User login

Amid recent reports of hackers targeting and blackmailing health care systems and even patients, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies have issued warning of “imminent” cyberattacks on more U.S. hospitals.

A new report released by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, part of the Department of Homeland Security, noted that the FBI and the Department of Health & Human Services have “credible information of an increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and health care providers.”

The agencies are urging “timely and reasonable precautions” to protect health care networks from these threats.

As reported, hackers accessed patient records at Vastaamo, Finland’s largest private psychotherapy system, and emailed some patients last month demanding €200 in bitcoin or else personal health data would be released online.

In June, the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an information technology (IT) “security incident” that led to the payout of $1.14 million to individuals responsible for a malware attack in exchange for the return of data.

In addition, last week, Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, Ore., released a statement in which it said there had been a ransomware attack on its computer systems. Although “there is no evidence that patient information has been compromised,” some of its systems are still down.

“We’re open for business, it’s just not business as usual,” Tom Hottman, public information officer at Sky Lakes, said in an interview.

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview, “People have known for a long time that there are nefarious actors out there.” He said all health care systems should be prepared to deal with these problems.

“In the face of a warning from the FBI, I’d say that’s even more important now,” Dr. Appelbaum added.

‘Malicious cyber actors’

In the new CISA report, the agency noted that it, the FBI, and the HHS have been assessing “malicious cyber actors” targeting health care systems with malware loaders such as TrickBot and BazarLoader, which often lead to data theft, ransomware attacks, and service disruptions.

“The cybercriminal enterprise behind TrickBot, which is likely also the creator of BazarLoader malware, has continued to develop new functionality and tools, increasing the ease, speed, and profitability of victimization,” the report authors wrote.

Phishing campaigns often contain attachments with malware or links to malicious websites. “Loaders start the infection chain by distributing the payload,” the report noted. A backdoor mechanism is then installed on the victim’s device.

In addition to TrickBot and BazarLoader (or BazarBackdoor), the report discussed other malicious tools, including Ryuk and Conti, which are types of ransomware that can infect systems for hackers’ financial gain.

“These issues will be particularly challenging for organizations within the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, administrators will need to balance this risk when determining their cybersecurity investments,” the agencies wrote.

Dr. Appelbaum said his organization is taking the warning seriously.

“When the report first came out, I received emails from every system that I’m affiliated with warning about it and encouraging me as a member of the medical staff to take the usual prudent precautions,” such as not opening attachments or links from unknown sources, he said.

“The FBI warning has what seems like very reasonable advice, which is that every system should automatically back up their data off site in a separate system that’s differently accessible,” he added.

After a ransomware attack, the most recently entered information may not be backed up and could get lost, but “that’s a lot easier to deal with then losing access to all of your medical records,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

Ipsit Vahia, MD, medical director at the Institute for Technology and Psychiatry at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., noted that, in answer to the FBI warning, he has heard that many centers, including his own, are warning their clinicians not to open any email attachments at this time.

Recent attacks

UCSF issued a statement noting that malware detected in early June led to the encryption of “a limited number of servers” in its medical school, making them temporarily inaccessible.

“We do not currently believe patient medical records were exposed,” the university said in the statement.

It added that because the encrypted data were necessary for “some of the academic work” conducted at UCSF, they agreed to pay a portion of the ransom demand – about $1.14 million. The hackers then provided a tool that unlocked the encrypted data.

“We continue to cooperate with law enforcement and we appreciate everyone’s understanding that we are limited in what we can share while we continue our investigation,” the statement reads. UCSF declined a request for further comment.

At Sky Lakes Medical Center, computer systems are still down after its ransomware attack, including use of electronic medical records, but the Oregon-based health care system is still seeing patients.

They are “being interviewed old school,” with the admitting process being conducted on paper, “but patient care goes on,” said Mr. Hottman.

In addition to a teaching hospital, Sky Lakes comprises specialty and primary care clinics, including a cancer treatment center. All remain open to patients at this time.

Diagnostic imaging is also continuing, but “getting the image to a place it can be read” has become more complicated, said Mr. Hottman.

“We have some work-arounds in process, and a plan is being assembled that we think will be in place as early as this weekend so that we can get those images read starting next week,” he said.

In addition, “scheduling is a little clunky,” he reported. However, “we have an awesome staff with a good attitude, so there’s still a whole lot we can do.”

He also noted that his institution has reconfirmed that, as of Nov. 4, no patient data had been compromised.

‘Especially chilling’

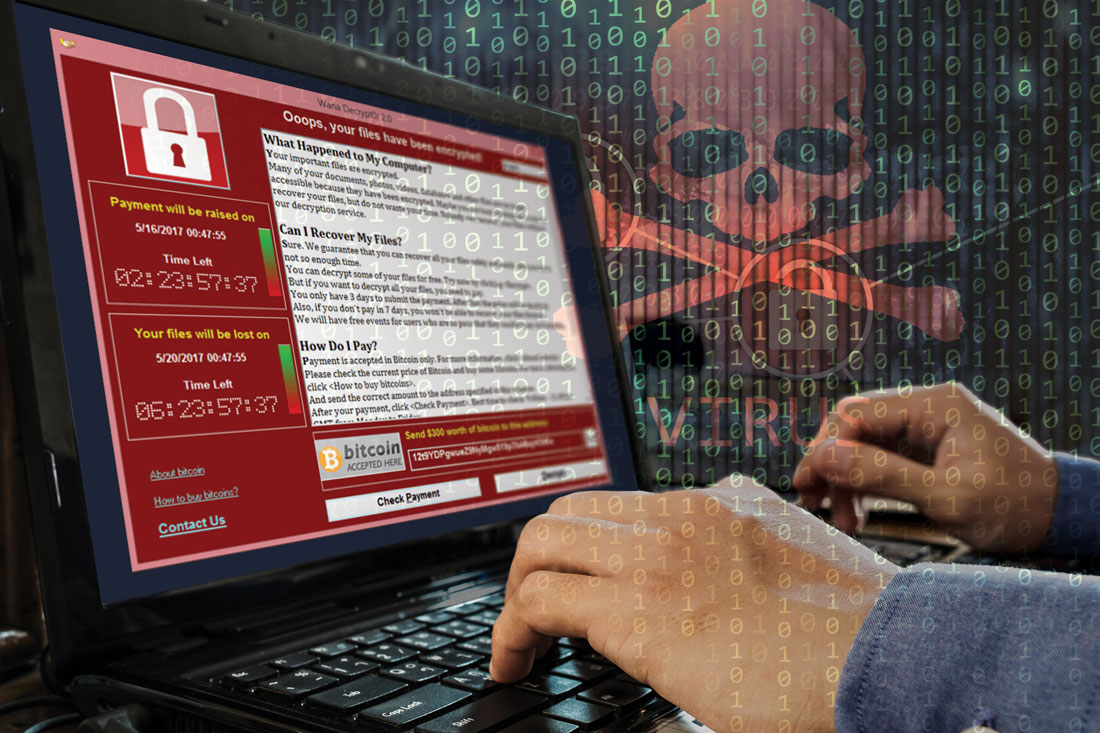

Targeting hospitals through cyberattacks isn’t new. In 2017, the WannaCry virus affected more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries, including the operating system of the U.K. National Health Service. The cyberattack locked clinicians out of NHS patient records and other digital tools for 3 days.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that, as hospital systems become more dependent on the Internet and on electronic communications, they become more vulnerable to data breaches.

“I think it’s clear that there have been concerted efforts lately to undertake attacks on health care IT systems to either hold them hostage, as in a ransomware attack, or to download files and use that information for profit,” he said.

Still, Dr. Vahia noted that contacting patients directly, which occurred in the Finland data breach and blackmail scheme, is something new. It is “especially chilling” that individual psychiatric patients were targeted.

It’s difficult to overstate how big a deal this is, and we should be treating it with the appropriate level of urgency,” he said in an interview.

“It shows how badly things can go wrong when security is compromised; and it should make us take a step back and survey the world of digital health to gain recognition of how much risk there might be that we haven’t really understood before,” Dr. Vahia said.

Clinical tips

Asked whether he had any tips to share with clinicians, Mr. Hottman noted that the best time to have a plan is before something dire happens.

“I would make [the possibility of cyberattacks] part of the emergency preparedness program. What if you don’t have access to computers? What do you do?” It’s important to answer those questions prior to systems going down, he said.

Mr. Hottman reported that after a mechanical failure last year put their computer systems offline for a day, “we started putting all critical information on paper and in a binder,” including phone numbers for the state police.

Dr. Vahia noted that another important step for clinicians “is to just pause and take stock of how digitally dependent” health care is becoming. He also warned that precautions should be taken regarding wearables and apps, as well as for electronic medical records. He noted the importance of strong passwords and two-step verification processes.

Even with the risks, digital technology has had a major impact on health care efficiency. “It’s not perfect, the work is ongoing, and there are big questions that need to be addressed, but in the end, the ability of technology when used right and securely” leads to better patient care, he said.

John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, agreed that digital health care is and will remain very important; but at the same time, security issues need proper attention.

“When you look back at medical hacks that have happened, there’s often a human error behind it. It’s rare for someone to break encryption. I think we have pretty darn good security, but we need to realize that sometimes errors will happen,” he said in an interview.

As an example, Dr. Torous, who is also chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Health and Technology Committee, cited phishing emails, which depend on a user clicking a link that can cause a virus to be downloaded into their network.

“You can be cautious, but it takes just one person to download an attachment with a virus in it” to cause disruptions, Dr. Torous said.

Telehealth implications

After its data breach, Vastaamo posted on its website a notice that video is never recorded during the centers’ telehealth sessions, and so patients need not worry that any videos could be leaked online.

Asked whether video is commonly recorded during telehealth sessions in the United States, Dr. Vahia said that he was not aware of sessions being recorded, especially because the amount of the data would be too great to store indefinitely.

Dr. Appelbaum agreed and said that, to his knowledge, no clinicians at Columbia University are recording telehealth sessions. He said that it would represent a privacy threat, and he noted that most health care providers “don’t have the time to go back and watch videos of their interactions with patients.”

In the case of recordings for research purposes, he emphasized that it would be important to get consent and then store the health information offline.

As for other telehealth security risks, Dr. Vahia noted that it is possible that if a computer or device is compromised, an individual could hack into a camera and observe the session. In addition to microphones, “these pose some especially high vulnerabilities,” he said. “Clinicians need to pay attention as to whether the cameras they’re using for telecare are on or if they’re covered when not in use. And they should pay attention to security settings on smartphones and ensure microphones are not turned on as the default.”

Dr. Appelbaum said the HIPAA requires that telehealth sessions be conducted on secure systems, so clinicians need to ascertain whether the system they’re using complies with that rule.

“Particularly people who are not part of larger systems and would not usually take on that responsibility, maybe they’re in private practice or a small group, they really need to check on the security level and on HIPAA compliance and not just assume that it is adequately secure,” he said.

Dr. Appelbaum, who is also a past president of the APA and director of the Center for Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University, noted that the major risk for hospitals after a cyberattack is probably not liability to individual patients.

“It’s much more likely that they would face fines from HIPAA if it’s found that they failed to live up to HIPAA requirements,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Amid recent reports of hackers targeting and blackmailing health care systems and even patients, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies have issued warning of “imminent” cyberattacks on more U.S. hospitals.

A new report released by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, part of the Department of Homeland Security, noted that the FBI and the Department of Health & Human Services have “credible information of an increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and health care providers.”

The agencies are urging “timely and reasonable precautions” to protect health care networks from these threats.

As reported, hackers accessed patient records at Vastaamo, Finland’s largest private psychotherapy system, and emailed some patients last month demanding €200 in bitcoin or else personal health data would be released online.

In June, the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an information technology (IT) “security incident” that led to the payout of $1.14 million to individuals responsible for a malware attack in exchange for the return of data.

In addition, last week, Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, Ore., released a statement in which it said there had been a ransomware attack on its computer systems. Although “there is no evidence that patient information has been compromised,” some of its systems are still down.

“We’re open for business, it’s just not business as usual,” Tom Hottman, public information officer at Sky Lakes, said in an interview.

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview, “People have known for a long time that there are nefarious actors out there.” He said all health care systems should be prepared to deal with these problems.

“In the face of a warning from the FBI, I’d say that’s even more important now,” Dr. Appelbaum added.

‘Malicious cyber actors’

In the new CISA report, the agency noted that it, the FBI, and the HHS have been assessing “malicious cyber actors” targeting health care systems with malware loaders such as TrickBot and BazarLoader, which often lead to data theft, ransomware attacks, and service disruptions.

“The cybercriminal enterprise behind TrickBot, which is likely also the creator of BazarLoader malware, has continued to develop new functionality and tools, increasing the ease, speed, and profitability of victimization,” the report authors wrote.

Phishing campaigns often contain attachments with malware or links to malicious websites. “Loaders start the infection chain by distributing the payload,” the report noted. A backdoor mechanism is then installed on the victim’s device.

In addition to TrickBot and BazarLoader (or BazarBackdoor), the report discussed other malicious tools, including Ryuk and Conti, which are types of ransomware that can infect systems for hackers’ financial gain.

“These issues will be particularly challenging for organizations within the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, administrators will need to balance this risk when determining their cybersecurity investments,” the agencies wrote.

Dr. Appelbaum said his organization is taking the warning seriously.

“When the report first came out, I received emails from every system that I’m affiliated with warning about it and encouraging me as a member of the medical staff to take the usual prudent precautions,” such as not opening attachments or links from unknown sources, he said.

“The FBI warning has what seems like very reasonable advice, which is that every system should automatically back up their data off site in a separate system that’s differently accessible,” he added.

After a ransomware attack, the most recently entered information may not be backed up and could get lost, but “that’s a lot easier to deal with then losing access to all of your medical records,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

Ipsit Vahia, MD, medical director at the Institute for Technology and Psychiatry at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., noted that, in answer to the FBI warning, he has heard that many centers, including his own, are warning their clinicians not to open any email attachments at this time.

Recent attacks

UCSF issued a statement noting that malware detected in early June led to the encryption of “a limited number of servers” in its medical school, making them temporarily inaccessible.

“We do not currently believe patient medical records were exposed,” the university said in the statement.

It added that because the encrypted data were necessary for “some of the academic work” conducted at UCSF, they agreed to pay a portion of the ransom demand – about $1.14 million. The hackers then provided a tool that unlocked the encrypted data.

“We continue to cooperate with law enforcement and we appreciate everyone’s understanding that we are limited in what we can share while we continue our investigation,” the statement reads. UCSF declined a request for further comment.

At Sky Lakes Medical Center, computer systems are still down after its ransomware attack, including use of electronic medical records, but the Oregon-based health care system is still seeing patients.

They are “being interviewed old school,” with the admitting process being conducted on paper, “but patient care goes on,” said Mr. Hottman.

In addition to a teaching hospital, Sky Lakes comprises specialty and primary care clinics, including a cancer treatment center. All remain open to patients at this time.

Diagnostic imaging is also continuing, but “getting the image to a place it can be read” has become more complicated, said Mr. Hottman.

“We have some work-arounds in process, and a plan is being assembled that we think will be in place as early as this weekend so that we can get those images read starting next week,” he said.

In addition, “scheduling is a little clunky,” he reported. However, “we have an awesome staff with a good attitude, so there’s still a whole lot we can do.”

He also noted that his institution has reconfirmed that, as of Nov. 4, no patient data had been compromised.

‘Especially chilling’

Targeting hospitals through cyberattacks isn’t new. In 2017, the WannaCry virus affected more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries, including the operating system of the U.K. National Health Service. The cyberattack locked clinicians out of NHS patient records and other digital tools for 3 days.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that, as hospital systems become more dependent on the Internet and on electronic communications, they become more vulnerable to data breaches.

“I think it’s clear that there have been concerted efforts lately to undertake attacks on health care IT systems to either hold them hostage, as in a ransomware attack, or to download files and use that information for profit,” he said.

Still, Dr. Vahia noted that contacting patients directly, which occurred in the Finland data breach and blackmail scheme, is something new. It is “especially chilling” that individual psychiatric patients were targeted.

It’s difficult to overstate how big a deal this is, and we should be treating it with the appropriate level of urgency,” he said in an interview.

“It shows how badly things can go wrong when security is compromised; and it should make us take a step back and survey the world of digital health to gain recognition of how much risk there might be that we haven’t really understood before,” Dr. Vahia said.

Clinical tips

Asked whether he had any tips to share with clinicians, Mr. Hottman noted that the best time to have a plan is before something dire happens.

“I would make [the possibility of cyberattacks] part of the emergency preparedness program. What if you don’t have access to computers? What do you do?” It’s important to answer those questions prior to systems going down, he said.

Mr. Hottman reported that after a mechanical failure last year put their computer systems offline for a day, “we started putting all critical information on paper and in a binder,” including phone numbers for the state police.

Dr. Vahia noted that another important step for clinicians “is to just pause and take stock of how digitally dependent” health care is becoming. He also warned that precautions should be taken regarding wearables and apps, as well as for electronic medical records. He noted the importance of strong passwords and two-step verification processes.

Even with the risks, digital technology has had a major impact on health care efficiency. “It’s not perfect, the work is ongoing, and there are big questions that need to be addressed, but in the end, the ability of technology when used right and securely” leads to better patient care, he said.

John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, agreed that digital health care is and will remain very important; but at the same time, security issues need proper attention.

“When you look back at medical hacks that have happened, there’s often a human error behind it. It’s rare for someone to break encryption. I think we have pretty darn good security, but we need to realize that sometimes errors will happen,” he said in an interview.

As an example, Dr. Torous, who is also chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Health and Technology Committee, cited phishing emails, which depend on a user clicking a link that can cause a virus to be downloaded into their network.

“You can be cautious, but it takes just one person to download an attachment with a virus in it” to cause disruptions, Dr. Torous said.

Telehealth implications

After its data breach, Vastaamo posted on its website a notice that video is never recorded during the centers’ telehealth sessions, and so patients need not worry that any videos could be leaked online.

Asked whether video is commonly recorded during telehealth sessions in the United States, Dr. Vahia said that he was not aware of sessions being recorded, especially because the amount of the data would be too great to store indefinitely.

Dr. Appelbaum agreed and said that, to his knowledge, no clinicians at Columbia University are recording telehealth sessions. He said that it would represent a privacy threat, and he noted that most health care providers “don’t have the time to go back and watch videos of their interactions with patients.”

In the case of recordings for research purposes, he emphasized that it would be important to get consent and then store the health information offline.

As for other telehealth security risks, Dr. Vahia noted that it is possible that if a computer or device is compromised, an individual could hack into a camera and observe the session. In addition to microphones, “these pose some especially high vulnerabilities,” he said. “Clinicians need to pay attention as to whether the cameras they’re using for telecare are on or if they’re covered when not in use. And they should pay attention to security settings on smartphones and ensure microphones are not turned on as the default.”

Dr. Appelbaum said the HIPAA requires that telehealth sessions be conducted on secure systems, so clinicians need to ascertain whether the system they’re using complies with that rule.

“Particularly people who are not part of larger systems and would not usually take on that responsibility, maybe they’re in private practice or a small group, they really need to check on the security level and on HIPAA compliance and not just assume that it is adequately secure,” he said.

Dr. Appelbaum, who is also a past president of the APA and director of the Center for Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University, noted that the major risk for hospitals after a cyberattack is probably not liability to individual patients.

“It’s much more likely that they would face fines from HIPAA if it’s found that they failed to live up to HIPAA requirements,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Amid recent reports of hackers targeting and blackmailing health care systems and even patients, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies have issued warning of “imminent” cyberattacks on more U.S. hospitals.

A new report released by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, part of the Department of Homeland Security, noted that the FBI and the Department of Health & Human Services have “credible information of an increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and health care providers.”

The agencies are urging “timely and reasonable precautions” to protect health care networks from these threats.

As reported, hackers accessed patient records at Vastaamo, Finland’s largest private psychotherapy system, and emailed some patients last month demanding €200 in bitcoin or else personal health data would be released online.

In June, the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an information technology (IT) “security incident” that led to the payout of $1.14 million to individuals responsible for a malware attack in exchange for the return of data.

In addition, last week, Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, Ore., released a statement in which it said there had been a ransomware attack on its computer systems. Although “there is no evidence that patient information has been compromised,” some of its systems are still down.

“We’re open for business, it’s just not business as usual,” Tom Hottman, public information officer at Sky Lakes, said in an interview.

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview, “People have known for a long time that there are nefarious actors out there.” He said all health care systems should be prepared to deal with these problems.

“In the face of a warning from the FBI, I’d say that’s even more important now,” Dr. Appelbaum added.

‘Malicious cyber actors’

In the new CISA report, the agency noted that it, the FBI, and the HHS have been assessing “malicious cyber actors” targeting health care systems with malware loaders such as TrickBot and BazarLoader, which often lead to data theft, ransomware attacks, and service disruptions.

“The cybercriminal enterprise behind TrickBot, which is likely also the creator of BazarLoader malware, has continued to develop new functionality and tools, increasing the ease, speed, and profitability of victimization,” the report authors wrote.

Phishing campaigns often contain attachments with malware or links to malicious websites. “Loaders start the infection chain by distributing the payload,” the report noted. A backdoor mechanism is then installed on the victim’s device.

In addition to TrickBot and BazarLoader (or BazarBackdoor), the report discussed other malicious tools, including Ryuk and Conti, which are types of ransomware that can infect systems for hackers’ financial gain.

“These issues will be particularly challenging for organizations within the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, administrators will need to balance this risk when determining their cybersecurity investments,” the agencies wrote.

Dr. Appelbaum said his organization is taking the warning seriously.

“When the report first came out, I received emails from every system that I’m affiliated with warning about it and encouraging me as a member of the medical staff to take the usual prudent precautions,” such as not opening attachments or links from unknown sources, he said.

“The FBI warning has what seems like very reasonable advice, which is that every system should automatically back up their data off site in a separate system that’s differently accessible,” he added.

After a ransomware attack, the most recently entered information may not be backed up and could get lost, but “that’s a lot easier to deal with then losing access to all of your medical records,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

Ipsit Vahia, MD, medical director at the Institute for Technology and Psychiatry at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., noted that, in answer to the FBI warning, he has heard that many centers, including his own, are warning their clinicians not to open any email attachments at this time.

Recent attacks

UCSF issued a statement noting that malware detected in early June led to the encryption of “a limited number of servers” in its medical school, making them temporarily inaccessible.

“We do not currently believe patient medical records were exposed,” the university said in the statement.

It added that because the encrypted data were necessary for “some of the academic work” conducted at UCSF, they agreed to pay a portion of the ransom demand – about $1.14 million. The hackers then provided a tool that unlocked the encrypted data.

“We continue to cooperate with law enforcement and we appreciate everyone’s understanding that we are limited in what we can share while we continue our investigation,” the statement reads. UCSF declined a request for further comment.

At Sky Lakes Medical Center, computer systems are still down after its ransomware attack, including use of electronic medical records, but the Oregon-based health care system is still seeing patients.

They are “being interviewed old school,” with the admitting process being conducted on paper, “but patient care goes on,” said Mr. Hottman.

In addition to a teaching hospital, Sky Lakes comprises specialty and primary care clinics, including a cancer treatment center. All remain open to patients at this time.

Diagnostic imaging is also continuing, but “getting the image to a place it can be read” has become more complicated, said Mr. Hottman.

“We have some work-arounds in process, and a plan is being assembled that we think will be in place as early as this weekend so that we can get those images read starting next week,” he said.

In addition, “scheduling is a little clunky,” he reported. However, “we have an awesome staff with a good attitude, so there’s still a whole lot we can do.”

He also noted that his institution has reconfirmed that, as of Nov. 4, no patient data had been compromised.

‘Especially chilling’

Targeting hospitals through cyberattacks isn’t new. In 2017, the WannaCry virus affected more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries, including the operating system of the U.K. National Health Service. The cyberattack locked clinicians out of NHS patient records and other digital tools for 3 days.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that, as hospital systems become more dependent on the Internet and on electronic communications, they become more vulnerable to data breaches.

“I think it’s clear that there have been concerted efforts lately to undertake attacks on health care IT systems to either hold them hostage, as in a ransomware attack, or to download files and use that information for profit,” he said.

Still, Dr. Vahia noted that contacting patients directly, which occurred in the Finland data breach and blackmail scheme, is something new. It is “especially chilling” that individual psychiatric patients were targeted.

It’s difficult to overstate how big a deal this is, and we should be treating it with the appropriate level of urgency,” he said in an interview.

“It shows how badly things can go wrong when security is compromised; and it should make us take a step back and survey the world of digital health to gain recognition of how much risk there might be that we haven’t really understood before,” Dr. Vahia said.

Clinical tips

Asked whether he had any tips to share with clinicians, Mr. Hottman noted that the best time to have a plan is before something dire happens.

“I would make [the possibility of cyberattacks] part of the emergency preparedness program. What if you don’t have access to computers? What do you do?” It’s important to answer those questions prior to systems going down, he said.

Mr. Hottman reported that after a mechanical failure last year put their computer systems offline for a day, “we started putting all critical information on paper and in a binder,” including phone numbers for the state police.

Dr. Vahia noted that another important step for clinicians “is to just pause and take stock of how digitally dependent” health care is becoming. He also warned that precautions should be taken regarding wearables and apps, as well as for electronic medical records. He noted the importance of strong passwords and two-step verification processes.

Even with the risks, digital technology has had a major impact on health care efficiency. “It’s not perfect, the work is ongoing, and there are big questions that need to be addressed, but in the end, the ability of technology when used right and securely” leads to better patient care, he said.

John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, agreed that digital health care is and will remain very important; but at the same time, security issues need proper attention.

“When you look back at medical hacks that have happened, there’s often a human error behind it. It’s rare for someone to break encryption. I think we have pretty darn good security, but we need to realize that sometimes errors will happen,” he said in an interview.

As an example, Dr. Torous, who is also chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Health and Technology Committee, cited phishing emails, which depend on a user clicking a link that can cause a virus to be downloaded into their network.

“You can be cautious, but it takes just one person to download an attachment with a virus in it” to cause disruptions, Dr. Torous said.

Telehealth implications

After its data breach, Vastaamo posted on its website a notice that video is never recorded during the centers’ telehealth sessions, and so patients need not worry that any videos could be leaked online.

Asked whether video is commonly recorded during telehealth sessions in the United States, Dr. Vahia said that he was not aware of sessions being recorded, especially because the amount of the data would be too great to store indefinitely.

Dr. Appelbaum agreed and said that, to his knowledge, no clinicians at Columbia University are recording telehealth sessions. He said that it would represent a privacy threat, and he noted that most health care providers “don’t have the time to go back and watch videos of their interactions with patients.”

In the case of recordings for research purposes, he emphasized that it would be important to get consent and then store the health information offline.

As for other telehealth security risks, Dr. Vahia noted that it is possible that if a computer or device is compromised, an individual could hack into a camera and observe the session. In addition to microphones, “these pose some especially high vulnerabilities,” he said. “Clinicians need to pay attention as to whether the cameras they’re using for telecare are on or if they’re covered when not in use. And they should pay attention to security settings on smartphones and ensure microphones are not turned on as the default.”

Dr. Appelbaum said the HIPAA requires that telehealth sessions be conducted on secure systems, so clinicians need to ascertain whether the system they’re using complies with that rule.

“Particularly people who are not part of larger systems and would not usually take on that responsibility, maybe they’re in private practice or a small group, they really need to check on the security level and on HIPAA compliance and not just assume that it is adequately secure,” he said.

Dr. Appelbaum, who is also a past president of the APA and director of the Center for Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University, noted that the major risk for hospitals after a cyberattack is probably not liability to individual patients.

“It’s much more likely that they would face fines from HIPAA if it’s found that they failed to live up to HIPAA requirements,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.