User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Psychiatrists should not reveal what their patients say except to avert a threat to health or safety or to report abuse. So, how can psychiatrists be subpoenaed to provide information for a trial? If I receive a subpoena, how can I comply without violating patient privacy? If I have to go to court, can I “plead the Fifth”?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Physicians who are served with a subpoena feel upset for the reason Dr. S described: Complying with a subpoena seems to violate the obligation to protect patients’ privacy. But physicians can’t “plead the Fifth” under these circumstances, because the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only bars forcing someone to give self-incriminating testimony.1

If you receive a subpoena for information gleaned during patient care, you should not ignore it. Failing to respond might place you in contempt of court and subject you to a fine or even jail time. Yet simply complying could have legal and professional implications, too.

Often, a psychiatrist who receives a subpoena should seek an attorney’s advice on how to best respond. But understanding what subpoenas are and how they work might let you feel less anxious as you go through the process of responding. With this goal in mind, this article covers:

• what a subpoena is and isn’t

• 2 types of privacy obligations

• legal options

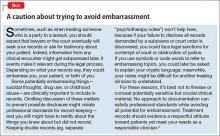

• avoiding potential embarrassment (Box).2

What is a subpoena?

All citizens have a legal obligation to furnish courts with the information needed to decide legal issues.3 Statutes and legal rules dictate how such material comes to court.

Issuing a subpoena (from the Latin sub poena, “under penalty”) is one way of obtaining information needed for a legal proceeding. A subpoena ad testificandum directs the recipient to appear at a legal proceeding and provide testimony. A subpoena duces tecum (“you shall bring with you”) directs the recipient to produce specific records or to appear at a legal proceeding with the records.

Usually, subpoenas are issued by attorneys or court clerks, not by judges. As such, they are not court orders. If you receive a subpoena, you should make a timely response of some sort. But, ultimately, you might not have to release the information. Although physicians have to follow the same rules as other citizens, courts recognize that doctors also have professional obligations to their patients.

Confidentiality: Your reason to hesitate

Receiving a subpoena doesn’t change your obligation to protect your patient’s confidentiality. From the law’s standpoint, patient confidentiality is a function of the rules that govern use of information in legal proceedings.

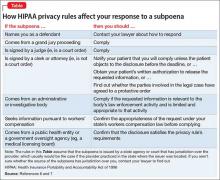

The Privacy Rule4 that arose from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 19965 provides guidance on acceptable responses to subpoenas by “covered entities,” which includes most physicians’ practices. HIPAA permits disclosure of the minimum amount of personal information needed to fulfill the demands of a subpoena. The Table6,7 explains HIPAA’s rules about specific responses to subpoenas, depending on their source.

Many states have patient privacy laws that are stricter than HIPAA rules. If you practice in one of those states, you have to follow the more stringent rule.8 For example, Ohio law does not let subpoenaed providers tender medical records for use in a grand jury proceeding without a release signed by the patient, although HIPAA would allow this (Table).6,7 Out of concern that “giving law enforcement unbridled access to medical records could discourage patients from seeking medical treatment,” Ohio protects patient records more than HIPAA does.9 New York State’s privilege rules also are stricter than HIPAA10 and contain specific provisions about releasing certain types of information (eg, HIV status11). State courts expect physicians to follow their laws about patient privacy and to consult attorneys to make sure that releasing information is done properly.12

Releasing information improperly could become grounds for legal action against you, even if you released the information in response to a subpoena. Legal action could take the form of a lawsuit for breach of confidentiality, a HIPAA-based complaint, a complaint to the state medical board, or all 3 of these.

Must you turn over information?

Before you testify or turn over documents, you need to verify that the legal and ethical requirements for the disclosure are met—as you would for any release of patient information. You can do this by obtaining your patient’s formal, written consent for the disclosure. Before you accept the patient’s agreement, however, you might—and in most cases should— consider discussing how the disclosure could affect the patient’s well-being or your treatment relationship.

If the patient will not agree to the disclosure, the patient or the patient’s attorney can seek to have the subpoena modified or quashed (declared void). One tactic for doing this is by asserting doctor–patient privilege, a legal doctrine codified in most state’s laws. The privilege recognizes that, because privacy is important in medical care, stopping clinical information from automatically coming in court serves an important social purpose.13

The doctor–patient privilege belongs to the litigant—here, your patient—not to you, so your patient has to raise the objection to releasing information.14 Also, the privilege is not absolute. If having the clinical information is necessary, the judge may issue a court order denying the patient’s motion to quash. Unless the judge later modifies or vacates the order, you risk being found in contempt of court if you still refuse to turn over documents demanded by the subpoena.

Fact witness or expert witness?

If the subpoena demands your testimony, the issuing party might want you to serve as a fact witness or expert witness. Persons with relevant personal knowledge to a legal proceeding can serve as fact witnesses, and testify about things they did or perceived.15 For example, a psychiatrist serving as a fact witness could recount having heard or seen a patient talking aloud as if arguing with someone when no real interlocutor was present.

A witness whom the court deems an “expert” by virtue of special knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may offer opinions based on specific sets of facts. Courts hear such testimony when the expert’s specialized knowledge will help the jury understand the evidence or reach a verdict in a case.16 To return to the example above: a psychiatric expert witness might tell jurors that the patient’s “arguing” was evidence that she was hallucinating and suffered from schizophrenia.

If you receive a subpoena to testify about someone you have treated, you should notify the issuing party that you will provide fact testimony if required to do so. You cannot be compelled to serve as an expert witness, however. In many situations, attempting to provide objective expert testimony about one’s own patient could create unresolvable conflicts between the obligation to tell the truth and your obligation to serve your patient’s interests.17

If the subpoena requests deposition testimony about a patient, you probably will be able to schedule the deposition at a time that is convenient for you and the attorneys involved. Yet you should not agree to be deposed unless (a) you have received the patient’s authorization, (b) a court has ordered you to testify despite the patient’s objection, or (c) your attorney (whom you have consulted about the situation) has advised you that providing testimony is appropriate.

If you are called as a fact witness for a trial, the attorney or court that has subpoenaed you often will try to schedule things to minimize the time taken away from your other duties. Once in court, you can ask the judge (on the record) whether you must answer if you are asked questions about a patient who has not previously authorized you to release treatment information. A judge’s explicit command to respond absolves you of any further ethical obligation to withhold confidential information about the patient’s care.

Bottom Line

If you receive a subpoena for records or testimony, obtaining the patient’s written authorization should allow you to release the information without violating confidentiality obligations. If your patient won’t agree to the release, if turning over information might adversely affect the patient, or if you’re not sure what to do, seek advice from an attorney who knows about medical privacy rules. That way, you can be sure you are meeting all legal and professional standards that apply.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with any manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kastigar v United States, 406 US 441 (1972).

2. Barsky AE. Clinicians in court, second edition: A guide to subpoenas, depositions, testifying, and everything else you need to know. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

3. United States v Bryan, 339 US 323 (1950).

4. 45 CFR §164.50.

5. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164.

6. 45 CFR §164.512.

7. Stanger K. HIPAA: responding to subpoenas, orders, and administrative demands. http://www.hhhealthlawblog.com/2013/10/hipaa-responding-to-subpoenas-orders-and-administrative-demands.html. Published October 9, 2013. Accessed September 22, 2015.

8. Zwerling AL, de Harder WA, Tarpey CM. To disclose or not to disclose, that is the question: issues to consider before responding to a subpoena. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9(4):279-281.

9. Turk v Oilier, 732 F Supp 2d 758 (ND Ohio 2010).

10. In re Antonia E, 16 Misc 3d 637 (Fam Ct Queens County 2007).

11. NY PBH Law §2785.

12. Crescenzo v Crane, 796 A2d 283 (NJ Super Ct App Div 2002).

13. In re Bruendl’s Will, 102 Wis 45, 78 NW 169 (1899).

14. In re Lifschutz, 2 Cal 3d 415, 85 Cal Rptr 829, 467 P2d 557 (1970).

15. Broun KS, Dix GE, Imwinkelried EJ, et al. McCormick on evidence. 7th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2013.

