User login

Dear Dr. Mossman:

My patient, Ms. X, returned to see me after she had spent 3 months in jail. When I accessed her medication history in our state’s prescription registry, I discovered that, during her incarceration, a local pharmacy continued to fill her prescription for clonazepam. After anxiously explaining that her roommate had filled the prescriptions, Ms. X pleaded with me not to tell anyone. Do I have to report this to legal authorities? If I do, will I be breaching confidentiality?

Submitted by Dr. L

Preserving the confidentiality of patient encounters is an ethical responsibility as old as the Hippocratic Oath,1 but protecting privacy is not an absolute duty. As psychiatrists familiar with the Tarasoff case2 know, clinical events sometimes create moral and legal obligations that outweigh our confidentiality obligations.

What Dr. L should do may hinge on specific details of Ms. X’s previous and current treatment, but in this article, we’ll examine some general issues that affect Dr. L’s choices. These include:

• reporting a past crime

• liability risks associated with violating confidentiality.

Monitoring controlled substances

Dr. L’s clinical situation probably would not have arisen 10 years ago because until recently, she would have had no easy way to learn that Ms. X’s prescription had been filled. In 2002, Congress responded to increasing concern about “epidemic” abuse of controlled substances—especially opioids—by authorizing state grants for prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).3

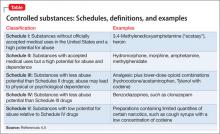

PDMPs are internet-based registries that let physicians quickly find out when and where their patients have filled prescriptions for controlled substances (defined in the Table).4,5 As the rate of opioid-related deaths has risen,6 at least 43 states have initiated PDMPs; soon, all U.S. jurisdictions likely will have such programs.7 Data about the impact of PDMPs, although limited, suggest that PDMPs reduce “doctor shopping” and prescription drug abuse.8

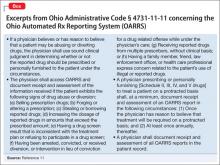

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is promoting the development of electronic architecture standards to facilitate information exchange across jurisdictions,9 but states currently run their own PDMPs independently and have varying regulations about how physicians should use PDMPs.10 Excerpts from the rules used in Ohio’s prescription reporting system appear in the Box.11

Reporting past crimes

What Ms. X told Dr. L implies that someone—the patient, her roommate, or both—misused a prescription to obtain a controlled substance. Simple improper possession of a scheduled drug is a federal misdemeanor offense,12 and deception and conspiracy to obtain a scheduled drug are federal-level felonies.13 Such actions also violate state laws. Dr. L therefore knows that a crime has occurred.

Are doctors obligated or legally required to breach confidentiality and tell authorities about a patient’s past criminal acts? Writing several years ago, Appelbaum and Meisel14 and Goldman and Gutheil15 said the answer, in general, is “no.”

In recent years, state legislatures have modified criminal codes to encourage people to disclose their knowledge of certain crimes to police. For example, failures to report environmental offenses and financial misdealings have become criminal acts.16 A minority of states now punish failure to report other kinds of illegal behavior, but these laws focus mainly on violent crimes (often involving harm to vulnerable persons).17 Although Ohio has a law that obligates everyone to report knowledge of any felony, it makes exceptions when the information is learned during a customarily confidential relationship—including a physician’s treatment of a patient.18 Unless Dr. L herself has aided or concealed a crime (both illegal acts19), concerns about possible prosecution should not affect her decision to report what she has learned thus far.14

Deciding how to proceed

If Dr. L still feels inclined to do something about the misused prescription, what are her options? What clinical, legal, and moral obligations to act should she consider?

Obtain the facts. First, Dr. L should try to learn more about what happened. Jails are reluctant to give inmates benzodiazepines20; did Ms. X receive clonazepam while in jail? When and how did Ms. X learn about her roommate’s actions? Did Ms. X obtain previous prescriptions from Dr. L with the intention of letting her roommate use them? Answers to these questions can help Dr. L determine whether her patient participated in prescription misuse, an important factor in deciding what clinical or legal actions to take.

Should the patient take the lead? Learning more about the situation might suggest that Ms. X should report what has happened herself. If, for example, the roommate has coerced Ms. X to engage in illegal conduct, Dr. L might help Ms. X figure out how to tell police what has happened—preferably after Ms. X has obtained legal advice.14

Consider implications for treatment. Last, what Ms. X reveals might significantly alter her future interactions with Dr. L. This is particularly true if Dr. L concluded that Ms. X would likely divert drugs in the future, or that the patient had established her relationship with Dr. L for purposes of improperly obtaining drugs. Federal regulations require that doctors prescribe drugs only for “legitimate medical purposes,” and issuing prescriptions to a patient who is known to be delivering the drugs to others violates this law.22

Bottom Line

Growing concern about prescription drug misuse has led to nationwide implementation of systems for monitoring patients’ access to, and receipt of, controlled substances. Psychiatrists are expected to be more vigilant about patients’ use of scheduled drugs and, when they believe that a prescription has been misused, to take appropriate clinical or legal action.

Related Resources

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/issues-content/ prescription-drugs/rx_abuse_plan.pdf.

- California Department of Alcohol and Drug Misuse. Preventing prescription drug misuse. www.prescriptiondrugmisuse.org.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Combating misuse and abuse of prescription drugs: Q&A with Michael Klein, PhD. www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ ucm220112.htm.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin Hydromorphone • Dilaudid

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. von Staden H. “In a pure and holy way”: personal and professional conduct in the Hippocratic Oath? J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1996;51(4):404-437.

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 17 Cal.3d 425, 551 P.2d 334, 131 Cal Rptr 14 (Cal 1976).

3. PubLNo.107-177,115Stat748.

4. ControlledSubstancesAct,21USC§812(b)(2007).

5. Schedules of Controlled Substances, 21 CFR. § 1308.11– 1308.15 (2013).

6. Dowell D, Kunins HV, Farley TA. Opioid analgesics— risky drugs, not risky patients. JAMA. 2013;309: 2219-2220.

7. US Department of Justice. Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program FY 2013 Competitive Grant Announcement. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs; 2013. OMB No. 1121-0329.

8. Worley J. Prescription drug monitoring programs, a response to doctor shopping: purpose, effectiveness, and directions for future research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33:319-328.

9. PubLNo.112-144,126Stat993.

10. Finklea KM, Bagalman E, Sacco L. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service; 2013. Report No. R42593.

11. Ohio State Medical Association. 4731-11-11 Standards and procedures for review of Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS). http://www.osma.org/files/pdf/sept- 2011-draft-4731-11-11-ph-of-n-ru-20110520-1541.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2013.

12. Prohibited Acts C, 21 USC §843(a)(3) (2007).

13. PenaltyforSimplePossession,21USC§844(a)(2007).

14. Appelbaum PS, Meisel A. Therapists’ obligations to report their patients’ criminal acts. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1986;14(3):221-230.

15. Goldman MJ, Gutheil TG. The misperceived duty to report patients’ past crimes. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1994; 22(3):407-410.

16. Thompson SG. The white-collar police force: “duty to report” statutes in criminal law theory. William Mary Bill Rights J. 2002;11(1):3-65.

17. Trombley B. No stitches for snitches: the need for a duty-to-report law in Arkansas. Univ Ark Little Rock Law J. 2012; 34:813-832.

18. OhioRevisedCode§2921.22.

19. Section2:Principals,18USC§2(a).

20. Reeves R. Guideline, education, and peer comparison to reduce prescriptions of benzodiazepines and low-dose quetiapine in prison. J Correct Health Care. 2012;18(1): 45-52.

21. Appelbaum PS. Suits against clinicians for warning of patients’ violence. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(7):683-684.

22. UnitedStatesvRosen,582F2d1032(5thCir1978).

23. State Medical Board of Ohio. Regarding the duty of a physician to report criminal behavior to law enforcement. http://www.med.ohio.gov/pdf/NEWS/Duty%20to%20Report_March%202013.pdf. Adopted March 2013. Accessed July 1, 2013.

24. Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. Preventing Prescription Fraud. http://health.mo.gov/ safety/bndd/publications.php. Accessed July 1, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

My patient, Ms. X, returned to see me after she had spent 3 months in jail. When I accessed her medication history in our state’s prescription registry, I discovered that, during her incarceration, a local pharmacy continued to fill her prescription for clonazepam. After anxiously explaining that her roommate had filled the prescriptions, Ms. X pleaded with me not to tell anyone. Do I have to report this to legal authorities? If I do, will I be breaching confidentiality?

Submitted by Dr. L

Preserving the confidentiality of patient encounters is an ethical responsibility as old as the Hippocratic Oath,1 but protecting privacy is not an absolute duty. As psychiatrists familiar with the Tarasoff case2 know, clinical events sometimes create moral and legal obligations that outweigh our confidentiality obligations.

What Dr. L should do may hinge on specific details of Ms. X’s previous and current treatment, but in this article, we’ll examine some general issues that affect Dr. L’s choices. These include:

• reporting a past crime

• liability risks associated with violating confidentiality.

Monitoring controlled substances

Dr. L’s clinical situation probably would not have arisen 10 years ago because until recently, she would have had no easy way to learn that Ms. X’s prescription had been filled. In 2002, Congress responded to increasing concern about “epidemic” abuse of controlled substances—especially opioids—by authorizing state grants for prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).3

PDMPs are internet-based registries that let physicians quickly find out when and where their patients have filled prescriptions for controlled substances (defined in the Table).4,5 As the rate of opioid-related deaths has risen,6 at least 43 states have initiated PDMPs; soon, all U.S. jurisdictions likely will have such programs.7 Data about the impact of PDMPs, although limited, suggest that PDMPs reduce “doctor shopping” and prescription drug abuse.8

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is promoting the development of electronic architecture standards to facilitate information exchange across jurisdictions,9 but states currently run their own PDMPs independently and have varying regulations about how physicians should use PDMPs.10 Excerpts from the rules used in Ohio’s prescription reporting system appear in the Box.11

Reporting past crimes

What Ms. X told Dr. L implies that someone—the patient, her roommate, or both—misused a prescription to obtain a controlled substance. Simple improper possession of a scheduled drug is a federal misdemeanor offense,12 and deception and conspiracy to obtain a scheduled drug are federal-level felonies.13 Such actions also violate state laws. Dr. L therefore knows that a crime has occurred.

Are doctors obligated or legally required to breach confidentiality and tell authorities about a patient’s past criminal acts? Writing several years ago, Appelbaum and Meisel14 and Goldman and Gutheil15 said the answer, in general, is “no.”

In recent years, state legislatures have modified criminal codes to encourage people to disclose their knowledge of certain crimes to police. For example, failures to report environmental offenses and financial misdealings have become criminal acts.16 A minority of states now punish failure to report other kinds of illegal behavior, but these laws focus mainly on violent crimes (often involving harm to vulnerable persons).17 Although Ohio has a law that obligates everyone to report knowledge of any felony, it makes exceptions when the information is learned during a customarily confidential relationship—including a physician’s treatment of a patient.18 Unless Dr. L herself has aided or concealed a crime (both illegal acts19), concerns about possible prosecution should not affect her decision to report what she has learned thus far.14

Deciding how to proceed

If Dr. L still feels inclined to do something about the misused prescription, what are her options? What clinical, legal, and moral obligations to act should she consider?

Obtain the facts. First, Dr. L should try to learn more about what happened. Jails are reluctant to give inmates benzodiazepines20; did Ms. X receive clonazepam while in jail? When and how did Ms. X learn about her roommate’s actions? Did Ms. X obtain previous prescriptions from Dr. L with the intention of letting her roommate use them? Answers to these questions can help Dr. L determine whether her patient participated in prescription misuse, an important factor in deciding what clinical or legal actions to take.

