User login

Communication has always played a central role in facilitating technological advances and social progress. The printing press, mail, telegraph, radio, television, electronic mail, and social media have all allowed for the exchange of ideas that led to progress, and have done so with increasing speed. But some people are beginning to question whether we are experiencing diminishing returns from making such communication easier, faster, and more widespread. Disinformation, conspiracies, inappropriate messages, and personal attacks are just as easy to communicate as truth, good ideas, and empathy. In many cases, truth and falsehood are nearly indistinguishable. Raw, nasty emotions contained in personal attacks are often provocative, thus generating even more engagement, which many people view as the purpose of social media. In this context, it is more important than ever for trusted voices, such as those of scientists and physicians, to play a role in the public sphere.

In this essay, we offer our personal recommendations on how healthcare professionals, who in our view have outsized authority and responsibility on healthcare topics, might improve communication on social media. We focus particularly on Twitter given its prominent role in the public exchange of ideas and its recognized benefits (and challenges) for scientific communication.1 We make these recommendations with some trepidation because we are sure readers will be able to find times when we have not followed our own advice. And we are sure many will disagree or feel that our advice raises the bar too high. We divide our recommendations into lists of Do’s and Don’ts. Let’s start with the Do’s.

DO

DO separate facts from inferences, ideally labeling them as such. For example, you can report that public health has found five cases of the delta variant in people in a specific nursing home as a fact. You might then infer that the variant is widespread in that facility, and that community spread in the region is likely. Stating the source of your facts helps the reader evaluate their reliability and precision.

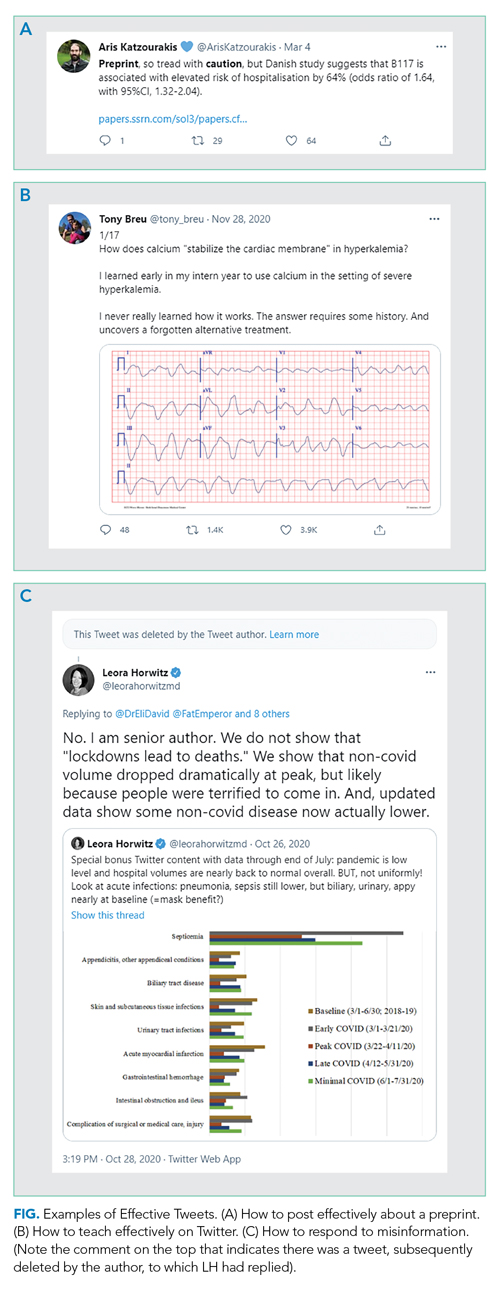

DO state when you are quoting preliminary evidence. If posting a preprint, press release, or other non-peer-reviewed paper (even if it is your own!), make its preliminary status clear to the reader (Figure, part A).

