User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

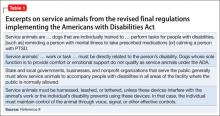

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

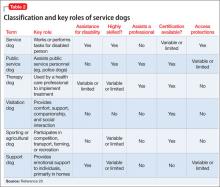

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).