User login

We thought they were gone, but they’ve returned: diseases once considered “vintage bugs” that were common in as late as the mid-20th century. In the past these diseases killed one in three people younger than 20 who had survived an infancy during which many of their contemporaries died.1

“When you think about disease states, you think about some that are gone from the world,” says Erin Stucky, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the University of California, San Diego, “but there are very few truly gone from the world.”

Some of the major infectious diseases that hospitalists may [still] see are pertussis (whooping cough), measles, and mumps, but scarlet fever and varicella (chicken pox) also endure—not to mention those occurrences of polio around the country that epidemiologists and infectious diseases specialists are monitoring closely. Rickets, a vitamin-D-deficiency-related disease also thought to be a relic of the 18th century, is showing up in certain patient populations—and not exclusively in infants and children.

This is a crossover clinical issue, our pediatric hospitalists say, and thus one to which their hospitalist partners who treat adult patients must also remain alert.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

Despite vaccination protocols, pediatric hospitalists continue to see whooping cough in young infants. (See Figure 1, p. 39.) Even with treatment, the damage can be severe, and the length of stay (LOS) is prolonged compared with those of most other patients with complex illnesses. “Vaccine fatigue” means that immunization lasts only until adolescence or early adulthood, at which time they need appropriate boosters. If the patient hasn’t receive boosters, the initial immunization loses its effectiveness; unprotected, they can be infected with the disease, though sometimes not badly enough for them to seek care. When they do, the diagnosis is often community-acquired mild pneumonia or a more traditional bronchitis. Either by accident or because the physician has given it thought, those illnesses are treated with a macrolide drug, which is also—coincidentally and serendipitously—the drug of choice for pertussis. But many remain carriers because they are not accurately diagnosed or never seek care.

“There is a huge reservoir of people carrying pertussis, particularly [in] the adolescent and adult population[s],” says Alison Holmes, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Concord Hospital, N.H. “And the babies who get really sick from it are the under two- to three-month group who have not yet been immunized or have just been immunized. Because it is so rampant in the adolescent and adult community, those children can still get sick.”

“Unfortunately,” says Dr. Stucky, “what’s happening is that if physicians are not thinking pertussis, they don’t talk about pertussis to that adult patient who … is either around children or has children in the home. So they don’t know to tell that person to watch for these same signs and symptoms in that young infant, who then could have a much more severe outcome from getting [the infection].”

As with most patients who contract illnesses, these patients may never have heard of the disease and unless educated may not understand the implications of the diagnosis. They might realize their disease could spread to family members, “but most people don’t absorb that information and use that information thoughtfully,” says Dr. Stucky. The onus is, therefore, on the physician to warn adult patients specifically about the serious danger that exists for infants in the two- to three-month-old group, who may not have been vaccinated or whose single-vaccination immunity is not adequate protection against the disease.

While the numbers in babies appear to be what they have always been, the incidence has grown in the teen years and even later into adulthood. This is more likely the result of increased testing for pertussis, as opposed to being only due to a true resurgence. Data from studies of adults with prolonged cough revealed that 20% to 25% have serologic evidence of recent pertussis infection.2 Adults are the major reservoir of infection, and infection spreads quickly in a population in a closed environment where droplets spread easily person to person.5

For both teens and adults, testing and immunization with the newly recommended DTaP (diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis)—as opposed to the more limited Td—can help upgrade immunity. Although a patient can recover from pertussis on his or her own within one to two weeks following treatment, the intent of treatment is primarily to limit the spread of disease to others.4-7

The problem when adults get pertussis, says Dr. Holmes, who is also an assistant professor of community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H., “is that they often don’t show up complaining about this horrible paroxysmal coughing until they’re about three or four weeks into the illness, and it hasn’t gone away. You go for hours and hours feeling completely fine and wonderful, and why would you bother going to the doctor?”

Babies are most at risk, however. “They often don’t have the energy or the muscle strength, so they just stop breathing instead,” she says.

Mark Dworkin, MD, MPH, TM, the state epidemiologist and team leader for the Rapid Response Team at the Illinois Department of Public Health, is active in outbreak investigation. He wrote a compelling argument for maintaining a high index of suspicion when physicians see adolescent and adult patients who have a cough that has lasted more than two weeks.4

It has been estimated that more than one million cases of pertussis occur in the United States each year; that number has continued to grow for 20 years. From 1990 to 2001, the incidence of pertussis in adults increased by 400%. But many physicians believe that pertussis is only a pediatric illness. A survey of internists in Washington state showed that only 38% of respondents knew about the risk of vaccine fatigue, and just 36% knew that the nasopharyngeal swab is the preferred method for sample collection. Public health professionals were also concerned with the finding that too many pediatricians and nonpediatricians (43% and 41%, respectively) were not able to define a reportable case.

The first challenge that faces internists, writes Dr. Dworkin, is recognizing pertussis, which in some cases presents with mild symptoms; some adults won’t even have a cough.4 But at the other end of the disease spectrum, symptoms may be as brutal as bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage or rib fracture due to convulsive coughing. In any case, what goes unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated becomes a particularly serious risk for vulnerable infants. Once pertussis is identified, positive results on polymerase chain reaction or culture can help convince skeptical colleagues who may still believe pertussis is exclusively a childhood disease—and a vintage one at that.

“What we in pediatrics champion … is for [these immunizations] to help the young child; the less disease we have out there, the better off we’re going to eventually be,” says Dr. Stucky, who projects that, within just a few years, Tdap vaccinations for adolescents and adults up to age 64 might lead to a reduction of infection in the three-month-old group.6

Measles and Mumps

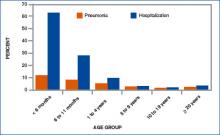

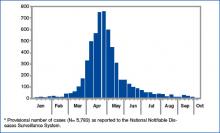

From January 1 to October 7, 2006, 45 states and the District of Columbia reported 5,783 confirmed or probable mumps cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (See Figures 2 and 3, above.)8 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) announced that continuing data from surveillance reports meant that healthcare workers should remain alert to suspected cases, conduct appropriate laboratory testing, and use every opportunity to ensure adequate immunity, particularly among populations at high risk.7

In contrast to the circumstances with pertussis, with mumps “there have been pockets of people who have either chosen not to immunize their child[ren], or their child[ren] get exposed to it somehow,” says Dr. Stucky, “and although they might be immunized, they might not have had a good response.” In an environment such as a school, “where one child can cough on a few and then cough on a few [more],” there is an environment where the infection can spread rampantly.

With mumps and measles, these could be called true outbreaks, such as the classic example that occurred in Kansas 18 years ago or the epidemic that disseminated from a college campus in Iowa in the spring of 2006, which originated from only two airline passengers on nine different flights within one week.8

College dorms and cafeterias can be treacherous breeding grounds for pathogens, and this generation of college students is susceptible for a few reasons. For one, in the late 1980s, when they were infants, the vaccine schedule was changed; the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine was upgraded from one dose to two—and not all children received the two doses.

The unimmunized who are exposed to measles and mumps remain at highest risk for spreading the disease. Although in 2005, 76%-79% of children aged 19-35 months received the entire recommended series of shots against whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenza type B, that still means that 21%-24% of the children—or potentially one out of five kids—did not.9

Other factors causing low levels of immunization include parents’ Internet-fueled fears of links to autism; immigrants crossing U.S. borders from Mexico or other countries where immunization is not standardized; religious and philosophical reasons; and international travel.10

“When young adults travel internationally [to places] where they are exposed to young children and adults who have never been immunized,” that’s a big risk, says Dr. Stucky. “All it would take is one [infected] student coming into a dorm and passing it around [to others with lapsed coverage or no immunization for the disease].” And while providers may think of travelers being exposed to diseases such as malaria and typhoid fever in developing countries, “in reality, a lot of the common things we’re immunizing for in our country are not immunized for in other countries, and those can be brought back.”

Rickets

The incidence of rickets is increasing, especially in black and Hispanic children and particularly in the north.11,12 Epidemiologists trace the rise to an increase in breast-feeding (good for immunity, but breast milk lacks substantial vitamin D), overuse of sunscreen or lack of exposure to sunlight, and changes in physician recommendations for vitamin supplementation. The effects of rickets alone can be profound, but other long-term consequences of vitamin D deficiency may include type I diabetes, cancer (especially of the prostate), and osteoporosis.12

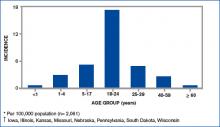

In the past few decades, physicians have been less likely to recommend vitamin D supplementation for babies, and an interesting study by Davenport and colleagues correlates the year of medical school completion to that decline as well as substantial variability as to the age at which supplement use is begun.12 (See Figures 4a and 4b, left.)

“Most of the cases I have run into have been in [recent] African immigrants, where the mothers stay covered and they are vitamin D deficient,” says Dr. Holmes. “It’s wonderful that they culturally breast-feed, but they come to the U.S., and they’re pretty afraid to go outside in a new society.”

Varicella (Chicken Pox)

Varicella was removed from the CDC’s national notifiable disease list in 1981, but in 1995 a varicella vaccine was recommended for routine childhood vaccination.13 Before the licensure of that vaccine, varicella was a universal childhood disease in the U.S., causing 4 million cases, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths every year.14 In 2002, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists recommended that varicella be included in the National Notifiable Surveillance System by 2003 and that case-based surveillance in all states be established by 2005.13 CDC’s ACIP recommended in 2006 that a routine second dose of varicella vaccine be given to children between the ages of four and six years old.

Contracting chicken pox as an adult is a much more morbid occurrence than catching it as a child. Although varicella is not life threatening (as are diphtheria, tetanus, and measles) or sterility-causing (as is mumps), when the vaccine was approved, some pediatricians, including Dr. Stucky, became concerned that “now we’re creating a population that has never seen the wild-type varicella virus, and what does that mean? Were we just delaying something into an age category where people will get sicker?” Recognizing varicella, therefore, is critical even for hospitalists who treat adults.

Conclusion

“I’ve seen mumps, measles, varicella, pertussis,” says Dr. Stucky, “but our adult [hospitalist] partners hadn’t.” She encourages her colleagues who treat adult populations “to read and be diligent. These diseases can exist in adults, or even in children who were once vaccinated, and all hospitalists need to know “what to do, how to treat them, and [that] the consequences in adults are hands down worse than in children.”

Dr. Stucky believes hospitalists who treat adults would do well to consult physicians who practiced in the 1950s because they understand the history as well as clinical signs and symptoms of these diseases; she says, “For the hospitalist who treats adults, these are the equivalent of emerging infectious diseases.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Carmichael M. 'Vintage' bugs return. Newsweek. May 1, 2006:Vol. 147, p. 38. Available at: www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12440796/site/newsweek/. Accessed on November 29, 2006.

- Herwaldt LA. Pertussis in adults. What physicians need to know. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1510-1512.

- Schafer S, Gillette H, Hedberg K, et al. A community-wide pertussis outbreak: an argument for universal booster vaccination. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1317-1321.

- Dworkin MS. Adults are whooping, but are internists listening? Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 17;142(10):832-835. Available at: www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/142/10/832.pdf. Accessed on November 19, 2006.

- Gregory DS. Pertussis: a disease affecting all ages. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1;74(3):420-426.

- Finger R, Shoemaker J. Preventing pertussis in infants by vaccinating adults. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1;74(3):382.

- Broder KR, Cortese MM, Iskander JK, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-34.

- MMWR. Brief report: update: mumps activity—United States, January 1-October 7, 2006. MMWR. 2006 Oct 27;55(42):1152-1153.

- National Briefing: Science and health: race gap closes in vaccinations, U.S. says. New York Times. September 15, 2006.

- Calandrillo SP. Vanishing vaccinations: why are so many Americans opting out of vaccinating their children? Univ Mich J Law Reform. 2004 Winter;37(2):353-440.

- Kreiter SR, Schwartz RP, Kirkman HN Jr, et al. Nutritional rickets in African American breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 2000 Aug;137(2):153-157.

- Davenport ML, Uckun A, Calikoglu AS. Pediatrician patterns of prescribing vitamin supplementation for infants: do they contribute to rickets? Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(1 Pt 1):179-180.

- MMWR. Varicella surveillance practices—United States, 2004. MMWR. 2006 Oct 19;55:1126-1129.

- Seward JF, Watson BM, Peterson CL, et al. Varicella disease after introduction of varicella vaccine in the United States, 1995-2000. JAMA. 2002 Feb 6;287(5):606-611.

We thought they were gone, but they’ve returned: diseases once considered “vintage bugs” that were common in as late as the mid-20th century. In the past these diseases killed one in three people younger than 20 who had survived an infancy during which many of their contemporaries died.1

“When you think about disease states, you think about some that are gone from the world,” says Erin Stucky, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the University of California, San Diego, “but there are very few truly gone from the world.”

Some of the major infectious diseases that hospitalists may [still] see are pertussis (whooping cough), measles, and mumps, but scarlet fever and varicella (chicken pox) also endure—not to mention those occurrences of polio around the country that epidemiologists and infectious diseases specialists are monitoring closely. Rickets, a vitamin-D-deficiency-related disease also thought to be a relic of the 18th century, is showing up in certain patient populations—and not exclusively in infants and children.

This is a crossover clinical issue, our pediatric hospitalists say, and thus one to which their hospitalist partners who treat adult patients must also remain alert.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

Despite vaccination protocols, pediatric hospitalists continue to see whooping cough in young infants. (See Figure 1, p. 39.) Even with treatment, the damage can be severe, and the length of stay (LOS) is prolonged compared with those of most other patients with complex illnesses. “Vaccine fatigue” means that immunization lasts only until adolescence or early adulthood, at which time they need appropriate boosters. If the patient hasn’t receive boosters, the initial immunization loses its effectiveness; unprotected, they can be infected with the disease, though sometimes not badly enough for them to seek care. When they do, the diagnosis is often community-acquired mild pneumonia or a more traditional bronchitis. Either by accident or because the physician has given it thought, those illnesses are treated with a macrolide drug, which is also—coincidentally and serendipitously—the drug of choice for pertussis. But many remain carriers because they are not accurately diagnosed or never seek care.

“There is a huge reservoir of people carrying pertussis, particularly [in] the adolescent and adult population[s],” says Alison Holmes, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Concord Hospital, N.H. “And the babies who get really sick from it are the under two- to three-month group who have not yet been immunized or have just been immunized. Because it is so rampant in the adolescent and adult community, those children can still get sick.”

“Unfortunately,” says Dr. Stucky, “what’s happening is that if physicians are not thinking pertussis, they don’t talk about pertussis to that adult patient who … is either around children or has children in the home. So they don’t know to tell that person to watch for these same signs and symptoms in that young infant, who then could have a much more severe outcome from getting [the infection].”

As with most patients who contract illnesses, these patients may never have heard of the disease and unless educated may not understand the implications of the diagnosis. They might realize their disease could spread to family members, “but most people don’t absorb that information and use that information thoughtfully,” says Dr. Stucky. The onus is, therefore, on the physician to warn adult patients specifically about the serious danger that exists for infants in the two- to three-month-old group, who may not have been vaccinated or whose single-vaccination immunity is not adequate protection against the disease.

While the numbers in babies appear to be what they have always been, the incidence has grown in the teen years and even later into adulthood. This is more likely the result of increased testing for pertussis, as opposed to being only due to a true resurgence. Data from studies of adults with prolonged cough revealed that 20% to 25% have serologic evidence of recent pertussis infection.2 Adults are the major reservoir of infection, and infection spreads quickly in a population in a closed environment where droplets spread easily person to person.5

For both teens and adults, testing and immunization with the newly recommended DTaP (diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis)—as opposed to the more limited Td—can help upgrade immunity. Although a patient can recover from pertussis on his or her own within one to two weeks following treatment, the intent of treatment is primarily to limit the spread of disease to others.4-7

The problem when adults get pertussis, says Dr. Holmes, who is also an assistant professor of community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H., “is that they often don’t show up complaining about this horrible paroxysmal coughing until they’re about three or four weeks into the illness, and it hasn’t gone away. You go for hours and hours feeling completely fine and wonderful, and why would you bother going to the doctor?”

Babies are most at risk, however. “They often don’t have the energy or the muscle strength, so they just stop breathing instead,” she says.

Mark Dworkin, MD, MPH, TM, the state epidemiologist and team leader for the Rapid Response Team at the Illinois Department of Public Health, is active in outbreak investigation. He wrote a compelling argument for maintaining a high index of suspicion when physicians see adolescent and adult patients who have a cough that has lasted more than two weeks.4

It has been estimated that more than one million cases of pertussis occur in the United States each year; that number has continued to grow for 20 years. From 1990 to 2001, the incidence of pertussis in adults increased by 400%. But many physicians believe that pertussis is only a pediatric illness. A survey of internists in Washington state showed that only 38% of respondents knew about the risk of vaccine fatigue, and just 36% knew that the nasopharyngeal swab is the preferred method for sample collection. Public health professionals were also concerned with the finding that too many pediatricians and nonpediatricians (43% and 41%, respectively) were not able to define a reportable case.

The first challenge that faces internists, writes Dr. Dworkin, is recognizing pertussis, which in some cases presents with mild symptoms; some adults won’t even have a cough.4 But at the other end of the disease spectrum, symptoms may be as brutal as bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage or rib fracture due to convulsive coughing. In any case, what goes unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated becomes a particularly serious risk for vulnerable infants. Once pertussis is identified, positive results on polymerase chain reaction or culture can help convince skeptical colleagues who may still believe pertussis is exclusively a childhood disease—and a vintage one at that.

“What we in pediatrics champion … is for [these immunizations] to help the young child; the less disease we have out there, the better off we’re going to eventually be,” says Dr. Stucky, who projects that, within just a few years, Tdap vaccinations for adolescents and adults up to age 64 might lead to a reduction of infection in the three-month-old group.6

Measles and Mumps

From January 1 to October 7, 2006, 45 states and the District of Columbia reported 5,783 confirmed or probable mumps cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (See Figures 2 and 3, above.)8 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) announced that continuing data from surveillance reports meant that healthcare workers should remain alert to suspected cases, conduct appropriate laboratory testing, and use every opportunity to ensure adequate immunity, particularly among populations at high risk.7

In contrast to the circumstances with pertussis, with mumps “there have been pockets of people who have either chosen not to immunize their child[ren], or their child[ren] get exposed to it somehow,” says Dr. Stucky, “and although they might be immunized, they might not have had a good response.” In an environment such as a school, “where one child can cough on a few and then cough on a few [more],” there is an environment where the infection can spread rampantly.

With mumps and measles, these could be called true outbreaks, such as the classic example that occurred in Kansas 18 years ago or the epidemic that disseminated from a college campus in Iowa in the spring of 2006, which originated from only two airline passengers on nine different flights within one week.8

College dorms and cafeterias can be treacherous breeding grounds for pathogens, and this generation of college students is susceptible for a few reasons. For one, in the late 1980s, when they were infants, the vaccine schedule was changed; the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine was upgraded from one dose to two—and not all children received the two doses.

The unimmunized who are exposed to measles and mumps remain at highest risk for spreading the disease. Although in 2005, 76%-79% of children aged 19-35 months received the entire recommended series of shots against whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenza type B, that still means that 21%-24% of the children—or potentially one out of five kids—did not.9

Other factors causing low levels of immunization include parents’ Internet-fueled fears of links to autism; immigrants crossing U.S. borders from Mexico or other countries where immunization is not standardized; religious and philosophical reasons; and international travel.10

“When young adults travel internationally [to places] where they are exposed to young children and adults who have never been immunized,” that’s a big risk, says Dr. Stucky. “All it would take is one [infected] student coming into a dorm and passing it around [to others with lapsed coverage or no immunization for the disease].” And while providers may think of travelers being exposed to diseases such as malaria and typhoid fever in developing countries, “in reality, a lot of the common things we’re immunizing for in our country are not immunized for in other countries, and those can be brought back.”

Rickets

The incidence of rickets is increasing, especially in black and Hispanic children and particularly in the north.11,12 Epidemiologists trace the rise to an increase in breast-feeding (good for immunity, but breast milk lacks substantial vitamin D), overuse of sunscreen or lack of exposure to sunlight, and changes in physician recommendations for vitamin supplementation. The effects of rickets alone can be profound, but other long-term consequences of vitamin D deficiency may include type I diabetes, cancer (especially of the prostate), and osteoporosis.12

In the past few decades, physicians have been less likely to recommend vitamin D supplementation for babies, and an interesting study by Davenport and colleagues correlates the year of medical school completion to that decline as well as substantial variability as to the age at which supplement use is begun.12 (See Figures 4a and 4b, left.)

“Most of the cases I have run into have been in [recent] African immigrants, where the mothers stay covered and they are vitamin D deficient,” says Dr. Holmes. “It’s wonderful that they culturally breast-feed, but they come to the U.S., and they’re pretty afraid to go outside in a new society.”

Varicella (Chicken Pox)

Varicella was removed from the CDC’s national notifiable disease list in 1981, but in 1995 a varicella vaccine was recommended for routine childhood vaccination.13 Before the licensure of that vaccine, varicella was a universal childhood disease in the U.S., causing 4 million cases, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths every year.14 In 2002, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists recommended that varicella be included in the National Notifiable Surveillance System by 2003 and that case-based surveillance in all states be established by 2005.13 CDC’s ACIP recommended in 2006 that a routine second dose of varicella vaccine be given to children between the ages of four and six years old.

Contracting chicken pox as an adult is a much more morbid occurrence than catching it as a child. Although varicella is not life threatening (as are diphtheria, tetanus, and measles) or sterility-causing (as is mumps), when the vaccine was approved, some pediatricians, including Dr. Stucky, became concerned that “now we’re creating a population that has never seen the wild-type varicella virus, and what does that mean? Were we just delaying something into an age category where people will get sicker?” Recognizing varicella, therefore, is critical even for hospitalists who treat adults.

Conclusion

“I’ve seen mumps, measles, varicella, pertussis,” says Dr. Stucky, “but our adult [hospitalist] partners hadn’t.” She encourages her colleagues who treat adult populations “to read and be diligent. These diseases can exist in adults, or even in children who were once vaccinated, and all hospitalists need to know “what to do, how to treat them, and [that] the consequences in adults are hands down worse than in children.”

Dr. Stucky believes hospitalists who treat adults would do well to consult physicians who practiced in the 1950s because they understand the history as well as clinical signs and symptoms of these diseases; she says, “For the hospitalist who treats adults, these are the equivalent of emerging infectious diseases.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Carmichael M. 'Vintage' bugs return. Newsweek. May 1, 2006:Vol. 147, p. 38. Available at: www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12440796/site/newsweek/. Accessed on November 29, 2006.

- Herwaldt LA. Pertussis in adults. What physicians need to know. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1510-1512.

- Schafer S, Gillette H, Hedberg K, et al. A community-wide pertussis outbreak: an argument for universal booster vaccination. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1317-1321.

- Dworkin MS. Adults are whooping, but are internists listening? Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 17;142(10):832-835. Available at: www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/142/10/832.pdf. Accessed on November 19, 2006.

- Gregory DS. Pertussis: a disease affecting all ages. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1;74(3):420-426.

- Finger R, Shoemaker J. Preventing pertussis in infants by vaccinating adults. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1;74(3):382.

- Broder KR, Cortese MM, Iskander JK, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-34.

- MMWR. Brief report: update: mumps activity—United States, January 1-October 7, 2006. MMWR. 2006 Oct 27;55(42):1152-1153.

- National Briefing: Science and health: race gap closes in vaccinations, U.S. says. New York Times. September 15, 2006.

- Calandrillo SP. Vanishing vaccinations: why are so many Americans opting out of vaccinating their children? Univ Mich J Law Reform. 2004 Winter;37(2):353-440.

- Kreiter SR, Schwartz RP, Kirkman HN Jr, et al. Nutritional rickets in African American breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 2000 Aug;137(2):153-157.

- Davenport ML, Uckun A, Calikoglu AS. Pediatrician patterns of prescribing vitamin supplementation for infants: do they contribute to rickets? Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(1 Pt 1):179-180.

- MMWR. Varicella surveillance practices—United States, 2004. MMWR. 2006 Oct 19;55:1126-1129.

- Seward JF, Watson BM, Peterson CL, et al. Varicella disease after introduction of varicella vaccine in the United States, 1995-2000. JAMA. 2002 Feb 6;287(5):606-611.

We thought they were gone, but they’ve returned: diseases once considered “vintage bugs” that were common in as late as the mid-20th century. In the past these diseases killed one in three people younger than 20 who had survived an infancy during which many of their contemporaries died.1

“When you think about disease states, you think about some that are gone from the world,” says Erin Stucky, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the University of California, San Diego, “but there are very few truly gone from the world.”

Some of the major infectious diseases that hospitalists may [still] see are pertussis (whooping cough), measles, and mumps, but scarlet fever and varicella (chicken pox) also endure—not to mention those occurrences of polio around the country that epidemiologists and infectious diseases specialists are monitoring closely. Rickets, a vitamin-D-deficiency-related disease also thought to be a relic of the 18th century, is showing up in certain patient populations—and not exclusively in infants and children.

This is a crossover clinical issue, our pediatric hospitalists say, and thus one to which their hospitalist partners who treat adult patients must also remain alert.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

Despite vaccination protocols, pediatric hospitalists continue to see whooping cough in young infants. (See Figure 1, p. 39.) Even with treatment, the damage can be severe, and the length of stay (LOS) is prolonged compared with those of most other patients with complex illnesses. “Vaccine fatigue” means that immunization lasts only until adolescence or early adulthood, at which time they need appropriate boosters. If the patient hasn’t receive boosters, the initial immunization loses its effectiveness; unprotected, they can be infected with the disease, though sometimes not badly enough for them to seek care. When they do, the diagnosis is often community-acquired mild pneumonia or a more traditional bronchitis. Either by accident or because the physician has given it thought, those illnesses are treated with a macrolide drug, which is also—coincidentally and serendipitously—the drug of choice for pertussis. But many remain carriers because they are not accurately diagnosed or never seek care.

“There is a huge reservoir of people carrying pertussis, particularly [in] the adolescent and adult population[s],” says Alison Holmes, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Concord Hospital, N.H. “And the babies who get really sick from it are the under two- to three-month group who have not yet been immunized or have just been immunized. Because it is so rampant in the adolescent and adult community, those children can still get sick.”

“Unfortunately,” says Dr. Stucky, “what’s happening is that if physicians are not thinking pertussis, they don’t talk about pertussis to that adult patient who … is either around children or has children in the home. So they don’t know to tell that person to watch for these same signs and symptoms in that young infant, who then could have a much more severe outcome from getting [the infection].”

As with most patients who contract illnesses, these patients may never have heard of the disease and unless educated may not understand the implications of the diagnosis. They might realize their disease could spread to family members, “but most people don’t absorb that information and use that information thoughtfully,” says Dr. Stucky. The onus is, therefore, on the physician to warn adult patients specifically about the serious danger that exists for infants in the two- to three-month-old group, who may not have been vaccinated or whose single-vaccination immunity is not adequate protection against the disease.

While the numbers in babies appear to be what they have always been, the incidence has grown in the teen years and even later into adulthood. This is more likely the result of increased testing for pertussis, as opposed to being only due to a true resurgence. Data from studies of adults with prolonged cough revealed that 20% to 25% have serologic evidence of recent pertussis infection.2 Adults are the major reservoir of infection, and infection spreads quickly in a population in a closed environment where droplets spread easily person to person.5

For both teens and adults, testing and immunization with the newly recommended DTaP (diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis)—as opposed to the more limited Td—can help upgrade immunity. Although a patient can recover from pertussis on his or her own within one to two weeks following treatment, the intent of treatment is primarily to limit the spread of disease to others.4-7

The problem when adults get pertussis, says Dr. Holmes, who is also an assistant professor of community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H., “is that they often don’t show up complaining about this horrible paroxysmal coughing until they’re about three or four weeks into the illness, and it hasn’t gone away. You go for hours and hours feeling completely fine and wonderful, and why would you bother going to the doctor?”

Babies are most at risk, however. “They often don’t have the energy or the muscle strength, so they just stop breathing instead,” she says.

Mark Dworkin, MD, MPH, TM, the state epidemiologist and team leader for the Rapid Response Team at the Illinois Department of Public Health, is active in outbreak investigation. He wrote a compelling argument for maintaining a high index of suspicion when physicians see adolescent and adult patients who have a cough that has lasted more than two weeks.4

It has been estimated that more than one million cases of pertussis occur in the United States each year; that number has continued to grow for 20 years. From 1990 to 2001, the incidence of pertussis in adults increased by 400%. But many physicians believe that pertussis is only a pediatric illness. A survey of internists in Washington state showed that only 38% of respondents knew about the risk of vaccine fatigue, and just 36% knew that the nasopharyngeal swab is the preferred method for sample collection. Public health professionals were also concerned with the finding that too many pediatricians and nonpediatricians (43% and 41%, respectively) were not able to define a reportable case.

The first challenge that faces internists, writes Dr. Dworkin, is recognizing pertussis, which in some cases presents with mild symptoms; some adults won’t even have a cough.4 But at the other end of the disease spectrum, symptoms may be as brutal as bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage or rib fracture due to convulsive coughing. In any case, what goes unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated becomes a particularly serious risk for vulnerable infants. Once pertussis is identified, positive results on polymerase chain reaction or culture can help convince skeptical colleagues who may still believe pertussis is exclusively a childhood disease—and a vintage one at that.

“What we in pediatrics champion … is for [these immunizations] to help the young child; the less disease we have out there, the better off we’re going to eventually be,” says Dr. Stucky, who projects that, within just a few years, Tdap vaccinations for adolescents and adults up to age 64 might lead to a reduction of infection in the three-month-old group.6

Measles and Mumps

From January 1 to October 7, 2006, 45 states and the District of Columbia reported 5,783 confirmed or probable mumps cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (See Figures 2 and 3, above.)8 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) announced that continuing data from surveillance reports meant that healthcare workers should remain alert to suspected cases, conduct appropriate laboratory testing, and use every opportunity to ensure adequate immunity, particularly among populations at high risk.7

In contrast to the circumstances with pertussis, with mumps “there have been pockets of people who have either chosen not to immunize their child[ren], or their child[ren] get exposed to it somehow,” says Dr. Stucky, “and although they might be immunized, they might not have had a good response.” In an environment such as a school, “where one child can cough on a few and then cough on a few [more],” there is an environment where the infection can spread rampantly.

With mumps and measles, these could be called true outbreaks, such as the classic example that occurred in Kansas 18 years ago or the epidemic that disseminated from a college campus in Iowa in the spring of 2006, which originated from only two airline passengers on nine different flights within one week.8

College dorms and cafeterias can be treacherous breeding grounds for pathogens, and this generation of college students is susceptible for a few reasons. For one, in the late 1980s, when they were infants, the vaccine schedule was changed; the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine was upgraded from one dose to two—and not all children received the two doses.

The unimmunized who are exposed to measles and mumps remain at highest risk for spreading the disease. Although in 2005, 76%-79% of children aged 19-35 months received the entire recommended series of shots against whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenza type B, that still means that 21%-24% of the children—or potentially one out of five kids—did not.9

Other factors causing low levels of immunization include parents’ Internet-fueled fears of links to autism; immigrants crossing U.S. borders from Mexico or other countries where immunization is not standardized; religious and philosophical reasons; and international travel.10

“When young adults travel internationally [to places] where they are exposed to young children and adults who have never been immunized,” that’s a big risk, says Dr. Stucky. “All it would take is one [infected] student coming into a dorm and passing it around [to others with lapsed coverage or no immunization for the disease].” And while providers may think of travelers being exposed to diseases such as malaria and typhoid fever in developing countries, “in reality, a lot of the common things we’re immunizing for in our country are not immunized for in other countries, and those can be brought back.”

Rickets

The incidence of rickets is increasing, especially in black and Hispanic children and particularly in the north.11,12 Epidemiologists trace the rise to an increase in breast-feeding (good for immunity, but breast milk lacks substantial vitamin D), overuse of sunscreen or lack of exposure to sunlight, and changes in physician recommendations for vitamin supplementation. The effects of rickets alone can be profound, but other long-term consequences of vitamin D deficiency may include type I diabetes, cancer (especially of the prostate), and osteoporosis.12

In the past few decades, physicians have been less likely to recommend vitamin D supplementation for babies, and an interesting study by Davenport and colleagues correlates the year of medical school completion to that decline as well as substantial variability as to the age at which supplement use is begun.12 (See Figures 4a and 4b, left.)

“Most of the cases I have run into have been in [recent] African immigrants, where the mothers stay covered and they are vitamin D deficient,” says Dr. Holmes. “It’s wonderful that they culturally breast-feed, but they come to the U.S., and they’re pretty afraid to go outside in a new society.”

Varicella (Chicken Pox)

Varicella was removed from the CDC’s national notifiable disease list in 1981, but in 1995 a varicella vaccine was recommended for routine childhood vaccination.13 Before the licensure of that vaccine, varicella was a universal childhood disease in the U.S., causing 4 million cases, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths every year.14 In 2002, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists recommended that varicella be included in the National Notifiable Surveillance System by 2003 and that case-based surveillance in all states be established by 2005.13 CDC’s ACIP recommended in 2006 that a routine second dose of varicella vaccine be given to children between the ages of four and six years old.

Contracting chicken pox as an adult is a much more morbid occurrence than catching it as a child. Although varicella is not life threatening (as are diphtheria, tetanus, and measles) or sterility-causing (as is mumps), when the vaccine was approved, some pediatricians, including Dr. Stucky, became concerned that “now we’re creating a population that has never seen the wild-type varicella virus, and what does that mean? Were we just delaying something into an age category where people will get sicker?” Recognizing varicella, therefore, is critical even for hospitalists who treat adults.

Conclusion

“I’ve seen mumps, measles, varicella, pertussis,” says Dr. Stucky, “but our adult [hospitalist] partners hadn’t.” She encourages her colleagues who treat adult populations “to read and be diligent. These diseases can exist in adults, or even in children who were once vaccinated, and all hospitalists need to know “what to do, how to treat them, and [that] the consequences in adults are hands down worse than in children.”

Dr. Stucky believes hospitalists who treat adults would do well to consult physicians who practiced in the 1950s because they understand the history as well as clinical signs and symptoms of these diseases; she says, “For the hospitalist who treats adults, these are the equivalent of emerging infectious diseases.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Carmichael M. 'Vintage' bugs return. Newsweek. May 1, 2006:Vol. 147, p. 38. Available at: www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12440796/site/newsweek/. Accessed on November 29, 2006.

- Herwaldt LA. Pertussis in adults. What physicians need to know. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1510-1512.

- Schafer S, Gillette H, Hedberg K, et al. A community-wide pertussis outbreak: an argument for universal booster vaccination. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1317-1321.

- Dworkin MS. Adults are whooping, but are internists listening? Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 17;142(10):832-835. Available at: www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/142/10/832.pdf. Accessed on November 19, 2006.

- Gregory DS. Pertussis: a disease affecting all ages. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1;74(3):420-426.

- Finger R, Shoemaker J. Preventing pertussis in infants by vaccinating adults. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1;74(3):382.

- Broder KR, Cortese MM, Iskander JK, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-34.

- MMWR. Brief report: update: mumps activity—United States, January 1-October 7, 2006. MMWR. 2006 Oct 27;55(42):1152-1153.

- National Briefing: Science and health: race gap closes in vaccinations, U.S. says. New York Times. September 15, 2006.

- Calandrillo SP. Vanishing vaccinations: why are so many Americans opting out of vaccinating their children? Univ Mich J Law Reform. 2004 Winter;37(2):353-440.

- Kreiter SR, Schwartz RP, Kirkman HN Jr, et al. Nutritional rickets in African American breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 2000 Aug;137(2):153-157.

- Davenport ML, Uckun A, Calikoglu AS. Pediatrician patterns of prescribing vitamin supplementation for infants: do they contribute to rickets? Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(1 Pt 1):179-180.

- MMWR. Varicella surveillance practices—United States, 2004. MMWR. 2006 Oct 19;55:1126-1129.

- Seward JF, Watson BM, Peterson CL, et al. Varicella disease after introduction of varicella vaccine in the United States, 1995-2000. JAMA. 2002 Feb 6;287(5):606-611.