User login

An 11-year-old boy is brought to the ED with a 1-week of history of increasing crampy lower-quadrant abdominal pain. His vital signs were only significant for mild tachycardia. On physical examination, the child’s abdomen was tender to palpation in the bilateral lower abdominal quadrants with guarding. Laboratory evaluations were unremarkable.

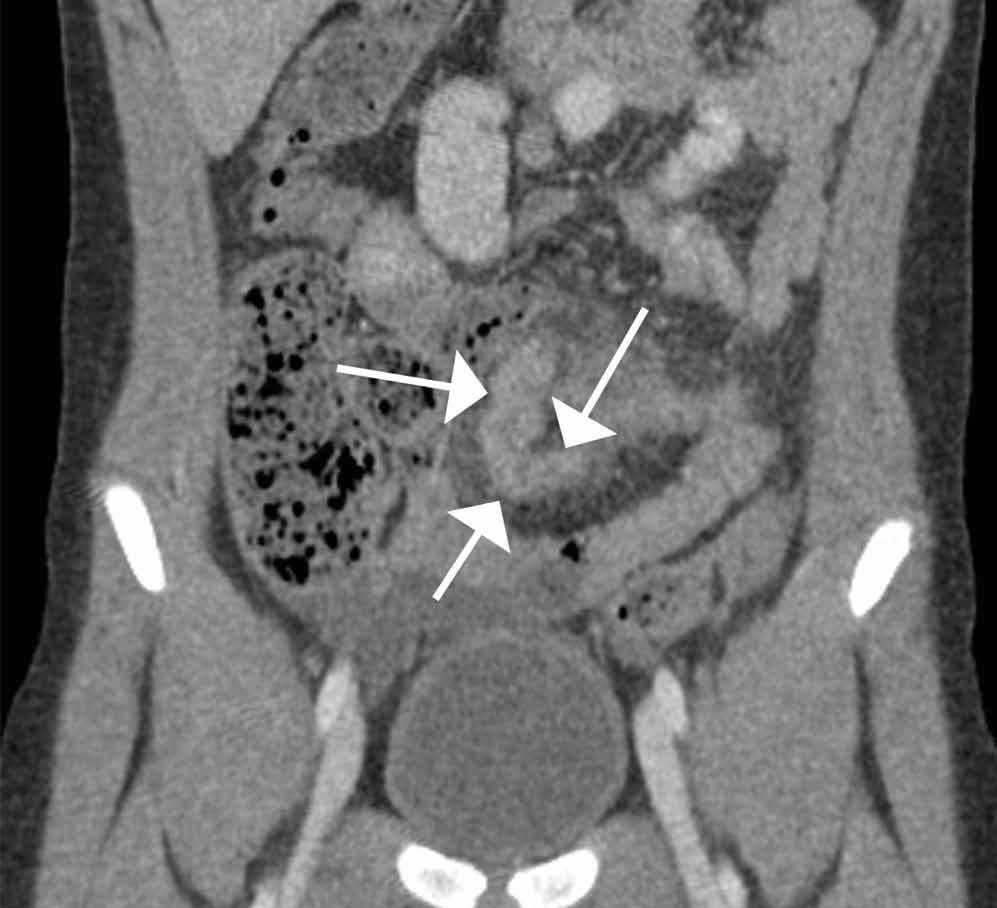

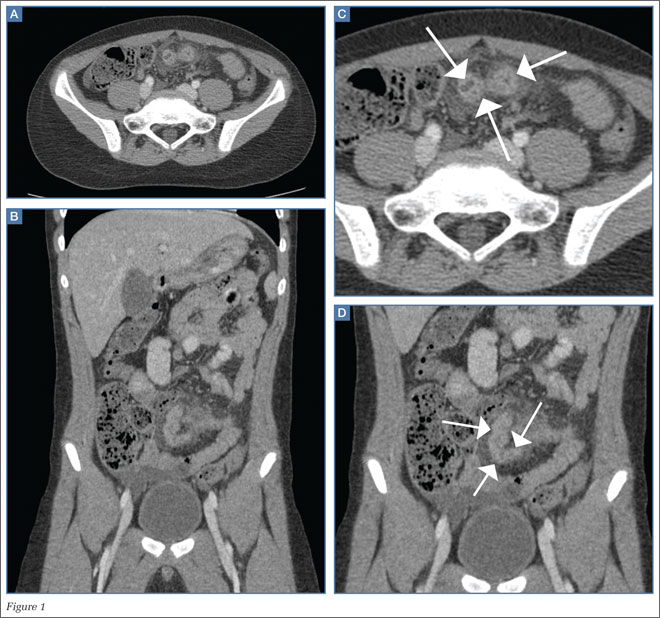

An abdominal radiograph did not reveal any abnormality, and targeted ultrasound did not reveal a dilated appendix. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast were ordered and representative images are provided (Figures 1a and 1b). Note that additional images from the CT demonstrate the abnormality depicted in these figures was not a loop of small bowel (although it appeared to originate from a loop of distal small bowel) and that the appendix was normal.

|

|

|

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

Computed tomography revealed a blind-ending tubular structure (white arrows, Figure 1c) deep to the umbilicus arising inferiorly from a loop of distal ileum with surrounding fat stranding (Figure 1d). The fluid-containing tubular structure demonstrates marked enhancement of the mucosa. These findings are most consistent with Meckel’s diverticulitis.

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common anomaly of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and results from incomplete obliteration of the vitelline duct. As per the rule of “twos,” Meckel’s diverticulum usually occurs 2 feet (40-60 cm) proximal to the ileocecal valve; is 2 cm wide (and 3 cm long); is found in 2% of the population; typically presents before age 2 years; is twice as likely to be symptomatic in boys; and contains ectopic gastric mucosa in approximately half of the cases.1

|

|

|

As many patients are asymptomatic, Meckel’s diverticulum is diagnosed as an incidental finding after a barium study or abdominal surgery is performed for other GI conditions. Symptoms occur as a result of ectopic gastric tissue, obstruction, and/or inflammation. Painless lower GI bleeding, the most common presentation, is reported in up to 50% of patients with symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulosis.2 Hemorrhage results from ulceration caused by secreted acid and enzymes from ectopic digestive mucosa. Intestinal obstruction is another common complication usually seen in children, which can be caused by volvulus of the small bowel around a diverticulum, intussusception, incarceration within a hernia, and internal herniation. Inflammation of the Meckel’s diverticulum, or Meckel’s diverticulitis, is more common in older patients and presents similarly to acute appendicitis.2

After removal of a complicated Meckel’s diverticulitis, postoperative morbidity and mortality rates have been reported to be 12% and 2%, respectively. In contrast, postoperative complications after resection of incidental diverticula are fewer, and morbidity and mortality rates are as low as 2% and 1%, respectively.3-5 Meckel’s diverticulitis should be included as a differential diagnosis when appendicitis or medically managed abdominopelvic inflammatory processes are suspected, as delayed diagnosis can lead to perforation, abscess formation, peritonitis, sepsis, bowel obstruction, and death.

The patient presented in this case was taken to the operating room, and the Meckel’s diverticula confirmed and removed. He experienced an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged a few days later.

Dr Rotman is a radiology resident at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Anderson DJ. Carcinoid tumor in Meckel’s diverticulum: laparoscopic treatment and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(7):432-434.

- Malik AA, Shams-ul-Bari, Wani KA, Khaja AR. Meckel’s diverticulum-Revisited. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(1):3-7.

- Altinli E, Pekmezci S, Gorgun E, Sirin F. Laparoscopy-assisted resection of complicated Meckel’s diverticulum in adults. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12(3):190-194.

- Nath, DS, Morris TA. Small bowel obstruction in an adolescent: a case of Meckel’s diverticulum. Minn Med. 2004;87(11):46-48.

- Cullen, JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, et al. Surgical management of Meckel’s diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220(4):564-568; discussion 568,569.

An 11-year-old boy is brought to the ED with a 1-week of history of increasing crampy lower-quadrant abdominal pain. His vital signs were only significant for mild tachycardia. On physical examination, the child’s abdomen was tender to palpation in the bilateral lower abdominal quadrants with guarding. Laboratory evaluations were unremarkable.

An abdominal radiograph did not reveal any abnormality, and targeted ultrasound did not reveal a dilated appendix. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast were ordered and representative images are provided (Figures 1a and 1b). Note that additional images from the CT demonstrate the abnormality depicted in these figures was not a loop of small bowel (although it appeared to originate from a loop of distal small bowel) and that the appendix was normal.

|

|

|

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

Computed tomography revealed a blind-ending tubular structure (white arrows, Figure 1c) deep to the umbilicus arising inferiorly from a loop of distal ileum with surrounding fat stranding (Figure 1d). The fluid-containing tubular structure demonstrates marked enhancement of the mucosa. These findings are most consistent with Meckel’s diverticulitis.

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common anomaly of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and results from incomplete obliteration of the vitelline duct. As per the rule of “twos,” Meckel’s diverticulum usually occurs 2 feet (40-60 cm) proximal to the ileocecal valve; is 2 cm wide (and 3 cm long); is found in 2% of the population; typically presents before age 2 years; is twice as likely to be symptomatic in boys; and contains ectopic gastric mucosa in approximately half of the cases.1

|

|

|

As many patients are asymptomatic, Meckel’s diverticulum is diagnosed as an incidental finding after a barium study or abdominal surgery is performed for other GI conditions. Symptoms occur as a result of ectopic gastric tissue, obstruction, and/or inflammation. Painless lower GI bleeding, the most common presentation, is reported in up to 50% of patients with symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulosis.2 Hemorrhage results from ulceration caused by secreted acid and enzymes from ectopic digestive mucosa. Intestinal obstruction is another common complication usually seen in children, which can be caused by volvulus of the small bowel around a diverticulum, intussusception, incarceration within a hernia, and internal herniation. Inflammation of the Meckel’s diverticulum, or Meckel’s diverticulitis, is more common in older patients and presents similarly to acute appendicitis.2

After removal of a complicated Meckel’s diverticulitis, postoperative morbidity and mortality rates have been reported to be 12% and 2%, respectively. In contrast, postoperative complications after resection of incidental diverticula are fewer, and morbidity and mortality rates are as low as 2% and 1%, respectively.3-5 Meckel’s diverticulitis should be included as a differential diagnosis when appendicitis or medically managed abdominopelvic inflammatory processes are suspected, as delayed diagnosis can lead to perforation, abscess formation, peritonitis, sepsis, bowel obstruction, and death.

The patient presented in this case was taken to the operating room, and the Meckel’s diverticula confirmed and removed. He experienced an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged a few days later.

Dr Rotman is a radiology resident at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

An 11-year-old boy is brought to the ED with a 1-week of history of increasing crampy lower-quadrant abdominal pain. His vital signs were only significant for mild tachycardia. On physical examination, the child’s abdomen was tender to palpation in the bilateral lower abdominal quadrants with guarding. Laboratory evaluations were unremarkable.

An abdominal radiograph did not reveal any abnormality, and targeted ultrasound did not reveal a dilated appendix. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast were ordered and representative images are provided (Figures 1a and 1b). Note that additional images from the CT demonstrate the abnormality depicted in these figures was not a loop of small bowel (although it appeared to originate from a loop of distal small bowel) and that the appendix was normal.

|

|

|

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

Computed tomography revealed a blind-ending tubular structure (white arrows, Figure 1c) deep to the umbilicus arising inferiorly from a loop of distal ileum with surrounding fat stranding (Figure 1d). The fluid-containing tubular structure demonstrates marked enhancement of the mucosa. These findings are most consistent with Meckel’s diverticulitis.

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common anomaly of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and results from incomplete obliteration of the vitelline duct. As per the rule of “twos,” Meckel’s diverticulum usually occurs 2 feet (40-60 cm) proximal to the ileocecal valve; is 2 cm wide (and 3 cm long); is found in 2% of the population; typically presents before age 2 years; is twice as likely to be symptomatic in boys; and contains ectopic gastric mucosa in approximately half of the cases.1

|

|

|

As many patients are asymptomatic, Meckel’s diverticulum is diagnosed as an incidental finding after a barium study or abdominal surgery is performed for other GI conditions. Symptoms occur as a result of ectopic gastric tissue, obstruction, and/or inflammation. Painless lower GI bleeding, the most common presentation, is reported in up to 50% of patients with symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulosis.2 Hemorrhage results from ulceration caused by secreted acid and enzymes from ectopic digestive mucosa. Intestinal obstruction is another common complication usually seen in children, which can be caused by volvulus of the small bowel around a diverticulum, intussusception, incarceration within a hernia, and internal herniation. Inflammation of the Meckel’s diverticulum, or Meckel’s diverticulitis, is more common in older patients and presents similarly to acute appendicitis.2

After removal of a complicated Meckel’s diverticulitis, postoperative morbidity and mortality rates have been reported to be 12% and 2%, respectively. In contrast, postoperative complications after resection of incidental diverticula are fewer, and morbidity and mortality rates are as low as 2% and 1%, respectively.3-5 Meckel’s diverticulitis should be included as a differential diagnosis when appendicitis or medically managed abdominopelvic inflammatory processes are suspected, as delayed diagnosis can lead to perforation, abscess formation, peritonitis, sepsis, bowel obstruction, and death.

The patient presented in this case was taken to the operating room, and the Meckel’s diverticula confirmed and removed. He experienced an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged a few days later.

Dr Rotman is a radiology resident at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Anderson DJ. Carcinoid tumor in Meckel’s diverticulum: laparoscopic treatment and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(7):432-434.

- Malik AA, Shams-ul-Bari, Wani KA, Khaja AR. Meckel’s diverticulum-Revisited. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(1):3-7.

- Altinli E, Pekmezci S, Gorgun E, Sirin F. Laparoscopy-assisted resection of complicated Meckel’s diverticulum in adults. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12(3):190-194.

- Nath, DS, Morris TA. Small bowel obstruction in an adolescent: a case of Meckel’s diverticulum. Minn Med. 2004;87(11):46-48.

- Cullen, JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, et al. Surgical management of Meckel’s diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220(4):564-568; discussion 568,569.

- Anderson DJ. Carcinoid tumor in Meckel’s diverticulum: laparoscopic treatment and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(7):432-434.

- Malik AA, Shams-ul-Bari, Wani KA, Khaja AR. Meckel’s diverticulum-Revisited. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(1):3-7.

- Altinli E, Pekmezci S, Gorgun E, Sirin F. Laparoscopy-assisted resection of complicated Meckel’s diverticulum in adults. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12(3):190-194.

- Nath, DS, Morris TA. Small bowel obstruction in an adolescent: a case of Meckel’s diverticulum. Minn Med. 2004;87(11):46-48.

- Cullen, JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, et al. Surgical management of Meckel’s diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220(4):564-568; discussion 568,569.