User login

Converging Crises: Caring for Hospitalized Adults With Substance Use Disorder in the Time of COVID-19

The spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind the COVID-19 pandemic, has converged with an unrelenting addiction epidemic. These combined crises will have profound effects on people with substance use disorders (SUD) and people in recovery. Hospitals—which were already hit hard by the addiction epidemic—are the last line of defense in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitalists have an important role in balancing the effects of these intersecting, synergistic crises.

People with SUD are disproportionately affected by major medical illnesses, including infections such as hepatitis C, HIV, and cardiovascular, pulmonary, and liver diseases.1 They also experience high rates of hospitalization due to drug-related infections, injury, and overdose.2 People with SUD commonly have intersecting vulnerabilities that may affect their healthcare experience and health outcomes, including housing and food insecurity, mental illness, and experiences of racism, incarceration, and other trauma. They may also harbor mistrust of healthcare providers because of previous negative encounters and discrimination with health systems.3 These vulnerabilities increase risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic may drive increases in use and harms from SUD among patients who already have an SUD, with widespread job loss, insurance loss,6 anxiety, and social isolation on the rise. We may also see increases in return to use among people in recovery or new substance use among those without a history of SUD.

The intersecting crises of SUD and COVID-19 are important for people with SUD and for public health. In this perspective, we describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with SUD and share practical resources for hospital providers to improve care for people with SUD during the pandemic and beyond.

CONTEXTUALIZING COVID-19 AND SUD RISK

Mistrust of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers

Fear of stigmatization is an ongoing problem for people with SUD, who often experience discrimination in hospitals and, as a result, may avoid hospital care.7 Much of this stigma is based on the false but persistent belief—widespread even among healthcare providers—that addiction is the result of bad choices and limited willpower; however, the science is clear that addiction is a disorder with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental underpinnings.3 These attitudes are likely to be amplified during COVID-19, as patients and providers experience higher levels of stress.

Increased Risks of Substance Use

Typically, people who use drugs are counseled to use with others nearby so that they might administer naloxone or call 911 in the event of an overdose.8 With physical distancing, people may be more likely to use alone. COVID-19 also introduces uncertainty into the drug supply chain through changes in drug production and trafficking.9 Further, access to alcohol may be limited as liquor stores close and public transportation becomes less available. As has been shown in other complex emergencies (such as social, political, economic, and environmental disasters), these barriers to obtaining substances may increase risks for withdrawal, for needing to exchange sex for money or drugs, for sharing syringes or drug preparation equipment,10 or for consuming other available sources of substances, like rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer. COVID-19 may also increase risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidality, all of which increase risk for return to use and overdose.

Changes to the Treatment Milieu

Many of the resources and services that people who use substances rely on to keep safe may be disrupted by COVID-19. Social distancing—the cornerstone of mitigating COVID-19 spread—may be challenging among people with SUD. Though federal regulations around methadone dispensing and buprenorphine prescribing have loosened in response to the pandemic,11 individuals in treatment may still be required to provide urine drug screens or be physically present to receive methadone doses, sometimes daily and in crowded waiting rooms.

Recovery support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) provide social connection and are the foundation of many people’s recovery. While many in-person meetings have rapidly transformed to online and telephone support, they remain inaccessible to the most marginalized members of communities: people without smart phones, computers, or internet. This digital shift may also disproportionately affect older adults, people with limited English proficiency, and people with low technological literacy. Limits for other resources, such as syringe service programs, community centers, food pantries, housing shelters, and other places that people depend on for clean water, food, showers, soap, and safer spaces to use, may limit services or close altogether; those that remain open may see an unprecedented rise in need for services as millions of Americans file for unemployment. For many, anxiety about the pandemic, unemployment, financial strain, increased isolation, family stressors, illness, and community losses can lead to enormous personal distress and trigger return to use; loss of a recovery network may further exacerbate this.

Intersectionality of SUD and Other Structural Inequities

Many of the inequities that increase people’s risk for undertreated SUD also increase risk for COVID-19 infection, including racism,12 poverty, and homelessness.4 “Stay home and stay safe” is not an option for people who are unsheltered or whose homes are unsafe because of risks of physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Poverty commonly forces people to live in crowded communal apartments or shelters, rely on public transportation, wait in long lines at food pantries, and continue to work, even if unwell. Many shelters have had to reduce the number of people they serve to reduce crowding and support social distancing, which further compounds risks of unstable housing. Unfortunately, the same structural inequities that exacerbate SUD worsen the COVID-19 crisis.13

ROLE FOR HOSPITALISTS

The intersecting vulnerabilities of SUD and COVID-19 heighten an already urgent need to address SUD among hospitalized patients.14 While COVID-19 may increase harms of substance use, it may also increase people’s readiness to engage in treatment given changes to the drug supply and patient’s concerns about health risks. As such, it is even more critical to make treatment readily accessible and support harm reduction. Hospitalists can take important, actionable steps for patients with SUD—many of which are good general practices14 (Appendix Table).

