User login

“...but it all started to get worse during the pandemic.”

As the patient’s† door closed, I (JS) thought about what his father had shared: his 12-year-old son had experienced a slow decline in his mental health since March 2020. There had been a gradual loss of all the things his son needed for psychological well-being: school went virtual and extracurricular activities ceased, and with them went any sense of routine, normalcy, or authentic opportunities to socialize. His feelings of isolation and depression culminated in an attempt to end his own life. My mind shifted to other patients under our care: an 8-year-old with behavioral outbursts intensifying after school-based therapy ended, a 13-year-old who became suicidal from isolation and virtual bullying. These children’s families sought emergent care because they no longer had the resources to care for their children at home. My team left each of these rooms heartbroken, unsure of exactly what to say and aware of the limitations of our current healthcare system.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many pediatric providers have had similar experiences caring for countless patients who are “boarding”—awaiting transfer to a psychiatric facility for their primary acute psychiatric issue, initially in the emergency room, often for 5 days or more,1 then ultimately admitted to a general medical floor if an appropriate psychiatric bed is still not available.2 Unfortunately, just as parents have run out of resources to care for their children’s psychiatric needs, so too is our medical system lacking in resources to provide the acute care these children need in general hospitals.

This mental health crisis began before the COVID-19 pandemic3 but has only worsened in the wake of its resulting social isolation. During the pandemic, suicide hotlines had a 1000% increase in call volumes.4 COVID-19–induced bed closures simultaneously worsened an existing critical bed shortage5,6 and led to an increase in the average length of stay (LOS) for patients boarding in the emergency department (ED).7 In the state of Massachusetts, for example, psychiatric patients awaiting inpatient beds boarded for more than 10,000 hours in January 2021—more than ever before, and up approximately 4000 hours since January 2017.6 For pediatric patients, the average wait time is now 59 hours.6 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, 39% of children presenting to EDs for mental health complaints ended up boarding, which is an astounding figure and is unfortunately 7% higher than in 2019.8 Even these staggering numbers do not capture the full range of experiences, as many statistics do not account for time spent on inpatient units by patients who do not receive a bed placement after waiting hours to several days in the ED.

Shortages of space, as well as an underfunded and understaffed mental health workforce, lead to these prolonged, often traumatic boarding periods in hospitals designed to care for acute medical, rather than acute psychiatric, conditions. Patients awaiting psychiatric placement are waiting in settings that are chaotic, inconsistent, and lacking in privacy. A patient in the throes of psychosis or suicidality needs a therapeutic milieu, not one that interrupts their daily routine,2 disconnects them from their existing support networks, and is punctuated by the incessant clangs of bedside monitors and the hubbub of code teams. These environments are not therapeutic3 for young infants with fevers, let alone for teenagers battling suicidality and eating disorders. In fact, for these reasons, we suspect that many of our patients’ inpatient ”behavioral escalations” are in fact triggered by their hospital environment, which may contribute to the 300% increase in the number of pharmacological restraints used during mental health visits in the ED over the past 10 years.9

None of us imagined when we chose to pursue pediatrics a that significant—and at times predominant—portion of our training would encompass caring for patients with acute mental health concerns. And although we did not anticipate this crisis, we have now been tasked with managing it. Throughout the day, when we are called to see our patients with primarily psychiatric pathology, we are often at war with ourselves. We weigh forming deeply meaningful relationships with these patients against the potential of unintentionally retraumatizing them or forming bonds that will be abruptly severed when patients are transferred to a psychiatric facility, which often occurs with barely a few hours’ notice. Moreover, many healthcare workers have training ill-suited to meet the needs of these patients. Just as emergency physicians can diagnose appendicitis but rely on surgeons to provide timely surgical treatment, general pediatricians identify psychiatric crises but rely on psychiatrists for ideal treatment plans. And almost daily, we are called to an “escalating” patient and arrive minutes into a stressful situation that others expect us to extinguish expeditiously. Along with nursing colleagues and the behavioral response team, we enact the treatment plan laid out by our psychiatry colleagues and wonder whether there is a better way.

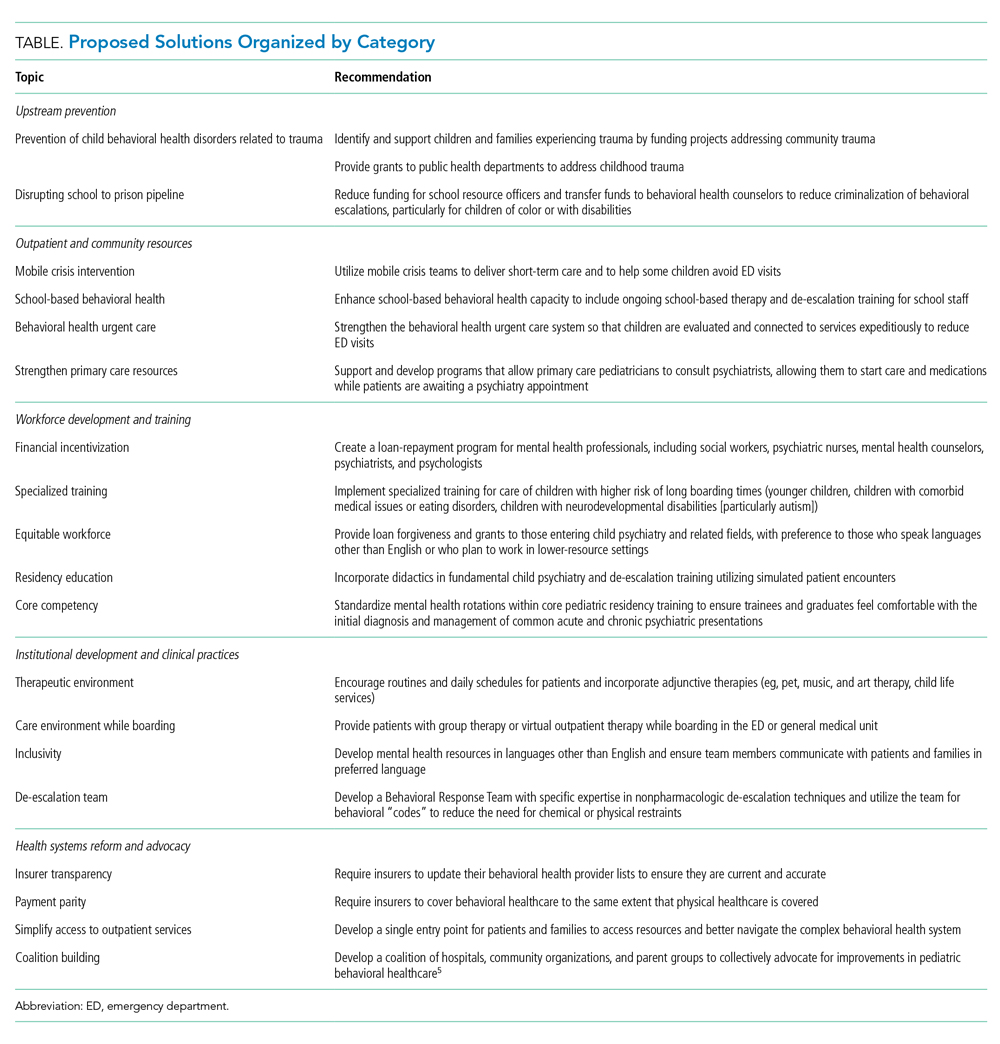

We propose the following changes to create a more ideal health system (Table). We acknowledge that each health system has unique resources, challenges, and patient populations. Thus, our recommendations are not comprehensive and are largely based on experiences within our own institutions and state, but they encompass many domains that impact and are affected by child and adolescent mental healthcare in the United States, ranging from program- and hospital-level innovation to community and legislative action.

UPSTREAM PREVENTION

Like all good health system designs, we recommend prioritizing prevention. This would entail funding programs and legislation such as H.R. 3180, the RISE from Trauma Act, and H.R. 8544, the STRONG Support for Children Act of 2020 (both currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives) that support early childhood development and prevent adverse childhood experiences and trauma, averting mental health diagnoses such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder before they begin.10

OUTPATIENT AND COMMUNITY RESOURCES

We recognize that schools and general pediatricians have far more exposure to children at risk for mental health crises than do subspecialists. Thus, we urge an equitable increase in access to mental healthcare in the community so that patients needing assistance are screened and diagnosed earlier in their illness, allowing for secondary prevention of worsening mental health disorders. We support increased funding for programs such as the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, which allows primary care doctors to consult psychiatrists in real time, closing the gap between a primary care visit and specialty follow-up. Telehealth services will be key to improving access for patients themselves and to allow pediatricians to consult with mental health professionals to initiate care prior to specialist availability. We envision that strengthening school-based behavioral health resources will also help prevent ED visits. Behavioral healthcare should be integrated into schools and community centers while police presence is simultaneously reduced, as there is evidence of an increased likelihood of juvenile justice involvement for children with disabilities and mental health needs.11,12

