User login

Aggression, irritability, repetitive phenomena, or hyperactivity can interfere with the education and treatment of patients with autism.1 To assist clinicians in selecting drug therapies to control these behaviors, we developed a medication strategy based on controlled studies and our experience in an autism specialty clinic. In this article, we:

- offer an overview with two algorithms that show how to target maladaptive behaviors in patients of all ages with autism

- and discuss the controlled clinical evidence behind this approach.

Targeting behaviors

A multimodal approach is used to manage autistic disorder. Although behavioral techniques are useful and may decrease the need for drug therapy, one or more medications are often required to target severe maladaptive behaviors. Although we recommend that you consider all interfering behaviors when selecting medications, it is important to:

- initially focus on symptoms—such as self-injurious behaviors and aggression—that acutely affect the patient’s and caregiver’s safety

- consider the patient as being pre- or postpubertal, as developmental level may affect medication response.

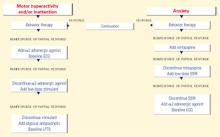

Figure 1 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Aggression or self-injury. When drug therapy is needed to control severe aggression or self-injurious behavior, we recommend a trial of an atypical antipsychotic for prepubertal patients (Figure 1). Alternately, you may consider a mood stabilizer such as lithium or divalproex for an adult patient with prominent symptoms (Figure 2). However, mood stabilizer use requires monitoring by venipuncture for potential blood cell or liver function abnormalities.

Atypical antipsychotics are associated with adverse effects including sedation, weight gain, extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and hyperprolactinemia. Therefore, you may need to monitor weight, lipid profile, glucose, liver function, and cardiac function when using this class of agent.

Repetitive phenomena can be addressed with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although SSRIs may be activating in children and tend to be better tolerated in older adolescents and adults.

Anxiety. In children with anxiety, we suggest a trial of mirtazapine—because of its calming properties—before you try an SSRI. If both the SSRI and mirtazapine are ineffective, try an α2-adrenergic agonist. A baseline ECG is recommended before starting an α2-adrenergic agonist—particularly clonidine, which has been associated with rare cardiovascular events. Overall, these agents are well tolerated.

Hyperactivity, inattention. Anecdotal evidence indicates that stimulants may worsen symptoms of aggression, hyperactivity, and irritability in individuals with autism. Therefore, we suggest you start with an α2-adrenergic agonist when target symptoms include hyperactivity and inattention. Consider a stimulant trial if the α2-adrenergic agonist does not control the symptoms.

An atypical antipsychotic is generally recommended for autistic individuals with treatment-resistant hyperactivity and inattention, anxiety, and interfering repetitive behaviors.

Drug therapy. As summarized below, controlled evidence for behavior-based drug therapy of autism (Table.) suggests a role for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and psychostimulants in managing interfering behaviors.

Antipsychotics

Risperidone. Two controlled studies have reported the effect of risperidone on autism’s related symptoms.

McDougle et al conducted a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone, mean 2.9 mg/d, in adults with pervasive developmental disorders.2 Repetitive behavior, aggression, anxiety, irritability, depression, and general behavioral symptoms decreased in 8 of 14 patients, as measured by Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Sixteen subjects who received placebo showed no response. Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect.

More recently, the National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone, 0.5 to 3.5 mg/d (mean 1.8 mg/d), in 101 children and adolescents with autism.3 After 8 weeks, 69% of the risperidone group responded, compared with 12% of the placebo group. Response was defined as:

- at least a 25% decrease in the Irritability subscale score of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC)

- and CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”

Risperidone was effective for treating aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, and repetitive behavior. Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 2.7 kg vs. 0.8 kg with placebo), increased appetite, sedation, dizziness, and hypersalivation.

Olanzapine. A 12-week, open-label study of olanzapine, mean 7.8 mg/d, was conducted in eight patients ages 5 to 42 diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder.4 Hyperactivity, social relatedness, self-injurious behavior, aggression, anxiety, and depression improved significantly in six of seven patients who completed the trial, as measured by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 18.4 lbs) in six patients and sedation in three.

Malone et al conducted a 6-week, open-label comparison of olanzapine, mean 7.9 mg/d, versus haloperidol, mean 1.4 mg/d, in 12 children with autistic disorder.5 Five of six subjects who received olanzapine responded, compared with three of six who received haloperidol, as determined by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Anger/uncooperativeness and hyperactivity were reduced significantly only in the olanzapine group. Weight gain and sedation were the most common adverse effects with both medications. Weight gain was greater with olanzapine (mean 9 lbs) than with haloperidol (mean 3.2 lbs).

Quetiapine. Only one report addresses quetiapine in children and adolescents with autism.6 Two of six patients completed this 16-week, open-label trial of quetiapine, 100 to 350 mg/d (1.6 to 5.2 mg/kg/d). The group showed no statistically significant improvement in behavioral symptoms. Two patients achieved CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” One subject dropped out after a possible seizure during treatment, and three others withdrew because of sedation or lack of response.

Ziprasidone. McDougle et al conducted a naturalistic, open-label study of ziprasidone, 20 to 120 mg/d (mean 59.2 mg/d), in 12 subjects ages 8 to 20. Nine were diagnosed with autism and three with a pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). Six subjects responded across 14 weeks of treatment, as determined by ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI.7

Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect. Mean weight change was −5.83 lbs (range −35 to +6 lbs). Despite ziprasidone’s reported risk of causing abnormal cardiac rhythms, no cardiovascular adverse effects were reported.

Clozapine. Three case reports but no controlled studies have addressed clozapine in autistic disorder:

- Zuddas et al used clozapine, 100 to 200 mg/d for 3 months, to treat three children ages 8 to 12.8 Previous trials of haloperidol were ineffective, but the patients’ aggression, hyperactivity, negativism, and language and communication skills improved with clozapine, as measured by the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale (CPRS) and the Self-Injurious Behavior Questionnaire.

- Chen et al used clozapine, 275 mg/d, to treat a 17-year-old male inpatient.9 Aggression was significantly reduced across 15 days, as determined by a 21-question modified version of the CPRS. Side effects included mild constipation and excessive salivation.

- Clozapine, 300 mg/d for 2 months, reduced aggression in an adult patient and was associated with progressive and marked improvement of aggression and social interaction, as measured by the CGI and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). No agranulocytosis or extrapyramidal symptoms were observed across 5 years of therapy.10

Clozapine’s adverse effect profile probably explains why the literature contains so little data regarding its use in patients with autism. This drug’s propensity to lower the seizure threshold discourages its use in a population predisposed to seizures. Autistic patients also have a low tolerance for frequent venipuncture and limited ability to communicate agranulocytosis symptoms.

Antidepressants

Clomipramine—a tricyclic antidepressant with anti-obsessional properties—has shown some positive effects in treating autistic behaviors. Even so, this compound is prescribed infrequently to patients with autism because of low tolerability. In one recent double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study, 36 autistic patients ages 10 to 36 received:

- clomipramine, 100 to 150 mg/d (mean 128 mg/d)

- haloperidol, 1 to 1.5 mg/d (mean 1.3 mg/d)

or placebo for 7 weeks. Among patients who completed the trial, clomipramine and haloperidol were similarly effective in reducing overall autistic symptoms, irritability, and stereotypy. However, only 37.5% of those receiving clomipramine completed the study because of adverse effects, behavioral problems, and general lack of efficacy.11

Table

CONTROLLED EVIDENCE* FOR BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY OF AUTISM

| Medication | Behaviors improved | Significant adverse effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone 2 | Aggression, irritability | Mild transient sedation | Conducted in adults |

| Risperidone 3 | Aggression, irritability | Weight gain, increased appetite, sedation, tremor, hypersalivation | Largest controlled study to date in children with autism |

| Clomipramine 11 | Irritability, stereotypy | Tachycardia, tremors, diaphoresis, insomnia, nausea | Conducted in children and adults |

| Fluvoxamine 12 | Aggression, repetitive phenomena | Nausea, sedation | No published controlled pediatric data; unpublished pediatric data unfavorable |

| Clonidine 24 | Hyperactivity, irritability, stereotypies, oppositional behavior, aggression, self-injury | Hypotension, sedation, decreased activity | Small number of subjects |

| Clonidine 25 | Impulsivity, self-stimulation, hyperarousal | Sedation and fatigue | Small number of subjects |

| Methylphenidate 28 | Hyperactivity, irritability | Social withdrawal and irritability | Adverse effects more common at 0.6 mg/kg/dose |

| • Double-blind, placebo-controlled studies | |||

Fluvoxamine. Only one double-blind, placebo-controlled study has examined the use of an SSRI in autistic disorder.12 In this 12-week trial, 30 adults with autism received fluvoxamine, mean 276.7 mg/d, or placebo. Eight of 15 subjects in the fluvoxamine group were categorized as “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI.

Fluvoxamine was much more effective than placebo in reducing repetitive thoughts and behavior, aggression, and maladaptive behavior. Adverse effects included minimal sedation and nausea.

Unpublished data of McDougle et al suggest that autistic children and adolescents respond less favorably than adults to fluvoxamine. In a 12-week, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial in patients ages 5 to 18, only 1 of 18 subjects responded to fluvoxamine at a mean dosage of 106.9 mg/d. Agitation, increased aggression, hyperactivity, and increased repetitive behavior were reported.

Fluoxetine. Seven autistic patients ages 9 to 20 were treated with fluoxetine, 20 to 80 mg/d (mean 37.1 mg/d) in an 18-month longitudinal open trial. Irritability, lethargy, and stereotypy improved, as measured by the ABC.13 Adverse effects included increased hyperactivity and transient appetite suppression.

In another open-label trial of 37 autistic children ages 2 to 7, response was rated by investigators as “excellent” in 11 and “good” in another 11 who received fluoxetine, 0.2 to 1.4 mg/kg/d. However, aggression was a frequent cause for drug discontinuation during the 21-month study.14

Sertraline. In an open-label trial, Steingard et al treated nine autistic children ages 6 to 12 with sertraline, 25 to 50 mg/d for 2 to 8 weeks. Clinical improvement was observed in irritability, transition-associated anxiety, and need for sameness in eight of the children.15

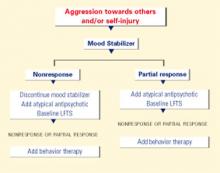

Figure 2 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR POSTPUBERTAL PATIENTS WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc.In an open-label trial, 42 adults with pervasive developmental disorders were treated for 12 weeks with sertraline, 50 to 200 mg/d (mean 122 mg/d). Twenty-four (57%) achieved CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” in aggressive and repetitive behavior.16

Paroxetine. Fifteen adults with profound mental retardation (including seven with pervasive developmental disorders) received paroxetine, 10 to 50 mg/d (mean 35 mg/d) in a 4-month open-label trial. Frequency and severity of aggression were rated as improved after 1 month, but not at 4 months.17

Mirtazapine. In an open-label trial, 26 patients ages 3 to 23 with pervasive developmental disorders were treated with mirtazapine, 7.5 to 45 mg/d (mean 30.3 mg/d). Aggression, self-injury, irritability, hyperactivity, anxiety, depression, and insomnia decreased in 9 patients (34%), as determined by ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI. Adverse effects included increased appetite and transient sedation.18

Mood stabilizers

Lithium. No recent studies of lithium in pervasive developmental disorders are known to exist, but several case reports have been published:

- two reports found lithium decreased manic symptoms in individuals with autism and a family history of bipolar disorder19,20

- one report of lithium augmentation of fluvoxamine in an adult with autistic disorder noted markedly improved aggression and impulsivity after 2 weeks of treatment, as measured by the CGI, Brown Aggression Scale, and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale.21

Divalproex. In an open-label trial, 14 subjects ages 5 to 40 with pervasive developmental disorders were given divalproex sodium, 125 to 2,500 mg/d (mean 768 mg/d; mean blood level 75.8 mcg/mL. Affective instability, repetitive behavior, impulsivity, and aggression improved in 10 patients (71%), as measured by CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”22 Adverse effects included sedation, weight gain, hair loss, behavioral activation, and elevated liver enzymes.

Lamotrigine. In a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, lamotrigine, 5.0 mg/kg/d, was given to 14 children ages 3 to 11 with autistic disorder.23 Lamotrigine and placebo showed no significant differences in effect, as measured by the ABC, Autism Behavior Checklist, Vineland scales, Childhood Autism Rating Scale, and PreLinguistic Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale. Insomnia and hyperactivity were the most common adverse effects.

α2-adrenergic agonists

Clonidine. Jaselskis et al administered clonidine, 4 to 10 mcg/kg/d, to eight children ages 5 to 13 with autism in a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.24 Symptoms of hyperactivity, irritability, and oppositional behavior improved, as determined by teacher ratings on the ABC, Conners Abbreviated Parent-Teacher Questionnaire, and Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity Comprehensive Teacher’s Rating Scale. Adverse effects included hypotension, sedation, and decreased activity.

Nine autistic patients ages 5 to 33 received transdermal clonidine, 0.16 to 0.48 mcg/kg/d (mean 3.6 mcg/kg/d), in a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Hyperarousal, impulsivity, and self-stimulation improved, as measured by the Ritvo-Freeman Real Life Rating Scale and the CGI. Sedation and fatigue were reported, especially during the first 2 weeks of treatment.25

Guanfacine. The effect of guanfacine, 0.25 to 9.0 mg/d (mean 2.6 mg/d), was examined retrospectively in 80 children and adolescents ages 3 to 18 with pervasive developmental disorders.26 Hyperactivity, inattention, and tics improved in the 19 subjects (23.8%) who were rated “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI. Sedation was the most frequently reported adverse effect.

Psychostimulants

Early reports showed little benefit from stimulants in pervasive developmental disorders, but more recent studies suggest a modest effect. The RUPP Autism Network is conducting a large controlled investigation of methylphenidate to better understand the role of stimulants in children and adolescents in this diagnostic cluster.

Quintana et al conducted a double-blind, crossover study of methylphenidate, 10 or 20 mg bid for 2 weeks, in 10 children ages 7 to 11 with autism.27 Although irritability and hyperactivity showed statistically significant improvement as determined by the ABC and Conners Teacher Questionnaire, the authors reported only modest clinical effects. More recently, use of methylphenidate, 0.3 and 0.6 mg/kg/dose, was associated with a 50% decrease on the Connors Hyperactivity Index in 8 of 13 autistic children ages 5 to 11.28 Adverse effects—most common with the 0.6 mg/kg/dose—included social withdrawal and irritability in this double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.

Related resources

- McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, Charney DS, Leckman JF (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: Principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C (eds). Neuropsychopharmacology: the fifth generation of progress. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Autism booklet. www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/autism.cfm

- Autism Society of America. www.autism-society.org

Drug brand names

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Guanfacine • Tenex

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Stigler reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Posey receives grant support from and is a consultant to Eli Lilly & Co.

Dr. McDougle receives grant support from and is a consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly & Co., and Janssen Pharmaceutica, and is a speaker for Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Daniel X. Freedman Psychiatric Research Fellowship Award (Dr. Posey), a National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (Dr. Posey), a Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology contract (N01MH70001) from the National Institute of Mental Health to Indiana University (Drs. McDougle and Posey), a National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center grant to Indiana University (M01-RR00750), and a Department of Housing and Urban Development grant (B-01-SP-IN-0200).

1. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

2. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, Pelton GH, Cohen DJ, Price LH. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:633-41.

3. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 2002;347(5):314-21.

4. Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, McDougle CJ. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: An open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999;19:37-44.

5. Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, Choudhury MS, Delaney MA. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(8):887-94.

6. Martin A, Koenig K, Scahill L, Bregman J. Open-label quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999;9:99-107.

7. McDougle CJ, Kem DL, Posey DJ. Case series: use of ziprasidone for maladaptive symptoms in youths with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41(8):921-7.

8. Zuddas A, Ledda MG, Fratta A, Muglia P, Cianchetti C. Clinical effects of clozapine on autistic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153(5):738.-

9. Chen NC, Bedair HS, McKay B, Bowers MB, Mazure C. Clozapine in the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(6):479-80.

10. Gobbi G, Pulvirenti L. Long-term treatment with clozapine in an adult with autistic disorder accompanied by aggressive behaviour. J Psych Neurol 2001;26(4):340-1.

11. Remington G, Sloman L, Konstantareas M, Parker K, Gow R. Clomipramine versus haloperidol in the treatment of autistic disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21(4):440-4.

12. McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, Heninger GR, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:1001-8.

13. Fatemi SH, Realmuto GM, Khan L, Thuras P. Fluoxetine in treatment of adolescent patients with autism: a longitudinal open trial. J Autism Dev Disord 1998;28(4):303-7.

14. DeLong GR, Teague LA, Kamran MM. Effects of fluoxetine treatment in young children with idiopathic autism. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:551-62.

15. Steingard RJ, Zimnitzky B, DeMaso DR, Bauman ML, Bucci JP. Sertraline treatment of transition-associated anxiety and agitation in children with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997;7(1):9-15.

16. McDougle CJ, Brodkin ES, Naylor ST, Carlson DC, Cohen DJ, Price LH. Sertraline in adults with pervasive developmental disorders: a prospective open-label investigation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18:62-6.

17. Davanzo PA, Belin TR, Widawski MH, King BH. Paroxetine treatment of aggression and self-injury in persons with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 1998;102(5):427-37.

18. Posey DJ, Guenin KD, Kohn AE, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. A naturalistic open-label study of mirtazapine in autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001;11(3):267-77.

19. Kerbeshian J, Burd L, Fisher W. Lithium carbonate in the treatment of two patients with infantile autism and atypical bipolar symptomatology. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987;7(6):401-5.

20. Steingard R, Biederman J. Lithium-responsive manic-like symptoms in two individuals with autism and mental retardation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987;26:932-5.

21. Epperson CN, McDougle CJ, Anand A, et al. Lithium augmentation of fluvoxamine in autistic disorder: a case report. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1994;4:201-7.

22. Hollander E, Dolgoff-Kaspar R, Cartwright C, Rawitt R, Novotny S. An open trial of divalproex sodium in autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(7):530-4.

23. Belsito KM, Law PA, Kirk KS, Landa RJ, Zimmerman AW. Lamotrigine therapy for autistic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31(2):175-81.

24. Jaselskis CA, Cook EH, Fletcher KE, Leventhal BL. Clonidine treatment of hyperactive and impulsive children with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12(5):322-7.

25. Fankhauser MP, Karumanchi VC, German ML, Yates A, Karumanchi SD. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of transdermal clonidine in autism. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53(3):77-82.

26. Posey DJ, Decker J, Sasher TM, Kohburn A, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. A retrospective analysis of guanfacine in the treatment of autism. New Orleans: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2001; new research abstracts no. 816.

27. Quintana H, Birmaher B, Stedge D, et al. Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 1995;25(3):283-95.

28. Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M. Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2000;30(3):245-55.

Aggression, irritability, repetitive phenomena, or hyperactivity can interfere with the education and treatment of patients with autism.1 To assist clinicians in selecting drug therapies to control these behaviors, we developed a medication strategy based on controlled studies and our experience in an autism specialty clinic. In this article, we:

- offer an overview with two algorithms that show how to target maladaptive behaviors in patients of all ages with autism

- and discuss the controlled clinical evidence behind this approach.

Targeting behaviors

A multimodal approach is used to manage autistic disorder. Although behavioral techniques are useful and may decrease the need for drug therapy, one or more medications are often required to target severe maladaptive behaviors. Although we recommend that you consider all interfering behaviors when selecting medications, it is important to:

- initially focus on symptoms—such as self-injurious behaviors and aggression—that acutely affect the patient’s and caregiver’s safety

- consider the patient as being pre- or postpubertal, as developmental level may affect medication response.

Figure 1 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Aggression or self-injury. When drug therapy is needed to control severe aggression or self-injurious behavior, we recommend a trial of an atypical antipsychotic for prepubertal patients (Figure 1). Alternately, you may consider a mood stabilizer such as lithium or divalproex for an adult patient with prominent symptoms (Figure 2). However, mood stabilizer use requires monitoring by venipuncture for potential blood cell or liver function abnormalities.

Atypical antipsychotics are associated with adverse effects including sedation, weight gain, extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and hyperprolactinemia. Therefore, you may need to monitor weight, lipid profile, glucose, liver function, and cardiac function when using this class of agent.

Repetitive phenomena can be addressed with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although SSRIs may be activating in children and tend to be better tolerated in older adolescents and adults.

Anxiety. In children with anxiety, we suggest a trial of mirtazapine—because of its calming properties—before you try an SSRI. If both the SSRI and mirtazapine are ineffective, try an α2-adrenergic agonist. A baseline ECG is recommended before starting an α2-adrenergic agonist—particularly clonidine, which has been associated with rare cardiovascular events. Overall, these agents are well tolerated.

Hyperactivity, inattention. Anecdotal evidence indicates that stimulants may worsen symptoms of aggression, hyperactivity, and irritability in individuals with autism. Therefore, we suggest you start with an α2-adrenergic agonist when target symptoms include hyperactivity and inattention. Consider a stimulant trial if the α2-adrenergic agonist does not control the symptoms.

An atypical antipsychotic is generally recommended for autistic individuals with treatment-resistant hyperactivity and inattention, anxiety, and interfering repetitive behaviors.

Drug therapy. As summarized below, controlled evidence for behavior-based drug therapy of autism (Table.) suggests a role for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and psychostimulants in managing interfering behaviors.

Antipsychotics

Risperidone. Two controlled studies have reported the effect of risperidone on autism’s related symptoms.

McDougle et al conducted a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone, mean 2.9 mg/d, in adults with pervasive developmental disorders.2 Repetitive behavior, aggression, anxiety, irritability, depression, and general behavioral symptoms decreased in 8 of 14 patients, as measured by Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Sixteen subjects who received placebo showed no response. Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect.

More recently, the National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone, 0.5 to 3.5 mg/d (mean 1.8 mg/d), in 101 children and adolescents with autism.3 After 8 weeks, 69% of the risperidone group responded, compared with 12% of the placebo group. Response was defined as:

- at least a 25% decrease in the Irritability subscale score of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC)

- and CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”

Risperidone was effective for treating aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, and repetitive behavior. Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 2.7 kg vs. 0.8 kg with placebo), increased appetite, sedation, dizziness, and hypersalivation.

Olanzapine. A 12-week, open-label study of olanzapine, mean 7.8 mg/d, was conducted in eight patients ages 5 to 42 diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder.4 Hyperactivity, social relatedness, self-injurious behavior, aggression, anxiety, and depression improved significantly in six of seven patients who completed the trial, as measured by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 18.4 lbs) in six patients and sedation in three.

Malone et al conducted a 6-week, open-label comparison of olanzapine, mean 7.9 mg/d, versus haloperidol, mean 1.4 mg/d, in 12 children with autistic disorder.5 Five of six subjects who received olanzapine responded, compared with three of six who received haloperidol, as determined by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Anger/uncooperativeness and hyperactivity were reduced significantly only in the olanzapine group. Weight gain and sedation were the most common adverse effects with both medications. Weight gain was greater with olanzapine (mean 9 lbs) than with haloperidol (mean 3.2 lbs).

Quetiapine. Only one report addresses quetiapine in children and adolescents with autism.6 Two of six patients completed this 16-week, open-label trial of quetiapine, 100 to 350 mg/d (1.6 to 5.2 mg/kg/d). The group showed no statistically significant improvement in behavioral symptoms. Two patients achieved CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” One subject dropped out after a possible seizure during treatment, and three others withdrew because of sedation or lack of response.

Ziprasidone. McDougle et al conducted a naturalistic, open-label study of ziprasidone, 20 to 120 mg/d (mean 59.2 mg/d), in 12 subjects ages 8 to 20. Nine were diagnosed with autism and three with a pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). Six subjects responded across 14 weeks of treatment, as determined by ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI.7

Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect. Mean weight change was −5.83 lbs (range −35 to +6 lbs). Despite ziprasidone’s reported risk of causing abnormal cardiac rhythms, no cardiovascular adverse effects were reported.

Clozapine. Three case reports but no controlled studies have addressed clozapine in autistic disorder:

- Zuddas et al used clozapine, 100 to 200 mg/d for 3 months, to treat three children ages 8 to 12.8 Previous trials of haloperidol were ineffective, but the patients’ aggression, hyperactivity, negativism, and language and communication skills improved with clozapine, as measured by the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale (CPRS) and the Self-Injurious Behavior Questionnaire.

- Chen et al used clozapine, 275 mg/d, to treat a 17-year-old male inpatient.9 Aggression was significantly reduced across 15 days, as determined by a 21-question modified version of the CPRS. Side effects included mild constipation and excessive salivation.

- Clozapine, 300 mg/d for 2 months, reduced aggression in an adult patient and was associated with progressive and marked improvement of aggression and social interaction, as measured by the CGI and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). No agranulocytosis or extrapyramidal symptoms were observed across 5 years of therapy.10

Clozapine’s adverse effect profile probably explains why the literature contains so little data regarding its use in patients with autism. This drug’s propensity to lower the seizure threshold discourages its use in a population predisposed to seizures. Autistic patients also have a low tolerance for frequent venipuncture and limited ability to communicate agranulocytosis symptoms.

Antidepressants

Clomipramine—a tricyclic antidepressant with anti-obsessional properties—has shown some positive effects in treating autistic behaviors. Even so, this compound is prescribed infrequently to patients with autism because of low tolerability. In one recent double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study, 36 autistic patients ages 10 to 36 received:

- clomipramine, 100 to 150 mg/d (mean 128 mg/d)

- haloperidol, 1 to 1.5 mg/d (mean 1.3 mg/d)

or placebo for 7 weeks. Among patients who completed the trial, clomipramine and haloperidol were similarly effective in reducing overall autistic symptoms, irritability, and stereotypy. However, only 37.5% of those receiving clomipramine completed the study because of adverse effects, behavioral problems, and general lack of efficacy.11

Table

CONTROLLED EVIDENCE* FOR BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY OF AUTISM

| Medication | Behaviors improved | Significant adverse effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone 2 | Aggression, irritability | Mild transient sedation | Conducted in adults |

| Risperidone 3 | Aggression, irritability | Weight gain, increased appetite, sedation, tremor, hypersalivation | Largest controlled study to date in children with autism |

| Clomipramine 11 | Irritability, stereotypy | Tachycardia, tremors, diaphoresis, insomnia, nausea | Conducted in children and adults |

| Fluvoxamine 12 | Aggression, repetitive phenomena | Nausea, sedation | No published controlled pediatric data; unpublished pediatric data unfavorable |

| Clonidine 24 | Hyperactivity, irritability, stereotypies, oppositional behavior, aggression, self-injury | Hypotension, sedation, decreased activity | Small number of subjects |

| Clonidine 25 | Impulsivity, self-stimulation, hyperarousal | Sedation and fatigue | Small number of subjects |

| Methylphenidate 28 | Hyperactivity, irritability | Social withdrawal and irritability | Adverse effects more common at 0.6 mg/kg/dose |

| • Double-blind, placebo-controlled studies | |||

Fluvoxamine. Only one double-blind, placebo-controlled study has examined the use of an SSRI in autistic disorder.12 In this 12-week trial, 30 adults with autism received fluvoxamine, mean 276.7 mg/d, or placebo. Eight of 15 subjects in the fluvoxamine group were categorized as “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI.

Fluvoxamine was much more effective than placebo in reducing repetitive thoughts and behavior, aggression, and maladaptive behavior. Adverse effects included minimal sedation and nausea.

Unpublished data of McDougle et al suggest that autistic children and adolescents respond less favorably than adults to fluvoxamine. In a 12-week, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial in patients ages 5 to 18, only 1 of 18 subjects responded to fluvoxamine at a mean dosage of 106.9 mg/d. Agitation, increased aggression, hyperactivity, and increased repetitive behavior were reported.

Fluoxetine. Seven autistic patients ages 9 to 20 were treated with fluoxetine, 20 to 80 mg/d (mean 37.1 mg/d) in an 18-month longitudinal open trial. Irritability, lethargy, and stereotypy improved, as measured by the ABC.13 Adverse effects included increased hyperactivity and transient appetite suppression.

In another open-label trial of 37 autistic children ages 2 to 7, response was rated by investigators as “excellent” in 11 and “good” in another 11 who received fluoxetine, 0.2 to 1.4 mg/kg/d. However, aggression was a frequent cause for drug discontinuation during the 21-month study.14

Sertraline. In an open-label trial, Steingard et al treated nine autistic children ages 6 to 12 with sertraline, 25 to 50 mg/d for 2 to 8 weeks. Clinical improvement was observed in irritability, transition-associated anxiety, and need for sameness in eight of the children.15

Figure 2 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR POSTPUBERTAL PATIENTS WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc.In an open-label trial, 42 adults with pervasive developmental disorders were treated for 12 weeks with sertraline, 50 to 200 mg/d (mean 122 mg/d). Twenty-four (57%) achieved CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” in aggressive and repetitive behavior.16

Paroxetine. Fifteen adults with profound mental retardation (including seven with pervasive developmental disorders) received paroxetine, 10 to 50 mg/d (mean 35 mg/d) in a 4-month open-label trial. Frequency and severity of aggression were rated as improved after 1 month, but not at 4 months.17

Mirtazapine. In an open-label trial, 26 patients ages 3 to 23 with pervasive developmental disorders were treated with mirtazapine, 7.5 to 45 mg/d (mean 30.3 mg/d). Aggression, self-injury, irritability, hyperactivity, anxiety, depression, and insomnia decreased in 9 patients (34%), as determined by ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI. Adverse effects included increased appetite and transient sedation.18

Mood stabilizers

Lithium. No recent studies of lithium in pervasive developmental disorders are known to exist, but several case reports have been published:

- two reports found lithium decreased manic symptoms in individuals with autism and a family history of bipolar disorder19,20

- one report of lithium augmentation of fluvoxamine in an adult with autistic disorder noted markedly improved aggression and impulsivity after 2 weeks of treatment, as measured by the CGI, Brown Aggression Scale, and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale.21

Divalproex. In an open-label trial, 14 subjects ages 5 to 40 with pervasive developmental disorders were given divalproex sodium, 125 to 2,500 mg/d (mean 768 mg/d; mean blood level 75.8 mcg/mL. Affective instability, repetitive behavior, impulsivity, and aggression improved in 10 patients (71%), as measured by CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”22 Adverse effects included sedation, weight gain, hair loss, behavioral activation, and elevated liver enzymes.

Lamotrigine. In a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, lamotrigine, 5.0 mg/kg/d, was given to 14 children ages 3 to 11 with autistic disorder.23 Lamotrigine and placebo showed no significant differences in effect, as measured by the ABC, Autism Behavior Checklist, Vineland scales, Childhood Autism Rating Scale, and PreLinguistic Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale. Insomnia and hyperactivity were the most common adverse effects.

α2-adrenergic agonists

Clonidine. Jaselskis et al administered clonidine, 4 to 10 mcg/kg/d, to eight children ages 5 to 13 with autism in a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.24 Symptoms of hyperactivity, irritability, and oppositional behavior improved, as determined by teacher ratings on the ABC, Conners Abbreviated Parent-Teacher Questionnaire, and Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity Comprehensive Teacher’s Rating Scale. Adverse effects included hypotension, sedation, and decreased activity.

Nine autistic patients ages 5 to 33 received transdermal clonidine, 0.16 to 0.48 mcg/kg/d (mean 3.6 mcg/kg/d), in a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Hyperarousal, impulsivity, and self-stimulation improved, as measured by the Ritvo-Freeman Real Life Rating Scale and the CGI. Sedation and fatigue were reported, especially during the first 2 weeks of treatment.25

Guanfacine. The effect of guanfacine, 0.25 to 9.0 mg/d (mean 2.6 mg/d), was examined retrospectively in 80 children and adolescents ages 3 to 18 with pervasive developmental disorders.26 Hyperactivity, inattention, and tics improved in the 19 subjects (23.8%) who were rated “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI. Sedation was the most frequently reported adverse effect.

Psychostimulants

Early reports showed little benefit from stimulants in pervasive developmental disorders, but more recent studies suggest a modest effect. The RUPP Autism Network is conducting a large controlled investigation of methylphenidate to better understand the role of stimulants in children and adolescents in this diagnostic cluster.

Quintana et al conducted a double-blind, crossover study of methylphenidate, 10 or 20 mg bid for 2 weeks, in 10 children ages 7 to 11 with autism.27 Although irritability and hyperactivity showed statistically significant improvement as determined by the ABC and Conners Teacher Questionnaire, the authors reported only modest clinical effects. More recently, use of methylphenidate, 0.3 and 0.6 mg/kg/dose, was associated with a 50% decrease on the Connors Hyperactivity Index in 8 of 13 autistic children ages 5 to 11.28 Adverse effects—most common with the 0.6 mg/kg/dose—included social withdrawal and irritability in this double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.

Related resources

- McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, Charney DS, Leckman JF (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: Principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C (eds). Neuropsychopharmacology: the fifth generation of progress. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Autism booklet. www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/autism.cfm

- Autism Society of America. www.autism-society.org

Drug brand names

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Guanfacine • Tenex

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Stigler reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Posey receives grant support from and is a consultant to Eli Lilly & Co.

Dr. McDougle receives grant support from and is a consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly & Co., and Janssen Pharmaceutica, and is a speaker for Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Daniel X. Freedman Psychiatric Research Fellowship Award (Dr. Posey), a National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (Dr. Posey), a Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology contract (N01MH70001) from the National Institute of Mental Health to Indiana University (Drs. McDougle and Posey), a National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center grant to Indiana University (M01-RR00750), and a Department of Housing and Urban Development grant (B-01-SP-IN-0200).

Aggression, irritability, repetitive phenomena, or hyperactivity can interfere with the education and treatment of patients with autism.1 To assist clinicians in selecting drug therapies to control these behaviors, we developed a medication strategy based on controlled studies and our experience in an autism specialty clinic. In this article, we:

- offer an overview with two algorithms that show how to target maladaptive behaviors in patients of all ages with autism

- and discuss the controlled clinical evidence behind this approach.

Targeting behaviors

A multimodal approach is used to manage autistic disorder. Although behavioral techniques are useful and may decrease the need for drug therapy, one or more medications are often required to target severe maladaptive behaviors. Although we recommend that you consider all interfering behaviors when selecting medications, it is important to:

- initially focus on symptoms—such as self-injurious behaviors and aggression—that acutely affect the patient’s and caregiver’s safety

- consider the patient as being pre- or postpubertal, as developmental level may affect medication response.

Figure 1 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Aggression or self-injury. When drug therapy is needed to control severe aggression or self-injurious behavior, we recommend a trial of an atypical antipsychotic for prepubertal patients (Figure 1). Alternately, you may consider a mood stabilizer such as lithium or divalproex for an adult patient with prominent symptoms (Figure 2). However, mood stabilizer use requires monitoring by venipuncture for potential blood cell or liver function abnormalities.

Atypical antipsychotics are associated with adverse effects including sedation, weight gain, extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and hyperprolactinemia. Therefore, you may need to monitor weight, lipid profile, glucose, liver function, and cardiac function when using this class of agent.

Repetitive phenomena can be addressed with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although SSRIs may be activating in children and tend to be better tolerated in older adolescents and adults.

Anxiety. In children with anxiety, we suggest a trial of mirtazapine—because of its calming properties—before you try an SSRI. If both the SSRI and mirtazapine are ineffective, try an α2-adrenergic agonist. A baseline ECG is recommended before starting an α2-adrenergic agonist—particularly clonidine, which has been associated with rare cardiovascular events. Overall, these agents are well tolerated.

Hyperactivity, inattention. Anecdotal evidence indicates that stimulants may worsen symptoms of aggression, hyperactivity, and irritability in individuals with autism. Therefore, we suggest you start with an α2-adrenergic agonist when target symptoms include hyperactivity and inattention. Consider a stimulant trial if the α2-adrenergic agonist does not control the symptoms.

An atypical antipsychotic is generally recommended for autistic individuals with treatment-resistant hyperactivity and inattention, anxiety, and interfering repetitive behaviors.

Drug therapy. As summarized below, controlled evidence for behavior-based drug therapy of autism (Table.) suggests a role for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and psychostimulants in managing interfering behaviors.

Antipsychotics

Risperidone. Two controlled studies have reported the effect of risperidone on autism’s related symptoms.

McDougle et al conducted a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone, mean 2.9 mg/d, in adults with pervasive developmental disorders.2 Repetitive behavior, aggression, anxiety, irritability, depression, and general behavioral symptoms decreased in 8 of 14 patients, as measured by Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Sixteen subjects who received placebo showed no response. Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect.

More recently, the National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone, 0.5 to 3.5 mg/d (mean 1.8 mg/d), in 101 children and adolescents with autism.3 After 8 weeks, 69% of the risperidone group responded, compared with 12% of the placebo group. Response was defined as:

- at least a 25% decrease in the Irritability subscale score of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC)

- and CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”

Risperidone was effective for treating aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, and repetitive behavior. Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 2.7 kg vs. 0.8 kg with placebo), increased appetite, sedation, dizziness, and hypersalivation.

Olanzapine. A 12-week, open-label study of olanzapine, mean 7.8 mg/d, was conducted in eight patients ages 5 to 42 diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder.4 Hyperactivity, social relatedness, self-injurious behavior, aggression, anxiety, and depression improved significantly in six of seven patients who completed the trial, as measured by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 18.4 lbs) in six patients and sedation in three.

Malone et al conducted a 6-week, open-label comparison of olanzapine, mean 7.9 mg/d, versus haloperidol, mean 1.4 mg/d, in 12 children with autistic disorder.5 Five of six subjects who received olanzapine responded, compared with three of six who received haloperidol, as determined by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Anger/uncooperativeness and hyperactivity were reduced significantly only in the olanzapine group. Weight gain and sedation were the most common adverse effects with both medications. Weight gain was greater with olanzapine (mean 9 lbs) than with haloperidol (mean 3.2 lbs).

Quetiapine. Only one report addresses quetiapine in children and adolescents with autism.6 Two of six patients completed this 16-week, open-label trial of quetiapine, 100 to 350 mg/d (1.6 to 5.2 mg/kg/d). The group showed no statistically significant improvement in behavioral symptoms. Two patients achieved CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” One subject dropped out after a possible seizure during treatment, and three others withdrew because of sedation or lack of response.

Ziprasidone. McDougle et al conducted a naturalistic, open-label study of ziprasidone, 20 to 120 mg/d (mean 59.2 mg/d), in 12 subjects ages 8 to 20. Nine were diagnosed with autism and three with a pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). Six subjects responded across 14 weeks of treatment, as determined by ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI.7

Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect. Mean weight change was −5.83 lbs (range −35 to +6 lbs). Despite ziprasidone’s reported risk of causing abnormal cardiac rhythms, no cardiovascular adverse effects were reported.

Clozapine. Three case reports but no controlled studies have addressed clozapine in autistic disorder:

- Zuddas et al used clozapine, 100 to 200 mg/d for 3 months, to treat three children ages 8 to 12.8 Previous trials of haloperidol were ineffective, but the patients’ aggression, hyperactivity, negativism, and language and communication skills improved with clozapine, as measured by the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale (CPRS) and the Self-Injurious Behavior Questionnaire.

- Chen et al used clozapine, 275 mg/d, to treat a 17-year-old male inpatient.9 Aggression was significantly reduced across 15 days, as determined by a 21-question modified version of the CPRS. Side effects included mild constipation and excessive salivation.

- Clozapine, 300 mg/d for 2 months, reduced aggression in an adult patient and was associated with progressive and marked improvement of aggression and social interaction, as measured by the CGI and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). No agranulocytosis or extrapyramidal symptoms were observed across 5 years of therapy.10

Clozapine’s adverse effect profile probably explains why the literature contains so little data regarding its use in patients with autism. This drug’s propensity to lower the seizure threshold discourages its use in a population predisposed to seizures. Autistic patients also have a low tolerance for frequent venipuncture and limited ability to communicate agranulocytosis symptoms.

Antidepressants

Clomipramine—a tricyclic antidepressant with anti-obsessional properties—has shown some positive effects in treating autistic behaviors. Even so, this compound is prescribed infrequently to patients with autism because of low tolerability. In one recent double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study, 36 autistic patients ages 10 to 36 received:

- clomipramine, 100 to 150 mg/d (mean 128 mg/d)

- haloperidol, 1 to 1.5 mg/d (mean 1.3 mg/d)

or placebo for 7 weeks. Among patients who completed the trial, clomipramine and haloperidol were similarly effective in reducing overall autistic symptoms, irritability, and stereotypy. However, only 37.5% of those receiving clomipramine completed the study because of adverse effects, behavioral problems, and general lack of efficacy.11

Table

CONTROLLED EVIDENCE* FOR BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY OF AUTISM

| Medication | Behaviors improved | Significant adverse effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone 2 | Aggression, irritability | Mild transient sedation | Conducted in adults |

| Risperidone 3 | Aggression, irritability | Weight gain, increased appetite, sedation, tremor, hypersalivation | Largest controlled study to date in children with autism |

| Clomipramine 11 | Irritability, stereotypy | Tachycardia, tremors, diaphoresis, insomnia, nausea | Conducted in children and adults |

| Fluvoxamine 12 | Aggression, repetitive phenomena | Nausea, sedation | No published controlled pediatric data; unpublished pediatric data unfavorable |

| Clonidine 24 | Hyperactivity, irritability, stereotypies, oppositional behavior, aggression, self-injury | Hypotension, sedation, decreased activity | Small number of subjects |

| Clonidine 25 | Impulsivity, self-stimulation, hyperarousal | Sedation and fatigue | Small number of subjects |

| Methylphenidate 28 | Hyperactivity, irritability | Social withdrawal and irritability | Adverse effects more common at 0.6 mg/kg/dose |

| • Double-blind, placebo-controlled studies | |||

Fluvoxamine. Only one double-blind, placebo-controlled study has examined the use of an SSRI in autistic disorder.12 In this 12-week trial, 30 adults with autism received fluvoxamine, mean 276.7 mg/d, or placebo. Eight of 15 subjects in the fluvoxamine group were categorized as “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI.

Fluvoxamine was much more effective than placebo in reducing repetitive thoughts and behavior, aggression, and maladaptive behavior. Adverse effects included minimal sedation and nausea.

Unpublished data of McDougle et al suggest that autistic children and adolescents respond less favorably than adults to fluvoxamine. In a 12-week, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial in patients ages 5 to 18, only 1 of 18 subjects responded to fluvoxamine at a mean dosage of 106.9 mg/d. Agitation, increased aggression, hyperactivity, and increased repetitive behavior were reported.

Fluoxetine. Seven autistic patients ages 9 to 20 were treated with fluoxetine, 20 to 80 mg/d (mean 37.1 mg/d) in an 18-month longitudinal open trial. Irritability, lethargy, and stereotypy improved, as measured by the ABC.13 Adverse effects included increased hyperactivity and transient appetite suppression.

In another open-label trial of 37 autistic children ages 2 to 7, response was rated by investigators as “excellent” in 11 and “good” in another 11 who received fluoxetine, 0.2 to 1.4 mg/kg/d. However, aggression was a frequent cause for drug discontinuation during the 21-month study.14

Sertraline. In an open-label trial, Steingard et al treated nine autistic children ages 6 to 12 with sertraline, 25 to 50 mg/d for 2 to 8 weeks. Clinical improvement was observed in irritability, transition-associated anxiety, and need for sameness in eight of the children.15

Figure 2 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR POSTPUBERTAL PATIENTS WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc.In an open-label trial, 42 adults with pervasive developmental disorders were treated for 12 weeks with sertraline, 50 to 200 mg/d (mean 122 mg/d). Twenty-four (57%) achieved CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” in aggressive and repetitive behavior.16

Paroxetine. Fifteen adults with profound mental retardation (including seven with pervasive developmental disorders) received paroxetine, 10 to 50 mg/d (mean 35 mg/d) in a 4-month open-label trial. Frequency and severity of aggression were rated as improved after 1 month, but not at 4 months.17

Mirtazapine. In an open-label trial, 26 patients ages 3 to 23 with pervasive developmental disorders were treated with mirtazapine, 7.5 to 45 mg/d (mean 30.3 mg/d). Aggression, self-injury, irritability, hyperactivity, anxiety, depression, and insomnia decreased in 9 patients (34%), as determined by ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI. Adverse effects included increased appetite and transient sedation.18

Mood stabilizers

Lithium. No recent studies of lithium in pervasive developmental disorders are known to exist, but several case reports have been published:

- two reports found lithium decreased manic symptoms in individuals with autism and a family history of bipolar disorder19,20

- one report of lithium augmentation of fluvoxamine in an adult with autistic disorder noted markedly improved aggression and impulsivity after 2 weeks of treatment, as measured by the CGI, Brown Aggression Scale, and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale.21

Divalproex. In an open-label trial, 14 subjects ages 5 to 40 with pervasive developmental disorders were given divalproex sodium, 125 to 2,500 mg/d (mean 768 mg/d; mean blood level 75.8 mcg/mL. Affective instability, repetitive behavior, impulsivity, and aggression improved in 10 patients (71%), as measured by CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”22 Adverse effects included sedation, weight gain, hair loss, behavioral activation, and elevated liver enzymes.

Lamotrigine. In a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, lamotrigine, 5.0 mg/kg/d, was given to 14 children ages 3 to 11 with autistic disorder.23 Lamotrigine and placebo showed no significant differences in effect, as measured by the ABC, Autism Behavior Checklist, Vineland scales, Childhood Autism Rating Scale, and PreLinguistic Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale. Insomnia and hyperactivity were the most common adverse effects.

α2-adrenergic agonists

Clonidine. Jaselskis et al administered clonidine, 4 to 10 mcg/kg/d, to eight children ages 5 to 13 with autism in a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.24 Symptoms of hyperactivity, irritability, and oppositional behavior improved, as determined by teacher ratings on the ABC, Conners Abbreviated Parent-Teacher Questionnaire, and Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity Comprehensive Teacher’s Rating Scale. Adverse effects included hypotension, sedation, and decreased activity.

Nine autistic patients ages 5 to 33 received transdermal clonidine, 0.16 to 0.48 mcg/kg/d (mean 3.6 mcg/kg/d), in a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Hyperarousal, impulsivity, and self-stimulation improved, as measured by the Ritvo-Freeman Real Life Rating Scale and the CGI. Sedation and fatigue were reported, especially during the first 2 weeks of treatment.25

Guanfacine. The effect of guanfacine, 0.25 to 9.0 mg/d (mean 2.6 mg/d), was examined retrospectively in 80 children and adolescents ages 3 to 18 with pervasive developmental disorders.26 Hyperactivity, inattention, and tics improved in the 19 subjects (23.8%) who were rated “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI. Sedation was the most frequently reported adverse effect.

Psychostimulants

Early reports showed little benefit from stimulants in pervasive developmental disorders, but more recent studies suggest a modest effect. The RUPP Autism Network is conducting a large controlled investigation of methylphenidate to better understand the role of stimulants in children and adolescents in this diagnostic cluster.

Quintana et al conducted a double-blind, crossover study of methylphenidate, 10 or 20 mg bid for 2 weeks, in 10 children ages 7 to 11 with autism.27 Although irritability and hyperactivity showed statistically significant improvement as determined by the ABC and Conners Teacher Questionnaire, the authors reported only modest clinical effects. More recently, use of methylphenidate, 0.3 and 0.6 mg/kg/dose, was associated with a 50% decrease on the Connors Hyperactivity Index in 8 of 13 autistic children ages 5 to 11.28 Adverse effects—most common with the 0.6 mg/kg/dose—included social withdrawal and irritability in this double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.

Related resources

- McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, Charney DS, Leckman JF (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: Principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C (eds). Neuropsychopharmacology: the fifth generation of progress. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Autism booklet. www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/autism.cfm

- Autism Society of America. www.autism-society.org

Drug brand names

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Guanfacine • Tenex

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Stigler reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Posey receives grant support from and is a consultant to Eli Lilly & Co.

Dr. McDougle receives grant support from and is a consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly & Co., and Janssen Pharmaceutica, and is a speaker for Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Daniel X. Freedman Psychiatric Research Fellowship Award (Dr. Posey), a National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (Dr. Posey), a Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology contract (N01MH70001) from the National Institute of Mental Health to Indiana University (Drs. McDougle and Posey), a National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center grant to Indiana University (M01-RR00750), and a Department of Housing and Urban Development grant (B-01-SP-IN-0200).

1. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

2. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, Pelton GH, Cohen DJ, Price LH. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:633-41.

3. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 2002;347(5):314-21.

4. Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, McDougle CJ. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: An open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999;19:37-44.

5. Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, Choudhury MS, Delaney MA. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(8):887-94.

6. Martin A, Koenig K, Scahill L, Bregman J. Open-label quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999;9:99-107.

7. McDougle CJ, Kem DL, Posey DJ. Case series: use of ziprasidone for maladaptive symptoms in youths with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41(8):921-7.

8. Zuddas A, Ledda MG, Fratta A, Muglia P, Cianchetti C. Clinical effects of clozapine on autistic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153(5):738.-

9. Chen NC, Bedair HS, McKay B, Bowers MB, Mazure C. Clozapine in the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(6):479-80.

10. Gobbi G, Pulvirenti L. Long-term treatment with clozapine in an adult with autistic disorder accompanied by aggressive behaviour. J Psych Neurol 2001;26(4):340-1.

11. Remington G, Sloman L, Konstantareas M, Parker K, Gow R. Clomipramine versus haloperidol in the treatment of autistic disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21(4):440-4.

12. McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, Heninger GR, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:1001-8.

13. Fatemi SH, Realmuto GM, Khan L, Thuras P. Fluoxetine in treatment of adolescent patients with autism: a longitudinal open trial. J Autism Dev Disord 1998;28(4):303-7.

14. DeLong GR, Teague LA, Kamran MM. Effects of fluoxetine treatment in young children with idiopathic autism. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:551-62.

15. Steingard RJ, Zimnitzky B, DeMaso DR, Bauman ML, Bucci JP. Sertraline treatment of transition-associated anxiety and agitation in children with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997;7(1):9-15.

16. McDougle CJ, Brodkin ES, Naylor ST, Carlson DC, Cohen DJ, Price LH. Sertraline in adults with pervasive developmental disorders: a prospective open-label investigation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18:62-6.

17. Davanzo PA, Belin TR, Widawski MH, King BH. Paroxetine treatment of aggression and self-injury in persons with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 1998;102(5):427-37.

18. Posey DJ, Guenin KD, Kohn AE, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. A naturalistic open-label study of mirtazapine in autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001;11(3):267-77.

19. Kerbeshian J, Burd L, Fisher W. Lithium carbonate in the treatment of two patients with infantile autism and atypical bipolar symptomatology. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987;7(6):401-5.

20. Steingard R, Biederman J. Lithium-responsive manic-like symptoms in two individuals with autism and mental retardation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987;26:932-5.

21. Epperson CN, McDougle CJ, Anand A, et al. Lithium augmentation of fluvoxamine in autistic disorder: a case report. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1994;4:201-7.

22. Hollander E, Dolgoff-Kaspar R, Cartwright C, Rawitt R, Novotny S. An open trial of divalproex sodium in autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(7):530-4.

23. Belsito KM, Law PA, Kirk KS, Landa RJ, Zimmerman AW. Lamotrigine therapy for autistic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31(2):175-81.

24. Jaselskis CA, Cook EH, Fletcher KE, Leventhal BL. Clonidine treatment of hyperactive and impulsive children with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12(5):322-7.

25. Fankhauser MP, Karumanchi VC, German ML, Yates A, Karumanchi SD. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of transdermal clonidine in autism. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53(3):77-82.

26. Posey DJ, Decker J, Sasher TM, Kohburn A, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. A retrospective analysis of guanfacine in the treatment of autism. New Orleans: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2001; new research abstracts no. 816.

27. Quintana H, Birmaher B, Stedge D, et al. Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 1995;25(3):283-95.

28. Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M. Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2000;30(3):245-55.

1. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

2. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, Pelton GH, Cohen DJ, Price LH. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:633-41.

3. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 2002;347(5):314-21.

4. Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, McDougle CJ. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: An open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999;19:37-44.

5. Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, Choudhury MS, Delaney MA. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(8):887-94.

6. Martin A, Koenig K, Scahill L, Bregman J. Open-label quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999;9:99-107.

7. McDougle CJ, Kem DL, Posey DJ. Case series: use of ziprasidone for maladaptive symptoms in youths with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41(8):921-7.

8. Zuddas A, Ledda MG, Fratta A, Muglia P, Cianchetti C. Clinical effects of clozapine on autistic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153(5):738.-

9. Chen NC, Bedair HS, McKay B, Bowers MB, Mazure C. Clozapine in the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(6):479-80.

10. Gobbi G, Pulvirenti L. Long-term treatment with clozapine in an adult with autistic disorder accompanied by aggressive behaviour. J Psych Neurol 2001;26(4):340-1.

11. Remington G, Sloman L, Konstantareas M, Parker K, Gow R. Clomipramine versus haloperidol in the treatment of autistic disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21(4):440-4.

12. McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, Heninger GR, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:1001-8.

13. Fatemi SH, Realmuto GM, Khan L, Thuras P. Fluoxetine in treatment of adolescent patients with autism: a longitudinal open trial. J Autism Dev Disord 1998;28(4):303-7.

14. DeLong GR, Teague LA, Kamran MM. Effects of fluoxetine treatment in young children with idiopathic autism. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:551-62.

15. Steingard RJ, Zimnitzky B, DeMaso DR, Bauman ML, Bucci JP. Sertraline treatment of transition-associated anxiety and agitation in children with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997;7(1):9-15.

16. McDougle CJ, Brodkin ES, Naylor ST, Carlson DC, Cohen DJ, Price LH. Sertraline in adults with pervasive developmental disorders: a prospective open-label investigation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18:62-6.

17. Davanzo PA, Belin TR, Widawski MH, King BH. Paroxetine treatment of aggression and self-injury in persons with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 1998;102(5):427-37.

18. Posey DJ, Guenin KD, Kohn AE, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. A naturalistic open-label study of mirtazapine in autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001;11(3):267-77.

19. Kerbeshian J, Burd L, Fisher W. Lithium carbonate in the treatment of two patients with infantile autism and atypical bipolar symptomatology. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987;7(6):401-5.

20. Steingard R, Biederman J. Lithium-responsive manic-like symptoms in two individuals with autism and mental retardation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987;26:932-5.

21. Epperson CN, McDougle CJ, Anand A, et al. Lithium augmentation of fluvoxamine in autistic disorder: a case report. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1994;4:201-7.

22. Hollander E, Dolgoff-Kaspar R, Cartwright C, Rawitt R, Novotny S. An open trial of divalproex sodium in autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(7):530-4.

23. Belsito KM, Law PA, Kirk KS, Landa RJ, Zimmerman AW. Lamotrigine therapy for autistic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31(2):175-81.

24. Jaselskis CA, Cook EH, Fletcher KE, Leventhal BL. Clonidine treatment of hyperactive and impulsive children with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12(5):322-7.

25. Fankhauser MP, Karumanchi VC, German ML, Yates A, Karumanchi SD. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of transdermal clonidine in autism. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53(3):77-82.

26. Posey DJ, Decker J, Sasher TM, Kohburn A, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. A retrospective analysis of guanfacine in the treatment of autism. New Orleans: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2001; new research abstracts no. 816.

27. Quintana H, Birmaher B, Stedge D, et al. Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 1995;25(3):283-95.

28. Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M. Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2000;30(3):245-55.