User login

Before you hit 'send': Will an e-mail to your patient put you at legal risk?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Some of my patients e-mail me questions about their prescriptions, test results, treatment, appointments, etc. I’m often unsure about the best way to respond. If I use e-mail to communicate with patients, what step(s) should I take to minimize medicolegal risks?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Medicine adopts new communication technologies cautiously. Calling patients seems unremarkable to us now, but it took decades after the invention of the telephone for doctors to feel comfortable talking to patients other than in face-to-face meetings.1,2

Patients want to communicate with their physicians via electronic mail,3 but concerns about security, confidentiality, and liability stop many physicians from using e-mail in their practice. Yet many medical organizations, including the Institute of Medicine,4 the American Medical Association,5 and the American Psychiatric Association,6 recognize that e-mail can facilitate care, if used properly.

Although e-mailing patients may feel awkward, a growing minority of clinicians regularly use e-mail for patient communication.2,7 In this article, we discuss ways to help safeguard your patients and their communications and to protect yourself from legal headaches.8

As you’re reading, please remember that we’re discussing communications to patients through standard e-mail, not secure portals (such as MyChart) that allow patients to contact physicians confidentially through their electronic medical records.

Privacy and security

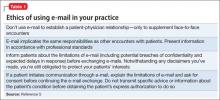

Doctor-patient e-mails implicate the same professional, ethical, and legal responsibilities that govern any communication with patients.2,9,10 If handled improperly, outside-the-office doctor-patient communication can breach traditional duties to protect confidentiality, or they can violate provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).11 Confidentiality breaches can lead to malpractice litigation, and HIPAA infractions can result in civil and criminal penalties levied by federal agencies.12 Further, e-mails that breach ethical standards (Table 15) can generate complaints to your state’s medical licensure board.

E-mail appeals to many patients, if for no other reason than to save time or avoid the inconvenience of playing “phone tag” with the doctor’s office. But e-mail has drawbacks. Patients may think or behave as though online communications are intimate and confidential, but they usually aren’t. If e-mail programs are left open or aren’t password protected, friends and family members might look at messages and even act upon them. For this reason, doctors often cannot be sure whether they are communicating with the patient or with someone else who has gained access to the patient’s e-mail account.

Parties outside the treatment relationship could have access to e-mail data stored on servers.6 Also, it’s easy to misread or mistype an e-mail address and send confidential information to the wrong person. A truly “secure” e-mail exchange uses encryption software that protects messages during transmission and storage and requires users to authenticate who they are through actions that link their identity to the e-mail address.13 But some patients and physicians do not know about the availability of such security measures, and implementing them can feel cumbersome to those who are not computer savvy. Not surprisingly, then, recent studies have shown that such measures are used infrequently by physicians and patients.14

Topics for e-mail communication

One way to minimize potential privacy problems is to limit the topics and types of communication dealt with by e-mail. Several experts and organizations have published suggestions, recommendations, and resources for doing this with common practices (Table 2).6,7,15

Receiving e-mail permission

Many patients e-mail their physicians without the physicians’ prior agreement. But physicians who plan to use e-mail in their practice should get patients’ explicit consent. This can be done verbally, with the content of the discussion documented in the medical record. But it’s better to have patients authorize e-mail communications in writing by means of a permission form that also sets out your office’s e-mail policies, expected response times, and privacy limitations.

Commonly recommended contents of such forms5-7,9,15,16 include:

• discussing security mechanisms and limits of security

• e-mail encryption requirements (or waiving them, if the patient prefers)

• providing an expected response time

• indemnifying you or your institution for information loss caused by technical failure

• identifying who reads e-mails (eg, office staff members, a nurse, physician [only])

• asking patients to put their name and other identifying information in the body of the message, not the subject line

• asking patients to put the type of question in the subject line (eg, “prescription,” “appointment,” “billing”)

• asking patients to use the “auto reply” feature to acknowledge receipt of your messages.

In addition to using patient consent forms, other suggestions and recommendations for physicians include:

• Do not use e-mail to establish patient-physician relationships, only to supplement personal encounters.

• If you work for an agency or institution, know and follow its guidelines and policies.

• If a rule or “boundary” is breached (eg, a patient sends you a detailed e-mail on a topic beyond the scope of your previous agreement), address this directly in a treatment session.

• File e-mail correspondence, including your reply, in the patient’s medical record.

• Use encryption technology if it is available, practical, and user-friendly.

• Use a practice-dedicated e-mail address with an automatic response that explains when e-mail will be answered and reminds patients to seek immediate help for urgent matters.

Real legal risk

Earlier, we described conceivable legal risks that e-mail might create. But has e-mail caused legal problems for physicians? At least 3 recent published decisions answer: “Yes.” And, remember, only a fraction of legal cases lead to published decisions.

• Huffine v Department of Health17 concerns a psychiatrist who was censured by the Washington state medical quality assurance commission for several boundary crossings, including sending his adolescent patient overly intimate e-mails.

• Wheeler v Kron18 lists a variety of legal claims—intentional infliction of emotional distress, negligent infliction of emotional distress, general negligence, and medical malpractice—that arose from a psychiatrist’s e-mailed concerns about visitation arrangements in a divorcing couple’s custody dispute. Although the court dismissed the last 3 claims, it allowed the intentional infliction of emotional distress claim to proceed.

• Ortegoza v Kho19 includes excerpts of e-mails between a primary care physician and his married patient, with whom the physician had affair that led to a medical malpractice lawsuit.

Bottom Line

Most patients want to e-mail their physicians, and many psychiatrists find e-mail helpful in caring for patients. If you are using e-mail in your practice or are contemplating doing so, get the patient’s permission (preferably in writing), and follow the recommendations and guidelines cited in this article’s references.

Related Resources

• Kane B, Sands DZ. Guidelines for the clinical use of electronic mail with patients. http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/1/104.long.

• Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. Sample email consent and guide to email use. www.psychprogram.com/currentpsychiatry.html.

1. Wieczorek SM. From telegraph to e-mail: preserving the doctor-patient relationship in a high-tech environment. ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 2010;67(3):311-327.

2. Spielberg AR. Online without a net: physician-patient communication by electronic mail. Am J Law Med. 1999;25(2-3):267-295.

3. Pelletier AL, Sutton GR, Walker RR. Are your patients ready for electronic communication? Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(9):25-26.

4. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

5. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Opinion 5.026 - the use of electronic mail. http:// www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/ medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion5026.page. Published June 2013. Accessed March 8, 2015.

6. American Psychiatric Association, Council on Psychiatry & Law. Resource document on telepsychiatry and related technologies in clinical psychiatry. http://www.psychiatry. org/learn/library--archives/resource-documents. Published January 2014. Accessed March 25, 2015.

7. Koh S, Cattell GM, Cochran DM, et al. Psychiatrists’ use of electronic communication and social media and a proposed framework for future guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(3):254-263.

8. Sands DZ. Help for physicians contemplating use of e-mail with patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(4):268-269.

9. Bovi AM; Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association. Ethical guidelines for use of electronic mail between patients and physicians. Am J Bioeth. 2003;3(3):W-IF2.

10. Kuszler PC. A question of duty: common law legal issues resulting from physician response to unsolicited patient email inquiries. J Med Internet Res. 2000;2(3):E17.

11. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164.

12. Vanderpool D. Hippa-should I be worried? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(11-12):51-55.

13. Tjora A, Tran T, Faxvaag A. Privacy vs. usability: a qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences with secure internet communication with their general practitioner. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(2):e15.

14. Menachemi N, Prickett CT, Brooks RG. The use of physician-patient email: a follow-up examination of adoption and best-practice adherence 2005-2008. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e23.

15. Kane B, Sands DZ. Guidelines for the clinical use of electronic mail with patients. The AMIA Internet Working Group, Task Force on guidelines for the use of clinic-patient electronic mail. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(1):104-111.

16. Car J, Sheikh A. Email consultations in health care: 2–acceptability and safe application. BMJ. 2004; 329(7463):439-442.

17. Huffine v Department of Health, 148 Wn App 1015 (Wash Ct App 2009).

18. Wheeler v Akron (NY Misc LEXIS 942, 2011) NY Slip Op 30530(U) (NY Misc 2011).

19. Ortegoza v Kho, 2013 U.S. Dist .LEXIS 69999 (SD Cal 2013).

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Some of my patients e-mail me questions about their prescriptions, test results, treatment, appointments, etc. I’m often unsure about the best way to respond. If I use e-mail to communicate with patients, what step(s) should I take to minimize medicolegal risks?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Medicine adopts new communication technologies cautiously. Calling patients seems unremarkable to us now, but it took decades after the invention of the telephone for doctors to feel comfortable talking to patients other than in face-to-face meetings.1,2

Patients want to communicate with their physicians via electronic mail,3 but concerns about security, confidentiality, and liability stop many physicians from using e-mail in their practice. Yet many medical organizations, including the Institute of Medicine,4 the American Medical Association,5 and the American Psychiatric Association,6 recognize that e-mail can facilitate care, if used properly.

Although e-mailing patients may feel awkward, a growing minority of clinicians regularly use e-mail for patient communication.2,7 In this article, we discuss ways to help safeguard your patients and their communications and to protect yourself from legal headaches.8

As you’re reading, please remember that we’re discussing communications to patients through standard e-mail, not secure portals (such as MyChart) that allow patients to contact physicians confidentially through their electronic medical records.

Privacy and security

Doctor-patient e-mails implicate the same professional, ethical, and legal responsibilities that govern any communication with patients.2,9,10 If handled improperly, outside-the-office doctor-patient communication can breach traditional duties to protect confidentiality, or they can violate provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).11 Confidentiality breaches can lead to malpractice litigation, and HIPAA infractions can result in civil and criminal penalties levied by federal agencies.12 Further, e-mails that breach ethical standards (Table 15) can generate complaints to your state’s medical licensure board.

E-mail appeals to many patients, if for no other reason than to save time or avoid the inconvenience of playing “phone tag” with the doctor’s office. But e-mail has drawbacks. Patients may think or behave as though online communications are intimate and confidential, but they usually aren’t. If e-mail programs are left open or aren’t password protected, friends and family members might look at messages and even act upon them. For this reason, doctors often cannot be sure whether they are communicating with the patient or with someone else who has gained access to the patient’s e-mail account.

Parties outside the treatment relationship could have access to e-mail data stored on servers.6 Also, it’s easy to misread or mistype an e-mail address and send confidential information to the wrong person. A truly “secure” e-mail exchange uses encryption software that protects messages during transmission and storage and requires users to authenticate who they are through actions that link their identity to the e-mail address.13 But some patients and physicians do not know about the availability of such security measures, and implementing them can feel cumbersome to those who are not computer savvy. Not surprisingly, then, recent studies have shown that such measures are used infrequently by physicians and patients.14

Topics for e-mail communication

One way to minimize potential privacy problems is to limit the topics and types of communication dealt with by e-mail. Several experts and organizations have published suggestions, recommendations, and resources for doing this with common practices (Table 2).6,7,15

Receiving e-mail permission

Many patients e-mail their physicians without the physicians’ prior agreement. But physicians who plan to use e-mail in their practice should get patients’ explicit consent. This can be done verbally, with the content of the discussion documented in the medical record. But it’s better to have patients authorize e-mail communications in writing by means of a permission form that also sets out your office’s e-mail policies, expected response times, and privacy limitations.

Commonly recommended contents of such forms5-7,9,15,16 include:

• discussing security mechanisms and limits of security

• e-mail encryption requirements (or waiving them, if the patient prefers)

• providing an expected response time

• indemnifying you or your institution for information loss caused by technical failure

• identifying who reads e-mails (eg, office staff members, a nurse, physician [only])

• asking patients to put their name and other identifying information in the body of the message, not the subject line

• asking patients to put the type of question in the subject line (eg, “prescription,” “appointment,” “billing”)

• asking patients to use the “auto reply” feature to acknowledge receipt of your messages.

In addition to using patient consent forms, other suggestions and recommendations for physicians include:

• Do not use e-mail to establish patient-physician relationships, only to supplement personal encounters.

• If you work for an agency or institution, know and follow its guidelines and policies.

• If a rule or “boundary” is breached (eg, a patient sends you a detailed e-mail on a topic beyond the scope of your previous agreement), address this directly in a treatment session.

• File e-mail correspondence, including your reply, in the patient’s medical record.

• Use encryption technology if it is available, practical, and user-friendly.

• Use a practice-dedicated e-mail address with an automatic response that explains when e-mail will be answered and reminds patients to seek immediate help for urgent matters.

Real legal risk

Earlier, we described conceivable legal risks that e-mail might create. But has e-mail caused legal problems for physicians? At least 3 recent published decisions answer: “Yes.” And, remember, only a fraction of legal cases lead to published decisions.

• Huffine v Department of Health17 concerns a psychiatrist who was censured by the Washington state medical quality assurance commission for several boundary crossings, including sending his adolescent patient overly intimate e-mails.

• Wheeler v Kron18 lists a variety of legal claims—intentional infliction of emotional distress, negligent infliction of emotional distress, general negligence, and medical malpractice—that arose from a psychiatrist’s e-mailed concerns about visitation arrangements in a divorcing couple’s custody dispute. Although the court dismissed the last 3 claims, it allowed the intentional infliction of emotional distress claim to proceed.

• Ortegoza v Kho19 includes excerpts of e-mails between a primary care physician and his married patient, with whom the physician had affair that led to a medical malpractice lawsuit.

Bottom Line

Most patients want to e-mail their physicians, and many psychiatrists find e-mail helpful in caring for patients. If you are using e-mail in your practice or are contemplating doing so, get the patient’s permission (preferably in writing), and follow the recommendations and guidelines cited in this article’s references.

Related Resources

• Kane B, Sands DZ. Guidelines for the clinical use of electronic mail with patients. http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/1/104.long.

• Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. Sample email consent and guide to email use. www.psychprogram.com/currentpsychiatry.html.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Some of my patients e-mail me questions about their prescriptions, test results, treatment, appointments, etc. I’m often unsure about the best way to respond. If I use e-mail to communicate with patients, what step(s) should I take to minimize medicolegal risks?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Medicine adopts new communication technologies cautiously. Calling patients seems unremarkable to us now, but it took decades after the invention of the telephone for doctors to feel comfortable talking to patients other than in face-to-face meetings.1,2

Patients want to communicate with their physicians via electronic mail,3 but concerns about security, confidentiality, and liability stop many physicians from using e-mail in their practice. Yet many medical organizations, including the Institute of Medicine,4 the American Medical Association,5 and the American Psychiatric Association,6 recognize that e-mail can facilitate care, if used properly.

Although e-mailing patients may feel awkward, a growing minority of clinicians regularly use e-mail for patient communication.2,7 In this article, we discuss ways to help safeguard your patients and their communications and to protect yourself from legal headaches.8

As you’re reading, please remember that we’re discussing communications to patients through standard e-mail, not secure portals (such as MyChart) that allow patients to contact physicians confidentially through their electronic medical records.

Privacy and security

Doctor-patient e-mails implicate the same professional, ethical, and legal responsibilities that govern any communication with patients.2,9,10 If handled improperly, outside-the-office doctor-patient communication can breach traditional duties to protect confidentiality, or they can violate provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).11 Confidentiality breaches can lead to malpractice litigation, and HIPAA infractions can result in civil and criminal penalties levied by federal agencies.12 Further, e-mails that breach ethical standards (Table 15) can generate complaints to your state’s medical licensure board.

E-mail appeals to many patients, if for no other reason than to save time or avoid the inconvenience of playing “phone tag” with the doctor’s office. But e-mail has drawbacks. Patients may think or behave as though online communications are intimate and confidential, but they usually aren’t. If e-mail programs are left open or aren’t password protected, friends and family members might look at messages and even act upon them. For this reason, doctors often cannot be sure whether they are communicating with the patient or with someone else who has gained access to the patient’s e-mail account.

Parties outside the treatment relationship could have access to e-mail data stored on servers.6 Also, it’s easy to misread or mistype an e-mail address and send confidential information to the wrong person. A truly “secure” e-mail exchange uses encryption software that protects messages during transmission and storage and requires users to authenticate who they are through actions that link their identity to the e-mail address.13 But some patients and physicians do not know about the availability of such security measures, and implementing them can feel cumbersome to those who are not computer savvy. Not surprisingly, then, recent studies have shown that such measures are used infrequently by physicians and patients.14

Topics for e-mail communication

One way to minimize potential privacy problems is to limit the topics and types of communication dealt with by e-mail. Several experts and organizations have published suggestions, recommendations, and resources for doing this with common practices (Table 2).6,7,15

Receiving e-mail permission

Many patients e-mail their physicians without the physicians’ prior agreement. But physicians who plan to use e-mail in their practice should get patients’ explicit consent. This can be done verbally, with the content of the discussion documented in the medical record. But it’s better to have patients authorize e-mail communications in writing by means of a permission form that also sets out your office’s e-mail policies, expected response times, and privacy limitations.

Commonly recommended contents of such forms5-7,9,15,16 include:

• discussing security mechanisms and limits of security

• e-mail encryption requirements (or waiving them, if the patient prefers)

• providing an expected response time

• indemnifying you or your institution for information loss caused by technical failure

• identifying who reads e-mails (eg, office staff members, a nurse, physician [only])

• asking patients to put their name and other identifying information in the body of the message, not the subject line

• asking patients to put the type of question in the subject line (eg, “prescription,” “appointment,” “billing”)

• asking patients to use the “auto reply” feature to acknowledge receipt of your messages.

In addition to using patient consent forms, other suggestions and recommendations for physicians include:

• Do not use e-mail to establish patient-physician relationships, only to supplement personal encounters.

• If you work for an agency or institution, know and follow its guidelines and policies.

• If a rule or “boundary” is breached (eg, a patient sends you a detailed e-mail on a topic beyond the scope of your previous agreement), address this directly in a treatment session.

• File e-mail correspondence, including your reply, in the patient’s medical record.

• Use encryption technology if it is available, practical, and user-friendly.

• Use a practice-dedicated e-mail address with an automatic response that explains when e-mail will be answered and reminds patients to seek immediate help for urgent matters.

Real legal risk

Earlier, we described conceivable legal risks that e-mail might create. But has e-mail caused legal problems for physicians? At least 3 recent published decisions answer: “Yes.” And, remember, only a fraction of legal cases lead to published decisions.

• Huffine v Department of Health17 concerns a psychiatrist who was censured by the Washington state medical quality assurance commission for several boundary crossings, including sending his adolescent patient overly intimate e-mails.

• Wheeler v Kron18 lists a variety of legal claims—intentional infliction of emotional distress, negligent infliction of emotional distress, general negligence, and medical malpractice—that arose from a psychiatrist’s e-mailed concerns about visitation arrangements in a divorcing couple’s custody dispute. Although the court dismissed the last 3 claims, it allowed the intentional infliction of emotional distress claim to proceed.

• Ortegoza v Kho19 includes excerpts of e-mails between a primary care physician and his married patient, with whom the physician had affair that led to a medical malpractice lawsuit.

Bottom Line

Most patients want to e-mail their physicians, and many psychiatrists find e-mail helpful in caring for patients. If you are using e-mail in your practice or are contemplating doing so, get the patient’s permission (preferably in writing), and follow the recommendations and guidelines cited in this article’s references.

Related Resources

• Kane B, Sands DZ. Guidelines for the clinical use of electronic mail with patients. http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/1/104.long.

• Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. Sample email consent and guide to email use. www.psychprogram.com/currentpsychiatry.html.

1. Wieczorek SM. From telegraph to e-mail: preserving the doctor-patient relationship in a high-tech environment. ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 2010;67(3):311-327.

2. Spielberg AR. Online without a net: physician-patient communication by electronic mail. Am J Law Med. 1999;25(2-3):267-295.

3. Pelletier AL, Sutton GR, Walker RR. Are your patients ready for electronic communication? Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(9):25-26.

4. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

5. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Opinion 5.026 - the use of electronic mail. http:// www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/ medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion5026.page. Published June 2013. Accessed March 8, 2015.

6. American Psychiatric Association, Council on Psychiatry & Law. Resource document on telepsychiatry and related technologies in clinical psychiatry. http://www.psychiatry. org/learn/library--archives/resource-documents. Published January 2014. Accessed March 25, 2015.

7. Koh S, Cattell GM, Cochran DM, et al. Psychiatrists’ use of electronic communication and social media and a proposed framework for future guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(3):254-263.

8. Sands DZ. Help for physicians contemplating use of e-mail with patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(4):268-269.

9. Bovi AM; Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association. Ethical guidelines for use of electronic mail between patients and physicians. Am J Bioeth. 2003;3(3):W-IF2.

10. Kuszler PC. A question of duty: common law legal issues resulting from physician response to unsolicited patient email inquiries. J Med Internet Res. 2000;2(3):E17.

11. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164.

12. Vanderpool D. Hippa-should I be worried? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(11-12):51-55.

13. Tjora A, Tran T, Faxvaag A. Privacy vs. usability: a qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences with secure internet communication with their general practitioner. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(2):e15.

14. Menachemi N, Prickett CT, Brooks RG. The use of physician-patient email: a follow-up examination of adoption and best-practice adherence 2005-2008. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e23.

15. Kane B, Sands DZ. Guidelines for the clinical use of electronic mail with patients. The AMIA Internet Working Group, Task Force on guidelines for the use of clinic-patient electronic mail. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(1):104-111.

16. Car J, Sheikh A. Email consultations in health care: 2–acceptability and safe application. BMJ. 2004; 329(7463):439-442.

17. Huffine v Department of Health, 148 Wn App 1015 (Wash Ct App 2009).

18. Wheeler v Akron (NY Misc LEXIS 942, 2011) NY Slip Op 30530(U) (NY Misc 2011).

19. Ortegoza v Kho, 2013 U.S. Dist .LEXIS 69999 (SD Cal 2013).

1. Wieczorek SM. From telegraph to e-mail: preserving the doctor-patient relationship in a high-tech environment. ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 2010;67(3):311-327.

2. Spielberg AR. Online without a net: physician-patient communication by electronic mail. Am J Law Med. 1999;25(2-3):267-295.

3. Pelletier AL, Sutton GR, Walker RR. Are your patients ready for electronic communication? Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(9):25-26.

4. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

5. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Opinion 5.026 - the use of electronic mail. http:// www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/ medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion5026.page. Published June 2013. Accessed March 8, 2015.

6. American Psychiatric Association, Council on Psychiatry & Law. Resource document on telepsychiatry and related technologies in clinical psychiatry. http://www.psychiatry. org/learn/library--archives/resource-documents. Published January 2014. Accessed March 25, 2015.

7. Koh S, Cattell GM, Cochran DM, et al. Psychiatrists’ use of electronic communication and social media and a proposed framework for future guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(3):254-263.

8. Sands DZ. Help for physicians contemplating use of e-mail with patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(4):268-269.

9. Bovi AM; Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association. Ethical guidelines for use of electronic mail between patients and physicians. Am J Bioeth. 2003;3(3):W-IF2.

10. Kuszler PC. A question of duty: common law legal issues resulting from physician response to unsolicited patient email inquiries. J Med Internet Res. 2000;2(3):E17.

11. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164.

12. Vanderpool D. Hippa-should I be worried? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(11-12):51-55.

13. Tjora A, Tran T, Faxvaag A. Privacy vs. usability: a qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences with secure internet communication with their general practitioner. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(2):e15.

14. Menachemi N, Prickett CT, Brooks RG. The use of physician-patient email: a follow-up examination of adoption and best-practice adherence 2005-2008. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e23.

15. Kane B, Sands DZ. Guidelines for the clinical use of electronic mail with patients. The AMIA Internet Working Group, Task Force on guidelines for the use of clinic-patient electronic mail. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(1):104-111.

16. Car J, Sheikh A. Email consultations in health care: 2–acceptability and safe application. BMJ. 2004; 329(7463):439-442.

17. Huffine v Department of Health, 148 Wn App 1015 (Wash Ct App 2009).

18. Wheeler v Akron (NY Misc LEXIS 942, 2011) NY Slip Op 30530(U) (NY Misc 2011).

19. Ortegoza v Kho, 2013 U.S. Dist .LEXIS 69999 (SD Cal 2013).

Good, bad, and ugly: Prior authorization and medicolegal risk

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

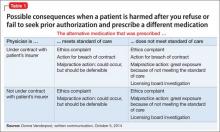

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

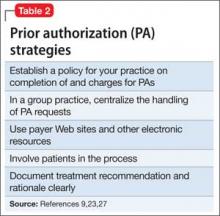

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?

Some practitioners charge patients for time spent completing PAs.23 Although physicians should “complete without charge the appropriate ‘simplified’ insurance claim form as a part of service to the patient;” they also may consider “a charge for more complex or multiple forms … in conformity with local custom.”24 Legally, physicians’ contracts with insurance panels may preclude charging such fees, but if a patient is being seen out of network, the physician does not have a contractual obligation and may charge.9 If your practice setting lets you choose which insurances you accept, the impact and burden of seeking PAs is a factor to consider when deciding whether to participate in a particular panel.23

In an interesting twist, an Ohio physician successfully sued a medical insurance administrator for the cost of his time responding to PA inquiries.25 Reasoning that the insurance administrator “should expect to pay for the reasonable value of” the doctor’s time because the PAs “were solely intended for the benefit of the insurance administrator” or parties whom the administrator served, the judge awarded the doctor $187.50 plus 8% interest.

Considerations that are more practical relate to how to triage and address the volume of PA requests. Some large medical practices centralize PAs and try to set up pre-approved plans of care or blanket approvals for frequently encountered conditions. Centralization also allows one key administrative assistant to develop skills in processing PA requests and to build relationships with payers.26

The administrative assistant also can compile lists of preferred alternative medications, PA forms, and payer Web sites. Using and submitting requests through payer Web sites can speed up PA processing, which saves time and money.27 As electronic health records improve, they may incorporate patients’ formularies and provide automatic alerts for required PAs.23

Patients should be involved, too. They can help to obtain relevant formulary information and to weigh alternative therapies. You can help them understand your role in the PA process, the reasoning behind your treatment recommendations, and the delays in picking up prescribed medications that waiting for PA approval can create.

It’s easy to get angry about PAs

Your best response, however, is to practice prudent and—within reason— cost-effective medicine. When generic or insurer-preferred medications are clinically appropriate and meet treatment guidelines, trying them first is sensible and defensible. If your patient fails the initial low-cost treatment, or if a low-cost choice isn’t appropriate, document this clearly and seek approval for a costlier treatment.9

BOTTOM LINE

Physicians have ethical and legal obligations to advocate for their patients’ needs and best interests. This sometimes includes completing prior authorization requests. Find strategies that minimize hassle and make sense in your practice, and seek efficient ways to document the medical necessity of requested tests, procedures, or therapies.

Acknowledgment

Drs. Marett and Mossman thanks Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, and Annette Reynolds, MD, for their helpful input in preparing this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Brown CM, Richards K, Rascati KL, et al. Effects of a psychotherapeutic drug prior authorization (PA) requirement on patients and providers: a providers’ perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(3):181-188.

2. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):540-546.

3. Stein BD, Leckman-Westin E, Okeke E, et al. The effects of prior authorization policies on Medicaid-enrolled children’s use of antipsychotic medications: evidence from two Mid-Atlantic states. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):374-381.

4. Adams KT. Prior authorization–still used, still an issue. Biotechnol Healthc. 2010;7(4):28.

5. Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, et al. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state Medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(5):447-454.

6. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, et al. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence [published online July 9, 2014]. Health Serv Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201.

7. Dunn RL, Harrison D, Ripley TL. The beers criteria as an outpatient screening tool for potentially inappropriate medications. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(10):754-763.

8. Lennertz MD, Wertheimer AI. Is prior authorization for prescribed drugs cost-effective? Drug Benefit Trends. 2008;20:136-139.

9. Bendix J. The prior authorization predicament. Med Econ. 2014;91(13)29-30,32,34-35.

10. Farley JF, Cline RR, Schommer JC, et al. Retrospective assessment of Medicaid step-therapy prior authorization policy for atypical antipsychotic medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1524-1539; discussion 1506-1507.

11. Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(5):247-254.

12. Brown CM, Nwokeji E, Rascati KL, et al. Development of the burden of prior authorization of psychotherapeutics (BoPAP) scale to assess the effects of prior authorization among Texas Medicaid providers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):278-287.

13. Rascati KL, Brown CM. Prior authorization for antipsychotic medications—It’s not just about the money. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1506-1507.

14. Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar disorder. Med Care. 2010;48(1):4-9.

15. Stephens RJ, White SE, Cudnik M, et al. Factors associated with longer lengths of stay for mental health emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47(4):412-419.

16. Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):878-885.

17. American Medical Association. Opinion 10.01– Fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/ physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page?. Accessed October 11, 2014.

18. Hall RC. Ethical and legal implications of managed care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(3):200-208.

19. Porter v Thadani, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35145 (NH 2010).

20. NB ex rel Peacock v District of Columbia, 682 F3d 77 (DC Cir 2012).

21. Wilson v Blue Cross of Southern California, 222 Cal App 3d 660, 271 Cal Rptr 876 (1990).

22. Wickline v State of California, 192 Cal App 3d 1630, 239 Cal Rptr 810 (1986).

23. Terry K. Prior authorization made easier. Med Econ. 2007;84(20):34,38,40.

24. American Medical Association. Ethics Opinion 6.07– Insurance forms completion charges. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion607.page? Updated June 1994. Accessed October 11, 2014.

25. Gibson v Medco Health Solutions, 06-CVF-106 (OH 2008).

26. Bendix J. Curing the prior authorization headache. Med Econ. 2013;90(19):24,26-27,29-31.

27. American Medical Association. Electronic prior authorization toolkit. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/administrative-simplification-initiatives/electronic-transactions-toolkit/ prior-authorization.page. Accessed October 11, 2014.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?

Some practitioners charge patients for time spent completing PAs.23 Although physicians should “complete without charge the appropriate ‘simplified’ insurance claim form as a part of service to the patient;” they also may consider “a charge for more complex or multiple forms … in conformity with local custom.”24 Legally, physicians’ contracts with insurance panels may preclude charging such fees, but if a patient is being seen out of network, the physician does not have a contractual obligation and may charge.9 If your practice setting lets you choose which insurances you accept, the impact and burden of seeking PAs is a factor to consider when deciding whether to participate in a particular panel.23

In an interesting twist, an Ohio physician successfully sued a medical insurance administrator for the cost of his time responding to PA inquiries.25 Reasoning that the insurance administrator “should expect to pay for the reasonable value of” the doctor’s time because the PAs “were solely intended for the benefit of the insurance administrator” or parties whom the administrator served, the judge awarded the doctor $187.50 plus 8% interest.

Considerations that are more practical relate to how to triage and address the volume of PA requests. Some large medical practices centralize PAs and try to set up pre-approved plans of care or blanket approvals for frequently encountered conditions. Centralization also allows one key administrative assistant to develop skills in processing PA requests and to build relationships with payers.26

The administrative assistant also can compile lists of preferred alternative medications, PA forms, and payer Web sites. Using and submitting requests through payer Web sites can speed up PA processing, which saves time and money.27 As electronic health records improve, they may incorporate patients’ formularies and provide automatic alerts for required PAs.23

Patients should be involved, too. They can help to obtain relevant formulary information and to weigh alternative therapies. You can help them understand your role in the PA process, the reasoning behind your treatment recommendations, and the delays in picking up prescribed medications that waiting for PA approval can create.

It’s easy to get angry about PAs

Your best response, however, is to practice prudent and—within reason— cost-effective medicine. When generic or insurer-preferred medications are clinically appropriate and meet treatment guidelines, trying them first is sensible and defensible. If your patient fails the initial low-cost treatment, or if a low-cost choice isn’t appropriate, document this clearly and seek approval for a costlier treatment.9

BOTTOM LINE

Physicians have ethical and legal obligations to advocate for their patients’ needs and best interests. This sometimes includes completing prior authorization requests. Find strategies that minimize hassle and make sense in your practice, and seek efficient ways to document the medical necessity of requested tests, procedures, or therapies.

Acknowledgment

Drs. Marett and Mossman thanks Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, and Annette Reynolds, MD, for their helpful input in preparing this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?

Some practitioners charge patients for time spent completing PAs.23 Although physicians should “complete without charge the appropriate ‘simplified’ insurance claim form as a part of service to the patient;” they also may consider “a charge for more complex or multiple forms … in conformity with local custom.”24 Legally, physicians’ contracts with insurance panels may preclude charging such fees, but if a patient is being seen out of network, the physician does not have a contractual obligation and may charge.9 If your practice setting lets you choose which insurances you accept, the impact and burden of seeking PAs is a factor to consider when deciding whether to participate in a particular panel.23

In an interesting twist, an Ohio physician successfully sued a medical insurance administrator for the cost of his time responding to PA inquiries.25 Reasoning that the insurance administrator “should expect to pay for the reasonable value of” the doctor’s time because the PAs “were solely intended for the benefit of the insurance administrator” or parties whom the administrator served, the judge awarded the doctor $187.50 plus 8% interest.

Considerations that are more practical relate to how to triage and address the volume of PA requests. Some large medical practices centralize PAs and try to set up pre-approved plans of care or blanket approvals for frequently encountered conditions. Centralization also allows one key administrative assistant to develop skills in processing PA requests and to build relationships with payers.26

The administrative assistant also can compile lists of preferred alternative medications, PA forms, and payer Web sites. Using and submitting requests through payer Web sites can speed up PA processing, which saves time and money.27 As electronic health records improve, they may incorporate patients’ formularies and provide automatic alerts for required PAs.23

Patients should be involved, too. They can help to obtain relevant formulary information and to weigh alternative therapies. You can help them understand your role in the PA process, the reasoning behind your treatment recommendations, and the delays in picking up prescribed medications that waiting for PA approval can create.

It’s easy to get angry about PAs

Your best response, however, is to practice prudent and—within reason— cost-effective medicine. When generic or insurer-preferred medications are clinically appropriate and meet treatment guidelines, trying them first is sensible and defensible. If your patient fails the initial low-cost treatment, or if a low-cost choice isn’t appropriate, document this clearly and seek approval for a costlier treatment.9

BOTTOM LINE

Physicians have ethical and legal obligations to advocate for their patients’ needs and best interests. This sometimes includes completing prior authorization requests. Find strategies that minimize hassle and make sense in your practice, and seek efficient ways to document the medical necessity of requested tests, procedures, or therapies.

Acknowledgment

Drs. Marett and Mossman thanks Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, and Annette Reynolds, MD, for their helpful input in preparing this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Brown CM, Richards K, Rascati KL, et al. Effects of a psychotherapeutic drug prior authorization (PA) requirement on patients and providers: a providers’ perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(3):181-188.

2. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):540-546.

3. Stein BD, Leckman-Westin E, Okeke E, et al. The effects of prior authorization policies on Medicaid-enrolled children’s use of antipsychotic medications: evidence from two Mid-Atlantic states. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):374-381.

4. Adams KT. Prior authorization–still used, still an issue. Biotechnol Healthc. 2010;7(4):28.

5. Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, et al. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state Medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(5):447-454.

6. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, et al. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence [published online July 9, 2014]. Health Serv Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201.

7. Dunn RL, Harrison D, Ripley TL. The beers criteria as an outpatient screening tool for potentially inappropriate medications. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(10):754-763.

8. Lennertz MD, Wertheimer AI. Is prior authorization for prescribed drugs cost-effective? Drug Benefit Trends. 2008;20:136-139.

9. Bendix J. The prior authorization predicament. Med Econ. 2014;91(13)29-30,32,34-35.

10. Farley JF, Cline RR, Schommer JC, et al. Retrospective assessment of Medicaid step-therapy prior authorization policy for atypical antipsychotic medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1524-1539; discussion 1506-1507.

11. Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(5):247-254.

12. Brown CM, Nwokeji E, Rascati KL, et al. Development of the burden of prior authorization of psychotherapeutics (BoPAP) scale to assess the effects of prior authorization among Texas Medicaid providers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):278-287.

13. Rascati KL, Brown CM. Prior authorization for antipsychotic medications—It’s not just about the money. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1506-1507.

14. Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar disorder. Med Care. 2010;48(1):4-9.

15. Stephens RJ, White SE, Cudnik M, et al. Factors associated with longer lengths of stay for mental health emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47(4):412-419.

16. Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):878-885.

17. American Medical Association. Opinion 10.01– Fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/ physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page?. Accessed October 11, 2014.

18. Hall RC. Ethical and legal implications of managed care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(3):200-208.

19. Porter v Thadani, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35145 (NH 2010).

20. NB ex rel Peacock v District of Columbia, 682 F3d 77 (DC Cir 2012).

21. Wilson v Blue Cross of Southern California, 222 Cal App 3d 660, 271 Cal Rptr 876 (1990).

22. Wickline v State of California, 192 Cal App 3d 1630, 239 Cal Rptr 810 (1986).

23. Terry K. Prior authorization made easier. Med Econ. 2007;84(20):34,38,40.

24. American Medical Association. Ethics Opinion 6.07– Insurance forms completion charges. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion607.page? Updated June 1994. Accessed October 11, 2014.

25. Gibson v Medco Health Solutions, 06-CVF-106 (OH 2008).

26. Bendix J. Curing the prior authorization headache. Med Econ. 2013;90(19):24,26-27,29-31.

27. American Medical Association. Electronic prior authorization toolkit. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/administrative-simplification-initiatives/electronic-transactions-toolkit/ prior-authorization.page. Accessed October 11, 2014.

1. Brown CM, Richards K, Rascati KL, et al. Effects of a psychotherapeutic drug prior authorization (PA) requirement on patients and providers: a providers’ perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(3):181-188.

2. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):540-546.

3. Stein BD, Leckman-Westin E, Okeke E, et al. The effects of prior authorization policies on Medicaid-enrolled children’s use of antipsychotic medications: evidence from two Mid-Atlantic states. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):374-381.

4. Adams KT. Prior authorization–still used, still an issue. Biotechnol Healthc. 2010;7(4):28.

5. Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, et al. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state Medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(5):447-454.

6. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, et al. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence [published online July 9, 2014]. Health Serv Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201.

7. Dunn RL, Harrison D, Ripley TL. The beers criteria as an outpatient screening tool for potentially inappropriate medications. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(10):754-763.

8. Lennertz MD, Wertheimer AI. Is prior authorization for prescribed drugs cost-effective? Drug Benefit Trends. 2008;20:136-139.

9. Bendix J. The prior authorization predicament. Med Econ. 2014;91(13)29-30,32,34-35.

10. Farley JF, Cline RR, Schommer JC, et al. Retrospective assessment of Medicaid step-therapy prior authorization policy for atypical antipsychotic medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1524-1539; discussion 1506-1507.

11. Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(5):247-254.

12. Brown CM, Nwokeji E, Rascati KL, et al. Development of the burden of prior authorization of psychotherapeutics (BoPAP) scale to assess the effects of prior authorization among Texas Medicaid providers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):278-287.

13. Rascati KL, Brown CM. Prior authorization for antipsychotic medications—It’s not just about the money. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1506-1507.

14. Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar disorder. Med Care. 2010;48(1):4-9.

15. Stephens RJ, White SE, Cudnik M, et al. Factors associated with longer lengths of stay for mental health emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47(4):412-419.

16. Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):878-885.

17. American Medical Association. Opinion 10.01– Fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/ physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page?. Accessed October 11, 2014.

18. Hall RC. Ethical and legal implications of managed care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(3):200-208.

19. Porter v Thadani, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35145 (NH 2010).

20. NB ex rel Peacock v District of Columbia, 682 F3d 77 (DC Cir 2012).

21. Wilson v Blue Cross of Southern California, 222 Cal App 3d 660, 271 Cal Rptr 876 (1990).

22. Wickline v State of California, 192 Cal App 3d 1630, 239 Cal Rptr 810 (1986).

23. Terry K. Prior authorization made easier. Med Econ. 2007;84(20):34,38,40.

24. American Medical Association. Ethics Opinion 6.07– Insurance forms completion charges. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion607.page? Updated June 1994. Accessed October 11, 2014.

25. Gibson v Medco Health Solutions, 06-CVF-106 (OH 2008).

26. Bendix J. Curing the prior authorization headache. Med Econ. 2013;90(19):24,26-27,29-31.

27. American Medical Association. Electronic prior authorization toolkit. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/administrative-simplification-initiatives/electronic-transactions-toolkit/ prior-authorization.page. Accessed October 11, 2014.

What makes you responsible during a screening call?

What are your responsibilities after a screening call?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

When I take a call from a treatment-seeker at our outpatient clinic, I ask brief screening questions to determine whether our services would be appropriate. Shortly after I screened one caller, Ms. C, she called back requesting a medication refill and asking about her diagnosis.

What obligation do I have to Ms. C? Is she my patient? Would I be liable if I didn’t help her out and something bad happened to her?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Office and hospital Web sites, LinkedIn profiles, and Facebook pages are just a few of the ways that people find physicians and learn about their services. But most 21st century doctor-patient relationships still start with 19th century technology: a telephone call.

Talking with prospective patients before setting up an appointment makes sense. A short conversation can clarify whether you offer the services that a caller needs and increases the show-up rate for initial appointments.1

But if you ask for some personal history and information about symptoms in a screening interview, does that make the caller your patient? Ms. C seemed to have thought so. To find out whether Ms. C was right and to learn how Dr. S should handle initial telephone calls, we’ll look at:

• the rationale for screening callers before initiating treatment

• features of screening that can create a doctor-patient relationship

• how to fulfill duties that result from screening.

Why screen prospective patients?

Mental health treatment has become more diversified and specialized over the past 30 years. No psychiatrist nowadays has all the therapeutic skills that all potential patients might need.

Before speaking to you, a treatment-seeker often won’t know whether your practice style will fit his (her) needs. You might prefer not to provide medication management for another clinician’s psychotherapy patient or, if you’re like most psychiatrists, you might not offer psychotherapy.

In the absence of prior obligation (eg, agreeing to provide coverage for an emergency room), physicians may structure their practices and contract for their services as they see fit2—but this leaves you with some obligation to screen potential patients for appropriate mutual fit. In years past, some psychiatrists saw potential patients for an in-office evaluation to decide whether to provide treatment—a practicethat remains acceptable if the person is told, when the appointment is made, that the first meeting is “to meet each other and see if you want to establish a treatment relationship.”3

Good treatment plans take into account patients’ temperament, emotional state, cognitive capacity, culture, family circumstances, substance use, and medical history.4 Common mental conditions often can be identified in a telephone call.5,6 Although the diagnostic accuracy of such efforts is uncertain,7 such calls can help practitioners determine whether they offer the right services for callers. Good decisions about initiating care always take financial pressures and constraints into account,8 and a pre-appointment telephone call can address those issues, too.

For all these reasons, talking to a prospective patient before he comes to see you makes sense. Screening lets you decide:

• whether you’re the right clinician for his needs

• who the right clinician is if you are not

• whether he should seek emergency evaluation when the situation sounds urgent.

Do phone calls start treatment?

As Dr. S’s questions show, telephone screenings might leave some callers thinking that treatment has started, even before their first office appointment. Having a treatment relationship is a prerequisite to malpractice liability,9 and courts have concluded that, under the right circumstances, telephone assessments do create physician-patient relationships.

Creating a physician-patient relationship