User login

CASE Intervention approaches for decreasing the risk of cervical cancer

A 25-year-old woman presents to your practice for routine examination. She has never undergone cervical cancer screening or received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series. The patient has had 3 lifetime sexual partners and currently uses condoms as contraception. What interventions are appropriate to offer this patient to decrease her risk of cervical cancer? Choose as many that may apply:

1. cervical cytology with reflex HPV testing

2. cervical cytology with HPV cotesting

3. primary HPV testing

4. HPV vaccine series (3 doses)

5. all of the above

The answer is number 5, all of the above.

Choices 1, 2, and 3 are acceptable methods of cervical cancer screening for this patient. Catch-up HPV vaccination should be offered as well.

Equitable preventive care is needed

Cervical cancer is a unique cancer because it has a known preventative strategy. HPV vaccination, paired with cervical screening and management of abnormal results, has contributed to decreased rates of cervical cancer in the United States, from 13,914 cases in 1999 to 12,795 cases in 2019.1 In less-developed countries, however, cervical cancer continues to be a leading cause of mortality, with 90% of cervical cancer deaths in 2020 occurring in low- and middle-income countries.2

Disparate outcomes in cervical cancer are often a reflection of disparities in health access. Within the United States, Black women have a higher incidence of cervical cancer, advanced-stage disease, and mortality from cervical cancer than White women.3,4 Furthermore, the incidence of cervical cancer increased among American Indian and Alaska Native people between 2000 and 2019.5 The rate for patients who are overdue for cervical cancer screening is higher among Asian and Hispanic patients compared with non-Hispanic White patients (31.4% vs 20.1%; P=.01) and among patients who identify as LGBTQ+ compared with patients who identify as heterosexual (32.0% vs 22.2%; P<.001).6 Younger patients have a significantly higher rate for overdue screening compared with their older counterparts (29.1% vs 21.1%; P<.001), as do uninsured patients compared with those who are privately insured (41.7% vs 18.1%; P<.001). Overall, the proportion of women without up-to-date screening increased significantly from 2005 to 2019 (14.4% vs 23.0%; P<.001).6

Unfortunately, despite a known strategy to eliminate cervical cancer, we are not accomplishing equitable preventative care. Barriers to care can include patient-centered issues, such as fear of cancer or of painful evaluations, lack of trust in the health care system, and inadequate understanding of the benefits of cancer prevention, in addition to systemic and structural barriers. As we assess new technologies, one of our most important goals is to consider how such innovations can increase health access—whether through increasing ease and acceptability of testing or by creating more effective screening tests.

Updates to cervical screening guidance

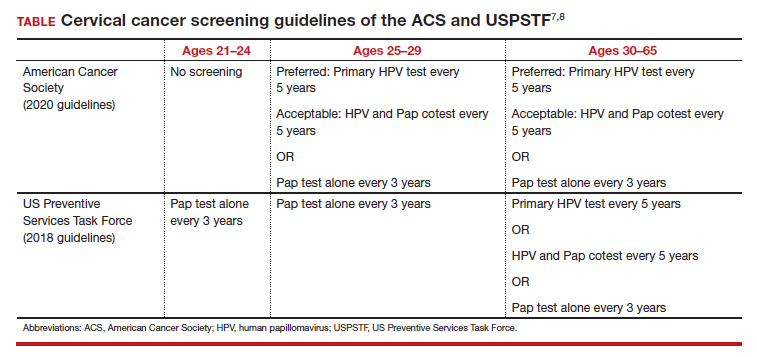

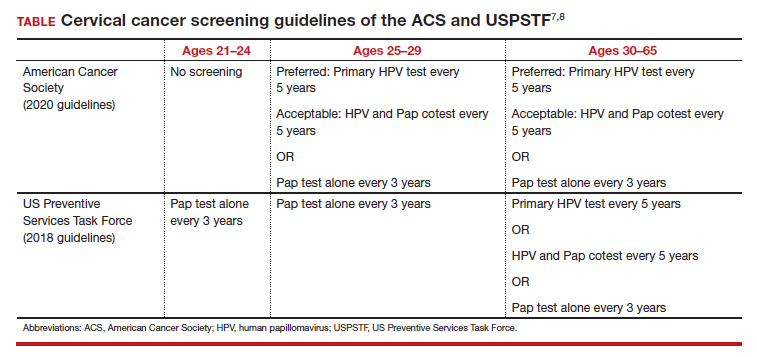

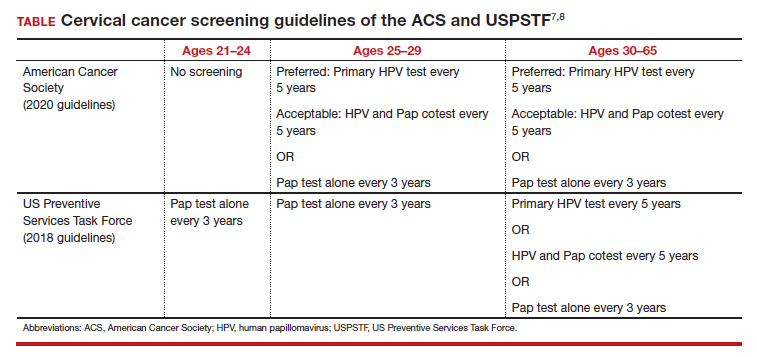

In 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) updated its cervical screening guidelines to start screening at age 25 years with the “preferred” strategy of HPV primary testing every 5 years.7 By contrast, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) continues to recommend 1 of 3 methods: cytology alone every 3 years; cytology alone every 3 years between ages 21 and 29 followed by cytology and HPV cotesting every 5 years at age 30 or older; or high-risk HPV testing alone every 5 years (TABLE).8

To successfully prevent cervical cancer, abnormal results are managed by performing either colposcopy with biopsy, immediate treatment, or close surveillance based on the risk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3 or worse. A patient’s risk is determined based on both current and prior test results. The ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) transitioned to risk-based management guidelines in 2019 and has both an app and a web-based risk assessment tool available for clinicians (https://www.asccp.org).9

All organizations recommend stopping screening after age 65 provided there has been a history of adequate screening in the prior 10 years (defined as 2 normal cotests or 3 normal cytology tests, with the most recent test within 5 years) and no history of CIN 2 or worse within the prior 25 years.10,11 Recent studies that examined the rate of cervical cancer diagnosed in patients older than 65 years have questioned whether patients should continue screening beyond 65.10 In the United States, 20% of cervical cancer still occurs in women older than age 65.11 One reason may be that many women have not met the requirement for adequate and normal prior screening and may still need ongoing testing.12

Continue to: Primary HPV screening...

Primary HPV screening

Primary HPV testing means that an HPV test is performed first, and if it is positive for high-risk HPV, further testing is performed to determine next steps. This contrasts with the currently used method of obtaining cytology (Pap) first with either concurrent HPV testing or reflex HPV testing. The first HPV primary screening test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014.13

Multiple randomized controlled trials in Europe have demonstrated the accuracy of HPV-based screening compared with cytology in the detection of cervical cancer and its precursors.14-17 The HPV FOCAL trial demonstrated increased efficacy of primary HPV screening in the detection of CIN 2+ lesions.18 This trial recruited a total of 19,000 women, ages 25 to 65, in Canada and randomly assigned them to receive primary HPV testing or liquid-based cytology. If primary HPV testing was negative, participants would return in 48 months for cytology and HPV cotesting. If primary liquid-based cytology testing was negative, participants would return at 24 months for cytology testing alone and at 48 months for cytology and HPV cotesting. Both groups had similar incidences of CIN 2+ over the study period. HPV testing was shown to detect CIN 2+ at higher rates at the time of initial screen (risk ratio [RR], 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–2.09) and then significantly lower rates at the time of exit screening at 48 months (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24–0.54).18 These results demonstrated that primary HPV testing detects CIN 2+ earlier than cytology alone. In follow-up analyses, primary HPV screening missed fewer CIN 2+ diagnoses than cytology screening.19

While not as many studies have compared primary HPV testing to cytology with an HPV cotest, the current most common practice in the United States, one study performed in the United States found that a negative cytology result did not further decrease the risk of CIN 3 for HPV-negative patients (risk of CIN 3+ at 5 years: 0.16% vs 0.17%; P=0.8) and concluded that a negative HPV test was enough reassurance for a low risk of CIN 3+.20

Another study, the ATHENA trial, evaluated more than 42,000 women who were 25 years and older over a 3-year period.21 Patients underwent either primary HPV testing or combination cytology and reflex HPV (if ages 25–29) or HPV cotesting (if age 30 or older). Primary HPV testing was found to have a sensitivity and specificity of 76.1% and 93.5%, respectively, compared with 61.7% and 94.6% for cytology with HPV cotesting, but it also increased the total number of colposcopies performed.21

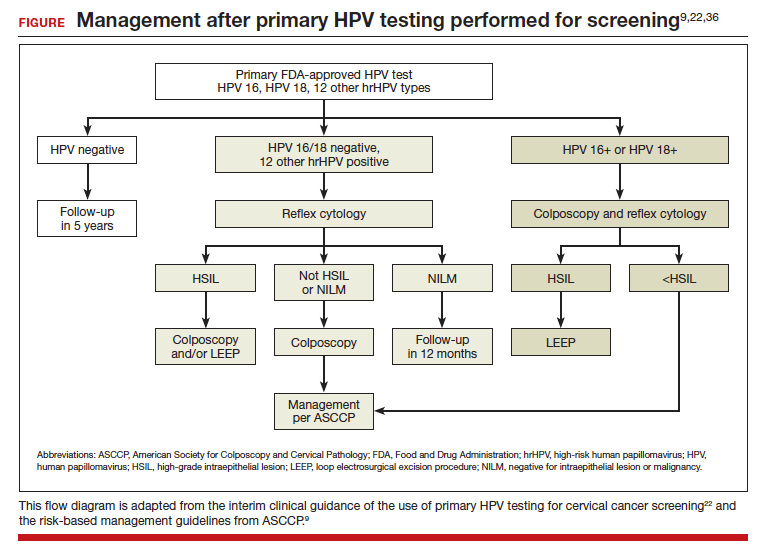

Subsequent management of a primary HPV-positive result can be triaged using genotyping, cytology, or a combination of both. FDA-approved HPV screening tests provide genotyping and current management guidelines use genotyping to triage positive HPV results into HPV 16, 18, or 1 of 12 other high-risk HPV genotypes.

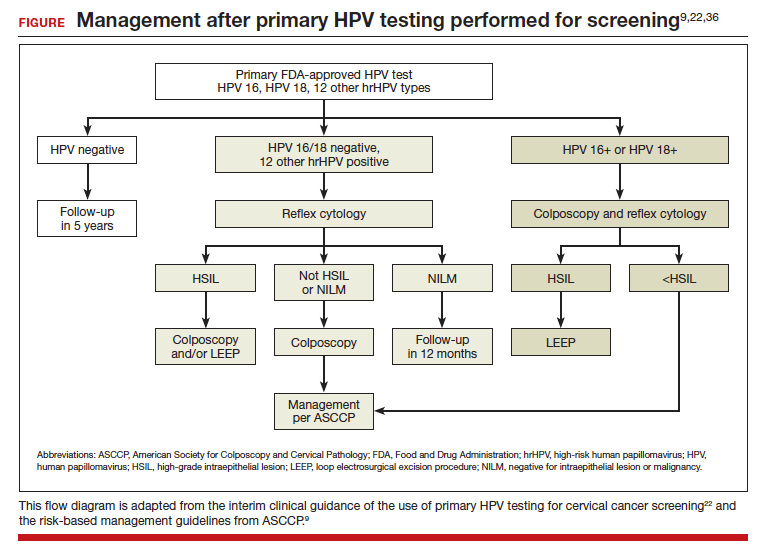

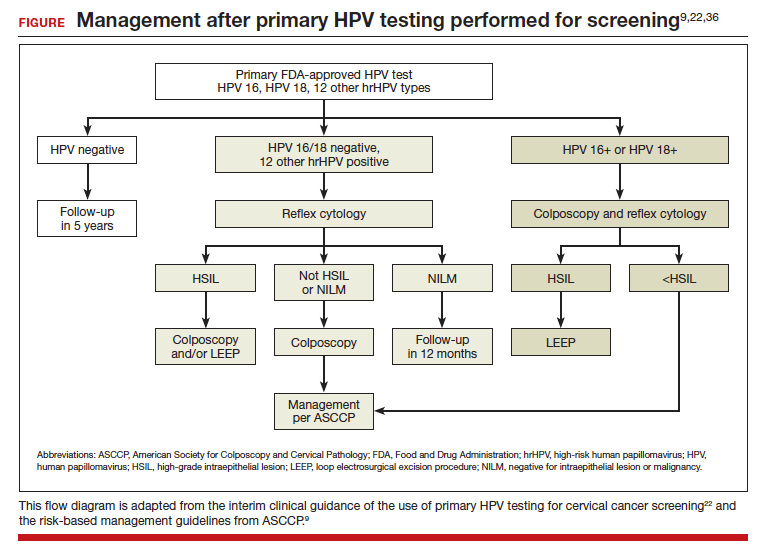

In the ATHENA trial, the 3-year incidence of CIN 3+ for HPV 16/18-positive results was 21.16% (95% CI, 18.39%–24.01%) compared with 5.4% (95% CI, 4.5%–6.4%) among patients with an HPV test positive for 1 of the other HPV genotypes.21 While a patient with an HPV result positive for HPV 16/18 should directly undergo colposcopy, clinical guidance for an HPV-positive result for one of the other genotypes suggests using reflex cytology to triage patients. The ASCCP recommended management of primary HPV testing is included in the FIGURE.22

Many barriers remain to transitioning to primary HPV testing, including laboratory test availability as well as patient and provider acceptance. At present, 2 FDA-approved primary HPV screening tests are available: the Cobas HPV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Changes to screening recommendations need to be accompanied by patient and provider outreach and education.

In a survey of more than 500 US women in 2015 after guidelines allowed for increased screening intervals after negative results, a majority of women (55.6%; 95% CI, 51.4%–59.8%) were aware that screening recommendations had changed; however, 74.1% (95% CI, 70.3%–77.7%) still believed that women should be screened annually.23 By contrast, participants in the HPV FOCAL trial, who were able to learn more about HPV-based screening, were surveyed about their willingness to undergo primary HPV testing rather than Pap testing at the conclusion of the trial.24 Of the participants, 63% were comfortable with primary HPV testing, and 54% were accepting of an extended screening interval of 4 to 5 years.24

Continue to: p16/Ki-67 dual-stain cytology...

p16/Ki-67 dual-stain cytology

An additional tool for triaging HPV-positive patients is the p16/Ki-67 dual stain test (CINtec Plus Cytology; Roche), which was FDA approved in March 2020. A tumor suppressor protein, p16 is found to be overexpressed by HPV oncogenic activity, and Ki-67 is a marker of cellular proliferation. Coexpression of p16 and Ki-67 indicates a loss of cell cycle regulation and is a hallmark of neoplastic transformation. When positive, this test is supportive of active HPV infection and of a high-grade lesion. While the dual stain test is not yet formally incorporated into triage algorithms by national guidelines, it has demonstrated efficacy in detecting CIN 3+

In the IMPACT trial, nearly 5,000 HPV-positive patients underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain testing compared with cytology and HPV genotyping.25 The sensitivity of dual stain for CIN 3+ was 91.9% (95% CI, 86.1%–95.4%) in HPV 16/18–positive and 86.0% (95% CI, 77.5%–91.6%) in the 12 other genotypes. Using dual stain testing alone to triage HPV-positive results showed significantly higher sensitivity but lower specificity than using cytology alone to triage HPV-positive results. Importantly, triage with dual stain testing alone would have referred significantly fewer women to colposcopy than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage for the 12 other genotypes (48.6% vs 56.0%; P< .0001).

Self-sampling methods: An approach for potentially improving access to screening

One technology that may help bridge gaps in access to cervical cancer screening is self-collected HPV testing, which would preclude the need for a clinician-performed pelvic exam. At present, no self-sampling method is approved by the FDA. However, many studies have examined the efficacy and safety of various self-sampling kits.26

One randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared sensitivity and specificity of CIN 2+ detection in patient-collected versus clinician-collected swabs.27 After a median follow-up of 20 months, the sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing did not differ between the patient-collected and the clinician-collected groups (specificity 100%; 95% CI, 0.91–1.08; sensitivity 96%; 95% CI, 0.90–1.03).27 This analysis did not include patients who did not return their self-collected sample, which leaves the question of whether self-sampling may exacerbate issues with patients who are lost to follow-up.

In a study performed in the United States, 16,590 patients who were overdue for cervical cancer screening were randomly assigned to usual care reminders (annual mailed reminders and phone calls from clinics) or to the addition of a mailed HPV self-sampling test kit.28 While the study did not demonstrate significant difference in the detection of overall CIN 2+ between the 2 groups, screening uptake was higher in the self-sampling kit group than in the usual care reminders group (RR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.43–1.60), and the number of abnormal screens that warranted colposcopy referral was similar between the 2 groups (36.4% vs 36.8%).28 In qualitative interviews of the participants of this trial, patients who were sent at-home self-sampling kits found that the convenience of at-home testing lowered barriers to scheduling an in-office appointment.29 The hope is that self-sampling methods will expand access of cervical cancer screening to vulnerable populations that face significant barriers to having an in-office pelvic exam.

It is important to note that self-collection and self-sample testing requires multidisciplinary systems for processing results and assuring necessary patient follow-up. Implementing and disseminating such a program has been well tested only in developed countries27,30 with universal health care systems or within an integrated care delivery system. Bringing such technology broadly to the United States and less developed countries will require continued commitment to increasing laboratory capacity, a central electronic health record or system for monitoring results, educational materials for clinicians and patients, and expanding insurance reimbursement for such testing.

HPV vaccination rates must increase

While we continue to investigate which screening methods will most improve our secondary prevention of cervical cancer, our path to increasing primary prevention of cervical cancer is clear: We must increase rates of HPV vaccination. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is FDA approved for use in all patients aged 9 to 45 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other organizations recommend HPV vaccination between the ages of 9 and 13, and a “catch-up period” from ages 13 to 26 in which patients previously not vaccinated should receive the vaccine.31 Initiation of the vaccine course earlier (ages 9–10) compared with later (ages 11–12) is correlated with higher overall completion rates by age 15 and has been suggested to be associated with a stronger immune response.32

A study from Sweden found that HPV vaccination before age 17 was most strongly correlated with the lowest rates of cervical cancer, although vaccination between ages 17 and 30 still significantly decreased the risk of cervical cancer compared with those who were unvaccinated.33

Overall HPV vaccination rates in the United States continue to improve, with 58.6%34 of US adolescents having completed vaccination in 2020. However, these rates still are significantly lower than those in many other developed countries, including Australia, which had a complete vaccination rate of 80.5% in 2020.35 Continued disparities in vaccination rates could be contributing to the rise in cervical cancer among certain groups, such as American Indian and Alaska Native populations.5

Work—and innovations—must continue

In conclusion, the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States continues to decrease, although at disparate rates among marginalized populations. To ensure that we are working toward eliminating cervical cancer for all patients, we must continue efforts to eliminate disparities in health access. Continued innovations, including primary HPV testing and self-collection samples, may contribute to lowering barriers to all patients being able to access the preventative care they need. ●

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States Cancer Statistics: data visualizations. Trends: changes over time: cervix. Accessed January 8, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov /Cancer/USCS/#/Trends/

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660.

- Francoeur AA, Liao CI, Casear MA, et al. The increasing incidence of stage IV cervical cancer in the USA: what factors are related? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:ijgc-2022-003728. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003728.

- Abdalla E, Habtemariam T, Fall S, et al. A comparative study of health disparities in cervical cancer mortality rates through time between Black and Caucasian women in Alabama and the US. Int J Stud Nurs. 2021;6:9-23. doi:10.20849/ijsn. v6i1.864.

- Bruegl AS, Emerson J, Tirumala K. Persistent disparities of cervical cancer among American Indians/Alaska natives: are we maximizing prevention tools? Gynecol Oncol. 2023;168:5661. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.11.007.

- Suk R, Hong YR, Rajan SS, et al. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force Guideline–Concordant cervical cancer screening rates and reasons for underscreening by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, rurality, and insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2143582. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2021.43582.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897.

- Nayar R, Chhieng DC, Crothers B, et al. Moving forward—the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors and beyond: implications and suggestions for laboratories. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020;9:291-303. doi:10.1016/j.jasc.2020.05.002.

- Cooley JJP, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov /statfacts/html/cervix.html

- Feldman S. Screening options for preventing cervical cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:879-880. doi:10.1001/ jamainternmed.2019.0298.

- ASCO Post Staff. FDA approves first HPV test for primary cervical cancer screening. ASCO Post. May 15, 2014. Accessed January 8, 2023. https://ascopost.com/issues/may-15-2014 /fda-approves-first-hpv-test-for-primary-cervical-cancer -screening/

- Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70296-0.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2.

- Kitchener HC, Almonte M, Thomson C, et al. HPV testing in combination with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical screening (ARTISTIC): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:672-682. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70156-1.

- Bulkmans NWJ, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year followup of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61450-0.

- Ogilvie GS, Van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7464.

- Gottschlich A, Gondara L, Smith LW, et al. Human papillomavirus‐based screening at extended intervals missed fewer cervical precancers than cytology in the HPV For Cervical Cancer (HPV FOCAL) trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:897-905. doi:10.1002/ijc.34039.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663672. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.076

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330-337. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669.

- Silver MI, Rositch AF, Burke AE, et al. Patient concerns about human papillomavirus testing and 5-year intervals in routine cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:317-329. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000638.

- Smith LW, Racey CS, Gondara L, et al. Women’s acceptability of and experience with primary human papillomavirus testing for cervical screening: HPV FOCAL trial cross-sectional online survey results. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e052084. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052084.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Clinical validation of p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology triage of HPV-positive women: results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:461-471. doi:10.1002/ijc.33812.

- Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, De Vuyst H, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4:e001351. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001351.

- Polman NJ, Ebisch RMF, Heideman DAM, et al. Performance of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of grade 2 or worse: a randomised, paired screen-positive, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:229-238. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30763-0.

- Winer RL, Lin J, Tiro JA, et al. Effect of mailed human papillomavirus test kits vs usual care reminders on cervical cancer screening uptake, precancer detection, and treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914729. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14729.

- Tiro JA, Betts AC, Kimbel K, et al. Understanding patients’ perspectives and information needs following a positive home human papillomavirus self-sampling kit result. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28:384-392. doi:10.1089/ jwh.2018.7070.

- Knauss T, Hansen BT, Pedersen K, et al. The cost-effectiveness of opt-in and send-to-all HPV self-sampling among long-term non-attenders to cervical cancer screening in Norway: the Equalscreen randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;168:39-47. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.10.027.

- ACOG committee opinion no. 809. Human papillomavirus vaccination: correction. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:345. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004680.

- St Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, et al. Younger age at initiation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016;89:327-333. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:13401348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1183-1190. doi:10.15585/ mmwr.mm7035a1.

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Australia. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2020. November 29, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://ncirs .org.au/sites/default/files/2021-11/NCIRS%20Annual%20 Immunisation%20Coverage%20Report%202020_FINAL.pdf

- Leung SOA, Feldman S. 2022 Update on cervical disease. OBG Manag. 2022;34(5):16-17, 22-24, 26, 28. doi:10.12788/ obgm.0197.

CASE Intervention approaches for decreasing the risk of cervical cancer

A 25-year-old woman presents to your practice for routine examination. She has never undergone cervical cancer screening or received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series. The patient has had 3 lifetime sexual partners and currently uses condoms as contraception. What interventions are appropriate to offer this patient to decrease her risk of cervical cancer? Choose as many that may apply:

1. cervical cytology with reflex HPV testing

2. cervical cytology with HPV cotesting

3. primary HPV testing

4. HPV vaccine series (3 doses)

5. all of the above

The answer is number 5, all of the above.

Choices 1, 2, and 3 are acceptable methods of cervical cancer screening for this patient. Catch-up HPV vaccination should be offered as well.

Equitable preventive care is needed

Cervical cancer is a unique cancer because it has a known preventative strategy. HPV vaccination, paired with cervical screening and management of abnormal results, has contributed to decreased rates of cervical cancer in the United States, from 13,914 cases in 1999 to 12,795 cases in 2019.1 In less-developed countries, however, cervical cancer continues to be a leading cause of mortality, with 90% of cervical cancer deaths in 2020 occurring in low- and middle-income countries.2

Disparate outcomes in cervical cancer are often a reflection of disparities in health access. Within the United States, Black women have a higher incidence of cervical cancer, advanced-stage disease, and mortality from cervical cancer than White women.3,4 Furthermore, the incidence of cervical cancer increased among American Indian and Alaska Native people between 2000 and 2019.5 The rate for patients who are overdue for cervical cancer screening is higher among Asian and Hispanic patients compared with non-Hispanic White patients (31.4% vs 20.1%; P=.01) and among patients who identify as LGBTQ+ compared with patients who identify as heterosexual (32.0% vs 22.2%; P<.001).6 Younger patients have a significantly higher rate for overdue screening compared with their older counterparts (29.1% vs 21.1%; P<.001), as do uninsured patients compared with those who are privately insured (41.7% vs 18.1%; P<.001). Overall, the proportion of women without up-to-date screening increased significantly from 2005 to 2019 (14.4% vs 23.0%; P<.001).6

Unfortunately, despite a known strategy to eliminate cervical cancer, we are not accomplishing equitable preventative care. Barriers to care can include patient-centered issues, such as fear of cancer or of painful evaluations, lack of trust in the health care system, and inadequate understanding of the benefits of cancer prevention, in addition to systemic and structural barriers. As we assess new technologies, one of our most important goals is to consider how such innovations can increase health access—whether through increasing ease and acceptability of testing or by creating more effective screening tests.

Updates to cervical screening guidance

In 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) updated its cervical screening guidelines to start screening at age 25 years with the “preferred” strategy of HPV primary testing every 5 years.7 By contrast, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) continues to recommend 1 of 3 methods: cytology alone every 3 years; cytology alone every 3 years between ages 21 and 29 followed by cytology and HPV cotesting every 5 years at age 30 or older; or high-risk HPV testing alone every 5 years (TABLE).8

To successfully prevent cervical cancer, abnormal results are managed by performing either colposcopy with biopsy, immediate treatment, or close surveillance based on the risk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3 or worse. A patient’s risk is determined based on both current and prior test results. The ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) transitioned to risk-based management guidelines in 2019 and has both an app and a web-based risk assessment tool available for clinicians (https://www.asccp.org).9

All organizations recommend stopping screening after age 65 provided there has been a history of adequate screening in the prior 10 years (defined as 2 normal cotests or 3 normal cytology tests, with the most recent test within 5 years) and no history of CIN 2 or worse within the prior 25 years.10,11 Recent studies that examined the rate of cervical cancer diagnosed in patients older than 65 years have questioned whether patients should continue screening beyond 65.10 In the United States, 20% of cervical cancer still occurs in women older than age 65.11 One reason may be that many women have not met the requirement for adequate and normal prior screening and may still need ongoing testing.12

Continue to: Primary HPV screening...

Primary HPV screening

Primary HPV testing means that an HPV test is performed first, and if it is positive for high-risk HPV, further testing is performed to determine next steps. This contrasts with the currently used method of obtaining cytology (Pap) first with either concurrent HPV testing or reflex HPV testing. The first HPV primary screening test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014.13

Multiple randomized controlled trials in Europe have demonstrated the accuracy of HPV-based screening compared with cytology in the detection of cervical cancer and its precursors.14-17 The HPV FOCAL trial demonstrated increased efficacy of primary HPV screening in the detection of CIN 2+ lesions.18 This trial recruited a total of 19,000 women, ages 25 to 65, in Canada and randomly assigned them to receive primary HPV testing or liquid-based cytology. If primary HPV testing was negative, participants would return in 48 months for cytology and HPV cotesting. If primary liquid-based cytology testing was negative, participants would return at 24 months for cytology testing alone and at 48 months for cytology and HPV cotesting. Both groups had similar incidences of CIN 2+ over the study period. HPV testing was shown to detect CIN 2+ at higher rates at the time of initial screen (risk ratio [RR], 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–2.09) and then significantly lower rates at the time of exit screening at 48 months (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24–0.54).18 These results demonstrated that primary HPV testing detects CIN 2+ earlier than cytology alone. In follow-up analyses, primary HPV screening missed fewer CIN 2+ diagnoses than cytology screening.19

While not as many studies have compared primary HPV testing to cytology with an HPV cotest, the current most common practice in the United States, one study performed in the United States found that a negative cytology result did not further decrease the risk of CIN 3 for HPV-negative patients (risk of CIN 3+ at 5 years: 0.16% vs 0.17%; P=0.8) and concluded that a negative HPV test was enough reassurance for a low risk of CIN 3+.20

Another study, the ATHENA trial, evaluated more than 42,000 women who were 25 years and older over a 3-year period.21 Patients underwent either primary HPV testing or combination cytology and reflex HPV (if ages 25–29) or HPV cotesting (if age 30 or older). Primary HPV testing was found to have a sensitivity and specificity of 76.1% and 93.5%, respectively, compared with 61.7% and 94.6% for cytology with HPV cotesting, but it also increased the total number of colposcopies performed.21

Subsequent management of a primary HPV-positive result can be triaged using genotyping, cytology, or a combination of both. FDA-approved HPV screening tests provide genotyping and current management guidelines use genotyping to triage positive HPV results into HPV 16, 18, or 1 of 12 other high-risk HPV genotypes.

In the ATHENA trial, the 3-year incidence of CIN 3+ for HPV 16/18-positive results was 21.16% (95% CI, 18.39%–24.01%) compared with 5.4% (95% CI, 4.5%–6.4%) among patients with an HPV test positive for 1 of the other HPV genotypes.21 While a patient with an HPV result positive for HPV 16/18 should directly undergo colposcopy, clinical guidance for an HPV-positive result for one of the other genotypes suggests using reflex cytology to triage patients. The ASCCP recommended management of primary HPV testing is included in the FIGURE.22

Many barriers remain to transitioning to primary HPV testing, including laboratory test availability as well as patient and provider acceptance. At present, 2 FDA-approved primary HPV screening tests are available: the Cobas HPV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Changes to screening recommendations need to be accompanied by patient and provider outreach and education.

In a survey of more than 500 US women in 2015 after guidelines allowed for increased screening intervals after negative results, a majority of women (55.6%; 95% CI, 51.4%–59.8%) were aware that screening recommendations had changed; however, 74.1% (95% CI, 70.3%–77.7%) still believed that women should be screened annually.23 By contrast, participants in the HPV FOCAL trial, who were able to learn more about HPV-based screening, were surveyed about their willingness to undergo primary HPV testing rather than Pap testing at the conclusion of the trial.24 Of the participants, 63% were comfortable with primary HPV testing, and 54% were accepting of an extended screening interval of 4 to 5 years.24

Continue to: p16/Ki-67 dual-stain cytology...

p16/Ki-67 dual-stain cytology

An additional tool for triaging HPV-positive patients is the p16/Ki-67 dual stain test (CINtec Plus Cytology; Roche), which was FDA approved in March 2020. A tumor suppressor protein, p16 is found to be overexpressed by HPV oncogenic activity, and Ki-67 is a marker of cellular proliferation. Coexpression of p16 and Ki-67 indicates a loss of cell cycle regulation and is a hallmark of neoplastic transformation. When positive, this test is supportive of active HPV infection and of a high-grade lesion. While the dual stain test is not yet formally incorporated into triage algorithms by national guidelines, it has demonstrated efficacy in detecting CIN 3+

In the IMPACT trial, nearly 5,000 HPV-positive patients underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain testing compared with cytology and HPV genotyping.25 The sensitivity of dual stain for CIN 3+ was 91.9% (95% CI, 86.1%–95.4%) in HPV 16/18–positive and 86.0% (95% CI, 77.5%–91.6%) in the 12 other genotypes. Using dual stain testing alone to triage HPV-positive results showed significantly higher sensitivity but lower specificity than using cytology alone to triage HPV-positive results. Importantly, triage with dual stain testing alone would have referred significantly fewer women to colposcopy than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage for the 12 other genotypes (48.6% vs 56.0%; P< .0001).

Self-sampling methods: An approach for potentially improving access to screening

One technology that may help bridge gaps in access to cervical cancer screening is self-collected HPV testing, which would preclude the need for a clinician-performed pelvic exam. At present, no self-sampling method is approved by the FDA. However, many studies have examined the efficacy and safety of various self-sampling kits.26

One randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared sensitivity and specificity of CIN 2+ detection in patient-collected versus clinician-collected swabs.27 After a median follow-up of 20 months, the sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing did not differ between the patient-collected and the clinician-collected groups (specificity 100%; 95% CI, 0.91–1.08; sensitivity 96%; 95% CI, 0.90–1.03).27 This analysis did not include patients who did not return their self-collected sample, which leaves the question of whether self-sampling may exacerbate issues with patients who are lost to follow-up.

In a study performed in the United States, 16,590 patients who were overdue for cervical cancer screening were randomly assigned to usual care reminders (annual mailed reminders and phone calls from clinics) or to the addition of a mailed HPV self-sampling test kit.28 While the study did not demonstrate significant difference in the detection of overall CIN 2+ between the 2 groups, screening uptake was higher in the self-sampling kit group than in the usual care reminders group (RR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.43–1.60), and the number of abnormal screens that warranted colposcopy referral was similar between the 2 groups (36.4% vs 36.8%).28 In qualitative interviews of the participants of this trial, patients who were sent at-home self-sampling kits found that the convenience of at-home testing lowered barriers to scheduling an in-office appointment.29 The hope is that self-sampling methods will expand access of cervical cancer screening to vulnerable populations that face significant barriers to having an in-office pelvic exam.

It is important to note that self-collection and self-sample testing requires multidisciplinary systems for processing results and assuring necessary patient follow-up. Implementing and disseminating such a program has been well tested only in developed countries27,30 with universal health care systems or within an integrated care delivery system. Bringing such technology broadly to the United States and less developed countries will require continued commitment to increasing laboratory capacity, a central electronic health record or system for monitoring results, educational materials for clinicians and patients, and expanding insurance reimbursement for such testing.

HPV vaccination rates must increase

While we continue to investigate which screening methods will most improve our secondary prevention of cervical cancer, our path to increasing primary prevention of cervical cancer is clear: We must increase rates of HPV vaccination. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is FDA approved for use in all patients aged 9 to 45 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other organizations recommend HPV vaccination between the ages of 9 and 13, and a “catch-up period” from ages 13 to 26 in which patients previously not vaccinated should receive the vaccine.31 Initiation of the vaccine course earlier (ages 9–10) compared with later (ages 11–12) is correlated with higher overall completion rates by age 15 and has been suggested to be associated with a stronger immune response.32

A study from Sweden found that HPV vaccination before age 17 was most strongly correlated with the lowest rates of cervical cancer, although vaccination between ages 17 and 30 still significantly decreased the risk of cervical cancer compared with those who were unvaccinated.33

Overall HPV vaccination rates in the United States continue to improve, with 58.6%34 of US adolescents having completed vaccination in 2020. However, these rates still are significantly lower than those in many other developed countries, including Australia, which had a complete vaccination rate of 80.5% in 2020.35 Continued disparities in vaccination rates could be contributing to the rise in cervical cancer among certain groups, such as American Indian and Alaska Native populations.5

Work—and innovations—must continue

In conclusion, the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States continues to decrease, although at disparate rates among marginalized populations. To ensure that we are working toward eliminating cervical cancer for all patients, we must continue efforts to eliminate disparities in health access. Continued innovations, including primary HPV testing and self-collection samples, may contribute to lowering barriers to all patients being able to access the preventative care they need. ●

CASE Intervention approaches for decreasing the risk of cervical cancer

A 25-year-old woman presents to your practice for routine examination. She has never undergone cervical cancer screening or received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series. The patient has had 3 lifetime sexual partners and currently uses condoms as contraception. What interventions are appropriate to offer this patient to decrease her risk of cervical cancer? Choose as many that may apply:

1. cervical cytology with reflex HPV testing

2. cervical cytology with HPV cotesting

3. primary HPV testing

4. HPV vaccine series (3 doses)

5. all of the above

The answer is number 5, all of the above.

Choices 1, 2, and 3 are acceptable methods of cervical cancer screening for this patient. Catch-up HPV vaccination should be offered as well.

Equitable preventive care is needed

Cervical cancer is a unique cancer because it has a known preventative strategy. HPV vaccination, paired with cervical screening and management of abnormal results, has contributed to decreased rates of cervical cancer in the United States, from 13,914 cases in 1999 to 12,795 cases in 2019.1 In less-developed countries, however, cervical cancer continues to be a leading cause of mortality, with 90% of cervical cancer deaths in 2020 occurring in low- and middle-income countries.2

Disparate outcomes in cervical cancer are often a reflection of disparities in health access. Within the United States, Black women have a higher incidence of cervical cancer, advanced-stage disease, and mortality from cervical cancer than White women.3,4 Furthermore, the incidence of cervical cancer increased among American Indian and Alaska Native people between 2000 and 2019.5 The rate for patients who are overdue for cervical cancer screening is higher among Asian and Hispanic patients compared with non-Hispanic White patients (31.4% vs 20.1%; P=.01) and among patients who identify as LGBTQ+ compared with patients who identify as heterosexual (32.0% vs 22.2%; P<.001).6 Younger patients have a significantly higher rate for overdue screening compared with their older counterparts (29.1% vs 21.1%; P<.001), as do uninsured patients compared with those who are privately insured (41.7% vs 18.1%; P<.001). Overall, the proportion of women without up-to-date screening increased significantly from 2005 to 2019 (14.4% vs 23.0%; P<.001).6

Unfortunately, despite a known strategy to eliminate cervical cancer, we are not accomplishing equitable preventative care. Barriers to care can include patient-centered issues, such as fear of cancer or of painful evaluations, lack of trust in the health care system, and inadequate understanding of the benefits of cancer prevention, in addition to systemic and structural barriers. As we assess new technologies, one of our most important goals is to consider how such innovations can increase health access—whether through increasing ease and acceptability of testing or by creating more effective screening tests.

Updates to cervical screening guidance

In 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) updated its cervical screening guidelines to start screening at age 25 years with the “preferred” strategy of HPV primary testing every 5 years.7 By contrast, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) continues to recommend 1 of 3 methods: cytology alone every 3 years; cytology alone every 3 years between ages 21 and 29 followed by cytology and HPV cotesting every 5 years at age 30 or older; or high-risk HPV testing alone every 5 years (TABLE).8

To successfully prevent cervical cancer, abnormal results are managed by performing either colposcopy with biopsy, immediate treatment, or close surveillance based on the risk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3 or worse. A patient’s risk is determined based on both current and prior test results. The ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) transitioned to risk-based management guidelines in 2019 and has both an app and a web-based risk assessment tool available for clinicians (https://www.asccp.org).9

All organizations recommend stopping screening after age 65 provided there has been a history of adequate screening in the prior 10 years (defined as 2 normal cotests or 3 normal cytology tests, with the most recent test within 5 years) and no history of CIN 2 or worse within the prior 25 years.10,11 Recent studies that examined the rate of cervical cancer diagnosed in patients older than 65 years have questioned whether patients should continue screening beyond 65.10 In the United States, 20% of cervical cancer still occurs in women older than age 65.11 One reason may be that many women have not met the requirement for adequate and normal prior screening and may still need ongoing testing.12

Continue to: Primary HPV screening...

Primary HPV screening

Primary HPV testing means that an HPV test is performed first, and if it is positive for high-risk HPV, further testing is performed to determine next steps. This contrasts with the currently used method of obtaining cytology (Pap) first with either concurrent HPV testing or reflex HPV testing. The first HPV primary screening test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014.13

Multiple randomized controlled trials in Europe have demonstrated the accuracy of HPV-based screening compared with cytology in the detection of cervical cancer and its precursors.14-17 The HPV FOCAL trial demonstrated increased efficacy of primary HPV screening in the detection of CIN 2+ lesions.18 This trial recruited a total of 19,000 women, ages 25 to 65, in Canada and randomly assigned them to receive primary HPV testing or liquid-based cytology. If primary HPV testing was negative, participants would return in 48 months for cytology and HPV cotesting. If primary liquid-based cytology testing was negative, participants would return at 24 months for cytology testing alone and at 48 months for cytology and HPV cotesting. Both groups had similar incidences of CIN 2+ over the study period. HPV testing was shown to detect CIN 2+ at higher rates at the time of initial screen (risk ratio [RR], 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–2.09) and then significantly lower rates at the time of exit screening at 48 months (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24–0.54).18 These results demonstrated that primary HPV testing detects CIN 2+ earlier than cytology alone. In follow-up analyses, primary HPV screening missed fewer CIN 2+ diagnoses than cytology screening.19

While not as many studies have compared primary HPV testing to cytology with an HPV cotest, the current most common practice in the United States, one study performed in the United States found that a negative cytology result did not further decrease the risk of CIN 3 for HPV-negative patients (risk of CIN 3+ at 5 years: 0.16% vs 0.17%; P=0.8) and concluded that a negative HPV test was enough reassurance for a low risk of CIN 3+.20

Another study, the ATHENA trial, evaluated more than 42,000 women who were 25 years and older over a 3-year period.21 Patients underwent either primary HPV testing or combination cytology and reflex HPV (if ages 25–29) or HPV cotesting (if age 30 or older). Primary HPV testing was found to have a sensitivity and specificity of 76.1% and 93.5%, respectively, compared with 61.7% and 94.6% for cytology with HPV cotesting, but it also increased the total number of colposcopies performed.21

Subsequent management of a primary HPV-positive result can be triaged using genotyping, cytology, or a combination of both. FDA-approved HPV screening tests provide genotyping and current management guidelines use genotyping to triage positive HPV results into HPV 16, 18, or 1 of 12 other high-risk HPV genotypes.

In the ATHENA trial, the 3-year incidence of CIN 3+ for HPV 16/18-positive results was 21.16% (95% CI, 18.39%–24.01%) compared with 5.4% (95% CI, 4.5%–6.4%) among patients with an HPV test positive for 1 of the other HPV genotypes.21 While a patient with an HPV result positive for HPV 16/18 should directly undergo colposcopy, clinical guidance for an HPV-positive result for one of the other genotypes suggests using reflex cytology to triage patients. The ASCCP recommended management of primary HPV testing is included in the FIGURE.22

Many barriers remain to transitioning to primary HPV testing, including laboratory test availability as well as patient and provider acceptance. At present, 2 FDA-approved primary HPV screening tests are available: the Cobas HPV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Changes to screening recommendations need to be accompanied by patient and provider outreach and education.

In a survey of more than 500 US women in 2015 after guidelines allowed for increased screening intervals after negative results, a majority of women (55.6%; 95% CI, 51.4%–59.8%) were aware that screening recommendations had changed; however, 74.1% (95% CI, 70.3%–77.7%) still believed that women should be screened annually.23 By contrast, participants in the HPV FOCAL trial, who were able to learn more about HPV-based screening, were surveyed about their willingness to undergo primary HPV testing rather than Pap testing at the conclusion of the trial.24 Of the participants, 63% were comfortable with primary HPV testing, and 54% were accepting of an extended screening interval of 4 to 5 years.24

Continue to: p16/Ki-67 dual-stain cytology...

p16/Ki-67 dual-stain cytology

An additional tool for triaging HPV-positive patients is the p16/Ki-67 dual stain test (CINtec Plus Cytology; Roche), which was FDA approved in March 2020. A tumor suppressor protein, p16 is found to be overexpressed by HPV oncogenic activity, and Ki-67 is a marker of cellular proliferation. Coexpression of p16 and Ki-67 indicates a loss of cell cycle regulation and is a hallmark of neoplastic transformation. When positive, this test is supportive of active HPV infection and of a high-grade lesion. While the dual stain test is not yet formally incorporated into triage algorithms by national guidelines, it has demonstrated efficacy in detecting CIN 3+

In the IMPACT trial, nearly 5,000 HPV-positive patients underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain testing compared with cytology and HPV genotyping.25 The sensitivity of dual stain for CIN 3+ was 91.9% (95% CI, 86.1%–95.4%) in HPV 16/18–positive and 86.0% (95% CI, 77.5%–91.6%) in the 12 other genotypes. Using dual stain testing alone to triage HPV-positive results showed significantly higher sensitivity but lower specificity than using cytology alone to triage HPV-positive results. Importantly, triage with dual stain testing alone would have referred significantly fewer women to colposcopy than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage for the 12 other genotypes (48.6% vs 56.0%; P< .0001).

Self-sampling methods: An approach for potentially improving access to screening

One technology that may help bridge gaps in access to cervical cancer screening is self-collected HPV testing, which would preclude the need for a clinician-performed pelvic exam. At present, no self-sampling method is approved by the FDA. However, many studies have examined the efficacy and safety of various self-sampling kits.26

One randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared sensitivity and specificity of CIN 2+ detection in patient-collected versus clinician-collected swabs.27 After a median follow-up of 20 months, the sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing did not differ between the patient-collected and the clinician-collected groups (specificity 100%; 95% CI, 0.91–1.08; sensitivity 96%; 95% CI, 0.90–1.03).27 This analysis did not include patients who did not return their self-collected sample, which leaves the question of whether self-sampling may exacerbate issues with patients who are lost to follow-up.

In a study performed in the United States, 16,590 patients who were overdue for cervical cancer screening were randomly assigned to usual care reminders (annual mailed reminders and phone calls from clinics) or to the addition of a mailed HPV self-sampling test kit.28 While the study did not demonstrate significant difference in the detection of overall CIN 2+ between the 2 groups, screening uptake was higher in the self-sampling kit group than in the usual care reminders group (RR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.43–1.60), and the number of abnormal screens that warranted colposcopy referral was similar between the 2 groups (36.4% vs 36.8%).28 In qualitative interviews of the participants of this trial, patients who were sent at-home self-sampling kits found that the convenience of at-home testing lowered barriers to scheduling an in-office appointment.29 The hope is that self-sampling methods will expand access of cervical cancer screening to vulnerable populations that face significant barriers to having an in-office pelvic exam.

It is important to note that self-collection and self-sample testing requires multidisciplinary systems for processing results and assuring necessary patient follow-up. Implementing and disseminating such a program has been well tested only in developed countries27,30 with universal health care systems or within an integrated care delivery system. Bringing such technology broadly to the United States and less developed countries will require continued commitment to increasing laboratory capacity, a central electronic health record or system for monitoring results, educational materials for clinicians and patients, and expanding insurance reimbursement for such testing.

HPV vaccination rates must increase

While we continue to investigate which screening methods will most improve our secondary prevention of cervical cancer, our path to increasing primary prevention of cervical cancer is clear: We must increase rates of HPV vaccination. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is FDA approved for use in all patients aged 9 to 45 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other organizations recommend HPV vaccination between the ages of 9 and 13, and a “catch-up period” from ages 13 to 26 in which patients previously not vaccinated should receive the vaccine.31 Initiation of the vaccine course earlier (ages 9–10) compared with later (ages 11–12) is correlated with higher overall completion rates by age 15 and has been suggested to be associated with a stronger immune response.32

A study from Sweden found that HPV vaccination before age 17 was most strongly correlated with the lowest rates of cervical cancer, although vaccination between ages 17 and 30 still significantly decreased the risk of cervical cancer compared with those who were unvaccinated.33

Overall HPV vaccination rates in the United States continue to improve, with 58.6%34 of US adolescents having completed vaccination in 2020. However, these rates still are significantly lower than those in many other developed countries, including Australia, which had a complete vaccination rate of 80.5% in 2020.35 Continued disparities in vaccination rates could be contributing to the rise in cervical cancer among certain groups, such as American Indian and Alaska Native populations.5

Work—and innovations—must continue

In conclusion, the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States continues to decrease, although at disparate rates among marginalized populations. To ensure that we are working toward eliminating cervical cancer for all patients, we must continue efforts to eliminate disparities in health access. Continued innovations, including primary HPV testing and self-collection samples, may contribute to lowering barriers to all patients being able to access the preventative care they need. ●

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States Cancer Statistics: data visualizations. Trends: changes over time: cervix. Accessed January 8, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov /Cancer/USCS/#/Trends/

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660.

- Francoeur AA, Liao CI, Casear MA, et al. The increasing incidence of stage IV cervical cancer in the USA: what factors are related? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:ijgc-2022-003728. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003728.

- Abdalla E, Habtemariam T, Fall S, et al. A comparative study of health disparities in cervical cancer mortality rates through time between Black and Caucasian women in Alabama and the US. Int J Stud Nurs. 2021;6:9-23. doi:10.20849/ijsn. v6i1.864.

- Bruegl AS, Emerson J, Tirumala K. Persistent disparities of cervical cancer among American Indians/Alaska natives: are we maximizing prevention tools? Gynecol Oncol. 2023;168:5661. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.11.007.

- Suk R, Hong YR, Rajan SS, et al. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force Guideline–Concordant cervical cancer screening rates and reasons for underscreening by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, rurality, and insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2143582. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2021.43582.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897.

- Nayar R, Chhieng DC, Crothers B, et al. Moving forward—the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors and beyond: implications and suggestions for laboratories. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020;9:291-303. doi:10.1016/j.jasc.2020.05.002.

- Cooley JJP, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov /statfacts/html/cervix.html

- Feldman S. Screening options for preventing cervical cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:879-880. doi:10.1001/ jamainternmed.2019.0298.

- ASCO Post Staff. FDA approves first HPV test for primary cervical cancer screening. ASCO Post. May 15, 2014. Accessed January 8, 2023. https://ascopost.com/issues/may-15-2014 /fda-approves-first-hpv-test-for-primary-cervical-cancer -screening/

- Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70296-0.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2.

- Kitchener HC, Almonte M, Thomson C, et al. HPV testing in combination with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical screening (ARTISTIC): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:672-682. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70156-1.

- Bulkmans NWJ, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year followup of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61450-0.

- Ogilvie GS, Van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7464.

- Gottschlich A, Gondara L, Smith LW, et al. Human papillomavirus‐based screening at extended intervals missed fewer cervical precancers than cytology in the HPV For Cervical Cancer (HPV FOCAL) trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:897-905. doi:10.1002/ijc.34039.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663672. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.076

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330-337. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669.

- Silver MI, Rositch AF, Burke AE, et al. Patient concerns about human papillomavirus testing and 5-year intervals in routine cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:317-329. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000638.

- Smith LW, Racey CS, Gondara L, et al. Women’s acceptability of and experience with primary human papillomavirus testing for cervical screening: HPV FOCAL trial cross-sectional online survey results. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e052084. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052084.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Clinical validation of p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology triage of HPV-positive women: results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:461-471. doi:10.1002/ijc.33812.

- Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, De Vuyst H, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4:e001351. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001351.

- Polman NJ, Ebisch RMF, Heideman DAM, et al. Performance of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of grade 2 or worse: a randomised, paired screen-positive, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:229-238. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30763-0.

- Winer RL, Lin J, Tiro JA, et al. Effect of mailed human papillomavirus test kits vs usual care reminders on cervical cancer screening uptake, precancer detection, and treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914729. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14729.

- Tiro JA, Betts AC, Kimbel K, et al. Understanding patients’ perspectives and information needs following a positive home human papillomavirus self-sampling kit result. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28:384-392. doi:10.1089/ jwh.2018.7070.

- Knauss T, Hansen BT, Pedersen K, et al. The cost-effectiveness of opt-in and send-to-all HPV self-sampling among long-term non-attenders to cervical cancer screening in Norway: the Equalscreen randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;168:39-47. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.10.027.

- ACOG committee opinion no. 809. Human papillomavirus vaccination: correction. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:345. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004680.

- St Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, et al. Younger age at initiation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016;89:327-333. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:13401348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1183-1190. doi:10.15585/ mmwr.mm7035a1.

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Australia. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2020. November 29, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://ncirs .org.au/sites/default/files/2021-11/NCIRS%20Annual%20 Immunisation%20Coverage%20Report%202020_FINAL.pdf

- Leung SOA, Feldman S. 2022 Update on cervical disease. OBG Manag. 2022;34(5):16-17, 22-24, 26, 28. doi:10.12788/ obgm.0197.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States Cancer Statistics: data visualizations. Trends: changes over time: cervix. Accessed January 8, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov /Cancer/USCS/#/Trends/

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660.

- Francoeur AA, Liao CI, Casear MA, et al. The increasing incidence of stage IV cervical cancer in the USA: what factors are related? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:ijgc-2022-003728. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003728.

- Abdalla E, Habtemariam T, Fall S, et al. A comparative study of health disparities in cervical cancer mortality rates through time between Black and Caucasian women in Alabama and the US. Int J Stud Nurs. 2021;6:9-23. doi:10.20849/ijsn. v6i1.864.

- Bruegl AS, Emerson J, Tirumala K. Persistent disparities of cervical cancer among American Indians/Alaska natives: are we maximizing prevention tools? Gynecol Oncol. 2023;168:5661. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.11.007.

- Suk R, Hong YR, Rajan SS, et al. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force Guideline–Concordant cervical cancer screening rates and reasons for underscreening by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, rurality, and insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2143582. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2021.43582.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897.

- Nayar R, Chhieng DC, Crothers B, et al. Moving forward—the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors and beyond: implications and suggestions for laboratories. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020;9:291-303. doi:10.1016/j.jasc.2020.05.002.

- Cooley JJP, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov /statfacts/html/cervix.html

- Feldman S. Screening options for preventing cervical cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:879-880. doi:10.1001/ jamainternmed.2019.0298.

- ASCO Post Staff. FDA approves first HPV test for primary cervical cancer screening. ASCO Post. May 15, 2014. Accessed January 8, 2023. https://ascopost.com/issues/may-15-2014 /fda-approves-first-hpv-test-for-primary-cervical-cancer -screening/

- Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70296-0.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2.

- Kitchener HC, Almonte M, Thomson C, et al. HPV testing in combination with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical screening (ARTISTIC): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:672-682. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70156-1.

- Bulkmans NWJ, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year followup of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61450-0.

- Ogilvie GS, Van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7464.

- Gottschlich A, Gondara L, Smith LW, et al. Human papillomavirus‐based screening at extended intervals missed fewer cervical precancers than cytology in the HPV For Cervical Cancer (HPV FOCAL) trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:897-905. doi:10.1002/ijc.34039.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663672. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.076

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330-337. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669.

- Silver MI, Rositch AF, Burke AE, et al. Patient concerns about human papillomavirus testing and 5-year intervals in routine cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:317-329. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000638.

- Smith LW, Racey CS, Gondara L, et al. Women’s acceptability of and experience with primary human papillomavirus testing for cervical screening: HPV FOCAL trial cross-sectional online survey results. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e052084. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052084.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Clinical validation of p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology triage of HPV-positive women: results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:461-471. doi:10.1002/ijc.33812.

- Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, De Vuyst H, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4:e001351. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001351.

- Polman NJ, Ebisch RMF, Heideman DAM, et al. Performance of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of grade 2 or worse: a randomised, paired screen-positive, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:229-238. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30763-0.

- Winer RL, Lin J, Tiro JA, et al. Effect of mailed human papillomavirus test kits vs usual care reminders on cervical cancer screening uptake, precancer detection, and treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914729. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14729.

- Tiro JA, Betts AC, Kimbel K, et al. Understanding patients’ perspectives and information needs following a positive home human papillomavirus self-sampling kit result. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28:384-392. doi:10.1089/ jwh.2018.7070.

- Knauss T, Hansen BT, Pedersen K, et al. The cost-effectiveness of opt-in and send-to-all HPV self-sampling among long-term non-attenders to cervical cancer screening in Norway: the Equalscreen randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;168:39-47. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.10.027.

- ACOG committee opinion no. 809. Human papillomavirus vaccination: correction. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:345. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004680.

- St Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, et al. Younger age at initiation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016;89:327-333. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:13401348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1183-1190. doi:10.15585/ mmwr.mm7035a1.

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Australia. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2020. November 29, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://ncirs .org.au/sites/default/files/2021-11/NCIRS%20Annual%20 Immunisation%20Coverage%20Report%202020_FINAL.pdf

- Leung SOA, Feldman S. 2022 Update on cervical disease. OBG Manag. 2022;34(5):16-17, 22-24, 26, 28. doi:10.12788/ obgm.0197.