User login

Case Report

A 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who was being treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with a dry cough, ataxia and falls, and vision loss. Physical examination was remarkable for diffuse crackles heard throughout the right lung and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Additionally, he had 4 pink mobile nodules on the left side of the forehead, right side of the chin, left submental area, and left postauricular scalp, which arose approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. The left postauricular lesion had been tender at times and had developed a crust. The cutaneous lesions were all smaller than 2 cm.

The patient had a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and was under the care of a dermatologist as an outpatient. His dermatologist had described him as an active gardener; he was noted to have healing abrasions on the forearms due to gardening raspberry bushes.

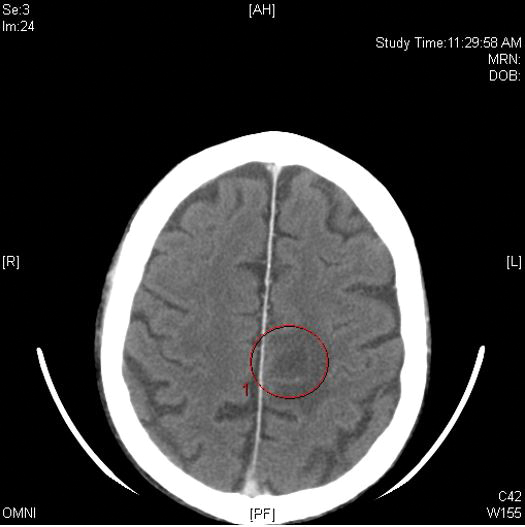

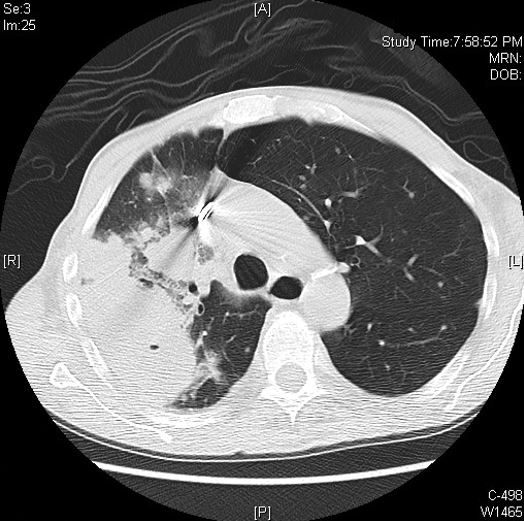

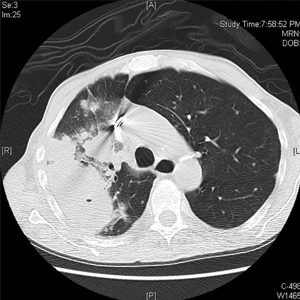

Computed tomography of the head revealed a 14-mm, ring-enhancing lesion in the left paramedian posterior frontal lobe with surrounding white matter vasogenic edema (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a peripheral mass on the right upper lobe measuring 6.3 cm at its greatest dimension (Figure 2).

Empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated. A dermatology consultation was placed by the hospitalist service; the consulting dermatologist noted that the patient had subepidermal nodules on the anterior thigh and abdomen, of which the patient had not been aware.

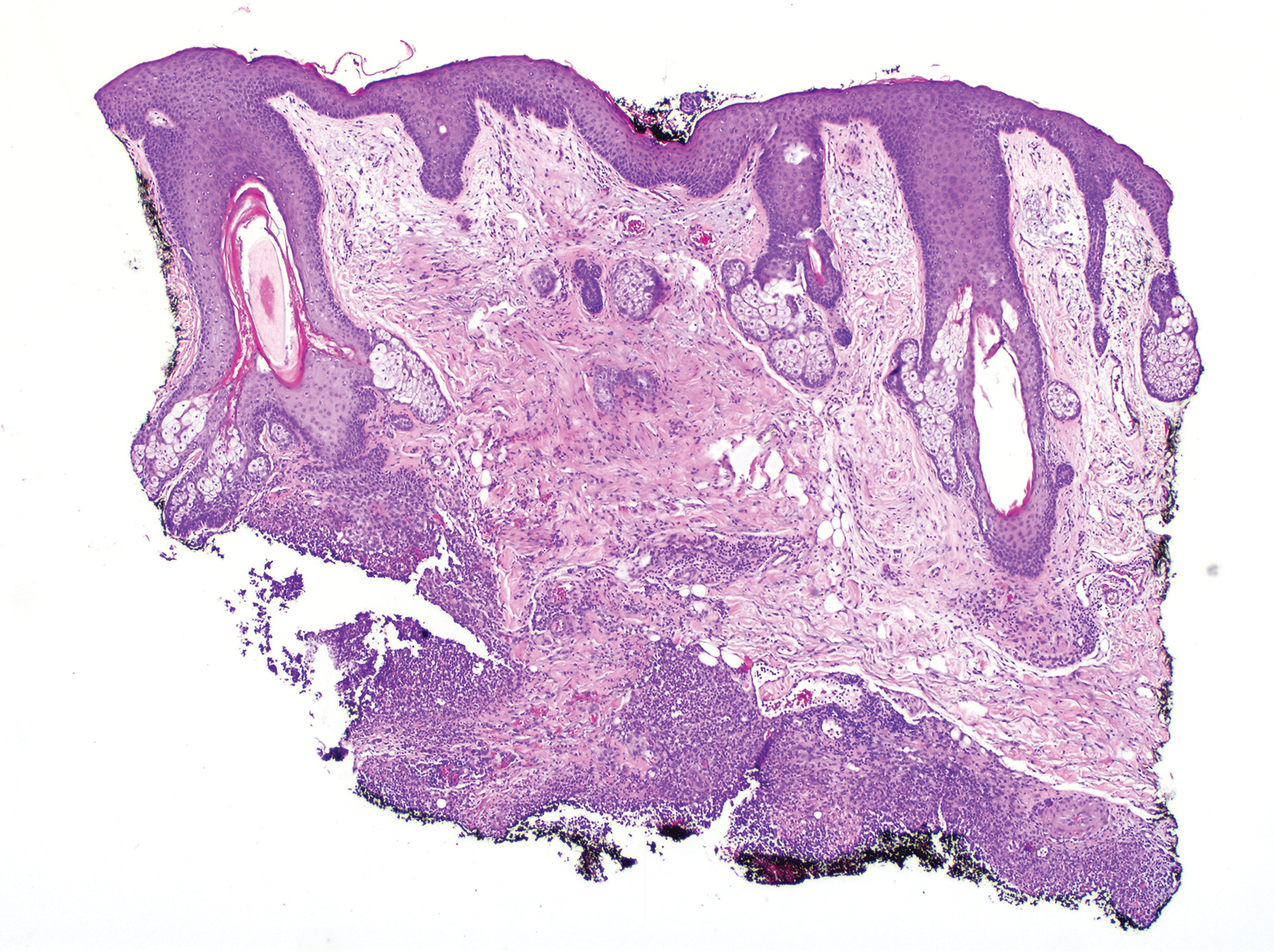

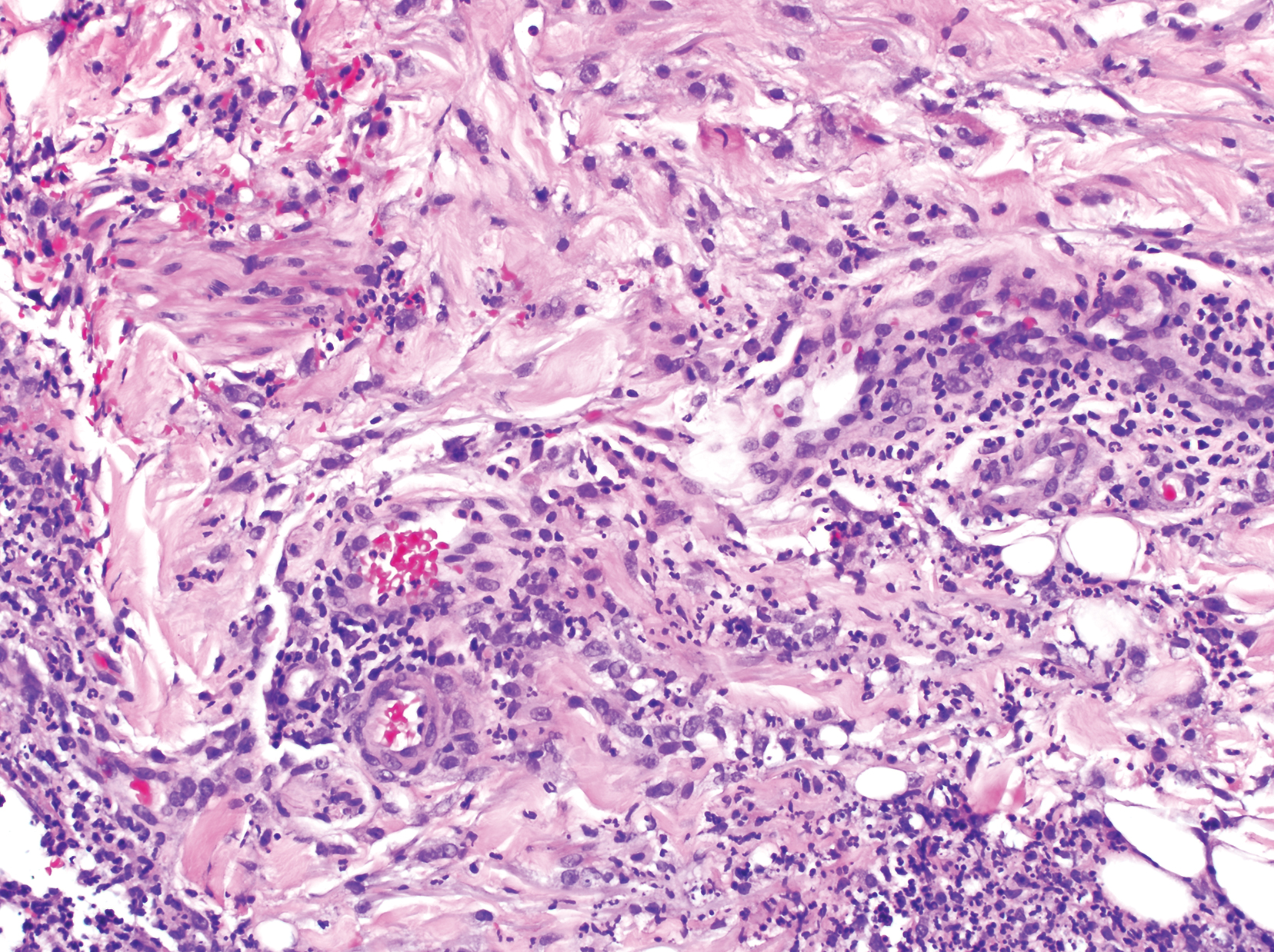

Clinically, the constellation of symptoms was thought to represent an infectious process or less likely metastatic malignancy. Biopsies of the nodule on the right side of the chin were performed and sent for culture and histologic examination. Sections from the anterior right chin showed compact orthokeratosis overlying a slightly spongiotic epidermis (Figure 3). Within the deep dermis, there was a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly neutrophils, with occasional eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 4).