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT AND TRAINING

Ensuring access necessitates increasing the capacity of our psychiatric workforce by encouraging graduates to pursue mental health occupations with concrete financial incentives such as loan repayment and training grants. We thus support legislation such as H.R. 6597, the Mental Health Professionals Workforce Shortage Loan Repayment Act of 2018 (currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives). This may also improve recruitment and retention of individuals who are underrepresented in medicine, one step in helping ensure children have access to linguistically appropriate and culturally sensitive care. Residency programs and hospital systems should expand their training and education to identify and stabilize patients in mental health in extremis through culturally sensitive curricula focused on behavioral de-escalation techniques, trauma-informed care, and psychopharmacology. Our own residency program created a 2-week mental health rotation13 that includes rotating with outpatient mental health providers and our hospital’s behavioral response team, a group of trauma-informed responders for behavioral emergencies. Similar training should be available for nursing and other allied health professionals, who are often the first responders to behavioral escalations.13

INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND CLINICAL PRACTICES

Ideally, patients requiring higher-intensity psychiatric care would be referred to specialized pediatric behavioral health urgent care centers so their conditions can be adequately evaluated and addressed by staff trained in psychiatric management and in therapeutic environments. We believe all providers caring for children with mental health needs should be trained in basic, but core, behavioral health and de-escalation competencies, including specialized training for children with comorbid medical and neurodevelopmental diagnoses, such as autism. These centers should have specific beds for young children and those with developmental or complex care needs, and services should be available in numerous languages and levels of health literacy to allow all families to participate in their child’s care. At the same time, even nonpsychiatric EDs and inpatient units should commit resources to developing a maximally therapeutic environment, including allowing adjunctive services such as child life services, group therapy, and pet and music therapy, and create environments that support, rather than disrupt, normal routines.

HEALTH SYSTEMS REFORM AND ADVOCACY

Underpinning all the above innovations are changes to our healthcare payment system and provider networks, including the need for insurance coverage and payment parity for behavioral health, to ensure care is not only accessible but affordable. Additionally, for durable change, we need more than just education—we need coalition building and advocacy. Many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have begun this work, which we must all continue.14 Bringing in diverse partners, including health systems, providers, educators, hospital administrators, payors, elected officials, and communities, will prioritize children’s needs and create a more ideal pediatric behavioral healthcare system.15

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire need for comprehensive mental healthcare in the United States, a need that existed before the pandemic and will persist in a more fragile state long after it ends. Our hope is that the pandemic serves as the catalyst necessary to promote the magnitude of investments and stakeholder buy-in necessary to improve pediatric mental health and engender a radical redesign of our behavioral healthcare system. Our patients are counting on us to act. Together, we can build a system that ensures that the kids will be alright.

†Patient details have been changed for patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Perdomo, MD, Amara Azubuike, JD, and Josh Greenberg, JD, for reading and providing feedback on earlier versions of this work.

1. “This is a crisis”: mom whose son has boarded 33 days for psych bed calls for state action. WBUR News. Updated March 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/26/mental-health-boarding-hospitals

2. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813-824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

3. Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005-2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-030692

4. Cloutier RL, Marshaall R. A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:776-777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008

5. Schoenberg S. Lack of mental health beds means long ER waits. CommonWealth Magazine. April 15, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://commonwealthmagazine.org/health-care/lack-of-mental-health-beds-means-long-er-waits/

6. Jolicoeur L, Mullins L. Mass. physicians call on state to address ER “boarding” of patients awaiting admission. WBUR News. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/02/emergency-department-er-inpatient-beds-boarding

7. Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533

8. Impact of COVID-19 on the Massachusetts Health Care System: Interim Report. Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. April 2021. Accessed September 25, 2021. www.mass.gov/doc/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-massachusetts-health-care-system-interim-report/download

9. Foster AA, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Hoffmann JA, Hudgins JD. Pharmacologic restraint use during mental health visits in pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2021;236:276-283.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.027

10. Brown NM, Brown SN, Briggs RD, Germán M, Belamarich PF, Oyeku SO. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):349-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013

11. Harper K, Ryberg R, Temkin D. Black students and students with disabilities remain more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions, despite overall declines. Child Trends. April 29, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.childtrends.org/publications/black-students-disabilities-out-of-school-suspensions

12. Whitaker A, Torres-Guillén S, Morton M, et al. Cops and no counselors: how the lack of school mental health staff is harming students. American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed August 6, 2021. www.aclu.org/report/cops-and-no-counselors

13. Education. Boston Combined Residence Program. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://msbcrp.wpengine.com/program/education/

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Interim guidance on supporting the emotional and behavioral health needs of children, adolescents, and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated July 28, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. http://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/interim-guidance-on-supporting-the-emotional-and-behavioral-health-needs-of-children-adolescents-and-families-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

15. Advocacy. Children’s Mental Health Campaign. Accessed August 4, 2021. https://childrensmentalhealthcampaign.org/advocacy

“...but it all started to get worse during the pandemic.”

As the patient’s† door closed, I (JS) thought about what his father had shared: his 12-year-old son had experienced a slow decline in his mental health since March 2020. There had been a gradual loss of all the things his son needed for psychological well-being: school went virtual and extracurricular activities ceased, and with them went any sense of routine, normalcy, or authentic opportunities to socialize. His feelings of isolation and depression culminated in an attempt to end his own life. My mind shifted to other patients under our care: an 8-year-old with behavioral outbursts intensifying after school-based therapy ended, a 13-year-old who became suicidal from isolation and virtual bullying. These children’s families sought emergent care because they no longer had the resources to care for their children at home. My team left each of these rooms heartbroken, unsure of exactly what to say and aware of the limitations of our current healthcare system.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many pediatric providers have had similar experiences caring for countless patients who are “boarding”—awaiting transfer to a psychiatric facility for their primary acute psychiatric issue, initially in the emergency room, often for 5 days or more,1 then ultimately admitted to a general medical floor if an appropriate psychiatric bed is still not available.2 Unfortunately, just as parents have run out of resources to care for their children’s psychiatric needs, so too is our medical system lacking in resources to provide the acute care these children need in general hospitals.

This mental health crisis began before the COVID-19 pandemic3 but has only worsened in the wake of its resulting social isolation. During the pandemic, suicide hotlines had a 1000% increase in call volumes.4 COVID-19–induced bed closures simultaneously worsened an existing critical bed shortage5,6 and led to an increase in the average length of stay (LOS) for patients boarding in the emergency department (ED).7 In the state of Massachusetts, for example, psychiatric patients awaiting inpatient beds boarded for more than 10,000 hours in January 2021—more than ever before, and up approximately 4000 hours since January 2017.6 For pediatric patients, the average wait time is now 59 hours.6 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, 39% of children presenting to EDs for mental health complaints ended up boarding, which is an astounding figure and is unfortunately 7% higher than in 2019.8 Even these staggering numbers do not capture the full range of experiences, as many statistics do not account for time spent on inpatient units by patients who do not receive a bed placement after waiting hours to several days in the ED.

Shortages of space, as well as an underfunded and understaffed mental health workforce, lead to these prolonged, often traumatic boarding periods in hospitals designed to care for acute medical, rather than acute psychiatric, conditions. Patients awaiting psychiatric placement are waiting in settings that are chaotic, inconsistent, and lacking in privacy. A patient in the throes of psychosis or suicidality needs a therapeutic milieu, not one that interrupts their daily routine,2 disconnects them from their existing support networks, and is punctuated by the incessant clangs of bedside monitors and the hubbub of code teams. These environments are not therapeutic3 for young infants with fevers, let alone for teenagers battling suicidality and eating disorders. In fact, for these reasons, we suspect that many of our patients’ inpatient ”behavioral escalations” are in fact triggered by their hospital environment, which may contribute to the 300% increase in the number of pharmacological restraints used during mental health visits in the ED over the past 10 years.9

None of us imagined when we chose to pursue pediatrics a that significant—and at times predominant—portion of our training would encompass caring for patients with acute mental health concerns. And although we did not anticipate this crisis, we have now been tasked with managing it. Throughout the day, when we are called to see our patients with primarily psychiatric pathology, we are often at war with ourselves. We weigh forming deeply meaningful relationships with these patients against the potential of unintentionally retraumatizing them or forming bonds that will be abruptly severed when patients are transferred to a psychiatric facility, which often occurs with barely a few hours’ notice. Moreover, many healthcare workers have training ill-suited to meet the needs of these patients. Just as emergency physicians can diagnose appendicitis but rely on surgeons to provide timely surgical treatment, general pediatricians identify psychiatric crises but rely on psychiatrists for ideal treatment plans. And almost daily, we are called to an “escalating” patient and arrive minutes into a stressful situation that others expect us to extinguish expeditiously. Along with nursing colleagues and the behavioral response team, we enact the treatment plan laid out by our psychiatry colleagues and wonder whether there is a better way.

We propose the following changes to create a more ideal health system (Table). We acknowledge that each health system has unique resources, challenges, and patient populations. Thus, our recommendations are not comprehensive and are largely based on experiences within our own institutions and state, but they encompass many domains that impact and are affected by child and adolescent mental healthcare in the United States, ranging from program- and hospital-level innovation to community and legislative action.

UPSTREAM PREVENTION

Like all good health system designs, we recommend prioritizing prevention. This would entail funding programs and legislation such as H.R. 3180, the RISE from Trauma Act, and H.R. 8544, the STRONG Support for Children Act of 2020 (both currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives) that support early childhood development and prevent adverse childhood experiences and trauma, averting mental health diagnoses such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder before they begin.10

OUTPATIENT AND COMMUNITY RESOURCES

We recognize that schools and general pediatricians have far more exposure to children at risk for mental health crises than do subspecialists. Thus, we urge an equitable increase in access to mental healthcare in the community so that patients needing assistance are screened and diagnosed earlier in their illness, allowing for secondary prevention of worsening mental health disorders. We support increased funding for programs such as the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, which allows primary care doctors to consult psychiatrists in real time, closing the gap between a primary care visit and specialty follow-up. Telehealth services will be key to improving access for patients themselves and to allow pediatricians to consult with mental health professionals to initiate care prior to specialist availability. We envision that strengthening school-based behavioral health resources will also help prevent ED visits. Behavioral healthcare should be integrated into schools and community centers while police presence is simultaneously reduced, as there is evidence of an increased likelihood of juvenile justice involvement for children with disabilities and mental health needs.11,12

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT AND TRAINING

Ensuring access necessitates increasing the capacity of our psychiatric workforce by encouraging graduates to pursue mental health occupations with concrete financial incentives such as loan repayment and training grants. We thus support legislation such as H.R. 6597, the Mental Health Professionals Workforce Shortage Loan Repayment Act of 2018 (currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives). This may also improve recruitment and retention of individuals who are underrepresented in medicine, one step in helping ensure children have access to linguistically appropriate and culturally sensitive care. Residency programs and hospital systems should expand their training and education to identify and stabilize patients in mental health in extremis through culturally sensitive curricula focused on behavioral de-escalation techniques, trauma-informed care, and psychopharmacology. Our own residency program created a 2-week mental health rotation13 that includes rotating with outpatient mental health providers and our hospital’s behavioral response team, a group of trauma-informed responders for behavioral emergencies. Similar training should be available for nursing and other allied health professionals, who are often the first responders to behavioral escalations.13

INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND CLINICAL PRACTICES

Ideally, patients requiring higher-intensity psychiatric care would be referred to specialized pediatric behavioral health urgent care centers so their conditions can be adequately evaluated and addressed by staff trained in psychiatric management and in therapeutic environments. We believe all providers caring for children with mental health needs should be trained in basic, but core, behavioral health and de-escalation competencies, including specialized training for children with comorbid medical and neurodevelopmental diagnoses, such as autism. These centers should have specific beds for young children and those with developmental or complex care needs, and services should be available in numerous languages and levels of health literacy to allow all families to participate in their child’s care. At the same time, even nonpsychiatric EDs and inpatient units should commit resources to developing a maximally therapeutic environment, including allowing adjunctive services such as child life services, group therapy, and pet and music therapy, and create environments that support, rather than disrupt, normal routines.

HEALTH SYSTEMS REFORM AND ADVOCACY

Underpinning all the above innovations are changes to our healthcare payment system and provider networks, including the need for insurance coverage and payment parity for behavioral health, to ensure care is not only accessible but affordable. Additionally, for durable change, we need more than just education—we need coalition building and advocacy. Many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have begun this work, which we must all continue.14 Bringing in diverse partners, including health systems, providers, educators, hospital administrators, payors, elected officials, and communities, will prioritize children’s needs and create a more ideal pediatric behavioral healthcare system.15

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire need for comprehensive mental healthcare in the United States, a need that existed before the pandemic and will persist in a more fragile state long after it ends. Our hope is that the pandemic serves as the catalyst necessary to promote the magnitude of investments and stakeholder buy-in necessary to improve pediatric mental health and engender a radical redesign of our behavioral healthcare system. Our patients are counting on us to act. Together, we can build a system that ensures that the kids will be alright.

†Patient details have been changed for patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Perdomo, MD, Amara Azubuike, JD, and Josh Greenberg, JD, for reading and providing feedback on earlier versions of this work.

“...but it all started to get worse during the pandemic.”

As the patient’s† door closed, I (JS) thought about what his father had shared: his 12-year-old son had experienced a slow decline in his mental health since March 2020. There had been a gradual loss of all the things his son needed for psychological well-being: school went virtual and extracurricular activities ceased, and with them went any sense of routine, normalcy, or authentic opportunities to socialize. His feelings of isolation and depression culminated in an attempt to end his own life. My mind shifted to other patients under our care: an 8-year-old with behavioral outbursts intensifying after school-based therapy ended, a 13-year-old who became suicidal from isolation and virtual bullying. These children’s families sought emergent care because they no longer had the resources to care for their children at home. My team left each of these rooms heartbroken, unsure of exactly what to say and aware of the limitations of our current healthcare system.

Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many pediatric providers have had similar experiences caring for countless patients who are “boarding”—awaiting transfer to a psychiatric facility for their primary acute psychiatric issue, initially in the emergency room, often for 5 days or more,1 then ultimately admitted to a general medical floor if an appropriate psychiatric bed is still not available.2 Unfortunately, just as parents have run out of resources to care for their children’s psychiatric needs, so too is our medical system lacking in resources to provide the acute care these children need in general hospitals.

This mental health crisis began before the COVID-19 pandemic3 but has only worsened in the wake of its resulting social isolation. During the pandemic, suicide hotlines had a 1000% increase in call volumes.4 COVID-19–induced bed closures simultaneously worsened an existing critical bed shortage5,6 and led to an increase in the average length of stay (LOS) for patients boarding in the emergency department (ED).7 In the state of Massachusetts, for example, psychiatric patients awaiting inpatient beds boarded for more than 10,000 hours in January 2021—more than ever before, and up approximately 4000 hours since January 2017.6 For pediatric patients, the average wait time is now 59 hours.6 In the first 6 months of the pandemic, 39% of children presenting to EDs for mental health complaints ended up boarding, which is an astounding figure and is unfortunately 7% higher than in 2019.8 Even these staggering numbers do not capture the full range of experiences, as many statistics do not account for time spent on inpatient units by patients who do not receive a bed placement after waiting hours to several days in the ED.

Shortages of space, as well as an underfunded and understaffed mental health workforce, lead to these prolonged, often traumatic boarding periods in hospitals designed to care for acute medical, rather than acute psychiatric, conditions. Patients awaiting psychiatric placement are waiting in settings that are chaotic, inconsistent, and lacking in privacy. A patient in the throes of psychosis or suicidality needs a therapeutic milieu, not one that interrupts their daily routine,2 disconnects them from their existing support networks, and is punctuated by the incessant clangs of bedside monitors and the hubbub of code teams. These environments are not therapeutic3 for young infants with fevers, let alone for teenagers battling suicidality and eating disorders. In fact, for these reasons, we suspect that many of our patients’ inpatient ”behavioral escalations” are in fact triggered by their hospital environment, which may contribute to the 300% increase in the number of pharmacological restraints used during mental health visits in the ED over the past 10 years.9

None of us imagined when we chose to pursue pediatrics a that significant—and at times predominant—portion of our training would encompass caring for patients with acute mental health concerns. And although we did not anticipate this crisis, we have now been tasked with managing it. Throughout the day, when we are called to see our patients with primarily psychiatric pathology, we are often at war with ourselves. We weigh forming deeply meaningful relationships with these patients against the potential of unintentionally retraumatizing them or forming bonds that will be abruptly severed when patients are transferred to a psychiatric facility, which often occurs with barely a few hours’ notice. Moreover, many healthcare workers have training ill-suited to meet the needs of these patients. Just as emergency physicians can diagnose appendicitis but rely on surgeons to provide timely surgical treatment, general pediatricians identify psychiatric crises but rely on psychiatrists for ideal treatment plans. And almost daily, we are called to an “escalating” patient and arrive minutes into a stressful situation that others expect us to extinguish expeditiously. Along with nursing colleagues and the behavioral response team, we enact the treatment plan laid out by our psychiatry colleagues and wonder whether there is a better way.

We propose the following changes to create a more ideal health system (Table). We acknowledge that each health system has unique resources, challenges, and patient populations. Thus, our recommendations are not comprehensive and are largely based on experiences within our own institutions and state, but they encompass many domains that impact and are affected by child and adolescent mental healthcare in the United States, ranging from program- and hospital-level innovation to community and legislative action.

UPSTREAM PREVENTION

Like all good health system designs, we recommend prioritizing prevention. This would entail funding programs and legislation such as H.R. 3180, the RISE from Trauma Act, and H.R. 8544, the STRONG Support for Children Act of 2020 (both currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives) that support early childhood development and prevent adverse childhood experiences and trauma, averting mental health diagnoses such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder before they begin.10

OUTPATIENT AND COMMUNITY RESOURCES

We recognize that schools and general pediatricians have far more exposure to children at risk for mental health crises than do subspecialists. Thus, we urge an equitable increase in access to mental healthcare in the community so that patients needing assistance are screened and diagnosed earlier in their illness, allowing for secondary prevention of worsening mental health disorders. We support increased funding for programs such as the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, which allows primary care doctors to consult psychiatrists in real time, closing the gap between a primary care visit and specialty follow-up. Telehealth services will be key to improving access for patients themselves and to allow pediatricians to consult with mental health professionals to initiate care prior to specialist availability. We envision that strengthening school-based behavioral health resources will also help prevent ED visits. Behavioral healthcare should be integrated into schools and community centers while police presence is simultaneously reduced, as there is evidence of an increased likelihood of juvenile justice involvement for children with disabilities and mental health needs.11,12

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT AND TRAINING

Ensuring access necessitates increasing the capacity of our psychiatric workforce by encouraging graduates to pursue mental health occupations with concrete financial incentives such as loan repayment and training grants. We thus support legislation such as H.R. 6597, the Mental Health Professionals Workforce Shortage Loan Repayment Act of 2018 (currently under consideration in the US House of Representatives). This may also improve recruitment and retention of individuals who are underrepresented in medicine, one step in helping ensure children have access to linguistically appropriate and culturally sensitive care. Residency programs and hospital systems should expand their training and education to identify and stabilize patients in mental health in extremis through culturally sensitive curricula focused on behavioral de-escalation techniques, trauma-informed care, and psychopharmacology. Our own residency program created a 2-week mental health rotation13 that includes rotating with outpatient mental health providers and our hospital’s behavioral response team, a group of trauma-informed responders for behavioral emergencies. Similar training should be available for nursing and other allied health professionals, who are often the first responders to behavioral escalations.13

INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND CLINICAL PRACTICES

Ideally, patients requiring higher-intensity psychiatric care would be referred to specialized pediatric behavioral health urgent care centers so their conditions can be adequately evaluated and addressed by staff trained in psychiatric management and in therapeutic environments. We believe all providers caring for children with mental health needs should be trained in basic, but core, behavioral health and de-escalation competencies, including specialized training for children with comorbid medical and neurodevelopmental diagnoses, such as autism. These centers should have specific beds for young children and those with developmental or complex care needs, and services should be available in numerous languages and levels of health literacy to allow all families to participate in their child’s care. At the same time, even nonpsychiatric EDs and inpatient units should commit resources to developing a maximally therapeutic environment, including allowing adjunctive services such as child life services, group therapy, and pet and music therapy, and create environments that support, rather than disrupt, normal routines.

HEALTH SYSTEMS REFORM AND ADVOCACY

Underpinning all the above innovations are changes to our healthcare payment system and provider networks, including the need for insurance coverage and payment parity for behavioral health, to ensure care is not only accessible but affordable. Additionally, for durable change, we need more than just education—we need coalition building and advocacy. Many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have begun this work, which we must all continue.14 Bringing in diverse partners, including health systems, providers, educators, hospital administrators, payors, elected officials, and communities, will prioritize children’s needs and create a more ideal pediatric behavioral healthcare system.15

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire need for comprehensive mental healthcare in the United States, a need that existed before the pandemic and will persist in a more fragile state long after it ends. Our hope is that the pandemic serves as the catalyst necessary to promote the magnitude of investments and stakeholder buy-in necessary to improve pediatric mental health and engender a radical redesign of our behavioral healthcare system. Our patients are counting on us to act. Together, we can build a system that ensures that the kids will be alright.

†Patient details have been changed for patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Perdomo, MD, Amara Azubuike, JD, and Josh Greenberg, JD, for reading and providing feedback on earlier versions of this work.

1. “This is a crisis”: mom whose son has boarded 33 days for psych bed calls for state action. WBUR News. Updated March 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/26/mental-health-boarding-hospitals

2. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813-824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

3. Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005-2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-030692

4. Cloutier RL, Marshaall R. A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:776-777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008

5. Schoenberg S. Lack of mental health beds means long ER waits. CommonWealth Magazine. April 15, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://commonwealthmagazine.org/health-care/lack-of-mental-health-beds-means-long-er-waits/

6. Jolicoeur L, Mullins L. Mass. physicians call on state to address ER “boarding” of patients awaiting admission. WBUR News. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/02/emergency-department-er-inpatient-beds-boarding

7. Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533

8. Impact of COVID-19 on the Massachusetts Health Care System: Interim Report. Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. April 2021. Accessed September 25, 2021. www.mass.gov/doc/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-massachusetts-health-care-system-interim-report/download

9. Foster AA, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Hoffmann JA, Hudgins JD. Pharmacologic restraint use during mental health visits in pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2021;236:276-283.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.027

10. Brown NM, Brown SN, Briggs RD, Germán M, Belamarich PF, Oyeku SO. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):349-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013

11. Harper K, Ryberg R, Temkin D. Black students and students with disabilities remain more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions, despite overall declines. Child Trends. April 29, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.childtrends.org/publications/black-students-disabilities-out-of-school-suspensions

12. Whitaker A, Torres-Guillén S, Morton M, et al. Cops and no counselors: how the lack of school mental health staff is harming students. American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed August 6, 2021. www.aclu.org/report/cops-and-no-counselors

13. Education. Boston Combined Residence Program. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://msbcrp.wpengine.com/program/education/

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Interim guidance on supporting the emotional and behavioral health needs of children, adolescents, and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated July 28, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. http://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/interim-guidance-on-supporting-the-emotional-and-behavioral-health-needs-of-children-adolescents-and-families-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

15. Advocacy. Children’s Mental Health Campaign. Accessed August 4, 2021. https://childrensmentalhealthcampaign.org/advocacy

1. “This is a crisis”: mom whose son has boarded 33 days for psych bed calls for state action. WBUR News. Updated March 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/26/mental-health-boarding-hospitals

2. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813-824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

3. Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005-2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-030692

4. Cloutier RL, Marshaall R. A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:776-777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008

5. Schoenberg S. Lack of mental health beds means long ER waits. CommonWealth Magazine. April 15, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://commonwealthmagazine.org/health-care/lack-of-mental-health-beds-means-long-er-waits/

6. Jolicoeur L, Mullins L. Mass. physicians call on state to address ER “boarding” of patients awaiting admission. WBUR News. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/02/emergency-department-er-inpatient-beds-boarding

7. Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533

8. Impact of COVID-19 on the Massachusetts Health Care System: Interim Report. Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. April 2021. Accessed September 25, 2021. www.mass.gov/doc/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-massachusetts-health-care-system-interim-report/download

9. Foster AA, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Hoffmann JA, Hudgins JD. Pharmacologic restraint use during mental health visits in pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2021;236:276-283.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.027

10. Brown NM, Brown SN, Briggs RD, Germán M, Belamarich PF, Oyeku SO. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):349-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013

11. Harper K, Ryberg R, Temkin D. Black students and students with disabilities remain more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions, despite overall declines. Child Trends. April 29, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.childtrends.org/publications/black-students-disabilities-out-of-school-suspensions

12. Whitaker A, Torres-Guillén S, Morton M, et al. Cops and no counselors: how the lack of school mental health staff is harming students. American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed August 6, 2021. www.aclu.org/report/cops-and-no-counselors

13. Education. Boston Combined Residence Program. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://msbcrp.wpengine.com/program/education/

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Interim guidance on supporting the emotional and behavioral health needs of children, adolescents, and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated July 28, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. http://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/interim-guidance-on-supporting-the-emotional-and-behavioral-health-needs-of-children-adolescents-and-families-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

15. Advocacy. Children’s Mental Health Campaign. Accessed August 4, 2021. https://childrensmentalhealthcampaign.org/advocacy

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine