User login

Lessons Learned From the Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network: A Transdisciplinary Virtual Collaboration Addressing Health System Fragmentation and Disparity During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged in March 2020 in the United States, it was clear that severe COVID-19 and rates of hospitalization were much higher in adults than in children.1 Pediatric facilities grappled with how to leverage empty beds and other underutilized human, clinical, and material resources to offset the overflowing adult facilities.2,3 Pediatricians agonized about how to identify adult patients for whom they could provide safe and effective care, not only as individual clinicians, but also with adequate support from their local pediatric facility and health system.

Maria* (*name changed) was a young adult whose experience with her local health system highlighted common and addressable issues that arose when pediatric facilities aimed to care for adult populations. Adult hospitals were already above capacity caring for acutely ill patients with COVID-19, and a local freestanding children’s hospital offered to offload young adult patients up to age 30 years. Maria, a 26-year-old, had just been transferred from an adult emergency department (ED) to the children’s hospital ED for management of postoperative pain after a recent appendectomy. There was concern for possible abscess formation, but no evidence of sepsis. During his oral presentation, a pediatric resident in the ED reported, “This patient has a history of drug abuse and should not be admitted to a children’s hospital. She has been demanding pain meds and I feel she would be better served at the adult hospital.”

At the intersection of these seemingly impossible questions, dually trained internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds) physicians had a unique vantage point, as they were accustomed to bridging the divide between adult and pediatric medicine in their practices.

As POPCoRN members shared their challenges and institutional learnings, common themes were identified, such as management of intubated patients in non–intensive care unit (ICU) spaces; gaps in staffing with redeployment of residents and hospitalists; and dissemination of education, such as Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) webinars to frontline staff.

IDENTIFY THE “CORRECT” PATIENT POPULATION, BUT DO NOT LET PERFECTION BE A BARRIER TO PROGRESS

Many pediatric facilities reported perseveration over the adult age cutoff accepted to the pediatric facility, only to realize the initial arbitrary age cutoff usually did not encompass enough patients to benefit local adult health systems. Using only strict age cutoffs also created an unnecessary barrier to accepting otherwise appropriate adult patients (eg, adult patient with controlled hypertension and a soft tissue infection).

USE REPETITIVE STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS TO ADAPT TO A RAPIDLY CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

The pandemic response was rapidly evolving and unpredictable. Planning required all affected parties at the table to effectively identify problems and solutions. Clinical and nonclinical groups were critical to planning operational logistics to provide safe care for adults in pediatric facilities.

COMMUNICATE WITH INTENTION AND TRANSPARENCY: WHEN LESS IS NOT MORE

Across care settings and training levels, the power of timely, honest, and transparent communication with leadership echoed throughout the network and could not be overemphasized. The cadence and modes of communication, while established by facility leaders, was best determined by explicitly asking team members for their needs. Often, leaders attempted to avoid communicating abrupt protocol changes to spare their teams additional stress and excessive correspondence. However, POPCoRN members found this approach often increased the perception among staff of a lack of transparency, which exacerbated feelings of discomfort and stress. While other specific examples of communication strategies are included in the POPCoRN guide, network members consistently noted that virtual open forums with leadership at regular intervals allowed teams to ask questions, raise concerns, and share ideas. In addition to open forums, leaders’ written communications regarding local medicolegal limitations and malpractice protection related to adult care should be distributed to staff. In Maria’s case, would provider discomfort and anxiety have been ameliorated with a proactive open forum to discuss the care of adults at the pediatric facility? Would that forum have called attention to staff educational and preparation needs around taking care of adults with a history substance use disorder? If so, this may have added a downstream benefit of decreasing effects of implicit bias amplified by stress.10

MAKE “JUST-IN-TIME” RESOURCES AVAILABLE FOR PEDIATRICIANS CARING FOR ADULT PATIENTS

DESIGN AN EMERGENCY RESPONSE SYSTEM FOR ADULT PATIENTS IN PEDIATRIC FACILITIES

CONCLUSION

Acknowledgments

Collaborators: All the collaborating authors listed below have contributed to the guide available in the appendix of the online version of this article, “Lessons Learned From COVID-19: A Practical Guide for Pediatric Facility Preparedness and Repurposing.” All the authors have provided consent to be listed.

Francisco Alvarez, MD, Stanford, California; Elizabeth Boggs, MD, MS, Aurora, Colorado; Rachel Boykan, MD, Stony Brook, New York; Alicia Caldwell, MD, Cincinnati, Ohio; Maryanne M. Chumpia, MD, MS, Torrance, California; Katharine N Clouser, MD, Hackensack, New Jersey; Alexandra L Coria, MD, Brooklyn, New York; Clare C Crosh, DO, Cincinnati, Ohio; Magna Dias, MD, Bridgeport, Connecticut; Laura N El-Hage, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Jeff Foti, MD, Seattle, Washington; Mirna Giordano, MD, New York, New York; Sheena Gupta, MD, MBA, Evanston, Illinois; Laura Nell Hodo, MD, New York, New York; Ashley Jenkins, MD, MS, Rochester, New York; Anika Kumar, MD, Cleveland, Ohio; Merlin C Lowe, MD, Tuscon, Arizona; Brittany Middleton, MD, Pasadena, California; Sage Myers, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Anik Patel, MD, Salt Lake City, Utah; Leah Ratner, MD, MS, Boston, Massachusetts; Shela Sridhar, MD, MPH, Boston, Massachusetts; Nathan Stehouwer, MD, Cleveland, Ohio; Julie Sylvester, DO, Mount Kisco, New York; Dava Szalda, MD, MSHP, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Heather Toth, MD, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Krista Tuomela, MD, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ronald Williams, MD, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

1. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

2. Osborn R, Doolittle B, Loyal J. When pediatric hospitalists took care of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(1):e15-e18. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-001040

3. Yager PH, Whalen KA, Cummings BM. Repurposing a pediatric ICU for adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):e80. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2014819

4. Conway-Habes EE, Herbst BF Jr, Herbst LA, et al. Using quality improvement to introduce and standardize the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) for adult inpatients at a children’s hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(3):156-163. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0117

5. Kinnear B, O’Toole JK. Care of adults in children’s hospitals: acknowledging the aging elephant in the room. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(12):1081-1082. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2215

6. Szalda D, Steinway C, Greenberg A, et al. Developing a hospital-wide transition program for young adults with medical complexity. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(4):476-482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.008

7. Jenkins A, Ratner L, Caldwell A, Sharma N, Uluer A, White C. Children’s hospitals caring for adults during a pandemic: pragmatic considerations and approaches. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):311-313. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3432

8. Botwinick L, Bisognano M, Haraden C. Leadership Guide to Patient Safety. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2006. Accessed January 20, 2021. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/LeadershipGuidetoPatientSafetyWhitePaper.aspx

9. Essien UR, Eneanya ND, Crews DC. Prioritizing equity in a time of scarcity: the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2760-2762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05976-y

10. Yu R. Stress potentiates decision biases: a stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model. Neurobiol Stress. 2016;3:83-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.12.006

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged in March 2020 in the United States, it was clear that severe COVID-19 and rates of hospitalization were much higher in adults than in children.1 Pediatric facilities grappled with how to leverage empty beds and other underutilized human, clinical, and material resources to offset the overflowing adult facilities.2,3 Pediatricians agonized about how to identify adult patients for whom they could provide safe and effective care, not only as individual clinicians, but also with adequate support from their local pediatric facility and health system.

Maria* (*name changed) was a young adult whose experience with her local health system highlighted common and addressable issues that arose when pediatric facilities aimed to care for adult populations. Adult hospitals were already above capacity caring for acutely ill patients with COVID-19, and a local freestanding children’s hospital offered to offload young adult patients up to age 30 years. Maria, a 26-year-old, had just been transferred from an adult emergency department (ED) to the children’s hospital ED for management of postoperative pain after a recent appendectomy. There was concern for possible abscess formation, but no evidence of sepsis. During his oral presentation, a pediatric resident in the ED reported, “This patient has a history of drug abuse and should not be admitted to a children’s hospital. She has been demanding pain meds and I feel she would be better served at the adult hospital.”

At the intersection of these seemingly impossible questions, dually trained internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds) physicians had a unique vantage point, as they were accustomed to bridging the divide between adult and pediatric medicine in their practices.

As POPCoRN members shared their challenges and institutional learnings, common themes were identified, such as management of intubated patients in non–intensive care unit (ICU) spaces; gaps in staffing with redeployment of residents and hospitalists; and dissemination of education, such as Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) webinars to frontline staff.

IDENTIFY THE “CORRECT” PATIENT POPULATION, BUT DO NOT LET PERFECTION BE A BARRIER TO PROGRESS

Many pediatric facilities reported perseveration over the adult age cutoff accepted to the pediatric facility, only to realize the initial arbitrary age cutoff usually did not encompass enough patients to benefit local adult health systems. Using only strict age cutoffs also created an unnecessary barrier to accepting otherwise appropriate adult patients (eg, adult patient with controlled hypertension and a soft tissue infection).

USE REPETITIVE STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS TO ADAPT TO A RAPIDLY CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

The pandemic response was rapidly evolving and unpredictable. Planning required all affected parties at the table to effectively identify problems and solutions. Clinical and nonclinical groups were critical to planning operational logistics to provide safe care for adults in pediatric facilities.

COMMUNICATE WITH INTENTION AND TRANSPARENCY: WHEN LESS IS NOT MORE

Across care settings and training levels, the power of timely, honest, and transparent communication with leadership echoed throughout the network and could not be overemphasized. The cadence and modes of communication, while established by facility leaders, was best determined by explicitly asking team members for their needs. Often, leaders attempted to avoid communicating abrupt protocol changes to spare their teams additional stress and excessive correspondence. However, POPCoRN members found this approach often increased the perception among staff of a lack of transparency, which exacerbated feelings of discomfort and stress. While other specific examples of communication strategies are included in the POPCoRN guide, network members consistently noted that virtual open forums with leadership at regular intervals allowed teams to ask questions, raise concerns, and share ideas. In addition to open forums, leaders’ written communications regarding local medicolegal limitations and malpractice protection related to adult care should be distributed to staff. In Maria’s case, would provider discomfort and anxiety have been ameliorated with a proactive open forum to discuss the care of adults at the pediatric facility? Would that forum have called attention to staff educational and preparation needs around taking care of adults with a history substance use disorder? If so, this may have added a downstream benefit of decreasing effects of implicit bias amplified by stress.10

MAKE “JUST-IN-TIME” RESOURCES AVAILABLE FOR PEDIATRICIANS CARING FOR ADULT PATIENTS

DESIGN AN EMERGENCY RESPONSE SYSTEM FOR ADULT PATIENTS IN PEDIATRIC FACILITIES

CONCLUSION

Acknowledgments

Collaborators: All the collaborating authors listed below have contributed to the guide available in the appendix of the online version of this article, “Lessons Learned From COVID-19: A Practical Guide for Pediatric Facility Preparedness and Repurposing.” All the authors have provided consent to be listed.

Francisco Alvarez, MD, Stanford, California; Elizabeth Boggs, MD, MS, Aurora, Colorado; Rachel Boykan, MD, Stony Brook, New York; Alicia Caldwell, MD, Cincinnati, Ohio; Maryanne M. Chumpia, MD, MS, Torrance, California; Katharine N Clouser, MD, Hackensack, New Jersey; Alexandra L Coria, MD, Brooklyn, New York; Clare C Crosh, DO, Cincinnati, Ohio; Magna Dias, MD, Bridgeport, Connecticut; Laura N El-Hage, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Jeff Foti, MD, Seattle, Washington; Mirna Giordano, MD, New York, New York; Sheena Gupta, MD, MBA, Evanston, Illinois; Laura Nell Hodo, MD, New York, New York; Ashley Jenkins, MD, MS, Rochester, New York; Anika Kumar, MD, Cleveland, Ohio; Merlin C Lowe, MD, Tuscon, Arizona; Brittany Middleton, MD, Pasadena, California; Sage Myers, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Anik Patel, MD, Salt Lake City, Utah; Leah Ratner, MD, MS, Boston, Massachusetts; Shela Sridhar, MD, MPH, Boston, Massachusetts; Nathan Stehouwer, MD, Cleveland, Ohio; Julie Sylvester, DO, Mount Kisco, New York; Dava Szalda, MD, MSHP, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Heather Toth, MD, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Krista Tuomela, MD, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ronald Williams, MD, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged in March 2020 in the United States, it was clear that severe COVID-19 and rates of hospitalization were much higher in adults than in children.1 Pediatric facilities grappled with how to leverage empty beds and other underutilized human, clinical, and material resources to offset the overflowing adult facilities.2,3 Pediatricians agonized about how to identify adult patients for whom they could provide safe and effective care, not only as individual clinicians, but also with adequate support from their local pediatric facility and health system.

Maria* (*name changed) was a young adult whose experience with her local health system highlighted common and addressable issues that arose when pediatric facilities aimed to care for adult populations. Adult hospitals were already above capacity caring for acutely ill patients with COVID-19, and a local freestanding children’s hospital offered to offload young adult patients up to age 30 years. Maria, a 26-year-old, had just been transferred from an adult emergency department (ED) to the children’s hospital ED for management of postoperative pain after a recent appendectomy. There was concern for possible abscess formation, but no evidence of sepsis. During his oral presentation, a pediatric resident in the ED reported, “This patient has a history of drug abuse and should not be admitted to a children’s hospital. She has been demanding pain meds and I feel she would be better served at the adult hospital.”

At the intersection of these seemingly impossible questions, dually trained internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds) physicians had a unique vantage point, as they were accustomed to bridging the divide between adult and pediatric medicine in their practices.

As POPCoRN members shared their challenges and institutional learnings, common themes were identified, such as management of intubated patients in non–intensive care unit (ICU) spaces; gaps in staffing with redeployment of residents and hospitalists; and dissemination of education, such as Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) webinars to frontline staff.

IDENTIFY THE “CORRECT” PATIENT POPULATION, BUT DO NOT LET PERFECTION BE A BARRIER TO PROGRESS

Many pediatric facilities reported perseveration over the adult age cutoff accepted to the pediatric facility, only to realize the initial arbitrary age cutoff usually did not encompass enough patients to benefit local adult health systems. Using only strict age cutoffs also created an unnecessary barrier to accepting otherwise appropriate adult patients (eg, adult patient with controlled hypertension and a soft tissue infection).

USE REPETITIVE STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS TO ADAPT TO A RAPIDLY CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

The pandemic response was rapidly evolving and unpredictable. Planning required all affected parties at the table to effectively identify problems and solutions. Clinical and nonclinical groups were critical to planning operational logistics to provide safe care for adults in pediatric facilities.