Should the patient take the lead? Learning more about the situation might suggest that Ms. X should report what has happened herself. If, for example, the roommate has coerced Ms. X to engage in illegal conduct, Dr. L might help Ms. X figure out how to tell police what has happened—preferably after Ms. X has obtained legal advice.14

Consider implications for treatment. Last, what Ms. X reveals might significantly alter her future interactions with Dr. L. This is particularly true if Dr. L concluded that Ms. X would likely divert drugs in the future, or that the patient had established her relationship with Dr. L for purposes of improperly obtaining drugs. Federal regulations require that doctors prescribe drugs only for “legitimate medical purposes,” and issuing prescriptions to a patient who is known to be delivering the drugs to others violates this law.22

Bottom Line

Growing concern about prescription drug misuse has led to nationwide implementation of systems for monitoring patients’ access to, and receipt of, controlled substances. Psychiatrists are expected to be more vigilant about patients’ use of scheduled drugs and, when they believe that a prescription has been misused, to take appropriate clinical or legal action.

Related Resources

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/issues-content/ prescription-drugs/rx_abuse_plan.pdf.

- California Department of Alcohol and Drug Misuse. Preventing prescription drug misuse. www.prescriptiondrugmisuse.org.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Combating misuse and abuse of prescription drugs: Q&A with Michael Klein, PhD. www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ ucm220112.htm.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin Hydromorphone • Dilaudid

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

My patient, Ms. X, returned to see me after she had spent 3 months in jail. When I accessed her medication history in our state’s prescription registry, I discovered that, during her incarceration, a local pharmacy continued to fill her prescription for clonazepam. After anxiously explaining that her roommate had filled the prescriptions, Ms. X pleaded with me not to tell anyone. Do I have to report this to legal authorities? If I do, will I be breaching confidentiality?

Submitted by Dr. L

Preserving the confidentiality of patient encounters is an ethical responsibility as old as the Hippocratic Oath,1 but protecting privacy is not an absolute duty. As psychiatrists familiar with the Tarasoff case2 know, clinical events sometimes create moral and legal obligations that outweigh our confidentiality obligations.

What Dr. L should do may hinge on specific details of Ms. X’s previous and current treatment, but in this article, we’ll examine some general issues that affect Dr. L’s choices. These include:

• reporting a past crime

• liability risks associated with violating confidentiality.

Monitoring controlled substances

Dr. L’s clinical situation probably would not have arisen 10 years ago because until recently, she would have had no easy way to learn that Ms. X’s prescription had been filled. In 2002, Congress responded to increasing concern about “epidemic” abuse of controlled substances—especially opioids—by authorizing state grants for prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).3

PDMPs are internet-based registries that let physicians quickly find out when and where their patients have filled prescriptions for controlled substances (defined in the Table).4,5 As the rate of opioid-related deaths has risen,6 at least 43 states have initiated PDMPs; soon, all U.S. jurisdictions likely will have such programs.7 Data about the impact of PDMPs, although limited, suggest that PDMPs reduce “doctor shopping” and prescription drug abuse.8

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is promoting the development of electronic architecture standards to facilitate information exchange across jurisdictions,9 but states currently run their own PDMPs independently and have varying regulations about how physicians should use PDMPs.10 Excerpts from the rules used in Ohio’s prescription reporting system appear in the Box.11

Reporting past crimes

What Ms. X told Dr. L implies that someone—the patient, her roommate, or both—misused a prescription to obtain a controlled substance. Simple improper possession of a scheduled drug is a federal misdemeanor offense,12 and deception and conspiracy to obtain a scheduled drug are federal-level felonies.13 Such actions also violate state laws. Dr. L therefore knows that a crime has occurred.

Are doctors obligated or legally required to breach confidentiality and tell authorities about a patient’s past criminal acts? Writing several years ago, Appelbaum and Meisel14 and Goldman and Gutheil15 said the answer, in general, is “no.”

In recent years, state legislatures have modified criminal codes to encourage people to disclose their knowledge of certain crimes to police. For example, failures to report environmental offenses and financial misdealings have become criminal acts.16 A minority of states now punish failure to report other kinds of illegal behavior, but these laws focus mainly on violent crimes (often involving harm to vulnerable persons).17 Although Ohio has a law that obligates everyone to report knowledge of any felony, it makes exceptions when the information is learned during a customarily confidential relationship—including a physician’s treatment of a patient.18 Unless Dr. L herself has aided or concealed a crime (both illegal acts19), concerns about possible prosecution should not affect her decision to report what she has learned thus far.14

Deciding how to proceed

If Dr. L still feels inclined to do something about the misused prescription, what are her options? What clinical, legal, and moral obligations to act should she consider?

Obtain the facts. First, Dr. L should try to learn more about what happened. Jails are reluctant to give inmates benzodiazepines20; did Ms. X receive clonazepam while in jail? When and how did Ms. X learn about her roommate’s actions? Did Ms. X obtain previous prescriptions from Dr. L with the intention of letting her roommate use them? Answers to these questions can help Dr. L determine whether her patient participated in prescription misuse, an important factor in deciding what clinical or legal actions to take.

Should the patient take the lead? Learning more about the situation might suggest that Ms. X should report what has happened herself. If, for example, the roommate has coerced Ms. X to engage in illegal conduct, Dr. L might help Ms. X figure out how to tell police what has happened—preferably after Ms. X has obtained legal advice.14

Consider implications for treatment. Last, what Ms. X reveals might significantly alter her future interactions with Dr. L. This is particularly true if Dr. L concluded that Ms. X would likely divert drugs in the future, or that the patient had established her relationship with Dr. L for purposes of improperly obtaining drugs. Federal regulations require that doctors prescribe drugs only for “legitimate medical purposes,” and issuing prescriptions to a patient who is known to be delivering the drugs to others violates this law.22

Bottom Line

Growing concern about prescription drug misuse has led to nationwide implementation of systems for monitoring patients’ access to, and receipt of, controlled substances. Psychiatrists are expected to be more vigilant about patients’ use of scheduled drugs and, when they believe that a prescription has been misused, to take appropriate clinical or legal action.

Related Resources

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/issues-content/ prescription-drugs/rx_abuse_plan.pdf.

- California Department of Alcohol and Drug Misuse. Preventing prescription drug misuse. www.prescriptiondrugmisuse.org.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Combating misuse and abuse of prescription drugs: Q&A with Michael Klein, PhD. www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ ucm220112.htm.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin Hydromorphone • Dilaudid

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. von Staden H. “In a pure and holy way”: personal and professional conduct in the Hippocratic Oath? J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1996;51(4):404-437.

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 17 Cal.3d 425, 551 P.2d 334, 131 Cal Rptr 14 (Cal 1976).

3. PubLNo.107-177,115Stat748.

4. ControlledSubstancesAct,21USC§812(b)(2007).

5. Schedules of Controlled Substances, 21 CFR. § 1308.11– 1308.15 (2013).

6. Dowell D, Kunins HV, Farley TA. Opioid analgesics— risky drugs, not risky patients. JAMA. 2013;309: 2219-2220.

7. US Department of Justice. Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program FY 2013 Competitive Grant Announcement. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs; 2013. OMB No. 1121-0329.

8. Worley J. Prescription drug monitoring programs, a response to doctor shopping: purpose, effectiveness, and directions for future research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33:319-328.

9. PubLNo.112-144,126Stat993.

10. Finklea KM, Bagalman E, Sacco L. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service; 2013. Report No. R42593.

11. Ohio State Medical Association. 4731-11-11 Standards and procedures for review of Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS). http://www.osma.org/files/pdf/sept- 2011-draft-4731-11-11-ph-of-n-ru-20110520-1541.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2013.

12. Prohibited Acts C, 21 USC §843(a)(3) (2007).

13. PenaltyforSimplePossession,21USC§844(a)(2007).

14. Appelbaum PS, Meisel A. Therapists’ obligations to report their patients’ criminal acts. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1986;14(3):221-230.

15. Goldman MJ, Gutheil TG. The misperceived duty to report patients’ past crimes. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1994; 22(3):407-410.

16. Thompson SG. The white-collar police force: “duty to report” statutes in criminal law theory. William Mary Bill Rights J. 2002;11(1):3-65.

17. Trombley B. No stitches for snitches: the need for a duty-to-report law in Arkansas. Univ Ark Little Rock Law J. 2012; 34:813-832.

18. OhioRevisedCode§2921.22.

19. Section2:Principals,18USC§2(a).

20. Reeves R. Guideline, education, and peer comparison to reduce prescriptions of benzodiazepines and low-dose quetiapine in prison. J Correct Health Care. 2012;18(1): 45-52.

21. Appelbaum PS. Suits against clinicians for warning of patients’ violence. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(7):683-684.

22. UnitedStatesvRosen,582F2d1032(5thCir1978).

23. State Medical Board of Ohio. Regarding the duty of a physician to report criminal behavior to law enforcement. http://www.med.ohio.gov/pdf/NEWS/Duty%20to%20Report_March%202013.pdf. Adopted March 2013. Accessed July 1, 2013.

24. Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. Preventing Prescription Fraud. http://health.mo.gov/ safety/bndd/publications.php. Accessed July 1, 2013.

1. von Staden H. “In a pure and holy way”: personal and professional conduct in the Hippocratic Oath? J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1996;51(4):404-437.

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 17 Cal.3d 425, 551 P.2d 334, 131 Cal Rptr 14 (Cal 1976).

3. PubLNo.107-177,115Stat748.

4. ControlledSubstancesAct,21USC§812(b)(2007).

5. Schedules of Controlled Substances, 21 CFR. § 1308.11– 1308.15 (2013).

6. Dowell D, Kunins HV, Farley TA. Opioid analgesics— risky drugs, not risky patients. JAMA. 2013;309: 2219-2220.

7. US Department of Justice. Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program FY 2013 Competitive Grant Announcement. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs; 2013. OMB No. 1121-0329.

8. Worley J. Prescription drug monitoring programs, a response to doctor shopping: purpose, effectiveness, and directions for future research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33:319-328.

9. PubLNo.112-144,126Stat993.

10. Finklea KM, Bagalman E, Sacco L. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service; 2013. Report No. R42593.

11. Ohio State Medical Association. 4731-11-11 Standards and procedures for review of Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS). http://www.osma.org/files/pdf/sept- 2011-draft-4731-11-11-ph-of-n-ru-20110520-1541.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2013.

12. Prohibited Acts C, 21 USC §843(a)(3) (2007).

13. PenaltyforSimplePossession,21USC§844(a)(2007).

14. Appelbaum PS, Meisel A. Therapists’ obligations to report their patients’ criminal acts. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1986;14(3):221-230.

15. Goldman MJ, Gutheil TG. The misperceived duty to report patients’ past crimes. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1994; 22(3):407-410.

16. Thompson SG. The white-collar police force: “duty to report” statutes in criminal law theory. William Mary Bill Rights J. 2002;11(1):3-65.

17. Trombley B. No stitches for snitches: the need for a duty-to-report law in Arkansas. Univ Ark Little Rock Law J. 2012; 34:813-832.

18. OhioRevisedCode§2921.22.

19. Section2:Principals,18USC§2(a).

20. Reeves R. Guideline, education, and peer comparison to reduce prescriptions of benzodiazepines and low-dose quetiapine in prison. J Correct Health Care. 2012;18(1): 45-52.

21. Appelbaum PS. Suits against clinicians for warning of patients’ violence. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(7):683-684.

22. UnitedStatesvRosen,582F2d1032(5thCir1978).

23. State Medical Board of Ohio. Regarding the duty of a physician to report criminal behavior to law enforcement. http://www.med.ohio.gov/pdf/NEWS/Duty%20to%20Report_March%202013.pdf. Adopted March 2013. Accessed July 1, 2013.

24. Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. Preventing Prescription Fraud. http://health.mo.gov/ safety/bndd/publications.php. Accessed July 1, 2013.