User login

Things We Do for No Reason™: Prescribing Thiamine, Folate and Multivitamins on Discharge for Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is admitted with decompensated heart failure and experiences alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization. He improves with guideline-directed heart failure therapy and benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Discharge medications are metoprolol succinate, lisinopril, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin, thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin. No medications are offered for AUD treatment. At follow-up a week later, he presents with dyspnea and reports poor medication adherence and a return to heavy drinking.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IT IS HELPFUL TO PRESCRIBE VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION TO PATIENTS WITH AUD AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

AUD is common among hospitalized patients.1 AUD increases the risk of vitamin deficiencies due to the toxic effects of alcohol on the gastrointestinal tract and liver, causing impaired digestion, reduced absorption, and increased degradation of key micronutrients.2,3 Other risk factors for AUD-associated vitamin deficiencies include food insecurity and the replacement of nutrient-rich food with alcohol. Since the body does not readily store water-soluble vitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9), people require regular dietary replenishment of these nutrients. Thus, if individuals with AUD eat less fortified food, they risk developing thiamine, folate, niacin, and other vitamin deficiencies. Since AUD puts patients at risk for vitamin deficiencies, hospitalized patients typically receive vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin (most formulations contain water-soluble vitamins B and C and micronutrients).1 Hospitalists often continue these medications at discharge.

Thiamine deficiency may manifest as Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), peripheral neuropathy, or a high-output heart failure state.

Hospitalists empirically treat with thiamine, folate, and other vitamins upon hospital admission with the intent of reducing morbidity associated with nutritional deficiencies.1 Repletion poses few risks to patients since the kidneys eliminate water-soluble vitamins. Multivitamins also have a low potential for direct harm and a low cost. Given the consequences of missing a deficiency, alcohol withdrawal–management order sets commonly embed vitamin repletion orders.6

WHY ROUTINELY PRESCRIBING VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH AUD IS A TWDFNR

Hospitalists often reflexively continue vitamin supplementation on discharge. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that prescribing vitamin supplementation leads to clinically significant improvements for people with AUD, and patients can experience harms.

Literature and specialty guidelines lack consensus on rational vitamin supplementation in patients with AUD.2,7,8 Folate testing is not recommended due to inaccuracies.9 In fact, clinical data, such as body mass index, more accurately predict alcohol-related cognitive impairment than blood levels of vitamins.10 In one small study of vitamin deficiencies among patients with acute alcohol intoxication, none had low B12 or folate levels.11 A systematic review among people experiencing homelessness with unhealthy alcohol use showed no clear pattern of vitamin deficiencies across studies, although vitamin C and thiamine deficiencies predominated.12

In the absence of reliable thiamine and folate testing to confirm deficiencies, clinicians must use their clinical assessment skills. Clinicians rarely evaluate patients with AUD for vitamin deficiency risk factors and instead reflexively prescribe vitamin supplementation. An AUD diagnosis may serve as a sensitive, but not specific, risk factor for those in need of vitamin supplementation.

Other limitations make prescribing oral vitamins reflexively at discharge a low-value practice. Thiamine, often prescribed orally in the hospital and on discharge, has poor oral bioavailability.13 Unfortunately, people with AUD have decreased and variable thiamine absorption. To prevent WE, thiamine must cross the blood-brain barrier, and the literature provides insufficient evidence to guide clinicians on an appropriate oral thiamine dose, frequency, or duration of treatment.14 While early high-dose IV thiamine may treat or prevent WE during hospitalization, low-dose oral thiamine may not provide benefit to patients with AUD.5

The literature also provides sparse evidence for folate supplementation and its optimal dose. Since 1998, when the United States mandated fortifying grain products with folic acid, people rarely have low serum folate levels. Though patients with AUD have lower folate levels relative to the general population,15 this difference does not seem clinically significant. While limited data show an association between oral multivitamin supplementation and improved serum nutrient levels among people with AUD, we lack evidence on clinical outcomes.16

Most importantly, for a practice lacking strong evidence, prescribing multiple vitamins at discharge may result in harm from polypharmacy and unnecessary costs for the recently hospitalized patient. Alcohol use is associated with decreased adherence to medications for chronic conditions,17 including HIV, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and psychiatric diseases. In addition, research shows an association between an increased number of discharge medications and higher risk for hospital readmission. The harm may actually correlate with the number of medications and complexity of the regimen rather than the risk profile of the medications themselves.18 Providers underestimate the impact of adding multiple vitamins at discharge, especially for patients who have several co-occurring medical conditions that require other medications. Furthermore, insurance rarely covers vitamins, leading hospitals or patients to incur the costs at discharge.

WHEN TO CONSIDER VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT DISCHARGE FOR PATIENTS WITH AUD

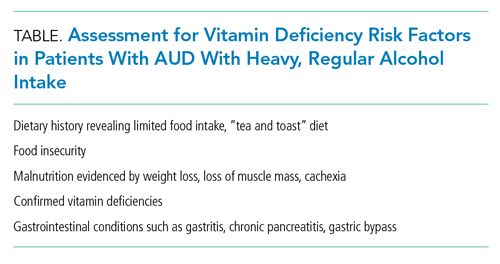

When treating patients with AUD, consider the potential benefit of vitamin supplementation for the individual. If a patient with regular, heavy alcohol use is at high risk of vitamin deficiencies due to ongoing risk factors (Table), hospitalists should discuss vitamin therapy via a patient-centered risk-benefit process.

When considering discharge vitamins, make concurrent efforts to enhance patient nutrition via decreased alcohol consumption and improved healthy food intake. While some patients do not have a goal of abstaining from alcohol, providing resources to food access may help decrease the harms of drinking. Education may help patients learn that vitamin deficiencies can result from heavy alcohol use.

Multivitamin formulations have variable doses of vitamins but can contain 100% or more of the daily value of thiamine and folic acid. For patients with AUD at lower risk of vitamin deficiencies (ie, mild alcohol use disorder with a healthy diet), discuss risks and benefits of supplementation. If they desire supplementation, a single thiamine-containing vitamin alone may be highest yield since it is the most morbid vitamin deficiency. Conversely, a patient with heavy alcohol intake and other risk factors for malnutrition may benefit from a higher dose of supplementation, achieved by prescribing a multivitamin alongside additional doses of thiamine and folate. However, the literature lacks evidence to guide clinicians on optimal vitamin dosing and formulations.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of reflexively prescribing thiamine, folate, and multivitamin, clinicians can assess patients for AUD, provide motivational interviewing, and offer AUD treatment. Hospitalists should initiate and prescribe evidence-based medications for AUD for patients interested in reducing or stopping their alcohol intake. We can choose from Food and Drug Administration–approved AUD medications, including naltrexone and acamprosate. Unfortunately, less than 3% of patients with AUD receive medication therapy.19 Our healthcare systems can also refer individuals to community psychosocial treatment.

For patients with risk factors, prescribe empiric IV thiamine during hospitalization. Clinicians should then perform a risk-benefit assessment rather than reflexively prescribe vitamins to patients with AUD at discharge. We should also counsel patients to eat food when drinking to decrease alcohol-related harms.20 Patients experiencing food insecurity should be linked to food resources through inpatient nutritional and social work consultations.

Elicit patient preference around vitamin supplementation after discharge. For patients with AUD who desire supplementation without risk factors for malnutrition (Table), consider prescribing a single thiamine-containing vitamin for prevention of thiamine deficiency, which, unlike other vitamin deficiencies, has the potential to be irreversible and life-threatening. Though no evidence currently supports this practice, it stands to reason that prescribing a single tablet could decrease the number of pills for patients who struggle with pill burden.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Offer evidence-based medication treatment for AUD.

- Connect patients experiencing food insecurity with appropriate resources.

- For patients initiated on a multivitamin, folate, and high-dose IV thiamine at admission, perform vitamin de-escalation during hospitalization.

- Risk-stratify hospitalized patients with AUD for additional risk factors for vitamin deficiencies (Table). In those with additional risk factors, offer supplementation if consistent with patient preference. Balance the benefits of vitamin supplementation with the risks of polypharmacy, particularly if the patient has conditions requiring multiple medications.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our case, the hospitalist initiates IV thiamine, folate, and a multivitamin at admission and assesses the patient’s nutritional status and food insecurity. The hospitalist deems the patient—who eats regular, balanced meals—to be at low risk for vitamin deficiencies. The medical team discontinues folate and multivitamins before discharge and continues IV thiamine throughout the 3-day hospitalization. The patient and clinician agree that unaddressed AUD played a key role in the patient’s heart failure exacerbation. The clinician elicits the patient’s goals around their alcohol use, discusses AUD treatment, and initiates naltrexone for AUD.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

1. Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-8-11

2. Lewis MJ. Alcoholism and nutrition: a review of vitamin supplementation and treatment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23(2):138-144. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000622

3. Bergmans RS, Coughlin L, Wilson T, Malecki K. Cross-sectional associations of food insecurity with smoking cigarettes and heavy alcohol use in a population-based sample of adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107646

4. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):911-915. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12522

5. Flannery AH, Adkins DA, Cook AM. Unpeeling the evidence for the banana bag: evidence-based recommendations for the management of alcohol-associated vitamin and electrolyte deficiencies in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1545-1552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000001659

6. Wai JM, Aloezos C, Mowrey WB, Baron SW, Cregin R, Forman HL. Using clinical decision support through the electronic medical record to increase prescribing of high-dose parenteral thiamine in hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:117-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.017

7. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. January 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/quality-science/the_asam_clinical_practice_guideline_on_alcohol-1.pdf?sfvrsn=ba255c2_2

8. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):307-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23258

9. Breu AC, Theisen-Toupal J, Feldman LS. Serum and red blood cell folate testing on hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):753-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2385

10. Gautron M-A, Questel F, Lejoyeux M, Bellivier F, Vorspan F. Nutritional status during inpatient alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(1):64-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx086

11. Li SF, Jacob J, Feng J, Kulkarni M. Vitamin deficiencies in acutely intoxicated patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(7):792-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.003

12. Ijaz S, Jackson J, Thorley H, et al. Nutritional deficiencies in homeless persons with problematic drinking: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0564-4

13. Day GS, Ladak S, Curley K, et al. Thiamine prescribing practices within university-affiliated hospitals: a multicenter retrospective review. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):246-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2324

14. Day E, Bentham PW, Callaghan R, Kuruvilla T, George S. Thiamine for prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in people who abuse alcohol. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(7):CD004033. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004033.pub3

15. Medici V, Halsted CH. Folate, alcohol, and liver disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(4):596-606. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200077

16. Ijaz S, Thorley H, Porter K, et al. Interventions for preventing or treating malnutrition in homeless problem-drinkers: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0722-3

17. Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(11):795-803. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004

18. Picker D, Heard K, Bailey TC, Martin NR, LaRossa GN, Kollef MH. The number of discharge medications predicts thirty-day hospital readmission: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0950-9

19. Han B, Jones CM, Einstein EB, Powell PA, Compton WM. Use of medications for alcohol use disorder in the US: results From the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(8):922–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1271

20. Collins SE, Duncan MH, Saxon AJ, et al. Combining behavioral harm-reduction treatment and extended-release naltrexone for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorder in the USA: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):287-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30489-2

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is admitted with decompensated heart failure and experiences alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization. He improves with guideline-directed heart failure therapy and benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Discharge medications are metoprolol succinate, lisinopril, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin, thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin. No medications are offered for AUD treatment. At follow-up a week later, he presents with dyspnea and reports poor medication adherence and a return to heavy drinking.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IT IS HELPFUL TO PRESCRIBE VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION TO PATIENTS WITH AUD AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

AUD is common among hospitalized patients.1 AUD increases the risk of vitamin deficiencies due to the toxic effects of alcohol on the gastrointestinal tract and liver, causing impaired digestion, reduced absorption, and increased degradation of key micronutrients.2,3 Other risk factors for AUD-associated vitamin deficiencies include food insecurity and the replacement of nutrient-rich food with alcohol. Since the body does not readily store water-soluble vitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9), people require regular dietary replenishment of these nutrients. Thus, if individuals with AUD eat less fortified food, they risk developing thiamine, folate, niacin, and other vitamin deficiencies. Since AUD puts patients at risk for vitamin deficiencies, hospitalized patients typically receive vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin (most formulations contain water-soluble vitamins B and C and micronutrients).1 Hospitalists often continue these medications at discharge.

Thiamine deficiency may manifest as Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), peripheral neuropathy, or a high-output heart failure state.

Hospitalists empirically treat with thiamine, folate, and other vitamins upon hospital admission with the intent of reducing morbidity associated with nutritional deficiencies.1 Repletion poses few risks to patients since the kidneys eliminate water-soluble vitamins. Multivitamins also have a low potential for direct harm and a low cost. Given the consequences of missing a deficiency, alcohol withdrawal–management order sets commonly embed vitamin repletion orders.6

WHY ROUTINELY PRESCRIBING VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH AUD IS A TWDFNR

Hospitalists often reflexively continue vitamin supplementation on discharge. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that prescribing vitamin supplementation leads to clinically significant improvements for people with AUD, and patients can experience harms.

Literature and specialty guidelines lack consensus on rational vitamin supplementation in patients with AUD.2,7,8 Folate testing is not recommended due to inaccuracies.9 In fact, clinical data, such as body mass index, more accurately predict alcohol-related cognitive impairment than blood levels of vitamins.10 In one small study of vitamin deficiencies among patients with acute alcohol intoxication, none had low B12 or folate levels.11 A systematic review among people experiencing homelessness with unhealthy alcohol use showed no clear pattern of vitamin deficiencies across studies, although vitamin C and thiamine deficiencies predominated.12

In the absence of reliable thiamine and folate testing to confirm deficiencies, clinicians must use their clinical assessment skills. Clinicians rarely evaluate patients with AUD for vitamin deficiency risk factors and instead reflexively prescribe vitamin supplementation. An AUD diagnosis may serve as a sensitive, but not specific, risk factor for those in need of vitamin supplementation.

Other limitations make prescribing oral vitamins reflexively at discharge a low-value practice. Thiamine, often prescribed orally in the hospital and on discharge, has poor oral bioavailability.13 Unfortunately, people with AUD have decreased and variable thiamine absorption. To prevent WE, thiamine must cross the blood-brain barrier, and the literature provides insufficient evidence to guide clinicians on an appropriate oral thiamine dose, frequency, or duration of treatment.14 While early high-dose IV thiamine may treat or prevent WE during hospitalization, low-dose oral thiamine may not provide benefit to patients with AUD.5

The literature also provides sparse evidence for folate supplementation and its optimal dose. Since 1998, when the United States mandated fortifying grain products with folic acid, people rarely have low serum folate levels. Though patients with AUD have lower folate levels relative to the general population,15 this difference does not seem clinically significant. While limited data show an association between oral multivitamin supplementation and improved serum nutrient levels among people with AUD, we lack evidence on clinical outcomes.16

Most importantly, for a practice lacking strong evidence, prescribing multiple vitamins at discharge may result in harm from polypharmacy and unnecessary costs for the recently hospitalized patient. Alcohol use is associated with decreased adherence to medications for chronic conditions,17 including HIV, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and psychiatric diseases. In addition, research shows an association between an increased number of discharge medications and higher risk for hospital readmission. The harm may actually correlate with the number of medications and complexity of the regimen rather than the risk profile of the medications themselves.18 Providers underestimate the impact of adding multiple vitamins at discharge, especially for patients who have several co-occurring medical conditions that require other medications. Furthermore, insurance rarely covers vitamins, leading hospitals or patients to incur the costs at discharge.

WHEN TO CONSIDER VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT DISCHARGE FOR PATIENTS WITH AUD

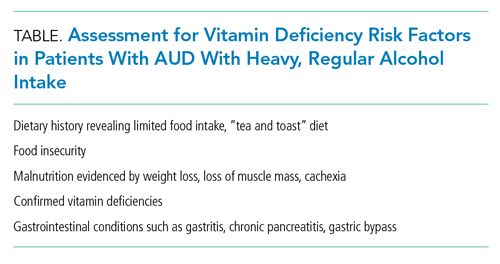

When treating patients with AUD, consider the potential benefit of vitamin supplementation for the individual. If a patient with regular, heavy alcohol use is at high risk of vitamin deficiencies due to ongoing risk factors (Table), hospitalists should discuss vitamin therapy via a patient-centered risk-benefit process.

When considering discharge vitamins, make concurrent efforts to enhance patient nutrition via decreased alcohol consumption and improved healthy food intake. While some patients do not have a goal of abstaining from alcohol, providing resources to food access may help decrease the harms of drinking. Education may help patients learn that vitamin deficiencies can result from heavy alcohol use.

Multivitamin formulations have variable doses of vitamins but can contain 100% or more of the daily value of thiamine and folic acid. For patients with AUD at lower risk of vitamin deficiencies (ie, mild alcohol use disorder with a healthy diet), discuss risks and benefits of supplementation. If they desire supplementation, a single thiamine-containing vitamin alone may be highest yield since it is the most morbid vitamin deficiency. Conversely, a patient with heavy alcohol intake and other risk factors for malnutrition may benefit from a higher dose of supplementation, achieved by prescribing a multivitamin alongside additional doses of thiamine and folate. However, the literature lacks evidence to guide clinicians on optimal vitamin dosing and formulations.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of reflexively prescribing thiamine, folate, and multivitamin, clinicians can assess patients for AUD, provide motivational interviewing, and offer AUD treatment. Hospitalists should initiate and prescribe evidence-based medications for AUD for patients interested in reducing or stopping their alcohol intake. We can choose from Food and Drug Administration–approved AUD medications, including naltrexone and acamprosate. Unfortunately, less than 3% of patients with AUD receive medication therapy.19 Our healthcare systems can also refer individuals to community psychosocial treatment.

For patients with risk factors, prescribe empiric IV thiamine during hospitalization. Clinicians should then perform a risk-benefit assessment rather than reflexively prescribe vitamins to patients with AUD at discharge. We should also counsel patients to eat food when drinking to decrease alcohol-related harms.20 Patients experiencing food insecurity should be linked to food resources through inpatient nutritional and social work consultations.

Elicit patient preference around vitamin supplementation after discharge. For patients with AUD who desire supplementation without risk factors for malnutrition (Table), consider prescribing a single thiamine-containing vitamin for prevention of thiamine deficiency, which, unlike other vitamin deficiencies, has the potential to be irreversible and life-threatening. Though no evidence currently supports this practice, it stands to reason that prescribing a single tablet could decrease the number of pills for patients who struggle with pill burden.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Offer evidence-based medication treatment for AUD.

- Connect patients experiencing food insecurity with appropriate resources.

- For patients initiated on a multivitamin, folate, and high-dose IV thiamine at admission, perform vitamin de-escalation during hospitalization.

- Risk-stratify hospitalized patients with AUD for additional risk factors for vitamin deficiencies (Table). In those with additional risk factors, offer supplementation if consistent with patient preference. Balance the benefits of vitamin supplementation with the risks of polypharmacy, particularly if the patient has conditions requiring multiple medications.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our case, the hospitalist initiates IV thiamine, folate, and a multivitamin at admission and assesses the patient’s nutritional status and food insecurity. The hospitalist deems the patient—who eats regular, balanced meals—to be at low risk for vitamin deficiencies. The medical team discontinues folate and multivitamins before discharge and continues IV thiamine throughout the 3-day hospitalization. The patient and clinician agree that unaddressed AUD played a key role in the patient’s heart failure exacerbation. The clinician elicits the patient’s goals around their alcohol use, discusses AUD treatment, and initiates naltrexone for AUD.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is admitted with decompensated heart failure and experiences alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization. He improves with guideline-directed heart failure therapy and benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Discharge medications are metoprolol succinate, lisinopril, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin, thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin. No medications are offered for AUD treatment. At follow-up a week later, he presents with dyspnea and reports poor medication adherence and a return to heavy drinking.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK IT IS HELPFUL TO PRESCRIBE VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION TO PATIENTS WITH AUD AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

AUD is common among hospitalized patients.1 AUD increases the risk of vitamin deficiencies due to the toxic effects of alcohol on the gastrointestinal tract and liver, causing impaired digestion, reduced absorption, and increased degradation of key micronutrients.2,3 Other risk factors for AUD-associated vitamin deficiencies include food insecurity and the replacement of nutrient-rich food with alcohol. Since the body does not readily store water-soluble vitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9), people require regular dietary replenishment of these nutrients. Thus, if individuals with AUD eat less fortified food, they risk developing thiamine, folate, niacin, and other vitamin deficiencies. Since AUD puts patients at risk for vitamin deficiencies, hospitalized patients typically receive vitamin supplementation, including thiamine, folic acid, and a multivitamin (most formulations contain water-soluble vitamins B and C and micronutrients).1 Hospitalists often continue these medications at discharge.

Thiamine deficiency may manifest as Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), peripheral neuropathy, or a high-output heart failure state.

Hospitalists empirically treat with thiamine, folate, and other vitamins upon hospital admission with the intent of reducing morbidity associated with nutritional deficiencies.1 Repletion poses few risks to patients since the kidneys eliminate water-soluble vitamins. Multivitamins also have a low potential for direct harm and a low cost. Given the consequences of missing a deficiency, alcohol withdrawal–management order sets commonly embed vitamin repletion orders.6

WHY ROUTINELY PRESCRIBING VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH AUD IS A TWDFNR

Hospitalists often reflexively continue vitamin supplementation on discharge. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that prescribing vitamin supplementation leads to clinically significant improvements for people with AUD, and patients can experience harms.

Literature and specialty guidelines lack consensus on rational vitamin supplementation in patients with AUD.2,7,8 Folate testing is not recommended due to inaccuracies.9 In fact, clinical data, such as body mass index, more accurately predict alcohol-related cognitive impairment than blood levels of vitamins.10 In one small study of vitamin deficiencies among patients with acute alcohol intoxication, none had low B12 or folate levels.11 A systematic review among people experiencing homelessness with unhealthy alcohol use showed no clear pattern of vitamin deficiencies across studies, although vitamin C and thiamine deficiencies predominated.12

In the absence of reliable thiamine and folate testing to confirm deficiencies, clinicians must use their clinical assessment skills. Clinicians rarely evaluate patients with AUD for vitamin deficiency risk factors and instead reflexively prescribe vitamin supplementation. An AUD diagnosis may serve as a sensitive, but not specific, risk factor for those in need of vitamin supplementation.

Other limitations make prescribing oral vitamins reflexively at discharge a low-value practice. Thiamine, often prescribed orally in the hospital and on discharge, has poor oral bioavailability.13 Unfortunately, people with AUD have decreased and variable thiamine absorption. To prevent WE, thiamine must cross the blood-brain barrier, and the literature provides insufficient evidence to guide clinicians on an appropriate oral thiamine dose, frequency, or duration of treatment.14 While early high-dose IV thiamine may treat or prevent WE during hospitalization, low-dose oral thiamine may not provide benefit to patients with AUD.5

The literature also provides sparse evidence for folate supplementation and its optimal dose. Since 1998, when the United States mandated fortifying grain products with folic acid, people rarely have low serum folate levels. Though patients with AUD have lower folate levels relative to the general population,15 this difference does not seem clinically significant. While limited data show an association between oral multivitamin supplementation and improved serum nutrient levels among people with AUD, we lack evidence on clinical outcomes.16

Most importantly, for a practice lacking strong evidence, prescribing multiple vitamins at discharge may result in harm from polypharmacy and unnecessary costs for the recently hospitalized patient. Alcohol use is associated with decreased adherence to medications for chronic conditions,17 including HIV, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and psychiatric diseases. In addition, research shows an association between an increased number of discharge medications and higher risk for hospital readmission. The harm may actually correlate with the number of medications and complexity of the regimen rather than the risk profile of the medications themselves.18 Providers underestimate the impact of adding multiple vitamins at discharge, especially for patients who have several co-occurring medical conditions that require other medications. Furthermore, insurance rarely covers vitamins, leading hospitals or patients to incur the costs at discharge.

WHEN TO CONSIDER VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION AT DISCHARGE FOR PATIENTS WITH AUD

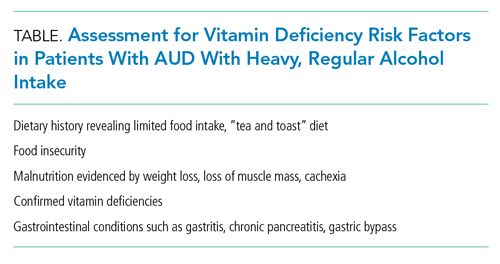

When treating patients with AUD, consider the potential benefit of vitamin supplementation for the individual. If a patient with regular, heavy alcohol use is at high risk of vitamin deficiencies due to ongoing risk factors (Table), hospitalists should discuss vitamin therapy via a patient-centered risk-benefit process.

When considering discharge vitamins, make concurrent efforts to enhance patient nutrition via decreased alcohol consumption and improved healthy food intake. While some patients do not have a goal of abstaining from alcohol, providing resources to food access may help decrease the harms of drinking. Education may help patients learn that vitamin deficiencies can result from heavy alcohol use.

Multivitamin formulations have variable doses of vitamins but can contain 100% or more of the daily value of thiamine and folic acid. For patients with AUD at lower risk of vitamin deficiencies (ie, mild alcohol use disorder with a healthy diet), discuss risks and benefits of supplementation. If they desire supplementation, a single thiamine-containing vitamin alone may be highest yield since it is the most morbid vitamin deficiency. Conversely, a patient with heavy alcohol intake and other risk factors for malnutrition may benefit from a higher dose of supplementation, achieved by prescribing a multivitamin alongside additional doses of thiamine and folate. However, the literature lacks evidence to guide clinicians on optimal vitamin dosing and formulations.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of reflexively prescribing thiamine, folate, and multivitamin, clinicians can assess patients for AUD, provide motivational interviewing, and offer AUD treatment. Hospitalists should initiate and prescribe evidence-based medications for AUD for patients interested in reducing or stopping their alcohol intake. We can choose from Food and Drug Administration–approved AUD medications, including naltrexone and acamprosate. Unfortunately, less than 3% of patients with AUD receive medication therapy.19 Our healthcare systems can also refer individuals to community psychosocial treatment.

For patients with risk factors, prescribe empiric IV thiamine during hospitalization. Clinicians should then perform a risk-benefit assessment rather than reflexively prescribe vitamins to patients with AUD at discharge. We should also counsel patients to eat food when drinking to decrease alcohol-related harms.20 Patients experiencing food insecurity should be linked to food resources through inpatient nutritional and social work consultations.

Elicit patient preference around vitamin supplementation after discharge. For patients with AUD who desire supplementation without risk factors for malnutrition (Table), consider prescribing a single thiamine-containing vitamin for prevention of thiamine deficiency, which, unlike other vitamin deficiencies, has the potential to be irreversible and life-threatening. Though no evidence currently supports this practice, it stands to reason that prescribing a single tablet could decrease the number of pills for patients who struggle with pill burden.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Offer evidence-based medication treatment for AUD.

- Connect patients experiencing food insecurity with appropriate resources.

- For patients initiated on a multivitamin, folate, and high-dose IV thiamine at admission, perform vitamin de-escalation during hospitalization.

- Risk-stratify hospitalized patients with AUD for additional risk factors for vitamin deficiencies (Table). In those with additional risk factors, offer supplementation if consistent with patient preference. Balance the benefits of vitamin supplementation with the risks of polypharmacy, particularly if the patient has conditions requiring multiple medications.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our case, the hospitalist initiates IV thiamine, folate, and a multivitamin at admission and assesses the patient’s nutritional status and food insecurity. The hospitalist deems the patient—who eats regular, balanced meals—to be at low risk for vitamin deficiencies. The medical team discontinues folate and multivitamins before discharge and continues IV thiamine throughout the 3-day hospitalization. The patient and clinician agree that unaddressed AUD played a key role in the patient’s heart failure exacerbation. The clinician elicits the patient’s goals around their alcohol use, discusses AUD treatment, and initiates naltrexone for AUD.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

1. Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-8-11

2. Lewis MJ. Alcoholism and nutrition: a review of vitamin supplementation and treatment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23(2):138-144. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000622

3. Bergmans RS, Coughlin L, Wilson T, Malecki K. Cross-sectional associations of food insecurity with smoking cigarettes and heavy alcohol use in a population-based sample of adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107646

4. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):911-915. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12522

5. Flannery AH, Adkins DA, Cook AM. Unpeeling the evidence for the banana bag: evidence-based recommendations for the management of alcohol-associated vitamin and electrolyte deficiencies in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1545-1552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000001659

6. Wai JM, Aloezos C, Mowrey WB, Baron SW, Cregin R, Forman HL. Using clinical decision support through the electronic medical record to increase prescribing of high-dose parenteral thiamine in hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:117-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.017

7. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. January 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/quality-science/the_asam_clinical_practice_guideline_on_alcohol-1.pdf?sfvrsn=ba255c2_2

8. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):307-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23258

9. Breu AC, Theisen-Toupal J, Feldman LS. Serum and red blood cell folate testing on hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):753-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2385

10. Gautron M-A, Questel F, Lejoyeux M, Bellivier F, Vorspan F. Nutritional status during inpatient alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(1):64-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx086

11. Li SF, Jacob J, Feng J, Kulkarni M. Vitamin deficiencies in acutely intoxicated patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(7):792-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.003

12. Ijaz S, Jackson J, Thorley H, et al. Nutritional deficiencies in homeless persons with problematic drinking: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0564-4

13. Day GS, Ladak S, Curley K, et al. Thiamine prescribing practices within university-affiliated hospitals: a multicenter retrospective review. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):246-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2324

14. Day E, Bentham PW, Callaghan R, Kuruvilla T, George S. Thiamine for prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in people who abuse alcohol. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(7):CD004033. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004033.pub3

15. Medici V, Halsted CH. Folate, alcohol, and liver disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(4):596-606. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200077

16. Ijaz S, Thorley H, Porter K, et al. Interventions for preventing or treating malnutrition in homeless problem-drinkers: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0722-3

17. Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(11):795-803. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004

18. Picker D, Heard K, Bailey TC, Martin NR, LaRossa GN, Kollef MH. The number of discharge medications predicts thirty-day hospital readmission: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0950-9

19. Han B, Jones CM, Einstein EB, Powell PA, Compton WM. Use of medications for alcohol use disorder in the US: results From the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(8):922–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1271

20. Collins SE, Duncan MH, Saxon AJ, et al. Combining behavioral harm-reduction treatment and extended-release naltrexone for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorder in the USA: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):287-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30489-2

1. Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-8-11

2. Lewis MJ. Alcoholism and nutrition: a review of vitamin supplementation and treatment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23(2):138-144. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000622

3. Bergmans RS, Coughlin L, Wilson T, Malecki K. Cross-sectional associations of food insecurity with smoking cigarettes and heavy alcohol use in a population-based sample of adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107646

4. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):911-915. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12522

5. Flannery AH, Adkins DA, Cook AM. Unpeeling the evidence for the banana bag: evidence-based recommendations for the management of alcohol-associated vitamin and electrolyte deficiencies in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1545-1552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000001659

6. Wai JM, Aloezos C, Mowrey WB, Baron SW, Cregin R, Forman HL. Using clinical decision support through the electronic medical record to increase prescribing of high-dose parenteral thiamine in hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:117-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.017

7. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. January 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/quality-science/the_asam_clinical_practice_guideline_on_alcohol-1.pdf?sfvrsn=ba255c2_2

8. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):307-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23258

9. Breu AC, Theisen-Toupal J, Feldman LS. Serum and red blood cell folate testing on hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):753-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2385

10. Gautron M-A, Questel F, Lejoyeux M, Bellivier F, Vorspan F. Nutritional status during inpatient alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(1):64-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx086

11. Li SF, Jacob J, Feng J, Kulkarni M. Vitamin deficiencies in acutely intoxicated patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(7):792-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.003

12. Ijaz S, Jackson J, Thorley H, et al. Nutritional deficiencies in homeless persons with problematic drinking: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0564-4

13. Day GS, Ladak S, Curley K, et al. Thiamine prescribing practices within university-affiliated hospitals: a multicenter retrospective review. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):246-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2324

14. Day E, Bentham PW, Callaghan R, Kuruvilla T, George S. Thiamine for prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in people who abuse alcohol. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(7):CD004033. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004033.pub3

15. Medici V, Halsted CH. Folate, alcohol, and liver disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(4):596-606. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200077

16. Ijaz S, Thorley H, Porter K, et al. Interventions for preventing or treating malnutrition in homeless problem-drinkers: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0722-3

17. Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(11):795-803. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004

18. Picker D, Heard K, Bailey TC, Martin NR, LaRossa GN, Kollef MH. The number of discharge medications predicts thirty-day hospital readmission: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0950-9

19. Han B, Jones CM, Einstein EB, Powell PA, Compton WM. Use of medications for alcohol use disorder in the US: results From the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(8):922–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1271

20. Collins SE, Duncan MH, Saxon AJ, et al. Combining behavioral harm-reduction treatment and extended-release naltrexone for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorder in the USA: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):287-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30489-2

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Things We Do for No Reason™: Discontinuing Buprenorphine When Treating Acute Pain

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR™) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR™ series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 40-year-old woman with a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) on buprenorphine-naloxone treatment is admitted to medicine following incision and drainage of a large forearm abscess with surrounding cellulitis. The patient reports severe pain following the procedure, which is not relieved by ibuprofen. The admitting hospitalist orders a pain regimen for the patient, which includes oral and intravenous hydromorphone and discontinues the patient’s buprenorphine-naloxone so that the short-acting opioids can take effect.

BACKGROUND

Medications to treat OUD include methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a Schedule III medication under the United States Food and Drug Administration that reduces opioid cravings, subsequently decreasing drug use1 and opioid-related overdose deaths.2 It has a favorable safety profile and can be prescribed for OUD in an office-based, outpatient setting since the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). Due to extensive first-pass metabolism, buprenorphine for OUD is typically administered sublingually, either alone or in a fixed combination with naloxone.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK YOU SHOULD HOLD BUPRENORPHINE WHEN TREATING ACUTE PAIN

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with a long half-life and high affinity for the mu opioid receptor. Given these properties, prior recommendations assumed that buprenorphine blocked the effectiveness of additional opioid agonists.3,4 In 2004, guidelines by the Department of Health and Human Service Center for Substance Abuse Treatment recommended discontinuing buprenorphine in patients taking opioid pain medications.5 These suggestions were based on limited case reports describing difficulty controlling pain in patients with OUD with a high opioid tolerance who were receiving buprenorphine.6

Providers may hold buprenorphine when treating acute pain out of concern it could precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opioid agonists from the mu receptor. Providers may also believe that the naloxone component in the most commonly prescribed formulation, buprenorphine-naloxone, blocks the effects of opioid analgesics. Evolving understanding of buprenorphine pharmacology and the absence of high-quality evidence has resulted in providers holding buprenorphine in the setting of acute pain.

Finally, providers without dedicated training may feel they lack the necessary qualifications to prescribe buprenorphine in the inpatient setting. DATA 2000 requires mandatory X waiver training for physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to prescribe outpatient buprenorphine for OUD treatment outside of specialized opioid treatment programs.

WHY DISCONTINUING BUPRENORPHINE WHEN TREATING ACUTE PAIN IS NOT NECESSARY

Despite buprenorphine’s high affinity at the mu receptor, additional receptors remain available for full opioid agonists to bind and activate,6 providing effective pain relief even in patients using buprenorphine. In contrast to the 2004 Department of Health and Human Service guidelines, subsequent clinical studies have demonstrated that concurrent use of opioid analgesics is effective for patients maintained on buprenorphine, similar to patients on other forms of OUD treatment such as methadone.7,8

Precipitated withdrawal only occurs when buprenorphine is newly introduced to patients with already circulating opioids. Patients receiving buprenorphine-naloxone can also be exposed to opioids without precipitated withdrawal from the naloxone component, as naloxone is not absorbed via sublingual or buccal administration, but only present in the formulation to dissuade intravenous administration of the medication.

Even in the perioperative period, there is insufficient evidence to support the discontinuation of buprenorphine.9 Studies in this patient population have found that patients receiving buprenorphine may require higher doses of short-acting opioids to achieve adequate analgesia, but they experience similar pain control, lengths of stay, and functional outcomes to controls.10 Despite variable perioperative management of buprenorphine,11 protocols at major medical centers now recommend continuing or dose adjusting buprenorphine in the perioperative period rather than discontinuing.12-14

Patients physically dependent on opioid agonists, including buprenorphine, must be maintained on a daily equivalent opioid dose to avoid experiencing withdrawal. This maintenance requirement must be met before any analgesic effect for acute pain is obtained with additional opioids. Temporarily discontinuing buprenorphine introduces unnecessary complexity to a hospitalization, places the patient at risk of exacerbation of pain, opioid withdrawal, and predisposes the patient to return to use and overdose if not resumed before hospital discharge.5

Finally, clinicians do not require additional training or an X waiver to administer buprenorphine to hospitalized patients. These requirements are limited to providers managing buprenorphine in the outpatient setting or those prescribing buprenorphine to patients to take postdischarge. Hospitalists frequently prescribe opioid medications in the inpatient setting with similar or greater safety risk profiles to buprenorphine.

WHEN YOU SHOULD CONSIDER HOLDING BUPRENORPHINE

Providers may consider holding buprenorphine if a patient with OUD has not been taking buprenorphine before hospitalization and has severe acute pain needs. This history can be confirmed with the patient and the state’s online prescription drug monitoring program. If further clarification is needed, this can be accomplished with a pharmacist and urine testing or by verifying with the patient’s opioid treatment program, as some programs provide directly administered buprenorphine.

In cases where a patient may have stopped buprenorphine before admission but wants to restart it in the hospital, it is essential to ascertain when the patient last used an opioid. The buprenorphine reinduction should be timed to a sufficient number of hours since last opioid use and/or to when the patient shows signs of active withdrawal. The re-induction can take place before, during, or after an acute pain episode, depending on the individual circumstances.

Patient preference is extremely important in the management of both pain and OUD. After shared decision-making, some patients may ultimately opt to hold buprenorphine in certain situations or switch to an alternative treatment, such as methadone, during their hospitalization. Such adjustments should be made in conjunction with the patient, primary care provider, and pain or addiction medicine specialty consultation.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

For patients on buprenorphine admitted to the hospital with anticipated or unanticipated acute pain needs, hospitalists should continue buprenorphine. Continuation of buprenorphine meets a patient’s baseline opioid requirement while still allowing the use of additional short-acting opioid agonists as needed for pain.15

As with all pain, multimodal pain management should be provided with adjunctive medications such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, neuropathic agents, topical analgesics, and regional anesthesia.8

Acute pain can be addressed by taking advantage of buprenorphine’s analgesic effects and adding additional short-acting opioids if needed.15 Several options are available, including:

1. Continuing daily buprenorphine and prescribing short-acting opioid agonists, preferably those with high intrinsic activity at the mu receptor (such as morphine, fentanyl, or hydromorphone). Full opioid agonist doses to achieve analgesia for patients on buprenorphine will be higher than in opioid naïve patients due to tolerance.16

2 .Dividing the total daily buprenorphine dose into three or four times per day dosing, since buprenorphine provides an analgesic effect lasting six to eight hours. Short-acting opioid agonists can still be prescribed on an as-needed basis for additional pain needs.

3. Temporarily increasing the total daily buprenorphine dose and dividing into three or four times per day dosing, as above. Short-acting opioid agonists can still be prescribed on an as-needed basis for additional pain needs.

It is essential to make a clear plan with the patient for initiation and discontinuation of short-acting opioid agonists or buprenorphine changes. Patients on buprenorphine should be managed collaboratively with the primary care provider or addiction specialist to coordinate prescribing and follow-up after discharge.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Continue outpatient buprenorphine treatment for patients admitted with acute pain.

- Use adjunctive nonopioid pain medications and nonpharmacologic modalities to address acute pain.

- Adjust buprenorphine to address acute pain by dividing the total daily amount into three or four times a day dosing, and/or up-titrate the buprenorphine dose (federal prescribing regulations recommend a maximum of 24 mg daily, but state regulations may vary).

- Add short-acting opioid agonists on an as-needed basis in conjunction with a defined plan to discontinue short-acting opioid agonists to avoid a return to use.

- Make plans collaboratively with the patient and outpatient provider, and communicate medication changes and plan at discharge.

CONCLUSION

Concerning our case, the hospitalist can continue the patient’s buprenorphine-naloxone, even with her acute pain needs. The patient has a baseline opioid requirement, fulfilled by continuing buprenorphine. Additional short-acting opioid agonists, such as hydromorphone, will provide analgesia for the patient, though the clinician should be aware that higher doses might be required. The practice of holding buprenorphine during episodes of acute pain is not supported by current evidence and may predispose to inadequate analgesia, opioid withdrawal, and risk of return to use and death.2

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD002207. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002207.

2. Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo M, et al. Morality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systemic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:1550. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1550.

3. Johnson RE, Fudula PJ, Payne R. Buprenorphine: considerations for pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(3):297-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.005.

4. Marcelina JS, Rubinstein A. Continuous perioperative sublingual buprenorphine. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30(4):289-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/15360288.2016.1231734.

5. Greenwald MK, Johanson CE, Moody DE, et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu-opioid receptor binding potential, plasma concentration and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(11):2000-2009. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300251.

6. Lembke A, Ottestad E, Schmiesing C. Patients maintained on buprenorphine for opioid use disorder should continue buprenorphine through the perioperative period. Pain Med. 2019;20(3):425-428. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny019.

7. Kornfeld H, Manfredi L. Effectiveness of full agonist opioids in patients stabilized on buprenorphine undergoing major surgery: A case series. Am J Ther. 2010;17(5):523-528. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181be0804.

8. Harrison TK, Kornfeld H, Aggarwal AK, Lembke A. Perioperative considerations for the patient with opioid use disorder on buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone maintenance therapy. Anesthesiol Clin. 2018;36(3):345-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2018.04.002.

9. Goel A, Azargive S, Lamba W, et al. The perioperative patient on buprenorphine: a systematic review of perioperative management strategies and patient outcomes. Can J Anesth. 2019; 66(2):201-217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-018-1255-3.

10. Hansen LE, Stone GL, Matson CA, Tybor DJ, Pevear ME, Smith EL. Total joint arthroplasty in patients taking methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone preoperatively for prior heroin addiction: a prospective matched cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(8):1698-1701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.032.

11. Jonan AB, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Buprenorphine formulations: clinical best practice strategies recommendations for perioperative management of patients undergoing surgical or interventional pain procedures. Pain Physician. 2018;21(1):E1-12. PubMed

12. Quaye AN, Zhang Y. Perioperative management of buprenorphine: solving the conundrum. Pain Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny217.

13. Silva MJ, Rubinstein A. Continuous perioperative sublingual buprenorphine. J Pain Palliative Care Pharmacother. 2016;30(4):289-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/15360288.2016.1231734.

14. Kampman K, Jarvis M. ASAM National practice guidelines for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358-367. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166.

15. Childers JW, Arnold RM. Treatment of pain in patients taking buprenorphine for opioid addiction. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):613-614. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.9591.

16. Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):127-134. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00010

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR™) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR™ series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 40-year-old woman with a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) on buprenorphine-naloxone treatment is admitted to medicine following incision and drainage of a large forearm abscess with surrounding cellulitis. The patient reports severe pain following the procedure, which is not relieved by ibuprofen. The admitting hospitalist orders a pain regimen for the patient, which includes oral and intravenous hydromorphone and discontinues the patient’s buprenorphine-naloxone so that the short-acting opioids can take effect.

BACKGROUND

Medications to treat OUD include methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a Schedule III medication under the United States Food and Drug Administration that reduces opioid cravings, subsequently decreasing drug use1 and opioid-related overdose deaths.2 It has a favorable safety profile and can be prescribed for OUD in an office-based, outpatient setting since the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). Due to extensive first-pass metabolism, buprenorphine for OUD is typically administered sublingually, either alone or in a fixed combination with naloxone.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK YOU SHOULD HOLD BUPRENORPHINE WHEN TREATING ACUTE PAIN

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with a long half-life and high affinity for the mu opioid receptor. Given these properties, prior recommendations assumed that buprenorphine blocked the effectiveness of additional opioid agonists.3,4 In 2004, guidelines by the Department of Health and Human Service Center for Substance Abuse Treatment recommended discontinuing buprenorphine in patients taking opioid pain medications.5 These suggestions were based on limited case reports describing difficulty controlling pain in patients with OUD with a high opioid tolerance who were receiving buprenorphine.6

Providers may hold buprenorphine when treating acute pain out of concern it could precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opioid agonists from the mu receptor. Providers may also believe that the naloxone component in the most commonly prescribed formulation, buprenorphine-naloxone, blocks the effects of opioid analgesics. Evolving understanding of buprenorphine pharmacology and the absence of high-quality evidence has resulted in providers holding buprenorphine in the setting of acute pain.

Finally, providers without dedicated training may feel they lack the necessary qualifications to prescribe buprenorphine in the inpatient setting. DATA 2000 requires mandatory X waiver training for physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to prescribe outpatient buprenorphine for OUD treatment outside of specialized opioid treatment programs.

WHY DISCONTINUING BUPRENORPHINE WHEN TREATING ACUTE PAIN IS NOT NECESSARY

Despite buprenorphine’s high affinity at the mu receptor, additional receptors remain available for full opioid agonists to bind and activate,6 providing effective pain relief even in patients using buprenorphine. In contrast to the 2004 Department of Health and Human Service guidelines, subsequent clinical studies have demonstrated that concurrent use of opioid analgesics is effective for patients maintained on buprenorphine, similar to patients on other forms of OUD treatment such as methadone.7,8

Precipitated withdrawal only occurs when buprenorphine is newly introduced to patients with already circulating opioids. Patients receiving buprenorphine-naloxone can also be exposed to opioids without precipitated withdrawal from the naloxone component, as naloxone is not absorbed via sublingual or buccal administration, but only present in the formulation to dissuade intravenous administration of the medication.

Even in the perioperative period, there is insufficient evidence to support the discontinuation of buprenorphine.9 Studies in this patient population have found that patients receiving buprenorphine may require higher doses of short-acting opioids to achieve adequate analgesia, but they experience similar pain control, lengths of stay, and functional outcomes to controls.10 Despite variable perioperative management of buprenorphine,11 protocols at major medical centers now recommend continuing or dose adjusting buprenorphine in the perioperative period rather than discontinuing.12-14

Patients physically dependent on opioid agonists, including buprenorphine, must be maintained on a daily equivalent opioid dose to avoid experiencing withdrawal. This maintenance requirement must be met before any analgesic effect for acute pain is obtained with additional opioids. Temporarily discontinuing buprenorphine introduces unnecessary complexity to a hospitalization, places the patient at risk of exacerbation of pain, opioid withdrawal, and predisposes the patient to return to use and overdose if not resumed before hospital discharge.5

Finally, clinicians do not require additional training or an X waiver to administer buprenorphine to hospitalized patients. These requirements are limited to providers managing buprenorphine in the outpatient setting or those prescribing buprenorphine to patients to take postdischarge. Hospitalists frequently prescribe opioid medications in the inpatient setting with similar or greater safety risk profiles to buprenorphine.

WHEN YOU SHOULD CONSIDER HOLDING BUPRENORPHINE

Providers may consider holding buprenorphine if a patient with OUD has not been taking buprenorphine before hospitalization and has severe acute pain needs. This history can be confirmed with the patient and the state’s online prescription drug monitoring program. If further clarification is needed, this can be accomplished with a pharmacist and urine testing or by verifying with the patient’s opioid treatment program, as some programs provide directly administered buprenorphine.

In cases where a patient may have stopped buprenorphine before admission but wants to restart it in the hospital, it is essential to ascertain when the patient last used an opioid. The buprenorphine reinduction should be timed to a sufficient number of hours since last opioid use and/or to when the patient shows signs of active withdrawal. The re-induction can take place before, during, or after an acute pain episode, depending on the individual circumstances.

Patient preference is extremely important in the management of both pain and OUD. After shared decision-making, some patients may ultimately opt to hold buprenorphine in certain situations or switch to an alternative treatment, such as methadone, during their hospitalization. Such adjustments should be made in conjunction with the patient, primary care provider, and pain or addiction medicine specialty consultation.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

For patients on buprenorphine admitted to the hospital with anticipated or unanticipated acute pain needs, hospitalists should continue buprenorphine. Continuation of buprenorphine meets a patient’s baseline opioid requirement while still allowing the use of additional short-acting opioid agonists as needed for pain.15

As with all pain, multimodal pain management should be provided with adjunctive medications such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, neuropathic agents, topical analgesics, and regional anesthesia.8

Acute pain can be addressed by taking advantage of buprenorphine’s analgesic effects and adding additional short-acting opioids if needed.15 Several options are available, including:

1. Continuing daily buprenorphine and prescribing short-acting opioid agonists, preferably those with high intrinsic activity at the mu receptor (such as morphine, fentanyl, or hydromorphone). Full opioid agonist doses to achieve analgesia for patients on buprenorphine will be higher than in opioid naïve patients due to tolerance.16

2 .Dividing the total daily buprenorphine dose into three or four times per day dosing, since buprenorphine provides an analgesic effect lasting six to eight hours. Short-acting opioid agonists can still be prescribed on an as-needed basis for additional pain needs.

3. Temporarily increasing the total daily buprenorphine dose and dividing into three or four times per day dosing, as above. Short-acting opioid agonists can still be prescribed on an as-needed basis for additional pain needs.

It is essential to make a clear plan with the patient for initiation and discontinuation of short-acting opioid agonists or buprenorphine changes. Patients on buprenorphine should be managed collaboratively with the primary care provider or addiction specialist to coordinate prescribing and follow-up after discharge.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Continue outpatient buprenorphine treatment for patients admitted with acute pain.

- Use adjunctive nonopioid pain medications and nonpharmacologic modalities to address acute pain.

- Adjust buprenorphine to address acute pain by dividing the total daily amount into three or four times a day dosing, and/or up-titrate the buprenorphine dose (federal prescribing regulations recommend a maximum of 24 mg daily, but state regulations may vary).

- Add short-acting opioid agonists on an as-needed basis in conjunction with a defined plan to discontinue short-acting opioid agonists to avoid a return to use.

- Make plans collaboratively with the patient and outpatient provider, and communicate medication changes and plan at discharge.

CONCLUSION

Concerning our case, the hospitalist can continue the patient’s buprenorphine-naloxone, even with her acute pain needs. The patient has a baseline opioid requirement, fulfilled by continuing buprenorphine. Additional short-acting opioid agonists, such as hydromorphone, will provide analgesia for the patient, though the clinician should be aware that higher doses might be required. The practice of holding buprenorphine during episodes of acute pain is not supported by current evidence and may predispose to inadequate analgesia, opioid withdrawal, and risk of return to use and death.2

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR™) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR™ series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 40-year-old woman with a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) on buprenorphine-naloxone treatment is admitted to medicine following incision and drainage of a large forearm abscess with surrounding cellulitis. The patient reports severe pain following the procedure, which is not relieved by ibuprofen. The admitting hospitalist orders a pain regimen for the patient, which includes oral and intravenous hydromorphone and discontinues the patient’s buprenorphine-naloxone so that the short-acting opioids can take effect.

BACKGROUND

Medications to treat OUD include methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a Schedule III medication under the United States Food and Drug Administration that reduces opioid cravings, subsequently decreasing drug use1 and opioid-related overdose deaths.2 It has a favorable safety profile and can be prescribed for OUD in an office-based, outpatient setting since the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). Due to extensive first-pass metabolism, buprenorphine for OUD is typically administered sublingually, either alone or in a fixed combination with naloxone.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK YOU SHOULD HOLD BUPRENORPHINE WHEN TREATING ACUTE PAIN

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with a long half-life and high affinity for the mu opioid receptor. Given these properties, prior recommendations assumed that buprenorphine blocked the effectiveness of additional opioid agonists.3,4 In 2004, guidelines by the Department of Health and Human Service Center for Substance Abuse Treatment recommended discontinuing buprenorphine in patients taking opioid pain medications.5 These suggestions were based on limited case reports describing difficulty controlling pain in patients with OUD with a high opioid tolerance who were receiving buprenorphine.6

Providers may hold buprenorphine when treating acute pain out of concern it could precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opioid agonists from the mu receptor. Providers may also believe that the naloxone component in the most commonly prescribed formulation, buprenorphine-naloxone, blocks the effects of opioid analgesics. Evolving understanding of buprenorphine pharmacology and the absence of high-quality evidence has resulted in providers holding buprenorphine in the setting of acute pain.

Finally, providers without dedicated training may feel they lack the necessary qualifications to prescribe buprenorphine in the inpatient setting. DATA 2000 requires mandatory X waiver training for physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to prescribe outpatient buprenorphine for OUD treatment outside of specialized opioid treatment programs.

WHY DISCONTINUING BUPRENORPHINE WHEN TREATING ACUTE PAIN IS NOT NECESSARY

Despite buprenorphine’s high affinity at the mu receptor, additional receptors remain available for full opioid agonists to bind and activate,6 providing effective pain relief even in patients using buprenorphine. In contrast to the 2004 Department of Health and Human Service guidelines, subsequent clinical studies have demonstrated that concurrent use of opioid analgesics is effective for patients maintained on buprenorphine, similar to patients on other forms of OUD treatment such as methadone.7,8

Precipitated withdrawal only occurs when buprenorphine is newly introduced to patients with already circulating opioids. Patients receiving buprenorphine-naloxone can also be exposed to opioids without precipitated withdrawal from the naloxone component, as naloxone is not absorbed via sublingual or buccal administration, but only present in the formulation to dissuade intravenous administration of the medication.

Even in the perioperative period, there is insufficient evidence to support the discontinuation of buprenorphine.9 Studies in this patient population have found that patients receiving buprenorphine may require higher doses of short-acting opioids to achieve adequate analgesia, but they experience similar pain control, lengths of stay, and functional outcomes to controls.10 Despite variable perioperative management of buprenorphine,11 protocols at major medical centers now recommend continuing or dose adjusting buprenorphine in the perioperative period rather than discontinuing.12-14

Patients physically dependent on opioid agonists, including buprenorphine, must be maintained on a daily equivalent opioid dose to avoid experiencing withdrawal. This maintenance requirement must be met before any analgesic effect for acute pain is obtained with additional opioids. Temporarily discontinuing buprenorphine introduces unnecessary complexity to a hospitalization, places the patient at risk of exacerbation of pain, opioid withdrawal, and predisposes the patient to return to use and overdose if not resumed before hospital discharge.5

Finally, clinicians do not require additional training or an X waiver to administer buprenorphine to hospitalized patients. These requirements are limited to providers managing buprenorphine in the outpatient setting or those prescribing buprenorphine to patients to take postdischarge. Hospitalists frequently prescribe opioid medications in the inpatient setting with similar or greater safety risk profiles to buprenorphine.

WHEN YOU SHOULD CONSIDER HOLDING BUPRENORPHINE