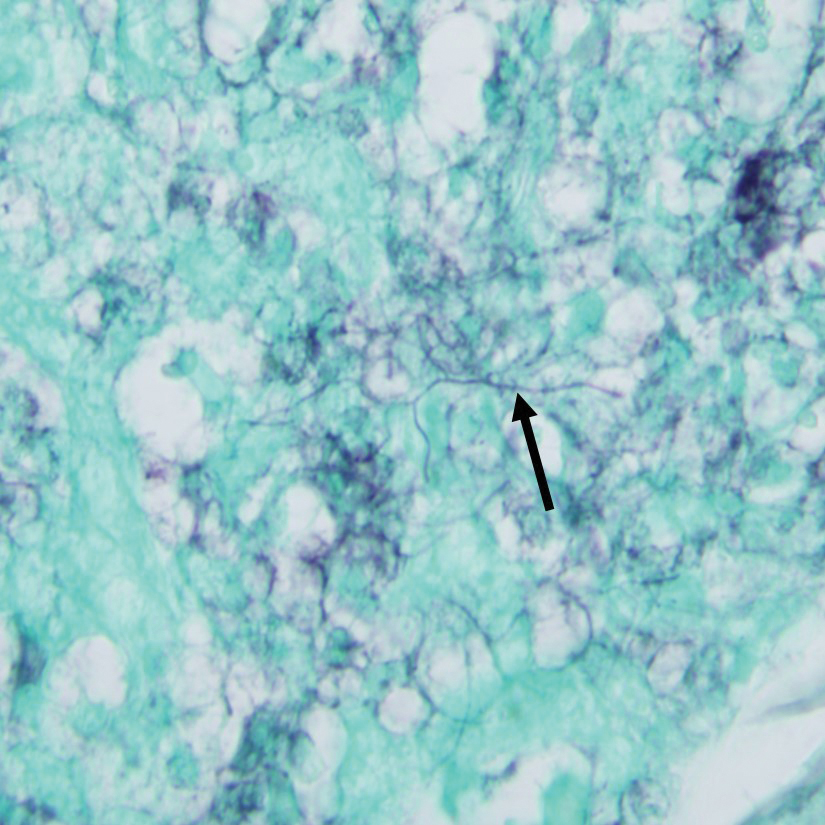

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

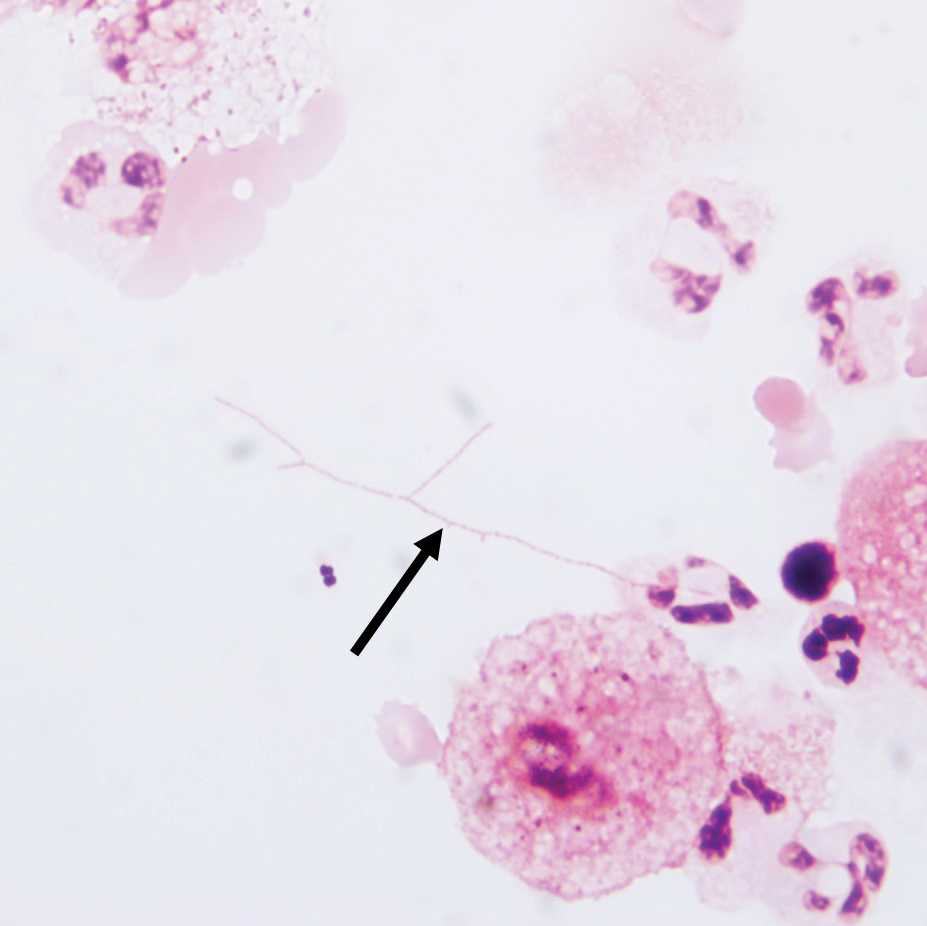

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8

Association With CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with profound immunodeficiency caused by quantitative and qualitative aberrations in both innate and adaptive immunity. This perturbation of the immune system predisposes the patient to infection.11,12 Early in the course of CLL, a patient develops neutropenia, which predisposes to bacterial infection; later, the patient develops a sustained B- and T-cell immunodeficiency that predisposes to opportunistic infection.13 Treatment-naïve patients with CLL are commonly diagnosed with respiratory and urinary tract infections.12 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with alemtuzumab or purine analogs have been reported to have the highest risk for major infection.14

Ibrutinib is a commonly used treatment of CLL because it induces apoptosis in B cells, which are abnormal in CLL. Ibrutinib functions by inhibiting the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway, which is essential in B-cell production and maintenance.15 Studies have reported a high rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients14,16; salvage ibrutinib therapy has been associated with higher infection risk than primary ibrutinib therapy.16,17 Long-term follow-up studies have shown a decreased rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL after 2 years or longer of treatment, suggesting a reconstitution of normal B cells and humoral immunity with longer ibrutinib therapy.16,17

Many infections have been identified in association with ibrutinib therapy, including invasive aspergillosis, disseminated fusariosis, cerebral mucormycosis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.18-22 Disseminated nocardiosis has been reported in a few patients with CLL, though the treatment they received for CLL varied from case to case.23-25

Identification and Treatment

Clinical and microscopic identification of Nocardia organisms can be exceedingly difficult. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis clinically presents as tumors or nodules that often have a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. In disease that disseminates to skin, nocardiosis presents as vesiculopustules or abscesses. The biopsy specimen most often shows a dense dermal and subcutaneous infiltrate of neutrophils with abscess formation. Long-standing lesions might show chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.

The appearance of Nocardia organisms is quite subtle on hematoxylin and eosin staining and can be easily missed. Special stains, such as Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains as well as stains for acid-fast organisms, can be invaluable in diagnosing this disease. Biopsy in immunocompromised patients when nocardiosis is part of the differential diagnosis requires extra attention because the organisms can be gram variable and only partially acid fast, as was the case in our patient. Organisms typically will be positive with silver stains.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole typically is the first-line treatment of nocardiosis. Although prognosis is excellent when disease is confined to skin, disseminated infection has 25% mortality.8 Diagnosticians should maintain a high index of suspicion for the disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, because clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific.

Conclusion

Our patient’s primary risk factor for nocardiosis was his immunocompromised state. In addition, he was an avid gardener, which increased his risk for exposure to the microorganism. Given the timing of disease progression, our case most likely represents primary cutaneous nocardiosis with dissemination to brain, lungs, and other organs, leading to death, and serves as a reminder to dermatologists and pathologists to establish a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with an infectious process in immunocompromised patients.

- Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Grau Pérez M, Casabella Pernas A, de la Rosa Del Rey MDP, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a pitfall in the diagnosis of skin infection. Infection. 2017;45:927-928.

- Oda R, Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2017;56:469-470.

- Jiang Y, Huang A, Fang Q. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3339-3346.

- Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, et al. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- Kim MS, Choi H, Choi KC, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia vinacea: first case in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:812-814.

- Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ. Diagnostic Pathology. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

- Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- Bosamiya SS, Vaishnani JB, Momin AM. Sporotrichoid nocardiosis with cutaneous dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:535.

- Riches JC, Gribben JG. Understanding the immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential clinical implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:207-235.

- Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126:573-581.

- Tadmor T, Welslau M, Hus I. A review of the infection pathogenesis and prophylaxis recommendations in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:57-70.

- Williams AM, Baran AM, Meacham PJ, et al. Analysis of the risk of infection in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel therapies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:625-632.

- Dias AL, Jain D. Ibrutinib: a new frontier in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2013;11:265-271.

- Sun C, Tian X, Lee YS, et al. Partial reconstitution of humoral immunity and fewer infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;126:2213-2219.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2497-2506.

- Arthurs B, Wunderle K, Hsu M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis related to ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;21:27-29.

- Chan TS, Au-Yeung R, Chim CS, et al. Disseminated fusarium infection after ibrutinib therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:871-872.

- Farid S, AbuSaleh O, Liesman R, et al. Isolated cerebral mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor pusillus [published online October 4, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. pii:bcr-2017-221473.

- Okamoto K, Proia LA, Demarais PL. Disseminated cryptococcal disease in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia on ibrutinib. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:4642831.

- Ahn IE, Jerussi T, Farooqui M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in previously untreated patients with CLL on single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2016;128:1940-1943.

- Roberts AL, Davidson RM, Freifeld AG, et al. Nocardia arthritidis as a cause of disseminated nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. IDCases. 2016;6:68-71.

- Rámila E, Martino R, Santamaría A, et al. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone as the initial sign of central nervous system progression of nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 1999;84:1155-1156.

- Phillips WB, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Nocardia choroidal abscess. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:694-696.

Case Report

A 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who was being treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with a dry cough, ataxia and falls, and vision loss. Physical examination was remarkable for diffuse crackles heard throughout the right lung and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Additionally, he had 4 pink mobile nodules on the left side of the forehead, right side of the chin, left submental area, and left postauricular scalp, which arose approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. The left postauricular lesion had been tender at times and had developed a crust. The cutaneous lesions were all smaller than 2 cm.

The patient had a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and was under the care of a dermatologist as an outpatient. His dermatologist had described him as an active gardener; he was noted to have healing abrasions on the forearms due to gardening raspberry bushes.

Computed tomography of the head revealed a 14-mm, ring-enhancing lesion in the left paramedian posterior frontal lobe with surrounding white matter vasogenic edema (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a peripheral mass on the right upper lobe measuring 6.3 cm at its greatest dimension (Figure 2).

Empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated. A dermatology consultation was placed by the hospitalist service; the consulting dermatologist noted that the patient had subepidermal nodules on the anterior thigh and abdomen, of which the patient had not been aware.

Clinically, the constellation of symptoms was thought to represent an infectious process or less likely metastatic malignancy. Biopsies of the nodule on the right side of the chin were performed and sent for culture and histologic examination. Sections from the anterior right chin showed compact orthokeratosis overlying a slightly spongiotic epidermis (Figure 3). Within the deep dermis, there was a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly neutrophils, with occasional eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 4).

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8

Association With CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with profound immunodeficiency caused by quantitative and qualitative aberrations in both innate and adaptive immunity. This perturbation of the immune system predisposes the patient to infection.11,12 Early in the course of CLL, a patient develops neutropenia, which predisposes to bacterial infection; later, the patient develops a sustained B- and T-cell immunodeficiency that predisposes to opportunistic infection.13 Treatment-naïve patients with CLL are commonly diagnosed with respiratory and urinary tract infections.12 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with alemtuzumab or purine analogs have been reported to have the highest risk for major infection.14

Ibrutinib is a commonly used treatment of CLL because it induces apoptosis in B cells, which are abnormal in CLL. Ibrutinib functions by inhibiting the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway, which is essential in B-cell production and maintenance.15 Studies have reported a high rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients14,16; salvage ibrutinib therapy has been associated with higher infection risk than primary ibrutinib therapy.16,17 Long-term follow-up studies have shown a decreased rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL after 2 years or longer of treatment, suggesting a reconstitution of normal B cells and humoral immunity with longer ibrutinib therapy.16,17

Many infections have been identified in association with ibrutinib therapy, including invasive aspergillosis, disseminated fusariosis, cerebral mucormycosis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.18-22 Disseminated nocardiosis has been reported in a few patients with CLL, though the treatment they received for CLL varied from case to case.23-25

Identification and Treatment

Clinical and microscopic identification of Nocardia organisms can be exceedingly difficult. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis clinically presents as tumors or nodules that often have a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. In disease that disseminates to skin, nocardiosis presents as vesiculopustules or abscesses. The biopsy specimen most often shows a dense dermal and subcutaneous infiltrate of neutrophils with abscess formation. Long-standing lesions might show chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.

The appearance of Nocardia organisms is quite subtle on hematoxylin and eosin staining and can be easily missed. Special stains, such as Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains as well as stains for acid-fast organisms, can be invaluable in diagnosing this disease. Biopsy in immunocompromised patients when nocardiosis is part of the differential diagnosis requires extra attention because the organisms can be gram variable and only partially acid fast, as was the case in our patient. Organisms typically will be positive with silver stains.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole typically is the first-line treatment of nocardiosis. Although prognosis is excellent when disease is confined to skin, disseminated infection has 25% mortality.8 Diagnosticians should maintain a high index of suspicion for the disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, because clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific.

Conclusion

Our patient’s primary risk factor for nocardiosis was his immunocompromised state. In addition, he was an avid gardener, which increased his risk for exposure to the microorganism. Given the timing of disease progression, our case most likely represents primary cutaneous nocardiosis with dissemination to brain, lungs, and other organs, leading to death, and serves as a reminder to dermatologists and pathologists to establish a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with an infectious process in immunocompromised patients.

Case Report

A 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who was being treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with a dry cough, ataxia and falls, and vision loss. Physical examination was remarkable for diffuse crackles heard throughout the right lung and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Additionally, he had 4 pink mobile nodules on the left side of the forehead, right side of the chin, left submental area, and left postauricular scalp, which arose approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. The left postauricular lesion had been tender at times and had developed a crust. The cutaneous lesions were all smaller than 2 cm.

The patient had a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and was under the care of a dermatologist as an outpatient. His dermatologist had described him as an active gardener; he was noted to have healing abrasions on the forearms due to gardening raspberry bushes.

Computed tomography of the head revealed a 14-mm, ring-enhancing lesion in the left paramedian posterior frontal lobe with surrounding white matter vasogenic edema (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a peripheral mass on the right upper lobe measuring 6.3 cm at its greatest dimension (Figure 2).

Empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated. A dermatology consultation was placed by the hospitalist service; the consulting dermatologist noted that the patient had subepidermal nodules on the anterior thigh and abdomen, of which the patient had not been aware.

Clinically, the constellation of symptoms was thought to represent an infectious process or less likely metastatic malignancy. Biopsies of the nodule on the right side of the chin were performed and sent for culture and histologic examination. Sections from the anterior right chin showed compact orthokeratosis overlying a slightly spongiotic epidermis (Figure 3). Within the deep dermis, there was a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly neutrophils, with occasional eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 4).

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8

Association With CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with profound immunodeficiency caused by quantitative and qualitative aberrations in both innate and adaptive immunity. This perturbation of the immune system predisposes the patient to infection.11,12 Early in the course of CLL, a patient develops neutropenia, which predisposes to bacterial infection; later, the patient develops a sustained B- and T-cell immunodeficiency that predisposes to opportunistic infection.13 Treatment-naïve patients with CLL are commonly diagnosed with respiratory and urinary tract infections.12 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with alemtuzumab or purine analogs have been reported to have the highest risk for major infection.14

Ibrutinib is a commonly used treatment of CLL because it induces apoptosis in B cells, which are abnormal in CLL. Ibrutinib functions by inhibiting the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway, which is essential in B-cell production and maintenance.15 Studies have reported a high rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients14,16; salvage ibrutinib therapy has been associated with higher infection risk than primary ibrutinib therapy.16,17 Long-term follow-up studies have shown a decreased rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL after 2 years or longer of treatment, suggesting a reconstitution of normal B cells and humoral immunity with longer ibrutinib therapy.16,17

Many infections have been identified in association with ibrutinib therapy, including invasive aspergillosis, disseminated fusariosis, cerebral mucormycosis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.18-22 Disseminated nocardiosis has been reported in a few patients with CLL, though the treatment they received for CLL varied from case to case.23-25

Identification and Treatment

Clinical and microscopic identification of Nocardia organisms can be exceedingly difficult. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis clinically presents as tumors or nodules that often have a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. In disease that disseminates to skin, nocardiosis presents as vesiculopustules or abscesses. The biopsy specimen most often shows a dense dermal and subcutaneous infiltrate of neutrophils with abscess formation. Long-standing lesions might show chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.

The appearance of Nocardia organisms is quite subtle on hematoxylin and eosin staining and can be easily missed. Special stains, such as Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains as well as stains for acid-fast organisms, can be invaluable in diagnosing this disease. Biopsy in immunocompromised patients when nocardiosis is part of the differential diagnosis requires extra attention because the organisms can be gram variable and only partially acid fast, as was the case in our patient. Organisms typically will be positive with silver stains.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole typically is the first-line treatment of nocardiosis. Although prognosis is excellent when disease is confined to skin, disseminated infection has 25% mortality.8 Diagnosticians should maintain a high index of suspicion for the disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, because clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific.

Conclusion

Our patient’s primary risk factor for nocardiosis was his immunocompromised state. In addition, he was an avid gardener, which increased his risk for exposure to the microorganism. Given the timing of disease progression, our case most likely represents primary cutaneous nocardiosis with dissemination to brain, lungs, and other organs, leading to death, and serves as a reminder to dermatologists and pathologists to establish a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with an infectious process in immunocompromised patients.

- Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Grau Pérez M, Casabella Pernas A, de la Rosa Del Rey MDP, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a pitfall in the diagnosis of skin infection. Infection. 2017;45:927-928.

- Oda R, Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2017;56:469-470.

- Jiang Y, Huang A, Fang Q. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3339-3346.

- Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, et al. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- Kim MS, Choi H, Choi KC, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia vinacea: first case in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:812-814.

- Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ. Diagnostic Pathology. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

- Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- Bosamiya SS, Vaishnani JB, Momin AM. Sporotrichoid nocardiosis with cutaneous dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:535.

- Riches JC, Gribben JG. Understanding the immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential clinical implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:207-235.

- Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126:573-581.

- Tadmor T, Welslau M, Hus I. A review of the infection pathogenesis and prophylaxis recommendations in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:57-70.

- Williams AM, Baran AM, Meacham PJ, et al. Analysis of the risk of infection in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel therapies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:625-632.

- Dias AL, Jain D. Ibrutinib: a new frontier in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2013;11:265-271.

- Sun C, Tian X, Lee YS, et al. Partial reconstitution of humoral immunity and fewer infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;126:2213-2219.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2497-2506.

- Arthurs B, Wunderle K, Hsu M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis related to ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;21:27-29.

- Chan TS, Au-Yeung R, Chim CS, et al. Disseminated fusarium infection after ibrutinib therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:871-872.

- Farid S, AbuSaleh O, Liesman R, et al. Isolated cerebral mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor pusillus [published online October 4, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. pii:bcr-2017-221473.

- Okamoto K, Proia LA, Demarais PL. Disseminated cryptococcal disease in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia on ibrutinib. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:4642831.

- Ahn IE, Jerussi T, Farooqui M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in previously untreated patients with CLL on single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2016;128:1940-1943.

- Roberts AL, Davidson RM, Freifeld AG, et al. Nocardia arthritidis as a cause of disseminated nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. IDCases. 2016;6:68-71.

- Rámila E, Martino R, Santamaría A, et al. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone as the initial sign of central nervous system progression of nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 1999;84:1155-1156.

- Phillips WB, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Nocardia choroidal abscess. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:694-696.

- Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Grau Pérez M, Casabella Pernas A, de la Rosa Del Rey MDP, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a pitfall in the diagnosis of skin infection. Infection. 2017;45:927-928.

- Oda R, Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2017;56:469-470.

- Jiang Y, Huang A, Fang Q. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3339-3346.

- Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, et al. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- Kim MS, Choi H, Choi KC, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia vinacea: first case in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:812-814.

- Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ. Diagnostic Pathology. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

- Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- Bosamiya SS, Vaishnani JB, Momin AM. Sporotrichoid nocardiosis with cutaneous dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:535.

- Riches JC, Gribben JG. Understanding the immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential clinical implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:207-235.

- Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126:573-581.

- Tadmor T, Welslau M, Hus I. A review of the infection pathogenesis and prophylaxis recommendations in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:57-70.

- Williams AM, Baran AM, Meacham PJ, et al. Analysis of the risk of infection in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel therapies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:625-632.

- Dias AL, Jain D. Ibrutinib: a new frontier in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2013;11:265-271.

- Sun C, Tian X, Lee YS, et al. Partial reconstitution of humoral immunity and fewer infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;126:2213-2219.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2497-2506.

- Arthurs B, Wunderle K, Hsu M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis related to ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;21:27-29.

- Chan TS, Au-Yeung R, Chim CS, et al. Disseminated fusarium infection after ibrutinib therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:871-872.

- Farid S, AbuSaleh O, Liesman R, et al. Isolated cerebral mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor pusillus [published online October 4, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. pii:bcr-2017-221473.

- Okamoto K, Proia LA, Demarais PL. Disseminated cryptococcal disease in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia on ibrutinib. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:4642831.

- Ahn IE, Jerussi T, Farooqui M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in previously untreated patients with CLL on single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2016;128:1940-1943.

- Roberts AL, Davidson RM, Freifeld AG, et al. Nocardia arthritidis as a cause of disseminated nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. IDCases. 2016;6:68-71.

- Rámila E, Martino R, Santamaría A, et al. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone as the initial sign of central nervous system progression of nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 1999;84:1155-1156.

- Phillips WB, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Nocardia choroidal abscess. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:694-696.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should consider a broad differential when dealing with infectious diseases in immunocompromised patients.

- Primary cutaneous nocardiosis classically presents as tumors or nodules with a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. Vesiculopustules and abscesses are seen in disseminated disease, which usually involves the skin, lungs, and/or central nervous system.

- Nocardia species are characteristically gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle branching filaments.

- When nocardiosis is in the differential, special care should be taken, as organisms can be gram variable or only partially acid fast. Gram, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and acid-fast staining may be essential to making the diagnosis.