User login

Beyond a Purple Journal: Improving Hospital-Based Addiction Care

Rosa* was one of my first patients as an intern rotating at the county hospital. Her marriage had disintegrated years earlier. To cope with depression, she hid a daily ritual of orange juice and vodka from her children. She worked as a cashier, until nausea and fatigue overwhelmed her.

The first time I met her she sat on the gurney: petite, tanned, and pregnant. Then I saw her yellow eyes and revised: temporal wasting, jaundiced, and swollen with ascites. Rosa didn’t know that alcohol could cause liver disease. Without insurance or access to primary care, her untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression had snowballed for years.

Midway through my intern year, I’d taken care of many people with AUD. However, I’d barely learned anything about it as a medical student, though we’d spent weeks studying esoteric diseases, that now––9 years after medical school––I still have not encountered.

Among the 28.3 million individuals in the United States with AUD, only 1% receive medication treatment.1 In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use accounts for more than 95,000 deaths each year.2 This number likely under-captures alcohol-related mortality and is higher now given recent reports of increasing alcohol-related deaths and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, especially among women, younger age groups, and marginalized populations.3-5

Rosa had alcohol-related hepatitis, which can cause severe inflammation and liver failure and quickly lead to death. As her liver failure progressed, I asked the gastroenterologists, “What other treatments can we offer? Is she a liver transplant candidate?” “Nothing” and “No” they answered.

Later, I emailed the hepatologist and transplant surgeon begging them to reevaluate her transplantation candidacy, but they told me there was no exception to the institution’s 6-month sobriety rule.

Maintaining a 6-month sobriety period is not an evidence-based criterion for transplantation. However, 50% of transplant centers do not perform transplantation prior to 6 months of alcohol abstinence for alcohol-related hepatitis due to concern for return to drinking after transplant.6 This practice may promote bias in patient selection for transplantation. A recent study found that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease transplanted before 6 months of abstinence had similar rates of survival and return to drinking compared to those who abstained from alcohol for 6 months and participated in AUD treatment before transplantation.7

There are other liver transplant practices that result in inequities for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Some liver transplant centers consider being on a medication for opioid use disorder a contraindication for transplantation—even if the individual is in recovery and abstaining from substances.8 Others mandate that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings prior to transplant. While mutual help groups, including AA, may benefit some individuals, different approaches work for different people.9 Other psychosocial interventions (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and residential treatment) and medications also help individuals reduce or stop drinking. Some meet their goals without any treatment. Addiction care works best when it respects autonomy and meets individuals where they are by allowing them to decide among options.

While organ allocations are a crystalized example of inequities in addiction care, they are also ethically complex. Many individuals—with and without SUD—die on waiting lists and must meet stringent transplantation criteria. However, we can at least remove the unnecessary biases that compound inequities in care people with SUD already face.

As Rosa’s liver succumbed, her kidneys failed too, and she required dialysis. She sensed what was coming. “I want everything…for now. I need to take care of my children.” I, too, wanted Rosa to live and see her youngest start kindergarten.

A few days before her discharge, I walked to the pharmacy and bought a purple journal. In a rare moment, I found Rosa alone in her room, without her ex-husband, sister, and mother, who rarely left her bedside. Together, we called AA and explored whether she could start participating in phone meetings from the hospital. I explained that one way to document a commitment to sobriety, as the transplant center’s rules dictated, was to attend and document AA meetings in this notebook. “In 5 months, you will be a liver transplant candidate,” I remember saying, wishing it to fruition.

I became Rosa’s primary care physician and saw her in clinic. Over the next few weeks, her skin took on an ashen tone. Sleep escaped her and her thoughts and speech blurred. Her walk slowed and she needed a wheelchair. The quiet fierceness that had defined her dissipated as encephalopathy took over. But until our last visit, she brought her purple journal, tracking the AA meetings she’d attended. Dialysis became intolerable, but not before Rosa made care arrangements for her girls. When that happened, she stopped dialysis and went to Mexico, where she died in her sleep after saying good-bye to her father.

Earlier access to healthcare and effective depression and AUD treatment could have saved Rosa’s life. While it was too late for her, as hospitalists we care for many others with substance-related complications and may miss opportunities to discuss and offer evidence-based addiction treatment. For example, we initiate the most up-to-date management for a patient’s gastrointestinal bleed but may leave the alcohol discussion for someone else. It is similar for other SUD: we treat cellulitis, epidural abscesses, bacteremia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure exacerbations, and other complications of SUD without addressing the root cause of the hospitalization—other than to prescribe abstinence from substance use or, at our worst, scold individuals for continuing to use.

But what can we offer? Most healthcare professionals still do not receive addiction education during training. Without tools, we enact temporizing measures, until patients return to the hospital or die.

In addition to increasing alcohol-related morbidity, there have also been increases in drug-related overdoses, fueled by COVID-19, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and stimulants.10 In the 12-month period ending April 2021, more than 100,000 individuals died of drug-related overdoses, the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a year.11 Despite this, most healthcare systems remain unequipped to provide addiction services during hospitalization due to inadequate training, stigma, and lack of systems-based care.

Hospitalists and healthcare systems cannot be bystanders amid our worsening addiction crisis. We must empower clinicians with addiction education and ensure health systems offer evidence-based SUD services.

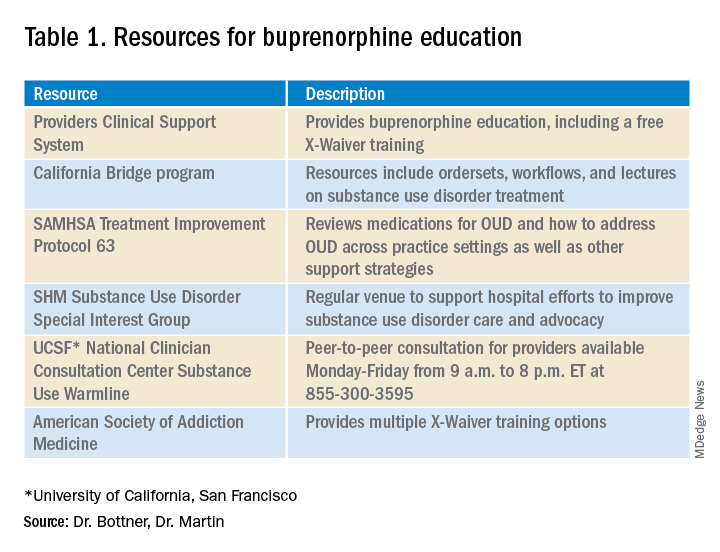

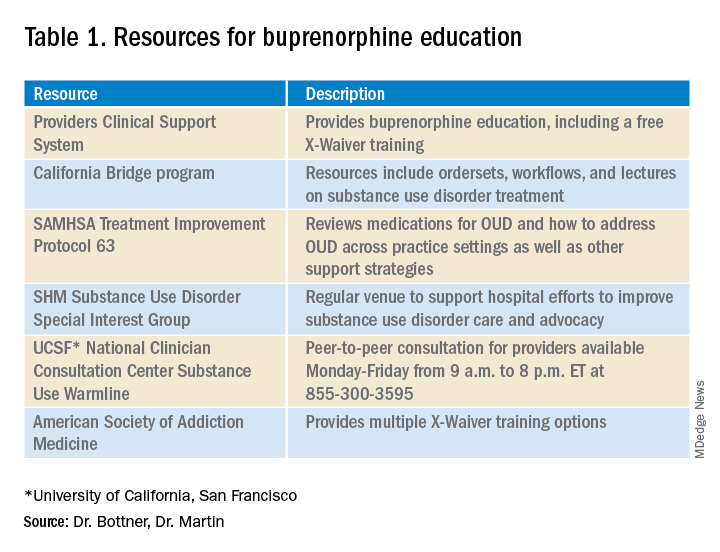

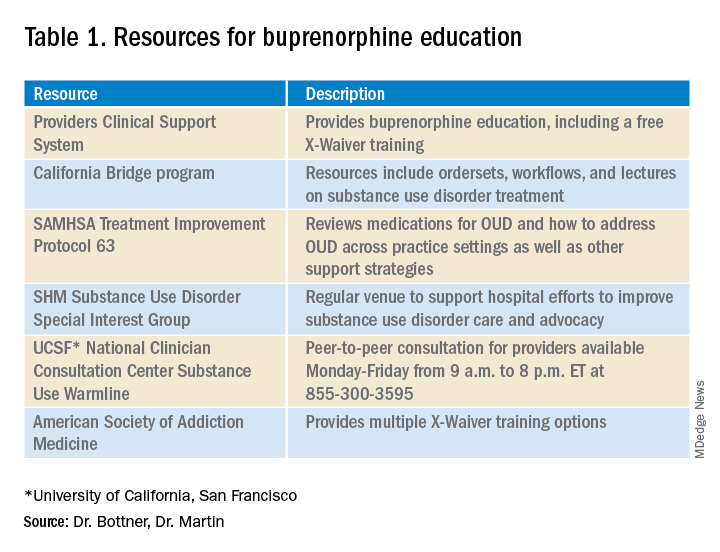

Educational efforts can close the knowledge gaps for both medical students and hospitalists. Medical schools should include foundational curricular content in screening, assessing, diagnosing, and treating SUD in alignment with standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which accredits US medical schools. Residency programs can offer educational conferences, cased-based discussions, and addiction medicine rotations. Hospitalists can participate in educational didactics and review evidence-based addiction guidelines.12,13 While the focus here is on hospitalists, clinicians across practice settings and specialties will encounter patients with SUD, and all need to be well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of addiction given the all-hands-on deck approach necessary amidst our worsening addiction crisis.

With one in nine hospitalizations involving individuals with SUD, and this number quickly rising, and with an annual cost to US hospitals of $13.2 billion, healthcare system leaders must invest in addiction care.14,15 Hospital-based addiction services could pay for themselves and save healthcare systems money while improving the patient and clinician experience.16One way to implement hospital-based addiction care is through an addiction consult team (ACT).17 While ACT compositions vary, most are interprofessional, offer evidence-based addiction treatment, and connect patients to community care.18 Our hospital’s ACT has nurses, patient navigators, and physicians who assess, diagnose, and treat SUD, and arrange follow-up addiction care.19 In addition to caring for individual patients, our ACT has led systems change. For example, we created order sets to guide clinicians, added medications to our hospital formulary to ensure access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and partnered with community stakeholders to streamline care transitions and access to psychosocial and medication treatment. Our team also worked with hospital leadership, nursing, and a syringe service program to integrate hospital harm reduction education and supply provision. Additionally, we are building capacity among staff, trainees, and clinicians through education and systems changes.

In hospitals without an ACT, leadership can finance SUD champions and integrate them into policy-level decision-making to implement best practices in addiction care and lead hospital-wide educational efforts. This will transform hospital culture and improve care as all clinicians develop essential addiction skills.

Addiction champions and ACTs could also advocate for equitable practices for patients with SUD to reduce the stigma that both prevents patients from seeking care and results in self-discharges.20 For example, with interprofessional support, we revised our in-hospital substance use policy. It previously entailed hospital security responding to substance use concerns, which unintentionally harmed patients and perpetuated stigma. Our revised policy ensures we offer medications for cravings and withdrawal, adequate pain management, and other services that address patients’ reasons for in-hospital substance use.

With the increasing prevalence of SUD among hospitalized patients, escalating substance-related deaths, rising healthcare costs, and the impact of addiction on health and well-being, addiction care, including ACTs and champions, must be adequately funded. However, sustainable financing remains a challenge.18

Caring for Rosa and others with SUD sparked my desire to learn about addiction, obtain addiction medicine board certification as a practicing hospitalist, and create an ACT that offers evidence-based addiction treatment. While much remains to be done, by collaborating with addiction champions and engaging hospital leadership, we have transformed our hospital’s approach to substance use care.

With the knowledge and resources I now have as an addiction medicine physician, I reimagine the possibilities for patients like Rosa.

Rosa died when living was possible.

*Name has been changed for patient privacy.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/data/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) application, 2013. Average for United States 2006–2010 alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/ARDI

3. Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451

4. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

5. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the covid-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942

6. Bangaru S, Pedersen MR, Macconmara MP, Singal AG, Mufti AR. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1357-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25285

7. Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1026-1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

8. Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(12):e13119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13119

9. Klimas J, Fairgrieve C, Tobin H, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009269.pub4

10. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

11. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

12. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

13. California Bridge Program. Tools: Treat substance use disorders from the acute care setting. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://cabridge.org/tools

14. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242

15. Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, et al. National prevalence of alcohol and other substance use disorders among emergency department visits and hospitalizations: NHAMCS 2014-2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;13:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w

16. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: Qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993

17. Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):822. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4

18. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496

19. Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(1):e001111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111

20. Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942

Rosa* was one of my first patients as an intern rotating at the county hospital. Her marriage had disintegrated years earlier. To cope with depression, she hid a daily ritual of orange juice and vodka from her children. She worked as a cashier, until nausea and fatigue overwhelmed her.

The first time I met her she sat on the gurney: petite, tanned, and pregnant. Then I saw her yellow eyes and revised: temporal wasting, jaundiced, and swollen with ascites. Rosa didn’t know that alcohol could cause liver disease. Without insurance or access to primary care, her untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression had snowballed for years.

Midway through my intern year, I’d taken care of many people with AUD. However, I’d barely learned anything about it as a medical student, though we’d spent weeks studying esoteric diseases, that now––9 years after medical school––I still have not encountered.

Among the 28.3 million individuals in the United States with AUD, only 1% receive medication treatment.1 In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use accounts for more than 95,000 deaths each year.2 This number likely under-captures alcohol-related mortality and is higher now given recent reports of increasing alcohol-related deaths and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, especially among women, younger age groups, and marginalized populations.3-5

Rosa had alcohol-related hepatitis, which can cause severe inflammation and liver failure and quickly lead to death. As her liver failure progressed, I asked the gastroenterologists, “What other treatments can we offer? Is she a liver transplant candidate?” “Nothing” and “No” they answered.

Later, I emailed the hepatologist and transplant surgeon begging them to reevaluate her transplantation candidacy, but they told me there was no exception to the institution’s 6-month sobriety rule.

Maintaining a 6-month sobriety period is not an evidence-based criterion for transplantation. However, 50% of transplant centers do not perform transplantation prior to 6 months of alcohol abstinence for alcohol-related hepatitis due to concern for return to drinking after transplant.6 This practice may promote bias in patient selection for transplantation. A recent study found that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease transplanted before 6 months of abstinence had similar rates of survival and return to drinking compared to those who abstained from alcohol for 6 months and participated in AUD treatment before transplantation.7

There are other liver transplant practices that result in inequities for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Some liver transplant centers consider being on a medication for opioid use disorder a contraindication for transplantation—even if the individual is in recovery and abstaining from substances.8 Others mandate that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings prior to transplant. While mutual help groups, including AA, may benefit some individuals, different approaches work for different people.9 Other psychosocial interventions (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and residential treatment) and medications also help individuals reduce or stop drinking. Some meet their goals without any treatment. Addiction care works best when it respects autonomy and meets individuals where they are by allowing them to decide among options.

While organ allocations are a crystalized example of inequities in addiction care, they are also ethically complex. Many individuals—with and without SUD—die on waiting lists and must meet stringent transplantation criteria. However, we can at least remove the unnecessary biases that compound inequities in care people with SUD already face.

As Rosa’s liver succumbed, her kidneys failed too, and she required dialysis. She sensed what was coming. “I want everything…for now. I need to take care of my children.” I, too, wanted Rosa to live and see her youngest start kindergarten.

A few days before her discharge, I walked to the pharmacy and bought a purple journal. In a rare moment, I found Rosa alone in her room, without her ex-husband, sister, and mother, who rarely left her bedside. Together, we called AA and explored whether she could start participating in phone meetings from the hospital. I explained that one way to document a commitment to sobriety, as the transplant center’s rules dictated, was to attend and document AA meetings in this notebook. “In 5 months, you will be a liver transplant candidate,” I remember saying, wishing it to fruition.

I became Rosa’s primary care physician and saw her in clinic. Over the next few weeks, her skin took on an ashen tone. Sleep escaped her and her thoughts and speech blurred. Her walk slowed and she needed a wheelchair. The quiet fierceness that had defined her dissipated as encephalopathy took over. But until our last visit, she brought her purple journal, tracking the AA meetings she’d attended. Dialysis became intolerable, but not before Rosa made care arrangements for her girls. When that happened, she stopped dialysis and went to Mexico, where she died in her sleep after saying good-bye to her father.

Earlier access to healthcare and effective depression and AUD treatment could have saved Rosa’s life. While it was too late for her, as hospitalists we care for many others with substance-related complications and may miss opportunities to discuss and offer evidence-based addiction treatment. For example, we initiate the most up-to-date management for a patient’s gastrointestinal bleed but may leave the alcohol discussion for someone else. It is similar for other SUD: we treat cellulitis, epidural abscesses, bacteremia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure exacerbations, and other complications of SUD without addressing the root cause of the hospitalization—other than to prescribe abstinence from substance use or, at our worst, scold individuals for continuing to use.

But what can we offer? Most healthcare professionals still do not receive addiction education during training. Without tools, we enact temporizing measures, until patients return to the hospital or die.

In addition to increasing alcohol-related morbidity, there have also been increases in drug-related overdoses, fueled by COVID-19, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and stimulants.10 In the 12-month period ending April 2021, more than 100,000 individuals died of drug-related overdoses, the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a year.11 Despite this, most healthcare systems remain unequipped to provide addiction services during hospitalization due to inadequate training, stigma, and lack of systems-based care.

Hospitalists and healthcare systems cannot be bystanders amid our worsening addiction crisis. We must empower clinicians with addiction education and ensure health systems offer evidence-based SUD services.

Educational efforts can close the knowledge gaps for both medical students and hospitalists. Medical schools should include foundational curricular content in screening, assessing, diagnosing, and treating SUD in alignment with standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which accredits US medical schools. Residency programs can offer educational conferences, cased-based discussions, and addiction medicine rotations. Hospitalists can participate in educational didactics and review evidence-based addiction guidelines.12,13 While the focus here is on hospitalists, clinicians across practice settings and specialties will encounter patients with SUD, and all need to be well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of addiction given the all-hands-on deck approach necessary amidst our worsening addiction crisis.

With one in nine hospitalizations involving individuals with SUD, and this number quickly rising, and with an annual cost to US hospitals of $13.2 billion, healthcare system leaders must invest in addiction care.14,15 Hospital-based addiction services could pay for themselves and save healthcare systems money while improving the patient and clinician experience.16One way to implement hospital-based addiction care is through an addiction consult team (ACT).17 While ACT compositions vary, most are interprofessional, offer evidence-based addiction treatment, and connect patients to community care.18 Our hospital’s ACT has nurses, patient navigators, and physicians who assess, diagnose, and treat SUD, and arrange follow-up addiction care.19 In addition to caring for individual patients, our ACT has led systems change. For example, we created order sets to guide clinicians, added medications to our hospital formulary to ensure access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and partnered with community stakeholders to streamline care transitions and access to psychosocial and medication treatment. Our team also worked with hospital leadership, nursing, and a syringe service program to integrate hospital harm reduction education and supply provision. Additionally, we are building capacity among staff, trainees, and clinicians through education and systems changes.

In hospitals without an ACT, leadership can finance SUD champions and integrate them into policy-level decision-making to implement best practices in addiction care and lead hospital-wide educational efforts. This will transform hospital culture and improve care as all clinicians develop essential addiction skills.

Addiction champions and ACTs could also advocate for equitable practices for patients with SUD to reduce the stigma that both prevents patients from seeking care and results in self-discharges.20 For example, with interprofessional support, we revised our in-hospital substance use policy. It previously entailed hospital security responding to substance use concerns, which unintentionally harmed patients and perpetuated stigma. Our revised policy ensures we offer medications for cravings and withdrawal, adequate pain management, and other services that address patients’ reasons for in-hospital substance use.

With the increasing prevalence of SUD among hospitalized patients, escalating substance-related deaths, rising healthcare costs, and the impact of addiction on health and well-being, addiction care, including ACTs and champions, must be adequately funded. However, sustainable financing remains a challenge.18

Caring for Rosa and others with SUD sparked my desire to learn about addiction, obtain addiction medicine board certification as a practicing hospitalist, and create an ACT that offers evidence-based addiction treatment. While much remains to be done, by collaborating with addiction champions and engaging hospital leadership, we have transformed our hospital’s approach to substance use care.

With the knowledge and resources I now have as an addiction medicine physician, I reimagine the possibilities for patients like Rosa.

Rosa died when living was possible.

*Name has been changed for patient privacy.

Rosa* was one of my first patients as an intern rotating at the county hospital. Her marriage had disintegrated years earlier. To cope with depression, she hid a daily ritual of orange juice and vodka from her children. She worked as a cashier, until nausea and fatigue overwhelmed her.

The first time I met her she sat on the gurney: petite, tanned, and pregnant. Then I saw her yellow eyes and revised: temporal wasting, jaundiced, and swollen with ascites. Rosa didn’t know that alcohol could cause liver disease. Without insurance or access to primary care, her untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression had snowballed for years.

Midway through my intern year, I’d taken care of many people with AUD. However, I’d barely learned anything about it as a medical student, though we’d spent weeks studying esoteric diseases, that now––9 years after medical school––I still have not encountered.

Among the 28.3 million individuals in the United States with AUD, only 1% receive medication treatment.1 In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use accounts for more than 95,000 deaths each year.2 This number likely under-captures alcohol-related mortality and is higher now given recent reports of increasing alcohol-related deaths and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, especially among women, younger age groups, and marginalized populations.3-5

Rosa had alcohol-related hepatitis, which can cause severe inflammation and liver failure and quickly lead to death. As her liver failure progressed, I asked the gastroenterologists, “What other treatments can we offer? Is she a liver transplant candidate?” “Nothing” and “No” they answered.

Later, I emailed the hepatologist and transplant surgeon begging them to reevaluate her transplantation candidacy, but they told me there was no exception to the institution’s 6-month sobriety rule.

Maintaining a 6-month sobriety period is not an evidence-based criterion for transplantation. However, 50% of transplant centers do not perform transplantation prior to 6 months of alcohol abstinence for alcohol-related hepatitis due to concern for return to drinking after transplant.6 This practice may promote bias in patient selection for transplantation. A recent study found that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease transplanted before 6 months of abstinence had similar rates of survival and return to drinking compared to those who abstained from alcohol for 6 months and participated in AUD treatment before transplantation.7

There are other liver transplant practices that result in inequities for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Some liver transplant centers consider being on a medication for opioid use disorder a contraindication for transplantation—even if the individual is in recovery and abstaining from substances.8 Others mandate that individuals with alcohol-related liver disease attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings prior to transplant. While mutual help groups, including AA, may benefit some individuals, different approaches work for different people.9 Other psychosocial interventions (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and residential treatment) and medications also help individuals reduce or stop drinking. Some meet their goals without any treatment. Addiction care works best when it respects autonomy and meets individuals where they are by allowing them to decide among options.

While organ allocations are a crystalized example of inequities in addiction care, they are also ethically complex. Many individuals—with and without SUD—die on waiting lists and must meet stringent transplantation criteria. However, we can at least remove the unnecessary biases that compound inequities in care people with SUD already face.

As Rosa’s liver succumbed, her kidneys failed too, and she required dialysis. She sensed what was coming. “I want everything…for now. I need to take care of my children.” I, too, wanted Rosa to live and see her youngest start kindergarten.

A few days before her discharge, I walked to the pharmacy and bought a purple journal. In a rare moment, I found Rosa alone in her room, without her ex-husband, sister, and mother, who rarely left her bedside. Together, we called AA and explored whether she could start participating in phone meetings from the hospital. I explained that one way to document a commitment to sobriety, as the transplant center’s rules dictated, was to attend and document AA meetings in this notebook. “In 5 months, you will be a liver transplant candidate,” I remember saying, wishing it to fruition.

I became Rosa’s primary care physician and saw her in clinic. Over the next few weeks, her skin took on an ashen tone. Sleep escaped her and her thoughts and speech blurred. Her walk slowed and she needed a wheelchair. The quiet fierceness that had defined her dissipated as encephalopathy took over. But until our last visit, she brought her purple journal, tracking the AA meetings she’d attended. Dialysis became intolerable, but not before Rosa made care arrangements for her girls. When that happened, she stopped dialysis and went to Mexico, where she died in her sleep after saying good-bye to her father.

Earlier access to healthcare and effective depression and AUD treatment could have saved Rosa’s life. While it was too late for her, as hospitalists we care for many others with substance-related complications and may miss opportunities to discuss and offer evidence-based addiction treatment. For example, we initiate the most up-to-date management for a patient’s gastrointestinal bleed but may leave the alcohol discussion for someone else. It is similar for other SUD: we treat cellulitis, epidural abscesses, bacteremia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure exacerbations, and other complications of SUD without addressing the root cause of the hospitalization—other than to prescribe abstinence from substance use or, at our worst, scold individuals for continuing to use.

But what can we offer? Most healthcare professionals still do not receive addiction education during training. Without tools, we enact temporizing measures, until patients return to the hospital or die.

In addition to increasing alcohol-related morbidity, there have also been increases in drug-related overdoses, fueled by COVID-19, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and stimulants.10 In the 12-month period ending April 2021, more than 100,000 individuals died of drug-related overdoses, the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a year.11 Despite this, most healthcare systems remain unequipped to provide addiction services during hospitalization due to inadequate training, stigma, and lack of systems-based care.

Hospitalists and healthcare systems cannot be bystanders amid our worsening addiction crisis. We must empower clinicians with addiction education and ensure health systems offer evidence-based SUD services.

Educational efforts can close the knowledge gaps for both medical students and hospitalists. Medical schools should include foundational curricular content in screening, assessing, diagnosing, and treating SUD in alignment with standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which accredits US medical schools. Residency programs can offer educational conferences, cased-based discussions, and addiction medicine rotations. Hospitalists can participate in educational didactics and review evidence-based addiction guidelines.12,13 While the focus here is on hospitalists, clinicians across practice settings and specialties will encounter patients with SUD, and all need to be well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of addiction given the all-hands-on deck approach necessary amidst our worsening addiction crisis.

With one in nine hospitalizations involving individuals with SUD, and this number quickly rising, and with an annual cost to US hospitals of $13.2 billion, healthcare system leaders must invest in addiction care.14,15 Hospital-based addiction services could pay for themselves and save healthcare systems money while improving the patient and clinician experience.16One way to implement hospital-based addiction care is through an addiction consult team (ACT).17 While ACT compositions vary, most are interprofessional, offer evidence-based addiction treatment, and connect patients to community care.18 Our hospital’s ACT has nurses, patient navigators, and physicians who assess, diagnose, and treat SUD, and arrange follow-up addiction care.19 In addition to caring for individual patients, our ACT has led systems change. For example, we created order sets to guide clinicians, added medications to our hospital formulary to ensure access to evidence-based addiction treatment, and partnered with community stakeholders to streamline care transitions and access to psychosocial and medication treatment. Our team also worked with hospital leadership, nursing, and a syringe service program to integrate hospital harm reduction education and supply provision. Additionally, we are building capacity among staff, trainees, and clinicians through education and systems changes.

In hospitals without an ACT, leadership can finance SUD champions and integrate them into policy-level decision-making to implement best practices in addiction care and lead hospital-wide educational efforts. This will transform hospital culture and improve care as all clinicians develop essential addiction skills.

Addiction champions and ACTs could also advocate for equitable practices for patients with SUD to reduce the stigma that both prevents patients from seeking care and results in self-discharges.20 For example, with interprofessional support, we revised our in-hospital substance use policy. It previously entailed hospital security responding to substance use concerns, which unintentionally harmed patients and perpetuated stigma. Our revised policy ensures we offer medications for cravings and withdrawal, adequate pain management, and other services that address patients’ reasons for in-hospital substance use.

With the increasing prevalence of SUD among hospitalized patients, escalating substance-related deaths, rising healthcare costs, and the impact of addiction on health and well-being, addiction care, including ACTs and champions, must be adequately funded. However, sustainable financing remains a challenge.18

Caring for Rosa and others with SUD sparked my desire to learn about addiction, obtain addiction medicine board certification as a practicing hospitalist, and create an ACT that offers evidence-based addiction treatment. While much remains to be done, by collaborating with addiction champions and engaging hospital leadership, we have transformed our hospital’s approach to substance use care.

With the knowledge and resources I now have as an addiction medicine physician, I reimagine the possibilities for patients like Rosa.

Rosa died when living was possible.

*Name has been changed for patient privacy.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/data/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) application, 2013. Average for United States 2006–2010 alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/ARDI

3. Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451

4. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

5. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the covid-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942

6. Bangaru S, Pedersen MR, Macconmara MP, Singal AG, Mufti AR. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1357-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25285

7. Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1026-1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

8. Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(12):e13119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13119

9. Klimas J, Fairgrieve C, Tobin H, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009269.pub4

10. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

11. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

12. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

13. California Bridge Program. Tools: Treat substance use disorders from the acute care setting. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://cabridge.org/tools

14. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242

15. Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, et al. National prevalence of alcohol and other substance use disorders among emergency department visits and hospitalizations: NHAMCS 2014-2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;13:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w

16. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: Qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993

17. Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):822. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4

18. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496

19. Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(1):e001111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111

20. Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/data/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) application, 2013. Average for United States 2006–2010 alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/ARDI

3. Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451

4. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

5. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the covid-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942

6. Bangaru S, Pedersen MR, Macconmara MP, Singal AG, Mufti AR. Survey of liver transplantation practices for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1357-1362. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25285

7. Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, et al. Evaluation of early vs standard liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1026-1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

8. Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(12):e13119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13119

9. Klimas J, Fairgrieve C, Tobin H, et al. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009269.pub4

10. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

11. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

12. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

13. California Bridge Program. Tools: Treat substance use disorders from the acute care setting. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://cabridge.org/tools

14. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242

15. Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, et al. National prevalence of alcohol and other substance use disorders among emergency department visits and hospitalizations: NHAMCS 2014-2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;13:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w

16. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: Qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993

17. Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):822. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4

18. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496

19. Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(1):e001111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111

20. Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):519-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Things We Do for No Reason™: Prescribing Thiamine, Folate and Multivitamins on Discharge for Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is admitted with decompensated heart failure and experiences alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization. He improves with guideline-directed heart failure therapy and benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Discharge medications are metoprolol succinate, lisinopril, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin, thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin. No medications are offered for AUD treatment. At follow-up a week later, he presents with dyspnea and reports poor medication adherence and a return to heavy drinking.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IT IS HELPFUL TO PRESCRIBE VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION TO PATIENTS WITH AUD AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

AUD is common among hospitalized patients.1 AUD increases the risk of vitamin deficiencies due to the toxic effects of alcohol on the gastrointestinal tract and liver, causing impaired digestion, reduced absorption, and increased degradation of key micronutrients.2,3 Other risk factors for AUD-associated vitamin deficiencies include food insecurity and the replacement of nutrient-rich food with alcohol. Since the body does not readily store water-soluble vitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9), people require regular dietary replenishment of these nutrients. Thus, if individuals with AUD eat less fortified food, they risk developing thiamine, folate, niacin, and other vitamin deficiencies. Since AUD puts patients at risk for vitamin deficiencies, hospitalized patients typically receive vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin (most formulations contain water-soluble vitamins B and C and micronutrients).1 Hospitalists often continue these medications at discharge.

Thiamine deficiency may manifest as Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), peripheral neuropathy, or a high-output heart failure state.

Hospitalists empirically treat with thiamine, folate, and other vitamins upon hospital admission with the intent of reducing morbidity associated with nutritional deficiencies.1 Repletion poses few risks to patients since the kidneys eliminate water-soluble vitamins. Multivitamins also have a low potential for direct harm and a low cost. Given the consequences of missing a deficiency, alcohol withdrawal–management order sets commonly embed vitamin repletion orders.6

WHY ROUTINELY PRESCRIBING VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH AUD IS A TWDFNR

Hospitalists often reflexively continue vitamin supplementation on discharge. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that prescribing vitamin supplementation leads to clinically significant improvements for people with AUD, and patients can experience harms.

Literature and specialty guidelines lack consensus on rational vitamin supplementation in patients with AUD.2,7,8 Folate testing is not recommended due to inaccuracies.9 In fact, clinical data, such as body mass index, more accurately predict alcohol-related cognitive impairment than blood levels of vitamins.10 In one small study of vitamin deficiencies among patients with acute alcohol intoxication, none had low B12 or folate levels.11 A systematic review among people experiencing homelessness with unhealthy alcohol use showed no clear pattern of vitamin deficiencies across studies, although vitamin C and thiamine deficiencies predominated.12

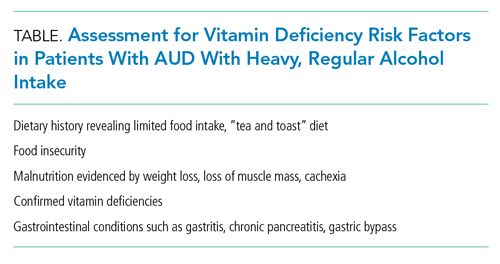

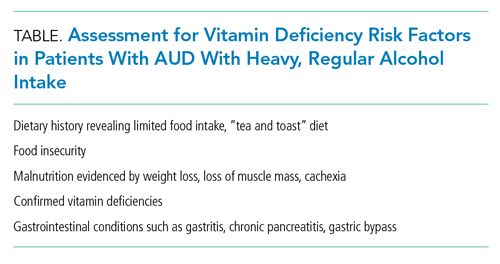

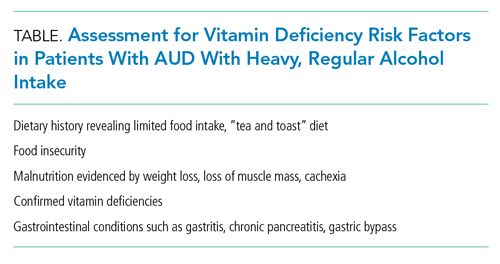

In the absence of reliable thiamine and folate testing to confirm deficiencies, clinicians must use their clinical assessment skills. Clinicians rarely evaluate patients with AUD for vitamin deficiency risk factors and instead reflexively prescribe vitamin supplementation. An AUD diagnosis may serve as a sensitive, but not specific, risk factor for those in need of vitamin supplementation.

Other limitations make prescribing oral vitamins reflexively at discharge a low-value practice. Thiamine, often prescribed orally in the hospital and on discharge, has poor oral bioavailability.13 Unfortunately, people with AUD have decreased and variable thiamine absorption. To prevent WE, thiamine must cross the blood-brain barrier, and the literature provides insufficient evidence to guide clinicians on an appropriate oral thiamine dose, frequency, or duration of treatment.14 While early high-dose IV thiamine may treat or prevent WE during hospitalization, low-dose oral thiamine may not provide benefit to patients with AUD.5

The literature also provides sparse evidence for folate supplementation and its optimal dose. Since 1998, when the United States mandated fortifying grain products with folic acid, people rarely have low serum folate levels. Though patients with AUD have lower folate levels relative to the general population,15 this difference does not seem clinically significant. While limited data show an association between oral multivitamin supplementation and improved serum nutrient levels among people with AUD, we lack evidence on clinical outcomes.16

Most importantly, for a practice lacking strong evidence, prescribing multiple vitamins at discharge may result in harm from polypharmacy and unnecessary costs for the recently hospitalized patient. Alcohol use is associated with decreased adherence to medications for chronic conditions,17 including HIV, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and psychiatric diseases. In addition, research shows an association between an increased number of discharge medications and higher risk for hospital readmission. The harm may actually correlate with the number of medications and complexity of the regimen rather than the risk profile of the medications themselves.18 Providers underestimate the impact of adding multiple vitamins at discharge, especially for patients who have several co-occurring medical conditions that require other medications. Furthermore, insurance rarely covers vitamins, leading hospitals or patients to incur the costs at discharge.

WHEN TO CONSIDER VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT DISCHARGE FOR PATIENTS WITH AUD

When treating patients with AUD, consider the potential benefit of vitamin supplementation for the individual. If a patient with regular, heavy alcohol use is at high risk of vitamin deficiencies due to ongoing risk factors (Table), hospitalists should discuss vitamin therapy via a patient-centered risk-benefit process.

When considering discharge vitamins, make concurrent efforts to enhance patient nutrition via decreased alcohol consumption and improved healthy food intake. While some patients do not have a goal of abstaining from alcohol, providing resources to food access may help decrease the harms of drinking. Education may help patients learn that vitamin deficiencies can result from heavy alcohol use.

Multivitamin formulations have variable doses of vitamins but can contain 100% or more of the daily value of thiamine and folic acid. For patients with AUD at lower risk of vitamin deficiencies (ie, mild alcohol use disorder with a healthy diet), discuss risks and benefits of supplementation. If they desire supplementation, a single thiamine-containing vitamin alone may be highest yield since it is the most morbid vitamin deficiency. Conversely, a patient with heavy alcohol intake and other risk factors for malnutrition may benefit from a higher dose of supplementation, achieved by prescribing a multivitamin alongside additional doses of thiamine and folate. However, the literature lacks evidence to guide clinicians on optimal vitamin dosing and formulations.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of reflexively prescribing thiamine, folate, and multivitamin, clinicians can assess patients for AUD, provide motivational interviewing, and offer AUD treatment. Hospitalists should initiate and prescribe evidence-based medications for AUD for patients interested in reducing or stopping their alcohol intake. We can choose from Food and Drug Administration–approved AUD medications, including naltrexone and acamprosate. Unfortunately, less than 3% of patients with AUD receive medication therapy.19 Our healthcare systems can also refer individuals to community psychosocial treatment.

For patients with risk factors, prescribe empiric IV thiamine during hospitalization. Clinicians should then perform a risk-benefit assessment rather than reflexively prescribe vitamins to patients with AUD at discharge. We should also counsel patients to eat food when drinking to decrease alcohol-related harms.20 Patients experiencing food insecurity should be linked to food resources through inpatient nutritional and social work consultations.

Elicit patient preference around vitamin supplementation after discharge. For patients with AUD who desire supplementation without risk factors for malnutrition (Table), consider prescribing a single thiamine-containing vitamin for prevention of thiamine deficiency, which, unlike other vitamin deficiencies, has the potential to be irreversible and life-threatening. Though no evidence currently supports this practice, it stands to reason that prescribing a single tablet could decrease the number of pills for patients who struggle with pill burden.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Offer evidence-based medication treatment for AUD.

- Connect patients experiencing food insecurity with appropriate resources.

- For patients initiated on a multivitamin, folate, and high-dose IV thiamine at admission, perform vitamin de-escalation during hospitalization.

- Risk-stratify hospitalized patients with AUD for additional risk factors for vitamin deficiencies (Table). In those with additional risk factors, offer supplementation if consistent with patient preference. Balance the benefits of vitamin supplementation with the risks of polypharmacy, particularly if the patient has conditions requiring multiple medications.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our case, the hospitalist initiates IV thiamine, folate, and a multivitamin at admission and assesses the patient’s nutritional status and food insecurity. The hospitalist deems the patient—who eats regular, balanced meals—to be at low risk for vitamin deficiencies. The medical team discontinues folate and multivitamins before discharge and continues IV thiamine throughout the 3-day hospitalization. The patient and clinician agree that unaddressed AUD played a key role in the patient’s heart failure exacerbation. The clinician elicits the patient’s goals around their alcohol use, discusses AUD treatment, and initiates naltrexone for AUD.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

1. Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-8-11

2. Lewis MJ. Alcoholism and nutrition: a review of vitamin supplementation and treatment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23(2):138-144. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000622

3. Bergmans RS, Coughlin L, Wilson T, Malecki K. Cross-sectional associations of food insecurity with smoking cigarettes and heavy alcohol use in a population-based sample of adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107646

4. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):911-915. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12522

5. Flannery AH, Adkins DA, Cook AM. Unpeeling the evidence for the banana bag: evidence-based recommendations for the management of alcohol-associated vitamin and electrolyte deficiencies in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1545-1552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000001659

6. Wai JM, Aloezos C, Mowrey WB, Baron SW, Cregin R, Forman HL. Using clinical decision support through the electronic medical record to increase prescribing of high-dose parenteral thiamine in hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:117-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.017

7. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. January 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/quality-science/the_asam_clinical_practice_guideline_on_alcohol-1.pdf?sfvrsn=ba255c2_2

8. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):307-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23258

9. Breu AC, Theisen-Toupal J, Feldman LS. Serum and red blood cell folate testing on hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):753-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2385

10. Gautron M-A, Questel F, Lejoyeux M, Bellivier F, Vorspan F. Nutritional status during inpatient alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(1):64-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx086

11. Li SF, Jacob J, Feng J, Kulkarni M. Vitamin deficiencies in acutely intoxicated patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(7):792-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.003

12. Ijaz S, Jackson J, Thorley H, et al. Nutritional deficiencies in homeless persons with problematic drinking: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0564-4

13. Day GS, Ladak S, Curley K, et al. Thiamine prescribing practices within university-affiliated hospitals: a multicenter retrospective review. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):246-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2324

14. Day E, Bentham PW, Callaghan R, Kuruvilla T, George S. Thiamine for prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in people who abuse alcohol. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(7):CD004033. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004033.pub3

15. Medici V, Halsted CH. Folate, alcohol, and liver disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(4):596-606. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200077

16. Ijaz S, Thorley H, Porter K, et al. Interventions for preventing or treating malnutrition in homeless problem-drinkers: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0722-3

17. Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(11):795-803. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004

18. Picker D, Heard K, Bailey TC, Martin NR, LaRossa GN, Kollef MH. The number of discharge medications predicts thirty-day hospital readmission: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0950-9

19. Han B, Jones CM, Einstein EB, Powell PA, Compton WM. Use of medications for alcohol use disorder in the US: results From the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(8):922–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1271

20. Collins SE, Duncan MH, Saxon AJ, et al. Combining behavioral harm-reduction treatment and extended-release naltrexone for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorder in the USA: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):287-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30489-2

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is admitted with decompensated heart failure and experiences alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization. He improves with guideline-directed heart failure therapy and benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Discharge medications are metoprolol succinate, lisinopril, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin, thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin. No medications are offered for AUD treatment. At follow-up a week later, he presents with dyspnea and reports poor medication adherence and a return to heavy drinking.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IT IS HELPFUL TO PRESCRIBE VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION TO PATIENTS WITH AUD AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

AUD is common among hospitalized patients.1 AUD increases the risk of vitamin deficiencies due to the toxic effects of alcohol on the gastrointestinal tract and liver, causing impaired digestion, reduced absorption, and increased degradation of key micronutrients.2,3 Other risk factors for AUD-associated vitamin deficiencies include food insecurity and the replacement of nutrient-rich food with alcohol. Since the body does not readily store water-soluble vitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9), people require regular dietary replenishment of these nutrients. Thus, if individuals with AUD eat less fortified food, they risk developing thiamine, folate, niacin, and other vitamin deficiencies. Since AUD puts patients at risk for vitamin deficiencies, hospitalized patients typically receive vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin (most formulations contain water-soluble vitamins B and C and micronutrients).1 Hospitalists often continue these medications at discharge.

Thiamine deficiency may manifest as Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), peripheral neuropathy, or a high-output heart failure state.

Hospitalists empirically treat with thiamine, folate, and other vitamins upon hospital admission with the intent of reducing morbidity associated with nutritional deficiencies.1 Repletion poses few risks to patients since the kidneys eliminate water-soluble vitamins. Multivitamins also have a low potential for direct harm and a low cost. Given the consequences of missing a deficiency, alcohol withdrawal–management order sets commonly embed vitamin repletion orders.6

WHY ROUTINELY PRESCRIBING VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH AUD IS A TWDFNR

Hospitalists often reflexively continue vitamin supplementation on discharge. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that prescribing vitamin supplementation leads to clinically significant improvements for people with AUD, and patients can experience harms.

Literature and specialty guidelines lack consensus on rational vitamin supplementation in patients with AUD.2,7,8 Folate testing is not recommended due to inaccuracies.9 In fact, clinical data, such as body mass index, more accurately predict alcohol-related cognitive impairment than blood levels of vitamins.10 In one small study of vitamin deficiencies among patients with acute alcohol intoxication, none had low B12 or folate levels.11 A systematic review among people experiencing homelessness with unhealthy alcohol use showed no clear pattern of vitamin deficiencies across studies, although vitamin C and thiamine deficiencies predominated.12

In the absence of reliable thiamine and folate testing to confirm deficiencies, clinicians must use their clinical assessment skills. Clinicians rarely evaluate patients with AUD for vitamin deficiency risk factors and instead reflexively prescribe vitamin supplementation. An AUD diagnosis may serve as a sensitive, but not specific, risk factor for those in need of vitamin supplementation.

Other limitations make prescribing oral vitamins reflexively at discharge a low-value practice. Thiamine, often prescribed orally in the hospital and on discharge, has poor oral bioavailability.13 Unfortunately, people with AUD have decreased and variable thiamine absorption. To prevent WE, thiamine must cross the blood-brain barrier, and the literature provides insufficient evidence to guide clinicians on an appropriate oral thiamine dose, frequency, or duration of treatment.14 While early high-dose IV thiamine may treat or prevent WE during hospitalization, low-dose oral thiamine may not provide benefit to patients with AUD.5

The literature also provides sparse evidence for folate supplementation and its optimal dose. Since 1998, when the United States mandated fortifying grain products with folic acid, people rarely have low serum folate levels. Though patients with AUD have lower folate levels relative to the general population,15 this difference does not seem clinically significant. While limited data show an association between oral multivitamin supplementation and improved serum nutrient levels among people with AUD, we lack evidence on clinical outcomes.16

Most importantly, for a practice lacking strong evidence, prescribing multiple vitamins at discharge may result in harm from polypharmacy and unnecessary costs for the recently hospitalized patient. Alcohol use is associated with decreased adherence to medications for chronic conditions,17 including HIV, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and psychiatric diseases. In addition, research shows an association between an increased number of discharge medications and higher risk for hospital readmission. The harm may actually correlate with the number of medications and complexity of the regimen rather than the risk profile of the medications themselves.18 Providers underestimate the impact of adding multiple vitamins at discharge, especially for patients who have several co-occurring medical conditions that require other medications. Furthermore, insurance rarely covers vitamins, leading hospitals or patients to incur the costs at discharge.

WHEN TO CONSIDER VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT DISCHARGE FOR PATIENTS WITH AUD

When treating patients with AUD, consider the potential benefit of vitamin supplementation for the individual. If a patient with regular, heavy alcohol use is at high risk of vitamin deficiencies due to ongoing risk factors (Table), hospitalists should discuss vitamin therapy via a patient-centered risk-benefit process.

When considering discharge vitamins, make concurrent efforts to enhance patient nutrition via decreased alcohol consumption and improved healthy food intake. While some patients do not have a goal of abstaining from alcohol, providing resources to food access may help decrease the harms of drinking. Education may help patients learn that vitamin deficiencies can result from heavy alcohol use.

Multivitamin formulations have variable doses of vitamins but can contain 100% or more of the daily value of thiamine and folic acid. For patients with AUD at lower risk of vitamin deficiencies (ie, mild alcohol use disorder with a healthy diet), discuss risks and benefits of supplementation. If they desire supplementation, a single thiamine-containing vitamin alone may be highest yield since it is the most morbid vitamin deficiency. Conversely, a patient with heavy alcohol intake and other risk factors for malnutrition may benefit from a higher dose of supplementation, achieved by prescribing a multivitamin alongside additional doses of thiamine and folate. However, the literature lacks evidence to guide clinicians on optimal vitamin dosing and formulations.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of reflexively prescribing thiamine, folate, and multivitamin, clinicians can assess patients for AUD, provide motivational interviewing, and offer AUD treatment. Hospitalists should initiate and prescribe evidence-based medications for AUD for patients interested in reducing or stopping their alcohol intake. We can choose from Food and Drug Administration–approved AUD medications, including naltrexone and acamprosate. Unfortunately, less than 3% of patients with AUD receive medication therapy.19 Our healthcare systems can also refer individuals to community psychosocial treatment.

For patients with risk factors, prescribe empiric IV thiamine during hospitalization. Clinicians should then perform a risk-benefit assessment rather than reflexively prescribe vitamins to patients with AUD at discharge. We should also counsel patients to eat food when drinking to decrease alcohol-related harms.20 Patients experiencing food insecurity should be linked to food resources through inpatient nutritional and social work consultations.

Elicit patient preference around vitamin supplementation after discharge. For patients with AUD who desire supplementation without risk factors for malnutrition (Table), consider prescribing a single thiamine-containing vitamin for prevention of thiamine deficiency, which, unlike other vitamin deficiencies, has the potential to be irreversible and life-threatening. Though no evidence currently supports this practice, it stands to reason that prescribing a single tablet could decrease the number of pills for patients who struggle with pill burden.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Offer evidence-based medication treatment for AUD.

- Connect patients experiencing food insecurity with appropriate resources.

- For patients initiated on a multivitamin, folate, and high-dose IV thiamine at admission, perform vitamin de-escalation during hospitalization.

- Risk-stratify hospitalized patients with AUD for additional risk factors for vitamin deficiencies (Table). In those with additional risk factors, offer supplementation if consistent with patient preference. Balance the benefits of vitamin supplementation with the risks of polypharmacy, particularly if the patient has conditions requiring multiple medications.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our case, the hospitalist initiates IV thiamine, folate, and a multivitamin at admission and assesses the patient’s nutritional status and food insecurity. The hospitalist deems the patient—who eats regular, balanced meals—to be at low risk for vitamin deficiencies. The medical team discontinues folate and multivitamins before discharge and continues IV thiamine throughout the 3-day hospitalization. The patient and clinician agree that unaddressed AUD played a key role in the patient’s heart failure exacerbation. The clinician elicits the patient’s goals around their alcohol use, discusses AUD treatment, and initiates naltrexone for AUD.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is admitted with decompensated heart failure and experiences alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization. He improves with guideline-directed heart failure therapy and benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Discharge medications are metoprolol succinate, lisinopril, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin, thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin. No medications are offered for AUD treatment. At follow-up a week later, he presents with dyspnea and reports poor medication adherence and a return to heavy drinking.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IT IS HELPFUL TO PRESCRIBE VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION TO PATIENTS WITH AUD AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

AUD is common among hospitalized patients.1 AUD increases the risk of vitamin deficiencies due to the toxic effects of alcohol on the gastrointestinal tract and liver, causing impaired digestion, reduced absorption, and increased degradation of key micronutrients.2,3 Other risk factors for AUD-associated vitamin deficiencies include food insecurity and the replacement of nutrient-rich food with alcohol. Since the body does not readily store water-soluble vitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9), people require regular dietary replenishment of these nutrients. Thus, if individuals with AUD eat less fortified food, they risk developing thiamine, folate, niacin, and other vitamin deficiencies. Since AUD puts patients at risk for vitamin deficiencies, hospitalized patients typically receive vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin (most formulations contain water-soluble vitamins B and C and micronutrients).1 Hospitalists often continue these medications at discharge.

Thiamine deficiency may manifest as Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), peripheral neuropathy, or a high-output heart failure state.

Hospitalists empirically treat with thiamine, folate, and other vitamins upon hospital admission with the intent of reducing morbidity associated with nutritional deficiencies.1 Repletion poses few risks to patients since the kidneys eliminate water-soluble vitamins. Multivitamins also have a low potential for direct harm and a low cost. Given the consequences of missing a deficiency, alcohol withdrawal–management order sets commonly embed vitamin repletion orders.6

WHY ROUTINELY PRESCRIBING VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH AUD IS A TWDFNR

Hospitalists often reflexively continue vitamin supplementation on discharge. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that prescribing vitamin supplementation leads to clinically significant improvements for people with AUD, and patients can experience harms.

Literature and specialty guidelines lack consensus on rational vitamin supplementation in patients with AUD.2,7,8 Folate testing is not recommended due to inaccuracies.9 In fact, clinical data, such as body mass index, more accurately predict alcohol-related cognitive impairment than blood levels of vitamins.10 In one small study of vitamin deficiencies among patients with acute alcohol intoxication, none had low B12 or folate levels.11 A systematic review among people experiencing homelessness with unhealthy alcohol use showed no clear pattern of vitamin deficiencies across studies, although vitamin C and thiamine deficiencies predominated.12