User login

NEW ORLEANS – The key message of the SPRINT trial – that aggressive antihypertensive therapy to a target systolic blood pressure (SBP) of less than 120 mm Hg reduces all-cause mortality, compared with a target SBP under 140 mm Hg – is not broadly applicable as a routine strategy in managing hypertension, experts declared at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“My concern is that the patients in the SPRINT trial ended up being highly selected for having a strong ability to achieve and tolerate being at systolic blood pressure levels that we generally don’t see in a lot of treated hypertensives today in this country,” cautioned Peter M. Okin, MD, of Columbia University, New York.

It will be interesting to see how Dr. Okin’s opinion, which is shared by many leading cardiologists, is addressed in new hypertension treatment guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. The guidelines are anticipated in March.

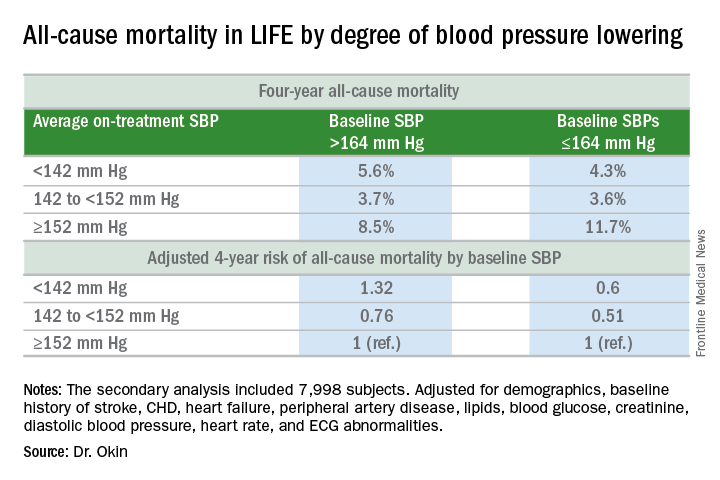

Dr. Okin presented a secondary analysis of the earlier landmark LIFE (Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension) trial that’s diametrically at odds with the main finding in SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial): namely, in LIFE (Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359[9311]:1004-10), all-cause mortality during follow-up was heavily dependent upon baseline blood pressure.

Among LIFE participants with a baseline SBP below 164 mm Hg, achievement of an average on-treatment SBP below 142 mm Hg was associated with a 40% reduction in all-cause mortality more than 4 years of follow-up, compared with those with an achieved SBP of 152 mm Hg or more. In contrast, LIFE subjects whose baseline SBP was greater than 164 mm Hg actually had a 32% increase in all-cause mortality if their achieved SBP was less than 142 mm Hg, compared with those whose average on-treatment SBP was 152 mm Hg or higher.

How to account for the disparate results of LIFE and SPRINT?

SPRINT (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26; 373:2103-16) enrolled nondiabetic patients aged 50 years or older who had an SBP of 130 mm Hg or more and high cardiovascular risk, with a 10-year Framingham Risk Score greater than 15%. But because the SBP threshold for entry was set so low, at 130 mm Hg, roughly half of SPRINT participants had baseline SBP levels that were already at or below the standard treatment target of 140 mm Hg. For those patients, getting to roughly 120 mm Hg on treatment wasn’t all that big a stretch in terms of the magnitude of blood pressure reduction, Dr. Okin said.

“Our analysis doesn’t invalidate SPRINT in any way, shape, or fashion. It just gives us some pause for thought,” he added.

His post-hoc analysis of LIFE was restricted to the 7,998 participants without diabetes at baseline, since SPRINT excluded diabetics from enrollment.

Audience comments were split between cardiologists who consider SPRINT a game-changer in the treatment of hypertension and those who, like Dr. Okin, have reservations. Among those reservations was the unexpected and difficult-to-explain finding that aggressive SBP lowering didn’t reduce the risk of stroke, compared with less-intensive SBP lowering, unlike the case in other clinical trials and epidemiologic studies in hypertension. Also, audience members took issue with the fact that blood pressure measurements in SPRINT weren’t done in the standard office measurement way employed in other major trials. Instead, SPRINT relied upon automated blood pressure monitoring of a patient alone in a room, which several cardiologists in the audience thought might have skewed the study results, since automated measurements tend to run lower.

Elsewhere at the AHA meeting, former AHA president Clyde W. Yancy, MD, offered a cautionary note regarding SPRINT.

“I think it’s important that we emphasize to this audience that SPRINT is looking at a very select patient population that probably describes only 15% of those with hypertension, specifically those with very high cardiovascular disease risk profiles. So we have to be very careful when we take the blood pressure targets that were identified in SPRINT and try to extrapolate those to other populations,” said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Okin reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

NEW ORLEANS – The key message of the SPRINT trial – that aggressive antihypertensive therapy to a target systolic blood pressure (SBP) of less than 120 mm Hg reduces all-cause mortality, compared with a target SBP under 140 mm Hg – is not broadly applicable as a routine strategy in managing hypertension, experts declared at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“My concern is that the patients in the SPRINT trial ended up being highly selected for having a strong ability to achieve and tolerate being at systolic blood pressure levels that we generally don’t see in a lot of treated hypertensives today in this country,” cautioned Peter M. Okin, MD, of Columbia University, New York.

It will be interesting to see how Dr. Okin’s opinion, which is shared by many leading cardiologists, is addressed in new hypertension treatment guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. The guidelines are anticipated in March.

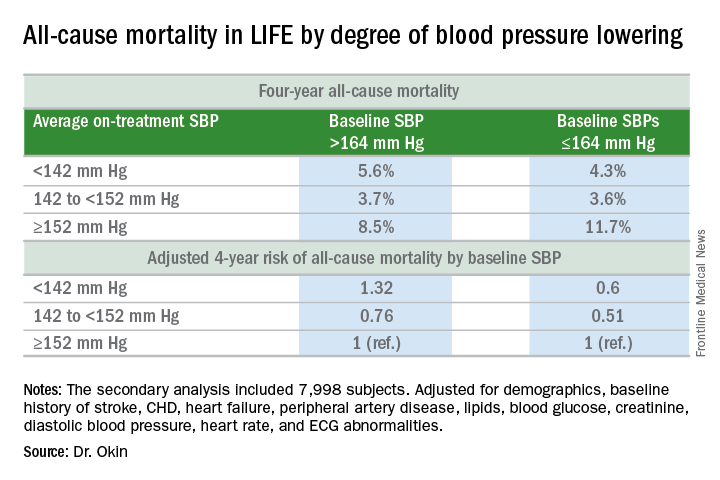

Dr. Okin presented a secondary analysis of the earlier landmark LIFE (Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension) trial that’s diametrically at odds with the main finding in SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial): namely, in LIFE (Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359[9311]:1004-10), all-cause mortality during follow-up was heavily dependent upon baseline blood pressure.

Among LIFE participants with a baseline SBP below 164 mm Hg, achievement of an average on-treatment SBP below 142 mm Hg was associated with a 40% reduction in all-cause mortality more than 4 years of follow-up, compared with those with an achieved SBP of 152 mm Hg or more. In contrast, LIFE subjects whose baseline SBP was greater than 164 mm Hg actually had a 32% increase in all-cause mortality if their achieved SBP was less than 142 mm Hg, compared with those whose average on-treatment SBP was 152 mm Hg or higher.

How to account for the disparate results of LIFE and SPRINT?

SPRINT (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26; 373:2103-16) enrolled nondiabetic patients aged 50 years or older who had an SBP of 130 mm Hg or more and high cardiovascular risk, with a 10-year Framingham Risk Score greater than 15%. But because the SBP threshold for entry was set so low, at 130 mm Hg, roughly half of SPRINT participants had baseline SBP levels that were already at or below the standard treatment target of 140 mm Hg. For those patients, getting to roughly 120 mm Hg on treatment wasn’t all that big a stretch in terms of the magnitude of blood pressure reduction, Dr. Okin said.

“Our analysis doesn’t invalidate SPRINT in any way, shape, or fashion. It just gives us some pause for thought,” he added.

His post-hoc analysis of LIFE was restricted to the 7,998 participants without diabetes at baseline, since SPRINT excluded diabetics from enrollment.

Audience comments were split between cardiologists who consider SPRINT a game-changer in the treatment of hypertension and those who, like Dr. Okin, have reservations. Among those reservations was the unexpected and difficult-to-explain finding that aggressive SBP lowering didn’t reduce the risk of stroke, compared with less-intensive SBP lowering, unlike the case in other clinical trials and epidemiologic studies in hypertension. Also, audience members took issue with the fact that blood pressure measurements in SPRINT weren’t done in the standard office measurement way employed in other major trials. Instead, SPRINT relied upon automated blood pressure monitoring of a patient alone in a room, which several cardiologists in the audience thought might have skewed the study results, since automated measurements tend to run lower.

Elsewhere at the AHA meeting, former AHA president Clyde W. Yancy, MD, offered a cautionary note regarding SPRINT.

“I think it’s important that we emphasize to this audience that SPRINT is looking at a very select patient population that probably describes only 15% of those with hypertension, specifically those with very high cardiovascular disease risk profiles. So we have to be very careful when we take the blood pressure targets that were identified in SPRINT and try to extrapolate those to other populations,” said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Okin reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

NEW ORLEANS – The key message of the SPRINT trial – that aggressive antihypertensive therapy to a target systolic blood pressure (SBP) of less than 120 mm Hg reduces all-cause mortality, compared with a target SBP under 140 mm Hg – is not broadly applicable as a routine strategy in managing hypertension, experts declared at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“My concern is that the patients in the SPRINT trial ended up being highly selected for having a strong ability to achieve and tolerate being at systolic blood pressure levels that we generally don’t see in a lot of treated hypertensives today in this country,” cautioned Peter M. Okin, MD, of Columbia University, New York.

It will be interesting to see how Dr. Okin’s opinion, which is shared by many leading cardiologists, is addressed in new hypertension treatment guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. The guidelines are anticipated in March.

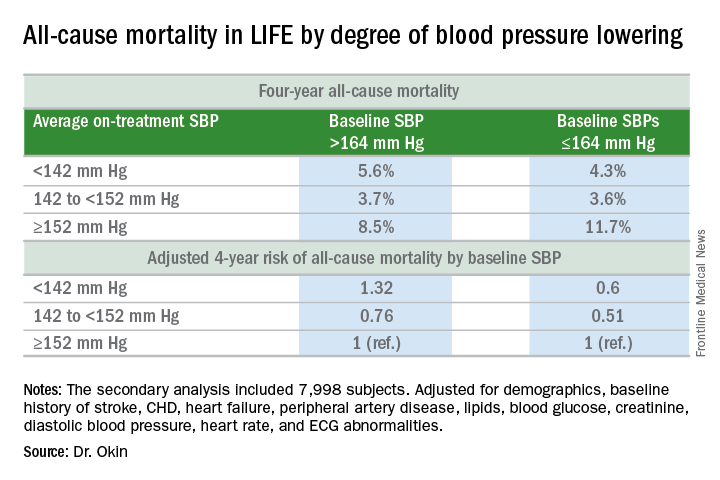

Dr. Okin presented a secondary analysis of the earlier landmark LIFE (Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension) trial that’s diametrically at odds with the main finding in SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial): namely, in LIFE (Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359[9311]:1004-10), all-cause mortality during follow-up was heavily dependent upon baseline blood pressure.

Among LIFE participants with a baseline SBP below 164 mm Hg, achievement of an average on-treatment SBP below 142 mm Hg was associated with a 40% reduction in all-cause mortality more than 4 years of follow-up, compared with those with an achieved SBP of 152 mm Hg or more. In contrast, LIFE subjects whose baseline SBP was greater than 164 mm Hg actually had a 32% increase in all-cause mortality if their achieved SBP was less than 142 mm Hg, compared with those whose average on-treatment SBP was 152 mm Hg or higher.

How to account for the disparate results of LIFE and SPRINT?

SPRINT (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26; 373:2103-16) enrolled nondiabetic patients aged 50 years or older who had an SBP of 130 mm Hg or more and high cardiovascular risk, with a 10-year Framingham Risk Score greater than 15%. But because the SBP threshold for entry was set so low, at 130 mm Hg, roughly half of SPRINT participants had baseline SBP levels that were already at or below the standard treatment target of 140 mm Hg. For those patients, getting to roughly 120 mm Hg on treatment wasn’t all that big a stretch in terms of the magnitude of blood pressure reduction, Dr. Okin said.

“Our analysis doesn’t invalidate SPRINT in any way, shape, or fashion. It just gives us some pause for thought,” he added.

His post-hoc analysis of LIFE was restricted to the 7,998 participants without diabetes at baseline, since SPRINT excluded diabetics from enrollment.

Audience comments were split between cardiologists who consider SPRINT a game-changer in the treatment of hypertension and those who, like Dr. Okin, have reservations. Among those reservations was the unexpected and difficult-to-explain finding that aggressive SBP lowering didn’t reduce the risk of stroke, compared with less-intensive SBP lowering, unlike the case in other clinical trials and epidemiologic studies in hypertension. Also, audience members took issue with the fact that blood pressure measurements in SPRINT weren’t done in the standard office measurement way employed in other major trials. Instead, SPRINT relied upon automated blood pressure monitoring of a patient alone in a room, which several cardiologists in the audience thought might have skewed the study results, since automated measurements tend to run lower.

Elsewhere at the AHA meeting, former AHA president Clyde W. Yancy, MD, offered a cautionary note regarding SPRINT.

“I think it’s important that we emphasize to this audience that SPRINT is looking at a very select patient population that probably describes only 15% of those with hypertension, specifically those with very high cardiovascular disease risk profiles. So we have to be very careful when we take the blood pressure targets that were identified in SPRINT and try to extrapolate those to other populations,” said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Okin reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS