User login

Online dating and personal information: Pause before you post

Most adults want to have happy romantic relationships. But meeting eligible companions and finding the time to date can feel nearly impossible to many physicians, especially residents, whose 80-hour work weeks limit opportunities to meet potential partners.1

So it’s no surprise that Dr. R’s friends have suggested that she try online dating. If she does, she would be far from alone: 15% of U.S. adults have sought relationships online, and one-fourth of people in their 20s have used a mobile dating app.2,3 Online dating might work well for Dr. R, too. Between 2005 and 2012, more than one-third of U.S. marriages started online, and these marriages seemed happier and ended in separation or divorce less often than marriages that started in more traditional ways.4

Online dating is just one example of how “the permeation of online and social media into everyday life is placing doctors in new situations that they find difficult to navigate.”5 Many physicians—psychiatrists among them—date online. Yet, like Dr. R, physicians are cautious about using social media because of worries about public exposure and legal concerns.5 Moreover, medical associations haven’t developed guidelines that would help physicians reconcile their professional and personal lives if they seek companionship online.6

Although we don’t have complete answers to Dr. R’s questions, we have gathered some ideas and information that she might find helpful. Read on as we explore:

- potential benefits for psychiatrists who try online dating

- problems when physicians use social media

- how to minimize mishaps if you seek companionship online.

Advantages and benefits

Online dating is most popular among young adults. But singles and divorcees of all ages, sexual orientations, and backgrounds are increasingly seeking long-term relationships with internet-based dating tools rather than hoping to meet people through family, friends, church, and the workplace. It has become common—and no longer stigmatizing—for couples to say they met online.2,7

A dating Web site or app is a simple, fast, low-investment way to increase your opportunities to meet other singles and to make contact with more potential partners than you would meet otherwise. This is particularly helpful for people in thinner dating markets (eg, gays, lesbians, middle-age heterosexuals, and rural dwellers) or people seeking a companion of a particular type or lifestyle.7,8 Many internet dating tools claim that their matching algorithms can increase your chances of meeting someone you will find compatible (although research questions whether the algorithms really work8). Dating sites and apps also let users engage in brief, computer-mediated communications that can foster greater attraction and comfort before meeting for a first date.8

Appeal to psychiatrists

Online dating may have special appeal to young psychiatrists such as Dr. R. Oddly enough, being a mental health professional can leave you socially isolated. Many people react cautiously when they learn you are a psychiatrist—they think you are evaluating them (and let’s face it: often, this is true).9 Psychiatrists should be cordial but circumspect in conducting work relationships, which limits the type and amount of social life they might generate in the setting where many people meet their future spouses.10

Online dating can help single psychiatrists overcome these barriers. Scientifically minded physicians can find plenty of research-grounded advice for improving online dating chances.11-14 Two medical researchers even published a meta-analysis of evidence-based methods that can improve the chances of converting online contacts to a first date.15

Caution: Hazards ahead

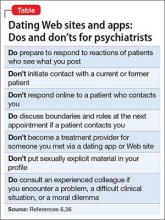

When seeking romance online, psychiatrists shouldn’t forget their professional obligations, including the duty to maintain clear boundaries between their social and work lives.16 If Dr. R decides to try online dating, she will be making it possible for curious patients to gain access to some of her personal information. She will have to figure out how to avoid jeopardizing her professional reputation or inadvertently opening the door to sexual misconduct.17

Boundaries online. Psychiatrists use the term “boundaries” to refer to how they structure appointments and monitor their behavior during therapy to keep the treatment relationship free of personal, sexual, and romantic influences. Keeping one’s emotional life out of treatment helps prevent exploitation of patients and fosters a sense of safety and assurance that the physician is acting solely with the patient’s interest in mind. Breaching boundaries in ways that exploit patients or serve the doctor’s needs can undermine treatment, harm patients, and result in serious professional consequences.18

Maintaining appropriate boundaries can be challenging for psychiatrists who want to date online because the outside-the-office context can muddy the distinction between one’s professional and personal identity. Online dating environments make it easier for physicians to inadvertently initiate social or romantic interactions with people they have treated but don’t recognize (something the authors know has happened to colleagues). Additionally, the internet’s anonymity leaves users vulnerable to being lured into interactions with someone who is using a fictional online persona—an activity colloquially called “catfishing.”19

Although patients may play an active role in boundary breaches, the physician bears sole responsibility for maintaining proper limits within the therapeutic relationship.18 For many psychiatrists, innocuous but non-professional interactions with patients have been the first steps down a “slippery slope” toward serious boundary violations, including sexual contact—an activity that both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Psychiatric Association deem categorically unethical and that can lead to malpractice lawsuits, sanctions by medical license boards, and (in some jurisdictions) criminal prosecution.20 When using social media and online dating tools, psychiatrists should avoid even seemingly minor boundary violations as a safeguard against more serious transgressions.20,21

Reports of online misconduct by medical trainees and practitioners are plentiful.22,23 In response, several medical organizations, including the AMA and the American College of Physicians, have developed professional guidelines for appropriate behavior on social media by physicians.24,25 These guidelines stress the importance of maintaining a professional presence when one’s online activity is publicly viewable.

How much self-disclosure is appropriate?

Traditionally, psychiatrists (including psychoanalysts) have felt that occasional, limited, well-considered references to oneself are acceptable and even helpful in treatment.26 The majority of therapists report using therapy-relevant self-disclosure, but they are cautious about what they say. Conscientious therapists avoid self-disclosure to satisfy their own needs, and they avoid self-disclosure with patients for whom it would have detrimental effects.18,27

Dating Web sites contain a lot of personal information that physicians don’t usually share with patients. Although physicians who use social media are advised to be careful about the information they make available to the public,28 this is more difficult to do with dating applications, where revealing some information about yourself is necessary for making meaningful connections. Creating an online dating profile means that you are potentially letting patients or patients’ relatives know about your place of residence, income, sexual orientation, number of children, and interests. You will need to think about how you will respond if a patient unexpectedly comments on your dating profile during a session or asks you out.

Beyond creating awkward situations, self-disclosure can have treatment implications, and it’s impossible to know how a particular comment will affect a particular client in a particular situation.29 Psychiatrists who engage in online dating may want to limit their posted personal information only to what they would feel reasonably comfortable with having patients know about them, and hope this will suffice to capture the attention of potential partners.

Sustaining professionalism while remaining human. The term “medical professionalism” originally referred to ethical conduct during the practice of medicine30 and to sustaining one’s commitment to patients, fellow professionals, and the institutions within which health care is provided.31 More recently, however, discussions of medical professionalism have encompassed how physicians comport themselves away from work. Physicians’ actions outside the office or hospital—and especially what they say, do, or post online—have a powerful effect on perceptions of their institutions and the medical profession as a whole.25,32

Photos and comments posted by physicians can be seen by millions and can have major repercussions for employment prospects and public perceptions.25 Questionable postings by physicians on social media outlets have resulted in disciplinary actions by licensing authorities and have damaged physicians’ careers.23

What seems appropriate for a dating Web site varies from person to person. A suggestive smile or flirtatious joke that most people would find harmless may strike others as provocative. Derogatory language, depictions of intoxication or substance abuse, and inappropriate patient-related comments are clear-cut mistakes.32-34 But also keep in mind that what medical professionals find acceptable to post on social networking sites does not always match what the general public thinks.35

Bottom Line

1. Miller JA. Romance in residency: is dating even possible? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844059. Published May 5, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

2. Smith A, Anderson M. 5 facts about online dating. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating. Published February 29, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

3. Smith A. 15% of American adults have used online dating sites or mobile dating apps. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/02/11/15-percent-of-american-adults-have-used-online-dating-sites-or-mobile-dating-apps/. Published February 11, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

4. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Gonzaga GC, et al. Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(25):10135-10140.

5. Brown J, Ryan C, Harris A. How doctors view and use social media: a national survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e267.

6. Berlin R. The professional ethics of online dating: need for guidance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(9):935-937.

7. Rosenfeld MJ, Thomas RJ. Searching for a mate: the rise of the Internet as a social intermediary. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):523-547.

8. Finkel EJ, Eastwick PW, Karney BR, et al. Online dating: a critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(1):3-66.

9. Pierre J. A mad world: a diagnosis of mental illness is more common than ever—did psychiatrists create the problem, or just recognise it? Aeon.co. https://aeon.co/essays/do-psychiatrists-really-think-that-everyone-is-crazy. Published March 19, 2014. Accessed June 28, 2016.

10. Pearce A, Gambrell D. This chart shows who marries CEOs, doctors, chefs and janitors. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2016-who-marries-whom. February 11, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

11. Lowin R. Proofread that text before sending! Bad grammar is a dating deal breaker, most say. Today. http://www.today.com/health/can-your-awesome-grammar-really-get-you-date-according-new-t77376. Published March 2, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

12. Reilly K. This strategy will make your Tinder game much stronger. Time. http://time.com/4263598/tinder-gif-messages-response-rate. Published March 17, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

13. Wotipka CD, High AC. Providing a foundation for a satisfying relationship: a direct test of warranting versus selective self-presentation as predictors of attraction to online dating profiles. Presentation at the 101st Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association; November 20, 2014; Chicago, IL.

14. Vacharkulksemsuk T, Reit E, Khambatta P, et al. Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(15):4009-4014.

15. Khan KS, Chaudhry S. An evidence-based approach to an ancient pursuit: systematic review on converting online contact into a first date. Evid Based Med. 2015;20(2):48-56.

16. Chretien KC, Tuck MG. Online professionalism: a synthetic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):106-117.

17. Jackson WC. When patients are normal people: strategies for managing dual relationships. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(3):100-103.

18. Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO. The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(2):188-196.

19. D’Costa K. Catfishing: the truth about deception online. ScientificAmerican.com. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/catfishing-the-truth-about-deception-online. Published April 25, 2014. Accessed June 29, 2016.

20. Sarkar SP. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(4):312-320.

21. Nadelson C, Notman MT. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002;23(3):191-201.

22. Walton JM, White J, Ross S. What’s on YOUR Facebook profile? Evaluation of an educational intervention to promote appropriate use of privacy settings by medical students on social networking sites. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:28708. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28708.

23. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

24. Decamp M. Physicians, social media, and conflict of interest. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):299-303.

25. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al; American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee; American College of Physicians Council of Associates; Federation of State Medical Boards Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620-627.

26. Meissner WW. The problem of self-disclosure in psychoanalysis. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2002;50(3):827-867.

27. Henretty JR, Levitt HM. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: a qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(1):63-77.

28. Ponce BA, Determann JR, Boohaker HA, et al. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: an original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(4):502-507.

29. Peterson ZD. More than a mirror: the ethics of therapist self-disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory Research & Practice. 2002;39(1):21-31.

30. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226-235.

31. Wass V. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Clin Med (Lond). 2006;6(1):109-113.

32. Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, et al. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: a warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e28-e32.

33. Chauhan B, George R, Coffin J. Social media and you: what every physician needs to know. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28(3):206-209.

34. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

35. Jain A, Petty EM, Jaber RM, et al. What is appropriate to post on social media? Ratings from students, faculty members and the public. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):157-169.

36. Gabbard GO, Roberts LW, Crisp-Han H, et al. Professionalism in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2012.

Most adults want to have happy romantic relationships. But meeting eligible companions and finding the time to date can feel nearly impossible to many physicians, especially residents, whose 80-hour work weeks limit opportunities to meet potential partners.1

So it’s no surprise that Dr. R’s friends have suggested that she try online dating. If she does, she would be far from alone: 15% of U.S. adults have sought relationships online, and one-fourth of people in their 20s have used a mobile dating app.2,3 Online dating might work well for Dr. R, too. Between 2005 and 2012, more than one-third of U.S. marriages started online, and these marriages seemed happier and ended in separation or divorce less often than marriages that started in more traditional ways.4

Online dating is just one example of how “the permeation of online and social media into everyday life is placing doctors in new situations that they find difficult to navigate.”5 Many physicians—psychiatrists among them—date online. Yet, like Dr. R, physicians are cautious about using social media because of worries about public exposure and legal concerns.5 Moreover, medical associations haven’t developed guidelines that would help physicians reconcile their professional and personal lives if they seek companionship online.6

Although we don’t have complete answers to Dr. R’s questions, we have gathered some ideas and information that she might find helpful. Read on as we explore:

- potential benefits for psychiatrists who try online dating

- problems when physicians use social media

- how to minimize mishaps if you seek companionship online.

Advantages and benefits

Online dating is most popular among young adults. But singles and divorcees of all ages, sexual orientations, and backgrounds are increasingly seeking long-term relationships with internet-based dating tools rather than hoping to meet people through family, friends, church, and the workplace. It has become common—and no longer stigmatizing—for couples to say they met online.2,7

A dating Web site or app is a simple, fast, low-investment way to increase your opportunities to meet other singles and to make contact with more potential partners than you would meet otherwise. This is particularly helpful for people in thinner dating markets (eg, gays, lesbians, middle-age heterosexuals, and rural dwellers) or people seeking a companion of a particular type or lifestyle.7,8 Many internet dating tools claim that their matching algorithms can increase your chances of meeting someone you will find compatible (although research questions whether the algorithms really work8). Dating sites and apps also let users engage in brief, computer-mediated communications that can foster greater attraction and comfort before meeting for a first date.8

Appeal to psychiatrists

Online dating may have special appeal to young psychiatrists such as Dr. R. Oddly enough, being a mental health professional can leave you socially isolated. Many people react cautiously when they learn you are a psychiatrist—they think you are evaluating them (and let’s face it: often, this is true).9 Psychiatrists should be cordial but circumspect in conducting work relationships, which limits the type and amount of social life they might generate in the setting where many people meet their future spouses.10

Online dating can help single psychiatrists overcome these barriers. Scientifically minded physicians can find plenty of research-grounded advice for improving online dating chances.11-14 Two medical researchers even published a meta-analysis of evidence-based methods that can improve the chances of converting online contacts to a first date.15

Caution: Hazards ahead

When seeking romance online, psychiatrists shouldn’t forget their professional obligations, including the duty to maintain clear boundaries between their social and work lives.16 If Dr. R decides to try online dating, she will be making it possible for curious patients to gain access to some of her personal information. She will have to figure out how to avoid jeopardizing her professional reputation or inadvertently opening the door to sexual misconduct.17

Boundaries online. Psychiatrists use the term “boundaries” to refer to how they structure appointments and monitor their behavior during therapy to keep the treatment relationship free of personal, sexual, and romantic influences. Keeping one’s emotional life out of treatment helps prevent exploitation of patients and fosters a sense of safety and assurance that the physician is acting solely with the patient’s interest in mind. Breaching boundaries in ways that exploit patients or serve the doctor’s needs can undermine treatment, harm patients, and result in serious professional consequences.18

Maintaining appropriate boundaries can be challenging for psychiatrists who want to date online because the outside-the-office context can muddy the distinction between one’s professional and personal identity. Online dating environments make it easier for physicians to inadvertently initiate social or romantic interactions with people they have treated but don’t recognize (something the authors know has happened to colleagues). Additionally, the internet’s anonymity leaves users vulnerable to being lured into interactions with someone who is using a fictional online persona—an activity colloquially called “catfishing.”19

Although patients may play an active role in boundary breaches, the physician bears sole responsibility for maintaining proper limits within the therapeutic relationship.18 For many psychiatrists, innocuous but non-professional interactions with patients have been the first steps down a “slippery slope” toward serious boundary violations, including sexual contact—an activity that both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Psychiatric Association deem categorically unethical and that can lead to malpractice lawsuits, sanctions by medical license boards, and (in some jurisdictions) criminal prosecution.20 When using social media and online dating tools, psychiatrists should avoid even seemingly minor boundary violations as a safeguard against more serious transgressions.20,21

Reports of online misconduct by medical trainees and practitioners are plentiful.22,23 In response, several medical organizations, including the AMA and the American College of Physicians, have developed professional guidelines for appropriate behavior on social media by physicians.24,25 These guidelines stress the importance of maintaining a professional presence when one’s online activity is publicly viewable.

How much self-disclosure is appropriate?

Traditionally, psychiatrists (including psychoanalysts) have felt that occasional, limited, well-considered references to oneself are acceptable and even helpful in treatment.26 The majority of therapists report using therapy-relevant self-disclosure, but they are cautious about what they say. Conscientious therapists avoid self-disclosure to satisfy their own needs, and they avoid self-disclosure with patients for whom it would have detrimental effects.18,27

Dating Web sites contain a lot of personal information that physicians don’t usually share with patients. Although physicians who use social media are advised to be careful about the information they make available to the public,28 this is more difficult to do with dating applications, where revealing some information about yourself is necessary for making meaningful connections. Creating an online dating profile means that you are potentially letting patients or patients’ relatives know about your place of residence, income, sexual orientation, number of children, and interests. You will need to think about how you will respond if a patient unexpectedly comments on your dating profile during a session or asks you out.

Beyond creating awkward situations, self-disclosure can have treatment implications, and it’s impossible to know how a particular comment will affect a particular client in a particular situation.29 Psychiatrists who engage in online dating may want to limit their posted personal information only to what they would feel reasonably comfortable with having patients know about them, and hope this will suffice to capture the attention of potential partners.

Sustaining professionalism while remaining human. The term “medical professionalism” originally referred to ethical conduct during the practice of medicine30 and to sustaining one’s commitment to patients, fellow professionals, and the institutions within which health care is provided.31 More recently, however, discussions of medical professionalism have encompassed how physicians comport themselves away from work. Physicians’ actions outside the office or hospital—and especially what they say, do, or post online—have a powerful effect on perceptions of their institutions and the medical profession as a whole.25,32

Photos and comments posted by physicians can be seen by millions and can have major repercussions for employment prospects and public perceptions.25 Questionable postings by physicians on social media outlets have resulted in disciplinary actions by licensing authorities and have damaged physicians’ careers.23

What seems appropriate for a dating Web site varies from person to person. A suggestive smile or flirtatious joke that most people would find harmless may strike others as provocative. Derogatory language, depictions of intoxication or substance abuse, and inappropriate patient-related comments are clear-cut mistakes.32-34 But also keep in mind that what medical professionals find acceptable to post on social networking sites does not always match what the general public thinks.35

Bottom Line

Most adults want to have happy romantic relationships. But meeting eligible companions and finding the time to date can feel nearly impossible to many physicians, especially residents, whose 80-hour work weeks limit opportunities to meet potential partners.1

So it’s no surprise that Dr. R’s friends have suggested that she try online dating. If she does, she would be far from alone: 15% of U.S. adults have sought relationships online, and one-fourth of people in their 20s have used a mobile dating app.2,3 Online dating might work well for Dr. R, too. Between 2005 and 2012, more than one-third of U.S. marriages started online, and these marriages seemed happier and ended in separation or divorce less often than marriages that started in more traditional ways.4

Online dating is just one example of how “the permeation of online and social media into everyday life is placing doctors in new situations that they find difficult to navigate.”5 Many physicians—psychiatrists among them—date online. Yet, like Dr. R, physicians are cautious about using social media because of worries about public exposure and legal concerns.5 Moreover, medical associations haven’t developed guidelines that would help physicians reconcile their professional and personal lives if they seek companionship online.6

Although we don’t have complete answers to Dr. R’s questions, we have gathered some ideas and information that she might find helpful. Read on as we explore:

- potential benefits for psychiatrists who try online dating

- problems when physicians use social media

- how to minimize mishaps if you seek companionship online.

Advantages and benefits

Online dating is most popular among young adults. But singles and divorcees of all ages, sexual orientations, and backgrounds are increasingly seeking long-term relationships with internet-based dating tools rather than hoping to meet people through family, friends, church, and the workplace. It has become common—and no longer stigmatizing—for couples to say they met online.2,7

A dating Web site or app is a simple, fast, low-investment way to increase your opportunities to meet other singles and to make contact with more potential partners than you would meet otherwise. This is particularly helpful for people in thinner dating markets (eg, gays, lesbians, middle-age heterosexuals, and rural dwellers) or people seeking a companion of a particular type or lifestyle.7,8 Many internet dating tools claim that their matching algorithms can increase your chances of meeting someone you will find compatible (although research questions whether the algorithms really work8). Dating sites and apps also let users engage in brief, computer-mediated communications that can foster greater attraction and comfort before meeting for a first date.8

Appeal to psychiatrists

Online dating may have special appeal to young psychiatrists such as Dr. R. Oddly enough, being a mental health professional can leave you socially isolated. Many people react cautiously when they learn you are a psychiatrist—they think you are evaluating them (and let’s face it: often, this is true).9 Psychiatrists should be cordial but circumspect in conducting work relationships, which limits the type and amount of social life they might generate in the setting where many people meet their future spouses.10

Online dating can help single psychiatrists overcome these barriers. Scientifically minded physicians can find plenty of research-grounded advice for improving online dating chances.11-14 Two medical researchers even published a meta-analysis of evidence-based methods that can improve the chances of converting online contacts to a first date.15

Caution: Hazards ahead

When seeking romance online, psychiatrists shouldn’t forget their professional obligations, including the duty to maintain clear boundaries between their social and work lives.16 If Dr. R decides to try online dating, she will be making it possible for curious patients to gain access to some of her personal information. She will have to figure out how to avoid jeopardizing her professional reputation or inadvertently opening the door to sexual misconduct.17

Boundaries online. Psychiatrists use the term “boundaries” to refer to how they structure appointments and monitor their behavior during therapy to keep the treatment relationship free of personal, sexual, and romantic influences. Keeping one’s emotional life out of treatment helps prevent exploitation of patients and fosters a sense of safety and assurance that the physician is acting solely with the patient’s interest in mind. Breaching boundaries in ways that exploit patients or serve the doctor’s needs can undermine treatment, harm patients, and result in serious professional consequences.18

Maintaining appropriate boundaries can be challenging for psychiatrists who want to date online because the outside-the-office context can muddy the distinction between one’s professional and personal identity. Online dating environments make it easier for physicians to inadvertently initiate social or romantic interactions with people they have treated but don’t recognize (something the authors know has happened to colleagues). Additionally, the internet’s anonymity leaves users vulnerable to being lured into interactions with someone who is using a fictional online persona—an activity colloquially called “catfishing.”19

Although patients may play an active role in boundary breaches, the physician bears sole responsibility for maintaining proper limits within the therapeutic relationship.18 For many psychiatrists, innocuous but non-professional interactions with patients have been the first steps down a “slippery slope” toward serious boundary violations, including sexual contact—an activity that both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Psychiatric Association deem categorically unethical and that can lead to malpractice lawsuits, sanctions by medical license boards, and (in some jurisdictions) criminal prosecution.20 When using social media and online dating tools, psychiatrists should avoid even seemingly minor boundary violations as a safeguard against more serious transgressions.20,21

Reports of online misconduct by medical trainees and practitioners are plentiful.22,23 In response, several medical organizations, including the AMA and the American College of Physicians, have developed professional guidelines for appropriate behavior on social media by physicians.24,25 These guidelines stress the importance of maintaining a professional presence when one’s online activity is publicly viewable.

How much self-disclosure is appropriate?

Traditionally, psychiatrists (including psychoanalysts) have felt that occasional, limited, well-considered references to oneself are acceptable and even helpful in treatment.26 The majority of therapists report using therapy-relevant self-disclosure, but they are cautious about what they say. Conscientious therapists avoid self-disclosure to satisfy their own needs, and they avoid self-disclosure with patients for whom it would have detrimental effects.18,27

Dating Web sites contain a lot of personal information that physicians don’t usually share with patients. Although physicians who use social media are advised to be careful about the information they make available to the public,28 this is more difficult to do with dating applications, where revealing some information about yourself is necessary for making meaningful connections. Creating an online dating profile means that you are potentially letting patients or patients’ relatives know about your place of residence, income, sexual orientation, number of children, and interests. You will need to think about how you will respond if a patient unexpectedly comments on your dating profile during a session or asks you out.

Beyond creating awkward situations, self-disclosure can have treatment implications, and it’s impossible to know how a particular comment will affect a particular client in a particular situation.29 Psychiatrists who engage in online dating may want to limit their posted personal information only to what they would feel reasonably comfortable with having patients know about them, and hope this will suffice to capture the attention of potential partners.

Sustaining professionalism while remaining human. The term “medical professionalism” originally referred to ethical conduct during the practice of medicine30 and to sustaining one’s commitment to patients, fellow professionals, and the institutions within which health care is provided.31 More recently, however, discussions of medical professionalism have encompassed how physicians comport themselves away from work. Physicians’ actions outside the office or hospital—and especially what they say, do, or post online—have a powerful effect on perceptions of their institutions and the medical profession as a whole.25,32

Photos and comments posted by physicians can be seen by millions and can have major repercussions for employment prospects and public perceptions.25 Questionable postings by physicians on social media outlets have resulted in disciplinary actions by licensing authorities and have damaged physicians’ careers.23

What seems appropriate for a dating Web site varies from person to person. A suggestive smile or flirtatious joke that most people would find harmless may strike others as provocative. Derogatory language, depictions of intoxication or substance abuse, and inappropriate patient-related comments are clear-cut mistakes.32-34 But also keep in mind that what medical professionals find acceptable to post on social networking sites does not always match what the general public thinks.35

Bottom Line

1. Miller JA. Romance in residency: is dating even possible? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844059. Published May 5, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

2. Smith A, Anderson M. 5 facts about online dating. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating. Published February 29, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

3. Smith A. 15% of American adults have used online dating sites or mobile dating apps. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/02/11/15-percent-of-american-adults-have-used-online-dating-sites-or-mobile-dating-apps/. Published February 11, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

4. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Gonzaga GC, et al. Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(25):10135-10140.

5. Brown J, Ryan C, Harris A. How doctors view and use social media: a national survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e267.

6. Berlin R. The professional ethics of online dating: need for guidance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(9):935-937.

7. Rosenfeld MJ, Thomas RJ. Searching for a mate: the rise of the Internet as a social intermediary. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):523-547.

8. Finkel EJ, Eastwick PW, Karney BR, et al. Online dating: a critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(1):3-66.

9. Pierre J. A mad world: a diagnosis of mental illness is more common than ever—did psychiatrists create the problem, or just recognise it? Aeon.co. https://aeon.co/essays/do-psychiatrists-really-think-that-everyone-is-crazy. Published March 19, 2014. Accessed June 28, 2016.

10. Pearce A, Gambrell D. This chart shows who marries CEOs, doctors, chefs and janitors. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2016-who-marries-whom. February 11, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

11. Lowin R. Proofread that text before sending! Bad grammar is a dating deal breaker, most say. Today. http://www.today.com/health/can-your-awesome-grammar-really-get-you-date-according-new-t77376. Published March 2, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

12. Reilly K. This strategy will make your Tinder game much stronger. Time. http://time.com/4263598/tinder-gif-messages-response-rate. Published March 17, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

13. Wotipka CD, High AC. Providing a foundation for a satisfying relationship: a direct test of warranting versus selective self-presentation as predictors of attraction to online dating profiles. Presentation at the 101st Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association; November 20, 2014; Chicago, IL.

14. Vacharkulksemsuk T, Reit E, Khambatta P, et al. Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(15):4009-4014.

15. Khan KS, Chaudhry S. An evidence-based approach to an ancient pursuit: systematic review on converting online contact into a first date. Evid Based Med. 2015;20(2):48-56.

16. Chretien KC, Tuck MG. Online professionalism: a synthetic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):106-117.

17. Jackson WC. When patients are normal people: strategies for managing dual relationships. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(3):100-103.

18. Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO. The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(2):188-196.

19. D’Costa K. Catfishing: the truth about deception online. ScientificAmerican.com. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/catfishing-the-truth-about-deception-online. Published April 25, 2014. Accessed June 29, 2016.

20. Sarkar SP. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(4):312-320.

21. Nadelson C, Notman MT. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002;23(3):191-201.

22. Walton JM, White J, Ross S. What’s on YOUR Facebook profile? Evaluation of an educational intervention to promote appropriate use of privacy settings by medical students on social networking sites. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:28708. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28708.

23. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

24. Decamp M. Physicians, social media, and conflict of interest. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):299-303.

25. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al; American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee; American College of Physicians Council of Associates; Federation of State Medical Boards Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620-627.

26. Meissner WW. The problem of self-disclosure in psychoanalysis. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2002;50(3):827-867.

27. Henretty JR, Levitt HM. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: a qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(1):63-77.

28. Ponce BA, Determann JR, Boohaker HA, et al. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: an original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(4):502-507.

29. Peterson ZD. More than a mirror: the ethics of therapist self-disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory Research & Practice. 2002;39(1):21-31.

30. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226-235.

31. Wass V. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Clin Med (Lond). 2006;6(1):109-113.

32. Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, et al. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: a warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e28-e32.

33. Chauhan B, George R, Coffin J. Social media and you: what every physician needs to know. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28(3):206-209.

34. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

35. Jain A, Petty EM, Jaber RM, et al. What is appropriate to post on social media? Ratings from students, faculty members and the public. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):157-169.

36. Gabbard GO, Roberts LW, Crisp-Han H, et al. Professionalism in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2012.

1. Miller JA. Romance in residency: is dating even possible? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844059. Published May 5, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

2. Smith A, Anderson M. 5 facts about online dating. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating. Published February 29, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

3. Smith A. 15% of American adults have used online dating sites or mobile dating apps. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/02/11/15-percent-of-american-adults-have-used-online-dating-sites-or-mobile-dating-apps/. Published February 11, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

4. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Gonzaga GC, et al. Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(25):10135-10140.

5. Brown J, Ryan C, Harris A. How doctors view and use social media: a national survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e267.

6. Berlin R. The professional ethics of online dating: need for guidance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(9):935-937.

7. Rosenfeld MJ, Thomas RJ. Searching for a mate: the rise of the Internet as a social intermediary. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):523-547.

8. Finkel EJ, Eastwick PW, Karney BR, et al. Online dating: a critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(1):3-66.

9. Pierre J. A mad world: a diagnosis of mental illness is more common than ever—did psychiatrists create the problem, or just recognise it? Aeon.co. https://aeon.co/essays/do-psychiatrists-really-think-that-everyone-is-crazy. Published March 19, 2014. Accessed June 28, 2016.

10. Pearce A, Gambrell D. This chart shows who marries CEOs, doctors, chefs and janitors. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2016-who-marries-whom. February 11, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

11. Lowin R. Proofread that text before sending! Bad grammar is a dating deal breaker, most say. Today. http://www.today.com/health/can-your-awesome-grammar-really-get-you-date-according-new-t77376. Published March 2, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

12. Reilly K. This strategy will make your Tinder game much stronger. Time. http://time.com/4263598/tinder-gif-messages-response-rate. Published March 17, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

13. Wotipka CD, High AC. Providing a foundation for a satisfying relationship: a direct test of warranting versus selective self-presentation as predictors of attraction to online dating profiles. Presentation at the 101st Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association; November 20, 2014; Chicago, IL.

14. Vacharkulksemsuk T, Reit E, Khambatta P, et al. Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(15):4009-4014.

15. Khan KS, Chaudhry S. An evidence-based approach to an ancient pursuit: systematic review on converting online contact into a first date. Evid Based Med. 2015;20(2):48-56.

16. Chretien KC, Tuck MG. Online professionalism: a synthetic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):106-117.

17. Jackson WC. When patients are normal people: strategies for managing dual relationships. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(3):100-103.

18. Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO. The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(2):188-196.

19. D’Costa K. Catfishing: the truth about deception online. ScientificAmerican.com. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/catfishing-the-truth-about-deception-online. Published April 25, 2014. Accessed June 29, 2016.

20. Sarkar SP. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(4):312-320.

21. Nadelson C, Notman MT. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002;23(3):191-201.

22. Walton JM, White J, Ross S. What’s on YOUR Facebook profile? Evaluation of an educational intervention to promote appropriate use of privacy settings by medical students on social networking sites. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:28708. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28708.

23. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

24. Decamp M. Physicians, social media, and conflict of interest. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):299-303.

25. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al; American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee; American College of Physicians Council of Associates; Federation of State Medical Boards Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620-627.

26. Meissner WW. The problem of self-disclosure in psychoanalysis. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2002;50(3):827-867.

27. Henretty JR, Levitt HM. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: a qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(1):63-77.

28. Ponce BA, Determann JR, Boohaker HA, et al. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: an original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(4):502-507.

29. Peterson ZD. More than a mirror: the ethics of therapist self-disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory Research & Practice. 2002;39(1):21-31.

30. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226-235.

31. Wass V. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Clin Med (Lond). 2006;6(1):109-113.

32. Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, et al. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: a warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e28-e32.

33. Chauhan B, George R, Coffin J. Social media and you: what every physician needs to know. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28(3):206-209.

34. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

35. Jain A, Petty EM, Jaber RM, et al. What is appropriate to post on social media? Ratings from students, faculty members and the public. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):157-169.

36. Gabbard GO, Roberts LW, Crisp-Han H, et al. Professionalism in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2012.