User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27

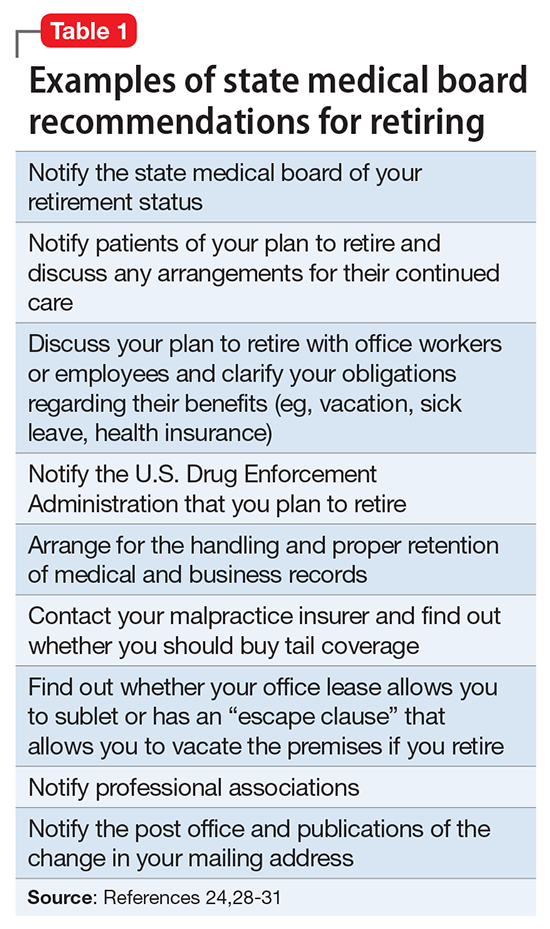

Further obligations come from medical licensing boards, which, in many states, have established time frames and specific procedures for informing patients and the public when a physician is leaving practice. Table 124,28-31 lists examples of these. If Dr. F works in a state where the board hasn’t promulgated such regulations, Table 124,28-31 may still help him think through how to discharge his ethical responsibilities to notify patients, colleagues, and business entities that he is ending his practice. References 28-30 and 32 discuss several of these matters, suggest timetables for various steps of a practice closure, and provide sample letters for notifying patients.

Physicians also must preserve their medical records for a certain period after they retire. States with rules on this matter require record preservation for 5 to 10 years or until 2 or 3 years after minor patients reach the age of majority.33 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 requires covered entities, which include most psychiatrists, to retain records for 6 years,34 and certain Medicare programs require retention for 10 years.35

Depending on Dr. F’s location and type of practice, his records should be preserved for the longest period that applies. If he is leaving a group practice that owns the records, arranging for this should be easy. If leaving an independent practice, he may need to ask another practice to perform this function.25

A ‘professional will’

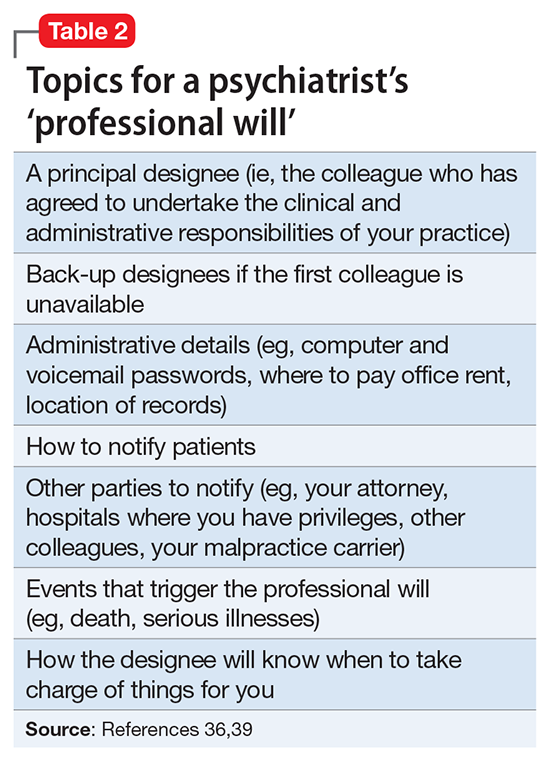

Dr. F also might consider a measure that many psychotherapists recommend13,19,36 and that in some states is required by mental health licensing boards or professional codes37,38: creating a “professional will” that contains instructions for handling practice matters in case of death or disability.39

1. LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, et al. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(6):445-454.

2. Dellinger EP, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):967-971.

3. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G. The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):233-239.

5. Merenstein B, Merenstein J. Patient reflections: saying good-bye to a retiring family doctor. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):461-465.

6. Lord R, Ritvo S, Solnit AJ. Patients’ reactions to the death of the psychoanalyst. Intern J Psychoanal. 1978;59(2-3):189-197.

7. Power A. Forced endings in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: attachment and loss in retirement. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

8. Robutti A. When the patient loses his/her analyst. Italian Psychoanalytic Annual. 2010;4:129-145.

9. Traesdal T. When the analyst dies: dealing with the aftermath. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53(4):1235-1255.

10. Deutsch RA. A voice lost, a voice found: after the death of the analyst. In: Deutsch RA, ed. Traumatic ruptures: abandonment and betrayal in the analytic relationship. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:32-45.

11. Ward VP. On Yoda, trouble, and transformation: the cultural context of therapy and supervision. Contemp Fam Ther. 2009;31(3):171-176.

12. Moffic HS. Mental bootcamp: today is the first day of your retirement! Psychiatr Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/blogs/couch-crisis/mental-bootcamp-today-first-day-your-retirement. Published June 25, 2012. Accessed October 31, 2017.

13. Shatsky P. Everything ends: identity and the therapist’s retirement. Clin Soc Work J. 2016;44(2):143-149.

14. Collier R.

15. Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, et al. Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):794-801.

16. Silver MP. Critical reflection on physician retirement. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):783-784.

17. Clemens NA. A psychiatrist retires: an oxymoron? J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(5):351-354.

18. Packard FR. The earliest hospitals. In: Packard FR. History of medicine in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1901:348.

19. Galatzer-Levy RM. The death of the analyst: patients whose previous analyst died while they were in treatment. J Amer Psychoanalytic Assoc. 2004;52(4):999-1024.

20. Fajardo B. Life-threatening illness in the analyst. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2001;49(2):569-586.

21. Dewald PA. Serious illness in the analyst: transference, countertransference, and reality responses. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1982;30(2):347-363.

22. Howe E. Should psychiatrists self disclose? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(12):14-17.

23. Rizq R, Voller D. ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ On the death of a psychoanalyst. Psychodyn Pract. 2013;19(2):143-167.

24. Babitsky S, Mangraviti JJ. The biggest legal mistakes physicians make—and how to avoid them. Falmouth, MA: SEAK, Inc.; 2005.

25. Armon BD, Bayus K. Legal considerations when making a practice change. Chest. 2014;146(1):215-219.

26. American Medical Association. Opinions on patient-physician relationships: 1.1.5 terminating a patient-physician relationship. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 29, 2017.

27. Lee v Dewbre, 362 S.W. 2d 900 (Tex Civ App 7th Dist 1962).

28. Medical Association of Georgia. Issues for the retiring physician. https://www.mag.org/georgia/uploadedfiles/issues-retiring-physicians.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2017.

29. Massachusetts Medical Society. Issues for the retiring physician. http://www.massmed.org/physicians/practice-management/practice-ownership-and-operations/issues-for-the-retiring-physician-(pdf). Published 2012. Accessed October 1, 2017.

30. North Carolina Medical Board. The doctor is out: a physician’s guide to closing a practice. https://www.ncmedboard.org/images/uploads/article_images/Physicians_Guide_to_Closing_a_Practice_05_12_2014.pdf. Published May 12, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

31. 243 Code of Mass. Regulations §2.06(4)(a).

32. Sampson K. Physician’s guide to closing a practice. Maine Medical Association. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/Closing%20Practice%20Guide%20FINAL%206.2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

33. HealthIT.gov. State medical record laws: minimum medical record retention periods for records held by medical doctors and hospitals. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/appa7-1.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2017.

34. 45 CFR §164.316(b)(2).

35. 42 CFR §422.504(d)(2)(iii).

36. Pope KS, Vasquez MJT. How to survive and thrive as a therapist: information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

37. Becher EH, Ogasawara T, Harris SM. Death of a clinician: the personal, practical and clinical implications of therapist mortality. Contemp Fam Ther. 2012;34(3):313-321.

38. Hovey JK. Mortality practices: how clinical social workers interact with their mortality within their clinical and professional practice. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.Paper 1081. http://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=theses. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

39. Frankel AS, Alban A. Professional wills: protecting patients, family members and colleagues. The Steve Frankel Group. https://www.sfrankelgroup.com/professional-wills.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27

Further obligations come from medical licensing boards, which, in many states, have established time frames and specific procedures for informing patients and the public when a physician is leaving practice. Table 124,28-31 lists examples of these. If Dr. F works in a state where the board hasn’t promulgated such regulations, Table 124,28-31 may still help him think through how to discharge his ethical responsibilities to notify patients, colleagues, and business entities that he is ending his practice. References 28-30 and 32 discuss several of these matters, suggest timetables for various steps of a practice closure, and provide sample letters for notifying patients.

Physicians also must preserve their medical records for a certain period after they retire. States with rules on this matter require record preservation for 5 to 10 years or until 2 or 3 years after minor patients reach the age of majority.33 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 requires covered entities, which include most psychiatrists, to retain records for 6 years,34 and certain Medicare programs require retention for 10 years.35

Depending on Dr. F’s location and type of practice, his records should be preserved for the longest period that applies. If he is leaving a group practice that owns the records, arranging for this should be easy. If leaving an independent practice, he may need to ask another practice to perform this function.25

A ‘professional will’

Dr. F also might consider a measure that many psychotherapists recommend13,19,36 and that in some states is required by mental health licensing boards or professional codes37,38: creating a “professional will” that contains instructions for handling practice matters in case of death or disability.39

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27

Further obligations come from medical licensing boards, which, in many states, have established time frames and specific procedures for informing patients and the public when a physician is leaving practice. Table 124,28-31 lists examples of these. If Dr. F works in a state where the board hasn’t promulgated such regulations, Table 124,28-31 may still help him think through how to discharge his ethical responsibilities to notify patients, colleagues, and business entities that he is ending his practice. References 28-30 and 32 discuss several of these matters, suggest timetables for various steps of a practice closure, and provide sample letters for notifying patients.

Physicians also must preserve their medical records for a certain period after they retire. States with rules on this matter require record preservation for 5 to 10 years or until 2 or 3 years after minor patients reach the age of majority.33 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 requires covered entities, which include most psychiatrists, to retain records for 6 years,34 and certain Medicare programs require retention for 10 years.35

Depending on Dr. F’s location and type of practice, his records should be preserved for the longest period that applies. If he is leaving a group practice that owns the records, arranging for this should be easy. If leaving an independent practice, he may need to ask another practice to perform this function.25

A ‘professional will’

Dr. F also might consider a measure that many psychotherapists recommend13,19,36 and that in some states is required by mental health licensing boards or professional codes37,38: creating a “professional will” that contains instructions for handling practice matters in case of death or disability.39

1. LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, et al. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(6):445-454.

2. Dellinger EP, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):967-971.

3. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G. The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):233-239.

5. Merenstein B, Merenstein J. Patient reflections: saying good-bye to a retiring family doctor. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):461-465.

6. Lord R, Ritvo S, Solnit AJ. Patients’ reactions to the death of the psychoanalyst. Intern J Psychoanal. 1978;59(2-3):189-197.

7. Power A. Forced endings in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: attachment and loss in retirement. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

8. Robutti A. When the patient loses his/her analyst. Italian Psychoanalytic Annual. 2010;4:129-145.

9. Traesdal T. When the analyst dies: dealing with the aftermath. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53(4):1235-1255.

10. Deutsch RA. A voice lost, a voice found: after the death of the analyst. In: Deutsch RA, ed. Traumatic ruptures: abandonment and betrayal in the analytic relationship. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:32-45.

11. Ward VP. On Yoda, trouble, and transformation: the cultural context of therapy and supervision. Contemp Fam Ther. 2009;31(3):171-176.

12. Moffic HS. Mental bootcamp: today is the first day of your retirement! Psychiatr Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/blogs/couch-crisis/mental-bootcamp-today-first-day-your-retirement. Published June 25, 2012. Accessed October 31, 2017.

13. Shatsky P. Everything ends: identity and the therapist’s retirement. Clin Soc Work J. 2016;44(2):143-149.

14. Collier R.

15. Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, et al. Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):794-801.

16. Silver MP. Critical reflection on physician retirement. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):783-784.

17. Clemens NA. A psychiatrist retires: an oxymoron? J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(5):351-354.

18. Packard FR. The earliest hospitals. In: Packard FR. History of medicine in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1901:348.

19. Galatzer-Levy RM. The death of the analyst: patients whose previous analyst died while they were in treatment. J Amer Psychoanalytic Assoc. 2004;52(4):999-1024.

20. Fajardo B. Life-threatening illness in the analyst. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2001;49(2):569-586.

21. Dewald PA. Serious illness in the analyst: transference, countertransference, and reality responses. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1982;30(2):347-363.

22. Howe E. Should psychiatrists self disclose? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(12):14-17.

23. Rizq R, Voller D. ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ On the death of a psychoanalyst. Psychodyn Pract. 2013;19(2):143-167.

24. Babitsky S, Mangraviti JJ. The biggest legal mistakes physicians make—and how to avoid them. Falmouth, MA: SEAK, Inc.; 2005.

25. Armon BD, Bayus K. Legal considerations when making a practice change. Chest. 2014;146(1):215-219.

26. American Medical Association. Opinions on patient-physician relationships: 1.1.5 terminating a patient-physician relationship. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 29, 2017.

27. Lee v Dewbre, 362 S.W. 2d 900 (Tex Civ App 7th Dist 1962).

28. Medical Association of Georgia. Issues for the retiring physician. https://www.mag.org/georgia/uploadedfiles/issues-retiring-physicians.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2017.

29. Massachusetts Medical Society. Issues for the retiring physician. http://www.massmed.org/physicians/practice-management/practice-ownership-and-operations/issues-for-the-retiring-physician-(pdf). Published 2012. Accessed October 1, 2017.

30. North Carolina Medical Board. The doctor is out: a physician’s guide to closing a practice. https://www.ncmedboard.org/images/uploads/article_images/Physicians_Guide_to_Closing_a_Practice_05_12_2014.pdf. Published May 12, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

31. 243 Code of Mass. Regulations §2.06(4)(a).

32. Sampson K. Physician’s guide to closing a practice. Maine Medical Association. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/Closing%20Practice%20Guide%20FINAL%206.2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

33. HealthIT.gov. State medical record laws: minimum medical record retention periods for records held by medical doctors and hospitals. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/appa7-1.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2017.

34. 45 CFR §164.316(b)(2).

35. 42 CFR §422.504(d)(2)(iii).

36. Pope KS, Vasquez MJT. How to survive and thrive as a therapist: information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

37. Becher EH, Ogasawara T, Harris SM. Death of a clinician: the personal, practical and clinical implications of therapist mortality. Contemp Fam Ther. 2012;34(3):313-321.

38. Hovey JK. Mortality practices: how clinical social workers interact with their mortality within their clinical and professional practice. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.Paper 1081. http://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=theses. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

39. Frankel AS, Alban A. Professional wills: protecting patients, family members and colleagues. The Steve Frankel Group. https://www.sfrankelgroup.com/professional-wills.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

1. LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, et al. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(6):445-454.

2. Dellinger EP, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(10):967-971.

3. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G. The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):233-239.

5. Merenstein B, Merenstein J. Patient reflections: saying good-bye to a retiring family doctor. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):461-465.

6. Lord R, Ritvo S, Solnit AJ. Patients’ reactions to the death of the psychoanalyst. Intern J Psychoanal. 1978;59(2-3):189-197.

7. Power A. Forced endings in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: attachment and loss in retirement. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

8. Robutti A. When the patient loses his/her analyst. Italian Psychoanalytic Annual. 2010;4:129-145.

9. Traesdal T. When the analyst dies: dealing with the aftermath. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53(4):1235-1255.

10. Deutsch RA. A voice lost, a voice found: after the death of the analyst. In: Deutsch RA, ed. Traumatic ruptures: abandonment and betrayal in the analytic relationship. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:32-45.

11. Ward VP. On Yoda, trouble, and transformation: the cultural context of therapy and supervision. Contemp Fam Ther. 2009;31(3):171-176.

12. Moffic HS. Mental bootcamp: today is the first day of your retirement! Psychiatr Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/blogs/couch-crisis/mental-bootcamp-today-first-day-your-retirement. Published June 25, 2012. Accessed October 31, 2017.

13. Shatsky P. Everything ends: identity and the therapist’s retirement. Clin Soc Work J. 2016;44(2):143-149.

14. Collier R.

15. Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, et al. Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):794-801.

16. Silver MP. Critical reflection on physician retirement. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):783-784.

17. Clemens NA. A psychiatrist retires: an oxymoron? J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(5):351-354.

18. Packard FR. The earliest hospitals. In: Packard FR. History of medicine in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1901:348.

19. Galatzer-Levy RM. The death of the analyst: patients whose previous analyst died while they were in treatment. J Amer Psychoanalytic Assoc. 2004;52(4):999-1024.

20. Fajardo B. Life-threatening illness in the analyst. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2001;49(2):569-586.

21. Dewald PA. Serious illness in the analyst: transference, countertransference, and reality responses. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1982;30(2):347-363.

22. Howe E. Should psychiatrists self disclose? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(12):14-17.

23. Rizq R, Voller D. ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ On the death of a psychoanalyst. Psychodyn Pract. 2013;19(2):143-167.

24. Babitsky S, Mangraviti JJ. The biggest legal mistakes physicians make—and how to avoid them. Falmouth, MA: SEAK, Inc.; 2005.

25. Armon BD, Bayus K. Legal considerations when making a practice change. Chest. 2014;146(1):215-219.

26. American Medical Association. Opinions on patient-physician relationships: 1.1.5 terminating a patient-physician relationship. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 29, 2017.

27. Lee v Dewbre, 362 S.W. 2d 900 (Tex Civ App 7th Dist 1962).

28. Medical Association of Georgia. Issues for the retiring physician. https://www.mag.org/georgia/uploadedfiles/issues-retiring-physicians.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2017.

29. Massachusetts Medical Society. Issues for the retiring physician. http://www.massmed.org/physicians/practice-management/practice-ownership-and-operations/issues-for-the-retiring-physician-(pdf). Published 2012. Accessed October 1, 2017.

30. North Carolina Medical Board. The doctor is out: a physician’s guide to closing a practice. https://www.ncmedboard.org/images/uploads/article_images/Physicians_Guide_to_Closing_a_Practice_05_12_2014.pdf. Published May 12, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

31. 243 Code of Mass. Regulations §2.06(4)(a).

32. Sampson K. Physician’s guide to closing a practice. Maine Medical Association. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/Closing%20Practice%20Guide%20FINAL%206.2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

33. HealthIT.gov. State medical record laws: minimum medical record retention periods for records held by medical doctors and hospitals. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/appa7-1.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2017.

34. 45 CFR §164.316(b)(2).

35. 42 CFR §422.504(d)(2)(iii).

36. Pope KS, Vasquez MJT. How to survive and thrive as a therapist: information, ideas, and resources for psychologists in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

37. Becher EH, Ogasawara T, Harris SM. Death of a clinician: the personal, practical and clinical implications of therapist mortality. Contemp Fam Ther. 2012;34(3):313-321.

38. Hovey JK. Mortality practices: how clinical social workers interact with their mortality within their clinical and professional practice. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.Paper 1081. http://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=theses. Published 2014. Accessed October 1, 2017.

39. Frankel AS, Alban A. Professional wills: protecting patients, family members and colleagues. The Steve Frankel Group. https://www.sfrankelgroup.com/professional-wills.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.