there have also been increases in drug-related overdoses, fueled by COVID-19, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and stimulants.10 In the 12-month period ending April 2021, more than 100,000 individuals died of drug-related overdoses, the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a year.11 Despite this, most healthcare systems remain unequipped to provide addiction services during hospitalization due to inadequate training, stigma, and lack of systems-based care.

Hospitalists and healthcare systems cannot be bystanders amid our worsening addiction crisis. We must empower clinicians with addiction education and ensure health systems offer evidence-based SUD services.

Educational efforts can close the knowledge gaps for both medical students and hospitalists. Medical schools should include foundational curricular content in screening, assessing, diagnosing, and treating SUD in alignment with standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which accredits US medical schools. Residency programs can offer educational conferences, cased-based discussions, and addiction medicine rotations. Hospitalists can participate in educational didactics and review evidence-based addiction guidelines.12,13 While the focus here is on hospitalists, clinicians across practice settings and specialties will encounter patients with SUD, and all need to be well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of addiction given the all-hands-on deck approach necessary amidst our worsening addiction crisis.

With one in nine hospitalizations involving individuals with SUD, and this number quickly rising, and with an annual cost to US hospitals of $13.2 billion, healthcare system leaders must invest in addiction care.14,15 Hospital-based addiction services could pay for themselves and save healthcare systems money while improving the patient and clinician experience.16One way to implement hospital-based addiction care is through an addiction consult team (ACT).17 While ACT compositions vary, most are interprofessional, offer evidence-based addiction treatment, and connect patients to community care.18 Our hospital’s ACT has nurses, patient navigators, and physicians who assess, diagnose, and treat SUD, and arrange follow-up addiction care.19 In addition to caring for individual patients, our ACT has led systems change. For example, we created order sets to guide clinicians, added medications to our hospital formulary to ensure access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and partnered with community stakeholders to streamline care transitions and access to psychosocial and medication treatment. Our team also worked with hospital leadership, nursing, and a syringe service program to integrate hospital harm reduction education and supply provision. Additionally, we are building capacity among staff, trainees, and clinicians through education and systems changes.

In hospitals without an ACT, leadership can finance SUD champions and integrate them into policy-level decision-making to implement best practices in addiction care and lead hospital-wide educational efforts. This will transform hospital culture and improve care as all clinicians develop essential addiction skills.

Addiction champions and ACTs could also advocate for equitable practices for patients with SUD to reduce the stigma that both prevents patients from seeking care and results in self-discharges.20 For example, with interprofessional support, we revised our in-hospital substance use policy. It previously entailed hospital security responding to substance use concerns, which unintentionally harmed patients and perpetuated stigma. Our revised policy ensures we offer medications for cravings and withdrawal, adequate pain management, and other services that address patients’ reasons for in-hospital substance use.

With the increasing prevalence of SUD among hospitalized patients, escalating substance-related deaths, rising healthcare costs, and the impact of addiction on health and well-being, addiction care, including ACTs and champions, must be adequately funded. However, sustainable financing remains a challenge.18

Caring for Rosa and others with SUD sparked my desire to learn about addiction, obtain addiction medicine board certification as a practicing hospitalist, and create an ACT that offers evidence-based addiction treatment. While much remains to be done, by collaborating with addiction champions and engaging hospital leadership, we have transformed our hospital’s approach to substance use care.

With the knowledge and resources I now have as an addiction medicine physician, I reimagine the possibilities for patients like Rosa.

Rosa died when living was possible.

*Name has been changed for patient privacy.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/data/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) application, 2013. Average for United States 2006–2010 alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/ARDI

3. Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451

4. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

5. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the covid-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942

6. Bangaru S, Pedersen MR, Macconmara MP, Singal AG, Mufti AR. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1357-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25285

7. Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1026-1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

8. Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(12):e13119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13119

9. Klimas J, Fairgrieve C, Tobin H, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009269.pub4

10. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

11. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

12. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

13. California Bridge Program. Tools: Treat substance use disorders from the acute care setting. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://cabridge.org/tools

14. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242

15. Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, et al. National prevalence of alcohol and other substance use disorders among emergency department visits and hospitalizations: NHAMCS 2014-2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;13:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w

16. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: Qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993

17. Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):822. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4

18. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496

19. Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(1):e001111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111

20. Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942

Rosa* was one of my first patients as an intern rotating at the county hospital. Her marriage had disintegrated years earlier. To cope with depression, she hid a daily ritual of orange juice and vodka from her children. She worked as a cashier, until nausea and fatigue overwhelmed her.

The first time I met her she sat on the gurney: petite, tanned, and pregnant. Then I saw her yellow eyes and revised: temporal wasting, jaundiced, and swollen with ascites. Rosa didn’t know that alcohol could cause liver disease. Without insurance or access to primary care, her untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression had snowballed for years.

Midway through my intern year, I’d taken care of many people with AUD. However, I’d barely learned anything about it as a medical student, though we’d spent weeks studying esoteric diseases, that now––9 years after medical school––I still have not encountered.

Among the 28.3 million individuals in the United States with AUD, only 1% receive medication treatment.1 In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use accounts for more than 95,000 deaths each year.2 This number likely under-captures alcohol-related mortality and is higher now given recent reports of increasing alcohol-related deaths and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, especially among women, younger age groups, and marginalized populations.3-5

Rosa had alcohol-related hepatitis, which can cause severe inflammation and liver failure and quickly lead to death. As her liver failure progressed, I asked the gastroenterologists, “What other treatments can we offer? Is she a liver transplant candidate?” “Nothing” and “No” they answered.

Later, I emailed the hepatologist and transplant surgeon begging them to reevaluate her transplantation candidacy, but they told me there was no exception to the institution’s 6-month sobriety rule.

Maintaining a 6-month sobriety period is not an evidence-based criterion for transplantation. However, 50% of transplant centers do not perform transplantation prior to 6 months of alcohol abstinence for alcohol-related hepatitis due to concern for return to drinking after transplant.6 This practice may promote bias in patient selection for transplantation. A recent study found that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease transplanted before 6 months of abstinence had similar rates of survival and return to drinking compared to those who abstained from alcohol for 6 months and participated in AUD treatment before transplantation.7

There are other liver transplant practices that result in inequities for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Some liver transplant centers consider being on a medication for opioid use disorder a contraindication for transplantation—even if the individual is in recovery and abstaining from substances.8 Others mandate that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings prior to transplant. While mutual help groups, including AA, may benefit some individuals, different approaches work for different people.9 Other psychosocial interventions (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and residential treatment) and medications also help individuals reduce or stop drinking. Some meet their goals without any treatment. Addiction care works best when it respects autonomy and meets individuals where they are by allowing them to decide among options.

While organ allocations are a crystalized example of inequities in addiction care, they are also ethically complex. Many individuals—with and without SUD—die on waiting lists and must meet stringent transplantation criteria. However, we can at least remove the unnecessary biases that compound inequities in care people with SUD already face.

As Rosa’s liver succumbed, her kidneys failed too, and she required dialysis. She sensed what was coming. “I want everything…for now. I need to take care of my children.” I, too, wanted Rosa to live and see her youngest start kindergarten.

A few days before her discharge, I walked to the pharmacy and bought a purple journal. In a rare moment, I found Rosa alone in her room, without her ex-husband, sister, and mother, who rarely left her bedside. Together, we called AA and explored whether she could start participating in phone meetings from the hospital. I explained that one way to document a commitment to sobriety, as the transplant center’s rules dictated, was to attend and document AA meetings in this notebook. “In 5 months, you will be a liver transplant candidate,” I remember saying, wishing it to fruition.

I became Rosa’s primary care physician and saw her in clinic. Over the next few weeks, her skin took on an ashen tone. Sleep escaped her and her thoughts and speech blurred. Her walk slowed and she needed a wheelchair. The quiet fierceness that had defined her dissipated as encephalopathy took over. But until our last visit, she brought her purple journal, tracking the AA meetings she’d attended. Dialysis became intolerable, but not before Rosa made care arrangements for her girls. When that happened, she stopped dialysis and went to Mexico, where she died in her sleep after saying good-bye to her father.

Earlier access to healthcare and effective depression and AUD treatment could have saved Rosa’s life. While it was too late for her, as hospitalists we care for many others with substance-related complications and may miss opportunities to discuss and offer evidence-based addiction treatment. For example, we initiate the most up-to-date management for a patient’s gastrointestinal bleed but may leave the alcohol discussion for someone else. It is similar for other SUD: we treat cellulitis, epidural abscesses, bacteremia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure exacerbations, and other complications of SUD without addressing the root cause of the hospitalization—other than to prescribe abstinence from substance use or, at our worst, scold individuals for continuing to use.

But what can we offer? Most healthcare professionals still do not receive addiction education during training. Without tools, we enact temporizing measures, until patients return to the hospital or die.

In addition to increasing alcohol-related morbidity, there have also been increases in drug-related overdoses, fueled by COVID-19, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and stimulants.10 In the 12-month period ending April 2021, more than 100,000 individuals died of drug-related overdoses, the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a year.11 Despite this, most healthcare systems remain unequipped to provide addiction services during hospitalization due to inadequate training, stigma, and lack of systems-based care.

Hospitalists and healthcare systems cannot be bystanders amid our worsening addiction crisis. We must empower clinicians with addiction education and ensure health systems offer evidence-based SUD services.

Educational efforts can close the knowledge gaps for both medical students and hospitalists. Medical schools should include foundational curricular content in screening, assessing, diagnosing, and treating SUD in alignment with standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which accredits US medical schools. Residency programs can offer educational conferences, cased-based discussions, and addiction medicine rotations. Hospitalists can participate in educational didactics and review evidence-based addiction guidelines.12,13 While the focus here is on hospitalists, clinicians across practice settings and specialties will encounter patients with SUD, and all need to be well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of addiction given the all-hands-on deck approach necessary amidst our worsening addiction crisis.

With one in nine hospitalizations involving individuals with SUD, and this number quickly rising, and with an annual cost to US hospitals of $13.2 billion, healthcare system leaders must invest in addiction care.14,15 Hospital-based addiction services could pay for themselves and save healthcare systems money while improving the patient and clinician experience.16One way to implement hospital-based addiction care is through an addiction consult team (ACT).17 While ACT compositions vary, most are interprofessional, offer evidence-based addiction treatment, and connect patients to community care.18 Our hospital’s ACT has nurses, patient navigators, and physicians who assess, diagnose, and treat SUD, and arrange follow-up addiction care.19 In addition to caring for individual patients, our ACT has led systems change. For example, we created order sets to guide clinicians, added medications to our hospital formulary to ensure access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and partnered with community stakeholders to streamline care transitions and access to psychosocial and medication treatment. Our team also worked with hospital leadership, nursing, and a syringe service program to integrate hospital harm reduction education and supply provision. Additionally, we are building capacity among staff, trainees, and clinicians through education and systems changes.

In hospitals without an ACT, leadership can finance SUD champions and integrate them into policy-level decision-making to implement best practices in addiction care and lead hospital-wide educational efforts. This will transform hospital culture and improve care as all clinicians develop essential addiction skills.

Addiction champions and ACTs could also advocate for equitable practices for patients with SUD to reduce the stigma that both prevents patients from seeking care and results in self-discharges.20 For example, with interprofessional support, we revised our in-hospital substance use policy. It previously entailed hospital security responding to substance use concerns, which unintentionally harmed patients and perpetuated stigma. Our revised policy ensures we offer medications for cravings and withdrawal, adequate pain management, and other services that address patients’ reasons for in-hospital substance use.

With the increasing prevalence of SUD among hospitalized patients, escalating substance-related deaths, rising healthcare costs, and the impact of addiction on health and well-being, addiction care, including ACTs and champions, must be adequately funded. However, sustainable financing remains a challenge.18

Caring for Rosa and others with SUD sparked my desire to learn about addiction, obtain addiction medicine board certification as a practicing hospitalist, and create an ACT that offers evidence-based addiction treatment. While much remains to be done, by collaborating with addiction champions and engaging hospital leadership, we have transformed our hospital’s approach to substance use care.

With the knowledge and resources I now have as an addiction medicine physician, I reimagine the possibilities for patients like Rosa.

Rosa died when living was possible.

*Name has been changed for patient privacy.

Rosa* was one of my first patients as an intern rotating at the county hospital. Her marriage had disintegrated years earlier. To cope with depression, she hid a daily ritual of orange juice and vodka from her children. She worked as a cashier, until nausea and fatigue overwhelmed her.

The first time I met her she sat on the gurney: petite, tanned, and pregnant. Then I saw her yellow eyes and revised: temporal wasting, jaundiced, and swollen with ascites. Rosa didn’t know that alcohol could cause liver disease. Without insurance or access to primary care, her untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression had snowballed for years.

Midway through my intern year, I’d taken care of many people with AUD. However, I’d barely learned anything about it as a medical student, though we’d spent weeks studying esoteric diseases, that now––9 years after medical school––I still have not encountered.

Among the 28.3 million individuals in the United States with AUD, only 1% receive medication treatment.1 In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use accounts for more than 95,000 deaths each year.2 This number likely under-captures alcohol-related mortality and is higher now given recent reports of increasing alcohol-related deaths and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, especially among women, younger age groups, and marginalized populations.3-5

Rosa had alcohol-related hepatitis, which can cause severe inflammation and liver failure and quickly lead to death. As her liver failure progressed, I asked the gastroenterologists, “What other treatments can we offer? Is she a liver transplant candidate?” “Nothing” and “No” they answered.

Later, I emailed the hepatologist and transplant surgeon begging them to reevaluate her transplantation candidacy, but they told me there was no exception to the institution’s 6-month sobriety rule.

Maintaining a 6-month sobriety period is not an evidence-based criterion for transplantation. However, 50% of transplant centers do not perform transplantation prior to 6 months of alcohol abstinence for alcohol-related hepatitis due to concern for return to drinking after transplant.6 This practice may promote bias in patient selection for transplantation. A recent study found that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease transplanted before 6 months of abstinence had similar rates of survival and return to drinking compared to those who abstained from alcohol for 6 months and participated in AUD treatment before transplantation.7

There are other liver transplant practices that result in inequities for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Some liver transplant centers consider being on a medication for opioid use disorder a contraindication for transplantation—even if the individual is in recovery and abstaining from substances.8 Others mandate that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings prior to transplant. While mutual help groups, including AA, may benefit some individuals, different approaches work for different people.9 Other psychosocial interventions (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and residential treatment) and medications also help individuals reduce or stop drinking. Some meet their goals without any treatment. Addiction care works best when it respects autonomy and meets individuals where they are by allowing them to decide among options.

While organ allocations are a crystalized example of inequities in addiction care, they are also ethically complex. Many individuals—with and without SUD—die on waiting lists and must meet stringent transplantation criteria. However, we can at least remove the unnecessary biases that compound inequities in care people with SUD already face.

As Rosa’s liver succumbed, her kidneys failed too, and she required dialysis. She sensed what was coming. “I want everything…for now. I need to take care of my children.” I, too, wanted Rosa to live and see her youngest start kindergarten.

A few days before her discharge, I walked to the pharmacy and bought a purple journal. In a rare moment, I found Rosa alone in her room, without her ex-husband, sister, and mother, who rarely left her bedside. Together, we called AA and explored whether she could start participating in phone meetings from the hospital. I explained that one way to document a commitment to sobriety, as the transplant center’s rules dictated, was to attend and document AA meetings in this notebook. “In 5 months, you will be a liver transplant candidate,” I remember saying, wishing it to fruition.

I became Rosa’s primary care physician and saw her in clinic. Over the next few weeks, her skin took on an ashen tone. Sleep escaped her and her thoughts and speech blurred. Her walk slowed and she needed a wheelchair. The quiet fierceness that had defined her dissipated as encephalopathy took over. But until our last visit, she brought her purple journal, tracking the AA meetings she’d attended. Dialysis became intolerable, but not before Rosa made care arrangements for her girls. When that happened, she stopped dialysis and went to Mexico, where she died in her sleep after saying good-bye to her father.

Earlier access to healthcare and effective depression and AUD treatment could have saved Rosa’s life. While it was too late for her, as hospitalists we care for many others with substance-related complications and may miss opportunities to discuss and offer evidence-based addiction treatment. For example, we initiate the most up-to-date management for a patient’s gastrointestinal bleed but may leave the alcohol discussion for someone else. It is similar for other SUD: we treat cellulitis, epidural abscesses, bacteremia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure exacerbations, and other complications of SUD without addressing the root cause of the hospitalization—other than to prescribe abstinence from substance use or, at our worst, scold individuals for continuing to use.

But what can we offer? Most healthcare professionals still do not receive addiction education during training. Without tools, we enact temporizing measures, until patients return to the hospital or die.

In addition to increasing alcohol-related morbidity, there have also been increases in drug-related overdoses, fueled by COVID-19, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and stimulants.10 In the 12-month period ending April 2021, more than 100,000 individuals died of drug-related overdoses, the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a year.11 Despite this, most healthcare systems remain unequipped to provide addiction services during hospitalization due to inadequate training, stigma, and lack of systems-based care.

Hospitalists and healthcare systems cannot be bystanders amid our worsening addiction crisis. We must empower clinicians with addiction education and ensure health systems offer evidence-based SUD services.

Educational efforts can close the knowledge gaps for both medical students and hospitalists. Medical schools should include foundational curricular content in screening, assessing, diagnosing, and treating SUD in alignment with standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which accredits US medical schools. Residency programs can offer educational conferences, cased-based discussions, and addiction medicine rotations. Hospitalists can participate in educational didactics and review evidence-based addiction guidelines.12,13 While the focus here is on hospitalists, clinicians across practice settings and specialties will encounter patients with SUD, and all need to be well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of addiction given the all-hands-on deck approach necessary amidst our worsening addiction crisis.

With one in nine hospitalizations involving individuals with SUD, and this number quickly rising, and with an annual cost to US hospitals of $13.2 billion, healthcare system leaders must invest in addiction care.14,15 Hospital-based addiction services could pay for themselves and save healthcare systems money while improving the patient and clinician experience.16One way to implement hospital-based addiction care is through an addiction consult team (ACT).17 While ACT compositions vary, most are interprofessional, offer evidence-based addiction treatment, and connect patients to community care.18 Our hospital’s ACT has nurses, patient navigators, and physicians who assess, diagnose, and treat SUD, and arrange follow-up addiction care.19 In addition to caring for individual patients, our ACT has led systems change. For example, we created order sets to guide clinicians, added medications to our hospital formulary to ensure access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and partnered with community stakeholders to streamline care transitions and access to psychosocial and medication treatment. Our team also worked with hospital leadership, nursing, and a syringe service program to integrate hospital harm reduction education and supply provision. Additionally, we are building capacity among staff, trainees, and clinicians through education and systems changes.

In hospitals without an ACT, leadership can finance SUD champions and integrate them into policy-level decision-making to implement best practices in addiction care and lead hospital-wide educational efforts. This will transform hospital culture and improve care as all clinicians develop essential addiction skills.

Addiction champions and ACTs could also advocate for equitable practices for patients with SUD to reduce the stigma that both prevents patients from seeking care and results in self-discharges.20 For example, with interprofessional support, we revised our in-hospital substance use policy. It previously entailed hospital security responding to substance use concerns, which unintentionally harmed patients and perpetuated stigma. Our revised policy ensures we offer medications for cravings and withdrawal, adequate pain management, and other services that address patients’ reasons for in-hospital substance use.

With the increasing prevalence of SUD among hospitalized patients, escalating substance-related deaths, rising healthcare costs, and the impact of addiction on health and well-being, addiction care, including ACTs and champions, must be adequately funded. However, sustainable financing remains a challenge.18

Caring for Rosa and others with SUD sparked my desire to learn about addiction, obtain addiction medicine board certification as a practicing hospitalist, and create an ACT that offers evidence-based addiction treatment. While much remains to be done, by collaborating with addiction champions and engaging hospital leadership, we have transformed our hospital’s approach to substance use care.

With the knowledge and resources I now have as an addiction medicine physician, I reimagine the possibilities for patients like Rosa.

Rosa died when living was possible.

*Name has been changed for patient privacy.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/data/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) application, 2013. Average for United States 2006–2010 alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/ARDI

3. Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451

4. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

5. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the covid-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942

6. Bangaru S, Pedersen MR, Macconmara MP, Singal AG, Mufti AR. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1357-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25285

7. Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1026-1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

8. Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(12):e13119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13119

9. Klimas J, Fairgrieve C, Tobin H, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009269.pub4

10. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

11. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

12. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

13. California Bridge Program. Tools: Treat substance use disorders from the acute care setting. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://cabridge.org/tools

14. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242

15. Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, et al. National prevalence of alcohol and other substance use disorders among emergency department visits and hospitalizations: NHAMCS 2014-2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;13:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w

16. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: Qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993

17. Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):822. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4

18. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496

19. Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(1):e001111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111

20. Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/data/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) application, 2013. Average for United States 2006–2010 alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/ARDI

3. Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451

4. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

5. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the covid-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942

6. Bangaru S, Pedersen MR, Macconmara MP, Singal AG, Mufti AR. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1357-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25285

7. Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1026-1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

8. Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(12):e13119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13119

9. Klimas J, Fairgrieve C, Tobin H, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009269.pub4

10. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

11. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

12. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

13. California Bridge Program. Tools: Treat substance use disorders from the acute care setting. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://cabridge.org/tools

14. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242

15. Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, et al. National prevalence of alcohol and other substance use disorders among emergency department visits and hospitalizations: NHAMCS 2014-2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;13:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w

16. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: Qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993

17. Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):822. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4

18. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496

19. Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(1):e001111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111

20. Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Kids Are Not Alright

“...but it all started to get worse during the pandemic.”

As the patient’s† door closed, I (JS) thought about what his father had shared: his 12-year-old son had experienced a slow decline in his mental health since March 2020. There had been a gradual loss of all the things his son needed for psychological well-being: school went virtual and extracurricular activities ceased, and with them went any sense of routine, normalcy, or authentic opportunities to socialize. His feelings of isolation and depression culminated in an attempt to end his own life. My mind shifted to other patients under our care: an 8-year-old with behavioral outbursts intensifying after school-based therapy ended, a 13-year-old who became suicidal from isolation and virtual bullying. These children’s families sought emergent care because they no longer had the resources to care for their children at home. My team left each of these rooms heartbroken, unsure of exactly what to say and aware of the limitations of our current healthcare system.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many pediatric providers have had similar experiences caring for countless patients who are “boarding”—awaiting transfer to a psychiatric facility for their primary acute psychiatric issue, initially in the emergency room, often for 5 days or more,1 then ultimately admitted to a general medical floor if an appropriate psychiatric bed is still not available.2 Unfortunately, just as parents have run out of resources to care for their children’s psychiatric needs, so too is our medical system lacking in resources to provide the acute care these children need in general hospitals.

This mental health crisis began before the COVID-19 pandemic3 but has only worsened in the wake of its resulting social isolation. During the pandemic, suicide hotlines had a 1000% increase in call volumes.4 COVID-19–induced bed closures simultaneously worsened an existing critical bed shortage5,6 and led to an increase in the average length of stay (LOS) for patients boarding in the emergency department (ED).7 In the state of Massachusetts, for example, psychiatric patients awaiting inpatient beds boarded for more than 10,000 hours in January 2021—more than ever before, and up approximately 4000 hours since January 2017.6 For pediatric patients, the average wait time is now 59 hours.6 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, 39% of children presenting to EDs for mental health complaints ended up boarding, which is an astounding figure and is unfortunately 7% higher than in 2019.8 Even these staggering numbers do not capture the full range of experiences, as many statistics do not account for time spent on inpatient units by patients who do not receive a bed placement after waiting hours to several days in the ED.

Shortages of space, as well as an underfunded and understaffed mental health workforce, lead to these prolonged, often traumatic boarding periods in hospitals designed to care for acute medical, rather than acute psychiatric, conditions. Patients awaiting psychiatric placement are waiting in settings that are chaotic, inconsistent, and lacking in privacy. A patient in the throes of psychosis or suicidality needs a therapeutic milieu, not one that interrupts their daily routine,2 disconnects them from their existing support networks, and is punctuated by the incessant clangs of bedside monitors and the hubbub of code teams. These environments are not therapeutic3 for young infants with fevers, let alone for teenagers battling suicidality and eating disorders. In fact, for these reasons, we suspect that many of our patients’ inpatient ”behavioral escalations” are in fact triggered by their hospital environment, which may contribute to the 300% increase in the number of pharmacological restraints used during mental health visits in the ED over the past 10 years.9

None of us imagined when we chose to pursue pediatrics a that significant—and at times predominant—portion of our training would encompass caring for patients with acute mental health concerns. And although we did not anticipate this crisis, we have now been tasked with managing it. Throughout the day, when we are called to see our patients with primarily psychiatric pathology, we are often at war with ourselves. We weigh forming deeply meaningful relationships with these patients against the potential of unintentionally retraumatizing them or forming bonds that will be abruptly severed when patients are transferred to a psychiatric facility, which often occurs with barely a few hours’ notice. Moreover, many healthcare workers have training ill-suited to meet the needs of these patients. Just as emergency physicians can diagnose appendicitis but rely on surgeons to provide timely surgical treatment, general pediatricians identify psychiatric crises but rely on psychiatrists for ideal treatment plans. And almost daily, we are called to an “escalating” patient and arrive minutes into a stressful situation that others expect us to extinguish expeditiously. Along with nursing colleagues and the behavioral response team, we enact the treatment plan laid out by our psychiatry colleagues and wonder whether there is a better way.

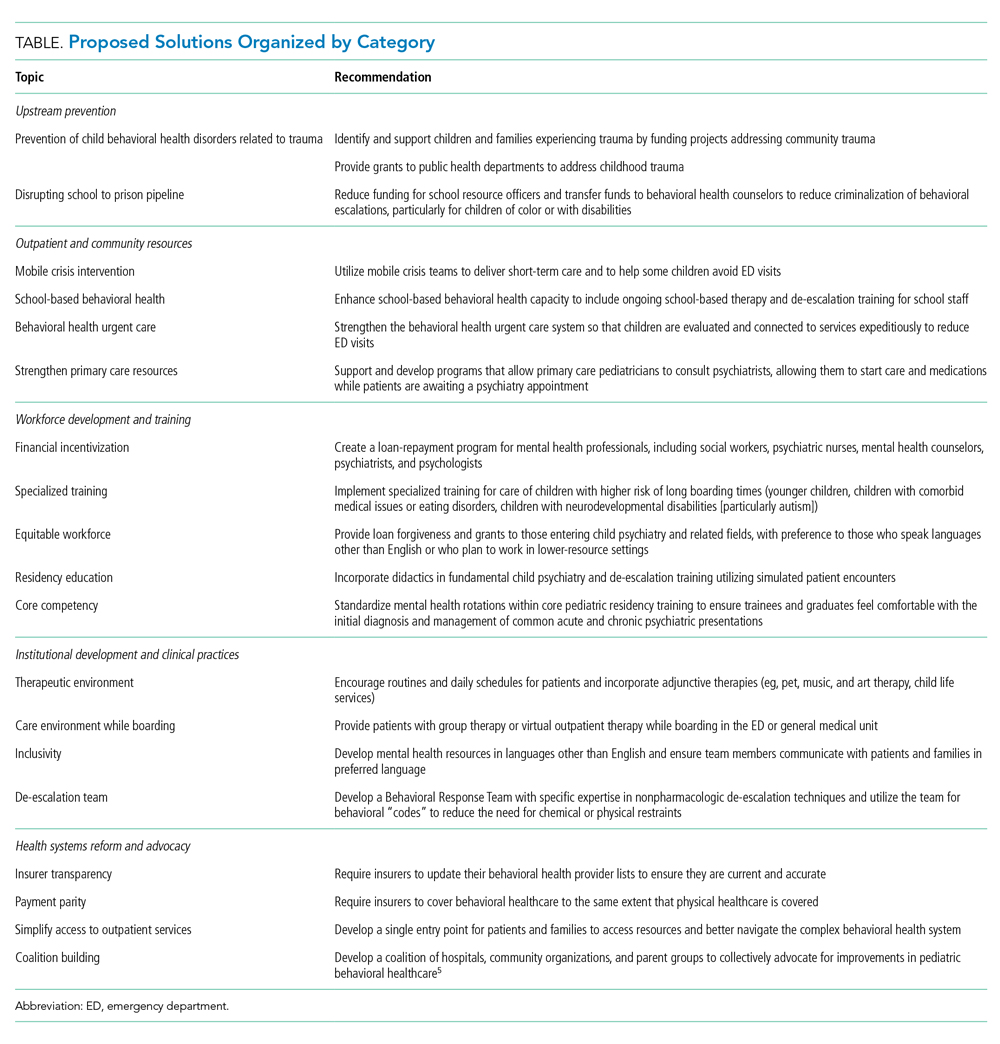

We propose the following changes to create a more ideal health system (Table). We acknowledge that each health system has unique resources, challenges, and patient populations. Thus, our recommendations are not comprehensive and are largely based on experiences within our own institutions and state, but they encompass many domains that impact and are affected by child and adolescent mental healthcare in the United States, ranging from program- and hospital-level innovation to community and legislative action.

UPSTREAM PREVENTION

Like all good health system designs, we recommend prioritizing prevention. This would entail funding programs and legislation such as H.R. 3180, the RISE from Trauma Act, and H.R. 8544, the STRONG Support for Children Act of 2020 (both currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives) that support early childhood development and prevent adverse childhood experiences and trauma, averting mental health diagnoses such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder before they begin.10

OUTPATIENT AND COMMUNITY RESOURCES

We recognize that schools and general pediatricians have far more exposure to children at risk for mental health crises than do subspecialists. Thus, we urge an equitable increase in access to mental healthcare in the community so that patients needing assistance are screened and diagnosed earlier in their illness, allowing for secondary prevention of worsening mental health disorders. We support increased funding for programs such as the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, which allows primary care doctors to consult psychiatrists in real time, closing the gap between a primary care visit and specialty follow-up. Telehealth services will be key to improving access for patients themselves and to allow pediatricians to consult with mental health professionals to initiate care prior to specialist availability. We envision that strengthening school-based behavioral health resources will also help prevent ED visits. Behavioral healthcare should be integrated into schools and community centers while police presence is simultaneously reduced, as there is evidence of an increased likelihood of juvenile justice involvement for children with disabilities and mental health needs.11,12

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT AND TRAINING

Ensuring access necessitates increasing the capacity of our psychiatric workforce by encouraging graduates to pursue mental health occupations with concrete financial incentives such as loan repayment and training grants. We thus support legislation such as H.R. 6597, the Mental Health Professionals Workforce Shortage Loan Repayment Act of 2018 (currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives). This may also improve recruitment and retention of individuals who are underrepresented in medicine, one step in helping ensure children have access to linguistically appropriate and culturally sensitive care. Residency programs and hospital systems should expand their training and education to identify and stabilize patients in mental health in extremis through culturally sensitive curricula focused on behavioral de-escalation techniques, trauma-informed care, and psychopharmacology. Our own residency program created a 2-week mental health rotation13 that includes rotating with outpatient mental health providers and our hospital’s behavioral response team, a group of trauma-informed responders for behavioral emergencies. Similar training should be available for nursing and other allied health professionals, who are often the first responders to behavioral escalations.13

INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND CLINICAL PRACTICES

Ideally, patients requiring higher-intensity psychiatric care would be referred to specialized pediatric behavioral health urgent care centers so their conditions can be adequately evaluated and addressed by staff trained in psychiatric management and in therapeutic environments. We believe all providers caring for children with mental health needs should be trained in basic, but core, behavioral health and de-escalation competencies, including specialized training for children with comorbid medical and neurodevelopmental diagnoses, such as autism. These centers should have specific beds for young children and those with developmental or complex care needs, and services should be available in numerous languages and levels of health literacy to allow all families to participate in their child’s care. At the same time, even nonpsychiatric EDs and inpatient units should commit resources to developing a maximally therapeutic environment, including allowing adjunctive services such as child life services, group therapy, and pet and music therapy, and create environments that support, rather than disrupt, normal routines.

HEALTH SYSTEMS REFORM AND ADVOCACY

Underpinning all the above innovations are changes to our healthcare payment system and provider networks, including the need for insurance coverage and payment parity for behavioral health, to ensure care is not only accessible but affordable. Additionally, for durable change, we need more than just education—we need coalition building and advocacy. Many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have begun this work, which we must all continue.14 Bringing in diverse partners, including health systems, providers, educators, hospital administrators, payors, elected officials, and communities, will prioritize children’s needs and create a more ideal pediatric behavioral healthcare system.15

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire need for comprehensive mental healthcare in the United States, a need that existed before the pandemic and will persist in a more fragile state long after it ends. Our hope is that the pandemic serves as the catalyst necessary to promote the magnitude of investments and stakeholder buy-in necessary to improve pediatric mental health and engender a radical redesign of our behavioral healthcare system. Our patients are counting on us to act. Together, we can build a system that ensures that the kids will be alright.

†Patient details have been changed for patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Perdomo, MD, Amara Azubuike, JD, and Josh Greenberg, JD, for reading and providing feedback on earlier versions of this work.

1. “This is a crisis”: mom whose son has boarded 33 days for psych bed calls for state action. WBUR News. Updated March 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/26/mental-health-boarding-hospitals

2. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813-824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

3. Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005-2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-030692

4. Cloutier RL, Marshaall R. A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:776-777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008

5. Schoenberg S. Lack of mental health beds means long ER waits. CommonWealth Magazine. April 15, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://commonwealthmagazine.org/health-care/lack-of-mental-health-beds-means-long-er-waits/

6. Jolicoeur L, Mullins L. Mass. physicians call on state to address ER “boarding” of patients awaiting admission. WBUR News. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/02/emergency-department-er-inpatient-beds-boarding

7. Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533

8. Impact of COVID-19 on the Massachusetts Health Care System: Interim Report. Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. April 2021. Accessed September 25, 2021. www.mass.gov/doc/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-massachusetts-health-care-system-interim-report/download

9. Foster AA, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Hoffmann JA, Hudgins JD. Pharmacologic restraint use during mental health visits in pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2021;236:276-283.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.027

10. Brown NM, Brown SN, Briggs RD, Germán M, Belamarich PF, Oyeku SO. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):349-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013

11. Harper K, Ryberg R, Temkin D. Black students and students with disabilities remain more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions, despite overall declines. Child Trends. April 29, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.childtrends.org/publications/black-students-disabilities-out-of-school-suspensions

12. Whitaker A, Torres-Guillén S, Morton M, et al. Cops and no counselors: how the lack of school mental health staff is harming students. American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed August 6, 2021. www.aclu.org/report/cops-and-no-counselors

13. Education. Boston Combined Residence Program. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://msbcrp.wpengine.com/program/education/

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Interim guidance on supporting the emotional and behavioral health needs of children, adolescents, and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated July 28, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. http://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/interim-guidance-on-supporting-the-emotional-and-behavioral-health-needs-of-children-adolescents-and-families-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

15. Advocacy. Children’s Mental Health Campaign. Accessed August 4, 2021. https://childrensmentalhealthcampaign.org/advocacy

“...but it all started to get worse during the pandemic.”

As the patient’s† door closed, I (JS) thought about what his father had shared: his 12-year-old son had experienced a slow decline in his mental health since March 2020. There had been a gradual loss of all the things his son needed for psychological well-being: school went virtual and extracurricular activities ceased, and with them went any sense of routine, normalcy, or authentic opportunities to socialize. His feelings of isolation and depression culminated in an attempt to end his own life. My mind shifted to other patients under our care: an 8-year-old with behavioral outbursts intensifying after school-based therapy ended, a 13-year-old who became suicidal from isolation and virtual bullying. These children’s families sought emergent care because they no longer had the resources to care for their children at home. My team left each of these rooms heartbroken, unsure of exactly what to say and aware of the limitations of our current healthcare system.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many pediatric providers have had similar experiences caring for countless patients who are “boarding”—awaiting transfer to a psychiatric facility for their primary acute psychiatric issue, initially in the emergency room, often for 5 days or more,1 then ultimately admitted to a general medical floor if an appropriate psychiatric bed is still not available.2 Unfortunately, just as parents have run out of resources to care for their children’s psychiatric needs, so too is our medical system lacking in resources to provide the acute care these children need in general hospitals.

This mental health crisis began before the COVID-19 pandemic3 but has only worsened in the wake of its resulting social isolation. During the pandemic, suicide hotlines had a 1000% increase in call volumes.4 COVID-19–induced bed closures simultaneously worsened an existing critical bed shortage5,6 and led to an increase in the average length of stay (LOS) for patients boarding in the emergency department (ED).7 In the state of Massachusetts, for example, psychiatric patients awaiting inpatient beds boarded for more than 10,000 hours in January 2021—more than ever before, and up approximately 4000 hours since January 2017.6 For pediatric patients, the average wait time is now 59 hours.6 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, 39% of children presenting to EDs for mental health complaints ended up boarding, which is an astounding figure and is unfortunately 7% higher than in 2019.8 Even these staggering numbers do not capture the full range of experiences, as many statistics do not account for time spent on inpatient units by patients who do not receive a bed placement after waiting hours to several days in the ED.

Shortages of space, as well as an underfunded and understaffed mental health workforce, lead to these prolonged, often traumatic boarding periods in hospitals designed to care for acute medical, rather than acute psychiatric, conditions. Patients awaiting psychiatric placement are waiting in settings that are chaotic, inconsistent, and lacking in privacy. A patient in the throes of psychosis or suicidality needs a therapeutic milieu, not one that interrupts their daily routine,2 disconnects them from their existing support networks, and is punctuated by the incessant clangs of bedside monitors and the hubbub of code teams. These environments are not therapeutic3 for young infants with fevers, let alone for teenagers battling suicidality and eating disorders. In fact, for these reasons, we suspect that many of our patients’ inpatient ”behavioral escalations” are in fact triggered by their hospital environment, which may contribute to the 300% increase in the number of pharmacological restraints used during mental health visits in the ED over the past 10 years.9

None of us imagined when we chose to pursue pediatrics a that significant—and at times predominant—portion of our training would encompass caring for patients with acute mental health concerns. And although we did not anticipate this crisis, we have now been tasked with managing it. Throughout the day, when we are called to see our patients with primarily psychiatric pathology, we are often at war with ourselves. We weigh forming deeply meaningful relationships with these patients against the potential of unintentionally retraumatizing them or forming bonds that will be abruptly severed when patients are transferred to a psychiatric facility, which often occurs with barely a few hours’ notice. Moreover, many healthcare workers have training ill-suited to meet the needs of these patients. Just as emergency physicians can diagnose appendicitis but rely on surgeons to provide timely surgical treatment, general pediatricians identify psychiatric crises but rely on psychiatrists for ideal treatment plans. And almost daily, we are called to an “escalating” patient and arrive minutes into a stressful situation that others expect us to extinguish expeditiously. Along with nursing colleagues and the behavioral response team, we enact the treatment plan laid out by our psychiatry colleagues and wonder whether there is a better way.

We propose the following changes to create a more ideal health system (Table). We acknowledge that each health system has unique resources, challenges, and patient populations. Thus, our recommendations are not comprehensive and are largely based on experiences within our own institutions and state, but they encompass many domains that impact and are affected by child and adolescent mental healthcare in the United States, ranging from program- and hospital-level innovation to community and legislative action.

UPSTREAM PREVENTION

Like all good health system designs, we recommend prioritizing prevention. This would entail funding programs and legislation such as H.R. 3180, the RISE from Trauma Act, and H.R. 8544, the STRONG Support for Children Act of 2020 (both currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives) that support early childhood development and prevent adverse childhood experiences and trauma, averting mental health diagnoses such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder before they begin.10

OUTPATIENT AND COMMUNITY RESOURCES

We recognize that schools and general pediatricians have far more exposure to children at risk for mental health crises than do subspecialists. Thus, we urge an equitable increase in access to mental healthcare in the community so that patients needing assistance are screened and diagnosed earlier in their illness, allowing for secondary prevention of worsening mental health disorders. We support increased funding for programs such as the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, which allows primary care doctors to consult psychiatrists in real time, closing the gap between a primary care visit and specialty follow-up. Telehealth services will be key to improving access for patients themselves and to allow pediatricians to consult with mental health professionals to initiate care prior to specialist availability. We envision that strengthening school-based behavioral health resources will also help prevent ED visits. Behavioral healthcare should be integrated into schools and community centers while police presence is simultaneously reduced, as there is evidence of an increased likelihood of juvenile justice involvement for children with disabilities and mental health needs.11,12

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT AND TRAINING

Ensuring access necessitates increasing the capacity of our psychiatric workforce by encouraging graduates to pursue mental health occupations with concrete financial incentives such as loan repayment and training grants. We thus support legislation such as H.R. 6597, the Mental Health Professionals Workforce Shortage Loan Repayment Act of 2018 (currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives). This may also improve recruitment and retention of individuals who are underrepresented in medicine, one step in helping ensure children have access to linguistically appropriate and culturally sensitive care. Residency programs and hospital systems should expand their training and education to identify and stabilize patients in mental health in extremis through culturally sensitive curricula focused on behavioral de-escalation techniques, trauma-informed care, and psychopharmacology. Our own residency program created a 2-week mental health rotation13 that includes rotating with outpatient mental health providers and our hospital’s behavioral response team, a group of trauma-informed responders for behavioral emergencies. Similar training should be available for nursing and other allied health professionals, who are often the first responders to behavioral escalations.13

INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND CLINICAL PRACTICES

Ideally, patients requiring higher-intensity psychiatric care would be referred to specialized pediatric behavioral health urgent care centers so their conditions can be adequately evaluated and addressed by staff trained in psychiatric management and in therapeutic environments. We believe all providers caring for children with mental health needs should be trained in basic, but core, behavioral health and de-escalation competencies, including specialized training for children with comorbid medical and neurodevelopmental diagnoses, such as autism. These centers should have specific beds for young children and those with developmental or complex care needs, and services should be available in numerous languages and levels of health literacy to allow all families to participate in their child’s care. At the same time, even nonpsychiatric EDs and inpatient units should commit resources to developing a maximally therapeutic environment, including allowing adjunctive services such as child life services, group therapy, and pet and music therapy, and create environments that support, rather than disrupt, normal routines.

HEALTH SYSTEMS REFORM AND ADVOCACY

Underpinning all the above innovations are changes to our healthcare payment system and provider networks, including the need for insurance coverage and payment parity for behavioral health, to ensure care is not only accessible but affordable. Additionally, for durable change, we need more than just education—we need coalition building and advocacy. Many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have begun this work, which we must all continue.14 Bringing in diverse partners, including health systems, providers, educators, hospital administrators, payors, elected officials, and communities, will prioritize children’s needs and create a more ideal pediatric behavioral healthcare system.15

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire need for comprehensive mental healthcare in the United States, a need that existed before the pandemic and will persist in a more fragile state long after it ends. Our hope is that the pandemic serves as the catalyst necessary to promote the magnitude of investments and stakeholder buy-in necessary to improve pediatric mental health and engender a radical redesign of our behavioral healthcare system. Our patients are counting on us to act. Together, we can build a system that ensures that the kids will be alright.

†Patient details have been changed for patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Perdomo, MD, Amara Azubuike, JD, and Josh Greenberg, JD, for reading and providing feedback on earlier versions of this work.

“...but it all started to get worse during the pandemic.”

As the patient’s† door closed, I (JS) thought about what his father had shared: his 12-year-old son had experienced a slow decline in his mental health since March 2020. There had been a gradual loss of all the things his son needed for psychological well-being: school went virtual and extracurricular activities ceased, and with them went any sense of routine, normalcy, or authentic opportunities to socialize. His feelings of isolation and depression culminated in an attempt to end his own life. My mind shifted to other patients under our care: an 8-year-old with behavioral outbursts intensifying after school-based therapy ended, a 13-year-old who became suicidal from isolation and virtual bullying. These children’s families sought emergent care because they no longer had the resources to care for their children at home. My team left each of these rooms heartbroken, unsure of exactly what to say and aware of the limitations of our current healthcare system.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many pediatric providers have had similar experiences caring for countless patients who are “boarding”—awaiting transfer to a psychiatric facility for their primary acute psychiatric issue, initially in the emergency room, often for 5 days or more,1 then ultimately admitted to a general medical floor if an appropriate psychiatric bed is still not available.2 Unfortunately, just as parents have run out of resources to care for their children’s psychiatric needs, so too is our medical system lacking in resources to provide the acute care these children need in general hospitals.

This mental health crisis began before the COVID-19 pandemic3 but has only worsened in the wake of its resulting social isolation. During the pandemic, suicide hotlines had a 1000% increase in call volumes.4 COVID-19–induced bed closures simultaneously worsened an existing critical bed shortage5,6 and led to an increase in the average length of stay (LOS) for patients boarding in the emergency department (ED).7 In the state of Massachusetts, for example, psychiatric patients awaiting inpatient beds boarded for more than 10,000 hours in January 2021—more than ever before, and up approximately 4000 hours since January 2017.6 For pediatric patients, the average wait time is now 59 hours.6 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, 39% of children presenting to EDs for mental health complaints ended up boarding, which is an astounding figure and is unfortunately 7% higher than in 2019.8 Even these staggering numbers do not capture the full range of experiences, as many statistics do not account for time spent on inpatient units by patients who do not receive a bed placement after waiting hours to several days in the ED.

Shortages of space, as well as an underfunded and understaffed mental health workforce, lead to these prolonged, often traumatic boarding periods in hospitals designed to care for acute medical, rather than acute psychiatric, conditions. Patients awaiting psychiatric placement are waiting in settings that are chaotic, inconsistent, and lacking in privacy. A patient in the throes of psychosis or suicidality needs a therapeutic milieu, not one that interrupts their daily routine,2 disconnects them from their existing support networks, and is punctuated by the incessant clangs of bedside monitors and the hubbub of code teams. These environments are not therapeutic3 for young infants with fevers, let alone for teenagers battling suicidality and eating disorders. In fact, for these reasons, we suspect that many of our patients’ inpatient ”behavioral escalations” are in fact triggered by their hospital environment, which may contribute to the 300% increase in the number of pharmacological restraints used during mental health visits in the ED over the past 10 years.9