User login

While nationwide demand for hospitalists outstrips supply, hospitals across the country are looking at how their hospitalists and their hospital medicine groups weigh in on efficiency.

The notion of efficiency at a time of rapid growth may seem counterintuitive, but healthcare dollars are always hotly contested, and an efficient hospitalist program has a better chance of capturing them than a less-efficient one.

Even the definition of efficiency is being refined. Stakeholders scrutinizing compensation packages, key clinical indicators, productivity and quality metrics, scheduling, average daily census, and patient handoffs to gauge whether or not their group has a competitive edge over others. And hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders are scrutinizing themselves because they know hospitals increasingly are inviting more than one HMG to work under their roofs—the better to serve different populations and compare one with another.

How to Measure Efficiency

An evolving medical discipline that aspires to specialize in internal medicine, hospital medicine is in the process of developing a consensus definition of efficiency for itself. Major variables included in the calculation are obvious: average daily census, length of stay (LOS), case mix-adjusted costs, severity, and readmission rates. Other, harder-to-quantify dimensions include how a hospitalist group practice affects mortality, and how scheduling, variable costs, hospitalist group type, subsidies, and level of expertise play out.

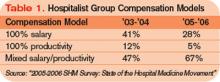

The foundation on which hospitalist groups build their efficiencies is the group type. In itself, how a hospitalist group chooses to organize itself reflects a maturing marketplace. SHM’s 2005-2006 productivity survey shows an increase in multistate hospitalist groups, up from 9% in ’03-’04 to 19% in the latest survey. Local private hospitalist groups fell from 20% in ’03-’04 to 12% in ’05-’06. The percentage of academic hospitalist groups rose from 16% to 20% in the same period.

It’s unclear how to interpret the shift from local to multistate hospitalist groups and the increase in academic medical center programs, but these trends bear watching. Comparison of the two most recent SHM surveys shows compensation models are also growing up, reflecting the need to balance base salary with productivity.

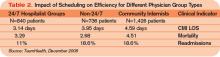

A major indicator of hospital group efficiency is the performance of groups with hospitalists on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although hospital administrators and hospitalist leaders struggle with the economics of providing night coverage when admissions are slow, such coverage pays off in quality and efficiency.

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a healthcare outsourcing firm based in Knoxville, Tenn., has long advocated 24/7 coverage as a crucial element in HMG efficiency. Even though she estimates that night coverage adds approximately $10,000 in subsidies to an average compensation package for a full-time hospitalist, such coverage improves efficiency in length of stay adjusted for severity and in readmissions. Full coverage allows hospitalists to be better integrated into the hospital in a way that fewer hours don’t.

“How hospitalists who cover 24/7 are used varies,” says Dr. Goldsholl. “Doing night admissions for community doctors, [working] as intensivist extenders, helping with ED [emergency department] throughput, being on rapid response teams—all are important contributors to improved efficiency,” says Dr. Goldsholl.

For Dr. Goldsholl, who has at least one academic medical center—Good Samaritan in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine—on her roster, hospitalist group efficiency and productivity are major concerns for academic and community hospital administrators footing the bill for such services.

“Usually, TeamHealth is the exclusive hospitalist medicine provider contracting with a community hospital,” she explains. “Once we have been in a hospital for a while, we tend to see a progression in our responsibilities. Mostly we start with unassigned patients, then we expand to cover private primary care physicians’ patients. Then we co-manage complex cases with sub-specialists.”

Despite operating mostly in community hospitals, Dr. Goldsholl has fielded more queries from academic medical centers (AMCs) in the past several years.

“We’re definitely getting more interest from AMCs,” Dr. Goldsholl notes. “The work-hours restriction on residents—faculty who are uninterested in being hospitalists—whatever is driving their interest, they’re looking for solutions for handling their unassigned patients and beyond. To outsource to a private hospitalist company, an academic medical center would have to be in some pain, but interest is definitely picking up.”

Cogent Healthcare’s June 2006 contract with Temple University Hospital (TUH), Philadelphia, to provide a 24/7 hospitalist program of teaching and non-teaching services is another example of hospitals striving for efficiency. To better reach its clinical, economic, and regulatory goals, TUH switched from its own academic hospitalist group to partner with Cogent to manage its adult medical/surgical population. It’s too soon to gauge the results.

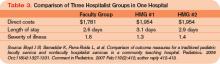

Despite stakeholders’ need to know more about which hospitalist group structure is most efficient, there’s little published data on AMC versus private group efficiency. One important study, published in the American Journal of Medicine (AJM) in May 2005, compared an academic hospitalist group with a private hospitalist group and community internists on several efficiency measures. The academic hospitalists’ patients had a 13% shorter LOS than those patients cared for by other groups and academic hospitalists had lowered costs by $173 per case, versus $109 for the private hospitalist group. The academic hospitalists also had a 20% relative risk reduction for severity of illness over the community physicians.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, the AJM study’s lead author and chair of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee for SHM, speculated that the academic hospitalist groups’ efficiency resulted from fewer handoffs and that academic hospitalists’ relationships with their hospitals were more aligned than those of outsiders, both from financial and quality perspectives. Additionally, the academic hospitalist group used the hospital’s computerized physician order entry system and followed its protocols for clinical pathways and core measures. Scheduling also made a difference. The academic group worked in half-month blocks for an average of 14 weeks, while the private hospitalists worked from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and some nights and weekends, leaving moonlighters to cover 75% of nights, weekends, and holidays and providing for rockier handoffs.

Another study comparing a traditional pediatric faculty group with two private hospitalist groups at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center of Phoenix showed that the faculty group outperformed the private hospitalists on all measures.

The authors concluded that faculty models can be as efficient as or more efficient than private groups in terms of direct costs and LOS.

Fine Tuning

Although academic hospitalist groups have been thought of as less efficient than private hospitalist groups because the former tend to use salaried employees while the latter tend to compensate employees based more on performance, the data cited above indicate academic hospitalist groups may have a competitive edge with regard to efficiency. What may account for the difference is that academic hospitalists are familiar with and often products of their hospital’s culture and mores. Unlike physicians working for private hospitalist groups with their own structure and culture, academic hospitalists are of a piece with their hospital. It’s common to find academic hospitalists who return to their medical school alma mater after a stint in an office-based practice. Some never left, joining the academic hospitalist group directly from residency.

For the chief of a hospitalist program, being so attuned to the hospital’s rhythms can be a mixed blessing.

Pat Cawley, MD, is the hospitalist program director and founder of the academic hospitalist group at the Charleston-based Medical University of South Carolina’s Hospital. He has a hard time focusing on hospitalist group efficiency, though, when he’s still flat-out recruiting.

“Demand for hospitalists is still way outstripping supply,” says Dr. Cawley. “We currently have nine hospitalists and plan to add five more this year, but we could actually use 10 more.”

The South Carolina market is competitive, with other hospitals planning to establish hospitalist medicine programs and vying with Dr. Cawley’s program for fresh physicians. Medical University Hospital’s hospitalist group started in July 2003 with four physicians and has kept growing. The hospitalists spend most of their time functioning as a teaching service and also cover a long-term acute-care facility at another hospital.

Defining efficiency in South Carolina’s booming market is secondary to recruiting and incorporating new physicians as team members. Dr. Cawley uses average daily census (ADC) as an efficiency benchmark: 15-20 patients per hospitalist is productive, although many doctors are comfortable at 12.

“We looked at our learning curve, about 10-12,” points out Dr. Cawley. “We think 15-20 is better, although some places are reporting an ADC of 22. But after a certain point, performance doesn’t appear to improve.”

A big problem with improving hospitalist group efficiency, according to Dr. Cawley, is hospital inefficiency: “Lack of IT to get lab results quickly, not enough nursing and secretarial support for admissions and discharges, policies on contacting the primary doc versus having a standing order for a procedure—all decrease efficiency.”

He’d also like his hospital administrators to allow nurses to pronounce death (common in community hospitals but less so in AMCs). “The power of hospitalists is to challenge the hospital’s inefficiencies, to break down the barriers to more efficient practices,” adds Dr. Cawley. “Many institutions need huge culture change, and hospitalists must lead the way.”

A close watcher of hospitalist performance, Scott Oxenhandler, MD, medical director of the Memorial Hospitalist Group in Hollywood, Fla., heads a hospitalist group he started in June 2004 that now has 23 physicians and two nurse practitioners. Memorial Hospital also has two other private hospitalist groups. While Dr. Oxenhandler’s group handles unassigned patients (55%) and Medicaid/Medicare patients (45%), the other hospitalist groups have captured the more lucrative business of managed care and other commercially insured patients.

—Per Danielsson, MD, medical director, Swedish Medical Center Adult Hospitalist Program, Seattle

Dr. Oxenhandler says efficiency is a complicated issue involving several key components. “Following evidence-based medicine protocols and CMS core measures are fairly straightforward [ideas] for all of us,” he says, “but financial measures are more complex.”

He has taken aim at adjusted variable costs per discharge on lab tests, pharmacy, and radiology, “three areas where I know that our group can improve,” he adds.

As for how hard and how efficiently a hospitalist works, Dr. Oxenhandler is taking a closer look at that as his group and the field mature. “We know that average daily census can be deceiving and RVUs [relative value units] are more relevant to efficiency but not perfect,” he says. “Another factor is tenure with the hospitalist group. For the physician to excel and to mature clinically, he or she needs to stay with a hospitalist group long enough to improve readmission rates and to get a sense of how to better manage clinical resources.’’

Dr. Oxenhandler describes a patient presenting with heart failure and anemia to show how a hospitalist’s clinical skills might mature. After several days of repeated hemoglobin studies indicating anemia, the hospitalist might refer the patient—once stabilized and discharged—to his primary physician for an outpatient work-up for possible colon cancer—rather than do so during the hospitalization.

Dr. Oxenhandler has contemplated pursuing managed care contracts but hesitates because his hospitalist group’s clinical and cost performance is equal to that of the hospitalist group that currently holds such contracts. “Why should they switch to us unless we can outperform the other group?” he muses. “Plus, there would be added cost for us in more paperwork and administration, and we’d have to improve our efficiency to make it worthwhile.”

Per Danielsson, MD, Swedish Medical Center’s Adult Hospitalist Program’s medical director, has hospitalists rotating among the First Hill, Cherry Hill, and Ballard campuses in Seattle, Wash. Demand for hospitalist services at the sites keeps growing, and Dr. Danielsson sees no end in sight. “Today’s hospital stays are getting shorter, and the patients are sicker, and there is increasing pressure for greater efficiency here,” he says.

Overall, clinicians, administrators, and researchers need to zero in on the organizational factors of hospitalist groups—from scheduling to 24/7 coverage, handoffs, and use of in-hospital resources—to improve efficiency. At present, academic hospitalist groups appear to have a slight edge because they’re tied more closely to hospital personnel, technology, and care pathways than private groups that come from outside the hospital. But there isn’t enough data either way to say which group type is the most efficient. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

While nationwide demand for hospitalists outstrips supply, hospitals across the country are looking at how their hospitalists and their hospital medicine groups weigh in on efficiency.

The notion of efficiency at a time of rapid growth may seem counterintuitive, but healthcare dollars are always hotly contested, and an efficient hospitalist program has a better chance of capturing them than a less-efficient one.

Even the definition of efficiency is being refined. Stakeholders scrutinizing compensation packages, key clinical indicators, productivity and quality metrics, scheduling, average daily census, and patient handoffs to gauge whether or not their group has a competitive edge over others. And hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders are scrutinizing themselves because they know hospitals increasingly are inviting more than one HMG to work under their roofs—the better to serve different populations and compare one with another.

How to Measure Efficiency

An evolving medical discipline that aspires to specialize in internal medicine, hospital medicine is in the process of developing a consensus definition of efficiency for itself. Major variables included in the calculation are obvious: average daily census, length of stay (LOS), case mix-adjusted costs, severity, and readmission rates. Other, harder-to-quantify dimensions include how a hospitalist group practice affects mortality, and how scheduling, variable costs, hospitalist group type, subsidies, and level of expertise play out.

The foundation on which hospitalist groups build their efficiencies is the group type. In itself, how a hospitalist group chooses to organize itself reflects a maturing marketplace. SHM’s 2005-2006 productivity survey shows an increase in multistate hospitalist groups, up from 9% in ’03-’04 to 19% in the latest survey. Local private hospitalist groups fell from 20% in ’03-’04 to 12% in ’05-’06. The percentage of academic hospitalist groups rose from 16% to 20% in the same period.

It’s unclear how to interpret the shift from local to multistate hospitalist groups and the increase in academic medical center programs, but these trends bear watching. Comparison of the two most recent SHM surveys shows compensation models are also growing up, reflecting the need to balance base salary with productivity.

A major indicator of hospital group efficiency is the performance of groups with hospitalists on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although hospital administrators and hospitalist leaders struggle with the economics of providing night coverage when admissions are slow, such coverage pays off in quality and efficiency.

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a healthcare outsourcing firm based in Knoxville, Tenn., has long advocated 24/7 coverage as a crucial element in HMG efficiency. Even though she estimates that night coverage adds approximately $10,000 in subsidies to an average compensation package for a full-time hospitalist, such coverage improves efficiency in length of stay adjusted for severity and in readmissions. Full coverage allows hospitalists to be better integrated into the hospital in a way that fewer hours don’t.

“How hospitalists who cover 24/7 are used varies,” says Dr. Goldsholl. “Doing night admissions for community doctors, [working] as intensivist extenders, helping with ED [emergency department] throughput, being on rapid response teams—all are important contributors to improved efficiency,” says Dr. Goldsholl.

For Dr. Goldsholl, who has at least one academic medical center—Good Samaritan in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine—on her roster, hospitalist group efficiency and productivity are major concerns for academic and community hospital administrators footing the bill for such services.

“Usually, TeamHealth is the exclusive hospitalist medicine provider contracting with a community hospital,” she explains. “Once we have been in a hospital for a while, we tend to see a progression in our responsibilities. Mostly we start with unassigned patients, then we expand to cover private primary care physicians’ patients. Then we co-manage complex cases with sub-specialists.”

Despite operating mostly in community hospitals, Dr. Goldsholl has fielded more queries from academic medical centers (AMCs) in the past several years.

“We’re definitely getting more interest from AMCs,” Dr. Goldsholl notes. “The work-hours restriction on residents—faculty who are uninterested in being hospitalists—whatever is driving their interest, they’re looking for solutions for handling their unassigned patients and beyond. To outsource to a private hospitalist company, an academic medical center would have to be in some pain, but interest is definitely picking up.”

Cogent Healthcare’s June 2006 contract with Temple University Hospital (TUH), Philadelphia, to provide a 24/7 hospitalist program of teaching and non-teaching services is another example of hospitals striving for efficiency. To better reach its clinical, economic, and regulatory goals, TUH switched from its own academic hospitalist group to partner with Cogent to manage its adult medical/surgical population. It’s too soon to gauge the results.

Despite stakeholders’ need to know more about which hospitalist group structure is most efficient, there’s little published data on AMC versus private group efficiency. One important study, published in the American Journal of Medicine (AJM) in May 2005, compared an academic hospitalist group with a private hospitalist group and community internists on several efficiency measures. The academic hospitalists’ patients had a 13% shorter LOS than those patients cared for by other groups and academic hospitalists had lowered costs by $173 per case, versus $109 for the private hospitalist group. The academic hospitalists also had a 20% relative risk reduction for severity of illness over the community physicians.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, the AJM study’s lead author and chair of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee for SHM, speculated that the academic hospitalist groups’ efficiency resulted from fewer handoffs and that academic hospitalists’ relationships with their hospitals were more aligned than those of outsiders, both from financial and quality perspectives. Additionally, the academic hospitalist group used the hospital’s computerized physician order entry system and followed its protocols for clinical pathways and core measures. Scheduling also made a difference. The academic group worked in half-month blocks for an average of 14 weeks, while the private hospitalists worked from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and some nights and weekends, leaving moonlighters to cover 75% of nights, weekends, and holidays and providing for rockier handoffs.

Another study comparing a traditional pediatric faculty group with two private hospitalist groups at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center of Phoenix showed that the faculty group outperformed the private hospitalists on all measures.

The authors concluded that faculty models can be as efficient as or more efficient than private groups in terms of direct costs and LOS.

Fine Tuning

Although academic hospitalist groups have been thought of as less efficient than private hospitalist groups because the former tend to use salaried employees while the latter tend to compensate employees based more on performance, the data cited above indicate academic hospitalist groups may have a competitive edge with regard to efficiency. What may account for the difference is that academic hospitalists are familiar with and often products of their hospital’s culture and mores. Unlike physicians working for private hospitalist groups with their own structure and culture, academic hospitalists are of a piece with their hospital. It’s common to find academic hospitalists who return to their medical school alma mater after a stint in an office-based practice. Some never left, joining the academic hospitalist group directly from residency.

For the chief of a hospitalist program, being so attuned to the hospital’s rhythms can be a mixed blessing.

Pat Cawley, MD, is the hospitalist program director and founder of the academic hospitalist group at the Charleston-based Medical University of South Carolina’s Hospital. He has a hard time focusing on hospitalist group efficiency, though, when he’s still flat-out recruiting.

“Demand for hospitalists is still way outstripping supply,” says Dr. Cawley. “We currently have nine hospitalists and plan to add five more this year, but we could actually use 10 more.”

The South Carolina market is competitive, with other hospitals planning to establish hospitalist medicine programs and vying with Dr. Cawley’s program for fresh physicians. Medical University Hospital’s hospitalist group started in July 2003 with four physicians and has kept growing. The hospitalists spend most of their time functioning as a teaching service and also cover a long-term acute-care facility at another hospital.

Defining efficiency in South Carolina’s booming market is secondary to recruiting and incorporating new physicians as team members. Dr. Cawley uses average daily census (ADC) as an efficiency benchmark: 15-20 patients per hospitalist is productive, although many doctors are comfortable at 12.

“We looked at our learning curve, about 10-12,” points out Dr. Cawley. “We think 15-20 is better, although some places are reporting an ADC of 22. But after a certain point, performance doesn’t appear to improve.”

A big problem with improving hospitalist group efficiency, according to Dr. Cawley, is hospital inefficiency: “Lack of IT to get lab results quickly, not enough nursing and secretarial support for admissions and discharges, policies on contacting the primary doc versus having a standing order for a procedure—all decrease efficiency.”

He’d also like his hospital administrators to allow nurses to pronounce death (common in community hospitals but less so in AMCs). “The power of hospitalists is to challenge the hospital’s inefficiencies, to break down the barriers to more efficient practices,” adds Dr. Cawley. “Many institutions need huge culture change, and hospitalists must lead the way.”

A close watcher of hospitalist performance, Scott Oxenhandler, MD, medical director of the Memorial Hospitalist Group in Hollywood, Fla., heads a hospitalist group he started in June 2004 that now has 23 physicians and two nurse practitioners. Memorial Hospital also has two other private hospitalist groups. While Dr. Oxenhandler’s group handles unassigned patients (55%) and Medicaid/Medicare patients (45%), the other hospitalist groups have captured the more lucrative business of managed care and other commercially insured patients.

—Per Danielsson, MD, medical director, Swedish Medical Center Adult Hospitalist Program, Seattle

Dr. Oxenhandler says efficiency is a complicated issue involving several key components. “Following evidence-based medicine protocols and CMS core measures are fairly straightforward [ideas] for all of us,” he says, “but financial measures are more complex.”

He has taken aim at adjusted variable costs per discharge on lab tests, pharmacy, and radiology, “three areas where I know that our group can improve,” he adds.

As for how hard and how efficiently a hospitalist works, Dr. Oxenhandler is taking a closer look at that as his group and the field mature. “We know that average daily census can be deceiving and RVUs [relative value units] are more relevant to efficiency but not perfect,” he says. “Another factor is tenure with the hospitalist group. For the physician to excel and to mature clinically, he or she needs to stay with a hospitalist group long enough to improve readmission rates and to get a sense of how to better manage clinical resources.’’

Dr. Oxenhandler describes a patient presenting with heart failure and anemia to show how a hospitalist’s clinical skills might mature. After several days of repeated hemoglobin studies indicating anemia, the hospitalist might refer the patient—once stabilized and discharged—to his primary physician for an outpatient work-up for possible colon cancer—rather than do so during the hospitalization.

Dr. Oxenhandler has contemplated pursuing managed care contracts but hesitates because his hospitalist group’s clinical and cost performance is equal to that of the hospitalist group that currently holds such contracts. “Why should they switch to us unless we can outperform the other group?” he muses. “Plus, there would be added cost for us in more paperwork and administration, and we’d have to improve our efficiency to make it worthwhile.”

Per Danielsson, MD, Swedish Medical Center’s Adult Hospitalist Program’s medical director, has hospitalists rotating among the First Hill, Cherry Hill, and Ballard campuses in Seattle, Wash. Demand for hospitalist services at the sites keeps growing, and Dr. Danielsson sees no end in sight. “Today’s hospital stays are getting shorter, and the patients are sicker, and there is increasing pressure for greater efficiency here,” he says.

Overall, clinicians, administrators, and researchers need to zero in on the organizational factors of hospitalist groups—from scheduling to 24/7 coverage, handoffs, and use of in-hospital resources—to improve efficiency. At present, academic hospitalist groups appear to have a slight edge because they’re tied more closely to hospital personnel, technology, and care pathways than private groups that come from outside the hospital. But there isn’t enough data either way to say which group type is the most efficient. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

While nationwide demand for hospitalists outstrips supply, hospitals across the country are looking at how their hospitalists and their hospital medicine groups weigh in on efficiency.

The notion of efficiency at a time of rapid growth may seem counterintuitive, but healthcare dollars are always hotly contested, and an efficient hospitalist program has a better chance of capturing them than a less-efficient one.

Even the definition of efficiency is being refined. Stakeholders scrutinizing compensation packages, key clinical indicators, productivity and quality metrics, scheduling, average daily census, and patient handoffs to gauge whether or not their group has a competitive edge over others. And hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders are scrutinizing themselves because they know hospitals increasingly are inviting more than one HMG to work under their roofs—the better to serve different populations and compare one with another.

How to Measure Efficiency

An evolving medical discipline that aspires to specialize in internal medicine, hospital medicine is in the process of developing a consensus definition of efficiency for itself. Major variables included in the calculation are obvious: average daily census, length of stay (LOS), case mix-adjusted costs, severity, and readmission rates. Other, harder-to-quantify dimensions include how a hospitalist group practice affects mortality, and how scheduling, variable costs, hospitalist group type, subsidies, and level of expertise play out.

The foundation on which hospitalist groups build their efficiencies is the group type. In itself, how a hospitalist group chooses to organize itself reflects a maturing marketplace. SHM’s 2005-2006 productivity survey shows an increase in multistate hospitalist groups, up from 9% in ’03-’04 to 19% in the latest survey. Local private hospitalist groups fell from 20% in ’03-’04 to 12% in ’05-’06. The percentage of academic hospitalist groups rose from 16% to 20% in the same period.

It’s unclear how to interpret the shift from local to multistate hospitalist groups and the increase in academic medical center programs, but these trends bear watching. Comparison of the two most recent SHM surveys shows compensation models are also growing up, reflecting the need to balance base salary with productivity.

A major indicator of hospital group efficiency is the performance of groups with hospitalists on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although hospital administrators and hospitalist leaders struggle with the economics of providing night coverage when admissions are slow, such coverage pays off in quality and efficiency.

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a healthcare outsourcing firm based in Knoxville, Tenn., has long advocated 24/7 coverage as a crucial element in HMG efficiency. Even though she estimates that night coverage adds approximately $10,000 in subsidies to an average compensation package for a full-time hospitalist, such coverage improves efficiency in length of stay adjusted for severity and in readmissions. Full coverage allows hospitalists to be better integrated into the hospital in a way that fewer hours don’t.

“How hospitalists who cover 24/7 are used varies,” says Dr. Goldsholl. “Doing night admissions for community doctors, [working] as intensivist extenders, helping with ED [emergency department] throughput, being on rapid response teams—all are important contributors to improved efficiency,” says Dr. Goldsholl.

For Dr. Goldsholl, who has at least one academic medical center—Good Samaritan in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine—on her roster, hospitalist group efficiency and productivity are major concerns for academic and community hospital administrators footing the bill for such services.

“Usually, TeamHealth is the exclusive hospitalist medicine provider contracting with a community hospital,” she explains. “Once we have been in a hospital for a while, we tend to see a progression in our responsibilities. Mostly we start with unassigned patients, then we expand to cover private primary care physicians’ patients. Then we co-manage complex cases with sub-specialists.”

Despite operating mostly in community hospitals, Dr. Goldsholl has fielded more queries from academic medical centers (AMCs) in the past several years.

“We’re definitely getting more interest from AMCs,” Dr. Goldsholl notes. “The work-hours restriction on residents—faculty who are uninterested in being hospitalists—whatever is driving their interest, they’re looking for solutions for handling their unassigned patients and beyond. To outsource to a private hospitalist company, an academic medical center would have to be in some pain, but interest is definitely picking up.”

Cogent Healthcare’s June 2006 contract with Temple University Hospital (TUH), Philadelphia, to provide a 24/7 hospitalist program of teaching and non-teaching services is another example of hospitals striving for efficiency. To better reach its clinical, economic, and regulatory goals, TUH switched from its own academic hospitalist group to partner with Cogent to manage its adult medical/surgical population. It’s too soon to gauge the results.

Despite stakeholders’ need to know more about which hospitalist group structure is most efficient, there’s little published data on AMC versus private group efficiency. One important study, published in the American Journal of Medicine (AJM) in May 2005, compared an academic hospitalist group with a private hospitalist group and community internists on several efficiency measures. The academic hospitalists’ patients had a 13% shorter LOS than those patients cared for by other groups and academic hospitalists had lowered costs by $173 per case, versus $109 for the private hospitalist group. The academic hospitalists also had a 20% relative risk reduction for severity of illness over the community physicians.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, the AJM study’s lead author and chair of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee for SHM, speculated that the academic hospitalist groups’ efficiency resulted from fewer handoffs and that academic hospitalists’ relationships with their hospitals were more aligned than those of outsiders, both from financial and quality perspectives. Additionally, the academic hospitalist group used the hospital’s computerized physician order entry system and followed its protocols for clinical pathways and core measures. Scheduling also made a difference. The academic group worked in half-month blocks for an average of 14 weeks, while the private hospitalists worked from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and some nights and weekends, leaving moonlighters to cover 75% of nights, weekends, and holidays and providing for rockier handoffs.

Another study comparing a traditional pediatric faculty group with two private hospitalist groups at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center of Phoenix showed that the faculty group outperformed the private hospitalists on all measures.

The authors concluded that faculty models can be as efficient as or more efficient than private groups in terms of direct costs and LOS.

Fine Tuning

Although academic hospitalist groups have been thought of as less efficient than private hospitalist groups because the former tend to use salaried employees while the latter tend to compensate employees based more on performance, the data cited above indicate academic hospitalist groups may have a competitive edge with regard to efficiency. What may account for the difference is that academic hospitalists are familiar with and often products of their hospital’s culture and mores. Unlike physicians working for private hospitalist groups with their own structure and culture, academic hospitalists are of a piece with their hospital. It’s common to find academic hospitalists who return to their medical school alma mater after a stint in an office-based practice. Some never left, joining the academic hospitalist group directly from residency.

For the chief of a hospitalist program, being so attuned to the hospital’s rhythms can be a mixed blessing.

Pat Cawley, MD, is the hospitalist program director and founder of the academic hospitalist group at the Charleston-based Medical University of South Carolina’s Hospital. He has a hard time focusing on hospitalist group efficiency, though, when he’s still flat-out recruiting.

“Demand for hospitalists is still way outstripping supply,” says Dr. Cawley. “We currently have nine hospitalists and plan to add five more this year, but we could actually use 10 more.”

The South Carolina market is competitive, with other hospitals planning to establish hospitalist medicine programs and vying with Dr. Cawley’s program for fresh physicians. Medical University Hospital’s hospitalist group started in July 2003 with four physicians and has kept growing. The hospitalists spend most of their time functioning as a teaching service and also cover a long-term acute-care facility at another hospital.

Defining efficiency in South Carolina’s booming market is secondary to recruiting and incorporating new physicians as team members. Dr. Cawley uses average daily census (ADC) as an efficiency benchmark: 15-20 patients per hospitalist is productive, although many doctors are comfortable at 12.

“We looked at our learning curve, about 10-12,” points out Dr. Cawley. “We think 15-20 is better, although some places are reporting an ADC of 22. But after a certain point, performance doesn’t appear to improve.”

A big problem with improving hospitalist group efficiency, according to Dr. Cawley, is hospital inefficiency: “Lack of IT to get lab results quickly, not enough nursing and secretarial support for admissions and discharges, policies on contacting the primary doc versus having a standing order for a procedure—all decrease efficiency.”

He’d also like his hospital administrators to allow nurses to pronounce death (common in community hospitals but less so in AMCs). “The power of hospitalists is to challenge the hospital’s inefficiencies, to break down the barriers to more efficient practices,” adds Dr. Cawley. “Many institutions need huge culture change, and hospitalists must lead the way.”

A close watcher of hospitalist performance, Scott Oxenhandler, MD, medical director of the Memorial Hospitalist Group in Hollywood, Fla., heads a hospitalist group he started in June 2004 that now has 23 physicians and two nurse practitioners. Memorial Hospital also has two other private hospitalist groups. While Dr. Oxenhandler’s group handles unassigned patients (55%) and Medicaid/Medicare patients (45%), the other hospitalist groups have captured the more lucrative business of managed care and other commercially insured patients.

—Per Danielsson, MD, medical director, Swedish Medical Center Adult Hospitalist Program, Seattle

Dr. Oxenhandler says efficiency is a complicated issue involving several key components. “Following evidence-based medicine protocols and CMS core measures are fairly straightforward [ideas] for all of us,” he says, “but financial measures are more complex.”

He has taken aim at adjusted variable costs per discharge on lab tests, pharmacy, and radiology, “three areas where I know that our group can improve,” he adds.

As for how hard and how efficiently a hospitalist works, Dr. Oxenhandler is taking a closer look at that as his group and the field mature. “We know that average daily census can be deceiving and RVUs [relative value units] are more relevant to efficiency but not perfect,” he says. “Another factor is tenure with the hospitalist group. For the physician to excel and to mature clinically, he or she needs to stay with a hospitalist group long enough to improve readmission rates and to get a sense of how to better manage clinical resources.’’

Dr. Oxenhandler describes a patient presenting with heart failure and anemia to show how a hospitalist’s clinical skills might mature. After several days of repeated hemoglobin studies indicating anemia, the hospitalist might refer the patient—once stabilized and discharged—to his primary physician for an outpatient work-up for possible colon cancer—rather than do so during the hospitalization.

Dr. Oxenhandler has contemplated pursuing managed care contracts but hesitates because his hospitalist group’s clinical and cost performance is equal to that of the hospitalist group that currently holds such contracts. “Why should they switch to us unless we can outperform the other group?” he muses. “Plus, there would be added cost for us in more paperwork and administration, and we’d have to improve our efficiency to make it worthwhile.”

Per Danielsson, MD, Swedish Medical Center’s Adult Hospitalist Program’s medical director, has hospitalists rotating among the First Hill, Cherry Hill, and Ballard campuses in Seattle, Wash. Demand for hospitalist services at the sites keeps growing, and Dr. Danielsson sees no end in sight. “Today’s hospital stays are getting shorter, and the patients are sicker, and there is increasing pressure for greater efficiency here,” he says.

Overall, clinicians, administrators, and researchers need to zero in on the organizational factors of hospitalist groups—from scheduling to 24/7 coverage, handoffs, and use of in-hospital resources—to improve efficiency. At present, academic hospitalist groups appear to have a slight edge because they’re tied more closely to hospital personnel, technology, and care pathways than private groups that come from outside the hospital. But there isn’t enough data either way to say which group type is the most efficient. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.