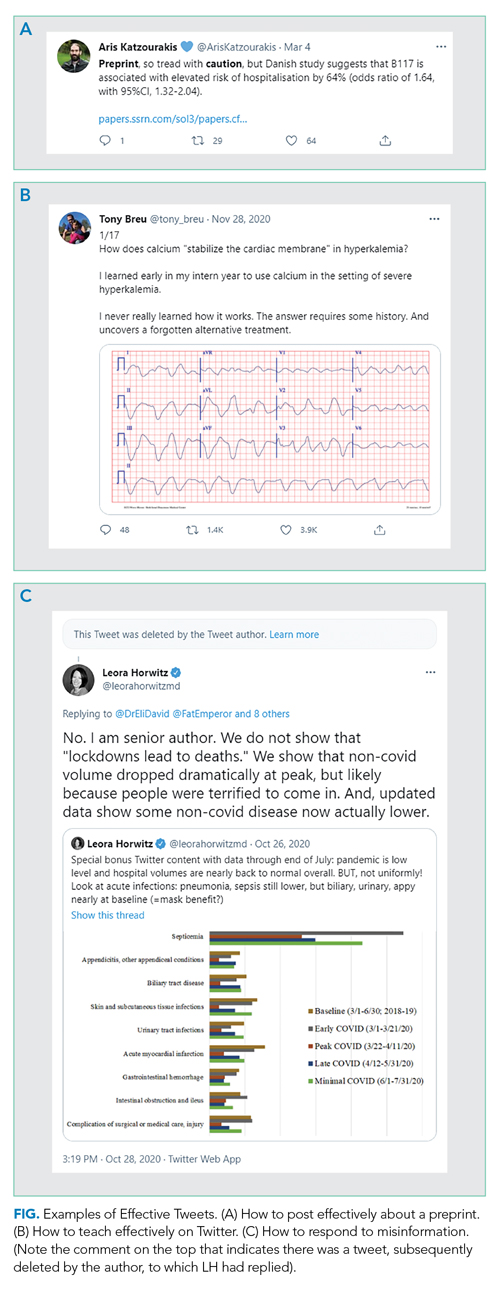

DO read the full article before posting. If you are posting an article, make sure you understand the whole context of any results you are highlighting. Avoid exaggerating, fear-mongering, or selectively picking facts or results to bolster your opinion.DO seek to add value to the public discourse. Rather than simply retweeting popular posts, consider taking the time to collate evidence (including contrary evidence) into a thread if seeking to prove a point or to teach, especially when it relates to something in your field. You likely are more knowledgeable about topics in your field than 99% of readers; use Twitter to spread your expertise. Clinical “tweetorials,” such as those popularized by @tony_breu, can be very effective teaching tools (Figure, part B).

DO make recommendations as specific as possible. If your goal is to improve adherence to evidence-based medicine or support disadvantaged people, be explicit about how you would achieve these goals. Tell readers exactly what you have in mind so that individuals and leaders can operationalize the recommendations. Use threads to expand on your advice and its rationale.

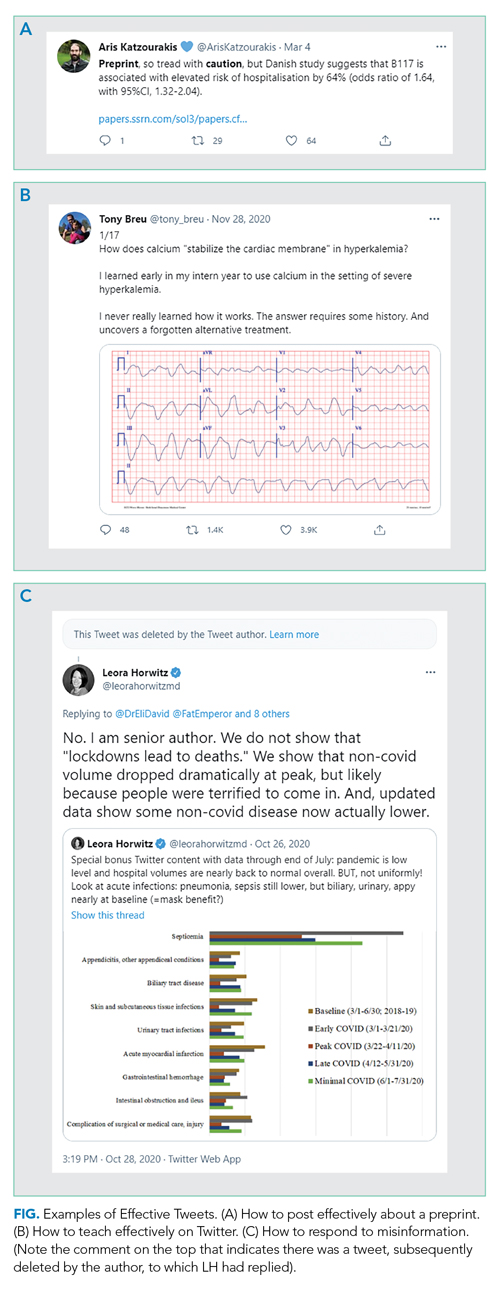

DO consider engaging with misinformation. We suggest doing so if the misinformation is posted by someone prominent who is likely to have broad reach, but only once per post and in a factual manner. You are unlikely to convince persons who post disinformation that they are wrong; extended arguments are unhelpful. Your role here is simply to inform readers of the post, who may be more open to reason. Occasionally, you may even convince the initial poster, as seen in Figure, part C, to delete certain misinformation. But don’t count on it.

DO consider your obligation to the general public. It is fine to engage explicitly with the medical community (ie, through tweetchats),2 but also consider that your comments will be accessible to everyone. Now more than ever the public is looking to healthcare professionals for clarity, reassurance, and evidence about medical matters.

DO acknowledge when you were wrong. Update your opinions as facts change or when you realize you made a mistake. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought home the rapidity with which we can gain scientific knowledge. Many of the things we thought were right early on—and posted about on Twitter—we now know to be wrong. Be forthright about this, while making it clear that the fact that we know more now doesn’t mean no information can be trusted. (A corollary: Don’t overstate what we know to be true at any time, so that it does not feel as much of a surprise if we later learn more and need to revise an opinion or a statement.)

DO be kind. This is perhaps the most important thing. We are all experiencing stress as physicians, parents, children, and colleagues. Spend your time focusing on people’s actions rather than impugning their motives or intelligence. Most of the time you don’t really know what their motives are. We recognize that kindness may not generate the same amount of engagement as sarcasm, but at least take time to consider whether you want to be seen as mean-spirited forever.

DO pause before sending. Twitter creates a false perception of the need for speed (and doesn’t really lend itself to revising drafts). But in reality, there is no rush. The torrent of Twitter posts means that people typically only see what has been posted around the time they log in; an early post is not necessarily more likely to be noticed. So, take your time and avoid falling into a trap of writing something you will regret, or, in extreme cases, that will get you fired or otherwise ruin your career. There is no rush to be first; Twitter will still be there tomorrow.

DON’T

For some time, mentors have warned physicians (and others whose careers depend on their reputation) to be careful in their use of social media. Electronic dissemination of inappropriate words or images can come back to haunt people—sometimes immediately, sometimes many years later.3 Physicians are also at risk of falling into some pitfalls specific to the profession. That said, here are some Don’ts to avoid or be cautious about.

DON’T reveal information about patients in a recognizable fashion. Journals ask for written consent from patients when authors submit a manuscript about individual cases so readers can be sure consent has been obtained. The same standard should apply to social media; if not, you are clearly violating a professional standard. Yet, on Twitter, people may assume you have not obtained consent, conveying a false sense of invasion of privacy and undermining confidence in the profession. The safest thing to do is not tell stories about patients, or to completely disguise the story so even the patients can’t recognize themselves. If you do choose to post about a patient, obtain written permission that you save, and clearly indicate that you have that permission in the Tweet.

DON’T claim to have expertise in areas where you have little training or education. For example, just because you are an expert in critical care and have seen the ravages of COVID-19 on your patients doesn’t mean you are an expert in how to stop a pandemic, though your observations may be helpful to those who are. This does not mean you shouldn’t speak out on important moral issues like climate change, nuclear war, or injustices, which clearly reflect personal opinion and values. Rather, be cautious about commenting authoritatively on areas in which the lay reader might mistakenly think you have specific expertise.

DON’T make yourself the hero of every story. Implicitly seeking praise for doing your job (Look at me, I’m working on Christmas!) may breed resentment and undercut professionalism. Rather, state what it is about your job that works well and what doesn’t (for example, teaching tips, wellness advice, and organizational strategies) in a way that helps others emulate your successes.

DON’T let emotions get the better of you. This past year has been full of outrageous and appalling events and behavior. We do not suggest that you ignore these. Rather, make sure that if you are blaming an individual for something that it really was their fault, because they had control of the factors that led to the disastrous outcome. Consider focusing on systemic and structural explanations for unacceptable phenomena to minimize defensiveness and maximize the potential for identifying solutions. And yes, sometimes you just have to let it rip, but be selective—maybe show your post to someone else and sleep on it before you send it.

CONCLUSION

We hope that you will find these suggestions helpful in both creating and reading social media posts on important topics. We recognize that some people like the spontaneity of the social media platform and will thus find our suggestions stunting. But at least everyone ought to consider what they are trying to achieve when they make public statements. The exchange of ideas has always been a key ingredient in creating progress. Let’s optimize the usefulness of those exchanges for that purpose, and to promote knowledge and science in a way that helps us all live healthier and happier lives.

1. Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37(5):411-416. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.993371

2. Admon AJ, Kaul V, Cribbs SK, Guzman E, Jimenez O, Richards JB. Twelve tips for developing and implementing a medical education Twitter chat. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):500-506. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1598553

3. Langenfeld SJ, Batra R. How can social media get us in trouble? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(4):264-269. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604255

Communication has always played a central role in facilitating technological advances and social progress. The printing press, mail, telegraph, radio, television, electronic mail, and social media have all allowed for the exchange of ideas that led to progress, and have done so with increasing speed. But some people are beginning to question whether we are experiencing diminishing returns from making such communication easier, faster, and more widespread. Disinformation, conspiracies, inappropriate messages, and personal attacks are just as easy to communicate as truth, good ideas, and empathy. In many cases, truth and falsehood are nearly indistinguishable. Raw, nasty emotions contained in personal attacks are often provocative, thus generating even more engagement, which many people view as the purpose of social media. In this context, it is more important than ever for trusted voices, such as those of scientists and physicians, to play a role in the public sphere.

In this essay, we offer our personal recommendations on how healthcare professionals, who in our view have outsized authority and responsibility on healthcare topics, might improve communication on social media. We focus particularly on Twitter given its prominent role in the public exchange of ideas and its recognized benefits (and challenges) for scientific communication.1 We make these recommendations with some trepidation because we are sure readers will be able to find times when we have not followed our own advice. And we are sure many will disagree or feel that our advice raises the bar too high. We divide our recommendations into lists of Do’s and Don’ts. Let’s start with the Do’s.

DO

DO separate facts from inferences, ideally labeling them as such. For example, you can report that public health has found five cases of the delta variant in people in a specific nursing home as a fact. You might then infer that the variant is widespread in that facility, and that community spread in the region is likely. Stating the source of your facts helps the reader evaluate their reliability and precision.

DO state when you are quoting preliminary evidence. If posting a preprint, press release, or other non-peer-reviewed paper (even if it is your own!), make its preliminary status clear to the reader (Figure, part A).

DO read the full article before posting. If you are posting an article, make sure you understand the whole context of any results you are highlighting. Avoid exaggerating, fear-mongering, or selectively picking facts or results to bolster your opinion.DO seek to add value to the public discourse. Rather than simply retweeting popular posts, consider taking the time to collate evidence (including contrary evidence) into a thread if seeking to prove a point or to teach, especially when it relates to something in your field. You likely are more knowledgeable about topics in your field than 99% of readers; use Twitter to spread your expertise. Clinical “tweetorials,” such as those popularized by @tony_breu, can be very effective teaching tools (Figure, part B).

DO make recommendations as specific as possible. If your goal is to improve adherence to evidence-based medicine or support disadvantaged people, be explicit about how you would achieve these goals. Tell readers exactly what you have in mind so that individuals and leaders can operationalize the recommendations. Use threads to expand on your advice and its rationale.

DO consider engaging with misinformation. We suggest doing so if the misinformation is posted by someone prominent who is likely to have broad reach, but only once per post and in a factual manner. You are unlikely to convince persons who post disinformation that they are wrong; extended arguments are unhelpful. Your role here is simply to inform readers of the post, who may be more open to reason. Occasionally, you may even convince the initial poster, as seen in Figure, part C, to delete certain misinformation. But don’t count on it.

DO consider your obligation to the general public. It is fine to engage explicitly with the medical community (ie, through tweetchats),2 but also consider that your comments will be accessible to everyone. Now more than ever the public is looking to healthcare professionals for clarity, reassurance, and evidence about medical matters.

DO acknowledge when you were wrong. Update your opinions as facts change or when you realize you made a mistake. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought home the rapidity with which we can gain scientific knowledge. Many of the things we thought were right early on—and posted about on Twitter—we now know to be wrong. Be forthright about this, while making it clear that the fact that we know more now doesn’t mean no information can be trusted. (A corollary: Don’t overstate what we know to be true at any time, so that it does not feel as much of a surprise if we later learn more and need to revise an opinion or a statement.)

DO be kind. This is perhaps the most important thing. We are all experiencing stress as physicians, parents, children, and colleagues. Spend your time focusing on people’s actions rather than impugning their motives or intelligence. Most of the time you don’t really know what their motives are. We recognize that kindness may not generate the same amount of engagement as sarcasm, but at least take time to consider whether you want to be seen as mean-spirited forever.

DO pause before sending. Twitter creates a false perception of the need for speed (and doesn’t really lend itself to revising drafts). But in reality, there is no rush. The torrent of Twitter posts means that people typically only see what has been posted around the time they log in; an early post is not necessarily more likely to be noticed. So, take your time and avoid falling into a trap of writing something you will regret, or, in extreme cases, that will get you fired or otherwise ruin your career. There is no rush to be first; Twitter will still be there tomorrow.

DON’T

For some time, mentors have warned physicians (and others whose careers depend on their reputation) to be careful in their use of social media. Electronic dissemination of inappropriate words or images can come back to haunt people—sometimes immediately, sometimes many years later.3 Physicians are also at risk of falling into some pitfalls specific to the profession. That said, here are some Don’ts to avoid or be cautious about.

DON’T reveal information about patients in a recognizable fashion. Journals ask for written consent from patients when authors submit a manuscript about individual cases so readers can be sure consent has been obtained. The same standard should apply to social media; if not, you are clearly violating a professional standard. Yet, on Twitter, people may assume you have not obtained consent, conveying a false sense of invasion of privacy and undermining confidence in the profession. The safest thing to do is not tell stories about patients, or to completely disguise the story so even the patients can’t recognize themselves. If you do choose to post about a patient, obtain written permission that you save, and clearly indicate that you have that permission in the Tweet.

DON’T claim to have expertise in areas where you have little training or education. For example, just because you are an expert in critical care and have seen the ravages of COVID-19 on your patients doesn’t mean you are an expert in how to stop a pandemic, though your observations may be helpful to those who are. This does not mean you shouldn’t speak out on important moral issues like climate change, nuclear war, or injustices, which clearly reflect personal opinion and values. Rather, be cautious about commenting authoritatively on areas in which the lay reader might mistakenly think you have specific expertise.

DON’T make yourself the hero of every story. Implicitly seeking praise for doing your job (Look at me, I’m working on Christmas!) may breed resentment and undercut professionalism. Rather, state what it is about your job that works well and what doesn’t (for example, teaching tips, wellness advice, and organizational strategies) in a way that helps others emulate your successes.

DON’T let emotions get the better of you. This past year has been full of outrageous and appalling events and behavior. We do not suggest that you ignore these. Rather, make sure that if you are blaming an individual for something that it really was their fault, because they had control of the factors that led to the disastrous outcome. Consider focusing on systemic and structural explanations for unacceptable phenomena to minimize defensiveness and maximize the potential for identifying solutions. And yes, sometimes you just have to let it rip, but be selective—maybe show your post to someone else and sleep on it before you send it.

CONCLUSION

We hope that you will find these suggestions helpful in both creating and reading social media posts on important topics. We recognize that some people like the spontaneity of the social media platform and will thus find our suggestions stunting. But at least everyone ought to consider what they are trying to achieve when they make public statements. The exchange of ideas has always been a key ingredient in creating progress. Let’s optimize the usefulness of those exchanges for that purpose, and to promote knowledge and science in a way that helps us all live healthier and happier lives.

Communication has always played a central role in facilitating technological advances and social progress. The printing press, mail, telegraph, radio, television, electronic mail, and social media have all allowed for the exchange of ideas that led to progress, and have done so with increasing speed. But some people are beginning to question whether we are experiencing diminishing returns from making such communication easier, faster, and more widespread. Disinformation, conspiracies, inappropriate messages, and personal attacks are just as easy to communicate as truth, good ideas, and empathy. In many cases, truth and falsehood are nearly indistinguishable. Raw, nasty emotions contained in personal attacks are often provocative, thus generating even more engagement, which many people view as the purpose of social media. In this context, it is more important than ever for trusted voices, such as those of scientists and physicians, to play a role in the public sphere.

In this essay, we offer our personal recommendations on how healthcare professionals, who in our view have outsized authority and responsibility on healthcare topics, might improve communication on social media. We focus particularly on Twitter given its prominent role in the public exchange of ideas and its recognized benefits (and challenges) for scientific communication.1 We make these recommendations with some trepidation because we are sure readers will be able to find times when we have not followed our own advice. And we are sure many will disagree or feel that our advice raises the bar too high. We divide our recommendations into lists of Do’s and Don’ts. Let’s start with the Do’s.

DO

DO separate facts from inferences, ideally labeling them as such. For example, you can report that public health has found five cases of the delta variant in people in a specific nursing home as a fact. You might then infer that the variant is widespread in that facility, and that community spread in the region is likely. Stating the source of your facts helps the reader evaluate their reliability and precision.

DO state when you are quoting preliminary evidence. If posting a preprint, press release, or other non-peer-reviewed paper (even if it is your own!), make its preliminary status clear to the reader (Figure, part A).

DO read the full article before posting. If you are posting an article, make sure you understand the whole context of any results you are highlighting. Avoid exaggerating, fear-mongering, or selectively picking facts or results to bolster your opinion.DO seek to add value to the public discourse. Rather than simply retweeting popular posts, consider taking the time to collate evidence (including contrary evidence) into a thread if seeking to prove a point or to teach, especially when it relates to something in your field. You likely are more knowledgeable about topics in your field than 99% of readers; use Twitter to spread your expertise. Clinical “tweetorials,” such as those popularized by @tony_breu, can be very effective teaching tools (Figure, part B).

DO make recommendations as specific as possible. If your goal is to improve adherence to evidence-based medicine or support disadvantaged people, be explicit about how you would achieve these goals. Tell readers exactly what you have in mind so that individuals and leaders can operationalize the recommendations. Use threads to expand on your advice and its rationale.

DO consider engaging with misinformation. We suggest doing so if the misinformation is posted by someone prominent who is likely to have broad reach, but only once per post and in a factual manner. You are unlikely to convince persons who post disinformation that they are wrong; extended arguments are unhelpful. Your role here is simply to inform readers of the post, who may be more open to reason. Occasionally, you may even convince the initial poster, as seen in Figure, part C, to delete certain misinformation. But don’t count on it.

DO consider your obligation to the general public. It is fine to engage explicitly with the medical community (ie, through tweetchats),2 but also consider that your comments will be accessible to everyone. Now more than ever the public is looking to healthcare professionals for clarity, reassurance, and evidence about medical matters.

DO acknowledge when you were wrong. Update your opinions as facts change or when you realize you made a mistake. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought home the rapidity with which we can gain scientific knowledge. Many of the things we thought were right early on—and posted about on Twitter—we now know to be wrong. Be forthright about this, while making it clear that the fact that we know more now doesn’t mean no information can be trusted. (A corollary: Don’t overstate what we know to be true at any time, so that it does not feel as much of a surprise if we later learn more and need to revise an opinion or a statement.)

DO be kind. This is perhaps the most important thing. We are all experiencing stress as physicians, parents, children, and colleagues. Spend your time focusing on people’s actions rather than impugning their motives or intelligence. Most of the time you don’t really know what their motives are. We recognize that kindness may not generate the same amount of engagement as sarcasm, but at least take time to consider whether you want to be seen as mean-spirited forever.

DO pause before sending. Twitter creates a false perception of the need for speed (and doesn’t really lend itself to revising drafts). But in reality, there is no rush. The torrent of Twitter posts means that people typically only see what has been posted around the time they log in; an early post is not necessarily more likely to be noticed. So, take your time and avoid falling into a trap of writing something you will regret, or, in extreme cases, that will get you fired or otherwise ruin your career. There is no rush to be first; Twitter will still be there tomorrow.

DON’T

For some time, mentors have warned physicians (and others whose careers depend on their reputation) to be careful in their use of social media. Electronic dissemination of inappropriate words or images can come back to haunt people—sometimes immediately, sometimes many years later.3 Physicians are also at risk of falling into some pitfalls specific to the profession. That said, here are some Don’ts to avoid or be cautious about.

DON’T reveal information about patients in a recognizable fashion. Journals ask for written consent from patients when authors submit a manuscript about individual cases so readers can be sure consent has been obtained. The same standard should apply to social media; if not, you are clearly violating a professional standard. Yet, on Twitter, people may assume you have not obtained consent, conveying a false sense of invasion of privacy and undermining confidence in the profession. The safest thing to do is not tell stories about patients, or to completely disguise the story so even the patients can’t recognize themselves. If you do choose to post about a patient, obtain written permission that you save, and clearly indicate that you have that permission in the Tweet.

DON’T claim to have expertise in areas where you have little training or education. For example, just because you are an expert in critical care and have seen the ravages of COVID-19 on your patients doesn’t mean you are an expert in how to stop a pandemic, though your observations may be helpful to those who are. This does not mean you shouldn’t speak out on important moral issues like climate change, nuclear war, or injustices, which clearly reflect personal opinion and values. Rather, be cautious about commenting authoritatively on areas in which the lay reader might mistakenly think you have specific expertise.

DON’T make yourself the hero of every story. Implicitly seeking praise for doing your job (Look at me, I’m working on Christmas!) may breed resentment and undercut professionalism. Rather, state what it is about your job that works well and what doesn’t (for example, teaching tips, wellness advice, and organizational strategies) in a way that helps others emulate your successes.

DON’T let emotions get the better of you. This past year has been full of outrageous and appalling events and behavior. We do not suggest that you ignore these. Rather, make sure that if you are blaming an individual for something that it really was their fault, because they had control of the factors that led to the disastrous outcome. Consider focusing on systemic and structural explanations for unacceptable phenomena to minimize defensiveness and maximize the potential for identifying solutions. And yes, sometimes you just have to let it rip, but be selective—maybe show your post to someone else and sleep on it before you send it.

CONCLUSION

We hope that you will find these suggestions helpful in both creating and reading social media posts on important topics. We recognize that some people like the spontaneity of the social media platform and will thus find our suggestions stunting. But at least everyone ought to consider what they are trying to achieve when they make public statements. The exchange of ideas has always been a key ingredient in creating progress. Let’s optimize the usefulness of those exchanges for that purpose, and to promote knowledge and science in a way that helps us all live healthier and happier lives.

1. Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37(5):411-416. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.993371

2. Admon AJ, Kaul V, Cribbs SK, Guzman E, Jimenez O, Richards JB. Twelve tips for developing and implementing a medical education Twitter chat. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):500-506. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1598553

3. Langenfeld SJ, Batra R. How can social media get us in trouble? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(4):264-269. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604255

1. Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37(5):411-416. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.993371

2. Admon AJ, Kaul V, Cribbs SK, Guzman E, Jimenez O, Richards JB. Twelve tips for developing and implementing a medical education Twitter chat. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):500-506. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1598553

3. Langenfeld SJ, Batra R. How can social media get us in trouble? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(4):264-269. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604255

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine