User login

Principles and Practice of Gossiping About Colleagues in Medicine

CLINICAL SCENARIO PROLOGUE

You are signing over to a colleague on the COVID-19 inpatient hospital ward. You are stressed after having failed to reach the chief medical resident who did not respond despite repeated texts. You think about mentioning this apparent professional lapse to your colleague. You pause, however, because you are uncertain about the appropriate norm, hesitant around finding the right words, and unsure about a mutual feeling of camaraderie.

OVERVIEW

Lay and scientific perspectives about gossip diverge widely. Lay definitions of gossip generally include malicious, salacious, immoral, trivial, or unfair comments that attack someone else’s reputation. Scientific definitions of gossip, in contrast, also include neutral or positive social information intended to align group dynamics.1 The common feature of both is that the named individual is not present to hear about themselves.2 A further commonality is that gossip involves informal assessments loaded with subjective judgments, unlike professional comments about patients from clinicians providing care. In contrast to stereotype remarks, gossip focuses on a specific person and not a group.

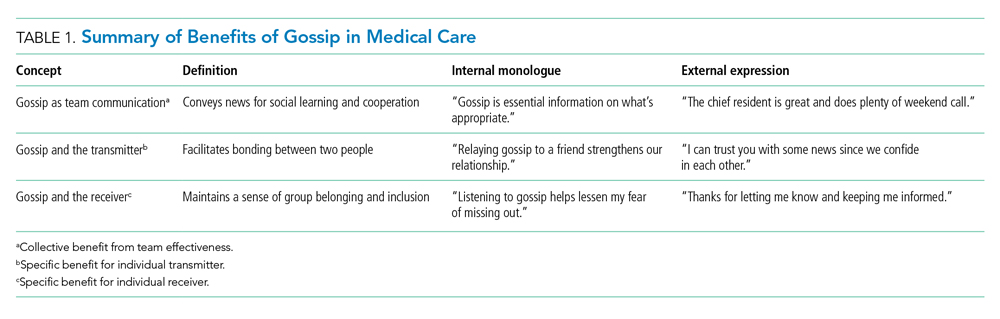

Gossip is widespread. A recent study in nonhospital settings suggests nearly all adults engage in gossip during normal interactions, averaging 52 minutes on a typical day.3 Most gossip is neutral (74%) rather than negative or positive. The content usually (92%) concerns relationships, and the typical person identified (82%) is an acquaintance. Some of the potential benefits include conveying information for social learning, defining what is socially acceptable, or promoting personal connections. Men and women gossip to nearly the same degree.4 Indeed, evolutionary theory suggests gossip is not deviant behavior and arises even in small hunter-gatherer communities.5Social psychology science provides some insights on fundamental principles of gossip that may be relevant to clinicians in medicine.6 In this article, we review three important findings from social psychology science relevant to team cooperation, the specific transmitter, and the individual receiver (Table 1). Clinicians working in groups may benefit from recognizing the prosocial function of healthy gossip and avoiding the antisocial adverse effects of harmful gossip.7 At a time when work-related conversations have radically shifted online,8 hospitalists need to be aware of positives and pitfalls of gossip to help provide effective medical care and avoid adverse events.

GOSSIP AS TEAM COMMUNICATION

Large team endeavors often require social signals to coordinate people.9 Gossip helps groups establish reputations, monitor their members, deter antisocial behavior, and protect newcomers from exploitation.10 Sharing social information can also indirectly promote cooperation because individuals place a high value on their own reputations and want to avoid embarrassment.11,12 The absence of gossip, in contrast, may lead individuals to be oblivious to team expectations and fail to do their fair share. A lack of gossip, in particular, may add to inefficiencies during the COVID-19 pandemic since exchanging gossip seems to feel awkward over email or other digital channels (albeit a chat function for side conversations in virtual meetings is a partial substitute).13,14

A paradigm for testing the positive effects of gossip involves a trust game where participants consider making small contributions for later rewards in recurrent rounds of cooperation.15-17 In one online study of volunteers, for example, individuals contributed to a group account and gained rewards equal to a doubling of total contributions shared over everyone equally (even those contributing nothing).18 Half the experiments allowed participants to send notes about other participants, whereas the other experiments allowed no such “gossip.” As predicted, gossip increased the proportion contributed (40% vs 32%, P = .020) and average total reward (64 vs 56, P = .002). In this and other studies of healthy volunteers, gossip builds trust and increases gains for the entire group.19-22

Effective medical practice inside hospitals often involves constructive gossip for pointers on how to behave (eg, how quickly to reply to a text message from the ward pharmacist). The blend of objective facts with subjective opinion provides a compelling message otherwise lacking from institutional guidelines or directives on how not to behave (eg, how quickly to complete an annual report with an arbitrary deadline). Gossip is the antithesis of a cursory interaction between strangers and is also less awkward than open flattery or public ridicule that may occur when the third person is in earshot.23 Even negative social comparisons can be constructive to listeners since people want to know how to avoid bad gossip about themselves in a world with changing morality.24

GOSSIP AND THE TRANSMITTER

Gossip can provide a distinct emotional benefit for the gossiper as a form of self-expression, an exercise of justice, and a validation of one’s perspective.25 Consider, for example, witnessing an antisocial act that leads to subsequent feelings of unfairness yet having no way to communicate personal dissatisfaction. Similarly, expressing prosocial gossip may help relieve some of the annoyance after a hassle (eg, talking with a friend after encountering a new onerous hospital protocol). The sharing of gossip might also help bolster solidarity after an offense (eg, talking with a friend on how to deal with another warning from health records).26 In contrast, lost opportunities to gossip about unfairness could be exacerbating the social isolation and emotional distress of the COVID-19 pandemic.27,28

A rigorous example of the emotional benefits of expressing gossip involves undergraduates witnessing staged behavior under laboratory conditions where one actor appeared to exploit the generosity of another actor.29 By random assignment, half the participants had an opportunity to gossip, and the other half had no such opportunity. All participants reacted to the antisocial behavior by feeling frustrated (self-report survey scale of 0-100, where higher scores indicate worse frustration). Importantly, almost all chose to engage in gossip when feasible, and those who had the opportunity to gossip experienced more relief than those who had no opportunity (absolute improvement in frustration scores, 9.69 vs 0.16; P < .01). Evidentially, engaging in prosocial gossip can sometimes provide solace.

Sharing gossip might strengthen social bonds, bolster self-esteem, promote personal power, elicit reciprocal favors, or telegraph the presence of a larger network of personal connections. Gossip is cheap and efficient compared with peer-sanctioning or formal sanctioning to control behavior.30 Airing grievances through gossip may also solve some social dilemmas more easily than channeling messages through institutional reporting structures or formal performance reviews. Gossip has another advantage of raising delicate comparative judgments without the discomfort of direct confrontation (eg, defining the appropriate level of detail for a case presentation is perhaps best done by identifying those who are judged too verbose).31

GOSSIP AND THE RECEIVER

People tend to enjoy listening to gossip despite the uneven quality where some comments are more valuable than others. The receiver, therefore, faces an irregular payoff similar to random intermittent reinforcement. Ironically, random intermittent reinforcement can be particularly addictive when compared with steady rewards with predictable payoffs. This includes cases where gossip conveys good news that helps elevate, inspire, or motivate the receiver. The thirst for more gossip may partially explain why receivers keep seeking gossip despite knowing the material may be unimportant. The shortfall of enticing gossip might also be another factor adding to a feeling of loneliness that prevails widely during the COVID-19 pandemic.32,33

Classic research on reinforcement includes experiments examining operant conditioning for creating addiction.34,35 An important distinction is the contrast between random reinforcement (eg, variable reward akin to gambling on a roulette wheel) and consistent reinforcement (eg, regular pay akin to a steady salary each week). In a study of pigeons trained to peck a lever for food, for example, random reinforcement resulted in twice the response compared with consistent reinforcement (despite an equalized total amount of food received).36 Moreover, random reinforcement was hard to extinguish, and the behavior continued long after all food ended. In general, random compared with consistent reinforcement tended to cause a more intense and persistent change of behavior.

The inconsistent quality makes the prospect of new, exciting gossip seem nearly impossible to resist; indeed, gossip from any source is surprisingly tantalizing. Moreover, the validity of gossip is rarely challenged, unlike the typical norm of lively thoughtful debate that surrounds new ideas (eg, whether to prescribe a novel medication).2 Gossip, of course, can also lead to a positive thrill where, for example, a recipient subsequently feels emboldened with passionate enthusiasm to relay the point to others. This means that spreading inaccurate characterizations may be particularly destructive for a listener who is gullible or easily provoked.37 Conversely, gossip can also lead to anxiety about future uncertainties.38

DISCUSSION

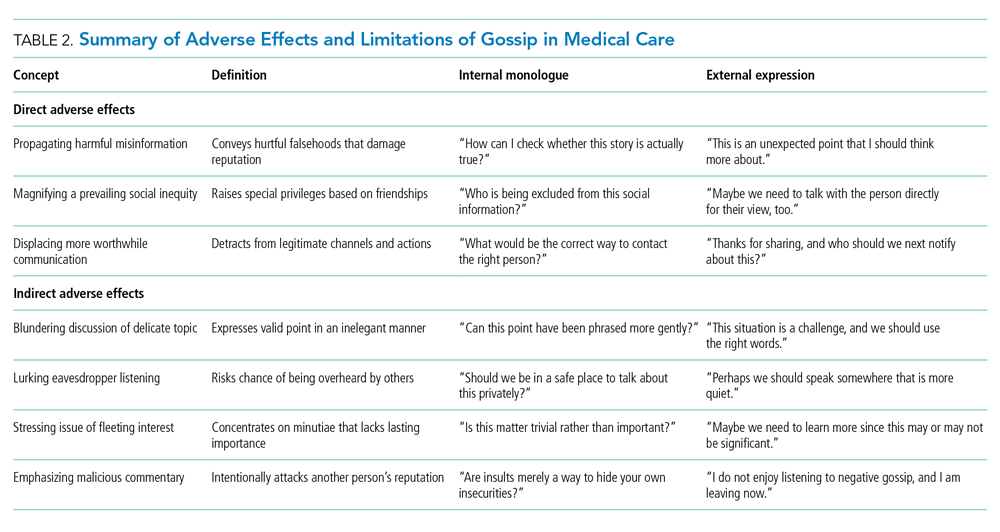

This perspective summarizes positive and negative features of gossip drawn from social psychology science on a normally hidden activity. The main benefits in medical care are to support team communication, the specific transmitter, and the individual receiver. Some specific gains are to enhance team cooperation, deter exploitation, signal trust, and convey codes of conduct. Sharing gossip might also promote honest dialogue, foster friendships, facilitate reciprocity, and curtail excessive use of force by a dominant individual. Listening to gossip possibly also reduces loneliness, affirms an innate desire for inclusion, and provides a way to share insights. Of course, gossip has downsides from direct or indirect adverse effects that merit attention and mitigation (Table 2).

A large direct downside of gossip is in propagating damaging misinformation that harms individuals.24 Toxic gossip can wreck relationships, hurt feelings, violate privacy, and manipulate others. Malicious gossip may become further accentuated because of groupthink, polarization, or selfish biases.39 Presumably, these downsides of gossip are sufficiently infrequent because regular people spend substantial time, attention, and effort engaging in gossip.3 In society, healthy gossip that propagates positive information goes by synonyms having a less negative connotation, including socializing, networking, chatting, schmoozing, friendly banter, small talk, and scuttlebutt. The net benefits must be real since one person is often both a transmitter and a receiver of gossip over time.

Another large direct limitation of gossip is that it can magnify social inequities by allowing some people but not others to access hidden information. In essence, receiving gossip is a privilege that is not universally available within a community and depends on social capital.40 Gossip helps strengthen personal bonds, so marginalized individuals can become further disempowered by not receiving gossip. Social exclusion is painful when different individuals realize they are left out of gossip circles. In summary, gossip can provide an unfair advantage because it allows only some people to learn what is going on behind their backs (eg, different hospitalists within the same institution may have differing circles of friendships for different professional advantages).

Gossip is a way to communicate priorities and regulate behavior. Without interpersonal comparisons, clinicians might find themselves adrift in a complex, difficult, and mysterious medical world. Listening to intelligent gossip can also be an effective way to learn lessons that are otherwise difficult to grasp (eg, an impolite comment may be more easily recognized in someone else than in yourself).41 Perhaps this explains why hospital executives gossip about physicians and vice versa.42 Healthy gossip tends to be positive or neutral (not malicious or negative), propagates accurate information (not hurtful falsehoods), and corrects social inequities (not worsening unearned privileges).43 We suggest that a careful practice of healthy gossip may help regulate trust, enhance social bonding, shape how people feel working together, and promote collective benefit.

CLINICAL SCENARIO EPILOGUE

Your colleague spontaneously comments that the chief medical resident is away because of a death in the family. In turn, you realize you were unaware of this personal nuance because the point was unmentioned in the (virtual) staff meeting last week. You thank your colleague for tactfully relaying the point. You also secretly wonder what other interpersonal details you might be missing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cindy Kao, Fizza Manzoor, Sheharyar Raza, Lee Ross, Miriam Shuchman, and William Silverstein for helpful suggestions on specific points.

1. Foster EK. Research on gossip: taxonomy, methods, and future directions. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):78-99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.78

2. Eder D, Enke JL. The structure of gossip: opportunities and constraints on collective expression among adolescents. Am Sociol Rev. 1991;56(4):494-508. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096270

3. Robbins ML, Karan A. Who gossips and how in everyday life. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(2):185-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619837000

4. Nevo O, Nevo B, Derech-Zehavi A. The development of the Tendency to Gossip Questionnaire: construct and concurrent validation for a sample of Israeli college students. Educ Psychol Meas. 1993;53(4):973-981. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053004010

5. Nishi A. Evolution and social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:132-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.015

6. Redelmeier DA, Ross LD. Practicing medicine with colleagues: pitfalls from social psychology science. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):624-626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04839-5

7. Baumeister RF, Zhang L, Vohs KD. Gossip as cultural learning. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):111-121. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.111

8. Kulkarni A. Navigating loneliness in the era of virtual care. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):307-309. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1813713

9. Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291-1298. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04131

10. Dunbar RIM. Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):100-110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100

11. Emler N. A social psychology of reputation. Eur Rev Social Psychol. 2011;1(1):171-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779108401861

12. Arendt F, Forrai M, Findl O. Dealing with negative reviews on physician-rating websites: an experimental test of how physicians can prevent reputational damage via effective response strategies. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113422

13. Seo H. Blah blah blah: the lack of small talk is breaking our brains. The Walrus. April 22, 2021. Updated April 22, 2021. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://thewalrus.ca/blah-blah-blah-the-lack-of-small-talk-is-breaking-our-brains/

14. Houchens N, Tipirneni R. Compassionate communication amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):437-439. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3472

15. Camerer CE. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton University Press; 2003.

16. Sommerfeld RD, Krambeck HJ, Semmann D, Milinski M. Gossip as an alternative for direct observation in games of indirect reciprocity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(44):17435-17440. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0704598104

17. Hendriks A. SoPHIE - Software Platform for Human Interaction Experiments. Working Paper. 2012.

18. Wu J, Balliet D, Van Lange PAM. Gossip versus punishment: the efficiency of reputation to promote and maintain cooperation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23919. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23919

19. Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. Reputation helps solve the “tragedy of the commons.” Nature. 2002;415(6870):424-426. https://doi.org/10.1038/415424a

20. Bolton GE, Katok E, Ockenfels A. Cooperation among strangers with limited information about reputation. J Publ Econ. 2005;89(8):1457-1468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.03.008

21. Seinen I, Schram A. Social status and group norms: indirect reciprocity in a repeated helping experiment. Eur Econ Rev. 2006;50(3):581-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.10.005

22. Feinberg M, Willer R, Schultz M. Gossip and ostracism promote cooperation in groups. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(3):656-664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613510184

23. Farley SD. Is gossip power? The inverse relationships between gossip, power, and likability. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2011;41(5):574-579. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.821

24. Wert SR, Salovey P. A social comparison account of gossip. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):122-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.122

25. Peters K, Kashima Y. From social talk to social action: shaping the social triad with emotion sharing. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(5):780-797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.780

26. Cruz TDD, Beersma B, Dijkstra MTM, Bechtoldt MN. The bright and dark side of gossip for cooperation in groups. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01374

27. Connolly R. The year in gossip. Hazlitt. December 4, 2020. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://hazlitt.net/feature/year-gossip

28. Rosenbluth G, Good BP, Litterer KP, et al. Communicating effectively with hospitalized patients and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):440-442. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3466

29. Feinberg M, Willer R, Stellar J, Keltner D. The virtues of gossip: reputational information sharing as prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(5):1015-1030. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026650

30. Panchanathan K, Boyd R. Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature. 2004;432(7016):499-502. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02978

31. Suls JM. Gossip as social comparison. J Commun. 1977;27(1):164-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01812.x

32. Gottfriend S. The science behind why people gossip—and when it can be a good thing. Time. September 25, 2019. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://time.com/5680457/why-do-people-gossip/

33. Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Greysen SR, et al. Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):483-488. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3476

34. Skinner BF. Science and Human Behavior. The Macmillan Company; 1953.

35. Andrzejewski ME, Cardinal CD, Field DP, et al. Pigeons’ choices between fixed-interval and random-interval schedules: utility of variability? J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;83(2):129-145. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2005.30-04

36. Kendall SB. Preference for intermittent reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974;21(3):463-473. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1974.21-463

37. Redelmeier DA, Ross LD. Pitfalls from psychology science that worsen with practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3050-3052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05864-5

38. Rosnow RL. Inside rumor: a personal journey. Am Psychol. 1991;46(5):484-496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.5.484

39. Cinelli M, De Francisci Moreales G, Galeazzi A, Quattrociocchi W, Starnini M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(9):e2023301118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

40. Chaikof M, Tannenbaum E, Mathur S, Bodley J, Farrugia M. Approaching gossip and rumor in medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):239-240. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00119.1

41. Redelmeier DA, Najeeb U, Etchells EE. Understanding patient personality in medical care: five-factor model. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):2111-2114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06598-8

42. Ribeiro VE, Blakeley JA. The proactive management of rumor and gossip. J Nurs Adm. 1995;25(6):43-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-199506000-00010

43. Beersma B, van Kleef GA. Why people gossip: an empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(11):2640-2670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00956.x

CLINICAL SCENARIO PROLOGUE

You are signing over to a colleague on the COVID-19 inpatient hospital ward. You are stressed after having failed to reach the chief medical resident who did not respond despite repeated texts. You think about mentioning this apparent professional lapse to your colleague. You pause, however, because you are uncertain about the appropriate norm, hesitant around finding the right words, and unsure about a mutual feeling of camaraderie.

OVERVIEW

Lay and scientific perspectives about gossip diverge widely. Lay definitions of gossip generally include malicious, salacious, immoral, trivial, or unfair comments that attack someone else’s reputation. Scientific definitions of gossip, in contrast, also include neutral or positive social information intended to align group dynamics.1 The common feature of both is that the named individual is not present to hear about themselves.2 A further commonality is that gossip involves informal assessments loaded with subjective judgments, unlike professional comments about patients from clinicians providing care. In contrast to stereotype remarks, gossip focuses on a specific person and not a group.

Gossip is widespread. A recent study in nonhospital settings suggests nearly all adults engage in gossip during normal interactions, averaging 52 minutes on a typical day.3 Most gossip is neutral (74%) rather than negative or positive. The content usually (92%) concerns relationships, and the typical person identified (82%) is an acquaintance. Some of the potential benefits include conveying information for social learning, defining what is socially acceptable, or promoting personal connections. Men and women gossip to nearly the same degree.4 Indeed, evolutionary theory suggests gossip is not deviant behavior and arises even in small hunter-gatherer communities.5Social psychology science provides some insights on fundamental principles of gossip that may be relevant to clinicians in medicine.6 In this article, we review three important findings from social psychology science relevant to team cooperation, the specific transmitter, and the individual receiver (Table 1). Clinicians working in groups may benefit from recognizing the prosocial function of healthy gossip and avoiding the antisocial adverse effects of harmful gossip.7 At a time when work-related conversations have radically shifted online,8 hospitalists need to be aware of positives and pitfalls of gossip to help provide effective medical care and avoid adverse events.

GOSSIP AS TEAM COMMUNICATION

Large team endeavors often require social signals to coordinate people.9 Gossip helps groups establish reputations, monitor their members, deter antisocial behavior, and protect newcomers from exploitation.10 Sharing social information can also indirectly promote cooperation because individuals place a high value on their own reputations and want to avoid embarrassment.11,12 The absence of gossip, in contrast, may lead individuals to be oblivious to team expectations and fail to do their fair share. A lack of gossip, in particular, may add to inefficiencies during the COVID-19 pandemic since exchanging gossip seems to feel awkward over email or other digital channels (albeit a chat function for side conversations in virtual meetings is a partial substitute).13,14

A paradigm for testing the positive effects of gossip involves a trust game where participants consider making small contributions for later rewards in recurrent rounds of cooperation.15-17 In one online study of volunteers, for example, individuals contributed to a group account and gained rewards equal to a doubling of total contributions shared over everyone equally (even those contributing nothing).18 Half the experiments allowed participants to send notes about other participants, whereas the other experiments allowed no such “gossip.” As predicted, gossip increased the proportion contributed (40% vs 32%, P = .020) and average total reward (64 vs 56, P = .002). In this and other studies of healthy volunteers, gossip builds trust and increases gains for the entire group.19-22

Effective medical practice inside hospitals often involves constructive gossip for pointers on how to behave (eg, how quickly to reply to a text message from the ward pharmacist). The blend of objective facts with subjective opinion provides a compelling message otherwise lacking from institutional guidelines or directives on how not to behave (eg, how quickly to complete an annual report with an arbitrary deadline). Gossip is the antithesis of a cursory interaction between strangers and is also less awkward than open flattery or public ridicule that may occur when the third person is in earshot.23 Even negative social comparisons can be constructive to listeners since people want to know how to avoid bad gossip about themselves in a world with changing morality.24

GOSSIP AND THE TRANSMITTER

Gossip can provide a distinct emotional benefit for the gossiper as a form of self-expression, an exercise of justice, and a validation of one’s perspective.25 Consider, for example, witnessing an antisocial act that leads to subsequent feelings of unfairness yet having no way to communicate personal dissatisfaction. Similarly, expressing prosocial gossip may help relieve some of the annoyance after a hassle (eg, talking with a friend after encountering a new onerous hospital protocol). The sharing of gossip might also help bolster solidarity after an offense (eg, talking with a friend on how to deal with another warning from health records).26 In contrast, lost opportunities to gossip about unfairness could be exacerbating the social isolation and emotional distress of the COVID-19 pandemic.27,28

A rigorous example of the emotional benefits of expressing gossip involves undergraduates witnessing staged behavior under laboratory conditions where one actor appeared to exploit the generosity of another actor.29 By random assignment, half the participants had an opportunity to gossip, and the other half had no such opportunity. All participants reacted to the antisocial behavior by feeling frustrated (self-report survey scale of 0-100, where higher scores indicate worse frustration). Importantly, almost all chose to engage in gossip when feasible, and those who had the opportunity to gossip experienced more relief than those who had no opportunity (absolute improvement in frustration scores, 9.69 vs 0.16; P < .01). Evidentially, engaging in prosocial gossip can sometimes provide solace.

Sharing gossip might strengthen social bonds, bolster self-esteem, promote personal power, elicit reciprocal favors, or telegraph the presence of a larger network of personal connections. Gossip is cheap and efficient compared with peer-sanctioning or formal sanctioning to control behavior.30 Airing grievances through gossip may also solve some social dilemmas more easily than channeling messages through institutional reporting structures or formal performance reviews. Gossip has another advantage of raising delicate comparative judgments without the discomfort of direct confrontation (eg, defining the appropriate level of detail for a case presentation is perhaps best done by identifying those who are judged too verbose).31

GOSSIP AND THE RECEIVER

People tend to enjoy listening to gossip despite the uneven quality where some comments are more valuable than others. The receiver, therefore, faces an irregular payoff similar to random intermittent reinforcement. Ironically, random intermittent reinforcement can be particularly addictive when compared with steady rewards with predictable payoffs. This includes cases where gossip conveys good news that helps elevate, inspire, or motivate the receiver. The thirst for more gossip may partially explain why receivers keep seeking gossip despite knowing the material may be unimportant. The shortfall of enticing gossip might also be another factor adding to a feeling of loneliness that prevails widely during the COVID-19 pandemic.32,33

Classic research on reinforcement includes experiments examining operant conditioning for creating addiction.34,35 An important distinction is the contrast between random reinforcement (eg, variable reward akin to gambling on a roulette wheel) and consistent reinforcement (eg, regular pay akin to a steady salary each week). In a study of pigeons trained to peck a lever for food, for example, random reinforcement resulted in twice the response compared with consistent reinforcement (despite an equalized total amount of food received).36 Moreover, random reinforcement was hard to extinguish, and the behavior continued long after all food ended. In general, random compared with consistent reinforcement tended to cause a more intense and persistent change of behavior.

The inconsistent quality makes the prospect of new, exciting gossip seem nearly impossible to resist; indeed, gossip from any source is surprisingly tantalizing. Moreover, the validity of gossip is rarely challenged, unlike the typical norm of lively thoughtful debate that surrounds new ideas (eg, whether to prescribe a novel medication).2 Gossip, of course, can also lead to a positive thrill where, for example, a recipient subsequently feels emboldened with passionate enthusiasm to relay the point to others. This means that spreading inaccurate characterizations may be particularly destructive for a listener who is gullible or easily provoked.37 Conversely, gossip can also lead to anxiety about future uncertainties.38

DISCUSSION

This perspective summarizes positive and negative features of gossip drawn from social psychology science on a normally hidden activity. The main benefits in medical care are to support team communication, the specific transmitter, and the individual receiver. Some specific gains are to enhance team cooperation, deter exploitation, signal trust, and convey codes of conduct. Sharing gossip might also promote honest dialogue, foster friendships, facilitate reciprocity, and curtail excessive use of force by a dominant individual. Listening to gossip possibly also reduces loneliness, affirms an innate desire for inclusion, and provides a way to share insights. Of course, gossip has downsides from direct or indirect adverse effects that merit attention and mitigation (Table 2).

A large direct downside of gossip is in propagating damaging misinformation that harms individuals.24 Toxic gossip can wreck relationships, hurt feelings, violate privacy, and manipulate others. Malicious gossip may become further accentuated because of groupthink, polarization, or selfish biases.39 Presumably, these downsides of gossip are sufficiently infrequent because regular people spend substantial time, attention, and effort engaging in gossip.3 In society, healthy gossip that propagates positive information goes by synonyms having a less negative connotation, including socializing, networking, chatting, schmoozing, friendly banter, small talk, and scuttlebutt. The net benefits must be real since one person is often both a transmitter and a receiver of gossip over time.

Another large direct limitation of gossip is that it can magnify social inequities by allowing some people but not others to access hidden information. In essence, receiving gossip is a privilege that is not universally available within a community and depends on social capital.40 Gossip helps strengthen personal bonds, so marginalized individuals can become further disempowered by not receiving gossip. Social exclusion is painful when different individuals realize they are left out of gossip circles. In summary, gossip can provide an unfair advantage because it allows only some people to learn what is going on behind their backs (eg, different hospitalists within the same institution may have differing circles of friendships for different professional advantages).

Gossip is a way to communicate priorities and regulate behavior. Without interpersonal comparisons, clinicians might find themselves adrift in a complex, difficult, and mysterious medical world. Listening to intelligent gossip can also be an effective way to learn lessons that are otherwise difficult to grasp (eg, an impolite comment may be more easily recognized in someone else than in yourself).41 Perhaps this explains why hospital executives gossip about physicians and vice versa.42 Healthy gossip tends to be positive or neutral (not malicious or negative), propagates accurate information (not hurtful falsehoods), and corrects social inequities (not worsening unearned privileges).43 We suggest that a careful practice of healthy gossip may help regulate trust, enhance social bonding, shape how people feel working together, and promote collective benefit.

CLINICAL SCENARIO EPILOGUE

Your colleague spontaneously comments that the chief medical resident is away because of a death in the family. In turn, you realize you were unaware of this personal nuance because the point was unmentioned in the (virtual) staff meeting last week. You thank your colleague for tactfully relaying the point. You also secretly wonder what other interpersonal details you might be missing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cindy Kao, Fizza Manzoor, Sheharyar Raza, Lee Ross, Miriam Shuchman, and William Silverstein for helpful suggestions on specific points.

CLINICAL SCENARIO PROLOGUE

You are signing over to a colleague on the COVID-19 inpatient hospital ward. You are stressed after having failed to reach the chief medical resident who did not respond despite repeated texts. You think about mentioning this apparent professional lapse to your colleague. You pause, however, because you are uncertain about the appropriate norm, hesitant around finding the right words, and unsure about a mutual feeling of camaraderie.

OVERVIEW

Lay and scientific perspectives about gossip diverge widely. Lay definitions of gossip generally include malicious, salacious, immoral, trivial, or unfair comments that attack someone else’s reputation. Scientific definitions of gossip, in contrast, also include neutral or positive social information intended to align group dynamics.1 The common feature of both is that the named individual is not present to hear about themselves.2 A further commonality is that gossip involves informal assessments loaded with subjective judgments, unlike professional comments about patients from clinicians providing care. In contrast to stereotype remarks, gossip focuses on a specific person and not a group.

Gossip is widespread. A recent study in nonhospital settings suggests nearly all adults engage in gossip during normal interactions, averaging 52 minutes on a typical day.3 Most gossip is neutral (74%) rather than negative or positive. The content usually (92%) concerns relationships, and the typical person identified (82%) is an acquaintance. Some of the potential benefits include conveying information for social learning, defining what is socially acceptable, or promoting personal connections. Men and women gossip to nearly the same degree.4 Indeed, evolutionary theory suggests gossip is not deviant behavior and arises even in small hunter-gatherer communities.5Social psychology science provides some insights on fundamental principles of gossip that may be relevant to clinicians in medicine.6 In this article, we review three important findings from social psychology science relevant to team cooperation, the specific transmitter, and the individual receiver (Table 1). Clinicians working in groups may benefit from recognizing the prosocial function of healthy gossip and avoiding the antisocial adverse effects of harmful gossip.7 At a time when work-related conversations have radically shifted online,8 hospitalists need to be aware of positives and pitfalls of gossip to help provide effective medical care and avoid adverse events.

GOSSIP AS TEAM COMMUNICATION

Large team endeavors often require social signals to coordinate people.9 Gossip helps groups establish reputations, monitor their members, deter antisocial behavior, and protect newcomers from exploitation.10 Sharing social information can also indirectly promote cooperation because individuals place a high value on their own reputations and want to avoid embarrassment.11,12 The absence of gossip, in contrast, may lead individuals to be oblivious to team expectations and fail to do their fair share. A lack of gossip, in particular, may add to inefficiencies during the COVID-19 pandemic since exchanging gossip seems to feel awkward over email or other digital channels (albeit a chat function for side conversations in virtual meetings is a partial substitute).13,14

A paradigm for testing the positive effects of gossip involves a trust game where participants consider making small contributions for later rewards in recurrent rounds of cooperation.15-17 In one online study of volunteers, for example, individuals contributed to a group account and gained rewards equal to a doubling of total contributions shared over everyone equally (even those contributing nothing).18 Half the experiments allowed participants to send notes about other participants, whereas the other experiments allowed no such “gossip.” As predicted, gossip increased the proportion contributed (40% vs 32%, P = .020) and average total reward (64 vs 56, P = .002). In this and other studies of healthy volunteers, gossip builds trust and increases gains for the entire group.19-22

Effective medical practice inside hospitals often involves constructive gossip for pointers on how to behave (eg, how quickly to reply to a text message from the ward pharmacist). The blend of objective facts with subjective opinion provides a compelling message otherwise lacking from institutional guidelines or directives on how not to behave (eg, how quickly to complete an annual report with an arbitrary deadline). Gossip is the antithesis of a cursory interaction between strangers and is also less awkward than open flattery or public ridicule that may occur when the third person is in earshot.23 Even negative social comparisons can be constructive to listeners since people want to know how to avoid bad gossip about themselves in a world with changing morality.24

GOSSIP AND THE TRANSMITTER

Gossip can provide a distinct emotional benefit for the gossiper as a form of self-expression, an exercise of justice, and a validation of one’s perspective.25 Consider, for example, witnessing an antisocial act that leads to subsequent feelings of unfairness yet having no way to communicate personal dissatisfaction. Similarly, expressing prosocial gossip may help relieve some of the annoyance after a hassle (eg, talking with a friend after encountering a new onerous hospital protocol). The sharing of gossip might also help bolster solidarity after an offense (eg, talking with a friend on how to deal with another warning from health records).26 In contrast, lost opportunities to gossip about unfairness could be exacerbating the social isolation and emotional distress of the COVID-19 pandemic.27,28

A rigorous example of the emotional benefits of expressing gossip involves undergraduates witnessing staged behavior under laboratory conditions where one actor appeared to exploit the generosity of another actor.29 By random assignment, half the participants had an opportunity to gossip, and the other half had no such opportunity. All participants reacted to the antisocial behavior by feeling frustrated (self-report survey scale of 0-100, where higher scores indicate worse frustration). Importantly, almost all chose to engage in gossip when feasible, and those who had the opportunity to gossip experienced more relief than those who had no opportunity (absolute improvement in frustration scores, 9.69 vs 0.16; P < .01). Evidentially, engaging in prosocial gossip can sometimes provide solace.

Sharing gossip might strengthen social bonds, bolster self-esteem, promote personal power, elicit reciprocal favors, or telegraph the presence of a larger network of personal connections. Gossip is cheap and efficient compared with peer-sanctioning or formal sanctioning to control behavior.30 Airing grievances through gossip may also solve some social dilemmas more easily than channeling messages through institutional reporting structures or formal performance reviews. Gossip has another advantage of raising delicate comparative judgments without the discomfort of direct confrontation (eg, defining the appropriate level of detail for a case presentation is perhaps best done by identifying those who are judged too verbose).31

GOSSIP AND THE RECEIVER

People tend to enjoy listening to gossip despite the uneven quality where some comments are more valuable than others. The receiver, therefore, faces an irregular payoff similar to random intermittent reinforcement. Ironically, random intermittent reinforcement can be particularly addictive when compared with steady rewards with predictable payoffs. This includes cases where gossip conveys good news that helps elevate, inspire, or motivate the receiver. The thirst for more gossip may partially explain why receivers keep seeking gossip despite knowing the material may be unimportant. The shortfall of enticing gossip might also be another factor adding to a feeling of loneliness that prevails widely during the COVID-19 pandemic.32,33

Classic research on reinforcement includes experiments examining operant conditioning for creating addiction.34,35 An important distinction is the contrast between random reinforcement (eg, variable reward akin to gambling on a roulette wheel) and consistent reinforcement (eg, regular pay akin to a steady salary each week). In a study of pigeons trained to peck a lever for food, for example, random reinforcement resulted in twice the response compared with consistent reinforcement (despite an equalized total amount of food received).36 Moreover, random reinforcement was hard to extinguish, and the behavior continued long after all food ended. In general, random compared with consistent reinforcement tended to cause a more intense and persistent change of behavior.

The inconsistent quality makes the prospect of new, exciting gossip seem nearly impossible to resist; indeed, gossip from any source is surprisingly tantalizing. Moreover, the validity of gossip is rarely challenged, unlike the typical norm of lively thoughtful debate that surrounds new ideas (eg, whether to prescribe a novel medication).2 Gossip, of course, can also lead to a positive thrill where, for example, a recipient subsequently feels emboldened with passionate enthusiasm to relay the point to others. This means that spreading inaccurate characterizations may be particularly destructive for a listener who is gullible or easily provoked.37 Conversely, gossip can also lead to anxiety about future uncertainties.38

DISCUSSION

This perspective summarizes positive and negative features of gossip drawn from social psychology science on a normally hidden activity. The main benefits in medical care are to support team communication, the specific transmitter, and the individual receiver. Some specific gains are to enhance team cooperation, deter exploitation, signal trust, and convey codes of conduct. Sharing gossip might also promote honest dialogue, foster friendships, facilitate reciprocity, and curtail excessive use of force by a dominant individual. Listening to gossip possibly also reduces loneliness, affirms an innate desire for inclusion, and provides a way to share insights. Of course, gossip has downsides from direct or indirect adverse effects that merit attention and mitigation (Table 2).

A large direct downside of gossip is in propagating damaging misinformation that harms individuals.24 Toxic gossip can wreck relationships, hurt feelings, violate privacy, and manipulate others. Malicious gossip may become further accentuated because of groupthink, polarization, or selfish biases.39 Presumably, these downsides of gossip are sufficiently infrequent because regular people spend substantial time, attention, and effort engaging in gossip.3 In society, healthy gossip that propagates positive information goes by synonyms having a less negative connotation, including socializing, networking, chatting, schmoozing, friendly banter, small talk, and scuttlebutt. The net benefits must be real since one person is often both a transmitter and a receiver of gossip over time.

Another large direct limitation of gossip is that it can magnify social inequities by allowing some people but not others to access hidden information. In essence, receiving gossip is a privilege that is not universally available within a community and depends on social capital.40 Gossip helps strengthen personal bonds, so marginalized individuals can become further disempowered by not receiving gossip. Social exclusion is painful when different individuals realize they are left out of gossip circles. In summary, gossip can provide an unfair advantage because it allows only some people to learn what is going on behind their backs (eg, different hospitalists within the same institution may have differing circles of friendships for different professional advantages).

Gossip is a way to communicate priorities and regulate behavior. Without interpersonal comparisons, clinicians might find themselves adrift in a complex, difficult, and mysterious medical world. Listening to intelligent gossip can also be an effective way to learn lessons that are otherwise difficult to grasp (eg, an impolite comment may be more easily recognized in someone else than in yourself).41 Perhaps this explains why hospital executives gossip about physicians and vice versa.42 Healthy gossip tends to be positive or neutral (not malicious or negative), propagates accurate information (not hurtful falsehoods), and corrects social inequities (not worsening unearned privileges).43 We suggest that a careful practice of healthy gossip may help regulate trust, enhance social bonding, shape how people feel working together, and promote collective benefit.

CLINICAL SCENARIO EPILOGUE

Your colleague spontaneously comments that the chief medical resident is away because of a death in the family. In turn, you realize you were unaware of this personal nuance because the point was unmentioned in the (virtual) staff meeting last week. You thank your colleague for tactfully relaying the point. You also secretly wonder what other interpersonal details you might be missing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cindy Kao, Fizza Manzoor, Sheharyar Raza, Lee Ross, Miriam Shuchman, and William Silverstein for helpful suggestions on specific points.

1. Foster EK. Research on gossip: taxonomy, methods, and future directions. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):78-99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.78

2. Eder D, Enke JL. The structure of gossip: opportunities and constraints on collective expression among adolescents. Am Sociol Rev. 1991;56(4):494-508. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096270

3. Robbins ML, Karan A. Who gossips and how in everyday life. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(2):185-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619837000

4. Nevo O, Nevo B, Derech-Zehavi A. The development of the Tendency to Gossip Questionnaire: construct and concurrent validation for a sample of Israeli college students. Educ Psychol Meas. 1993;53(4):973-981. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053004010

5. Nishi A. Evolution and social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:132-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.015

6. Redelmeier DA, Ross LD. Practicing medicine with colleagues: pitfalls from social psychology science. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):624-626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04839-5

7. Baumeister RF, Zhang L, Vohs KD. Gossip as cultural learning. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):111-121. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.111

8. Kulkarni A. Navigating loneliness in the era of virtual care. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):307-309. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1813713

9. Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291-1298. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04131

10. Dunbar RIM. Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):100-110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100

11. Emler N. A social psychology of reputation. Eur Rev Social Psychol. 2011;1(1):171-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779108401861

12. Arendt F, Forrai M, Findl O. Dealing with negative reviews on physician-rating websites: an experimental test of how physicians can prevent reputational damage via effective response strategies. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113422

13. Seo H. Blah blah blah: the lack of small talk is breaking our brains. The Walrus. April 22, 2021. Updated April 22, 2021. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://thewalrus.ca/blah-blah-blah-the-lack-of-small-talk-is-breaking-our-brains/

14. Houchens N, Tipirneni R. Compassionate communication amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):437-439. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3472

15. Camerer CE. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton University Press; 2003.

16. Sommerfeld RD, Krambeck HJ, Semmann D, Milinski M. Gossip as an alternative for direct observation in games of indirect reciprocity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(44):17435-17440. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0704598104

17. Hendriks A. SoPHIE - Software Platform for Human Interaction Experiments. Working Paper. 2012.

18. Wu J, Balliet D, Van Lange PAM. Gossip versus punishment: the efficiency of reputation to promote and maintain cooperation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23919. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23919

19. Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. Reputation helps solve the “tragedy of the commons.” Nature. 2002;415(6870):424-426. https://doi.org/10.1038/415424a

20. Bolton GE, Katok E, Ockenfels A. Cooperation among strangers with limited information about reputation. J Publ Econ. 2005;89(8):1457-1468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.03.008

21. Seinen I, Schram A. Social status and group norms: indirect reciprocity in a repeated helping experiment. Eur Econ Rev. 2006;50(3):581-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.10.005

22. Feinberg M, Willer R, Schultz M. Gossip and ostracism promote cooperation in groups. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(3):656-664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613510184

23. Farley SD. Is gossip power? The inverse relationships between gossip, power, and likability. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2011;41(5):574-579. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.821

24. Wert SR, Salovey P. A social comparison account of gossip. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):122-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.122

25. Peters K, Kashima Y. From social talk to social action: shaping the social triad with emotion sharing. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(5):780-797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.780

26. Cruz TDD, Beersma B, Dijkstra MTM, Bechtoldt MN. The bright and dark side of gossip for cooperation in groups. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01374

27. Connolly R. The year in gossip. Hazlitt. December 4, 2020. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://hazlitt.net/feature/year-gossip

28. Rosenbluth G, Good BP, Litterer KP, et al. Communicating effectively with hospitalized patients and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):440-442. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3466

29. Feinberg M, Willer R, Stellar J, Keltner D. The virtues of gossip: reputational information sharing as prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(5):1015-1030. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026650

30. Panchanathan K, Boyd R. Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature. 2004;432(7016):499-502. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02978

31. Suls JM. Gossip as social comparison. J Commun. 1977;27(1):164-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01812.x

32. Gottfriend S. The science behind why people gossip—and when it can be a good thing. Time. September 25, 2019. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://time.com/5680457/why-do-people-gossip/

33. Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Greysen SR, et al. Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):483-488. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3476

34. Skinner BF. Science and Human Behavior. The Macmillan Company; 1953.

35. Andrzejewski ME, Cardinal CD, Field DP, et al. Pigeons’ choices between fixed-interval and random-interval schedules: utility of variability? J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;83(2):129-145. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2005.30-04

36. Kendall SB. Preference for intermittent reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974;21(3):463-473. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1974.21-463

37. Redelmeier DA, Ross LD. Pitfalls from psychology science that worsen with practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3050-3052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05864-5

38. Rosnow RL. Inside rumor: a personal journey. Am Psychol. 1991;46(5):484-496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.5.484

39. Cinelli M, De Francisci Moreales G, Galeazzi A, Quattrociocchi W, Starnini M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(9):e2023301118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

40. Chaikof M, Tannenbaum E, Mathur S, Bodley J, Farrugia M. Approaching gossip and rumor in medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):239-240. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00119.1

41. Redelmeier DA, Najeeb U, Etchells EE. Understanding patient personality in medical care: five-factor model. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):2111-2114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06598-8

42. Ribeiro VE, Blakeley JA. The proactive management of rumor and gossip. J Nurs Adm. 1995;25(6):43-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-199506000-00010

43. Beersma B, van Kleef GA. Why people gossip: an empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(11):2640-2670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00956.x

1. Foster EK. Research on gossip: taxonomy, methods, and future directions. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):78-99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.78

2. Eder D, Enke JL. The structure of gossip: opportunities and constraints on collective expression among adolescents. Am Sociol Rev. 1991;56(4):494-508. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096270

3. Robbins ML, Karan A. Who gossips and how in everyday life. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(2):185-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619837000

4. Nevo O, Nevo B, Derech-Zehavi A. The development of the Tendency to Gossip Questionnaire: construct and concurrent validation for a sample of Israeli college students. Educ Psychol Meas. 1993;53(4):973-981. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053004010

5. Nishi A. Evolution and social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:132-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.015

6. Redelmeier DA, Ross LD. Practicing medicine with colleagues: pitfalls from social psychology science. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):624-626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04839-5

7. Baumeister RF, Zhang L, Vohs KD. Gossip as cultural learning. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):111-121. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.111

8. Kulkarni A. Navigating loneliness in the era of virtual care. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):307-309. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1813713

9. Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291-1298. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04131

10. Dunbar RIM. Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):100-110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100

11. Emler N. A social psychology of reputation. Eur Rev Social Psychol. 2011;1(1):171-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779108401861

12. Arendt F, Forrai M, Findl O. Dealing with negative reviews on physician-rating websites: an experimental test of how physicians can prevent reputational damage via effective response strategies. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113422

13. Seo H. Blah blah blah: the lack of small talk is breaking our brains. The Walrus. April 22, 2021. Updated April 22, 2021. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://thewalrus.ca/blah-blah-blah-the-lack-of-small-talk-is-breaking-our-brains/

14. Houchens N, Tipirneni R. Compassionate communication amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):437-439. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3472

15. Camerer CE. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton University Press; 2003.

16. Sommerfeld RD, Krambeck HJ, Semmann D, Milinski M. Gossip as an alternative for direct observation in games of indirect reciprocity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(44):17435-17440. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0704598104

17. Hendriks A. SoPHIE - Software Platform for Human Interaction Experiments. Working Paper. 2012.

18. Wu J, Balliet D, Van Lange PAM. Gossip versus punishment: the efficiency of reputation to promote and maintain cooperation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23919. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23919

19. Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. Reputation helps solve the “tragedy of the commons.” Nature. 2002;415(6870):424-426. https://doi.org/10.1038/415424a

20. Bolton GE, Katok E, Ockenfels A. Cooperation among strangers with limited information about reputation. J Publ Econ. 2005;89(8):1457-1468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.03.008

21. Seinen I, Schram A. Social status and group norms: indirect reciprocity in a repeated helping experiment. Eur Econ Rev. 2006;50(3):581-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.10.005

22. Feinberg M, Willer R, Schultz M. Gossip and ostracism promote cooperation in groups. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(3):656-664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613510184

23. Farley SD. Is gossip power? The inverse relationships between gossip, power, and likability. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2011;41(5):574-579. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.821

24. Wert SR, Salovey P. A social comparison account of gossip. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):122-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.122

25. Peters K, Kashima Y. From social talk to social action: shaping the social triad with emotion sharing. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(5):780-797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.780

26. Cruz TDD, Beersma B, Dijkstra MTM, Bechtoldt MN. The bright and dark side of gossip for cooperation in groups. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01374

27. Connolly R. The year in gossip. Hazlitt. December 4, 2020. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://hazlitt.net/feature/year-gossip

28. Rosenbluth G, Good BP, Litterer KP, et al. Communicating effectively with hospitalized patients and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):440-442. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3466

29. Feinberg M, Willer R, Stellar J, Keltner D. The virtues of gossip: reputational information sharing as prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(5):1015-1030. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026650

30. Panchanathan K, Boyd R. Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature. 2004;432(7016):499-502. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02978

31. Suls JM. Gossip as social comparison. J Commun. 1977;27(1):164-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01812.x

32. Gottfriend S. The science behind why people gossip—and when it can be a good thing. Time. September 25, 2019. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://time.com/5680457/why-do-people-gossip/

33. Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Greysen SR, et al. Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):483-488. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3476

34. Skinner BF. Science and Human Behavior. The Macmillan Company; 1953.

35. Andrzejewski ME, Cardinal CD, Field DP, et al. Pigeons’ choices between fixed-interval and random-interval schedules: utility of variability? J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;83(2):129-145. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2005.30-04

36. Kendall SB. Preference for intermittent reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974;21(3):463-473. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1974.21-463

37. Redelmeier DA, Ross LD. Pitfalls from psychology science that worsen with practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3050-3052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05864-5

38. Rosnow RL. Inside rumor: a personal journey. Am Psychol. 1991;46(5):484-496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.5.484

39. Cinelli M, De Francisci Moreales G, Galeazzi A, Quattrociocchi W, Starnini M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(9):e2023301118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

40. Chaikof M, Tannenbaum E, Mathur S, Bodley J, Farrugia M. Approaching gossip and rumor in medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):239-240. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00119.1

41. Redelmeier DA, Najeeb U, Etchells EE. Understanding patient personality in medical care: five-factor model. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):2111-2114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06598-8

42. Ribeiro VE, Blakeley JA. The proactive management of rumor and gossip. J Nurs Adm. 1995;25(6):43-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-199506000-00010

43. Beersma B, van Kleef GA. Why people gossip: an empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(11):2640-2670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00956.x

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine