User login

Dermatology has become one of the most competitive, if not the most competitive, medical specialties to enter. It attracts the brightest and most accomplished medical students who have excelled not only in the classroom and clinical setting but also in the research setting. Many successful applicants take a substantial amount of time off to pursue research and publish articles.

Despite the competitive nature of the specialty, it is well known that a marked shortage of academic dermatologists has existed for more than 30 years.1-3 In fact, the number of graduates from US dermatology residency programs who pursue academic careers has progressively declined.4 Nearly all dermatology residents have a strong academic background; however, many residents opt to pursue private practice instead of a career in academia.5-9 This trend has implications not only for future dermatology research but also for the teaching and training of future generations of dermatologists.8

To address this shortage, it is important to recruit dermatology residents who have a genuine interest in pursuing academic careers. Unfortunately, many residency applicants may overinflate their interest in academics to boost their chances of acceptance.4 Additionally, it has been shown that dermatology residents who were interested in academic careers at the time of application to the program often lost interest during residency.10

Because it can be difficult to determine a resident’s true interest in an academic career at the time of application and his/her initial interest may wean during residency, it may be more helpful to encourage dermatology residency programs to create environments that will produce residents who are more enthusiastic about and more likely to pursue careers in academia. A lack of mentorship has been shown to be associated with a loss of interest in academic careers during residency.10 If better mentorship opportunities were provided, then perhaps dermatology residents would be more likely to pursue careers in teaching and research.

A 2006 study by Wu et al5 demonstrated that various program characteristics were associated with the pursuit of academic careers among dermatology residents. The number of faculty members and the number of full-time faculty publications at a given residency program were most strongly correlated with the number of residents who pursued academic careers, which suggested that having a large faculty and encouraging dermatology residents to publish research during residency may motivate their pursuit of academic careers in dermatology.5 The current study was designed to replicate these data and respond to limitations in the original study.

Methods

Data were collected from all accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States as of December 31, 2008. The names of all full-time faculty members at these resident programs were obtained, and it was determined where each faculty member attended dermatology residency. The number of graduates who became full-time clinical or research faculty members and the number of graduates who became chairs or chiefs were counted. Residency programs excluded from these analyses included The University of Texas at Austin, University of Texas Medical Branch, and University of Connecticut, which commenced in 2008, as well as Kaiser Permanente Southern California, which commenced in 2010. Residency programs that were started after 2004 were excluded from the study, as it was thought that these programs may not have graduated a sufficient number of residents for assessment. Military residency programs also were excluded, as graduates from these programs often do not freely choose their careers after residency, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) dermatology residency program was excluded because it is not a traditional 3-year residency program.

The primary end point was the ratio of full-time faculty members graduated to the total number of graduates from each dermatology residency program. Based on a prior study by Wu et al5 in 2006, it was believed that several program variables might affect pursuit of academic careers among dermatology residents, including total number of full-time faculty members, total number of residents, NIH funding received (in dollars) in 2008 (http://www.report.nih.gov/award/index.cfm), Dermatology Foundation (DF) funding received (in dollars) in 2008 (http://www.dermatology foundation.org/rap/), number of publications from full-time faculty members in 2008 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), number of full-time faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2008 (American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the American Society of Dermatopathology, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery), number of faculty members on the editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals (Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Archives of Dermatology [currently known as JAMA Dermatology], Dermatologic Surgery, Pediatric Dermatology, and Journal of Cutaneous Pathology), and status as a department of dermatology or a division of internal medicine. The association between the ratio of number of full-time faculty members to number of residents for each residency program were determined for each of the outcome variables because they were believed to serve as an indicator of mentorship.

Data regarding faculty and residents were obtained from program Web sites and inquiries from individual programs. The year 1974 was used as a cutoff for the total number of graduates from each program. For faculty members who split time between 2 residency programs, each program was given credit for the duration of time spent at that program. If it was not clear how long the faculty member spent at each program, a credit of 1.5 years was given, which is half the duration of a dermatology residency. Faculty members who held a PhD only and those who completed their residencies in non-US dermatology residency programs were excluded from the outcome variables. To avoid duplicate faculty publications, collections for each residency program were created within PubMed (ie, if 2 authors from the same program coauthored an article, it was only counted once toward the total number of faculty publications from that program).

Descriptive exploratory statistical analysis in the form of a correlation matrix was completed to determine the most strongly positive and negative variables that were correlated with the ratio of graduating full-time faculty to estimated total graduates. Variables also were correlated with the secondary outcomes of ratio of graduating department chairs/chiefs to estimated total number of graduates and ratio of graduating program directors to estimated total number of graduates. Spearman rank correlation coefficients and P values were reported. Additionally, a 2-sample t test was performed to compare primary and secondary outcome variables between dermatology department versus division of dermatology under the department of internal medicine. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2. The institutional review board at Kaiser Permanente Southern California approved this study.

Results

Due to space considerations, analyses are based on data that are not published in this article. Data regarding the characteristics of each residency program are available from the authors.

Data from 103 dermatology residency programs were included in the analysis. Of these programs, 43% had received NIH funding in 2008 and 22% had received DF funding. Two-thirds of programs had at least 1 faculty member on the editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals; 38% had at least 2 faculty members and 9% had at least 5 faculty members on editorial boards. One-third of programs had no faculty members on these editorial boards. Sixty-nine percent of programs had 1 or more lectures given by full-time faculty members at annual society meetings in 2008; 48% of these programs had 1 to 5 lectures, 17% had 6 to 10, and 5% had more than 10. Thirty-one percent had no faculty members lecture at these meetings. Ninety-six percent of programs had 1 or more publications from full-time faculty members in 2008; 54% of programs had 1 to 20 publications, 24% had 21 to 40 publications, 14% had 41 to 60 publications, 5% had 61 to 80 publications, and 3% had more than 81 publications. Four percent of programs had no publications. Seventy-seven percent of programs were classified as departments and 23% were classified as divisions.

Factors Correlated With Producing Full-time Faculty

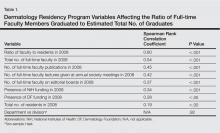

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient and P value were reported for each variable (Table 1). All coefficients were positive, signifying a positive correlation. Values closer to 1 were indicative of stronger correlations. P<.05 indicated statistically significant correlations for all factors investigated. The most strongly correlated factor was the ratio of faculty to residents in 2008, followed by number of full-time faculty, number of full-time faculty publications, number of lectures from full-time faculty, and number of faculty on editorial boards. The amount of NIH and DF funding received as well as total number of residents in 2008 also were correlated.

A 2-sample t test was performed to compare the number of graduates pursuing careers in academia from departments versus divisions, but the results were not statistically significant (P=.92).

Ranking Individual Programs With the Highest Number of Graduates Pursuing Academic Careers

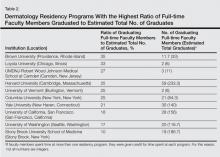

The top 5 dermatology residency programs with the highest ratio of full-time faculty members graduated to the estimated total number of graduates were Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), Loyola University (Chicago, Illinois), UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Camden (Camden, New Jersey), Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts), and the University of Vermont (Burlington, Vermont)(Table 2). If faculty members spent time at more than one residency program, they were given credit for time spent at each program. For this reason, not all numbers are integers.

Ranking Individual Programs With the Highest Number of Full-time Faculty Members Who Completed Residency at the Same Institution

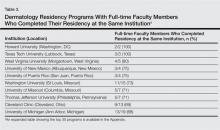

The top 10 institutions with the highest percentage of full-time faculty members who completed their residency at the same institution are shown in Table 3. Most of the programs with higher percentages are small programs. Fourteen programs had no faculty members who completed residency at the same program (data not shown).

Comment

Although this study focused on US dermatology residency programs, a shortage of academic dermatologists has been noted worldwide.11-13 By determining residency program variables associated with the pursuit of academic careers, individual programs may be able to make changes that would encourage residents to pursue careers in academia following graduation.

The factor most strongly correlated with graduates pursuing a career in academics was the ratio of faculty to residents in 2008. Also highly correlated was total number of full-time faculty members. We hypothesize that programs with more faculty members may provide better mentorship for residents. A study by Reck et al10 demonstrated that a lack of mentorship was associated with residents’ loss of interest in academics. A survey of residency program directors demonstrated that mentorship played a role in career development and that it was important for residents to have mentors.14 Given the shortage of academic faculty, increasing the number of faculty may not be feasible for individual programs; however, assuming that more faculty members is a marker for mentorship, there are many ways that individual programs may improve mentorship. There are ample opportunities in clinics to demonstrate to residents the value of research to patient care.13 Residency programs also could establish mentorship programs, pairing residents with individual faculty members who share similar interests. Some programs currently have such mentorship programs but many do not.

Also strongly correlated with the number of graduates pursuing careers in academia was the number of full-time faculty publications. It is presumed that these programs also have published extensively in the past, which may have positively influenced the programs’ residents toward academics. This factor can be easily addressed among individual residency programs, and in fact many residency programs do encourage or require residents to publish during their residency. Exposure to the process of collecting data and writing manuscripts can bolster a resident’s interest in academics. In a prior study by Wu et al,5 publications were counted multiple times if multiple faculty members were authors. This limitation was addressed by only counting each manuscript once.

Other variables correlated with the number of graduates pursuing academic careers included number of lectures from full-time faculty members at annual society meetings, number of full-time faculty on editorial boards, and amount of NIH and DF funding received. All of these variables represent the importance of establishing an academic environment and promoting dermatology research. A 2009 study by Lim and Kimball,15 which also evaluated factors associated with pursuing a career in academics, demonstrated that the number of publications prior to residency and volunteerism were associated with an academic career choice. Residents with an MD/PhD were more likely to pursue a career in academics, which also was demonstrated by a similar study in 2008.16

Wu et al5 demonstrated similar results using data from 2001 to 2004; however, amount of NIH and DF funding received was found to be negatively correlated with graduates pursuing a career in academics in the original study. This finding was surprising but was not replicated in the current study. In the current study, the amount of funding (in dollars) rather than number of grants was analyzed because it was felt that the amount of funding received was a better reflection of the quantity of research being conducted. The prior study examined the relationship between the number of grants received and the number of graduates pursuing a career in academics. It is unclear why results varied in the 2 studies, but the most recent data are consistent with our hypothesis that increased research funding is associated with more residents pursuing careers in academia.

The current study also has some limitations. It is a retrospective observational study looking at data from 2008. Choosing data from another study period may have provided different results; however, it is reassuring that the data from the current study were very similar to a prior study looking at data from 2001 to 2004.5

It is assumed that residency program characteristics remained constant over time. It was also assumed that the number of residents in a program remained constant over time. These assumptions were necessary to draw conclusions about the data. It may be that some programs have changed substantially over time, which was not accounted for in the current study. To estimate the total number of graduates, it was assumed that faculty did not practice for more than 35 years, which may not have been true; if the faculty member practiced more than 35 years, it would have altered our estimates. It is also assumed that data on residency programs’ Web sites at time of data collection were updated and accurate. It is likely that data were not 100% accurate on all Web sites at the time of data collection. However, verification of accuracy of data would have been cumbersome, and it would have been difficult to get participation from all programs.

This study does not differentiate the total number of new faculty members who join a residency program and those who are retained for many years. Encouraging residents to pursue a career in academics may increase the number of academic faculty.17 However, efforts must also be placed on retention of faculty members because many of the newly graduated residents who enter academics ultimately leave.18,19

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data suggest that programs with more faculty members may encourage residents to enter careers in academia following graduation. Additionally, the number of publications increases the likelihood of residents pursuing academic careers. By providing mentorship and research opportunities to residents, perhaps residency programs can encourage their graduates to become academic dermatologists. A program’s overall academic environment, including faculty lectures at annual society meetings, faculty on editorial boards, and increased research funding are all associated with graduates pursuing careers in academics.

Ackowledgements—We thank all of the program coordinators, full-time faculty members, program directors, chairs, and chiefs who were kind enough to field our questions if we had any missing data about their programs. We would like to thank Mary H. Black, PhD (Los Angeles, California), for her contribution to the analytical plan.

APPENDIX

1. Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, Lynch PJ, et al. Shortage of full-time faculty in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:529-532.

2. Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, Caro I. Shortage of full-time faculty in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:297-301.

3. Resneck J. Too few or too many academic dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

4. Kia KF, Gielczyk RA, Ellis CN. Academia is the life for me, I’m sure. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:911-913.

5. Wu JJ, Ramirez CC, Alonso CA, et al. Dermatology residency program characteristics that correlate with graduates selecting an academic dermatology career. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:845-850.

6. Wu JJ, Tyring SK. The academic strength of current dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:22.

7. Hinchman KF, Wu JJ. Decisions in choosing a career in academic dermatology. Cutis. 2008;82:368-371.

8. Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

9. Rubenstein DS, Blauvelt A, Chen SC, et al. The future of academic dermatology in the United States: report on the resident retreat for future physician-scientists, June 15-17, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:300-303.

10. Reck SJ, Stratman EJ, Vogel C, et al. Assessment of residents’ loss of interest in academic careers and identification of correctable factors. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:855-858.

11. Olerud JE. Academic workforce in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:409-410.

12. Singer N. More doctors turning to the business of beauty. New York Times. November 30, 2006:A1.

13. Dogra S. Fate of medical dermatology in the era of cosmetic dermatology and dermatosurgery. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:4-7.

14. Donovan JC. A survey of dermatology residency program directors’ views on mentorship. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

15. Lim JL, Kimball AB. Residency applications and identification of factors associated with residents’ ultimate career decisions. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:943-944.

16. Wu JJ, Davis KF, Ramirez CC, et al. MD/PhDs are more likely than MDs to choose a career in academics. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:27.

17. Wu JJ. Current strategies to address the ongoing shortage of academic dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1065-1066.

18. Loo DS, Liu CL, Geller AC, et al. Academic dermatology manpower. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:341-347.

19. Turner E, Yoo J, Salter S, et al. Leadership workforce in academic dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:948-949.

Dermatology has become one of the most competitive, if not the most competitive, medical specialties to enter. It attracts the brightest and most accomplished medical students who have excelled not only in the classroom and clinical setting but also in the research setting. Many successful applicants take a substantial amount of time off to pursue research and publish articles.

Despite the competitive nature of the specialty, it is well known that a marked shortage of academic dermatologists has existed for more than 30 years.1-3 In fact, the number of graduates from US dermatology residency programs who pursue academic careers has progressively declined.4 Nearly all dermatology residents have a strong academic background; however, many residents opt to pursue private practice instead of a career in academia.5-9 This trend has implications not only for future dermatology research but also for the teaching and training of future generations of dermatologists.8

To address this shortage, it is important to recruit dermatology residents who have a genuine interest in pursuing academic careers. Unfortunately, many residency applicants may overinflate their interest in academics to boost their chances of acceptance.4 Additionally, it has been shown that dermatology residents who were interested in academic careers at the time of application to the program often lost interest during residency.10

Because it can be difficult to determine a resident’s true interest in an academic career at the time of application and his/her initial interest may wean during residency, it may be more helpful to encourage dermatology residency programs to create environments that will produce residents who are more enthusiastic about and more likely to pursue careers in academia. A lack of mentorship has been shown to be associated with a loss of interest in academic careers during residency.10 If better mentorship opportunities were provided, then perhaps dermatology residents would be more likely to pursue careers in teaching and research.

A 2006 study by Wu et al5 demonstrated that various program characteristics were associated with the pursuit of academic careers among dermatology residents. The number of faculty members and the number of full-time faculty publications at a given residency program were most strongly correlated with the number of residents who pursued academic careers, which suggested that having a large faculty and encouraging dermatology residents to publish research during residency may motivate their pursuit of academic careers in dermatology.5 The current study was designed to replicate these data and respond to limitations in the original study.

Methods

Data were collected from all accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States as of December 31, 2008. The names of all full-time faculty members at these resident programs were obtained, and it was determined where each faculty member attended dermatology residency. The number of graduates who became full-time clinical or research faculty members and the number of graduates who became chairs or chiefs were counted. Residency programs excluded from these analyses included The University of Texas at Austin, University of Texas Medical Branch, and University of Connecticut, which commenced in 2008, as well as Kaiser Permanente Southern California, which commenced in 2010. Residency programs that were started after 2004 were excluded from the study, as it was thought that these programs may not have graduated a sufficient number of residents for assessment. Military residency programs also were excluded, as graduates from these programs often do not freely choose their careers after residency, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) dermatology residency program was excluded because it is not a traditional 3-year residency program.

The primary end point was the ratio of full-time faculty members graduated to the total number of graduates from each dermatology residency program. Based on a prior study by Wu et al5 in 2006, it was believed that several program variables might affect pursuit of academic careers among dermatology residents, including total number of full-time faculty members, total number of residents, NIH funding received (in dollars) in 2008 (http://www.report.nih.gov/award/index.cfm), Dermatology Foundation (DF) funding received (in dollars) in 2008 (http://www.dermatology foundation.org/rap/), number of publications from full-time faculty members in 2008 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), number of full-time faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2008 (American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the American Society of Dermatopathology, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery), number of faculty members on the editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals (Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Archives of Dermatology [currently known as JAMA Dermatology], Dermatologic Surgery, Pediatric Dermatology, and Journal of Cutaneous Pathology), and status as a department of dermatology or a division of internal medicine. The association between the ratio of number of full-time faculty members to number of residents for each residency program were determined for each of the outcome variables because they were believed to serve as an indicator of mentorship.

Data regarding faculty and residents were obtained from program Web sites and inquiries from individual programs. The year 1974 was used as a cutoff for the total number of graduates from each program. For faculty members who split time between 2 residency programs, each program was given credit for the duration of time spent at that program. If it was not clear how long the faculty member spent at each program, a credit of 1.5 years was given, which is half the duration of a dermatology residency. Faculty members who held a PhD only and those who completed their residencies in non-US dermatology residency programs were excluded from the outcome variables. To avoid duplicate faculty publications, collections for each residency program were created within PubMed (ie, if 2 authors from the same program coauthored an article, it was only counted once toward the total number of faculty publications from that program).

Descriptive exploratory statistical analysis in the form of a correlation matrix was completed to determine the most strongly positive and negative variables that were correlated with the ratio of graduating full-time faculty to estimated total graduates. Variables also were correlated with the secondary outcomes of ratio of graduating department chairs/chiefs to estimated total number of graduates and ratio of graduating program directors to estimated total number of graduates. Spearman rank correlation coefficients and P values were reported. Additionally, a 2-sample t test was performed to compare primary and secondary outcome variables between dermatology department versus division of dermatology under the department of internal medicine. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2. The institutional review board at Kaiser Permanente Southern California approved this study.

Results

Due to space considerations, analyses are based on data that are not published in this article. Data regarding the characteristics of each residency program are available from the authors.

Data from 103 dermatology residency programs were included in the analysis. Of these programs, 43% had received NIH funding in 2008 and 22% had received DF funding. Two-thirds of programs had at least 1 faculty member on the editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals; 38% had at least 2 faculty members and 9% had at least 5 faculty members on editorial boards. One-third of programs had no faculty members on these editorial boards. Sixty-nine percent of programs had 1 or more lectures given by full-time faculty members at annual society meetings in 2008; 48% of these programs had 1 to 5 lectures, 17% had 6 to 10, and 5% had more than 10. Thirty-one percent had no faculty members lecture at these meetings. Ninety-six percent of programs had 1 or more publications from full-time faculty members in 2008; 54% of programs had 1 to 20 publications, 24% had 21 to 40 publications, 14% had 41 to 60 publications, 5% had 61 to 80 publications, and 3% had more than 81 publications. Four percent of programs had no publications. Seventy-seven percent of programs were classified as departments and 23% were classified as divisions.

Factors Correlated With Producing Full-time Faculty

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient and P value were reported for each variable (Table 1). All coefficients were positive, signifying a positive correlation. Values closer to 1 were indicative of stronger correlations. P<.05 indicated statistically significant correlations for all factors investigated. The most strongly correlated factor was the ratio of faculty to residents in 2008, followed by number of full-time faculty, number of full-time faculty publications, number of lectures from full-time faculty, and number of faculty on editorial boards. The amount of NIH and DF funding received as well as total number of residents in 2008 also were correlated.

A 2-sample t test was performed to compare the number of graduates pursuing careers in academia from departments versus divisions, but the results were not statistically significant (P=.92).

Ranking Individual Programs With the Highest Number of Graduates Pursuing Academic Careers

The top 5 dermatology residency programs with the highest ratio of full-time faculty members graduated to the estimated total number of graduates were Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), Loyola University (Chicago, Illinois), UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Camden (Camden, New Jersey), Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts), and the University of Vermont (Burlington, Vermont)(Table 2). If faculty members spent time at more than one residency program, they were given credit for time spent at each program. For this reason, not all numbers are integers.

Ranking Individual Programs With the Highest Number of Full-time Faculty Members Who Completed Residency at the Same Institution

The top 10 institutions with the highest percentage of full-time faculty members who completed their residency at the same institution are shown in Table 3. Most of the programs with higher percentages are small programs. Fourteen programs had no faculty members who completed residency at the same program (data not shown).

Comment

Although this study focused on US dermatology residency programs, a shortage of academic dermatologists has been noted worldwide.11-13 By determining residency program variables associated with the pursuit of academic careers, individual programs may be able to make changes that would encourage residents to pursue careers in academia following graduation.

The factor most strongly correlated with graduates pursuing a career in academics was the ratio of faculty to residents in 2008. Also highly correlated was total number of full-time faculty members. We hypothesize that programs with more faculty members may provide better mentorship for residents. A study by Reck et al10 demonstrated that a lack of mentorship was associated with residents’ loss of interest in academics. A survey of residency program directors demonstrated that mentorship played a role in career development and that it was important for residents to have mentors.14 Given the shortage of academic faculty, increasing the number of faculty may not be feasible for individual programs; however, assuming that more faculty members is a marker for mentorship, there are many ways that individual programs may improve mentorship. There are ample opportunities in clinics to demonstrate to residents the value of research to patient care.13 Residency programs also could establish mentorship programs, pairing residents with individual faculty members who share similar interests. Some programs currently have such mentorship programs but many do not.

Also strongly correlated with the number of graduates pursuing careers in academia was the number of full-time faculty publications. It is presumed that these programs also have published extensively in the past, which may have positively influenced the programs’ residents toward academics. This factor can be easily addressed among individual residency programs, and in fact many residency programs do encourage or require residents to publish during their residency. Exposure to the process of collecting data and writing manuscripts can bolster a resident’s interest in academics. In a prior study by Wu et al,5 publications were counted multiple times if multiple faculty members were authors. This limitation was addressed by only counting each manuscript once.

Other variables correlated with the number of graduates pursuing academic careers included number of lectures from full-time faculty members at annual society meetings, number of full-time faculty on editorial boards, and amount of NIH and DF funding received. All of these variables represent the importance of establishing an academic environment and promoting dermatology research. A 2009 study by Lim and Kimball,15 which also evaluated factors associated with pursuing a career in academics, demonstrated that the number of publications prior to residency and volunteerism were associated with an academic career choice. Residents with an MD/PhD were more likely to pursue a career in academics, which also was demonstrated by a similar study in 2008.16

Wu et al5 demonstrated similar results using data from 2001 to 2004; however, amount of NIH and DF funding received was found to be negatively correlated with graduates pursuing a career in academics in the original study. This finding was surprising but was not replicated in the current study. In the current study, the amount of funding (in dollars) rather than number of grants was analyzed because it was felt that the amount of funding received was a better reflection of the quantity of research being conducted. The prior study examined the relationship between the number of grants received and the number of graduates pursuing a career in academics. It is unclear why results varied in the 2 studies, but the most recent data are consistent with our hypothesis that increased research funding is associated with more residents pursuing careers in academia.

The current study also has some limitations. It is a retrospective observational study looking at data from 2008. Choosing data from another study period may have provided different results; however, it is reassuring that the data from the current study were very similar to a prior study looking at data from 2001 to 2004.5

It is assumed that residency program characteristics remained constant over time. It was also assumed that the number of residents in a program remained constant over time. These assumptions were necessary to draw conclusions about the data. It may be that some programs have changed substantially over time, which was not accounted for in the current study. To estimate the total number of graduates, it was assumed that faculty did not practice for more than 35 years, which may not have been true; if the faculty member practiced more than 35 years, it would have altered our estimates. It is also assumed that data on residency programs’ Web sites at time of data collection were updated and accurate. It is likely that data were not 100% accurate on all Web sites at the time of data collection. However, verification of accuracy of data would have been cumbersome, and it would have been difficult to get participation from all programs.

This study does not differentiate the total number of new faculty members who join a residency program and those who are retained for many years. Encouraging residents to pursue a career in academics may increase the number of academic faculty.17 However, efforts must also be placed on retention of faculty members because many of the newly graduated residents who enter academics ultimately leave.18,19

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data suggest that programs with more faculty members may encourage residents to enter careers in academia following graduation. Additionally, the number of publications increases the likelihood of residents pursuing academic careers. By providing mentorship and research opportunities to residents, perhaps residency programs can encourage their graduates to become academic dermatologists. A program’s overall academic environment, including faculty lectures at annual society meetings, faculty on editorial boards, and increased research funding are all associated with graduates pursuing careers in academics.

Ackowledgements—We thank all of the program coordinators, full-time faculty members, program directors, chairs, and chiefs who were kind enough to field our questions if we had any missing data about their programs. We would like to thank Mary H. Black, PhD (Los Angeles, California), for her contribution to the analytical plan.

APPENDIX

Dermatology has become one of the most competitive, if not the most competitive, medical specialties to enter. It attracts the brightest and most accomplished medical students who have excelled not only in the classroom and clinical setting but also in the research setting. Many successful applicants take a substantial amount of time off to pursue research and publish articles.

Despite the competitive nature of the specialty, it is well known that a marked shortage of academic dermatologists has existed for more than 30 years.1-3 In fact, the number of graduates from US dermatology residency programs who pursue academic careers has progressively declined.4 Nearly all dermatology residents have a strong academic background; however, many residents opt to pursue private practice instead of a career in academia.5-9 This trend has implications not only for future dermatology research but also for the teaching and training of future generations of dermatologists.8

To address this shortage, it is important to recruit dermatology residents who have a genuine interest in pursuing academic careers. Unfortunately, many residency applicants may overinflate their interest in academics to boost their chances of acceptance.4 Additionally, it has been shown that dermatology residents who were interested in academic careers at the time of application to the program often lost interest during residency.10

Because it can be difficult to determine a resident’s true interest in an academic career at the time of application and his/her initial interest may wean during residency, it may be more helpful to encourage dermatology residency programs to create environments that will produce residents who are more enthusiastic about and more likely to pursue careers in academia. A lack of mentorship has been shown to be associated with a loss of interest in academic careers during residency.10 If better mentorship opportunities were provided, then perhaps dermatology residents would be more likely to pursue careers in teaching and research.

A 2006 study by Wu et al5 demonstrated that various program characteristics were associated with the pursuit of academic careers among dermatology residents. The number of faculty members and the number of full-time faculty publications at a given residency program were most strongly correlated with the number of residents who pursued academic careers, which suggested that having a large faculty and encouraging dermatology residents to publish research during residency may motivate their pursuit of academic careers in dermatology.5 The current study was designed to replicate these data and respond to limitations in the original study.

Methods

Data were collected from all accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States as of December 31, 2008. The names of all full-time faculty members at these resident programs were obtained, and it was determined where each faculty member attended dermatology residency. The number of graduates who became full-time clinical or research faculty members and the number of graduates who became chairs or chiefs were counted. Residency programs excluded from these analyses included The University of Texas at Austin, University of Texas Medical Branch, and University of Connecticut, which commenced in 2008, as well as Kaiser Permanente Southern California, which commenced in 2010. Residency programs that were started after 2004 were excluded from the study, as it was thought that these programs may not have graduated a sufficient number of residents for assessment. Military residency programs also were excluded, as graduates from these programs often do not freely choose their careers after residency, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) dermatology residency program was excluded because it is not a traditional 3-year residency program.

The primary end point was the ratio of full-time faculty members graduated to the total number of graduates from each dermatology residency program. Based on a prior study by Wu et al5 in 2006, it was believed that several program variables might affect pursuit of academic careers among dermatology residents, including total number of full-time faculty members, total number of residents, NIH funding received (in dollars) in 2008 (http://www.report.nih.gov/award/index.cfm), Dermatology Foundation (DF) funding received (in dollars) in 2008 (http://www.dermatology foundation.org/rap/), number of publications from full-time faculty members in 2008 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), number of full-time faculty lectures given at annual meetings of 5 societies in 2008 (American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the American Society of Dermatopathology, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery), number of faculty members on the editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals (Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Archives of Dermatology [currently known as JAMA Dermatology], Dermatologic Surgery, Pediatric Dermatology, and Journal of Cutaneous Pathology), and status as a department of dermatology or a division of internal medicine. The association between the ratio of number of full-time faculty members to number of residents for each residency program were determined for each of the outcome variables because they were believed to serve as an indicator of mentorship.

Data regarding faculty and residents were obtained from program Web sites and inquiries from individual programs. The year 1974 was used as a cutoff for the total number of graduates from each program. For faculty members who split time between 2 residency programs, each program was given credit for the duration of time spent at that program. If it was not clear how long the faculty member spent at each program, a credit of 1.5 years was given, which is half the duration of a dermatology residency. Faculty members who held a PhD only and those who completed their residencies in non-US dermatology residency programs were excluded from the outcome variables. To avoid duplicate faculty publications, collections for each residency program were created within PubMed (ie, if 2 authors from the same program coauthored an article, it was only counted once toward the total number of faculty publications from that program).

Descriptive exploratory statistical analysis in the form of a correlation matrix was completed to determine the most strongly positive and negative variables that were correlated with the ratio of graduating full-time faculty to estimated total graduates. Variables also were correlated with the secondary outcomes of ratio of graduating department chairs/chiefs to estimated total number of graduates and ratio of graduating program directors to estimated total number of graduates. Spearman rank correlation coefficients and P values were reported. Additionally, a 2-sample t test was performed to compare primary and secondary outcome variables between dermatology department versus division of dermatology under the department of internal medicine. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2. The institutional review board at Kaiser Permanente Southern California approved this study.

Results

Due to space considerations, analyses are based on data that are not published in this article. Data regarding the characteristics of each residency program are available from the authors.

Data from 103 dermatology residency programs were included in the analysis. Of these programs, 43% had received NIH funding in 2008 and 22% had received DF funding. Two-thirds of programs had at least 1 faculty member on the editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals; 38% had at least 2 faculty members and 9% had at least 5 faculty members on editorial boards. One-third of programs had no faculty members on these editorial boards. Sixty-nine percent of programs had 1 or more lectures given by full-time faculty members at annual society meetings in 2008; 48% of these programs had 1 to 5 lectures, 17% had 6 to 10, and 5% had more than 10. Thirty-one percent had no faculty members lecture at these meetings. Ninety-six percent of programs had 1 or more publications from full-time faculty members in 2008; 54% of programs had 1 to 20 publications, 24% had 21 to 40 publications, 14% had 41 to 60 publications, 5% had 61 to 80 publications, and 3% had more than 81 publications. Four percent of programs had no publications. Seventy-seven percent of programs were classified as departments and 23% were classified as divisions.

Factors Correlated With Producing Full-time Faculty

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient and P value were reported for each variable (Table 1). All coefficients were positive, signifying a positive correlation. Values closer to 1 were indicative of stronger correlations. P<.05 indicated statistically significant correlations for all factors investigated. The most strongly correlated factor was the ratio of faculty to residents in 2008, followed by number of full-time faculty, number of full-time faculty publications, number of lectures from full-time faculty, and number of faculty on editorial boards. The amount of NIH and DF funding received as well as total number of residents in 2008 also were correlated.

A 2-sample t test was performed to compare the number of graduates pursuing careers in academia from departments versus divisions, but the results were not statistically significant (P=.92).

Ranking Individual Programs With the Highest Number of Graduates Pursuing Academic Careers

The top 5 dermatology residency programs with the highest ratio of full-time faculty members graduated to the estimated total number of graduates were Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), Loyola University (Chicago, Illinois), UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Camden (Camden, New Jersey), Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts), and the University of Vermont (Burlington, Vermont)(Table 2). If faculty members spent time at more than one residency program, they were given credit for time spent at each program. For this reason, not all numbers are integers.

Ranking Individual Programs With the Highest Number of Full-time Faculty Members Who Completed Residency at the Same Institution

The top 10 institutions with the highest percentage of full-time faculty members who completed their residency at the same institution are shown in Table 3. Most of the programs with higher percentages are small programs. Fourteen programs had no faculty members who completed residency at the same program (data not shown).

Comment

Although this study focused on US dermatology residency programs, a shortage of academic dermatologists has been noted worldwide.11-13 By determining residency program variables associated with the pursuit of academic careers, individual programs may be able to make changes that would encourage residents to pursue careers in academia following graduation.

The factor most strongly correlated with graduates pursuing a career in academics was the ratio of faculty to residents in 2008. Also highly correlated was total number of full-time faculty members. We hypothesize that programs with more faculty members may provide better mentorship for residents. A study by Reck et al10 demonstrated that a lack of mentorship was associated with residents’ loss of interest in academics. A survey of residency program directors demonstrated that mentorship played a role in career development and that it was important for residents to have mentors.14 Given the shortage of academic faculty, increasing the number of faculty may not be feasible for individual programs; however, assuming that more faculty members is a marker for mentorship, there are many ways that individual programs may improve mentorship. There are ample opportunities in clinics to demonstrate to residents the value of research to patient care.13 Residency programs also could establish mentorship programs, pairing residents with individual faculty members who share similar interests. Some programs currently have such mentorship programs but many do not.

Also strongly correlated with the number of graduates pursuing careers in academia was the number of full-time faculty publications. It is presumed that these programs also have published extensively in the past, which may have positively influenced the programs’ residents toward academics. This factor can be easily addressed among individual residency programs, and in fact many residency programs do encourage or require residents to publish during their residency. Exposure to the process of collecting data and writing manuscripts can bolster a resident’s interest in academics. In a prior study by Wu et al,5 publications were counted multiple times if multiple faculty members were authors. This limitation was addressed by only counting each manuscript once.

Other variables correlated with the number of graduates pursuing academic careers included number of lectures from full-time faculty members at annual society meetings, number of full-time faculty on editorial boards, and amount of NIH and DF funding received. All of these variables represent the importance of establishing an academic environment and promoting dermatology research. A 2009 study by Lim and Kimball,15 which also evaluated factors associated with pursuing a career in academics, demonstrated that the number of publications prior to residency and volunteerism were associated with an academic career choice. Residents with an MD/PhD were more likely to pursue a career in academics, which also was demonstrated by a similar study in 2008.16

Wu et al5 demonstrated similar results using data from 2001 to 2004; however, amount of NIH and DF funding received was found to be negatively correlated with graduates pursuing a career in academics in the original study. This finding was surprising but was not replicated in the current study. In the current study, the amount of funding (in dollars) rather than number of grants was analyzed because it was felt that the amount of funding received was a better reflection of the quantity of research being conducted. The prior study examined the relationship between the number of grants received and the number of graduates pursuing a career in academics. It is unclear why results varied in the 2 studies, but the most recent data are consistent with our hypothesis that increased research funding is associated with more residents pursuing careers in academia.

The current study also has some limitations. It is a retrospective observational study looking at data from 2008. Choosing data from another study period may have provided different results; however, it is reassuring that the data from the current study were very similar to a prior study looking at data from 2001 to 2004.5

It is assumed that residency program characteristics remained constant over time. It was also assumed that the number of residents in a program remained constant over time. These assumptions were necessary to draw conclusions about the data. It may be that some programs have changed substantially over time, which was not accounted for in the current study. To estimate the total number of graduates, it was assumed that faculty did not practice for more than 35 years, which may not have been true; if the faculty member practiced more than 35 years, it would have altered our estimates. It is also assumed that data on residency programs’ Web sites at time of data collection were updated and accurate. It is likely that data were not 100% accurate on all Web sites at the time of data collection. However, verification of accuracy of data would have been cumbersome, and it would have been difficult to get participation from all programs.

This study does not differentiate the total number of new faculty members who join a residency program and those who are retained for many years. Encouraging residents to pursue a career in academics may increase the number of academic faculty.17 However, efforts must also be placed on retention of faculty members because many of the newly graduated residents who enter academics ultimately leave.18,19

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data suggest that programs with more faculty members may encourage residents to enter careers in academia following graduation. Additionally, the number of publications increases the likelihood of residents pursuing academic careers. By providing mentorship and research opportunities to residents, perhaps residency programs can encourage their graduates to become academic dermatologists. A program’s overall academic environment, including faculty lectures at annual society meetings, faculty on editorial boards, and increased research funding are all associated with graduates pursuing careers in academics.

Ackowledgements—We thank all of the program coordinators, full-time faculty members, program directors, chairs, and chiefs who were kind enough to field our questions if we had any missing data about their programs. We would like to thank Mary H. Black, PhD (Los Angeles, California), for her contribution to the analytical plan.

APPENDIX

1. Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, Lynch PJ, et al. Shortage of full-time faculty in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:529-532.

2. Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, Caro I. Shortage of full-time faculty in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:297-301.

3. Resneck J. Too few or too many academic dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

4. Kia KF, Gielczyk RA, Ellis CN. Academia is the life for me, I’m sure. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:911-913.

5. Wu JJ, Ramirez CC, Alonso CA, et al. Dermatology residency program characteristics that correlate with graduates selecting an academic dermatology career. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:845-850.

6. Wu JJ, Tyring SK. The academic strength of current dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:22.

7. Hinchman KF, Wu JJ. Decisions in choosing a career in academic dermatology. Cutis. 2008;82:368-371.

8. Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

9. Rubenstein DS, Blauvelt A, Chen SC, et al. The future of academic dermatology in the United States: report on the resident retreat for future physician-scientists, June 15-17, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:300-303.

10. Reck SJ, Stratman EJ, Vogel C, et al. Assessment of residents’ loss of interest in academic careers and identification of correctable factors. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:855-858.

11. Olerud JE. Academic workforce in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:409-410.

12. Singer N. More doctors turning to the business of beauty. New York Times. November 30, 2006:A1.

13. Dogra S. Fate of medical dermatology in the era of cosmetic dermatology and dermatosurgery. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:4-7.

14. Donovan JC. A survey of dermatology residency program directors’ views on mentorship. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

15. Lim JL, Kimball AB. Residency applications and identification of factors associated with residents’ ultimate career decisions. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:943-944.

16. Wu JJ, Davis KF, Ramirez CC, et al. MD/PhDs are more likely than MDs to choose a career in academics. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:27.

17. Wu JJ. Current strategies to address the ongoing shortage of academic dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1065-1066.

18. Loo DS, Liu CL, Geller AC, et al. Academic dermatology manpower. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:341-347.

19. Turner E, Yoo J, Salter S, et al. Leadership workforce in academic dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:948-949.

1. Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, Lynch PJ, et al. Shortage of full-time faculty in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:529-532.

2. Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, Caro I. Shortage of full-time faculty in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:297-301.

3. Resneck J. Too few or too many academic dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

4. Kia KF, Gielczyk RA, Ellis CN. Academia is the life for me, I’m sure. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:911-913.

5. Wu JJ, Ramirez CC, Alonso CA, et al. Dermatology residency program characteristics that correlate with graduates selecting an academic dermatology career. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:845-850.

6. Wu JJ, Tyring SK. The academic strength of current dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:22.

7. Hinchman KF, Wu JJ. Decisions in choosing a career in academic dermatology. Cutis. 2008;82:368-371.

8. Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

9. Rubenstein DS, Blauvelt A, Chen SC, et al. The future of academic dermatology in the United States: report on the resident retreat for future physician-scientists, June 15-17, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:300-303.

10. Reck SJ, Stratman EJ, Vogel C, et al. Assessment of residents’ loss of interest in academic careers and identification of correctable factors. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:855-858.

11. Olerud JE. Academic workforce in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:409-410.

12. Singer N. More doctors turning to the business of beauty. New York Times. November 30, 2006:A1.

13. Dogra S. Fate of medical dermatology in the era of cosmetic dermatology and dermatosurgery. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:4-7.

14. Donovan JC. A survey of dermatology residency program directors’ views on mentorship. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

15. Lim JL, Kimball AB. Residency applications and identification of factors associated with residents’ ultimate career decisions. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:943-944.

16. Wu JJ, Davis KF, Ramirez CC, et al. MD/PhDs are more likely than MDs to choose a career in academics. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:27.

17. Wu JJ. Current strategies to address the ongoing shortage of academic dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1065-1066.

18. Loo DS, Liu CL, Geller AC, et al. Academic dermatology manpower. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:341-347.

19. Turner E, Yoo J, Salter S, et al. Leadership workforce in academic dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:948-949.

Practice Points

- Because of the shortage of academic dermatologists, dermatology residency programs may wish to create an environment that will produce residents who are more likely to pursue careers in academia.

- Dermatology residency programs with more faculty members may encourage residents to enter careers in academia following graduation.