Hospitalists should do the following:

1. Identify and treat acute withdrawal.15

2. Manage acute pain, including providing high-dose opioids if needed.16 Both practices (1 and 2) are evidence-based, can promote patient’s trust in providers,17 and can help avoid patients leaving against medical advice (AMA). Leaving AMA can lead to poor individual health and further threaten public health if patients leave with undiagnosed or unmanaged COVID-19 infection.

3. Encourage their hospitals to provide patients with tablets or other means to communicate with family, friends, and recovery supports via videolink, and refer patients to virtual peer support and recovery meetings during hospitalization.18 These practices may further support patients in tolerating hospitalization and prevent AMA discharge.

4. Initiate medication for addiction during admission and refer to addictions treatment after discharge. COVID-19–related regulatory changes such as expanded telehealth buprenorphine options and fewer daily dosing requirements for methadone may make this easier. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol and tobacco use disorders,15 especially given heightened possibility of unhealthy alcohol use and the respiratory complications associated with both tobacco and COVID-19.

5. Assess mental health and suicide risks19 given their association with social isolation, job loss, and financial insecurity.

6. Discuss relapse prevention among people in recovery.

7. Assess overdose risk and promote harm reduction.19 Specifically, this may include counseling patients to avoid sharing smoking supplies to avoid COVID-19 transmission, identifying places to access clean syringes, prescribing naloxone,20 and providing supports so that, if patients need to use alone, they can do so more safely.21

8. Consider high-risk transitions that may be exacerbated by COVID-19. COVID-19 may make safe discharge plans among people experiencing homelessness very challenging. Some communities are rapidly repurposing existing spaces or building new ones to care for people without a safe place to recover after acute hospitalization, yet many communities have no such resources. Hospital teams should consider the possibility that community services and SUD treatment resources may change rapidly during the pandemic. Hospitals can maintain updated resource lists and consider partnering with state and local health departments to improve safe care for people experiencing homelessness or lacking basic services.

COVID-19 is putting enormous strain on many US hospitals. Hospital-based addictions care is under resourced in the best of times,14 and while some hospitals have addiction consult services, many do not. To what degree hospitalists and hospital teams can address anything beyond COVID-19 emergencies will vary based on settings and resources. Furthermore, we recognize that who performs various activities will depend on individual hospital’s resources and practices. Addiction consult services, if available, can play a critical role, as can hospital social workers and care managers, nurses, residents, students, and other members of the healthcare team.

Finally, though COVID-19 adds tremendous stress to hospitals, permanent improvements in SUD treatment systems such as telephone visits for buprenorphine or eased methadone restrictions may emerge that could reduce barriers to hospital-based addictions care.11 Leveraging these changes now may help hospital providers to better support patients long-term.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization can be a challenging time for patients with SUD and for the hospital teams who care for them. These tensions are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet hospitalists play a critical role in addressing the converging crises of SUD and COVID-19. Providing comprehensive, compassionate, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with SUD is important for both individual and community health during COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr King received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (UG1DA015815) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037441). Dr Snyder received a Public Health Institute grant payable to her institution.

1. Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated health care system. J Addict Med. 2017;11(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000260

2. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424

3. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

4. Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30085-2

5. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

6. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Intersecting U.S. epidemics: COVID-19 and lack of health insurance. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):63-64. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-1491

7. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a ‘risk environment’: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010

8. Harm Reduction Coalition. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://harmreduction.org/

9. COVID-19 and the drug supply chain: from production and trafficking to use. Global Research Network, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020. http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf

10. Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Nikolopoulos GK, Friedman SR. Immediate impact of hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):878-884. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.978675

11. FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf

12. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

13. Baggett TP, Lewis E, Gaeta JM. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness: early evidence from Boston. Ann Fam Med. Preprint posted April 4, 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/154734

14. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

15. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001

16. Quality & Science. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://www.asam.org/Quality-Science/quality

17. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. Published online December 12, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

18. Digital Recovery Support Services. Recovery Link. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://myrecoverylink.com/digital-recovery-support/

19. Publications and Digital Products: Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage for Clinicians. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. September 2009. Accessed April 4, 2020. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAFE-T-Pocket-Card-Suicide-Assessment-Five-Step-Evaluation-and-Triage-for-Clinicians/sma09-4432

20. Prescribe to Prevent: Prescribe Naloxone, Save a Life. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://prescribetoprevent.org/

21. Never Use Alone. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://neverusealone.com/

The spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind the COVID-19 pandemic, has converged with an unrelenting addiction epidemic. These combined crises will have profound effects on people with substance use disorders (SUD) and people in recovery. Hospitals—which were already hit hard by the addiction epidemic—are the last line of defense in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitalists have an important role in balancing the effects of these intersecting, synergistic crises.

People with SUD are disproportionately affected by major medical illnesses, including infections such as hepatitis C, HIV, and cardiovascular, pulmonary, and liver diseases.1 They also experience high rates of hospitalization due to drug-related infections, injury, and overdose.2 People with SUD commonly have intersecting vulnerabilities that may affect their healthcare experience and health outcomes, including housing and food insecurity, mental illness, and experiences of racism, incarceration, and other trauma. They may also harbor mistrust of healthcare providers because of previous negative encounters and discrimination with health systems.3 These vulnerabilities increase risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic may drive increases in use and harms from SUD among patients who already have an SUD, with widespread job loss, insurance loss,6 anxiety, and social isolation on the rise. We may also see increases in return to use among people in recovery or new substance use among those without a history of SUD.

The intersecting crises of SUD and COVID-19 are important for people with SUD and for public health. In this perspective, we describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with SUD and share practical resources for hospital providers to improve care for people with SUD during the pandemic and beyond.

CONTEXTUALIZING COVID-19 AND SUD RISK

Mistrust of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers

Fear of stigmatization is an ongoing problem for people with SUD, who often experience discrimination in hospitals and, as a result, may avoid hospital care.7 Much of this stigma is based on the false but persistent belief—widespread even among healthcare providers—that addiction is the result of bad choices and limited willpower; however, the science is clear that addiction is a disorder with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental underpinnings.3 These attitudes are likely to be amplified during COVID-19, as patients and providers experience higher levels of stress.

Increased Risks of Substance Use

Typically, people who use drugs are counseled to use with others nearby so that they might administer naloxone or call 911 in the event of an overdose.8 With physical distancing, people may be more likely to use alone. COVID-19 also introduces uncertainty into the drug supply chain through changes in drug production and trafficking.9 Further, access to alcohol may be limited as liquor stores close and public transportation becomes less available. As has been shown in other complex emergencies (such as social, political, economic, and environmental disasters), these barriers to obtaining substances may increase risks for withdrawal, for needing to exchange sex for money or drugs, for sharing syringes or drug preparation equipment,10 or for consuming other available sources of substances, like rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer. COVID-19 may also increase risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidality, all of which increase risk for return to use and overdose.

Changes to the Treatment Milieu

Many of the resources and services that people who use substances rely on to keep safe may be disrupted by COVID-19. Social distancing—the cornerstone of mitigating COVID-19 spread—may be challenging among people with SUD. Though federal regulations around methadone dispensing and buprenorphine prescribing have loosened in response to the pandemic,11 individuals in treatment may still be required to provide urine drug screens or be physically present to receive methadone doses, sometimes daily and in crowded waiting rooms.

Recovery support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) provide social connection and are the foundation of many people’s recovery. While many in-person meetings have rapidly transformed to online and telephone support, they remain inaccessible to the most marginalized members of communities: people without smart phones, computers, or internet. This digital shift may also disproportionately affect older adults, people with limited English proficiency, and people with low technological literacy. Limits for other resources, such as syringe service programs, community centers, food pantries, housing shelters, and other places that people depend on for clean water, food, showers, soap, and safer spaces to use, may limit services or close altogether; those that remain open may see an unprecedented rise in need for services as millions of Americans file for unemployment. For many, anxiety about the pandemic, unemployment, financial strain, increased isolation, family stressors, illness, and community losses can lead to enormous personal distress and trigger return to use; loss of a recovery network may further exacerbate this.

Intersectionality of SUD and Other Structural Inequities

Many of the inequities that increase people’s risk for undertreated SUD also increase risk for COVID-19 infection, including racism,12 poverty, and homelessness.4 “Stay home and stay safe” is not an option for people who are unsheltered or whose homes are unsafe because of risks of physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Poverty commonly forces people to live in crowded communal apartments or shelters, rely on public transportation, wait in long lines at food pantries, and continue to work, even if unwell. Many shelters have had to reduce the number of people they serve to reduce crowding and support social distancing, which further compounds risks of unstable housing. Unfortunately, the same structural inequities that exacerbate SUD worsen the COVID-19 crisis.13

ROLE FOR HOSPITALISTS

The intersecting vulnerabilities of SUD and COVID-19 heighten an already urgent need to address SUD among hospitalized patients.14 While COVID-19 may increase harms of substance use, it may also increase people’s readiness to engage in treatment given changes to the drug supply and patient’s concerns about health risks. As such, it is even more critical to make treatment readily accessible and support harm reduction. Hospitalists can take important, actionable steps for patients with SUD—many of which are good general practices14 (Appendix Table).

Hospitalists should do the following:

1. Identify and treat acute withdrawal.15

2. Manage acute pain, including providing high-dose opioids if needed.16 Both practices (1 and 2) are evidence-based, can promote patient’s trust in providers,17 and can help avoid patients leaving against medical advice (AMA). Leaving AMA can lead to poor individual health and further threaten public health if patients leave with undiagnosed or unmanaged COVID-19 infection.

3. Encourage their hospitals to provide patients with tablets or other means to communicate with family, friends, and recovery supports via videolink, and refer patients to virtual peer support and recovery meetings during hospitalization.18 These practices may further support patients in tolerating hospitalization and prevent AMA discharge.

4. Initiate medication for addiction during admission and refer to addictions treatment after discharge. COVID-19–related regulatory changes such as expanded telehealth buprenorphine options and fewer daily dosing requirements for methadone may make this easier. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol and tobacco use disorders,15 especially given heightened possibility of unhealthy alcohol use and the respiratory complications associated with both tobacco and COVID-19.

5. Assess mental health and suicide risks19 given their association with social isolation, job loss, and financial insecurity.

6. Discuss relapse prevention among people in recovery.

7. Assess overdose risk and promote harm reduction.19 Specifically, this may include counseling patients to avoid sharing smoking supplies to avoid COVID-19 transmission, identifying places to access clean syringes, prescribing naloxone,20 and providing supports so that, if patients need to use alone, they can do so more safely.21

8. Consider high-risk transitions that may be exacerbated by COVID-19. COVID-19 may make safe discharge plans among people experiencing homelessness very challenging. Some communities are rapidly repurposing existing spaces or building new ones to care for people without a safe place to recover after acute hospitalization, yet many communities have no such resources. Hospital teams should consider the possibility that community services and SUD treatment resources may change rapidly during the pandemic. Hospitals can maintain updated resource lists and consider partnering with state and local health departments to improve safe care for people experiencing homelessness or lacking basic services.

COVID-19 is putting enormous strain on many US hospitals. Hospital-based addictions care is under resourced in the best of times,14 and while some hospitals have addiction consult services, many do not. To what degree hospitalists and hospital teams can address anything beyond COVID-19 emergencies will vary based on settings and resources. Furthermore, we recognize that who performs various activities will depend on individual hospital’s resources and practices. Addiction consult services, if available, can play a critical role, as can hospital social workers and care managers, nurses, residents, students, and other members of the healthcare team.

Finally, though COVID-19 adds tremendous stress to hospitals, permanent improvements in SUD treatment systems such as telephone visits for buprenorphine or eased methadone restrictions may emerge that could reduce barriers to hospital-based addictions care.11 Leveraging these changes now may help hospital providers to better support patients long-term.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization can be a challenging time for patients with SUD and for the hospital teams who care for them. These tensions are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet hospitalists play a critical role in addressing the converging crises of SUD and COVID-19. Providing comprehensive, compassionate, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with SUD is important for both individual and community health during COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr King received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (UG1DA015815) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037441). Dr Snyder received a Public Health Institute grant payable to her institution.

The spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind the COVID-19 pandemic, has converged with an unrelenting addiction epidemic. These combined crises will have profound effects on people with substance use disorders (SUD) and people in recovery. Hospitals—which were already hit hard by the addiction epidemic—are the last line of defense in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitalists have an important role in balancing the effects of these intersecting, synergistic crises.

People with SUD are disproportionately affected by major medical illnesses, including infections such as hepatitis C, HIV, and cardiovascular, pulmonary, and liver diseases.1 They also experience high rates of hospitalization due to drug-related infections, injury, and overdose.2 People with SUD commonly have intersecting vulnerabilities that may affect their healthcare experience and health outcomes, including housing and food insecurity, mental illness, and experiences of racism, incarceration, and other trauma. They may also harbor mistrust of healthcare providers because of previous negative encounters and discrimination with health systems.3 These vulnerabilities increase risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic may drive increases in use and harms from SUD among patients who already have an SUD, with widespread job loss, insurance loss,6 anxiety, and social isolation on the rise. We may also see increases in return to use among people in recovery or new substance use among those without a history of SUD.

The intersecting crises of SUD and COVID-19 are important for people with SUD and for public health. In this perspective, we describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with SUD and share practical resources for hospital providers to improve care for people with SUD during the pandemic and beyond.

CONTEXTUALIZING COVID-19 AND SUD RISK

Mistrust of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers

Fear of stigmatization is an ongoing problem for people with SUD, who often experience discrimination in hospitals and, as a result, may avoid hospital care.7 Much of this stigma is based on the false but persistent belief—widespread even among healthcare providers—that addiction is the result of bad choices and limited willpower; however, the science is clear that addiction is a disorder with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental underpinnings.3 These attitudes are likely to be amplified during COVID-19, as patients and providers experience higher levels of stress.

Increased Risks of Substance Use

Typically, people who use drugs are counseled to use with others nearby so that they might administer naloxone or call 911 in the event of an overdose.8 With physical distancing, people may be more likely to use alone. COVID-19 also introduces uncertainty into the drug supply chain through changes in drug production and trafficking.9 Further, access to alcohol may be limited as liquor stores close and public transportation becomes less available. As has been shown in other complex emergencies (such as social, political, economic, and environmental disasters), these barriers to obtaining substances may increase risks for withdrawal, for needing to exchange sex for money or drugs, for sharing syringes or drug preparation equipment,10 or for consuming other available sources of substances, like rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer. COVID-19 may also increase risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidality, all of which increase risk for return to use and overdose.

Changes to the Treatment Milieu

Many of the resources and services that people who use substances rely on to keep safe may be disrupted by COVID-19. Social distancing—the cornerstone of mitigating COVID-19 spread—may be challenging among people with SUD. Though federal regulations around methadone dispensing and buprenorphine prescribing have loosened in response to the pandemic,11 individuals in treatment may still be required to provide urine drug screens or be physically present to receive methadone doses, sometimes daily and in crowded waiting rooms.

Recovery support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) provide social connection and are the foundation of many people’s recovery. While many in-person meetings have rapidly transformed to online and telephone support, they remain inaccessible to the most marginalized members of communities: people without smart phones, computers, or internet. This digital shift may also disproportionately affect older adults, people with limited English proficiency, and people with low technological literacy. Limits for other resources, such as syringe service programs, community centers, food pantries, housing shelters, and other places that people depend on for clean water, food, showers, soap, and safer spaces to use, may limit services or close altogether; those that remain open may see an unprecedented rise in need for services as millions of Americans file for unemployment. For many, anxiety about the pandemic, unemployment, financial strain, increased isolation, family stressors, illness, and community losses can lead to enormous personal distress and trigger return to use; loss of a recovery network may further exacerbate this.

Intersectionality of SUD and Other Structural Inequities

Many of the inequities that increase people’s risk for undertreated SUD also increase risk for COVID-19 infection, including racism,12 poverty, and homelessness.4 “Stay home and stay safe” is not an option for people who are unsheltered or whose homes are unsafe because of risks of physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Poverty commonly forces people to live in crowded communal apartments or shelters, rely on public transportation, wait in long lines at food pantries, and continue to work, even if unwell. Many shelters have had to reduce the number of people they serve to reduce crowding and support social distancing, which further compounds risks of unstable housing. Unfortunately, the same structural inequities that exacerbate SUD worsen the COVID-19 crisis.13

ROLE FOR HOSPITALISTS

The intersecting vulnerabilities of SUD and COVID-19 heighten an already urgent need to address SUD among hospitalized patients.14 While COVID-19 may increase harms of substance use, it may also increase people’s readiness to engage in treatment given changes to the drug supply and patient’s concerns about health risks. As such, it is even more critical to make treatment readily accessible and support harm reduction. Hospitalists can take important, actionable steps for patients with SUD—many of which are good general practices14 (Appendix Table).

Hospitalists should do the following:

1. Identify and treat acute withdrawal.15

2. Manage acute pain, including providing high-dose opioids if needed.16 Both practices (1 and 2) are evidence-based, can promote patient’s trust in providers,17 and can help avoid patients leaving against medical advice (AMA). Leaving AMA can lead to poor individual health and further threaten public health if patients leave with undiagnosed or unmanaged COVID-19 infection.

3. Encourage their hospitals to provide patients with tablets or other means to communicate with family, friends, and recovery supports via videolink, and refer patients to virtual peer support and recovery meetings during hospitalization.18 These practices may further support patients in tolerating hospitalization and prevent AMA discharge.

4. Initiate medication for addiction during admission and refer to addictions treatment after discharge. COVID-19–related regulatory changes such as expanded telehealth buprenorphine options and fewer daily dosing requirements for methadone may make this easier. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol and tobacco use disorders,15 especially given heightened possibility of unhealthy alcohol use and the respiratory complications associated with both tobacco and COVID-19.

5. Assess mental health and suicide risks19 given their association with social isolation, job loss, and financial insecurity.

6. Discuss relapse prevention among people in recovery.

7. Assess overdose risk and promote harm reduction.19 Specifically, this may include counseling patients to avoid sharing smoking supplies to avoid COVID-19 transmission, identifying places to access clean syringes, prescribing naloxone,20 and providing supports so that, if patients need to use alone, they can do so more safely.21

8. Consider high-risk transitions that may be exacerbated by COVID-19. COVID-19 may make safe discharge plans among people experiencing homelessness very challenging. Some communities are rapidly repurposing existing spaces or building new ones to care for people without a safe place to recover after acute hospitalization, yet many communities have no such resources. Hospital teams should consider the possibility that community services and SUD treatment resources may change rapidly during the pandemic. Hospitals can maintain updated resource lists and consider partnering with state and local health departments to improve safe care for people experiencing homelessness or lacking basic services.

COVID-19 is putting enormous strain on many US hospitals. Hospital-based addictions care is under resourced in the best of times,14 and while some hospitals have addiction consult services, many do not. To what degree hospitalists and hospital teams can address anything beyond COVID-19 emergencies will vary based on settings and resources. Furthermore, we recognize that who performs various activities will depend on individual hospital’s resources and practices. Addiction consult services, if available, can play a critical role, as can hospital social workers and care managers, nurses, residents, students, and other members of the healthcare team.

Finally, though COVID-19 adds tremendous stress to hospitals, permanent improvements in SUD treatment systems such as telephone visits for buprenorphine or eased methadone restrictions may emerge that could reduce barriers to hospital-based addictions care.11 Leveraging these changes now may help hospital providers to better support patients long-term.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization can be a challenging time for patients with SUD and for the hospital teams who care for them. These tensions are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet hospitalists play a critical role in addressing the converging crises of SUD and COVID-19. Providing comprehensive, compassionate, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with SUD is important for both individual and community health during COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr King received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (UG1DA015815) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037441). Dr Snyder received a Public Health Institute grant payable to her institution.

1. Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated health care system. J Addict Med. 2017;11(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000260

2. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424

3. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

4. Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30085-2

5. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

6. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Intersecting U.S. epidemics: COVID-19 and lack of health insurance. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):63-64. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-1491

7. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a ‘risk environment’: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010

8. Harm Reduction Coalition. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://harmreduction.org/

9. COVID-19 and the drug supply chain: from production and trafficking to use. Global Research Network, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020. http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf

10. Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Nikolopoulos GK, Friedman SR. Immediate impact of hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):878-884. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.978675

11. FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf

12. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

13. Baggett TP, Lewis E, Gaeta JM. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness: early evidence from Boston. Ann Fam Med. Preprint posted April 4, 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/154734

14. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

15. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001

16. Quality & Science. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://www.asam.org/Quality-Science/quality

17. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. Published online December 12, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

18. Digital Recovery Support Services. Recovery Link. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://myrecoverylink.com/digital-recovery-support/

19. Publications and Digital Products: Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage for Clinicians. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. September 2009. Accessed April 4, 2020. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAFE-T-Pocket-Card-Suicide-Assessment-Five-Step-Evaluation-and-Triage-for-Clinicians/sma09-4432

20. Prescribe to Prevent: Prescribe Naloxone, Save a Life. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://prescribetoprevent.org/

21. Never Use Alone. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://neverusealone.com/

1. Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated health care system. J Addict Med. 2017;11(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000260

2. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424

3. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

4. Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30085-2

5. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

6. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Intersecting U.S. epidemics: COVID-19 and lack of health insurance. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):63-64. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-1491

7. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a ‘risk environment’: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010

8. Harm Reduction Coalition. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://harmreduction.org/

9. COVID-19 and the drug supply chain: from production and trafficking to use. Global Research Network, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020. http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf

10. Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Nikolopoulos GK, Friedman SR. Immediate impact of hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):878-884. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.978675

11. FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf

12. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

13. Baggett TP, Lewis E, Gaeta JM. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness: early evidence from Boston. Ann Fam Med. Preprint posted April 4, 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/154734

14. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

15. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001

16. Quality & Science. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://www.asam.org/Quality-Science/quality

17. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. Published online December 12, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

18. Digital Recovery Support Services. Recovery Link. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://myrecoverylink.com/digital-recovery-support/

19. Publications and Digital Products: Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage for Clinicians. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. September 2009. Accessed April 4, 2020. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAFE-T-Pocket-Card-Suicide-Assessment-Five-Step-Evaluation-and-Triage-for-Clinicians/sma09-4432

20. Prescribe to Prevent: Prescribe Naloxone, Save a Life. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://prescribetoprevent.org/

21. Never Use Alone. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://neverusealone.com/

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Leadership & Professional Development: Engaging Patients as Stakeholders

“Nothing about us without us” (Latin: ”Nihil de nobis, sine nobis”)

Hospitalists are at the forefront of decisions, innovations, and system-improvement projects that impact hospitalized patients. However, many of our decisions—while centered on patient care—fail to include their perspectives or views.

In his book Total Leadership, Stewart Friedman describes the importance of identifying and engaging key stakeholders.1 Friedman exhorts leaders to engage stakeholders in conversations to “confirm or correct your current understanding of stakeholder expectations.” In other words, instead of assuming what stakeholders want, ask and verify before proceeding.

Although hospitalists frequently include stakeholders such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists in system-improvement initiatives, engaging patients is less common.

Why do we omit patients as stakeholders? There are considerable barriers to seeking patient input. The busy hospital environment or the acuity of a patient’s illness may, for instance, limit engagement between hospital caregivers and patients. Further, the power imbalance between physicians and patients may make it uncomfortable for the patient to offer direct feedback.

However, the importance of patient input is increasingly recognized by researchers. For example, community-based participatory research “involves community members or recipients of interventions in all phases of the research process.”2 Similarly, we believe hospitalists should engage patients when designing new clinical initiatives.

Examples from some institutions provide further support of this concept. The Dana Farber Cancer Institute created a patient and family advisory council in response to the loss of trust over errors and in the face of community outrage over an impending joint venture. While the scope was initially limited to the collection of feedback regarding patient satisfaction and preferences, the council evolved to become an integral part of organizational decision making. Patient contributions were subsequently assimilated into policies, continuous improvement teams, and even search committees. Additional benefits included patient-generated initiatives such as “patient rounds.”3 Specifically soliciting input from hospitalized patients to inform hospital-based interventions may be uncommon, but this practice holds the potential to yield vital insights.4

We have experienced this benefit at our institution. For example, before implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consult service, we asked hospitalized patients struggling with addiction about their needs. The patient voice highlighted a lack of trust for hospital providers and led directly to the inclusion of peer-recovery mentors as part of the consulting team.5

Many organizations, including our own, have instituted a patient/family advisory committee comprising former patients and family members who participate voluntarily in projects and provide input. This resource can serve as an excellent platform for patient involvement. At the University of Michigan, the patient and family advisory council provides input on every major institutional decision, from the construction of a new building to the introduction of a new clinical service. This “hardwired” practice ensures that patients’ voices and views are incorporated into major health system decisions.

In order to engage patients as stakeholders, we recommend: (1) Be sensitive to the power imbalance between clinicians and patients and recognize that hospitalized patients may not feel comfortable providing direct feedback. (2) Familiarize yourself with your institution’s patient/family advisory committee. If one does not exist, consider soliciting responses from patients via interviews and/or postdischarge surveys. (3) Deliberately seek the opinions, experience, and values of patients or their representatives. (4) For projects aimed at improving patient experience, include patients among your key stakeholders.

Involving patients as stakeholders requires effort; however, it has potential to reap valuable rewards, making healthcare improvements more effective, inclusive, and healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey S. Stewart for his contributions and feedback on this topic and manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Friedman S. Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life (With New Preface). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

2. Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti034

3. Ponte PR, Conlin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care come alive: achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(2):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200302000-00004

4. O’Leary KJ, Chapman MM, Foster S, O’Hara L, Henschen BL, Cameron KA. Frequently hospitalized patients’ perceptions of factors contributing to high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(9):521-526. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3175

5. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

“Nothing about us without us” (Latin: ”Nihil de nobis, sine nobis”)

Hospitalists are at the forefront of decisions, innovations, and system-improvement projects that impact hospitalized patients. However, many of our decisions—while centered on patient care—fail to include their perspectives or views.

In his book Total Leadership, Stewart Friedman describes the importance of identifying and engaging key stakeholders.1 Friedman exhorts leaders to engage stakeholders in conversations to “confirm or correct your current understanding of stakeholder expectations.” In other words, instead of assuming what stakeholders want, ask and verify before proceeding.

Although hospitalists frequently include stakeholders such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists in system-improvement initiatives, engaging patients is less common.

Why do we omit patients as stakeholders? There are considerable barriers to seeking patient input. The busy hospital environment or the acuity of a patient’s illness may, for instance, limit engagement between hospital caregivers and patients. Further, the power imbalance between physicians and patients may make it uncomfortable for the patient to offer direct feedback.

However, the importance of patient input is increasingly recognized by researchers. For example, community-based participatory research “involves community members or recipients of interventions in all phases of the research process.”2 Similarly, we believe hospitalists should engage patients when designing new clinical initiatives.

Examples from some institutions provide further support of this concept. The Dana Farber Cancer Institute created a patient and family advisory council in response to the loss of trust over errors and in the face of community outrage over an impending joint venture. While the scope was initially limited to the collection of feedback regarding patient satisfaction and preferences, the council evolved to become an integral part of organizational decision making. Patient contributions were subsequently assimilated into policies, continuous improvement teams, and even search committees. Additional benefits included patient-generated initiatives such as “patient rounds.”3 Specifically soliciting input from hospitalized patients to inform hospital-based interventions may be uncommon, but this practice holds the potential to yield vital insights.4

We have experienced this benefit at our institution. For example, before implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consult service, we asked hospitalized patients struggling with addiction about their needs. The patient voice highlighted a lack of trust for hospital providers and led directly to the inclusion of peer-recovery mentors as part of the consulting team.5

Many organizations, including our own, have instituted a patient/family advisory committee comprising former patients and family members who participate voluntarily in projects and provide input. This resource can serve as an excellent platform for patient involvement. At the University of Michigan, the patient and family advisory council provides input on every major institutional decision, from the construction of a new building to the introduction of a new clinical service. This “hardwired” practice ensures that patients’ voices and views are incorporated into major health system decisions.

In order to engage patients as stakeholders, we recommend: (1) Be sensitive to the power imbalance between clinicians and patients and recognize that hospitalized patients may not feel comfortable providing direct feedback. (2) Familiarize yourself with your institution’s patient/family advisory committee. If one does not exist, consider soliciting responses from patients via interviews and/or postdischarge surveys. (3) Deliberately seek the opinions, experience, and values of patients or their representatives. (4) For projects aimed at improving patient experience, include patients among your key stakeholders.

Involving patients as stakeholders requires effort; however, it has potential to reap valuable rewards, making healthcare improvements more effective, inclusive, and healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey S. Stewart for his contributions and feedback on this topic and manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

“Nothing about us without us” (Latin: ”Nihil de nobis, sine nobis”)

Hospitalists are at the forefront of decisions, innovations, and system-improvement projects that impact hospitalized patients. However, many of our decisions—while centered on patient care—fail to include their perspectives or views.

In his book Total Leadership, Stewart Friedman describes the importance of identifying and engaging key stakeholders.1 Friedman exhorts leaders to engage stakeholders in conversations to “confirm or correct your current understanding of stakeholder expectations.” In other words, instead of assuming what stakeholders want, ask and verify before proceeding.

Although hospitalists frequently include stakeholders such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists in system-improvement initiatives, engaging patients is less common.

Why do we omit patients as stakeholders? There are considerable barriers to seeking patient input. The busy hospital environment or the acuity of a patient’s illness may, for instance, limit engagement between hospital caregivers and patients. Further, the power imbalance between physicians and patients may make it uncomfortable for the patient to offer direct feedback.

However, the importance of patient input is increasingly recognized by researchers. For example, community-based participatory research “involves community members or recipients of interventions in all phases of the research process.”2 Similarly, we believe hospitalists should engage patients when designing new clinical initiatives.

Examples from some institutions provide further support of this concept. The Dana Farber Cancer Institute created a patient and family advisory council in response to the loss of trust over errors and in the face of community outrage over an impending joint venture. While the scope was initially limited to the collection of feedback regarding patient satisfaction and preferences, the council evolved to become an integral part of organizational decision making. Patient contributions were subsequently assimilated into policies, continuous improvement teams, and even search committees. Additional benefits included patient-generated initiatives such as “patient rounds.”3 Specifically soliciting input from hospitalized patients to inform hospital-based interventions may be uncommon, but this practice holds the potential to yield vital insights.4

We have experienced this benefit at our institution. For example, before implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consult service, we asked hospitalized patients struggling with addiction about their needs. The patient voice highlighted a lack of trust for hospital providers and led directly to the inclusion of peer-recovery mentors as part of the consulting team.5

Many organizations, including our own, have instituted a patient/family advisory committee comprising former patients and family members who participate voluntarily in projects and provide input. This resource can serve as an excellent platform for patient involvement. At the University of Michigan, the patient and family advisory council provides input on every major institutional decision, from the construction of a new building to the introduction of a new clinical service. This “hardwired” practice ensures that patients’ voices and views are incorporated into major health system decisions.

In order to engage patients as stakeholders, we recommend: (1) Be sensitive to the power imbalance between clinicians and patients and recognize that hospitalized patients may not feel comfortable providing direct feedback. (2) Familiarize yourself with your institution’s patient/family advisory committee. If one does not exist, consider soliciting responses from patients via interviews and/or postdischarge surveys. (3) Deliberately seek the opinions, experience, and values of patients or their representatives. (4) For projects aimed at improving patient experience, include patients among your key stakeholders.

Involving patients as stakeholders requires effort; however, it has potential to reap valuable rewards, making healthcare improvements more effective, inclusive, and healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey S. Stewart for his contributions and feedback on this topic and manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Friedman S. Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life (With New Preface). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

2. Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti034

3. Ponte PR, Conlin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care come alive: achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(2):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200302000-00004

4. O’Leary KJ, Chapman MM, Foster S, O’Hara L, Henschen BL, Cameron KA. Frequently hospitalized patients’ perceptions of factors contributing to high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(9):521-526. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3175

5. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

1. Friedman S. Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life (With New Preface). Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

2. Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti034

3. Ponte PR, Conlin G, Conway JB, et al. Making patient-centered care come alive: achieving full integration of the patient’s perspective. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(2):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200302000-00004

4. O’Leary KJ, Chapman MM, Foster S, O’Hara L, Henschen BL, Cameron KA. Frequently hospitalized patients’ perceptions of factors contributing to high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(9):521-526. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3175

5. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Call to Action: Hospitalists’ Role in Addressing Substance Use Disorder

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

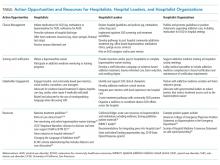

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.

1. Weiss A, Elixhauser A, Barrett M, Steiner C, Bailey M, O’Malley L. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009-2014. Statistical Brief #219. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp. Accessed May 21, 2019.

2. Winkelman TA, Admon LK, Jennings L, Shippee ND, Richardson CR, Bart G. Evaluation of amphetamine-related hospitalizations and associated clinical outcomes and costs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183758. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3758.

3. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424.

4. Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addict Med. 2012;6(1):50-56. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51.

5. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736.

6. Velez C, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis P, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. doi 10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4.

7. Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909-916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z.

8. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993.

9. McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD005191 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005191.pub3.

10. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496.

11. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001.

12. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010.

13. Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019. pii: S0955-3959(19)30018-0. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010.

14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder-Executive Summary. February 2018. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Executive-Summary/sma18-5063exsumm. Accessed August 8, 2019.

15. Providers Clinical Support System. Discover the rewards of treating patients with Opioid Use Disorders. https://pcssnow.org/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

16. California Bridge Program. Treatment Starts Here: Resources for the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders from the Acute Care Setting. https://www.bridgetotreatment.org/resources. Accessed August 7, 2019.