User login

This is the first of a two-part series examining medical errors. This article addresses thought processes hospitalists use that may lead to mistaken diagnoses. Part 2 will look at what healthcare corporations are doing to improve diagnoses and reduce errors.

When talking about tough diagnoses, academic hospitalist David Feinbloom, MD, recalls the story of a female patient seen by his hospitalist group whose diagnosis took some time to nail down.

This woman had been in and out of the hospital for several years with nonspecific abdominal pain and intermittent diarrhea. She had been seen by numerous doctors and tested extensively. Increasingly her doctors concluded that there was some psychiatric overlay—she was depressed or somatic.

“Patients like these are very common and often end up on the hospitalist service,” says Dr. Feinbloom, who works at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

But to Joseph Li, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel, this patient seemed normal. There was something about the symptoms she described that reminded him of a patient he had seen who had been diagnosed with a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Although this patient’s past MRI had been negative, Dr. Li remembered that if you don’t perform the right MRI protocol, you’ll miss something. He asked the team to obtain a panel looking for specific markers and to repeat the MRI with the correct protocol. It was accepted as fact that there was no pathology to explain her symptoms but that she had had every test. He requested another gastrointestinal (GI) consult.

“It seemed so far out there, and then everything he said was completely correct,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “She had Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.”

Clues from Sherlock

In his book How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, discusses Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, physician and creator of the brilliant detective Sherlock Holmes. When it comes to solving crimes, Holmes’ superior observation and logic, intellectual prowess, and pristine reasoning help him observe and interpret the most obscure and arcane clues. He is, in the end, a consummate diagnostician.

One of the first rules a great diagnostician must follow is to not get boxed into one way of thinking, says Dr. Groopman, the Dina and Raphael Recanati chair of medicine at the Harvard Medical School and chief of experimental medicine at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. That is one of the downsides of a too-easy attachment to using clinical practice guidelines, he says.

“Guidelines are valuable reference points, but in order to use a guideline effectively, you have to have the correct diagnosis,” he says. “Studies over decades with hospitalized patients show that the misdiagnosis rate is at least 15% and hasn’t changed.1 A great deal of effort needs to be put into improving our accuracy in making diagnoses.”

Compared with other kinds of medical errors, diagnostic errors have not gotten a great deal of attention. The hospital patient safety movement has been more focused on preventing medication errors, surgical errors, handoff communications, nosocomial infections, falls, and blood clots.2 There have been few studies pertaining exclusively to diagnostic errors—but the topic is gaining headway.3

Think about Thinking

Diagnostic errors are usually multifactorial in origin and typically involve system-related and individual factors. The systems-based piece includes environmental and organizational factors. Medical researchers conclude the majority of diagnostic errors arise from flaws in physician thinking, not technical mistakes.

Cognitive errors involve instances where knowledge, data gathering, data processing, or verification (such as by lab testing) are faulty. Improving diagnostics will require better accountability by institutions and individuals. To do the latter, experts say, physicians would do well to familiarize themselves with their diagnostic weaknesses.

Thinking about thinking is the science of cognitive psychology and addresses the cognitive aspects of clinical reasoning underlying diagnostic decision-making. It is an area of study in which few medical professionals are versed. “Except for a few of these guys who trained in psych or were voices in the wilderness that have been largely ignored,” most physicians are unaware of the cognitive psychology literature, Dr. Groopman says.

Common biases and errors in clinical reasoning are presented in Table 1 (right).4,5 These are largely individual mistakes for which physicians traditionally have been accountable.

Patterns and Heuristics

The following factors contribute to how shortcuts are used: the pressures of working in medicine, the degrees of uncertainty a physician may feel, and the fact that hospitalists rarely have all the information they need about a patient.

“That’s just the nature of medicine,” says Dr. Groopman. “These shortcuts are natural ways of thinking under those conditions. They succeed about 85% of the time; they fail up to 10-20% of the time. The first thing we need to educate ourselves about is that this is how our minds work as doctors.”

Dr. Groopman and those he interviewed for his book have a razor-sharp overview of clinical practice within hospitals throughout the U.S. and Canada, including academic centers, community centers, affluent areas, suburbs, inner cities, and Native American reservations. But except for Pat Croskerry, MD, PhD, in the department of emergency medicine at Dalhousie University’s Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center in Halifax, Nova Scotia, none of the experts he interviewed had rigorous training in cognitive science.

Although how to think is a priority in physicians’ training, how to think about one’s thinking is not.

“We are not given a vocabulary during medical training, or later through CME courses, in this emerging science—and yet this science involves how our mind works successfully and when we make mistakes,” Dr. Groopman says.

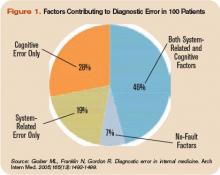

The data back this assertion. In a study of 100 cases of diagnostic error, 90 involved injury, including 33 deaths; 74% were attributed to errors in cognitive reasoning (see Figure 1, right).1 Failure to consider reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis was the most common cause. Other common causes included faulty context generation, misjudging the salience of findings, faulty perception, and errors connected with the use of heuristics. In this study, faulty or inadequate knowledge was uncommon.

Underlying contributions to error fell into three categories: “no fault,” system-related, and cognitive. Only seven cases reflected no-fault errors alone. In the remaining 93 cases, 548 errors were identified as system-related or cognitive factors (5.9 per case). System-related factors contributed to the diagnostic error in 65% of the cases and cognitive factors in 74%. The most common system-related factors involved problems with policies and procedures, inefficient processes, teamwork, and communication. The most common cognitive problems involved faulty synthesis.

Dr. Groopman believes it is important for physicians to be more introspective about the thinking patterns they employ and learn the traps to which they are susceptible. He also feels it is imperative to develop curricula at different stages of medical training so this new knowledge can be used to reduce error rates. Because the names for these traps can vary, the development of a universal and comprehensive taxonomy for classifying diagnostic errors is also needed.

“It’s impossible to be perfect; we’re never going to be 100%,” Dr. Groopman says. “But I deeply believe that it is quite feasible to think about your thinking and to assess how your mind came to a conclusion about a diagnosis and treatment plan.”

When phy-sicians think about errors in cognitive reasoning, they often focus on the “don’t-miss diagnoses” or the uncommon variant missed by recall or anchoring errors.

“When I reflect on the errors I have made, they mostly fall into the categories that Dr. Groopman describes in his book,” Dr. Feinbloom says. “Interestingly, the errors that I see most often stem from the fear of making an error of omission.”

It is paradoxical, but in order to ensure that no possible diagnosis is missed, doctors often feel the need to rule out all possible diagnoses.

“While it makes us feel that we are doing the best for our patients, this approach leads to an inordinate amount of unnecessary testing and potentially harmful interventions,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “Understanding how cognitive errors occur should allow us to be judicious in our approach, with the confidence to hold back when the diagnosis is clear, and push harder when we know that something does not fit.”

Emotional Dimension

Although many diagnostic errors are attributable to mistakes in thinking, emotions, and feelings—which may not be easy to detect or admit—also contribute to decision-making.

As hypothesized by noted neurologist and author Antonio Damasio in Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, some feelings—visceral signals he calls somatic markers—deter us from or attract us to certain images and decisions.6 Remaining cognizant of those feelings helps clarify how they may inform a medical decision—for good and bad.

The emotional dimension of decision-making cannot be disregarded, says Dr. Groopman. “We need to take our emotional temperature; there are patients we like more and patients we like less,” he says. “There are times when we are tremendously motivated to succeed with a very complicated and daunting patient in the hospital, and there are times when we retreat from that for whatever psychological reason. Sometimes it’s fear of failure, sometimes it’s stereotyping. Regardless, we need to have a level of self-awareness.”

The stressful atmosphere of hospital-based medicine contributes to a high level of anxiety. “Physicians use a telegraphic language full of sound bytes with each other that may contribute to the way heuristics are passed from one generation of doctors to the next,” Dr. Groopman says. “That language is enormously powerful in guiding our thinking and the kinds of shortcuts that we use.”

Pitfalls in Reasoning

Of all the bias errors in clinical reasoning, two of the most influential on physicians are anchoring and attribution. Bound-ed rationality—the failure to continue considering reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis is reached—is also a pitfall. The difference between the latter and anchoring is whether the clinician adjusts the diagnosis when new data emerge.

Anchoring errors may arise from seizing the first bits of data and allowing them to guide all future questioning. “It happens every day,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “The diagnosis kind of feels right. There is something about the speed with which it comes to mind, the familiarity with the diagnosis in question, [that] reinforces your confidence.”

Dr. Feinbloom teaches his young trainees to trust no one. “I mean that in a good-hearted way,” he says. “Never assume what you’re told is accurate. You have to review everything yourself, interview the patient again; skepticism is a powerful tool.”

With the woman who was ultimately diagnosed with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, Dr. Li’s skepticism paid off—and the hospitalist team benefited from deconstructing its clinical thinking to see where it went awry.

“If someone had gotten the gastrin level earlier,” says Dr. Feinbloom, “they would have caught it, but it was not on anyone’s radar. When imaging was negative, the team assumed it wasn’t a tumor.”

Lessons Learned

There are lots of lessons here, says Dr. Feinbloom. “You could spin it any one of five different ways with heuristic lessons, but what jumped out at me was that if you don’t know it, you don’t know it, and you can’t diagnose it,’’ he says. “And that gives you a sense of confidence that you’ve covered everything.”

No one had a familiarity with the subtle manifestations of that diagnosis until Dr. Li stepped in. “One lesson is that if you think the patient is on the up and up, and you haven’t yet made a diagnosis,” says Dr. Feinbloom, “it doesn’t mean there’s no diagnosis to be made.”

Dr. Li gives this lesson to his students this way: You may not have seen diagnosis X, but has diagnosis X seen you?

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493-1499.

- Wachter RM. Is ambulatory patient safety just like hospital safety, only without the ‘‘stat’’? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):547-549.

- Schiff GD, Kim S, Abrams R, et al. Diagnosing diagnosis errors: lessons from a multi-institutional collaborative project. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ Publication No.050021-2.); 2005.

- Kempainen RR, Migeon MB, Wolf FM. Understanding our mistakes: a primer on errors in clinical reasoning. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):177-181.

- Redelmeier DA. Improving patient care. The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(2):115-120.

- Damasio AR. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons; 1995.

This is the first of a two-part series examining medical errors. This article addresses thought processes hospitalists use that may lead to mistaken diagnoses. Part 2 will look at what healthcare corporations are doing to improve diagnoses and reduce errors.

When talking about tough diagnoses, academic hospitalist David Feinbloom, MD, recalls the story of a female patient seen by his hospitalist group whose diagnosis took some time to nail down.

This woman had been in and out of the hospital for several years with nonspecific abdominal pain and intermittent diarrhea. She had been seen by numerous doctors and tested extensively. Increasingly her doctors concluded that there was some psychiatric overlay—she was depressed or somatic.

“Patients like these are very common and often end up on the hospitalist service,” says Dr. Feinbloom, who works at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

But to Joseph Li, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel, this patient seemed normal. There was something about the symptoms she described that reminded him of a patient he had seen who had been diagnosed with a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Although this patient’s past MRI had been negative, Dr. Li remembered that if you don’t perform the right MRI protocol, you’ll miss something. He asked the team to obtain a panel looking for specific markers and to repeat the MRI with the correct protocol. It was accepted as fact that there was no pathology to explain her symptoms but that she had had every test. He requested another gastrointestinal (GI) consult.

“It seemed so far out there, and then everything he said was completely correct,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “She had Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.”

Clues from Sherlock

In his book How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, discusses Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, physician and creator of the brilliant detective Sherlock Holmes. When it comes to solving crimes, Holmes’ superior observation and logic, intellectual prowess, and pristine reasoning help him observe and interpret the most obscure and arcane clues. He is, in the end, a consummate diagnostician.

One of the first rules a great diagnostician must follow is to not get boxed into one way of thinking, says Dr. Groopman, the Dina and Raphael Recanati chair of medicine at the Harvard Medical School and chief of experimental medicine at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. That is one of the downsides of a too-easy attachment to using clinical practice guidelines, he says.

“Guidelines are valuable reference points, but in order to use a guideline effectively, you have to have the correct diagnosis,” he says. “Studies over decades with hospitalized patients show that the misdiagnosis rate is at least 15% and hasn’t changed.1 A great deal of effort needs to be put into improving our accuracy in making diagnoses.”

Compared with other kinds of medical errors, diagnostic errors have not gotten a great deal of attention. The hospital patient safety movement has been more focused on preventing medication errors, surgical errors, handoff communications, nosocomial infections, falls, and blood clots.2 There have been few studies pertaining exclusively to diagnostic errors—but the topic is gaining headway.3

Think about Thinking

Diagnostic errors are usually multifactorial in origin and typically involve system-related and individual factors. The systems-based piece includes environmental and organizational factors. Medical researchers conclude the majority of diagnostic errors arise from flaws in physician thinking, not technical mistakes.

Cognitive errors involve instances where knowledge, data gathering, data processing, or verification (such as by lab testing) are faulty. Improving diagnostics will require better accountability by institutions and individuals. To do the latter, experts say, physicians would do well to familiarize themselves with their diagnostic weaknesses.

Thinking about thinking is the science of cognitive psychology and addresses the cognitive aspects of clinical reasoning underlying diagnostic decision-making. It is an area of study in which few medical professionals are versed. “Except for a few of these guys who trained in psych or were voices in the wilderness that have been largely ignored,” most physicians are unaware of the cognitive psychology literature, Dr. Groopman says.

Common biases and errors in clinical reasoning are presented in Table 1 (right).4,5 These are largely individual mistakes for which physicians traditionally have been accountable.

Patterns and Heuristics

The following factors contribute to how shortcuts are used: the pressures of working in medicine, the degrees of uncertainty a physician may feel, and the fact that hospitalists rarely have all the information they need about a patient.

“That’s just the nature of medicine,” says Dr. Groopman. “These shortcuts are natural ways of thinking under those conditions. They succeed about 85% of the time; they fail up to 10-20% of the time. The first thing we need to educate ourselves about is that this is how our minds work as doctors.”

Dr. Groopman and those he interviewed for his book have a razor-sharp overview of clinical practice within hospitals throughout the U.S. and Canada, including academic centers, community centers, affluent areas, suburbs, inner cities, and Native American reservations. But except for Pat Croskerry, MD, PhD, in the department of emergency medicine at Dalhousie University’s Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center in Halifax, Nova Scotia, none of the experts he interviewed had rigorous training in cognitive science.

Although how to think is a priority in physicians’ training, how to think about one’s thinking is not.

“We are not given a vocabulary during medical training, or later through CME courses, in this emerging science—and yet this science involves how our mind works successfully and when we make mistakes,” Dr. Groopman says.

The data back this assertion. In a study of 100 cases of diagnostic error, 90 involved injury, including 33 deaths; 74% were attributed to errors in cognitive reasoning (see Figure 1, right).1 Failure to consider reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis was the most common cause. Other common causes included faulty context generation, misjudging the salience of findings, faulty perception, and errors connected with the use of heuristics. In this study, faulty or inadequate knowledge was uncommon.

Underlying contributions to error fell into three categories: “no fault,” system-related, and cognitive. Only seven cases reflected no-fault errors alone. In the remaining 93 cases, 548 errors were identified as system-related or cognitive factors (5.9 per case). System-related factors contributed to the diagnostic error in 65% of the cases and cognitive factors in 74%. The most common system-related factors involved problems with policies and procedures, inefficient processes, teamwork, and communication. The most common cognitive problems involved faulty synthesis.

Dr. Groopman believes it is important for physicians to be more introspective about the thinking patterns they employ and learn the traps to which they are susceptible. He also feels it is imperative to develop curricula at different stages of medical training so this new knowledge can be used to reduce error rates. Because the names for these traps can vary, the development of a universal and comprehensive taxonomy for classifying diagnostic errors is also needed.

“It’s impossible to be perfect; we’re never going to be 100%,” Dr. Groopman says. “But I deeply believe that it is quite feasible to think about your thinking and to assess how your mind came to a conclusion about a diagnosis and treatment plan.”

When phy-sicians think about errors in cognitive reasoning, they often focus on the “don’t-miss diagnoses” or the uncommon variant missed by recall or anchoring errors.

“When I reflect on the errors I have made, they mostly fall into the categories that Dr. Groopman describes in his book,” Dr. Feinbloom says. “Interestingly, the errors that I see most often stem from the fear of making an error of omission.”

It is paradoxical, but in order to ensure that no possible diagnosis is missed, doctors often feel the need to rule out all possible diagnoses.

“While it makes us feel that we are doing the best for our patients, this approach leads to an inordinate amount of unnecessary testing and potentially harmful interventions,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “Understanding how cognitive errors occur should allow us to be judicious in our approach, with the confidence to hold back when the diagnosis is clear, and push harder when we know that something does not fit.”

Emotional Dimension

Although many diagnostic errors are attributable to mistakes in thinking, emotions, and feelings—which may not be easy to detect or admit—also contribute to decision-making.

As hypothesized by noted neurologist and author Antonio Damasio in Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, some feelings—visceral signals he calls somatic markers—deter us from or attract us to certain images and decisions.6 Remaining cognizant of those feelings helps clarify how they may inform a medical decision—for good and bad.

The emotional dimension of decision-making cannot be disregarded, says Dr. Groopman. “We need to take our emotional temperature; there are patients we like more and patients we like less,” he says. “There are times when we are tremendously motivated to succeed with a very complicated and daunting patient in the hospital, and there are times when we retreat from that for whatever psychological reason. Sometimes it’s fear of failure, sometimes it’s stereotyping. Regardless, we need to have a level of self-awareness.”

The stressful atmosphere of hospital-based medicine contributes to a high level of anxiety. “Physicians use a telegraphic language full of sound bytes with each other that may contribute to the way heuristics are passed from one generation of doctors to the next,” Dr. Groopman says. “That language is enormously powerful in guiding our thinking and the kinds of shortcuts that we use.”

Pitfalls in Reasoning

Of all the bias errors in clinical reasoning, two of the most influential on physicians are anchoring and attribution. Bound-ed rationality—the failure to continue considering reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis is reached—is also a pitfall. The difference between the latter and anchoring is whether the clinician adjusts the diagnosis when new data emerge.

Anchoring errors may arise from seizing the first bits of data and allowing them to guide all future questioning. “It happens every day,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “The diagnosis kind of feels right. There is something about the speed with which it comes to mind, the familiarity with the diagnosis in question, [that] reinforces your confidence.”

Dr. Feinbloom teaches his young trainees to trust no one. “I mean that in a good-hearted way,” he says. “Never assume what you’re told is accurate. You have to review everything yourself, interview the patient again; skepticism is a powerful tool.”

With the woman who was ultimately diagnosed with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, Dr. Li’s skepticism paid off—and the hospitalist team benefited from deconstructing its clinical thinking to see where it went awry.

“If someone had gotten the gastrin level earlier,” says Dr. Feinbloom, “they would have caught it, but it was not on anyone’s radar. When imaging was negative, the team assumed it wasn’t a tumor.”

Lessons Learned

There are lots of lessons here, says Dr. Feinbloom. “You could spin it any one of five different ways with heuristic lessons, but what jumped out at me was that if you don’t know it, you don’t know it, and you can’t diagnose it,’’ he says. “And that gives you a sense of confidence that you’ve covered everything.”

No one had a familiarity with the subtle manifestations of that diagnosis until Dr. Li stepped in. “One lesson is that if you think the patient is on the up and up, and you haven’t yet made a diagnosis,” says Dr. Feinbloom, “it doesn’t mean there’s no diagnosis to be made.”

Dr. Li gives this lesson to his students this way: You may not have seen diagnosis X, but has diagnosis X seen you?

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493-1499.

- Wachter RM. Is ambulatory patient safety just like hospital safety, only without the ‘‘stat’’? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):547-549.

- Schiff GD, Kim S, Abrams R, et al. Diagnosing diagnosis errors: lessons from a multi-institutional collaborative project. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ Publication No.050021-2.); 2005.

- Kempainen RR, Migeon MB, Wolf FM. Understanding our mistakes: a primer on errors in clinical reasoning. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):177-181.

- Redelmeier DA. Improving patient care. The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(2):115-120.

- Damasio AR. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons; 1995.

This is the first of a two-part series examining medical errors. This article addresses thought processes hospitalists use that may lead to mistaken diagnoses. Part 2 will look at what healthcare corporations are doing to improve diagnoses and reduce errors.

When talking about tough diagnoses, academic hospitalist David Feinbloom, MD, recalls the story of a female patient seen by his hospitalist group whose diagnosis took some time to nail down.

This woman had been in and out of the hospital for several years with nonspecific abdominal pain and intermittent diarrhea. She had been seen by numerous doctors and tested extensively. Increasingly her doctors concluded that there was some psychiatric overlay—she was depressed or somatic.

“Patients like these are very common and often end up on the hospitalist service,” says Dr. Feinbloom, who works at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

But to Joseph Li, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel, this patient seemed normal. There was something about the symptoms she described that reminded him of a patient he had seen who had been diagnosed with a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Although this patient’s past MRI had been negative, Dr. Li remembered that if you don’t perform the right MRI protocol, you’ll miss something. He asked the team to obtain a panel looking for specific markers and to repeat the MRI with the correct protocol. It was accepted as fact that there was no pathology to explain her symptoms but that she had had every test. He requested another gastrointestinal (GI) consult.

“It seemed so far out there, and then everything he said was completely correct,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “She had Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.”

Clues from Sherlock

In his book How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, discusses Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, physician and creator of the brilliant detective Sherlock Holmes. When it comes to solving crimes, Holmes’ superior observation and logic, intellectual prowess, and pristine reasoning help him observe and interpret the most obscure and arcane clues. He is, in the end, a consummate diagnostician.

One of the first rules a great diagnostician must follow is to not get boxed into one way of thinking, says Dr. Groopman, the Dina and Raphael Recanati chair of medicine at the Harvard Medical School and chief of experimental medicine at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. That is one of the downsides of a too-easy attachment to using clinical practice guidelines, he says.

“Guidelines are valuable reference points, but in order to use a guideline effectively, you have to have the correct diagnosis,” he says. “Studies over decades with hospitalized patients show that the misdiagnosis rate is at least 15% and hasn’t changed.1 A great deal of effort needs to be put into improving our accuracy in making diagnoses.”

Compared with other kinds of medical errors, diagnostic errors have not gotten a great deal of attention. The hospital patient safety movement has been more focused on preventing medication errors, surgical errors, handoff communications, nosocomial infections, falls, and blood clots.2 There have been few studies pertaining exclusively to diagnostic errors—but the topic is gaining headway.3

Think about Thinking

Diagnostic errors are usually multifactorial in origin and typically involve system-related and individual factors. The systems-based piece includes environmental and organizational factors. Medical researchers conclude the majority of diagnostic errors arise from flaws in physician thinking, not technical mistakes.

Cognitive errors involve instances where knowledge, data gathering, data processing, or verification (such as by lab testing) are faulty. Improving diagnostics will require better accountability by institutions and individuals. To do the latter, experts say, physicians would do well to familiarize themselves with their diagnostic weaknesses.

Thinking about thinking is the science of cognitive psychology and addresses the cognitive aspects of clinical reasoning underlying diagnostic decision-making. It is an area of study in which few medical professionals are versed. “Except for a few of these guys who trained in psych or were voices in the wilderness that have been largely ignored,” most physicians are unaware of the cognitive psychology literature, Dr. Groopman says.

Common biases and errors in clinical reasoning are presented in Table 1 (right).4,5 These are largely individual mistakes for which physicians traditionally have been accountable.

Patterns and Heuristics

The following factors contribute to how shortcuts are used: the pressures of working in medicine, the degrees of uncertainty a physician may feel, and the fact that hospitalists rarely have all the information they need about a patient.

“That’s just the nature of medicine,” says Dr. Groopman. “These shortcuts are natural ways of thinking under those conditions. They succeed about 85% of the time; they fail up to 10-20% of the time. The first thing we need to educate ourselves about is that this is how our minds work as doctors.”

Dr. Groopman and those he interviewed for his book have a razor-sharp overview of clinical practice within hospitals throughout the U.S. and Canada, including academic centers, community centers, affluent areas, suburbs, inner cities, and Native American reservations. But except for Pat Croskerry, MD, PhD, in the department of emergency medicine at Dalhousie University’s Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center in Halifax, Nova Scotia, none of the experts he interviewed had rigorous training in cognitive science.

Although how to think is a priority in physicians’ training, how to think about one’s thinking is not.

“We are not given a vocabulary during medical training, or later through CME courses, in this emerging science—and yet this science involves how our mind works successfully and when we make mistakes,” Dr. Groopman says.

The data back this assertion. In a study of 100 cases of diagnostic error, 90 involved injury, including 33 deaths; 74% were attributed to errors in cognitive reasoning (see Figure 1, right).1 Failure to consider reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis was the most common cause. Other common causes included faulty context generation, misjudging the salience of findings, faulty perception, and errors connected with the use of heuristics. In this study, faulty or inadequate knowledge was uncommon.

Underlying contributions to error fell into three categories: “no fault,” system-related, and cognitive. Only seven cases reflected no-fault errors alone. In the remaining 93 cases, 548 errors were identified as system-related or cognitive factors (5.9 per case). System-related factors contributed to the diagnostic error in 65% of the cases and cognitive factors in 74%. The most common system-related factors involved problems with policies and procedures, inefficient processes, teamwork, and communication. The most common cognitive problems involved faulty synthesis.

Dr. Groopman believes it is important for physicians to be more introspective about the thinking patterns they employ and learn the traps to which they are susceptible. He also feels it is imperative to develop curricula at different stages of medical training so this new knowledge can be used to reduce error rates. Because the names for these traps can vary, the development of a universal and comprehensive taxonomy for classifying diagnostic errors is also needed.

“It’s impossible to be perfect; we’re never going to be 100%,” Dr. Groopman says. “But I deeply believe that it is quite feasible to think about your thinking and to assess how your mind came to a conclusion about a diagnosis and treatment plan.”

When phy-sicians think about errors in cognitive reasoning, they often focus on the “don’t-miss diagnoses” or the uncommon variant missed by recall or anchoring errors.

“When I reflect on the errors I have made, they mostly fall into the categories that Dr. Groopman describes in his book,” Dr. Feinbloom says. “Interestingly, the errors that I see most often stem from the fear of making an error of omission.”

It is paradoxical, but in order to ensure that no possible diagnosis is missed, doctors often feel the need to rule out all possible diagnoses.

“While it makes us feel that we are doing the best for our patients, this approach leads to an inordinate amount of unnecessary testing and potentially harmful interventions,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “Understanding how cognitive errors occur should allow us to be judicious in our approach, with the confidence to hold back when the diagnosis is clear, and push harder when we know that something does not fit.”

Emotional Dimension

Although many diagnostic errors are attributable to mistakes in thinking, emotions, and feelings—which may not be easy to detect or admit—also contribute to decision-making.

As hypothesized by noted neurologist and author Antonio Damasio in Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, some feelings—visceral signals he calls somatic markers—deter us from or attract us to certain images and decisions.6 Remaining cognizant of those feelings helps clarify how they may inform a medical decision—for good and bad.

The emotional dimension of decision-making cannot be disregarded, says Dr. Groopman. “We need to take our emotional temperature; there are patients we like more and patients we like less,” he says. “There are times when we are tremendously motivated to succeed with a very complicated and daunting patient in the hospital, and there are times when we retreat from that for whatever psychological reason. Sometimes it’s fear of failure, sometimes it’s stereotyping. Regardless, we need to have a level of self-awareness.”

The stressful atmosphere of hospital-based medicine contributes to a high level of anxiety. “Physicians use a telegraphic language full of sound bytes with each other that may contribute to the way heuristics are passed from one generation of doctors to the next,” Dr. Groopman says. “That language is enormously powerful in guiding our thinking and the kinds of shortcuts that we use.”

Pitfalls in Reasoning

Of all the bias errors in clinical reasoning, two of the most influential on physicians are anchoring and attribution. Bound-ed rationality—the failure to continue considering reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis is reached—is also a pitfall. The difference between the latter and anchoring is whether the clinician adjusts the diagnosis when new data emerge.

Anchoring errors may arise from seizing the first bits of data and allowing them to guide all future questioning. “It happens every day,” says Dr. Feinbloom. “The diagnosis kind of feels right. There is something about the speed with which it comes to mind, the familiarity with the diagnosis in question, [that] reinforces your confidence.”

Dr. Feinbloom teaches his young trainees to trust no one. “I mean that in a good-hearted way,” he says. “Never assume what you’re told is accurate. You have to review everything yourself, interview the patient again; skepticism is a powerful tool.”

With the woman who was ultimately diagnosed with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, Dr. Li’s skepticism paid off—and the hospitalist team benefited from deconstructing its clinical thinking to see where it went awry.

“If someone had gotten the gastrin level earlier,” says Dr. Feinbloom, “they would have caught it, but it was not on anyone’s radar. When imaging was negative, the team assumed it wasn’t a tumor.”

Lessons Learned

There are lots of lessons here, says Dr. Feinbloom. “You could spin it any one of five different ways with heuristic lessons, but what jumped out at me was that if you don’t know it, you don’t know it, and you can’t diagnose it,’’ he says. “And that gives you a sense of confidence that you’ve covered everything.”

No one had a familiarity with the subtle manifestations of that diagnosis until Dr. Li stepped in. “One lesson is that if you think the patient is on the up and up, and you haven’t yet made a diagnosis,” says Dr. Feinbloom, “it doesn’t mean there’s no diagnosis to be made.”

Dr. Li gives this lesson to his students this way: You may not have seen diagnosis X, but has diagnosis X seen you?

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493-1499.

- Wachter RM. Is ambulatory patient safety just like hospital safety, only without the ‘‘stat’’? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):547-549.

- Schiff GD, Kim S, Abrams R, et al. Diagnosing diagnosis errors: lessons from a multi-institutional collaborative project. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ Publication No.050021-2.); 2005.

- Kempainen RR, Migeon MB, Wolf FM. Understanding our mistakes: a primer on errors in clinical reasoning. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):177-181.

- Redelmeier DA. Improving patient care. The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(2):115-120.

- Damasio AR. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons; 1995.