16. Fed Evid R 702.

17. Strasburger LH, Gutheil TG, Brodsky A. On wearing two hats: role conflict in serving as both psychotherapist and expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:448-456.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Psychiatrists should not reveal what their patients say except to avert a threat to health or safety or to report abuse. So, how can psychiatrists be subpoenaed to provide information for a trial? If I receive a subpoena, how can I comply without violating patient privacy? If I have to go to court, can I “plead the Fifth”?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Physicians who are served with a subpoena feel upset for the reason Dr. S described: Complying with a subpoena seems to violate the obligation to protect patients’ privacy. But physicians can’t “plead the Fifth” under these circumstances, because the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only bars forcing someone to give self-incriminating testimony.1

If you receive a subpoena for information gleaned during patient care, you should not ignore it. Failing to respond might place you in contempt of court and subject you to a fine or even jail time. Yet simply complying could have legal and professional implications, too.

Often, a psychiatrist who receives a subpoena should seek an attorney’s advice on how to best respond. But understanding what subpoenas are and how they work might let you feel less anxious as you go through the process of responding. With this goal in mind, this article covers:

• what a subpoena is and isn’t

• 2 types of privacy obligations

• legal options

• avoiding potential embarrassment (Box).2

What is a subpoena?

All citizens have a legal obligation to furnish courts with the information needed to decide legal issues.3 Statutes and legal rules dictate how such material comes to court.

Issuing a subpoena (from the Latin sub poena, “under penalty”) is one way of obtaining information needed for a legal proceeding. A subpoena ad testificandum directs the recipient to appear at a legal proceeding and provide testimony. A subpoena duces tecum (“you shall bring with you”) directs the recipient to produce specific records or to appear at a legal proceeding with the records.

Usually, subpoenas are issued by attorneys or court clerks, not by judges. As such, they are not court orders. If you receive a subpoena, you should make a timely response of some sort. But, ultimately, you might not have to release the information. Although physicians have to follow the same rules as other citizens, courts recognize that doctors also have professional obligations to their patients.

Confidentiality: Your reason to hesitate

Receiving a subpoena doesn’t change your obligation to protect your patient’s confidentiality. From the law’s standpoint, patient confidentiality is a function of the rules that govern use of information in legal proceedings.

The Privacy Rule4 that arose from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 19965 provides guidance on acceptable responses to subpoenas by “covered entities,” which includes most physicians’ practices. HIPAA permits disclosure of the minimum amount of personal information needed to fulfill the demands of a subpoena. The Table6,7 explains HIPAA’s rules about specific responses to subpoenas, depending on their source.

Many states have patient privacy laws that are stricter than HIPAA rules. If you practice in one of those states, you have to follow the more stringent rule.8 For example, Ohio law does not let subpoenaed providers tender medical records for use in a grand jury proceeding without a release signed by the patient, although HIPAA would allow this (Table).6,7 Out of concern that “giving law enforcement unbridled access to medical records could discourage patients from seeking medical treatment,” Ohio protects patient records more than HIPAA does.9 New York State’s privilege rules also are stricter than HIPAA10 and contain specific provisions about releasing certain types of information (eg, HIV status11). State courts expect physicians to follow their laws about patient privacy and to consult attorneys to make sure that releasing information is done properly.12

Releasing information improperly could become grounds for legal action against you, even if you released the information in response to a subpoena. Legal action could take the form of a lawsuit for breach of confidentiality, a HIPAA-based complaint, a complaint to the state medical board, or all 3 of these.

Must you turn over information?

Before you testify or turn over documents, you need to verify that the legal and ethical requirements for the disclosure are met—as you would for any release of patient information. You can do this by obtaining your patient’s formal, written consent for the disclosure. Before you accept the patient’s agreement, however, you might—and in most cases should— consider discussing how the disclosure could affect the patient’s well-being or your treatment relationship.

If the patient will not agree to the disclosure, the patient or the patient’s attorney can seek to have the subpoena modified or quashed (declared void). One tactic for doing this is by asserting doctor–patient privilege, a legal doctrine codified in most state’s laws. The privilege recognizes that, because privacy is important in medical care, stopping clinical information from automatically coming in court serves an important social purpose.13

The doctor–patient privilege belongs to the litigant—here, your patient—not to you, so your patient has to raise the objection to releasing information.14 Also, the privilege is not absolute. If having the clinical information is necessary, the judge may issue a court order denying the patient’s motion to quash. Unless the judge later modifies or vacates the order, you risk being found in contempt of court if you still refuse to turn over documents demanded by the subpoena.

Fact witness or expert witness?

If the subpoena demands your testimony, the issuing party might want you to serve as a fact witness or expert witness. Persons with relevant personal knowledge to a legal proceeding can serve as fact witnesses, and testify about things they did or perceived.15 For example, a psychiatrist serving as a fact witness could recount having heard or seen a patient talking aloud as if arguing with someone when no real interlocutor was present.

A witness whom the court deems an “expert” by virtue of special knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may offer opinions based on specific sets of facts. Courts hear such testimony when the expert’s specialized knowledge will help the jury understand the evidence or reach a verdict in a case.16 To return to the example above: a psychiatric expert witness might tell jurors that the patient’s “arguing” was evidence that she was hallucinating and suffered from schizophrenia.

If you receive a subpoena to testify about someone you have treated, you should notify the issuing party that you will provide fact testimony if required to do so. You cannot be compelled to serve as an expert witness, however. In many situations, attempting to provide objective expert testimony about one’s own patient could create unresolvable conflicts between the obligation to tell the truth and your obligation to serve your patient’s interests.17

If the subpoena requests deposition testimony about a patient, you probably will be able to schedule the deposition at a time that is convenient for you and the attorneys involved. Yet you should not agree to be deposed unless (a) you have received the patient’s authorization, (b) a court has ordered you to testify despite the patient’s objection, or (c) your attorney (whom you have consulted about the situation) has advised you that providing testimony is appropriate.

If you are called as a fact witness for a trial, the attorney or court that has subpoenaed you often will try to schedule things to minimize the time taken away from your other duties. Once in court, you can ask the judge (on the record) whether you must answer if you are asked questions about a patient who has not previously authorized you to release treatment information. A judge’s explicit command to respond absolves you of any further ethical obligation to withhold confidential information about the patient’s care.

Bottom Line

If you receive a subpoena for records or testimony, obtaining the patient’s written authorization should allow you to release the information without violating confidentiality obligations. If your patient won’t agree to the release, if turning over information might adversely affect the patient, or if you’re not sure what to do, seek advice from an attorney who knows about medical privacy rules. That way, you can be sure you are meeting all legal and professional standards that apply.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with any manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Psychiatrists should not reveal what their patients say except to avert a threat to health or safety or to report abuse. So, how can psychiatrists be subpoenaed to provide information for a trial? If I receive a subpoena, how can I comply without violating patient privacy? If I have to go to court, can I “plead the Fifth”?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Physicians who are served with a subpoena feel upset for the reason Dr. S described: Complying with a subpoena seems to violate the obligation to protect patients’ privacy. But physicians can’t “plead the Fifth” under these circumstances, because the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only bars forcing someone to give self-incriminating testimony.1

If you receive a subpoena for information gleaned during patient care, you should not ignore it. Failing to respond might place you in contempt of court and subject you to a fine or even jail time. Yet simply complying could have legal and professional implications, too.

Often, a psychiatrist who receives a subpoena should seek an attorney’s advice on how to best respond. But understanding what subpoenas are and how they work might let you feel less anxious as you go through the process of responding. With this goal in mind, this article covers:

• what a subpoena is and isn’t

• 2 types of privacy obligations

• legal options

• avoiding potential embarrassment (Box).2

What is a subpoena?

All citizens have a legal obligation to furnish courts with the information needed to decide legal issues.3 Statutes and legal rules dictate how such material comes to court.

Issuing a subpoena (from the Latin sub poena, “under penalty”) is one way of obtaining information needed for a legal proceeding. A subpoena ad testificandum directs the recipient to appear at a legal proceeding and provide testimony. A subpoena duces tecum (“you shall bring with you”) directs the recipient to produce specific records or to appear at a legal proceeding with the records.

Usually, subpoenas are issued by attorneys or court clerks, not by judges. As such, they are not court orders. If you receive a subpoena, you should make a timely response of some sort. But, ultimately, you might not have to release the information. Although physicians have to follow the same rules as other citizens, courts recognize that doctors also have professional obligations to their patients.

Confidentiality: Your reason to hesitate

Receiving a subpoena doesn’t change your obligation to protect your patient’s confidentiality. From the law’s standpoint, patient confidentiality is a function of the rules that govern use of information in legal proceedings.

The Privacy Rule4 that arose from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 19965 provides guidance on acceptable responses to subpoenas by “covered entities,” which includes most physicians’ practices. HIPAA permits disclosure of the minimum amount of personal information needed to fulfill the demands of a subpoena. The Table6,7 explains HIPAA’s rules about specific responses to subpoenas, depending on their source.

Many states have patient privacy laws that are stricter than HIPAA rules. If you practice in one of those states, you have to follow the more stringent rule.8 For example, Ohio law does not let subpoenaed providers tender medical records for use in a grand jury proceeding without a release signed by the patient, although HIPAA would allow this (Table).6,7 Out of concern that “giving law enforcement unbridled access to medical records could discourage patients from seeking medical treatment,” Ohio protects patient records more than HIPAA does.9 New York State’s privilege rules also are stricter than HIPAA10 and contain specific provisions about releasing certain types of information (eg, HIV status11). State courts expect physicians to follow their laws about patient privacy and to consult attorneys to make sure that releasing information is done properly.12

Releasing information improperly could become grounds for legal action against you, even if you released the information in response to a subpoena. Legal action could take the form of a lawsuit for breach of confidentiality, a HIPAA-based complaint, a complaint to the state medical board, or all 3 of these.

Must you turn over information?

Before you testify or turn over documents, you need to verify that the legal and ethical requirements for the disclosure are met—as you would for any release of patient information. You can do this by obtaining your patient’s formal, written consent for the disclosure. Before you accept the patient’s agreement, however, you might—and in most cases should— consider discussing how the disclosure could affect the patient’s well-being or your treatment relationship.

If the patient will not agree to the disclosure, the patient or the patient’s attorney can seek to have the subpoena modified or quashed (declared void). One tactic for doing this is by asserting doctor–patient privilege, a legal doctrine codified in most state’s laws. The privilege recognizes that, because privacy is important in medical care, stopping clinical information from automatically coming in court serves an important social purpose.13

The doctor–patient privilege belongs to the litigant—here, your patient—not to you, so your patient has to raise the objection to releasing information.14 Also, the privilege is not absolute. If having the clinical information is necessary, the judge may issue a court order denying the patient’s motion to quash. Unless the judge later modifies or vacates the order, you risk being found in contempt of court if you still refuse to turn over documents demanded by the subpoena.

Fact witness or expert witness?

If the subpoena demands your testimony, the issuing party might want you to serve as a fact witness or expert witness. Persons with relevant personal knowledge to a legal proceeding can serve as fact witnesses, and testify about things they did or perceived.15 For example, a psychiatrist serving as a fact witness could recount having heard or seen a patient talking aloud as if arguing with someone when no real interlocutor was present.

A witness whom the court deems an “expert” by virtue of special knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may offer opinions based on specific sets of facts. Courts hear such testimony when the expert’s specialized knowledge will help the jury understand the evidence or reach a verdict in a case.16 To return to the example above: a psychiatric expert witness might tell jurors that the patient’s “arguing” was evidence that she was hallucinating and suffered from schizophrenia.

If you receive a subpoena to testify about someone you have treated, you should notify the issuing party that you will provide fact testimony if required to do so. You cannot be compelled to serve as an expert witness, however. In many situations, attempting to provide objective expert testimony about one’s own patient could create unresolvable conflicts between the obligation to tell the truth and your obligation to serve your patient’s interests.17

If the subpoena requests deposition testimony about a patient, you probably will be able to schedule the deposition at a time that is convenient for you and the attorneys involved. Yet you should not agree to be deposed unless (a) you have received the patient’s authorization, (b) a court has ordered you to testify despite the patient’s objection, or (c) your attorney (whom you have consulted about the situation) has advised you that providing testimony is appropriate.

If you are called as a fact witness for a trial, the attorney or court that has subpoenaed you often will try to schedule things to minimize the time taken away from your other duties. Once in court, you can ask the judge (on the record) whether you must answer if you are asked questions about a patient who has not previously authorized you to release treatment information. A judge’s explicit command to respond absolves you of any further ethical obligation to withhold confidential information about the patient’s care.

Bottom Line

If you receive a subpoena for records or testimony, obtaining the patient’s written authorization should allow you to release the information without violating confidentiality obligations. If your patient won’t agree to the release, if turning over information might adversely affect the patient, or if you’re not sure what to do, seek advice from an attorney who knows about medical privacy rules. That way, you can be sure you are meeting all legal and professional standards that apply.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with any manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kastigar v United States, 406 US 441 (1972).

2. Barsky AE. Clinicians in court, second edition: A guide to subpoenas, depositions, testifying, and everything else you need to know. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

3. United States v Bryan, 339 US 323 (1950).

4. 45 CFR §164.50.

5. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164.

6. 45 CFR §164.512.

7. Stanger K. HIPAA: responding to subpoenas, orders, and administrative demands. http://www.hhhealthlawblog.com/2013/10/hipaa-responding-to-subpoenas-orders-and-administrative-demands.html. Published October 9, 2013. Accessed September 22, 2015.

8. Zwerling AL, de Harder WA, Tarpey CM. To disclose or not to disclose, that is the question: issues to consider before responding to a subpoena. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9(4):279-281.

9. Turk v Oilier, 732 F Supp 2d 758 (ND Ohio 2010).

10. In re Antonia E, 16 Misc 3d 637 (Fam Ct Queens County 2007).

11. NY PBH Law §2785.

12. Crescenzo v Crane, 796 A2d 283 (NJ Super Ct App Div 2002).

13. In re Bruendl’s Will, 102 Wis 45, 78 NW 169 (1899).

14. In re Lifschutz, 2 Cal 3d 415, 85 Cal Rptr 829, 467 P2d 557 (1970).

15. Broun KS, Dix GE, Imwinkelried EJ, et al. McCormick on evidence. 7th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2013.

16. Fed Evid R 702.

17. Strasburger LH, Gutheil TG, Brodsky A. On wearing two hats: role conflict in serving as both psychotherapist and expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:448-456.

1. Kastigar v United States, 406 US 441 (1972).

2. Barsky AE. Clinicians in court, second edition: A guide to subpoenas, depositions, testifying, and everything else you need to know. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

3. United States v Bryan, 339 US 323 (1950).

4. 45 CFR §164.50.

5. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164.

6. 45 CFR §164.512.

7. Stanger K. HIPAA: responding to subpoenas, orders, and administrative demands. http://www.hhhealthlawblog.com/2013/10/hipaa-responding-to-subpoenas-orders-and-administrative-demands.html. Published October 9, 2013. Accessed September 22, 2015.

8. Zwerling AL, de Harder WA, Tarpey CM. To disclose or not to disclose, that is the question: issues to consider before responding to a subpoena. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9(4):279-281.

9. Turk v Oilier, 732 F Supp 2d 758 (ND Ohio 2010).

10. In re Antonia E, 16 Misc 3d 637 (Fam Ct Queens County 2007).

11. NY PBH Law §2785.

12. Crescenzo v Crane, 796 A2d 283 (NJ Super Ct App Div 2002).

13. In re Bruendl’s Will, 102 Wis 45, 78 NW 169 (1899).

14. In re Lifschutz, 2 Cal 3d 415, 85 Cal Rptr 829, 467 P2d 557 (1970).

15. Broun KS, Dix GE, Imwinkelried EJ, et al. McCormick on evidence. 7th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2013.

16. Fed Evid R 702.

17. Strasburger LH, Gutheil TG, Brodsky A. On wearing two hats: role conflict in serving as both psychotherapist and expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:448-456.