User login

The end of the line: Concluding your practice when facing serious illness

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27

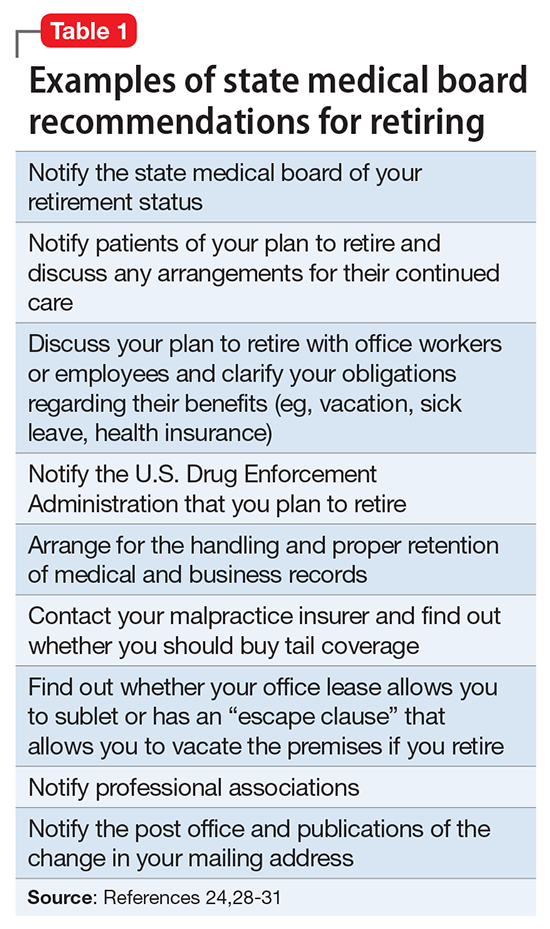

Further obligations come from medical licensing boards, which, in many states, have established time frames and specific procedures for informing patients and the public when a physician is leaving practice. Table 124,28-31 lists examples of these. If Dr. F works in a state where the board hasn’t promulgated such regulations, Table 124,28-31 may still help him think through how to discharge his ethical responsibilities to notify patients, colleagues, and business entities that he is ending his practice. References 28-30 and 32 discuss several of these matters, suggest timetables for various steps of a practice closure, and provide sample letters for notifying patients.

Physicians also must preserve their medical records for a certain period after they retire. States with rules on this matter require record preservation for 5 to 10 years or until 2 or 3 years after minor patients reach the age of majority.33 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 requires covered entities, which include most psychiatrists, to retain records for 6 years,34 and certain Medicare programs require retention for 10 years.35

Depending on Dr. F’s location and type of practice, his records should be preserved for the longest period that applies. If he is leaving a group practice that owns the records, arranging for this should be easy. If leaving an independent practice, he may need to ask another practice to perform this function.25

A ‘professional will’

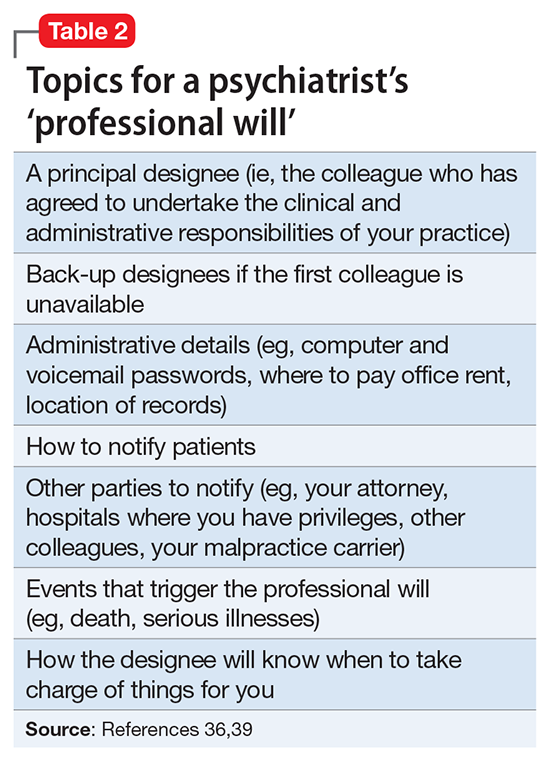

Dr. F also might consider a measure that many psychotherapists recommend13,19,36 and that in some states is required by mental health licensing boards or professional codes37,38: creating a “professional will” that contains instructions for handling practice matters in case of death or disability.39

1. LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, et al. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(6):445-454.

2. Dellinger EP, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):967-971.

3. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G. The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):233-239.

5. Merenstein B, Merenstein J. Patient reflections: saying good-bye to a retiring family doctor. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):461-465.

6. Lord R, Ritvo S, Solnit AJ. Patients’ reactions to the death of the psychoanalyst. Intern J Psychoanal. 1978;59(2-3):189-197.

7. Power A. Forced endings in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: attachment and loss in retirement. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

8. Robutti A. When the patient loses his/her analyst. Italian Psychoanalytic Annual. 2010;4:129-145.

9. Traesdal T. When the analyst dies: dealing with the aftermath. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53(4):1235-1255.

10. Deutsch RA. A voice lost, a voice found: after the death of the analyst. In: Deutsch RA, ed. Traumatic ruptures: abandonment and betrayal in the analytic relationship. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:32-45.

11. Ward VP. On Yoda, trouble, and transformation: the cultural context of therapy and supervision. Contemp Fam Ther. 2009;31(3):171-176.

12. Moffic HS. Mental bootcamp: today is the first day of your retirement! Psychiatr Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/blogs/couch-crisis/mental-bootcamp-today-first-day-your-retirement. Published June 25, 2012. Accessed October 31, 2017.

13. Shatsky P. Everything ends: identity and the therapist’s retirement. Clin Soc Work J. 2016;44(2):143-149.

14. Collier R.

15. Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, et al. Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):794-801.

16. Silver MP. Critical reflection on physician retirement. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):783-784.

17. Clemens NA. A psychiatrist retires: an oxymoron? J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(5):351-354.

18. Packard FR. The earliest hospitals. In: Packard FR. History of medicine in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1901:348.

19. Galatzer-Levy RM. The death of the analyst: patients whose previous analyst died while they were in treatment. J Amer Psychoanalytic Assoc. 2004;52(4):999-1024.

20. Fajardo B. Life-threatening illness in the analyst. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2001;49(2):569-586.

21. Dewald PA. Serious illness in the analyst: transference, countertransference, and reality responses. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1982;30(2):347-363.

22. Howe E. Should psychiatrists self disclose? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(12):14-17.

23. Rizq R, Voller D. ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ On the death of a psychoanalyst. Psychodyn Pract. 2013;19(2):143-167.

24. Babitsky S, Mangraviti JJ. The biggest legal mistakes physicians make—and how to avoid them. Falmouth, MA: SEAK, Inc.; 2005.

25. Armon BD, Bayus K. Legal considerations when making a practice change. Chest. 2014;146(1):215-219.

26. American Medical Association. Opinions on patient-physician relationships: 1.1.5 terminating a patient-physician relationship. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 29, 2017.

27. Lee v Dewbre, 362 S.W. 2d 900 (Tex Civ App 7th Dist 1962).

28. Medical Association of Georgia. Issues for the retiring physician. https://www.mag.org/georgia/uploadedfiles/issues-retiring-physicians.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2017.

29. Massachusetts Medical Society. Issues for the retiring physician. http://www.massmed.org/physicians/practice-management/practice-ownership-and-operations/issues-for-the-retiring-physician-(pdf). Published 2012. Accessed October 1, 2017.

30. North Carolina Medical Board. The doctor is out: a physician’s guide to closing a practice. https://www.ncmedboard.org/images/uploads/article_images/Physicians_Guide_to_Closing_a_Practice_05_12_2014.pdf. Published May 12, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

31. 243 Code of Mass. Regulations §2.06(4)(a).

32. Sampson K. Physician’s guide to closing a practice. Maine Medical Association. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/Closing%20Practice%20Guide%20FINAL%206.2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

33. HealthIT.gov. State medical record laws: minimum medical record retention periods for records held by medical doctors and hospitals. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/appa7-1.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2017.

34. 45 CFR §164.316(b)(2).

35. 42 CFR §422.504(d)(2)(iii).

36. Pope KS, Vasquez MJT. How to survive and thrive as a therapist: information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

37. Becher EH, Ogasawara T, Harris SM. Death of a clinician: the personal, practical and clinical implications of therapist mortality. Contemp Fam Ther. 2012;34(3):313-321.

38. Hovey JK. Mortality practices: how clinical social workers interact with their mortality within their clinical and professional practice. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.Paper 1081. http://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=theses. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

39. Frankel AS, Alban A. Professional wills: protecting patients, family members and colleagues. The Steve Frankel Group. https://www.sfrankelgroup.com/professional-wills.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

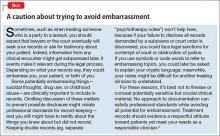

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27

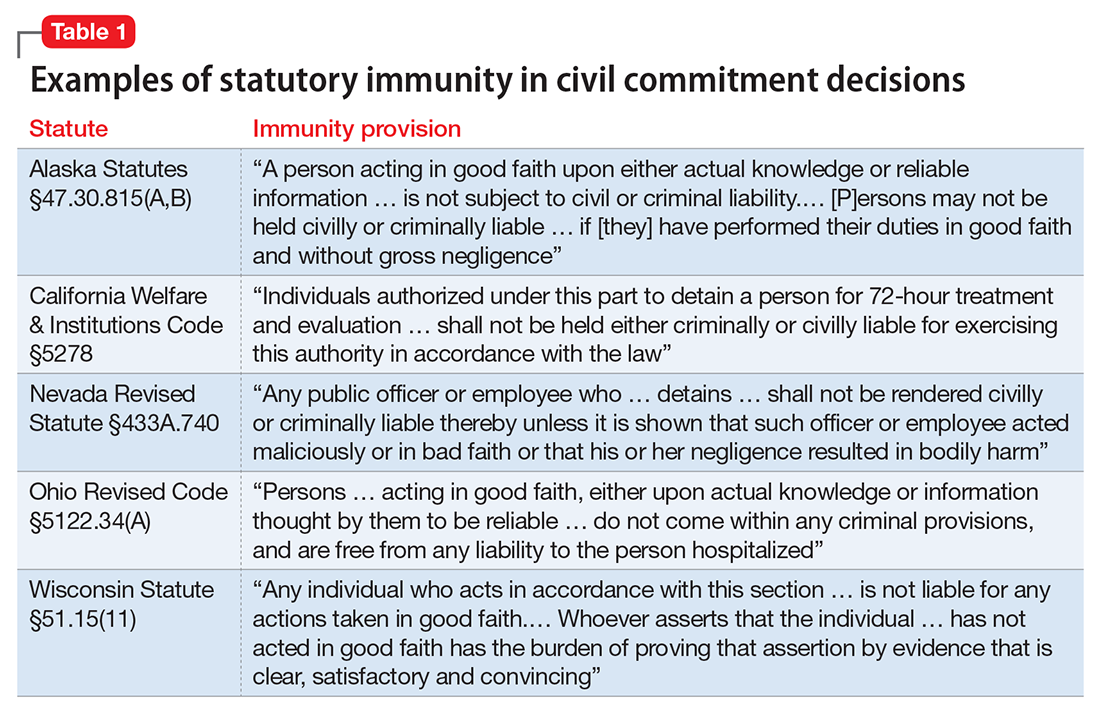

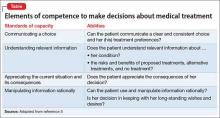

Further obligations come from medical licensing boards, which, in many states, have established time frames and specific procedures for informing patients and the public when a physician is leaving practice. Table 124,28-31 lists examples of these. If Dr. F works in a state where the board hasn’t promulgated such regulations, Table 124,28-31 may still help him think through how to discharge his ethical responsibilities to notify patients, colleagues, and business entities that he is ending his practice. References 28-30 and 32 discuss several of these matters, suggest timetables for various steps of a practice closure, and provide sample letters for notifying patients.

Physicians also must preserve their medical records for a certain period after they retire. States with rules on this matter require record preservation for 5 to 10 years or until 2 or 3 years after minor patients reach the age of majority.33 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 requires covered entities, which include most psychiatrists, to retain records for 6 years,34 and certain Medicare programs require retention for 10 years.35

Depending on Dr. F’s location and type of practice, his records should be preserved for the longest period that applies. If he is leaving a group practice that owns the records, arranging for this should be easy. If leaving an independent practice, he may need to ask another practice to perform this function.25

A ‘professional will’

Dr. F also might consider a measure that many psychotherapists recommend13,19,36 and that in some states is required by mental health licensing boards or professional codes37,38: creating a “professional will” that contains instructions for handling practice matters in case of death or disability.39

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27

Further obligations come from medical licensing boards, which, in many states, have established time frames and specific procedures for informing patients and the public when a physician is leaving practice. Table 124,28-31 lists examples of these. If Dr. F works in a state where the board hasn’t promulgated such regulations, Table 124,28-31 may still help him think through how to discharge his ethical responsibilities to notify patients, colleagues, and business entities that he is ending his practice. References 28-30 and 32 discuss several of these matters, suggest timetables for various steps of a practice closure, and provide sample letters for notifying patients.

Physicians also must preserve their medical records for a certain period after they retire. States with rules on this matter require record preservation for 5 to 10 years or until 2 or 3 years after minor patients reach the age of majority.33 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 requires covered entities, which include most psychiatrists, to retain records for 6 years,34 and certain Medicare programs require retention for 10 years.35

Depending on Dr. F’s location and type of practice, his records should be preserved for the longest period that applies. If he is leaving a group practice that owns the records, arranging for this should be easy. If leaving an independent practice, he may need to ask another practice to perform this function.25

A ‘professional will’

Dr. F also might consider a measure that many psychotherapists recommend13,19,36 and that in some states is required by mental health licensing boards or professional codes37,38: creating a “professional will” that contains instructions for handling practice matters in case of death or disability.39

1. LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, et al. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(6):445-454.

2. Dellinger EP, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):967-971.

3. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G. The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):233-239.

5. Merenstein B, Merenstein J. Patient reflections: saying good-bye to a retiring family doctor. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):461-465.

6. Lord R, Ritvo S, Solnit AJ. Patients’ reactions to the death of the psychoanalyst. Intern J Psychoanal. 1978;59(2-3):189-197.

7. Power A. Forced endings in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: attachment and loss in retirement. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

8. Robutti A. When the patient loses his/her analyst. Italian Psychoanalytic Annual. 2010;4:129-145.

9. Traesdal T. When the analyst dies: dealing with the aftermath. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53(4):1235-1255.

10. Deutsch RA. A voice lost, a voice found: after the death of the analyst. In: Deutsch RA, ed. Traumatic ruptures: abandonment and betrayal in the analytic relationship. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:32-45.

11. Ward VP. On Yoda, trouble, and transformation: the cultural context of therapy and supervision. Contemp Fam Ther. 2009;31(3):171-176.

12. Moffic HS. Mental bootcamp: today is the first day of your retirement! Psychiatr Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/blogs/couch-crisis/mental-bootcamp-today-first-day-your-retirement. Published June 25, 2012. Accessed October 31, 2017.

13. Shatsky P. Everything ends: identity and the therapist’s retirement. Clin Soc Work J. 2016;44(2):143-149.

14. Collier R.

15. Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, et al. Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):794-801.

16. Silver MP. Critical reflection on physician retirement. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):783-784.

17. Clemens NA. A psychiatrist retires: an oxymoron? J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(5):351-354.

18. Packard FR. The earliest hospitals. In: Packard FR. History of medicine in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1901:348.

19. Galatzer-Levy RM. The death of the analyst: patients whose previous analyst died while they were in treatment. J Amer Psychoanalytic Assoc. 2004;52(4):999-1024.

20. Fajardo B. Life-threatening illness in the analyst. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2001;49(2):569-586.

21. Dewald PA. Serious illness in the analyst: transference, countertransference, and reality responses. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1982;30(2):347-363.

22. Howe E. Should psychiatrists self disclose? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(12):14-17.

23. Rizq R, Voller D. ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ On the death of a psychoanalyst. Psychodyn Pract. 2013;19(2):143-167.

24. Babitsky S, Mangraviti JJ. The biggest legal mistakes physicians make—and how to avoid them. Falmouth, MA: SEAK, Inc.; 2005.

25. Armon BD, Bayus K. Legal considerations when making a practice change. Chest. 2014;146(1):215-219.

26. American Medical Association. Opinions on patient-physician relationships: 1.1.5 terminating a patient-physician relationship. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 29, 2017.

27. Lee v Dewbre, 362 S.W. 2d 900 (Tex Civ App 7th Dist 1962).

28. Medical Association of Georgia. Issues for the retiring physician. https://www.mag.org/georgia/uploadedfiles/issues-retiring-physicians.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2017.

29. Massachusetts Medical Society. Issues for the retiring physician. http://www.massmed.org/physicians/practice-management/practice-ownership-and-operations/issues-for-the-retiring-physician-(pdf). Published 2012. Accessed October 1, 2017.

30. North Carolina Medical Board. The doctor is out: a physician’s guide to closing a practice. https://www.ncmedboard.org/images/uploads/article_images/Physicians_Guide_to_Closing_a_Practice_05_12_2014.pdf. Published May 12, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

31. 243 Code of Mass. Regulations §2.06(4)(a).

32. Sampson K. Physician’s guide to closing a practice. Maine Medical Association. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/Closing%20Practice%20Guide%20FINAL%206.2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

33. HealthIT.gov. State medical record laws: minimum medical record retention periods for records held by medical doctors and hospitals. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/appa7-1.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2017.

34. 45 CFR §164.316(b)(2).

35. 42 CFR §422.504(d)(2)(iii).

36. Pope KS, Vasquez MJT. How to survive and thrive as a therapist: information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

37. Becher EH, Ogasawara T, Harris SM. Death of a clinician: the personal, practical and clinical implications of therapist mortality. Contemp Fam Ther. 2012;34(3):313-321.

38. Hovey JK. Mortality practices: how clinical social workers interact with their mortality within their clinical and professional practice. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.Paper 1081. http://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=theses. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

39. Frankel AS, Alban A. Professional wills: protecting patients, family members and colleagues. The Steve Frankel Group. https://www.sfrankelgroup.com/professional-wills.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

1. LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, et al. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(6):445-454.

2. Dellinger EP, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):967-971.

3. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G. The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):233-239.

5. Merenstein B, Merenstein J. Patient reflections: saying good-bye to a retiring family doctor. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):461-465.

6. Lord R, Ritvo S, Solnit AJ. Patients’ reactions to the death of the psychoanalyst. Intern J Psychoanal. 1978;59(2-3):189-197.

7. Power A. Forced endings in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: attachment and loss in retirement. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

8. Robutti A. When the patient loses his/her analyst. Italian Psychoanalytic Annual. 2010;4:129-145.

9. Traesdal T. When the analyst dies: dealing with the aftermath. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53(4):1235-1255.

10. Deutsch RA. A voice lost, a voice found: after the death of the analyst. In: Deutsch RA, ed. Traumatic ruptures: abandonment and betrayal in the analytic relationship. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:32-45.

11. Ward VP. On Yoda, trouble, and transformation: the cultural context of therapy and supervision. Contemp Fam Ther. 2009;31(3):171-176.

12. Moffic HS. Mental bootcamp: today is the first day of your retirement! Psychiatr Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/blogs/couch-crisis/mental-bootcamp-today-first-day-your-retirement. Published June 25, 2012. Accessed October 31, 2017.

13. Shatsky P. Everything ends: identity and the therapist’s retirement. Clin Soc Work J. 2016;44(2):143-149.

14. Collier R.

15. Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, et al. Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):794-801.

16. Silver MP. Critical reflection on physician retirement. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):783-784.

17. Clemens NA. A psychiatrist retires: an oxymoron? J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(5):351-354.

18. Packard FR. The earliest hospitals. In: Packard FR. History of medicine in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1901:348.

19. Galatzer-Levy RM. The death of the analyst: patients whose previous analyst died while they were in treatment. J Amer Psychoanalytic Assoc. 2004;52(4):999-1024.

20. Fajardo B. Life-threatening illness in the analyst. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2001;49(2):569-586.

21. Dewald PA. Serious illness in the analyst: transference, countertransference, and reality responses. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1982;30(2):347-363.

22. Howe E. Should psychiatrists self disclose? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(12):14-17.

23. Rizq R, Voller D. ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ On the death of a psychoanalyst. Psychodyn Pract. 2013;19(2):143-167.

24. Babitsky S, Mangraviti JJ. The biggest legal mistakes physicians make—and how to avoid them. Falmouth, MA: SEAK, Inc.; 2005.

25. Armon BD, Bayus K. Legal considerations when making a practice change. Chest. 2014;146(1):215-219.

26. American Medical Association. Opinions on patient-physician relationships: 1.1.5 terminating a patient-physician relationship. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 29, 2017.

27. Lee v Dewbre, 362 S.W. 2d 900 (Tex Civ App 7th Dist 1962).

28. Medical Association of Georgia. Issues for the retiring physician. https://www.mag.org/georgia/uploadedfiles/issues-retiring-physicians.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2017.

29. Massachusetts Medical Society. Issues for the retiring physician. http://www.massmed.org/physicians/practice-management/practice-ownership-and-operations/issues-for-the-retiring-physician-(pdf). Published 2012. Accessed October 1, 2017.

30. North Carolina Medical Board. The doctor is out: a physician’s guide to closing a practice. https://www.ncmedboard.org/images/uploads/article_images/Physicians_Guide_to_Closing_a_Practice_05_12_2014.pdf. Published May 12, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

31. 243 Code of Mass. Regulations §2.06(4)(a).

32. Sampson K. Physician’s guide to closing a practice. Maine Medical Association. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/Closing%20Practice%20Guide%20FINAL%206.2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

33. HealthIT.gov. State medical record laws: minimum medical record retention periods for records held by medical doctors and hospitals. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/appa7-1.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2017.

34. 45 CFR §164.316(b)(2).

35. 42 CFR §422.504(d)(2)(iii).

36. Pope KS, Vasquez MJT. How to survive and thrive as a therapist: information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

37. Becher EH, Ogasawara T, Harris SM. Death of a clinician: the personal, practical and clinical implications of therapist mortality. Contemp Fam Ther. 2012;34(3):313-321.

38. Hovey JK. Mortality practices: how clinical social workers interact with their mortality within their clinical and professional practice. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.Paper 1081. http://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=theses. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

39. Frankel AS, Alban A. Professional wills: protecting patients, family members and colleagues. The Steve Frankel Group. https://www.sfrankelgroup.com/professional-wills.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

Considering work as an expert witness? Look before you leap!

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

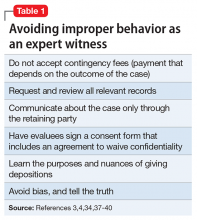

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

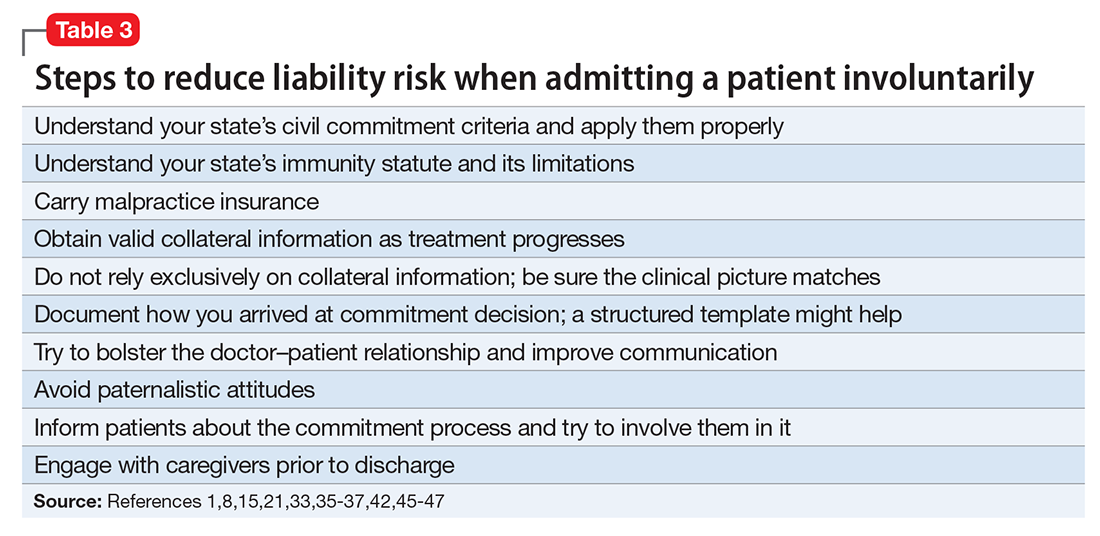

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

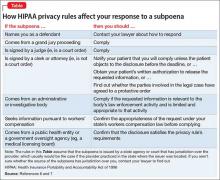

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself