User login

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

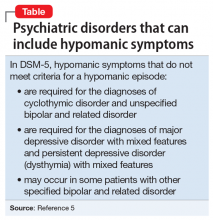

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.