COMMUNICATE WITH INTENTION AND TRANSPARENCY: WHEN LESS IS NOT MORE

Across care settings and training levels, the power of timely, honest, and transparent communication with leadership echoed throughout the network and could not be overemphasized. The cadence and modes of communication, while established by facility leaders, was best determined by explicitly asking team members for their needs. Often, leaders attempted to avoid communicating abrupt protocol changes to spare their teams additional stress and excessive correspondence. However, POPCoRN members found this approach often increased the perception among staff of a lack of transparency, which exacerbated feelings of discomfort and stress. While other specific examples of communication strategies are included in the POPCoRN guide, network members consistently noted that virtual open forums with leadership at regular intervals allowed teams to ask questions, raise concerns, and share ideas. In addition to open forums, leaders’ written communications regarding local medicolegal limitations and malpractice protection related to adult care should be distributed to staff. In Maria’s case, would provider discomfort and anxiety have been ameliorated with a proactive open forum to discuss the care of adults at the pediatric facility? Would that forum have called attention to staff educational and preparation needs around taking care of adults with a history substance use disorder? If so, this may have added a downstream benefit of decreasing effects of implicit bias amplified by stress.10

MAKE “JUST-IN-TIME” RESOURCES AVAILABLE FOR PEDIATRICIANS CARING FOR ADULT PATIENTS

DESIGN AN EMERGENCY RESPONSE SYSTEM FOR ADULT PATIENTS IN PEDIATRIC FACILITIES

CONCLUSION

Acknowledgments

Collaborators: All the collaborating authors listed below have contributed to the guide available in the appendix of the online version of this article, “Lessons Learned From COVID-19: A Practical Guide for Pediatric Facility Preparedness and Repurposing.” All the authors have provided consent to be listed.

Francisco Alvarez, MD, Stanford, California; Elizabeth Boggs, MD, MS, Aurora, Colorado; Rachel Boykan, MD, Stony Brook, New York; Alicia Caldwell, MD, Cincinnati, Ohio; Maryanne M. Chumpia, MD, MS, Torrance, California; Katharine N Clouser, MD, Hackensack, New Jersey; Alexandra L Coria, MD, Brooklyn, New York; Clare C Crosh, DO, Cincinnati, Ohio; Magna Dias, MD, Bridgeport, Connecticut; Laura N El-Hage, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Jeff Foti, MD, Seattle, Washington; Mirna Giordano, MD, New York, New York; Sheena Gupta, MD, MBA, Evanston, Illinois; Laura Nell Hodo, MD, New York, New York; Ashley Jenkins, MD, MS, Rochester, New York; Anika Kumar, MD, Cleveland, Ohio; Merlin C Lowe, MD, Tuscon, Arizona; Brittany Middleton, MD, Pasadena, California; Sage Myers, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Anik Patel, MD, Salt Lake City, Utah; Leah Ratner, MD, MS, Boston, Massachusetts; Shela Sridhar, MD, MPH, Boston, Massachusetts; Nathan Stehouwer, MD, Cleveland, Ohio; Julie Sylvester, DO, Mount Kisco, New York; Dava Szalda, MD, MSHP, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Heather Toth, MD, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Krista Tuomela, MD, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ronald Williams, MD, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

1. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

2. Osborn R, Doolittle B, Loyal J. When pediatric hospitalists took care of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(1):e15-e18. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-001040

3. Yager PH, Whalen KA, Cummings BM. Repurposing a pediatric ICU for adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):e80. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2014819

4. Conway-Habes EE, Herbst BF Jr, Herbst LA, et al. Using quality improvement to introduce and standardize the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) for adult inpatients at a children’s hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(3):156-163. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0117

5. Kinnear B, O’Toole JK. Care of adults in children’s hospitals: acknowledging the aging elephant in the room. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(12):1081-1082. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2215

6. Szalda D, Steinway C, Greenberg A, et al. Developing a hospital-wide transition program for young adults with medical complexity. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(4):476-482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.008

7. Jenkins A, Ratner L, Caldwell A, Sharma N, Uluer A, White C. Children’s hospitals caring for adults during a pandemic: pragmatic considerations and approaches. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):311-313. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3432

8. Botwinick L, Bisognano M, Haraden C. Leadership Guide to Patient Safety. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2006. Accessed January 20, 2021. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/LeadershipGuidetoPatientSafetyWhitePaper.aspx

9. Essien UR, Eneanya ND, Crews DC. Prioritizing equity in a time of scarcity: the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2760-2762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05976-y

10. Yu R. Stress potentiates decision biases: a stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model. Neurobiol Stress. 2016;3:83-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.12.006

1. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

2. Osborn R, Doolittle B, Loyal J. When pediatric hospitalists took care of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(1):e15-e18. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-001040

3. Yager PH, Whalen KA, Cummings BM. Repurposing a pediatric ICU for adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):e80. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2014819

4. Conway-Habes EE, Herbst BF Jr, Herbst LA, et al. Using quality improvement to introduce and standardize the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) for adult inpatients at a children’s hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(3):156-163. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0117

5. Kinnear B, O’Toole JK. Care of adults in children’s hospitals: acknowledging the aging elephant in the room. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(12):1081-1082. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2215

6. Szalda D, Steinway C, Greenberg A, et al. Developing a hospital-wide transition program for young adults with medical complexity. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(4):476-482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.008

7. Jenkins A, Ratner L, Caldwell A, Sharma N, Uluer A, White C. Children’s hospitals caring for adults during a pandemic: pragmatic considerations and approaches. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):311-313. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3432

8. Botwinick L, Bisognano M, Haraden C. Leadership Guide to Patient Safety. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2006. Accessed January 20, 2021. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/LeadershipGuidetoPatientSafetyWhitePaper.aspx

9. Essien UR, Eneanya ND, Crews DC. Prioritizing equity in a time of scarcity: the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2760-2762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05976-y

10. Yu R. Stress potentiates decision biases: a stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model. Neurobiol Stress. 2016;3:83-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.12.006

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Designing Quality Programs for Rural Hospitals

Population-based hospital payments provide incentives to reduce unnecessary healthcare use and a mechanism to finance population health investments. For hospitals, these payments provide stable revenue and flexibility in exchange for increased financial risk. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced fee-for-service revenues, which has spurred provider interest in population-based payments, particularly from cash-strapped rural hospitals.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the launch of the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model to test whether up-front, population-based payments improve access to high-quality care in rural communities and protect the financial stability of rural providers. This model follows the ongoing Pennsylvania Rural Health Model (PARHM), which offers similar payments to Pennsylvania’s rural hospitals. Prospective population-based hospital reimbursement appears to have helped Maryland’s hospitals survive the financial stress of the COVID-19 pandemic,1 and it is likely that the PARHM did the same for rural hospitals in Pennsylvania. Both the PARHM and the CHART Model place quality measurement and improvement at the core of payment reform, and for good reason. Capitation generates incentives for care stinting; linking prospective payments to quality measurement helps to ensure accountability. However, measuring the quality of rural healthcare is challenging. Rural health is different: Hospital size, payment mechanisms, and community health priorities are all distinct from those of metropolitan areas, which is why CMS exempts Critical Access Hospitals from Medicare’s core quality programs. Rural quality reporting programs could be established that address the unique aspects of rural healthcare.

As designers (JEF, DTL) of, and an advisor (ALS) for, a proposed pay-for-performance (P4P) program for the PARHM,2 we identified three central challenges in constructing and implementing P4P programs for rural hospitals, along with potential solutions. We hope that the lessons we learned can inform similar policy efforts.

First, many rural hospitals serve as stewards of community health resources. While metropolitan hospital systems can make targeted investments in population health, assigning accountability for health outcomes is challenging in cities where geographically overlapping provider systems compete for patients. In contrast, a rural hospital system with few or no competing providers is more naturally accountable for community health outcomes, especially if it owns most ambulatory clinics in its community. P4P programs could therefore reward rural hospitals for improving healthcare quality or health outcomes within their catchment areas. Like an accountable care organization (ACO), a rural hospital or hospital-based health system could be held accountable for appropriate screening for, and treatment of, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or asthma, even without a network of community-based primary care providers that ACOs usually possess. Participants in the CHART Model’s Community Transformation Track, for example, select three community-level population health measures from four domains: substance use, chronic conditions, maternal health, and prevention. Accountability for community health outcomes is increasingly feasible because many larger rural hospitals have merged or been acquired.3

Second, small rural hospital patient volumes obscure the signal of true quality with statistical noise. Many common quality indicators, like risk-standardized mortality rates, are unreliable in rural settings with low patient volumes; in 2012-2013, the mean rural hospital daily census was seven inpatients.4,5 Payers and regulators have addressed this challenge by exempting rural hospitals from quality-reporting programs or by employing statistical techniques that diminish incentives to invest in improvement. CMS, for example, uses “shrinkage” estimators that adjust a hospital’s quality score toward a program-wide average, which makes it difficult to detect and reward performance improvement.4 Instead, rural P4P programs should use measures that are resistant to low patient volumes, such as the Measure Application Partnership’s (MAP) Core Set of Rural-Relevant Measures.6 Low volume–resistant measures include process and population-health outcome measures with naturally large denominators (eg, medication reconciliation), structural measures for which sample size is irrelevant (eg, nurse staffing ratios), and qualitative assessments of hospital adherence to best practices. CMS and other measure developers should also prioritize the creation of other rural-relevant, cross-cutting, low volume–resistant measures, like avoidance of deliriogenic medications in the elderly or initiation of treatment for substance use disorders, in consultation with rural stakeholders and the MAP Rural Health Workgroup. When extensive measurement noise is inevitable, public and private policymakers should eschew downside risk in rural P4P contracts.

Third, many rural hospitals have limited resources for measurement and improvement.7 While many well-resourced community hospitals have dedicated quality departments, quality directors in rural hospitals often have at least one other full-time job. Well-intentioned exemptions from P4P programs have left rural hospitals with limited experience with basic data collection and reporting, a handicap compounded by redundant and misaligned payor quality reporting requirements. To engage rural hospitals in quality improvement work, payors should coordinate to make participation in rural P4P programs as easy as possible. The adoption of a locally aligned set of healthcare quality measures by all payors in a region, like the PARHM’s proposed “all-payer quality program,” could substantially reduce administrative burden and motivate rural hospitals to enhance patient care and improve community health. In the CHART Model’s Community Transformation Track, for example, all public and private participating payers in each region must report on six quality measures: inpatient and emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions, hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmissions, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care survey, as well as three community-chosen measures from the domains of substance use, maternal health, and prevention.8 As with all P4P programs, rural P4P programs should focus on a small number of meaningful measures, such as functional and clinical outcomes, complications, and patient experience, and feature relatively large rewards for improvement.9 The National Quality Forum recommends that rural programs avoid downside risk, reward improvement as well as achievement, and permit virtual provider groups.10 We would add that programs in rural communities ought to pair economic rewards with social recognition and comparison, offer technical assistance and opportunities for shared learning, and account for social as well as medical risk.

Many challenges to the adoption of rural P4P programs have been targeted through multi-stakeholder collaborations like the PARHM. Careful allocation of technical assistance resources may help address barriers such as comparing the performance of heterogeneous rural hospitals that vary in characteristics like size, affiliation with large health systems, or integration of ambulatory care services, which may affect hospital measurement capabilities and performance. Quality improvement efforts could be further bolstered through direct allocation of funds to the creation of virtual shared learning platforms, and by providing performance bonuses to groups of small hospitals that elect to engage in shared reporting.

The stakes are high for designing robust quality programs for rural hospitals. Although one in five Americans rely on them for healthcare, their rate of closure has accelerated in the past decade.11 CMS has made it clear that a sustainable system for financing rural health must be built around a commitment to quality measurement and improvement. While some rural provider organizations might be best served by participating in voluntary rural health networks and preexisting federal programs like the Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project, they should also have the opportunity to accept payments tied to quality, especially as growing numbers of rural hospitals are absorbed into larger healthcare systems. Adopting aligned sets of reliable and meaningful quality measures alongside population-based payments will help to create a sustainable future for rural hospitals.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mark Friedberg, MD, MPP, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

1. Peterson CL, Schumacher DN. How Maryland’s Total Cost of Care Model has helped hospitals manage the COVID-19 stress test. Health Affairs blog. October 7, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hblog20201005.677034/full/

2. Herzog MB, Fried JE, Liebers DT, MacKinney AC. Development of an all-payer quality program for the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model. J Rural Health. Published online December 4, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12547

3. Williams D Jr, Reiter KL, Pink GH, Holmes GM, Song PH. Rural hospital mergers increased between 2005 and 2016—what did those hospitals look like? Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020935666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958020935666

4. Schwartz AL. Accuracy vs. incentives: a tradeoff for performance measurement. Am J Health Econ. Accepted February 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1086/714374

5. Freeman V, Thompson K, Howard HA, et al. The 21st Century Rural Hospital: A Chart Book. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. March 2015. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/product/21st-century-rural-hospital-chart-book/https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/projects/north-carolina-rural-health-research-and-policy-analysis-center/publications/

6. National Quality Forum. A core set of rural-relevant measures and measuring and improving access to care: 2018 recommendations from the MAP Rural Health Workgroup. August 31, 2018.

7. US Government Accountability Office. Medicare value-based payment models: participation challenges and available assistance for small and rural practices. December 9, 2016. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-55

8. US Department of Health & Human Services. Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART). Funding Opportunity Number: CMS-2G2-21-001. March 5, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=329062

9. Jha AK. Time to get serious about pay for performance. JAMA. 2013;309(4):347-348. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.196646

10. National Quality Forum. Performance measurement for rural low-volume providers. September 14, 2015. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/09/Rural_Health_Final_Report.aspx

11. US Government Accountability Office. Rural hospital closures: number and characteristics of affected hospitals and contributing factors. GAO-18-634. August 29, 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-634.pdf

Population-based hospital payments provide incentives to reduce unnecessary healthcare use and a mechanism to finance population health investments. For hospitals, these payments provide stable revenue and flexibility in exchange for increased financial risk. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced fee-for-service revenues, which has spurred provider interest in population-based payments, particularly from cash-strapped rural hospitals.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the launch of the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model to test whether up-front, population-based payments improve access to high-quality care in rural communities and protect the financial stability of rural providers. This model follows the ongoing Pennsylvania Rural Health Model (PARHM), which offers similar payments to Pennsylvania’s rural hospitals. Prospective population-based hospital reimbursement appears to have helped Maryland’s hospitals survive the financial stress of the COVID-19 pandemic,1 and it is likely that the PARHM did the same for rural hospitals in Pennsylvania. Both the PARHM and the CHART Model place quality measurement and improvement at the core of payment reform, and for good reason. Capitation generates incentives for care stinting; linking prospective payments to quality measurement helps to ensure accountability. However, measuring the quality of rural healthcare is challenging. Rural health is different: Hospital size, payment mechanisms, and community health priorities are all distinct from those of metropolitan areas, which is why CMS exempts Critical Access Hospitals from Medicare’s core quality programs. Rural quality reporting programs could be established that address the unique aspects of rural healthcare.

As designers (JEF, DTL) of, and an advisor (ALS) for, a proposed pay-for-performance (P4P) program for the PARHM,2 we identified three central challenges in constructing and implementing P4P programs for rural hospitals, along with potential solutions. We hope that the lessons we learned can inform similar policy efforts.

First, many rural hospitals serve as stewards of community health resources. While metropolitan hospital systems can make targeted investments in population health, assigning accountability for health outcomes is challenging in cities where geographically overlapping provider systems compete for patients. In contrast, a rural hospital system with few or no competing providers is more naturally accountable for community health outcomes, especially if it owns most ambulatory clinics in its community. P4P programs could therefore reward rural hospitals for improving healthcare quality or health outcomes within their catchment areas. Like an accountable care organization (ACO), a rural hospital or hospital-based health system could be held accountable for appropriate screening for, and treatment of, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or asthma, even without a network of community-based primary care providers that ACOs usually possess. Participants in the CHART Model’s Community Transformation Track, for example, select three community-level population health measures from four domains: substance use, chronic conditions, maternal health, and prevention. Accountability for community health outcomes is increasingly feasible because many larger rural hospitals have merged or been acquired.3

Second, small rural hospital patient volumes obscure the signal of true quality with statistical noise. Many common quality indicators, like risk-standardized mortality rates, are unreliable in rural settings with low patient volumes; in 2012-2013, the mean rural hospital daily census was seven inpatients.4,5 Payers and regulators have addressed this challenge by exempting rural hospitals from quality-reporting programs or by employing statistical techniques that diminish incentives to invest in improvement. CMS, for example, uses “shrinkage” estimators that adjust a hospital’s quality score toward a program-wide average, which makes it difficult to detect and reward performance improvement.4 Instead, rural P4P programs should use measures that are resistant to low patient volumes, such as the Measure Application Partnership’s (MAP) Core Set of Rural-Relevant Measures.6 Low volume–resistant measures include process and population-health outcome measures with naturally large denominators (eg, medication reconciliation), structural measures for which sample size is irrelevant (eg, nurse staffing ratios), and qualitative assessments of hospital adherence to best practices. CMS and other measure developers should also prioritize the creation of other rural-relevant, cross-cutting, low volume–resistant measures, like avoidance of deliriogenic medications in the elderly or initiation of treatment for substance use disorders, in consultation with rural stakeholders and the MAP Rural Health Workgroup. When extensive measurement noise is inevitable, public and private policymakers should eschew downside risk in rural P4P contracts.

Third, many rural hospitals have limited resources for measurement and improvement.7 While many well-resourced community hospitals have dedicated quality departments, quality directors in rural hospitals often have at least one other full-time job. Well-intentioned exemptions from P4P programs have left rural hospitals with limited experience with basic data collection and reporting, a handicap compounded by redundant and misaligned payor quality reporting requirements. To engage rural hospitals in quality improvement work, payors should coordinate to make participation in rural P4P programs as easy as possible. The adoption of a locally aligned set of healthcare quality measures by all payors in a region, like the PARHM’s proposed “all-payer quality program,” could substantially reduce administrative burden and motivate rural hospitals to enhance patient care and improve community health. In the CHART Model’s Community Transformation Track, for example, all public and private participating payers in each region must report on six quality measures: inpatient and emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions, hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmissions, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care survey, as well as three community-chosen measures from the domains of substance use, maternal health, and prevention.8 As with all P4P programs, rural P4P programs should focus on a small number of meaningful measures, such as functional and clinical outcomes, complications, and patient experience, and feature relatively large rewards for improvement.9 The National Quality Forum recommends that rural programs avoid downside risk, reward improvement as well as achievement, and permit virtual provider groups.10 We would add that programs in rural communities ought to pair economic rewards with social recognition and comparison, offer technical assistance and opportunities for shared learning, and account for social as well as medical risk.

Many challenges to the adoption of rural P4P programs have been targeted through multi-stakeholder collaborations like the PARHM. Careful allocation of technical assistance resources may help address barriers such as comparing the performance of heterogeneous rural hospitals that vary in characteristics like size, affiliation with large health systems, or integration of ambulatory care services, which may affect hospital measurement capabilities and performance. Quality improvement efforts could be further bolstered through direct allocation of funds to the creation of virtual shared learning platforms, and by providing performance bonuses to groups of small hospitals that elect to engage in shared reporting.

The stakes are high for designing robust quality programs for rural hospitals. Although one in five Americans rely on them for healthcare, their rate of closure has accelerated in the past decade.11 CMS has made it clear that a sustainable system for financing rural health must be built around a commitment to quality measurement and improvement. While some rural provider organizations might be best served by participating in voluntary rural health networks and preexisting federal programs like the Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project, they should also have the opportunity to accept payments tied to quality, especially as growing numbers of rural hospitals are absorbed into larger healthcare systems. Adopting aligned sets of reliable and meaningful quality measures alongside population-based payments will help to create a sustainable future for rural hospitals.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mark Friedberg, MD, MPP, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Population-based hospital payments provide incentives to reduce unnecessary healthcare use and a mechanism to finance population health investments. For hospitals, these payments provide stable revenue and flexibility in exchange for increased financial risk. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced fee-for-service revenues, which has spurred provider interest in population-based payments, particularly from cash-strapped rural hospitals.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the launch of the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model to test whether up-front, population-based payments improve access to high-quality care in rural communities and protect the financial stability of rural providers. This model follows the ongoing Pennsylvania Rural Health Model (PARHM), which offers similar payments to Pennsylvania’s rural hospitals. Prospective population-based hospital reimbursement appears to have helped Maryland’s hospitals survive the financial stress of the COVID-19 pandemic,1 and it is likely that the PARHM did the same for rural hospitals in Pennsylvania. Both the PARHM and the CHART Model place quality measurement and improvement at the core of payment reform, and for good reason. Capitation generates incentives for care stinting; linking prospective payments to quality measurement helps to ensure accountability. However, measuring the quality of rural healthcare is challenging. Rural health is different: Hospital size, payment mechanisms, and community health priorities are all distinct from those of metropolitan areas, which is why CMS exempts Critical Access Hospitals from Medicare’s core quality programs. Rural quality reporting programs could be established that address the unique aspects of rural healthcare.

As designers (JEF, DTL) of, and an advisor (ALS) for, a proposed pay-for-performance (P4P) program for the PARHM,2 we identified three central challenges in constructing and implementing P4P programs for rural hospitals, along with potential solutions. We hope that the lessons we learned can inform similar policy efforts.

First, many rural hospitals serve as stewards of community health resources. While metropolitan hospital systems can make targeted investments in population health, assigning accountability for health outcomes is challenging in cities where geographically overlapping provider systems compete for patients. In contrast, a rural hospital system with few or no competing providers is more naturally accountable for community health outcomes, especially if it owns most ambulatory clinics in its community. P4P programs could therefore reward rural hospitals for improving healthcare quality or health outcomes within their catchment areas. Like an accountable care organization (ACO), a rural hospital or hospital-based health system could be held accountable for appropriate screening for, and treatment of, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or asthma, even without a network of community-based primary care providers that ACOs usually possess. Participants in the CHART Model’s Community Transformation Track, for example, select three community-level population health measures from four domains: substance use, chronic conditions, maternal health, and prevention. Accountability for community health outcomes is increasingly feasible because many larger rural hospitals have merged or been acquired.3

Second, small rural hospital patient volumes obscure the signal of true quality with statistical noise. Many common quality indicators, like risk-standardized mortality rates, are unreliable in rural settings with low patient volumes; in 2012-2013, the mean rural hospital daily census was seven inpatients.4,5 Payers and regulators have addressed this challenge by exempting rural hospitals from quality-reporting programs or by employing statistical techniques that diminish incentives to invest in improvement. CMS, for example, uses “shrinkage” estimators that adjust a hospital’s quality score toward a program-wide average, which makes it difficult to detect and reward performance improvement.4 Instead, rural P4P programs should use measures that are resistant to low patient volumes, such as the Measure Application Partnership’s (MAP) Core Set of Rural-Relevant Measures.6 Low volume–resistant measures include process and population-health outcome measures with naturally large denominators (eg, medication reconciliation), structural measures for which sample size is irrelevant (eg, nurse staffing ratios), and qualitative assessments of hospital adherence to best practices. CMS and other measure developers should also prioritize the creation of other rural-relevant, cross-cutting, low volume–resistant measures, like avoidance of deliriogenic medications in the elderly or initiation of treatment for substance use disorders, in consultation with rural stakeholders and the MAP Rural Health Workgroup. When extensive measurement noise is inevitable, public and private policymakers should eschew downside risk in rural P4P contracts.

Third, many rural hospitals have limited resources for measurement and improvement.7 While many well-resourced community hospitals have dedicated quality departments, quality directors in rural hospitals often have at least one other full-time job. Well-intentioned exemptions from P4P programs have left rural hospitals with limited experience with basic data collection and reporting, a handicap compounded by redundant and misaligned payor quality reporting requirements. To engage rural hospitals in quality improvement work, payors should coordinate to make participation in rural P4P programs as easy as possible. The adoption of a locally aligned set of healthcare quality measures by all payors in a region, like the PARHM’s proposed “all-payer quality program,” could substantially reduce administrative burden and motivate rural hospitals to enhance patient care and improve community health. In the CHART Model’s Community Transformation Track, for example, all public and private participating payers in each region must report on six quality measures: inpatient and emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions, hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmissions, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care survey, as well as three community-chosen measures from the domains of substance use, maternal health, and prevention.8 As with all P4P programs, rural P4P programs should focus on a small number of meaningful measures, such as functional and clinical outcomes, complications, and patient experience, and feature relatively large rewards for improvement.9 The National Quality Forum recommends that rural programs avoid downside risk, reward improvement as well as achievement, and permit virtual provider groups.10 We would add that programs in rural communities ought to pair economic rewards with social recognition and comparison, offer technical assistance and opportunities for shared learning, and account for social as well as medical risk.

Many challenges to the adoption of rural P4P programs have been targeted through multi-stakeholder collaborations like the PARHM. Careful allocation of technical assistance resources may help address barriers such as comparing the performance of heterogeneous rural hospitals that vary in characteristics like size, affiliation with large health systems, or integration of ambulatory care services, which may affect hospital measurement capabilities and performance. Quality improvement efforts could be further bolstered through direct allocation of funds to the creation of virtual shared learning platforms, and by providing performance bonuses to groups of small hospitals that elect to engage in shared reporting.

The stakes are high for designing robust quality programs for rural hospitals. Although one in five Americans rely on them for healthcare, their rate of closure has accelerated in the past decade.11 CMS has made it clear that a sustainable system for financing rural health must be built around a commitment to quality measurement and improvement. While some rural provider organizations might be best served by participating in voluntary rural health networks and preexisting federal programs like the Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project, they should also have the opportunity to accept payments tied to quality, especially as growing numbers of rural hospitals are absorbed into larger healthcare systems. Adopting aligned sets of reliable and meaningful quality measures alongside population-based payments will help to create a sustainable future for rural hospitals.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mark Friedberg, MD, MPP, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

1. Peterson CL, Schumacher DN. How Maryland’s Total Cost of Care Model has helped hospitals manage the COVID-19 stress test. Health Affairs blog. October 7, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hblog20201005.677034/full/

2. Herzog MB, Fried JE, Liebers DT, MacKinney AC. Development of an all-payer quality program for the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model. J Rural Health. Published online December 4, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12547

3. Williams D Jr, Reiter KL, Pink GH, Holmes GM, Song PH. Rural hospital mergers increased between 2005 and 2016—what did those hospitals look like? Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020935666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958020935666

4. Schwartz AL. Accuracy vs. incentives: a tradeoff for performance measurement. Am J Health Econ. Accepted February 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1086/714374

5. Freeman V, Thompson K, Howard HA, et al. The 21st Century Rural Hospital: A Chart Book. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. March 2015. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/product/21st-century-rural-hospital-chart-book/https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/projects/north-carolina-rural-health-research-and-policy-analysis-center/publications/

6. National Quality Forum. A core set of rural-relevant measures and measuring and improving access to care: 2018 recommendations from the MAP Rural Health Workgroup. August 31, 2018.

7. US Government Accountability Office. Medicare value-based payment models: participation challenges and available assistance for small and rural practices. December 9, 2016. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-55

8. US Department of Health & Human Services. Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART). Funding Opportunity Number: CMS-2G2-21-001. March 5, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=329062

9. Jha AK. Time to get serious about pay for performance. JAMA. 2013;309(4):347-348. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.196646

10. National Quality Forum. Performance measurement for rural low-volume providers. September 14, 2015. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/09/Rural_Health_Final_Report.aspx

11. US Government Accountability Office. Rural hospital closures: number and characteristics of affected hospitals and contributing factors. GAO-18-634. August 29, 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-634.pdf

1. Peterson CL, Schumacher DN. How Maryland’s Total Cost of Care Model has helped hospitals manage the COVID-19 stress test. Health Affairs blog. October 7, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hblog20201005.677034/full/

2. Herzog MB, Fried JE, Liebers DT, MacKinney AC. Development of an all-payer quality program for the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model. J Rural Health. Published online December 4, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12547

3. Williams D Jr, Reiter KL, Pink GH, Holmes GM, Song PH. Rural hospital mergers increased between 2005 and 2016—what did those hospitals look like? Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020935666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958020935666

4. Schwartz AL. Accuracy vs. incentives: a tradeoff for performance measurement. Am J Health Econ. Accepted February 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1086/714374

5. Freeman V, Thompson K, Howard HA, et al. The 21st Century Rural Hospital: A Chart Book. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. March 2015. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/product/21st-century-rural-hospital-chart-book/https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/projects/north-carolina-rural-health-research-and-policy-analysis-center/publications/

6. National Quality Forum. A core set of rural-relevant measures and measuring and improving access to care: 2018 recommendations from the MAP Rural Health Workgroup. August 31, 2018.

7. US Government Accountability Office. Medicare value-based payment models: participation challenges and available assistance for small and rural practices. December 9, 2016. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-55

8. US Department of Health & Human Services. Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART). Funding Opportunity Number: CMS-2G2-21-001. March 5, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=329062

9. Jha AK. Time to get serious about pay for performance. JAMA. 2013;309(4):347-348. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.196646

10. National Quality Forum. Performance measurement for rural low-volume providers. September 14, 2015. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/09/Rural_Health_Final_Report.aspx

11. US Government Accountability Office. Rural hospital closures: number and characteristics of affected hospitals and contributing factors. GAO-18-634. August 29, 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-634.pdf

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Moment vs Movement: Mission-Based Tweeting for Physician Advocacy

“We, the members of the world community of physicians, solemnly commit ourselves to . . . advocate for social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”

— American Medical Association Oath of Professional Responsibility. 1

As individuals and groups spread misinformation on social media platforms, there is a greater need for physician health advocacy.2 We have learned through the COVID-19 pandemic that rapidly evolving information requires public-facing health experts to address misinformation and explain why healthcare providers and experts make certain recommendations.2 Physicians recognize the potential for benefit from crowdsourcing education, positive publicity, and increasing their reach to a larger platform.3

However, despite social media’s need for such expertise and these recognized benefits, many physicians are hesitant to engage on social media, citing lack of time, interest, or the proper skill set to use it effectively.3 Additional barriers may include uncertainty about employer policies, fear of saying something inaccurate or unprofessional, or inadvertently breaching patient privacy.3 While these are valid concerns, a strategic approach to curating a social media presence focuses less on the moments created by provocative tweets and more on the movement the author wishes to amplify. Here, we propose a framework for effective physician advocacy using a strategy we term Mission-Based Tweeting (MBT).

MISSION-BASED TWEETING

Physicians can use Twitter to engage large audiences.4 MBT focuses an individual’s central message by providing a framework upon which to build such engagement.5 The conceptual framework for a meaningful social media strategy through MBT is anchored on the principle that the impact of our Twitter content is more valuable than the number of followers.6 Using this framework, users begin by creating and defining their identity while engaging in meaningful online interactions. Over time, these interactions will lead to generating influence related to their established identity, which can ultimately impact the social micro-society.6 While an individual’s social media impact can be determined and reinforced through MBT, it remains important to know that MBT is not exemplified in one specific tweet, but rather in the body of work shared by an individual that continuously reinforces the mission.

TWEETING FOR THE MOMENT VS FOR THE MOVEMENT: USING MBT FOR ADVOCACY

Advocacy typically involves using one’s voice to publicly support a specific interest. With that in mind, health advocacy can be divided into two categories: (1) agency, which involves advancing the health of individual patients within a system, and (2) activism, which acts to advance the health of communities or populations or change the structure of the healthcare system.7 While many physicians accept agency as part of their day-to-day job, activism is often more difficult. For example, physicians hoping to engage in health advocacy may be unable to travel to their state or federal legislature buildings, or their employers may restrict their ability to interact with elected officials. The emergence of social media and digital technology has lowered these barriers and created more accessible opportunities for physicians to engage in advocacy efforts.

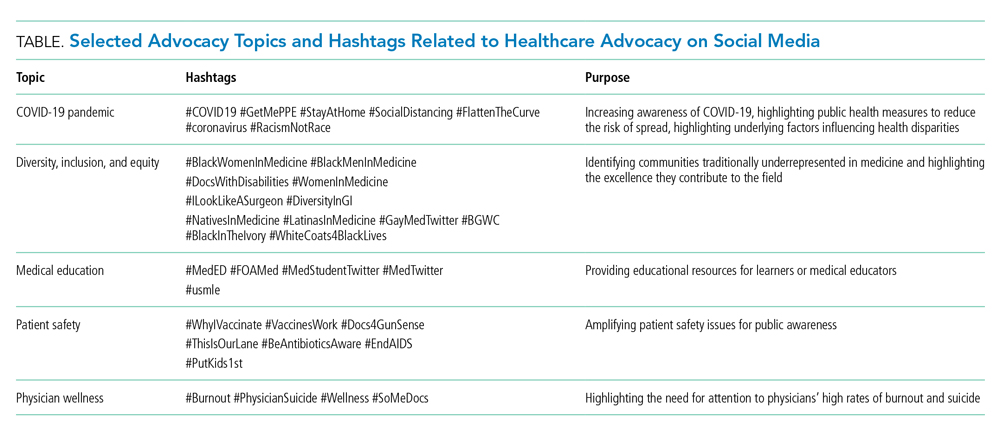

Social media can provide an opportunity for clinicians to engage with other healthcare professionals, creating movements that have far-reaching effects across the healthcare spectrum. These movements, often driven by common hashtags, have expanded greatly beyond their originators’ intent, thus demonstrating the power of social media for healthcare activism (Table).4 Physician advocacy can provide accurate information about medical conditions and treatments, dispel myths that may affect patient care, and draw attention to conditions that impact their ability to provide that care. For instance, physicians and medical students recently used Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic to focus on the real consequences of lack of access to personal protective equipment during the pandemic (Table).8,9 In the past year, physicians have used Twitter to highlight how structural racism perpetuates racial disparities in COVID-19 and to call for action against police brutality and the killing of unarmed Black citizens. Such activism has led to media appearances and even congressional testimony—which has, in turn, provided even larger audiences for clinicians’ advocacy efforts.10 Physicians can also use MBT to advocate for the medical profession. Strategic, mission-based, social media campaigns have focused on including women; Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); doctors with disabilities; and LGBTQ+ physicians in the narrative of what a doctor looks like (Table).11,12

When physicians consider their personal mission statement as it applies to their social media presence, it allows them to connect to something bigger than themselves, while helping guide them away from engagements that do not align with their personal or professional values. In this manner, MBT harnesses an individual’s authenticity and helps build their personal branding, which may ultimately result in more opportunities to advance their mission. In our experience, the constant delivery of mission-based content can even accelerate one’s professional work, help amplify others’ successes and voices, and ultimately lead to more meaningful engagement and activism.

However, it is important to note that there are potential downsides to engaging on social media, particularly for women and BIPOC users. For example, in a recent online survey, almost a quarter of physicians who responded reported personal attacks on social media, with one in six female physicians reporting sexual harassment.13 This risk may increase as an individual’s visibility and reach increase.

DEVELOP YOUR MISSION STATEMENT

To aid in MBT, we have found it useful to define your personal mission statement, which should succinctly describe your core values, the specific population or cause you serve, and your overarching goals or ideals. For example, someone interested in advocating for health justice might have the following mission statement: “To create and support a healthcare workforce and graduate medical education environment that strives for excellence and values Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity as not only important, but necessary, for excellence.”14 Developing a personal mission statement permits more focus in all activities, including clinical, educational, administrative, or scholarship, and allows one to succinctly communicate important values with others.15 Communicating your personal mission statement concisely can improve the quality of your interactions with others and allows you to more precisely define the qualitative and quantitative impact of your social media engagement.

ENGAGING TO AMPLIFY YOUR MISSION

There are several options for creating and delivering effective mission-driven content on Twitter.16 We propose the Five A’s of MBT (Authenticity is key, Amplify other voices, Accelerate your work, Avoid arguments, Always be professional) to provide a general guide to ensuring that your tweets honor your mission (Figure). While each factor is important, we consider authenticity the most important as it guides consistency of the message, addresses your mission, and invites discussion. In this manner, even when physicians tweet about lived experiences or scientific data that may make some individuals uncomfortable, authenticity can still lead to meaningful engagement.17

There is synergy between amplifying other voices and accelerating your own work, as both provide an opportunity to highlight your specific advocacy interest. In the earlier example, the physician advocating for health justice may create a thread highlighting inequities in COVID-19 vaccination, including their own data and that of other health justice scholars, and in doing so, provide an invaluable repository of references or speakers for a future project.

We caution that not everyone will agree with your mission, so avoiding arguments and remaining professional in these interactions is paramount. Furthermore, it is also possible that a physician’s mission and opinions may not align with those of their employer, so it is important for social media users to review and clarify their employer’s social media policies to avoid violations and related repercussions. Physicians should tweet as if they were speaking into a microphone on the record, and authenticity should ground them into projecting the same personality online as they would offline.

CONCLUSION

We believe that, by the very nature of their chosen careers, physicians should step into the tension of advocacy. We acknowledge that physicians who are otherwise vocal advocates in other areas of life may be reluctant to engage on social media. However, if the measure of “success” on Twitter is meaningful interaction, sharing knowledge, and amplifying other voices according to a specific personal mission, MBT can be a useful framework. This is a call to action for hesitant physicians to take a leap and explore this platform, and for those already using social media to reevaluate their use and reflect on their mission. Physicians have been gifted a megaphone that can be used to combat misinformation, advocate for patients and the healthcare community, and advance needed discussions to benefit those in society who cannot speak for themselves. We advocate for physicians to look beyond the moment of a tweet and consider how your voice can contribute to a movement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for her contribution to early concept development for this manuscript and the JHM editorial staff for their productive feedback and editorial comments.

1. Riddick FA Jr. The code of medical ethics of the American Medical Association. Ochsner J. 2003;5(2):6-10. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

2. Vraga EK, Bode L. Addressing COVID-19 misinformation on social media preemptively and responsively. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):396-403. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

3. Campbell L, Evans Y, Pumper M, Moreno MA. Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y

4. Wetsman N. How Twitter is changing medical research. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):11-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0697-7

5. Shapiro M. Episode 107: Vinny Arora & Charlie Wray on Social Media & CVs. Explore The Space Podcast. https://www.explorethespaceshow.com/podcasting/vinny-arora-charlie-wray-on-cvs-social-media/

6. Varghese T. i4 (i to the 4th) is a strategy for #SoMe. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/TomVargheseJr/status/1027181443712081920?s=20

7. Dobson S, Voyer S, Regehr G. Perspective: agency and activism: rethinking health advocacy in the medical profession. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182621c25

8. #GetMePPE. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/hashtag/getmeppe?f=live

9. Ouyang H. At the front lines of coronavirus, turning to social media. The New York Times. March 18, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-facebook-twitter-social-media-covid.html

10. Blackstock U. Combining social media advocacy with health policy advocacy. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/uche_blackstock/status/1270413367761666048?s=20

11. Meeks LM, Liao P, Kim N. Using Twitter to promote awareness of disabilities in medicine. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):525-526. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13836

12. Nolen L. To all the little brown girls out there “you can’t be what you can’t see but I hope you see me now and that you see yourself in me.” Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/LashNolen/status/1160901502266777600?s=20.

13. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, Gottlieb M, Woitowich NC, Arora VM. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7235

14. Marcelin JR. Personal mission statement. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.unmc.edu/intmed/residencies-fellowships/residency/diverse-taskforce/index.html.

15. Li S-TT, Frohna JG, Bostwick SB. Using your personal mission statement to INSPIRE and achieve success. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):107-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.010

16. Alton L. 7 tips for creating engaging content every day. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://business.twitter.com/en/blog/7-tips-creating-engaging-content-every-day.html

17. Boyd R. Is everyone reading this??! Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/RheaBoydMD/status/1273006362679578625?s=20

“We, the members of the world community of physicians, solemnly commit ourselves to . . . advocate for social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”

— American Medical Association Oath of Professional Responsibility. 1

As individuals and groups spread misinformation on social media platforms, there is a greater need for physician health advocacy.2 We have learned through the COVID-19 pandemic that rapidly evolving information requires public-facing health experts to address misinformation and explain why healthcare providers and experts make certain recommendations.2 Physicians recognize the potential for benefit from crowdsourcing education, positive publicity, and increasing their reach to a larger platform.3

However, despite social media’s need for such expertise and these recognized benefits, many physicians are hesitant to engage on social media, citing lack of time, interest, or the proper skill set to use it effectively.3 Additional barriers may include uncertainty about employer policies, fear of saying something inaccurate or unprofessional, or inadvertently breaching patient privacy.3 While these are valid concerns, a strategic approach to curating a social media presence focuses less on the moments created by provocative tweets and more on the movement the author wishes to amplify. Here, we propose a framework for effective physician advocacy using a strategy we term Mission-Based Tweeting (MBT).

MISSION-BASED TWEETING

Physicians can use Twitter to engage large audiences.4 MBT focuses an individual’s central message by providing a framework upon which to build such engagement.5 The conceptual framework for a meaningful social media strategy through MBT is anchored on the principle that the impact of our Twitter content is more valuable than the number of followers.6 Using this framework, users begin by creating and defining their identity while engaging in meaningful online interactions. Over time, these interactions will lead to generating influence related to their established identity, which can ultimately impact the social micro-society.6 While an individual’s social media impact can be determined and reinforced through MBT, it remains important to know that MBT is not exemplified in one specific tweet, but rather in the body of work shared by an individual that continuously reinforces the mission.

TWEETING FOR THE MOMENT VS FOR THE MOVEMENT: USING MBT FOR ADVOCACY

Advocacy typically involves using one’s voice to publicly support a specific interest. With that in mind, health advocacy can be divided into two categories: (1) agency, which involves advancing the health of individual patients within a system, and (2) activism, which acts to advance the health of communities or populations or change the structure of the healthcare system.7 While many physicians accept agency as part of their day-to-day job, activism is often more difficult. For example, physicians hoping to engage in health advocacy may be unable to travel to their state or federal legislature buildings, or their employers may restrict their ability to interact with elected officials. The emergence of social media and digital technology has lowered these barriers and created more accessible opportunities for physicians to engage in advocacy efforts.

Social media can provide an opportunity for clinicians to engage with other healthcare professionals, creating movements that have far-reaching effects across the healthcare spectrum. These movements, often driven by common hashtags, have expanded greatly beyond their originators’ intent, thus demonstrating the power of social media for healthcare activism (Table).4 Physician advocacy can provide accurate information about medical conditions and treatments, dispel myths that may affect patient care, and draw attention to conditions that impact their ability to provide that care. For instance, physicians and medical students recently used Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic to focus on the real consequences of lack of access to personal protective equipment during the pandemic (Table).8,9 In the past year, physicians have used Twitter to highlight how structural racism perpetuates racial disparities in COVID-19 and to call for action against police brutality and the killing of unarmed Black citizens. Such activism has led to media appearances and even congressional testimony—which has, in turn, provided even larger audiences for clinicians’ advocacy efforts.10 Physicians can also use MBT to advocate for the medical profession. Strategic, mission-based, social media campaigns have focused on including women; Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); doctors with disabilities; and LGBTQ+ physicians in the narrative of what a doctor looks like (Table).11,12

When physicians consider their personal mission statement as it applies to their social media presence, it allows them to connect to something bigger than themselves, while helping guide them away from engagements that do not align with their personal or professional values. In this manner, MBT harnesses an individual’s authenticity and helps build their personal branding, which may ultimately result in more opportunities to advance their mission. In our experience, the constant delivery of mission-based content can even accelerate one’s professional work, help amplify others’ successes and voices, and ultimately lead to more meaningful engagement and activism.

However, it is important to note that there are potential downsides to engaging on social media, particularly for women and BIPOC users. For example, in a recent online survey, almost a quarter of physicians who responded reported personal attacks on social media, with one in six female physicians reporting sexual harassment.13 This risk may increase as an individual’s visibility and reach increase.

DEVELOP YOUR MISSION STATEMENT