User login

A 26-year-old G2P1001 at 35 weeks, 2 days of gestation presents with leakage of clear fluid for the past two hours. There is obvious pooling in the vaginal vault, and rupture of membranes is confirmed with appropriate testing. Her cervix is closed, she is not in labor, and tests of fetal well-being are reassuring. She had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery with her first child. How should you manage this situation?

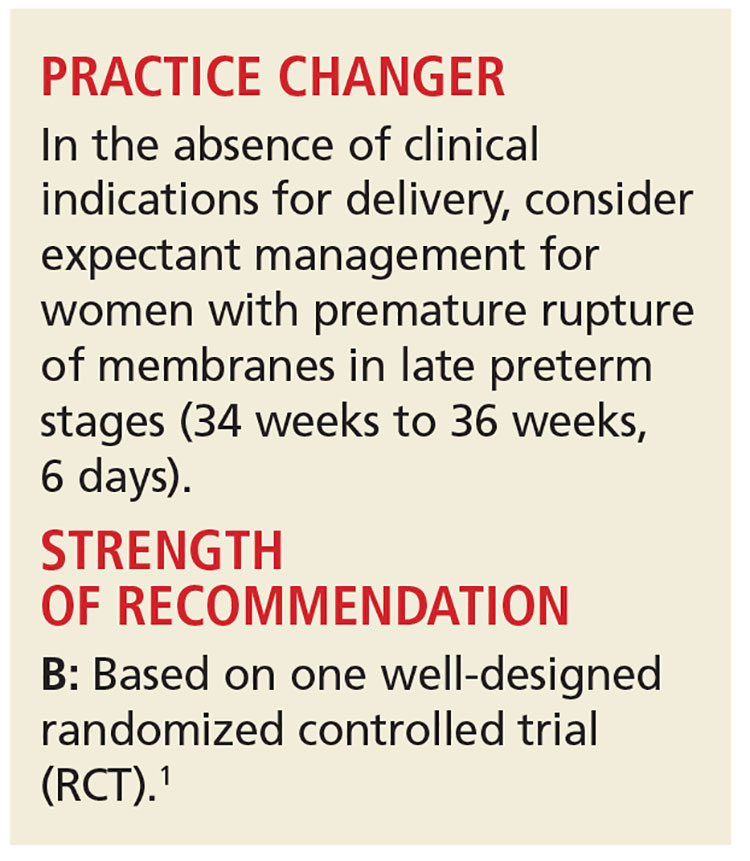

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM)—when rupture of membranes occurs before 37 weeks’ gestation—affects about 3% of all pregnancies in the United States and is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality.2,3 PPROM management remains controversial, especially during the late preterm stage (ie, from 34 weeks to 36 weeks, 6 days). Non-reassuring fetal status, clinical chorioamnionitis, cord prolapse, and significant placental abruption are clear indications for delivery.

In the absence of these factors, delivery versus expectant management is determined by gestational age. Between 23 and 34 weeks’ gestation, when the fetus is at or close to viability, expectant management is recommended if there are no signs of infection or maternal or fetal compromise. This is because of the significant morbidity and mortality risk associated with births before 34 weeks’ gestation.4

Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends delivery for all women with rupture of membranes after 34 weeks’ gestation, while acknowledging that this recommendation is based on “limited and inconsistent scientific evidence.”5 The recommendation for delivery after 34 weeks is predicated on the belief that disability-free survival is high in late preterm infants. However, there is a growing body of evidence that shows negative short- and long-term effects for these children, including medical concerns, academic difficulties, and more frequent hospital admissions in early childhood.6,7

STUDY SUMMARY

Higher birth weights, fewer C-sections, and no increased sepsis

The Preterm Pre-labour Rupture of the Membranes close to Term (PPROMT) trial was a multicenter RCT that included 1,839 women with singleton pregnancies and confirmed rupture of membranes between 34 weeks and 36 weeks, 6 days’ gestation.1 Participants were randomized to either expectant management or immediate delivery by induction. Patients and care providers were not masked to treatment allocation, but those determining the primary outcome were masked to group allocation.

One woman in each group was lost to follow-up, and two additional women withdrew from the immediate birth group. Women already in active labor or with clinical indications for delivery (ie, chorioamnionitis, abruption, cord prolapse, fetal distress) were excluded. The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar.

Women in the induction group had delivery scheduled as soon as possible after randomization. Women in the expectant management group were allowed to go into spontaneous labor and were only induced if they reached term or the clinician identified other indications for immediate delivery.

The primary outcome was probable or confirmed neonatal sepsis. Secondary infant outcomes included a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality indicator (ie, sepsis, mechanical ventilation ≥ 24 h, stillbirth, or neonatal death), respiratory distress syndrome, any mechanical ventilation, low birth weight, and duration of stay in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or special care nursery. Secondary maternal outcomes included antepartum or intrapartum hemorrhage, intrapartum fever, mode of delivery, duration of hospital stay, and development of chorioamnionitis in the expectant management group.

The primary outcome of neonatal sepsis occurred in 2% of the neonates assigned to immediate delivery and 3% of neonates assigned to expectant management (relative risk [RR], 0.8). There was also no statistically significant difference in composite neonatal morbidity and mortality (RR, 1.2). However, infants born in the immediate delivery group had significantly lower birth weights (2,574.7 g vs 2,673.2 g; absolute difference, –125 g), a higher incidence of respiratory distress (RR, 1.6; number needed to treat [NNT], 32), and spent more time in the NICU/special care nursery (four days vs two days).

Compared to immediate delivery, expectant management was associated with a higher likelihood of antepartum or intrapartum hemorrhage (RR, 0.6; number needed to harm [NNH], 50) and intrapartum fever (RR, 0.4; NNH, 100). Of the women assigned to immediate delivery, 26% had a cesarean section, compared to 19% of the expectant management group (RR, 1.4; NNT, 14). Six percent of the women assigned to the expectant management group developed clinically significant chorioamnionitis requiring delivery. All other secondary maternal and neonatal outcomes were equivalent, with no significant differences between the two groups.

WHAT’S NEW?

Largest study to show no increased sepsis with expectant management

Two prior RCTs (involving 736 women) evaluated expectant management versus induction in the late preterm stage of pregnancy. No increased risk for neonatal sepsis with expectant management was found in either study.8,9

However, those studies did not have sufficient power to show a statistically significant change in any of the outcomes. The PPROMT study is the largest to indicate that immediate birth increases infant risk for respiratory distress and duration of NICU/special care stay and increases the mother’s risk for cesarean section. It also showed that risk for neonatal sepsis was not higher in the expectant management group.

CAVEATS

Singleton pregnancies only

Delivery of the infants in the expectant management group was not by specified protocol; each birth was managed according to the policies of the local center and clinician judgment. This created variation in fetal and maternal monitoring. The majority of women in both groups (92% to 93%) received intrapartum antibiotics. Expectant management should include careful monitoring for infection and hemorrhage. If one of these occurs, immediate delivery may be necessary.

The study participants all had singleton pregnancies; this recommendation cannot be extended to non-singleton pregnancies. However, a prior cesarean section was not an exclusion criterion for the study, and these recommendations would be valid for that group of women, as well.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Going against the tide of ACOG

The most recent ACOG guidelines (updated October 2016) recommend induction of labor for women with ruptured membranes in the late preterm stages.5 This may present a challenge to widespread acceptance of expectant management for PPROM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(11):820-822.

1. Morris JM, Roberts CL, Bowen JR, et al; PPROMT Collaboration. Immediate delivery compared with expectant management after preterm pre-labour rupture of the membranes close to term (PPROMT trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387: 444-452.

2. Waters TP, Mercer B. Preterm PROM: prediction, prevention, principles. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:307-312.

3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1-72.

4. Buchanan SL, Crowther CA, Levett KM, et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management for women with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes prior to 37 weeks’ gestation for improving pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3: CD004735.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No 172: Premature rupture of membranes [interim update]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:934-936.

6. McGowan JE, Alderdice FA, Holmes VA, et al. Early childhood development of late-preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1111-1124.

7. Teune MJ, Bakhuizen S, Gyamfi Bannerman C, et al. A systematic review of severe morbidity in infants born late preterm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:374.

8. van der Ham DP, Vijgen SM, Nijhuis JG, et al; PPROMEXIL trial group. Induction of labor versus expectant management in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes between 34 and 37 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001208.

9. van der Ham DP, van der Heyden JL, Opmeer BC, et al. Management of late-preterm premature rupture of membranes: the PPROMEXIL-2 trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 207:276.

A 26-year-old G2P1001 at 35 weeks, 2 days of gestation presents with leakage of clear fluid for the past two hours. There is obvious pooling in the vaginal vault, and rupture of membranes is confirmed with appropriate testing. Her cervix is closed, she is not in labor, and tests of fetal well-being are reassuring. She had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery with her first child. How should you manage this situation?

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM)—when rupture of membranes occurs before 37 weeks’ gestation—affects about 3% of all pregnancies in the United States and is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality.2,3 PPROM management remains controversial, especially during the late preterm stage (ie, from 34 weeks to 36 weeks, 6 days). Non-reassuring fetal status, clinical chorioamnionitis, cord prolapse, and significant placental abruption are clear indications for delivery.

In the absence of these factors, delivery versus expectant management is determined by gestational age. Between 23 and 34 weeks’ gestation, when the fetus is at or close to viability, expectant management is recommended if there are no signs of infection or maternal or fetal compromise. This is because of the significant morbidity and mortality risk associated with births before 34 weeks’ gestation.4

Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends delivery for all women with rupture of membranes after 34 weeks’ gestation, while acknowledging that this recommendation is based on “limited and inconsistent scientific evidence.”5 The recommendation for delivery after 34 weeks is predicated on the belief that disability-free survival is high in late preterm infants. However, there is a growing body of evidence that shows negative short- and long-term effects for these children, including medical concerns, academic difficulties, and more frequent hospital admissions in early childhood.6,7

STUDY SUMMARY

Higher birth weights, fewer C-sections, and no increased sepsis

The Preterm Pre-labour Rupture of the Membranes close to Term (PPROMT) trial was a multicenter RCT that included 1,839 women with singleton pregnancies and confirmed rupture of membranes between 34 weeks and 36 weeks, 6 days’ gestation.1 Participants were randomized to either expectant management or immediate delivery by induction. Patients and care providers were not masked to treatment allocation, but those determining the primary outcome were masked to group allocation.

One woman in each group was lost to follow-up, and two additional women withdrew from the immediate birth group. Women already in active labor or with clinical indications for delivery (ie, chorioamnionitis, abruption, cord prolapse, fetal distress) were excluded. The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar.

Women in the induction group had delivery scheduled as soon as possible after randomization. Women in the expectant management group were allowed to go into spontaneous labor and were only induced if they reached term or the clinician identified other indications for immediate delivery.

The primary outcome was probable or confirmed neonatal sepsis. Secondary infant outcomes included a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality indicator (ie, sepsis, mechanical ventilation ≥ 24 h, stillbirth, or neonatal death), respiratory distress syndrome, any mechanical ventilation, low birth weight, and duration of stay in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or special care nursery. Secondary maternal outcomes included antepartum or intrapartum hemorrhage, intrapartum fever, mode of delivery, duration of hospital stay, and development of chorioamnionitis in the expectant management group.

The primary outcome of neonatal sepsis occurred in 2% of the neonates assigned to immediate delivery and 3% of neonates assigned to expectant management (relative risk [RR], 0.8). There was also no statistically significant difference in composite neonatal morbidity and mortality (RR, 1.2). However, infants born in the immediate delivery group had significantly lower birth weights (2,574.7 g vs 2,673.2 g; absolute difference, –125 g), a higher incidence of respiratory distress (RR, 1.6; number needed to treat [NNT], 32), and spent more time in the NICU/special care nursery (four days vs two days).

Compared to immediate delivery, expectant management was associated with a higher likelihood of antepartum or intrapartum hemorrhage (RR, 0.6; number needed to harm [NNH], 50) and intrapartum fever (RR, 0.4; NNH, 100). Of the women assigned to immediate delivery, 26% had a cesarean section, compared to 19% of the expectant management group (RR, 1.4; NNT, 14). Six percent of the women assigned to the expectant management group developed clinically significant chorioamnionitis requiring delivery. All other secondary maternal and neonatal outcomes were equivalent, with no significant differences between the two groups.

WHAT’S NEW?

Largest study to show no increased sepsis with expectant management

Two prior RCTs (involving 736 women) evaluated expectant management versus induction in the late preterm stage of pregnancy. No increased risk for neonatal sepsis with expectant management was found in either study.8,9

However, those studies did not have sufficient power to show a statistically significant change in any of the outcomes. The PPROMT study is the largest to indicate that immediate birth increases infant risk for respiratory distress and duration of NICU/special care stay and increases the mother’s risk for cesarean section. It also showed that risk for neonatal sepsis was not higher in the expectant management group.

CAVEATS

Singleton pregnancies only

Delivery of the infants in the expectant management group was not by specified protocol; each birth was managed according to the policies of the local center and clinician judgment. This created variation in fetal and maternal monitoring. The majority of women in both groups (92% to 93%) received intrapartum antibiotics. Expectant management should include careful monitoring for infection and hemorrhage. If one of these occurs, immediate delivery may be necessary.

The study participants all had singleton pregnancies; this recommendation cannot be extended to non-singleton pregnancies. However, a prior cesarean section was not an exclusion criterion for the study, and these recommendations would be valid for that group of women, as well.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Going against the tide of ACOG

The most recent ACOG guidelines (updated October 2016) recommend induction of labor for women with ruptured membranes in the late preterm stages.5 This may present a challenge to widespread acceptance of expectant management for PPROM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(11):820-822.

A 26-year-old G2P1001 at 35 weeks, 2 days of gestation presents with leakage of clear fluid for the past two hours. There is obvious pooling in the vaginal vault, and rupture of membranes is confirmed with appropriate testing. Her cervix is closed, she is not in labor, and tests of fetal well-being are reassuring. She had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery with her first child. How should you manage this situation?

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM)—when rupture of membranes occurs before 37 weeks’ gestation—affects about 3% of all pregnancies in the United States and is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality.2,3 PPROM management remains controversial, especially during the late preterm stage (ie, from 34 weeks to 36 weeks, 6 days). Non-reassuring fetal status, clinical chorioamnionitis, cord prolapse, and significant placental abruption are clear indications for delivery.

In the absence of these factors, delivery versus expectant management is determined by gestational age. Between 23 and 34 weeks’ gestation, when the fetus is at or close to viability, expectant management is recommended if there are no signs of infection or maternal or fetal compromise. This is because of the significant morbidity and mortality risk associated with births before 34 weeks’ gestation.4

Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends delivery for all women with rupture of membranes after 34 weeks’ gestation, while acknowledging that this recommendation is based on “limited and inconsistent scientific evidence.”5 The recommendation for delivery after 34 weeks is predicated on the belief that disability-free survival is high in late preterm infants. However, there is a growing body of evidence that shows negative short- and long-term effects for these children, including medical concerns, academic difficulties, and more frequent hospital admissions in early childhood.6,7

STUDY SUMMARY

Higher birth weights, fewer C-sections, and no increased sepsis

The Preterm Pre-labour Rupture of the Membranes close to Term (PPROMT) trial was a multicenter RCT that included 1,839 women with singleton pregnancies and confirmed rupture of membranes between 34 weeks and 36 weeks, 6 days’ gestation.1 Participants were randomized to either expectant management or immediate delivery by induction. Patients and care providers were not masked to treatment allocation, but those determining the primary outcome were masked to group allocation.

One woman in each group was lost to follow-up, and two additional women withdrew from the immediate birth group. Women already in active labor or with clinical indications for delivery (ie, chorioamnionitis, abruption, cord prolapse, fetal distress) were excluded. The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar.

Women in the induction group had delivery scheduled as soon as possible after randomization. Women in the expectant management group were allowed to go into spontaneous labor and were only induced if they reached term or the clinician identified other indications for immediate delivery.

The primary outcome was probable or confirmed neonatal sepsis. Secondary infant outcomes included a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality indicator (ie, sepsis, mechanical ventilation ≥ 24 h, stillbirth, or neonatal death), respiratory distress syndrome, any mechanical ventilation, low birth weight, and duration of stay in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or special care nursery. Secondary maternal outcomes included antepartum or intrapartum hemorrhage, intrapartum fever, mode of delivery, duration of hospital stay, and development of chorioamnionitis in the expectant management group.

The primary outcome of neonatal sepsis occurred in 2% of the neonates assigned to immediate delivery and 3% of neonates assigned to expectant management (relative risk [RR], 0.8). There was also no statistically significant difference in composite neonatal morbidity and mortality (RR, 1.2). However, infants born in the immediate delivery group had significantly lower birth weights (2,574.7 g vs 2,673.2 g; absolute difference, –125 g), a higher incidence of respiratory distress (RR, 1.6; number needed to treat [NNT], 32), and spent more time in the NICU/special care nursery (four days vs two days).

Compared to immediate delivery, expectant management was associated with a higher likelihood of antepartum or intrapartum hemorrhage (RR, 0.6; number needed to harm [NNH], 50) and intrapartum fever (RR, 0.4; NNH, 100). Of the women assigned to immediate delivery, 26% had a cesarean section, compared to 19% of the expectant management group (RR, 1.4; NNT, 14). Six percent of the women assigned to the expectant management group developed clinically significant chorioamnionitis requiring delivery. All other secondary maternal and neonatal outcomes were equivalent, with no significant differences between the two groups.

WHAT’S NEW?

Largest study to show no increased sepsis with expectant management

Two prior RCTs (involving 736 women) evaluated expectant management versus induction in the late preterm stage of pregnancy. No increased risk for neonatal sepsis with expectant management was found in either study.8,9

However, those studies did not have sufficient power to show a statistically significant change in any of the outcomes. The PPROMT study is the largest to indicate that immediate birth increases infant risk for respiratory distress and duration of NICU/special care stay and increases the mother’s risk for cesarean section. It also showed that risk for neonatal sepsis was not higher in the expectant management group.

CAVEATS

Singleton pregnancies only

Delivery of the infants in the expectant management group was not by specified protocol; each birth was managed according to the policies of the local center and clinician judgment. This created variation in fetal and maternal monitoring. The majority of women in both groups (92% to 93%) received intrapartum antibiotics. Expectant management should include careful monitoring for infection and hemorrhage. If one of these occurs, immediate delivery may be necessary.

The study participants all had singleton pregnancies; this recommendation cannot be extended to non-singleton pregnancies. However, a prior cesarean section was not an exclusion criterion for the study, and these recommendations would be valid for that group of women, as well.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Going against the tide of ACOG

The most recent ACOG guidelines (updated October 2016) recommend induction of labor for women with ruptured membranes in the late preterm stages.5 This may present a challenge to widespread acceptance of expectant management for PPROM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(11):820-822.

1. Morris JM, Roberts CL, Bowen JR, et al; PPROMT Collaboration. Immediate delivery compared with expectant management after preterm pre-labour rupture of the membranes close to term (PPROMT trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387: 444-452.

2. Waters TP, Mercer B. Preterm PROM: prediction, prevention, principles. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:307-312.

3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1-72.

4. Buchanan SL, Crowther CA, Levett KM, et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management for women with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes prior to 37 weeks’ gestation for improving pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3: CD004735.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No 172: Premature rupture of membranes [interim update]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:934-936.

6. McGowan JE, Alderdice FA, Holmes VA, et al. Early childhood development of late-preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1111-1124.

7. Teune MJ, Bakhuizen S, Gyamfi Bannerman C, et al. A systematic review of severe morbidity in infants born late preterm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:374.

8. van der Ham DP, Vijgen SM, Nijhuis JG, et al; PPROMEXIL trial group. Induction of labor versus expectant management in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes between 34 and 37 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001208.

9. van der Ham DP, van der Heyden JL, Opmeer BC, et al. Management of late-preterm premature rupture of membranes: the PPROMEXIL-2 trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 207:276.

1. Morris JM, Roberts CL, Bowen JR, et al; PPROMT Collaboration. Immediate delivery compared with expectant management after preterm pre-labour rupture of the membranes close to term (PPROMT trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387: 444-452.

2. Waters TP, Mercer B. Preterm PROM: prediction, prevention, principles. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:307-312.

3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1-72.

4. Buchanan SL, Crowther CA, Levett KM, et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management for women with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes prior to 37 weeks’ gestation for improving pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3: CD004735.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No 172: Premature rupture of membranes [interim update]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:934-936.

6. McGowan JE, Alderdice FA, Holmes VA, et al. Early childhood development of late-preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1111-1124.

7. Teune MJ, Bakhuizen S, Gyamfi Bannerman C, et al. A systematic review of severe morbidity in infants born late preterm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:374.

8. van der Ham DP, Vijgen SM, Nijhuis JG, et al; PPROMEXIL trial group. Induction of labor versus expectant management in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes between 34 and 37 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001208.

9. van der Ham DP, van der Heyden JL, Opmeer BC, et al. Management of late-preterm premature rupture of membranes: the PPROMEXIL-2 trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 207:276.